The Navy Department Library

THE BATTLES OF Cape Esperance, 11 October 1942 AND Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942

PDF Version [28.5MB]

Cover: Near Miss, watercolor, by Dwight C. Shepler. Dropping out of low squall clouds, Japanese dive-bombers penetrated a curtain of antiaircraft fire, narrowly missing the USS San Juan with a high explosive bomb. Aboard the cruiser, which was screening the starboard side of the aircraft carrier Enterprise, this scene was painted during the third attack of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942.

THE BATTLES OF

Cape Esperance

11 October 1942

and

Santa Cruz Islands

26 October 1942

NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

1944

Foreword to the NHC Edition

The Battle of Cape Esperance and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands comprise one of a series of twenty-one published and thirteen unpublished Combat Narratives of specific naval campaigns produced by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War II. Selected volumes in this series are being republished by the Naval Historical Center as part of the Navy’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of World War II.

The Combat Narratives were superseded long ago by accounts such as Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II that could be more comprehensive and accurate because of the abundance of American, Allied, and enemy source materials that became available after 1945. But the Combat Narratives continue to be of interest and value since they demonstrate the perceptions of naval operations during the war itself. Because of the contemporary, immediate view offered by these studies, they are well suited for republication in the 1990s as veterans, historians, and the American public turn their attention once again to a war that engulfed much of the world a half century ago.

The Combat Narrative program originated in a directive issued in February 1942 by Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, that instructed the Office of Naval Intelligence to prepare and disseminate these studies. A small team composed primarily of professionally trained writers and historians produced the narratives. The authors based their accounts on research and analysis of the available primary source material, including action reports and war diaries, augmented by interviews with individual participants. Since the narratives were classified Confidential during the war, only a few thousand copies were published at the time, and their distribution was primarily restricted to commissioned officers in the Navy.

Following the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in late August 1942, the naval phase of the Guadalcanal Campaign entered a lull which lasted through September. During that period, a pattern developed that

III

prevailed throughout much of the remainder of the operation. In daylight, U. S. forces controlled the waters surrounding Guadalcanal while the Japanese controlled them at night. Under cover of darkness, the enemy conducted resupply and reinforcement efforts, dubbed the “Tokyo Express” by the Americans, which involved the sending of troop transports and escorts down “The Slot”—the naval passageway through the Solomon Islands from Bougainville southeast to Guadalcanal. After completing their escort work, the Japanese warships typically bombarded the Marine perimeter on the northern coast of the island, before heading back up “The Slot” towards Bougainville.

Try as they might, the Japanese never succeeded in gaining the upper hand against the Americans, although they came close to doing so on several occasions. During the September lull at sea, the enemy launched a major attack against the Marine perimeter, producing the second major land engagement of the campaign, the Battle of Bloody Ridge, 12-14 September. The Japanese failure to break through the Marine lines and capture Henderson Field, the Americans’ vital air base, prompted them to step up the “Tokyo Express” shipment of troops to Guadalcanal and to increase their naval bombardment of the airfield. Their efforts did not go unchallenged as an American cruiser-destroyer force advanced against them on the night of 11 October, precipitating the Battle of Cape Esperance, the first engagement described in this narrative.

Two weeks later, the two foes fought another major naval engagement, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, which also is described in this narrative. It was a carrier battle in which the Navy’s Hornet and Enterprise locked horns with a powerful Japanese battleship—carrier fleet.

The Office of Naval Intelligence first published this narrative in 1943 without attribution. Administrative records from the period indicate that Ensign Henry V. Poor wrote the account of the Battle of Cape Esperance and that he coauthored the story of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands along with Lieutenant (jg) Henry A. Mustin and Lieutenant (jg) Colin G. Jameson. All three were Naval Reserve intelligence officers. Poor was a lawyer, diplomat, and author who became Associate Dean of the Yale Law School after the war. Before World War II, Mustin was a journalist with the Washington Evening Star. After the war, he returned to that newspaper and later was associated with the Columbia Broadcasting System, Mutual Broadcasting, and the

IV

Voice of America. Prior to entering the Navy in 1942, Jameson was a free-lance short story writer who had published about 40 stories.

I wish to acknowledge the invaluable editorial and publication assistance offered in undertaking this project by Mrs. Sandra K. Russell, Managing Editor, Naval Aviation News magazine; Commander Roger Zeimet, USNR, Naval Historical Center reserve Detachment 206; and Dr. William S. Dudley, Senior Historian, Naval Historical Center. We also are grateful to Rear Admiral Kendell M. Pease, Jr., Chief of Information, and Captain Jack Gallant, USNR, Executive Director, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps WW II 50th Anniversary Commemorative Committee, who generously allocated the funds from the Department of the Navy’s World War II commemoration program that made this publication possible.

