The Navy Department Library

United States Naval Hospital Ships

Preface

The seventeen historical pamphlets published to date in Series II by the Naval Historical Foundation have focused mainly on topics relating to combat, training, and readiness. Not surprisingly, the long history of the Navy provides an enormous and highly colorful panorama of events, personalities and themes in these three areas which are worthy of scholarly study and which relate in a timely way to today's Navy. However, the noncombatant peacetime achievements of the Navy also present a broad field for research and study. In science and technology, diplomacy and exploration, the Navy has charted new courses and brought the full effect of its resources to bear on many problems of a non-combatant nature.

Medicine in particular has been a major field of naval research and activity during times of peace as well as of war. The essays which follow focus on the role of hospital ships in the history of medicine in the Navy, and they emphasize the uniqueness of hospital ships as vessels in which, for a time, command was not held by a line officer. As Commander Schaller points out in the second essay, even though the controversy over line versus medical command of hospital ships reached dramatic proportions at the time of the Great White Fleet Cruise, line command was not officially reinstated until 1923. Court Martial Order 6 of 1921, which is included as the third essay in this pamphlet, presents many of the arguments raised in this controversy over command of hospital ships.

From the early nineteenth century to the present, hospital ships have been an important part of the Navy's response to the medical needs of its own personnel as well as of those with whom the Navy has come in contact. Moreover, the peacetime accomplishments and contributions of hospital ships have earned for them a singular place in the history of naval vessels.

--1--

A History of Hospital Ships

By Milt Riske reprinted from March 1973 issue of Sea Classics

Almost as long as there have been wars fought on or near waters there have been vessels assigned to care for and move casualties.

Ancient history tells how the Romans in their exploits used special boats to remove the sick and wounded. The United States, as did other countries with navies, also found a use for such ships.

During the piracy problems with Tripoli in 1803 and 1804, Commodore Preble designated the captured ketch Intrepid as a ship with hospital duties. The Intrepid is better known, however as the ship that sneaked under the eyes of the enemy and blew up the Philadelphia held captive by the Tripolitans.

The threat of yellow fever in 1859, an epidemic brought on by seamen returning from foreign ports, instigated the first floating hospital in America. The infected sailors were turned away by the marine hospital and it was necessary to find a place to treat them. A New York physician, Dr. William Adison, recently returned from England where he had studied in the floating hospital ship Caledonian, suggested a similar vessel.

When his idea was accepted the port authorities voted funds to purchase the steamer Falcon. The engines were removed, the deck housed over, other necessary facilities installed and various changes made. Fittingly enough the name was changed to the Florence Nightingale, and a number of patients were cared for aboard her.

During the Civil War a captured sidewheel steamer named the Red Rover by its Confederate owner proved to be the U.S. Navy's first hospital ship. This was used originally as living quarters for the men manning the Confederate States' Floating Battery New Orleans. The Red Rover caught a piece of shell when the New Orleans was bombarded by the Western Gunboat Flotilla. The shell pierced her top and slanted through all her decks to the bottom. Although she leaked considerably, the ship was in no danger of sinking. She was captured by the Union gunboat Mound City and almost immediately prepared as a floating hospital for the casualties of the North.

Not long after her capture, the Red Rover became a haven for many injured men and officers of the apprehending gunboat.

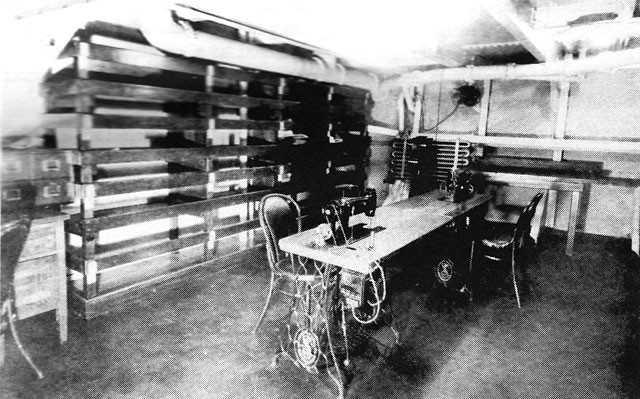

In the summer of 1862 the ship was renovated by the Army Quartermaster Corps to include laundries, bathroom facilities, elevators to upper

--2--

decks, operating rooms, nine waterclosets, separate kitchens for crew and patients, and gauze blinds to keep out smoke and cinders from the convalescents' berth deck.

Enough stores were taken aboard for a crew and 200 patients for three months. This included 300 tons of ice. Commander Captain Alexander M. Pennock reported to his Flag officer, "The boat is supplied with everything necessary for the restoration of health for the disabled seamen."

On June 11, 1862, she received her first patient, a seaman from the gunboat Benton, a victim of cholera.

At this time the Red Rover was really "half Army and half Navy," and it was only after the Illinois Prize Board sold her to the Navy that she could be called a Navy hospital ship. The reorganization and transfer of the Western Flotilla to the Navy helped to solidify this fact. She was commissioned in the Navy the day after Christmas, 1862.

The first vessel designated as a Naval hospital ship had a crew of twelve officers and thirty-five men, exclusive of the thirty surgeons and nurses aboard.

Not all of the nurses aboard were male. Four sisters of the Order of the Holy Cross came aboard that Christmas eve and were joined later by several other sisters and some black female nurses. Unknowingly this small group proved to be the pioneers of a Navy Nurse Corps which would be organized some fifty years later.

Not only was this fledgling hospital ship kept busy with her patients, but she was also pressed into service as a store ship carrying medical supplies, ice and provisions to the ships of the river fleet.

With the establishment of a naval hospital at Memphis, the Red Rover was relieved of some of her duties. As the war between the states drew to a close, so did the need for the Red Rover and she was removed from the service November 17, 1865. Later, stripped of her only gun and iron plate, she was sold at public auction.

Hospital ships are children of necessity, mothered and fathered by wars. The United States War with Spain near the end of the nineteenth century found several liners and cargo ships converted for use as floating hospitals. Two of these remained in naval service after this war, or at least their names were retained.

Two Army hospital ships the Missouri and the Olivette are worthy of mention because of their deeds. The freighter Missouri, a steel ship of 320 feet with a 41 foot beam, was under the British flag. She was a ship of humanitarian service long before she was converted and commissioned for

--3--

hospital usage. On her second voyage in a severe storm she answered a distress signal of the Denmark out of Copenhagen bound for New York with a crew of 170 and 665 passengers, nearly all immigrants to a new land. The Missouri's captain attempted to tow the disabled vessel but found it impossible because of the ice. The Danish ship finally signaled, "Am sinking; take off my people."

With accommodations for only twenty extra people, Captain Murrell of the Missouri jettisoned his cargo to make space for the rescued passengers. First the babies, twenty-two of them, were brought aboard by lifeboat in the raging, icy seas. The little girls were next; one delayed the lifeboat by running back aboard the sinking Denmark to retrieve a loved one - a forgotten rag doll. Then the women; one was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter named Atlanta Missouri Linne before she set foot in her new homeland. The husbands and sons followed; and in the last boat, the officers of the doomed ship.

An artist of the National Academy depicted the deed on canvas titled appropriately, "And Every Soul Was Saved."

As if this heroic deed was not enough, the Missouri continued on her errands of mercy by carrying cargoes of flour and corn to the starving Russians during the famines of 1891 and 1892. Later she rescued the steamship Delaware and towed her to Halifax. She also towed the foundering Bertha to Barry, England.

The Missouri was offered to the Surgeon General of the Army by her owner B. M. Baker of Baltimore for use in the Spanish-American conflict. She was readily accepted. When the British colors were hauled down, the officers who were mostly British, applied for American citizenship and the Stars and Stripes were raised.

Following the example of Mr. Baker, patriotic societies such as the Red Cross, Daughters of the American Revolution, Colonial Dames, and Women's National Relief Association, donated such items as refrigeration plants, steam laundries, motor launches, etc. All these, plus the stocking of the library with 10,000 books and magazines by Wall Street capitalists, made the Missouri even more effective as a floating hospital. Although without the public glamor of her earlier benevolences, the Missouri continued her life saving efforts as a hospital ship during our war with Spain.

The Olivette was also a transformed steamer. It served with early landings in Cuba. At the end of the skirmish she received Admiral Cervera, Commandant of the Spanish fleet with many of his officers and men. Some of them were severely wounded and were taken from his flagship, the Maria Theresa.

--4--

Realizing the success of the Red Rover as a floating hospital, the U.S. Navy made more extensive use of hospital ships in this war with Spain.

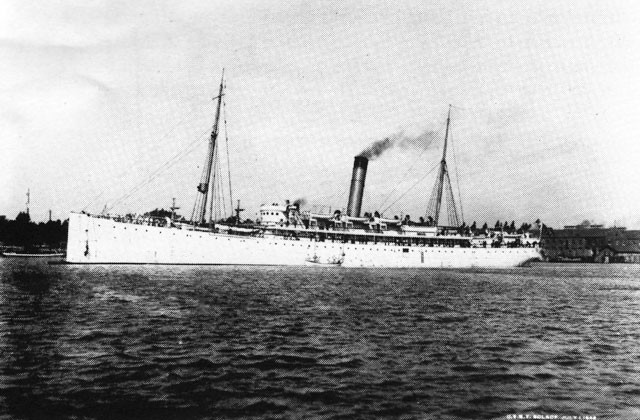

The Solace was purchased from Cromwell Steam Ship Lines where she had been in service to the West Indies as the S.S. Creole. Through accelerated wartime effort of the shipyards and a donation from the Red Cross committee, the ship was converted for hospital duties in 16 days. After her Navy war service she was pressed into Army transport work, sailing between the West Coast and the Philippines.

In 1909 a great amount of super-structure was added to carry antenna. With only a 44 foot beam and 377 foot length, she rolled excessively. Sometime between 1912 and 1914 her height was lowered and, it was rumored, some 200 Civil War cannon were embedded in concrete to counteract the roll. This story, repeated in wardroom and forecastle throughout the fleet made a hospital ship "the most heavily gunned in the Navy."

After service in World War I, the Solace was decommissioned.

To heighten the confusion over names of hospital ships, there have been five ships named "Relief" and but two of them have been used as seagoing hospitals. Of the other three, one was a stores ship, one a wooden patrol boat, and the other a salvage tugboat. It is only with the second and fifth Reliefs that we are concerned.

--5--

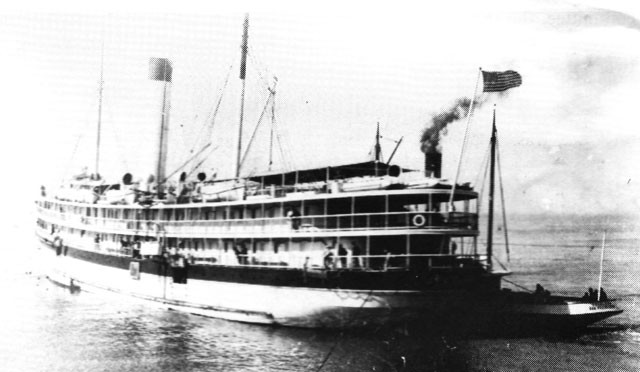

The second Relief was originally a passenger cargo steamer named the John Engles and was purchased by the Army for hospital purposes in 1898. She served in the Pacific and returned the heroic casualties of the Philippine fighting to San Francisco. She made several stops, including Honolulu, to show off her patients to a grateful and cheering public.

After the war she was transferred to the Navy and at Mare Island was refitted as a Naval Hospital ship. Her commissioning was delayed in an intra-service squabble over the command, whether a line or medical officer would be in charge. Pointing out that with a combatant line officer in charge, the ship would not be subject to immunity from enemy attack, the Navy Department put the ship in the command of the medical department. A sailing master and a civilian crew were in charge of sailing the vessel.

This rule was altered in 1916 when a Congressional Act allowed deck and engineering duties to be in the hands of the Naval Reserve Force. The ship remained in the command of a medical officer.

In 1921 another change of rules came about when a reserve deck officer refused to sign a noon position, claiming it was not in his realm of duty to do so when commanded by a medical officer. Regulations were changed giving the position of command back to the line officer.

The Relief became part of Theodore Roosevelt's "Great White Fleet" of sixteen battleships. She met the fleet on its diplomatic around-the-world

--6--

cruise in Magdelena Bay, Mexico, and relieved the ships of their 152 ailing accumulated since the departure from Hampton Roads.

After debarking her patients in San Francisco, she followed the Fleet up the West Coast where she helped to stem an invasion of scarlet fever aboard the USS Nebraska.

Again in Honolulu she received diptheria patients from the same battleship. All in all, the medical crew on the Relief received some fine postgraduate training as she followed the fleet to Australia.

She was detached from the Fleet in the Philippines, but on return to the States she was disabled by a Pacific typhoon and forced to return to the islands. Found unseaworthy, she became a floating dispensary at Alongapo and her name was changed to the Repose. Relief was then available as a name for another hospital ship. The end of the Repose came in May, 1919.

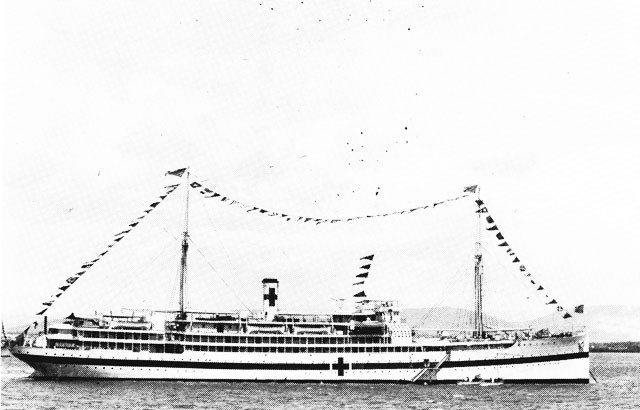

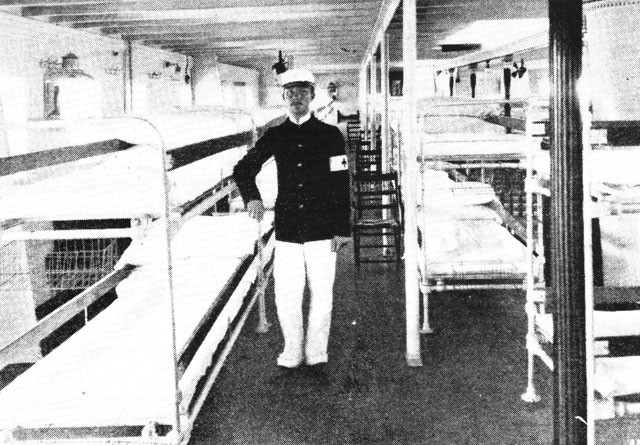

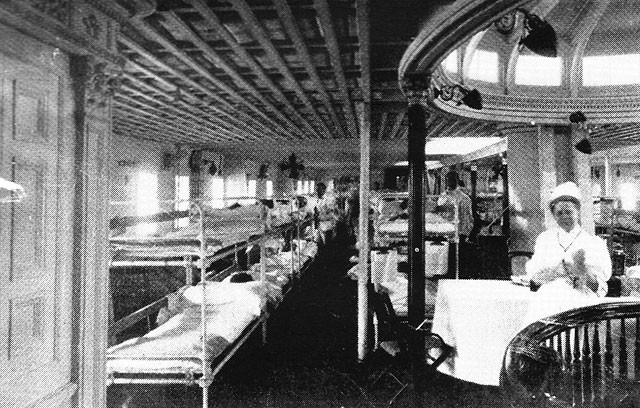

The next Relief , assigned and built strictly as a hospital ship, was the most modern and best equipped ship of this kind in the world. She had a complement of 44 officers and 331 enlisted corpsmen. She could handle 500 patients and contained all of the conveniences of a shore hospital including specialists for any branch of medical service. Serving the fleet in both oceans, she was in Norfolk, Va., when the United States was bombed into World War II.

--7--

At the time of this bombing, the second Solace (AH-5) was the only hospital ship operating in the Pacific. Originally the S.S. Iroquois, she was converted in 1927 for hospital service. She was anchored at Pearl Harbor when at 0800, this bright and calm Sunday morning was shattered by Japanese bombers. By 0825 the first patients began to arrive and this hospital ship was virtually at war.

Until she was joined by the Relief from her North Atlantic duties, by the Comfort and also the Tranquility, the Solace, known as the "Great White Ship," carried on alone doing an efficient and noteworthy job servicing the fleet at such bloody places as the Coral Sea, Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima.

The last major operation at Okinawa brought into enemy action the suicidal Kamikaze attacks. Even the well-lighted and weapon-powerless hospital ships were not immune to the treacherous divers. The Comfort was attacked and damaged forcing the Solace and other hospital ships to blackout and do their rescue work in perilous waters.

--8--

Hospitals afloat, as medical technology ashore, have come a long way. In 1908 the first Navy Nurse Corps was formed, although it was not until 1918 that they were permitted to fulfill their duties aboard ships and finally on troop transports. It was 1920 before nurses served aboard the Relief·

Many of the old tars and salts, so long able to look after themselves in their male world of the sea, opposed such radical innovations as women aboard ship. Replacement of the loblally boys - so called because of the thick gruel called loblolly which was served to the sick and wounded by boys on ship - with nurses and well trained enlisted corpsmen gained acceptance slowly. The men in the fleet room grew to have great faith in the men and women of the hospital ships and new methods were accepted as a part of progress just as disinfectants replaced vinegar as a germ killer and rum and laudnum were replaced by anesthetics.

With the advent of mass air transport for troops, how useful will hospital ships be in the future? These ships with benign and peaceful names were used in the Korean conflict. The Repose and the Sanctuary have been maintained in the Vietnamese waters with a useful purpose. The ships have been modernized with launching pads for helicopter transport and, of course, contain all of the latest medical facilities of a shore-based hospital. A far cry from the old Red Rover is the modern hospital service vessel, yet with the same dedication to humanity.

--9--

Naval Command at Sea

The Story of the Hospital Ship Relief #1

By WALTER F. SCHALLER, M.D., Commander, USNR (Ret.)

On November 9, 1965, I was one of a group invited to inspect the Hospital Ship Repose, at dock in the San Francisco Navy Yard, which, after years of inactivity with the "mothball fleet" in Suisun Bay, California, following World War Two, had recently been modernized and recommissioned for service in Viet Nam. As I toured this imposing ship, so well supplied with the latest medical and surgical equipment and staffed by the Navy's most experienced officers, I could not help comparing her with the Hospital Ship Relief #1, on which I served as Assistant Surgeon when she joined the Great White Fleet of Theodore Roosevelt in Pacific waters over a half-century before. Both ships had experienced long periods of inactivity: the Repose because she was not needed in a peace-time Navy, but the Relief because of the sharp controversy over the question of command, not only of medical personnel but of the ship itself, which arose between the two large navy departments - Navigation and Medical Staff, resulting in a five year delay in commissioning after the Navy acquired her from the War Department following the Spanish American War. President Roosevelt ultimately decided in favor of Medical Staff command.

The history of the Hospital Ship Relief has been a subject of considerable research on my part. After World War Two, long after I had left the regular naval service to enter the Naval Reserve, my duties as Area Medical Consultant with the Veterans Administration took me frequently to Washington. Here I often saw my old shipmates, Doctors Strine and Trible and Captain Walter Sharp, all of whom had retired and lived in the Capitol. They reminisced in detail about the career of the Relief after I was detached, relating the harrowing events of her last voyage in which she narrowly escaped disaster. I felt strongly that the story of this cruise should be recorded, and repeatedly urged my friends to do so. My suggestion, however, met with a marked reluctance and the excuse of not wishing to "revive old animosities."

Although I did not complete the cruise I was quite familiar with the ship and its complements, and had at my disposal the ship's Log, the diary of Doctor Strine (made available to me after his death), and I had numerous conversations with Captain Sharp, who is the only surviving officer of the ship, other than myself. Admiral F. Kent Loomis, Assistant Director of Naval History, encouraged me in the project and rendered valuable assistance in providing me with official data.

I therefore consented to undertake the task. Gradually, as my investigation proceeded, it became apparent that the controversy over command,

--10--

far from being settled, had persisted until 1923, when line command was finally reinstated.

The line command of naval vessels had been unquestioned, until it was ruled under the Geneva Convention that hospital ships were to be classed as noncombatants. The question then arose whether the command of such a ship by an officer trained in warfare might not jeopardize the noncombatant status. This viewpoint, forcibly advanced by Surgeon General P. M. Rixey, influenced Theodore Roosevelt to appoint a naval surgeon to the command of the Relief. All final decisions were, therefore, of necessity to be made by medical officers, untrained in navigation, engineering, and sea-faring in general; navigation on the Relief was directed by a sailingmaster, F. N. LeCain, of the Naval Auxiliary, and other important departments, such as engineering, were likewise under direction of Auxiliary officers. When, in 1907, the order was given to rehabilitate the Relief for service with the Great White Fleet in Pacific Waters under command of Surgeon Charles Stokes, loud protests were heard from the line, which regarded the order as an "outrage." It was stated that Admiral Brownson, Chief of Navigation, resigned his post rather than issue the order.

The Relief was built in 1896 for use as a passenger and cargo ship along the New England Coast. She served as a "floating ambulance" with the Army in the Spanish American War and was acquired by the Navy in 1902. However, she remained inactive at Mare Island Navy Yard until 1908, after the question of command was settled.

The need for a modern hospital ship had long been stressed by the Surgeon General of the Navy, but Congress repeatedly refused the necessary appropriations. Faced with the necessity to provide for the medical requirements of the Navy, the Surgeon General apparently was forced to accept a compromise between no hospital ship and one especially designed and constructed for service at sea.

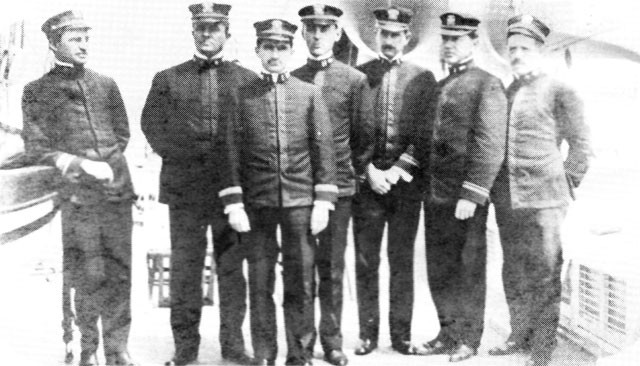

The Relief was a schooner-rigged, single screw steam with a wooden superstructure and powerful triple expansion engine. She had accommodations for 195 patients, for whom bunks were provided in wards. Aft on the hurricane deck a 30 cot infectious ward was constructed, mosquito and fly-proof. On the lower deck were two padded cells for "insane" patients. The medical officer in command and his staff were specially selected; the class just graduated from the Hospital Corps Training School in Washington, D.C., was transferred to the ship as a body. In command was Charles F. Stokes, inventor of the Stokes stretcher and later Surgeon General of the Navy. The Executive Officer was Surgeon Arthur Dunbar, a strict disciplinarian, whose fire drills, unexpected as they were thorough, probably saved the ship from destruction on her final trip. Surgeons Raymond Spear and Howard F. Strine, and Assistant Surgeon J. O. Downey

--11--

formed the medical staff when I joined the ship; Dr. George Trible joined the ship after I was detached. The only other naval officer on board was Walter D. Sharp, Assistant Paymaster.

My naval career had begun some two years prior to joining the Relief; in fact, my first orders were dated April 18, 1906, the day of the San Francisco earthquake and fire. Following initial duty at Mare Island, I was ordered to the Naval Medical School in Washington, D. C., for a six months course in the special fields of naval medicine- regulations, drills, communications, and especially hygiene and communicable diseases - but no instruction was given in general seafaring and none whatever in navigation, engineering or ship command.

For several months prior to joining the Relief I had had duty on board the Cruiser Pennsylvania at Magdalena Bay, Mexico, and learned about the bay through various off-duty side-trips fishing, sailing and hunting. So it was to familiar surroundings that I sailed on the Relief a few days after joining her, as she was ordered to Magdalena Bay on March 24 to join the Great White Fleet for transfer of hospital patients.

The Relief approached Magdalena Bay on the night of March 27. We had no chart of the channel aboard; the Sailing Master had never before entered the harbor. Since I was apparently the only officer on the ship who had been in these waters, I was called to the bridge and questioned as to whether I knew of any reefs or shoals. As I knew of none, it

--12--

was decided to proceed cautiously, and thus we anchored with the Fleet. Our captain, however, had neglected to signal our arrival and request permission to anchor, and when the presence of our high-riding excursion-like vessel was disclosed at sun-up, reproof from the flagship was immediately forthcoming.

The Relief spent a busy week in port transferring patients from the Fleet to be taken to Mare Island Hospital. The Fleet Commander, Admiral Robley Evans, suffering from a severe attack of gout, was sent north for hospitalization on board the ceremonial yacht, the Yankton. Doctors Spear and Strine, whom I assisted in surgery, spent long hours in the operating room. We then headed north. The Relief proved her reputation as a notorious "roller," making for an uncomfortable trip for all. An entry in Doctor Strine's diary notes: "Motion . . . more motion . . . almost everyone sick . . . Schaller and Downey down and out."

Prior to my assignment to the Relief I had planned to resign from the Navy in order to pursue graduate studies abroad. My resignation was accepted on June 1, 1908; it might be said that I was shaken into the Navy by the San Francisco earthquake and rolled out by the Relief.

The triumphal entry into San Francisco Bay on May 6, 1908, of the Great White Fleet, marking roughly the half way point of this legendary

--13--

voyage, was an event still remembered vividly by those who witnessed it. Sixty special trains carried visitors to San Francisco; a grand ball held at the Fairmont Hotel lasted 24 hours. Before and after this celebrated event visits were made by a detachment of the Fleet to various harbors along the coast, and the hospitality shown officers and men was unsurpassed. The Relief went as far north as Puget Sound, and members of the medical staff, including myself, were entertained in Seattle at a banquet at the Rainier Club, where I recall Surgeon Stokes responded in a particularly happy vein to the address of welcome.

The Relief left for Hawaii in advance of the Fleet. On this leg of the voyage the refrigeration broke down, with consequent spoilage of frozen meat stores. This was but the first of a series of mishaps during the voyage through the South Seas and Australia, which eventuated in the separation of the Relief from the Fleet at Sydney. It was common gossip that the Relief had to be "nursed" by the Fleet. Of interest was meeting the Snark in Pago Pago, with her owner Jack London and Mrs. London aboard. Fate decreed that neither of these vessels was destined to return to her home port of San Francisco.

Particularly rough weather was encountered on the trip from Samoa to Auckland. A roll of 55 degrees was reported; patients were with difficulty kept in their bunks, much glassware was broken, and at one time only two boilers were operating. At Sydney, coaling difficulties arose, due to labor union disputes. This problem was quickly solved when Lt. Commander C. B. McVey, who commanded the escort ship Yankton, rounded up 75 stragglers from the Fleet, who had celebrated a bit too long in Sydney and missed the departure of their ships for Melbourne. He put them to the task of coaling the Relief; then, without benefit of showers, bundled them on board a passenger vessel to rejoin their ships.

It was decided by the head command to detach the Relief from the Fleet in Sydney, and send her to Manila for repairs. The Yankton acted as her escort and a pilot was provided through the Polynesian waters. This was the second of two occasions in which the Commander-in-Chief's yacht rendered signal service during the cruise; the first, as recorded at Magdalena Bay in transporting the Fleet commander, Admiral Evans, to a base hospital, and this other when the hospital ship itself, so to speak, was on the sick list and was also rendered assistance.

In Manila a survey board decided that the Relief should return to the Pacific Coast via Guam for overhaul; the separation at Sydney had become a divorce. Sailing date was set at November 16, although it was typhoon season and the Fleet had encountered a severe storm on the way to Japan. She was to sail without escort; nor was she equipped with wireless.

--14--

Typhoon signals were up and the barometer falling when the Relief left Manila on the long trip to the Pacific Coast. Permission to delay sailing was signalled Captain Stokes, who, however, was insistent that departure not be delayed. The weather became increasingly threatening, and on reaching San Bernardino Straits Sailing Master LeCain advised that the ship "lay to" in the lee of the islands before proceeding to the open Sea. This advice was overruled. (According to the diary of Doctor Strine, Captain Stokes said, "We'll show them that the Medical Corps is not afraid of a typhoone. Out we go!")

The account of the final adventure of the Relief, which challenges the imagination, was compiled from various sources. The most graphic description was found in Doctor Strine's diary; the ship's Log is notably lacking in particulars concerned with the momentous decision to proceed.

On the night of November 18 the Relief encountered a storm of such intensity that the wind velocity was recorded at 11, the barometer fell to 28.1, a near record low. The engine and dynamos were disabled. Fire broke out in seven different places during the night. There was extensive damage to the ship's superstructure. As mute evidence of the severity of the storm, I still possess two volumes of lectures of the Naval Medical School Session of 1906-7, warped and water-stained by the inundation of the officers' quarters on the upper deck; these I had lent to Doctor Downey.

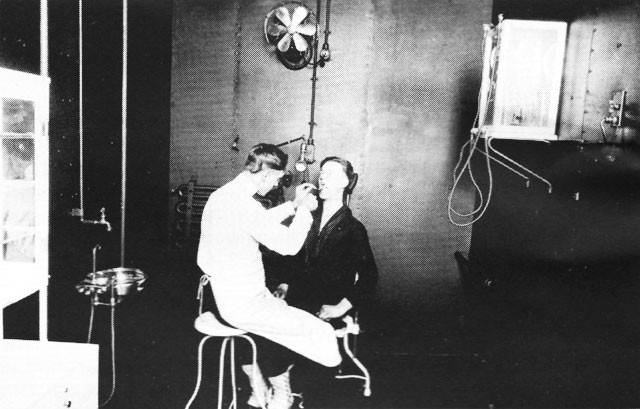

When the storm abated, the ship had been driven far off the beaten track. Sails were set and a sheet anchor was put out to keep her "head to the sea". Attempts to repair the engine were unavailing until November 22, when the difficulty was solved by Horace E. Perlie, a hospital corpsman. He had received dental training and served as the ship's dentist, since at that time there was no regular dental corps in the Navy. He identified a broken eccentric strap as the cause of the breakdown, worked continuously for 24 hours to improvise a new one, which he fashioned by hammering out three crowbars. Her engine restored, the ship limped back to Manila at 10 knots, arriving approximately on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, after an absence of ten days filled with dread and anxiety.

That the officers and men of the Relief were a dauntless crew, who survived by courage and great good fortune the two great hazards of the sea-storm and fire-is attested by their rendering a light opera, "The Land of Utopia," on New Year's Day, 1909, only five weeks after their return. The role of the leading lady was played by Horace E. Perlie!

The career of the Relief as a cruising hospital ship had ended. A board of inspection pronounced her unseaworthy, and she filled out her days as a stationary hospital ship anchored at Olongapo, P.I., her name fittingly changed to Repose.

--15--

Changes in the construction and outfitting of hospital ships since the days of the Relief have been as vast as the changes in medicine itself. Today no expense is spared to provide our servicemen with first-class medical care and equipment. The experience of the Relief suggests that one of the most important changes of all has been the reversion of over-all command of hospital ships to the trained, responsible and experienced officers of the line. It is improbable that a professional line commander would have so disregarded the safety of ship and crew as to sail into the teeth of a storm, alone, without wireless, and against all advice.

Court Martial Order #6, 1921

Following is the report of the Court Martial involving the question of command of hospital ships by medical officers.

DISOBEYING THE LAWFUL ORDER OF HIS SUPERIOR OFFICER. What constitutes.

COMMAND BY STAFF CORPS IN LINE .

HOSPITAL SHIPS. Command of.

1. An officer of the United States Naval Reserve Force was tried by a general court-martial convened by the commander in chief, United States Pacific Fleet, on the following charge and specification:

CHARGE.-Disobeying the lawful order of his superior officer.

SPECIFICATION. - In that * * *, United States Naval Reserve Force, serving on board the U.S.S. * * *, having, on or about March 13, 1921, on board said ship, been ordered by Commander * * * (M. C.), U.S. Navy, the commanding officer of the said ship, to sign Form N. Nav. 143 for the noon position of said ship, did then and there refuse to obey and did willfully disobey said lawful order, the United States then being in a state of war.

The accused was found guilty as charged and sentenced to be dismissed from the United States naval service. The convening authority, commander in chief, Pacific Fleet, approved the proceedings, findings, and sentence and referred the record to the Secretary of the Navy for transmission to the President, in accordance with article 53 of the Articles for the Government of the Navy.

2. Disobedience of lawful orders constitutes one of the most serious offenses known to military law, and the sentence adjusted by the court in this case is clearly commensurate with the offense alleged if, in fact, the accused is legally guilty thereof. From a very careful review of the record, this case presents many unusual conditions and as such necessitates very careful consideration. From the facts disclosed in the record two salient and determining points are involved: First, assuming that Commander

--16--

* * * as commanding officer could legally issue an order to the accused, was the accused's refusal to obey the order to sign Form N. Nav. 143 for the noon position of the ship a disobedience of a lawful order such as would make it a military offense and the accused punishable therefor; second, did Commander * * *, an officer in the Medical Corps of the United States Navy and commanding officer of the U.S.S. * * *, have the lawful authority to issue such an order to * * *, an officer of the line in the United States Naval Reserve Force.

3. In taking up the first point involved and as set forth, supra, it is important to know what constitutes a lawful order and also when orders as such become operative; that is, when they acquire such binding force as to confer upon a failure in respect to obedience the character of a military offense. The presumptions of regularity and good faith which attend public officers in the performance of their duties apply to the orders of a superior with precisely the same force as to his other official acts, and, therefore, the general rule is that an order legal on its face is presumed to be legal. The accused may in his defense, however, rebut that presumption, failing in which he can properly be found guilty.

4. A lawful order may be defined as a command issued by a military superior to a person under his command requiring an act to be done which is permitted, sanctioned, or justified by the law of the land. (Davis Military Law, p. 381.) To justify, from a military point of view, a military inferior in disobeying the order of a superior, the order must be one requiring something to be done which is palpably a breach of law and a crime or an injury to a third person, or something of a serious character (not involving important consequences only) which, if done, would not be susceptible of being righted. An order requiring the performance of a military duty cannot be disobeyed with impunity unless it has one of these characters. (Dig. J. A. G. Army, 27, par. 7, Davis Military Law, p. 381.) Of the characters enumerated the case at bar falls within the class last named. Examining the specification carefully with due regard to the import of the offense alleged, together with the evidence adduced in reference thereto, we find that the accused was attached to the U.S.S. * * *, and assigned by the medical officer in command to duty on board as "senior deck officer." Neither this title nor the duties thereof are prescribed in Navy Regulations, 1913 or 1920. He had had 23 years' active sea service, about 12 years of which was as deck officer and master of various steamers, passenger and cargo and oil tankers, including about three and one-half years in the Naval Reserve Force. Commander * * *, a medical officer, ordered the accused to sign Form N. Nav. 143 for the noon position of the ship. It should be borne in mind that this form was at the time of the issuance of the order filled out with a noon position and signed by the officer who had by calculations determined upon the report given.

--17--

5. The U.S.S. * * * was making passage from Mare Island, Calif., to San Pedro, Calif., at the time the accused refused to sign the noon report. Commander * * *, the commanding officer, testified (p. 15, Record, 4.AA): "At 12.20, the time I went to see Mr. * * *, it was very foggy and thick." The lookouts on the ship had been doubled. (Rec., p. 38, A.22.) All had been directed to particularly keep their ears open and a steamer's whistle was heard on the starboard bow. Shortly after, at 12.26 p.m., the Point Arguella fog siren was picked up on the port bow. (Rec., p. 40, A7.) It was estimated that the sound of the fog siren was abeam at 12.39 p.m. A sounding showed 39 fathoms, and when it was considered that Point Arguella was abeam the course was changed from south 48 east to south 65 east per standard compass. From the foregoing it will be seen that at the time of the refusal of the accused to sign the report the ship was on soundings, in a heavy fog, a steamer not visible on the starboard bow, and a sound signal on shore, the location of which determined a change of course. The circumstances surrounding the accused's refusal was that Lieut. * * *, the line officer on the ship, designated as the navigator, was directed by the accused that "as the weather is now thick again, I could not enter the chart room to figure out the noon position." (Rec., p. 40, A6.) The accused had roughly marked the position on the chart based upon a speed that had been reduced; he instructed Lieut. * * * to allow 2 miles back of that position and to fill out the noon report, sign it, and turn it in to the commanding officer, who had previously the night

--18--

before, under similar weather conditions, authorized such procedure. The commanding officer testified: "I returned this position report by the orderly to Lieut. Commander * * * and requested that he sign it. The orderly returned, stating that Mr. * * * would not sign the report at that time. I again returned the position report by the orderly, directing Mr. * * * to sign it, or state in writing, his objections to me, the reasons. The orderly returned to my cabin and stated that Mr. * * * would sign the position report after the weather cleared up. I then personally took the position report up to the first deck and directed Mr. * * * to sign it. He stated he could not sign it then. I then asked him if he refused to sign it. He stated he did."

6. In determining the propriety and justification of the accused's refusal it is pertinent to consider other evidence as brought out by the testimony of the commanding officer. When asked, "47Q. Was the ship on sounding at the time," he testified: "A. According to the log it was not." The counsel for the accused then, in comment to the court, stated that Commander * * * as commanding officer was required to be on the bridge and take part in heavy weather when on sounding or in other imminent danger; that the witness must know the answer to the question of his own knowledge and not refer to the log. "We have the log here and he can use it." The court then stated: "Does the witness desire to make any other answer to that question." "A. I do not." The witness, when asked how far the ship was from land, stated: "Not to my knowledge." (Rec., p. 16, q. 47.) He further testified: "I have always considered that everything pertaining to the navigation of the ship was under the charge of Lieut. Commander * * *." (Rec., p. 16, A80.) Also, "52Q. If the scope of your authority as commanding officer was similar to that of commanding officers of other vessels of the Navy, of which navigation of the ship was one, your duty would be on the bridge of the ship in fog or heavy weather? A. As commanding officer of a battleship - yes; of a hospital ship - no." Also, "55A. * * * I have never taken any actual part in the navigation of the ship."

7. That the very reason which actuated the commanding officer to order the accused to sign the noon report were the same reasons which governed the accused in refusing to sign the report is indicated by further testimony given by the commanding officer. "Q. 24. If the accused had signed that paper at the time, would you consider it proper for him to sign it without further investigation?" "A. My confidence in Mr. * * * is such that if he had signed that I knew it would be all right." "25. Q. Now, is it not a fact that the policy of the whole Navy, the policy which obtains in civil life, that no one should sign a paper without first satisfying himself or themselves that the facts mentioned therein are correct; is not that the policy which obtains in the service, Captain?" "A. Anything which an officer

--19--

signs he is responsible for." (Rec., p. 30.) It is interesting to note that Commander * * * testified that he did not report the noon position on March 13, 1921, to the commander in chief or to the commander of the train, due to the fact that Lieut. Commander * * * refused to sign the position report. "I had received an order from the chief of staff to report my position, and I consider it my duty to get the best position possible and the best authority to make my noon report." (P. 31, Rec., A. 33.) In fact, the commanding officer disobeyed the lawful order of his superior officer and ostensibly justified his act upon the lack of sufficient and reliable information upon which to base such a report.

8. One of the governing causes that the commanding officer gave as his reason for insisting that the accused sign the noon report was that he had issued in writing an order to the accused making it his duty to "fill out N. Nav. Form 143 in every respect and submit the same to commanding officer over your signature at 8 a.m., 12 noon, and 8 p.m. Under remarks you shall state distance gone, distance to go, and probable date and time of arrival." However, in determining the guilt of the accused, reference must be had to the charge and specification as laid. If the accused in this case had been charged with neglect of duty and the specification alleged that he failed to fill out the noon report on March 13, 1921, as it was his duty to do, then that would have presented a different situation and the pertinence of the remarks hereinbefore stated would have a different relative bearing.

9. In deciding the culpability of the accused upon the first point set forth herein recourse can only be had to the allegations as laid, to wit, the accused's refusal to sign N. Nav 143, which had already been filled out by another. "Where an officer respectfully declined to comply with the directions of his superior to sign the certificate to a report of target firing on the ground that the facts set forth in such certificate were not within his knowledge, he having been stationed at the butt, where he was not in a position to be informed as to such facts, held that he was not amenable to a charge of disobedience of orders under this article." (Dig. J. A. G. Army, 30, par. 16. See also ibid., 29, pars. 12, 14, and 15; also Davis Mil. Law, p. 381.)

10. A junior cannot shed himself from all responsibility for an act committed by himself under the protection of an order issued to him by his superior if the order itself was illegal. "Soldiers might reasonably think that their officer had good grounds for ordering them to fire into a disorderly crowd which to them might not appear to be at the moment engaged in acts of dangerous violence, but soldiers could hardly suppose that their officer could have any good grounds for ordering them to fire a volley down a crowded street when no disturbance of any kind was either in progress or apprehended. The doctrine that a soldier is bound under all circumstances

--20--

whatsoever to obey his superior officer would be fatal to military discipline itself, for it would justify the private in shooting the colonel by the orders of the captain, or in deserting to the enemy on the field of battle on the order of his immediate superior.' (2 Willoughby Const., 1195, quoting Stephen's Hist. Cr. L. Eng., 205.)

11. From the evidence adduced there was on board the hospital ship at the time of the alleged offense a number of sick, whose rescue in case of disaster, according to the testimony of Commander * * * was problematical. The commanding officer did not, in accordance with his own testimony, in any way exercise any supervision over the safe navigation of the ship, but placed the responsibility therefor upon the accused, who was merely ordered to the ship for duty under the commanding officer. This presents an anomalous situation in maritime custom, but the accused realized and knew this to be a fact, and testified that when he read the order to sign the report he considered it a very critical time. With the ship steaming in a thick fog, on sounding and within close proximity to shore, with the sound of an unseen steamer on the starboard bow, with the sound of a shore station on the port bow, on a course that was to be changed at the proper and proximate time, in a lane traversed by seagoing vessels, the meeting of which was more probable in thick weather at this place, can it be assumed that the accused, upon whose shoulders the responsibility for safeguarding the ship and lives on board rested, would have been warranted and absolved from blame if a disaster had resulted as a result of his compliance

--21--

with the order of the commanding officer, who actually did not assume any of these responsibilities, nor was familiar with the conditions that existed, taken the report and checked all the data required thereon, thereby taking himself away from all possibility of exercising active control of the navigation of the ship? There seems to be no other reasonable or logical conclusion but that he would not have been so justified, and his action, if so executed, would have fallen within the classification of something of a serious character, which if done would not be susceptible of being righted. On the first of the points hereinbefore referred to I am therefore of the opinion that under all the circumstances of the case the actions of the accused do not constitute the military offense of disobedience of the lawful order of his superior officer.

12. Taking up the second of the points hereinbefore referred to, it must be noted that the accused was not on board the hospital ship U.S.S. * * * as a patient, but, on the contrary, he was an officer attached to the U.S.S. * * * by order signed by the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, which directed him to report to the commanding officer of that ship for such duty as might be assigned to him on board. Therefore the question resolves itself into whether an officer of the line of the Navy, ordered to duty on board a hospital ship commanded by a medical officer of the Navy, is subject to his military command for the performance of line duties or such other duties as his commanding officer may direct. The accused in this case is an officer in the line of the United States Naval Reserve Force, and as such he is on the same basis as an officer in the line of the Regular Navy, and therefore no differentiation need be made between the two in the discussion of the case at bar. The act of August 29, 1916, provides:

"Enrolled members of the Naval Reserve Force shall be subject to the laws, regulations, and orders for the Government of the Regular Navy only during such time as they may by law be required to serve in the Navy, in accordance with their obligations, and when on active service at their own request, as herein provided, and when employed in authorized travel to and from such active service in the Navy." (38 Stat., 588.)

Officers of the United States Navy shall be known as officers of the line and officers of the staff. (Art. 148, Navy Reg., 1920.) Officers of the line exercise military command. (Art. 148, Navy Reg., 1920.) The Navy Regulations are silent insofar as a definition of staff officers is concerned, although it designates the officers of the staff as follows: Medical officers, dental officers, supply officers, chaplains, professors of mathematics, naval constructors, and civil engineers. (Art. 151, Navy Reg., 1920.)

13. It is obvious that every military establishment, whether Army or Navy, must have connected with it certain organizations of business or scientific men whose services, although auxiliary to the combatant force of

--22--

such establishment, are yet necessary to its efficiency. These constitute the staff corps as distinguished from the line. It is also necessary that the officers of such corps, being gentlemen who render important and valuable services, should be brought into such relations with the officers of the line that their dignity shall be preserved and the proper order of a military establishment maintained. While, therefore, rank is primarily established with those who are entitled to command with a view to determining the order in which they are to command, it is necessary to give to the grades created in other corps a rank which shall either be the same with the rank of the officer of the line or which by relation to the rank of the officer of the line shall entitle those holding it to such attention and respect as is accorded to officers of the line of the rank to which it relates or is assimilated. Such rank, whether it be absolute or relative rank, may, of course, be always subject to such exceptions as the legislative power may deem proper. In January, 1871, a bill was passed by the House of Representatives which gave to each staff officer definite or absolute rank. This bill was the subject of much discussion, and in the Senate it was amended and finally passed by both Houses of Congress in the form which gave to the officers of the staff relative rank, the phrase used in regard to such officers being-e.g., "13 pay inspectors, who shall have the relative rank of commander" * * *. It is impossible to conceive why this change was made if Congress, when it finally passed the bill, did not suppose that the "relative" rank of commander was something different from the rank or grade of

--23--

commander. While, undoubtedly, Congress might provide that he should have the absolute rank of commander and might annex to it appropriate conditions, considering the duties expected to be performed by him, such as that he should not exercise "military command," it is apparent that in inserting the word "relative" Congress has made the provision that it deemed necessary for the respect which was undoubtedly to be accorded to him. (16 Op. Atty. Gen., 414.) That Congress by giving relative rank to staff officers did not intend thereby to extend to them military command, additionally provide that "the relative rank given by the provisions of this chapter to officers of the Medical, Pay, and Engineering Corps shall confer no authority to exercise military command." (Sec. 1488, Rev. Stat.)

14. Section 1488, R. S., quoted, supra, was amended by the following provisions in section 7 of the Navy personnel act of March 3, 1899 (30 Stat., 1006):

"All sections of the Revised Statutes which, in defining the rank of officers or positions in the Navy, contain the words 'the relative rank of' are hereby amended so as to read 'the rank of,' but officers whose rank is so defined shall not be entitled in virtue of their rank to command in the line or in other staff corps."

Insofar as the law at present stands as regards medical officers, the above-quoted act of March 3, 1899, is governing and therefore restricts them from exercising command in the line or other staff corps unless it is repugnant in its application to the act of March 3, 1901 (31 Stat., 1153), wherein it is

provided: "That the President of the United States be, and he is hereby, authorized to establish and from time to time to modify, as the needs of the service may require, a classification of the vessels of the Navy, and to formulate appropriate rules governing assignments to command of vessels and squadrons."

Article 668, Navy Regulations, 1920, reads:

"A hospital ship, being assimilated to a naval hospital on shore, shall be commanded by a naval medical officer not below the grade of lieutenant commander, such commanding officer being detailed by the Navy Department."

15. Thus in enacting the above law did Congress intend to raise all restrictions of previous law as regards the duties that could be assigned to officers of the staff corps by providing that the President could "formulate appropriate rules governing assignments to command of vessels and squadrons." If this was the intent of Congress, then under this authority any officer of any staff corps could be assigned in command of a vessel or

--24--

squadron so that it would apply not only to a medical officer, but also to a chaplain, professor of mathematics, etc. Therefore, it necessarily follows, insofar as the law is concerned, that a chaplain could legally be assigned to command a ship or squadron.

16. In arriving at the meaning of a statute where the proper construction is doubtful, it is always proper to consider the history of the statute and the different steps taken in the enactment of the law as disclosed by the legislative records; also to look into the conditions surrounding the subject matter of the legislation at the time the act was passed and the situation as it existed and as it was pressed upon the attention of Congress. (Clark's case, 37 Ct. Cl., 60; U.S. v. Smith, 197, U.S. 386; Holy Trinity Church v. U.S., 143 U.S., 457.)

Section 1539, Revised Statutes, provided that--

"The vessels of the Navy of the United States shall be divided into four classes, and shall be commanded as nearly as may be as follows: First rates, by commodores; second rates, by captains; third rates, by commanders; fourth rates by lieutenant commanders."

Section 1530, Revised Statutes, provided that--

"Steamships of forty guns or more shall be classed as first rates, those of twenty guns and under forty, as second rates, and all those of less than twenty guns as third rates."

17. The foregoing laws were passed by Congress, 16 July, 1862. It will be noted that in the designation of command for the classification of ships, the titles, commodore, captain, etc., were used. These titles were applied only to officers of the line, staff officers' titles being then designated and distinguished in the law by appropriate titles commensurate with the duties performed, such as chaplains, pay directors, medical directors, etc., Congress clearly indicating thereby that line officers only should command rated vessels of the Navy. In the preparation of the naval appropriation bill which, finally approved, became the act of 3 March, 1901, the following provisions were inserted:

"That sections 1529 and 1530 of chapter 6, Table XV, of the Revised Statutes of the United States be amended so as to read as follows:

"'SEC. 1529. Vessels of the Navy of the United States, except torpedo boats and other special vessels, shall be divided into four classes, and shall be commanded as nearly as may be as follows: First and second rates, by captains; second and third rates by commanders; fourth rates, by lieutenant commanders and lieutenants; torpedo boats and other unclassified vessels, by officers below the grade of lieutenant commander.

--25--

"'SEC. 1530. Vessels of 5,000 tons displacement or more shall be classed as first rates; those of 3,000 tons or more and below 5,000 tons as second rates; those of 1,000 tons or more and below 3,000 tons as third rates; those of less than 1,000 tons as fourth rates.' "

18. The then Secretary of the Navy addressed certain correspondence to the chairman, Committee on Naval Affairs, House of Representatives, wherein he referred to sections 1529 and 1530 of the Revised Statutes and stated "the classification of naval vessels prescribed in these two sections is obsolete. It was established before the era of steel vessels and rapid-fire breech-loading ordnance and is not applicable to a modern Navy * * *." Inasmuch as the presence on the statute books of provisions of law which cannot be observed is objectionable, it is desired that these sections be repealed. In view of the many elements which should be taken into consideration in determining the relative importance of vessels of the several classes, and in consideration of changing conditions affecting not only the vessels themselves but the Navy list also, which may speedily render any fixed rule inapplicable, it is suggested that no absolute classification of vessels or prescription as to command be embodied in the statute, but that, instead, the President be authorized to establish classification of naval vessels and to prescribe appropriate rules governing assignments to command. Such classification and rules would be susceptible of modification from time to time as altered conditions might require." (See Hearing before the Committee on Naval Affairs, 56th Cong., 2d sess., 1901, under

--26--

caption Classification of Naval Vessels.) It was then recommended that the following provision be enacted into law:

"That the President of the United States be and he is hereby, authorized to establish and from time to time modify, as the needs of the service may require, a classification of the vessels of the Navy, and to formulate appropriate rules governing assignments to command of vessels and squadrons."

19. The above provision was offered as an amendment to the act of March 3, 1901, and accepted in lieu of the amended sections of 1529 and 1530, Revised Statutes, hereinbefore quoted, and the same became a part of that law. As a result of this law, the President, in Executive order of June 7, 1901, established a classification of naval vessels, and the classification of naval vessels and the appropriate commands therefore were consequent ly set forth in the Regulations for the Government of the Navy of the United States, 1905, articles 31-39, this being the next issue of the Navy Regulations after the passage of the law, and in all of the classifications of ships officers of the line were designated to command.

20. Again, considering the law and its application to the case at bar, it might also be borne in mind that the legislative intent does not necessarily mean the intention of the person who drafted the law, but must be the intent of the legislature as a whole. From an examination of the correspondence hereinbefore cited, there can be no question as to the intent and the object of the framers of this particular law. Let us, however, examine the law carefully to determine the apparent intent of Congress, which is the determining question.

21. It must be noted that the word "appropriate" is used by Congress in the language of the statute. In construing statutes every word is presumed to have a separate and independent meaning of its own. Congress is not presumed to have used words for no purpose. Accordingly, words cannot be construed as redundant and rejected as surplusage where it is possible to give them full effect. Also, it has been said that "there are many miles of interpretation, but they are of little use; common sense is the best guide." (Walker's Am. L., sec. 17.) The rules by which courts are guided in construing statutes are sanctioned by wisdom and experience of which they are the outgrowth; an examination of these rules will show that "common sense" is generally their foundation.

22. It is considered meet and logical that Congress in using the word "appropriate" intended to include the full import of the word. Webster's New International Dictionary defines "appropriate" as "suitable, proper, fit, to adopt to the purposes intended, to answer the requirements, correct." Therefore it is not believed that it is common sense to consider that Congress intended to raise all its prior restrictive legislation and authorize the

--27--

President to assign anyone to command vessels and squadrons of the United States Navy. Such assignments must be appropriate; i.e., adapted to the purposes intended. It could hardly be said that Congress intended that the President could under that provision of law assign a chaplain in command of a battleship, no matter how excellent the chaplain as such might be, for, as previously stated, it must be borne in mind that if Congress by the act of March 3, 1901, intended to remove all previous restrictive laws as pertained to the duties of staff officers, the above example is a legal possibility.

23. In reference to whether the assignment of a medical officer in command of a hospital ship under certain conditions and subject to certain restrictions would not be an appropriate assignment to command, the Attorney General, in an opinion dated August 24, 1909 (27 Op. Atty. Gen., 571), discussed the provisions of the law of March 3, 1901, in connection with the command of a hospital ship of the Navy and held:

"In the consideration of the various statutes here involved it may be suggested that the act of March 3, 1901, does not expressly repeal prior laws on the subject, and that section 1488, R. S., which declared that the relative rank of officers of the Medical Corps shall not authorize them to 'exercise military command' and the act of March 3, 1899, which abolished the relative rank but provided that the actual rank conferred upon medical officers should not entitle them to 'command in the line or other staff corps,' are still in force. The answer to this is, first, that, assuming the command of a hospital ship is a 'military command,' these words in section 1488 have been supplanted by the later act of March 3, 1899, which provides that medical officers shall not 'command in the line or in other staff corps'; and, second, that the command of a hospital ship by a medical officer is not a 'command in the line or in other staff corps.' It is command in the medical officer's own staff corps, and in their own staff corps medical officers have always had a command." (Sec. 1136, Navy Reg., 1905; sec. 1004, Navy Reg., 1909.) And further on he states:

"It was clearly not contemplated by these regulations or orders that there should be any line officer or regularly enlisted man other than in the Hospital Corps as any part of the complement of the hospital ship. The medical officer in command, therefore, is given no command in the line of the Navy or in any other staff corps."

24. That Congress has consistently considered that staff officers have not the right to exercise military command in the line or other staff corps is indicated by further enactments of Congress where they have in certain instances removed this restriction. For example, in the act of 24 June, 1910 (36 Stat., 614), it provided:

--28--

"That line officers may be detailed for duty under staff officers in the manufacturing and repair departments of the navy yards and naval stations, and all laws or parts of laws in conflict herewith are hereby repealed."

The Judge Advocate General of the Navy, in an opinion dated 18 January, 1915 (5038-20:1), in rendering an opinion on the effect of this law, held:

"This provision was very restricted in its scope, limiting the detail of line officers under staff officers to the manufacturing and repair departments of navy yards and naval stations. In other words, the act of 1910 had the same effect as if it had specifically stated that line officers may not be detailed for duty under staff officers except in the manufacturing and repair departments of the navy yard and naval stations."

Also the following provision contained in the act of 30 June, 1914 (38 Stat., 392), and repeated in the act of 3 March, 1915 (38 Stat., 930):

"* * * Officers of the Construction Corps shall be eligible for any shore duty compatible with their rank and grade to which the Secretary of the Navy may assign them."

Thus in the law last above cited Congress, in removing the restriction upon the duty to be assigned officers of the Construction Corps, provided that that duty on shore should be "compatible with their rank and grade." In other words, it carefully limited its scope to such assignments as were

--29--

compatible with their rank and grade did not go so far as to authorize the assignment of a construction officer to duty as a medical officer of a station; similarly, it did not authorize the assignment of a construction officer to line duties, although in assigning him to construction duties line officers might be assigned to duty under him.

25. Under the caption "Authority of staff officers," article 153(2), Navy Regulations, 1920, stated:

"They shall not, by virtue of rank and precedence, have any additional right to quarters, nor shall they have authority to exercise command except in their own corps and except as provided in articles 170 and 171; * * *"

Article 170 provides that a medical officer may command a hospital ship, and article 171 provides that line officers may be detailed to duty under staff officers in the manufacturing and repair departments of navy yards and naval stations. Article 667 provides "that hospital ships shall be governed by the provisions of the Navy Regulations, so far as they apply, of the laws of the United States, and of The Hague convention," etc. The Navy Regulations of 1920, insofar as they contain subject matter pertaining to hospital ships, are very meager and inadequate to definitely determine and outline their status. On the other hand, the Navy Regulations, 1913, which were superseded by the Navy Regulations, 1920, are very complete and clearly outline the exact status of hospital ships and the duties of all on board. It is pertinent to note that the orders to both Commander ________ and Lieut. Commander ________ were issued during the time the 1913 regulations were in force.

Article 2914 of the Navy Regulations, 1913, provides:

"A hospital ship, being assimilated to a naval hospital on shore, shall be commanded by a naval medical officer not below the grade of surgeon, such commanding officer being detailed by the Navy Department. Such vessels shall be manned by a merchant crew and officers, and in addition by a detail from the Hospital Corps of the Navy, the latter to be employed in carrying out the duties for which the vessel is especially assigned."

These regulations further outline the duties of the master of the hospital ship as having full and paramount control of the navigation of the ship and full responsibility for the discipline and efficiency of the civilian officers and crew.

26. It is a well-settled rule of judicial construction that the regulations issued by the Secretary of the Navy in conformity with section 1547 of the Revised Statutes are valid and have the force of law when they are not inconsistent with the statute under which they are issued by the Secretary.

--30--

(25 Op. Atty. Gen., 270, 274.) However, it is not considered that any question need arise as to the legality of the regulations of the United States Navy as they are not necessarily contrary to existing law.

The laws of the United States bearing on the case at bar have been hereinbefore cited and discussed; so, also, the pertinent parts of the Navy Regulations approved by the President of the United States have been quoted. Thus it will be seen, at the time the orders to the commanding officer and to the accused were issued, neither the law nor the regulations contemplated the commanding officer an officer of the staff corps exercising military command in the line or in other staff corps, or, in other words, Commander __________, exercising military command over the accused.

27. General Order 541 of the series of 1913, the current "Ship's data, U.S. naval vessels," and the current Navy Directory all classify a hospital ship as an auxiliary. The act establishing the Naval Reserve Force (act of Aug. 29, 1916) provides:

"Hereafter, in shipping officers and men for service on board United States auxiliary vessels, preference shall be given to members of the Naval Reserve Force, and after two years from the date of approval of this act, no person shall be shipped for such service who is not a member of the Naval Reserve Force."

It will be borne in mind that the above law applied to all naval auxiliary vessels, of which a hospital ship was but one, and in providing officers and crew for the hospital ship it was therefore necessary to order naval reserves on active duty to these ships; but, on the other hand, to conform to the law and the then existing regulations, it was necessary that the naval reservist crew of the hospital ship must be on inactive duty, thereby complying with article 2914 of the Navy Regulations, 1913, that the crew be a merchant crew and also complying with the law in all respects.

28. From a careful examination of the Navy Regulations, 1920, which superseded the previous existing regulations, there appears to be no specific provisions whatsoever to cover the question of the crews of hospital ships and the duties of the personnel thereof. On the other hand, the Navy Regulations of 1920 specifically limit the authority of medical officers not to command in the line and other staff corps (art. 153(2)), except as provided in article 170, which states medical officers may command hospital ships and, furthermore, article 667, which states that "hospital ships shall be governed by the provisions of the Navy Regulations, so far as they apply, of the laws of the United States," etc., thereby clearly limiting the command of hospital ships to comply with the laws and regulations.

29. From the foregoing, it will be seen that the situation arising in this case presents peculiar conditions, for it appears in fact that the accused, a

--31--

line officer, was serving on the hospital ship commanded by a medical officer. Thus it will be seen that the conditions as existing in this case are different from those that existed at the time of the Attorney General's opinion (27 Op. Atty. Gen., 571) hereinbefore quoted, where he stated that the medical officer in command was not exercising a command in the line but a command in his own staff corps as the crew was a merchant crew and therefore he could legally command. Furthermore, when medical officers were initially placed in command of hospital ships by the President of the United States, acting in his capacity as Commander in Chief, it was not contemplated by him that line officers would be attached thereto. President Roosevelt, in issuing the order to place medical officers in command of hospital ships (Jan. 4, 1906), stated, "and no line officer should be aboard it."

30. In view of the foregoing remarks, it appears conclusive that medical officers cannot exercise command in the line or other staff corps, either by law or existing regulations, and, therefore, the accused was not guilty of having disobeyed the lawful order of his superior officer.

The accused, when arraigned on the charge and specification thereunder, demurred thereto on the ground that the order as given by Commander * * * to the accused was not a lawful order, and, therefore, in view of the foregoing remarks, the court erred in finding the charge and specification in due form and technically correct, for the reason that the order was not a lawful order. It is further noted that the specification alleges, when the offense was committed on March 13, 1921, "the United States then beeing in a state of war." This allegation was incorrect, by virtue of Alnav 26, wherein it was stated, interalia, that "the averment 'the United States then being in a state of war' will be omitted in specifications of offenses committed on or after March third, 1921."

31. In view of the foregoing, * * * the proceedings, findings, and sentence of the general court-martial in the case of Lieut. Commander * * *, United States Naval Reserve Force, were disapproved and the accused released from arrest and restored to duty.

--32--

[END]