Dean C. Allard

Director of Naval History

v

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D. C.

1 October 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U. S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

{SIGNATURE}

REAR ADMIRAL, U. S. N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence

VI

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publication Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

{SIGNATURE}

E. J. KING

FLEET ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

VII

Charts and Illustrations

BATTLE OF CAPE ESPERANCE

and

BATTLE OF SANTA CRUZ ISLANDS

| Page | |

| Chart: Battle of Cape Esperance | XI |

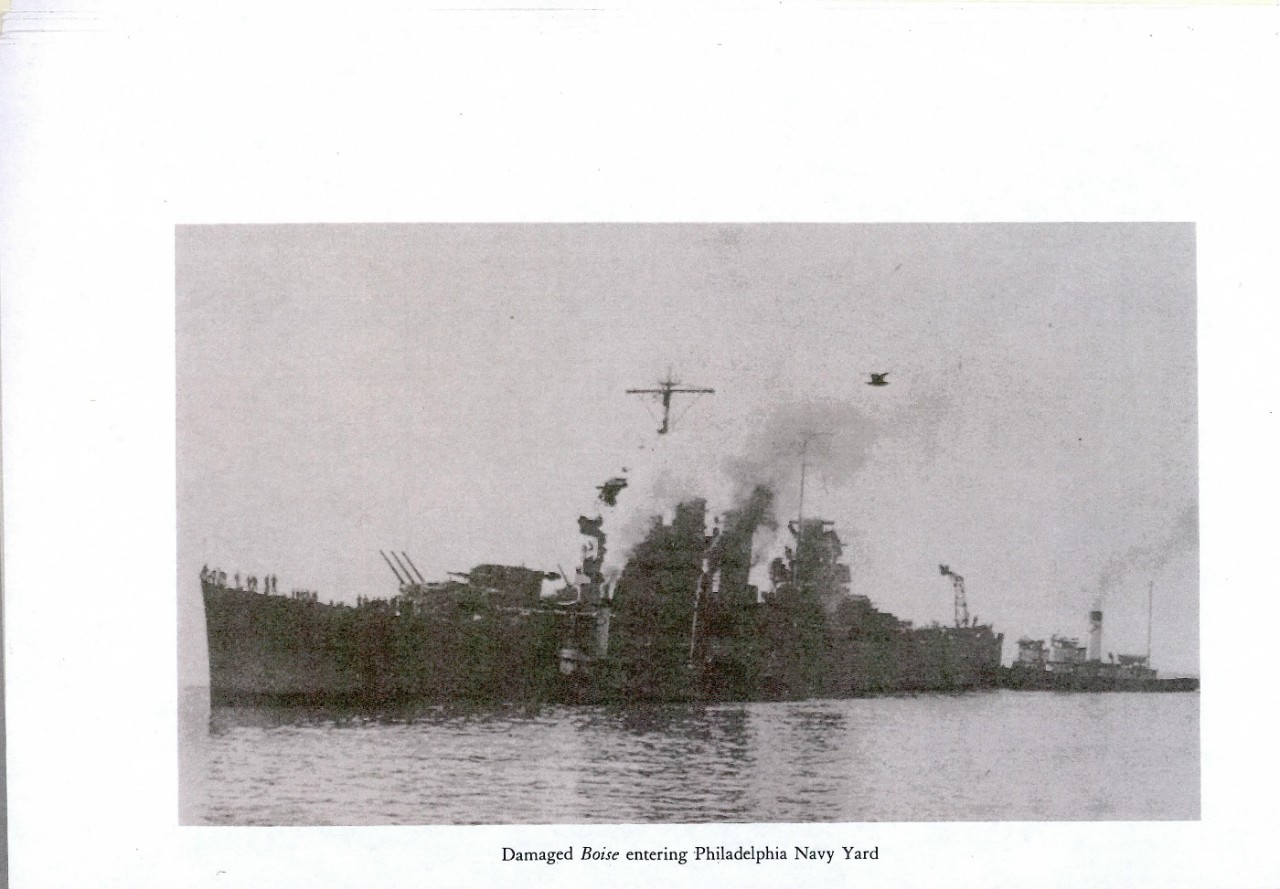

| Illustration: Damaged Boise entering Philadelphia Navy Yard | XII |

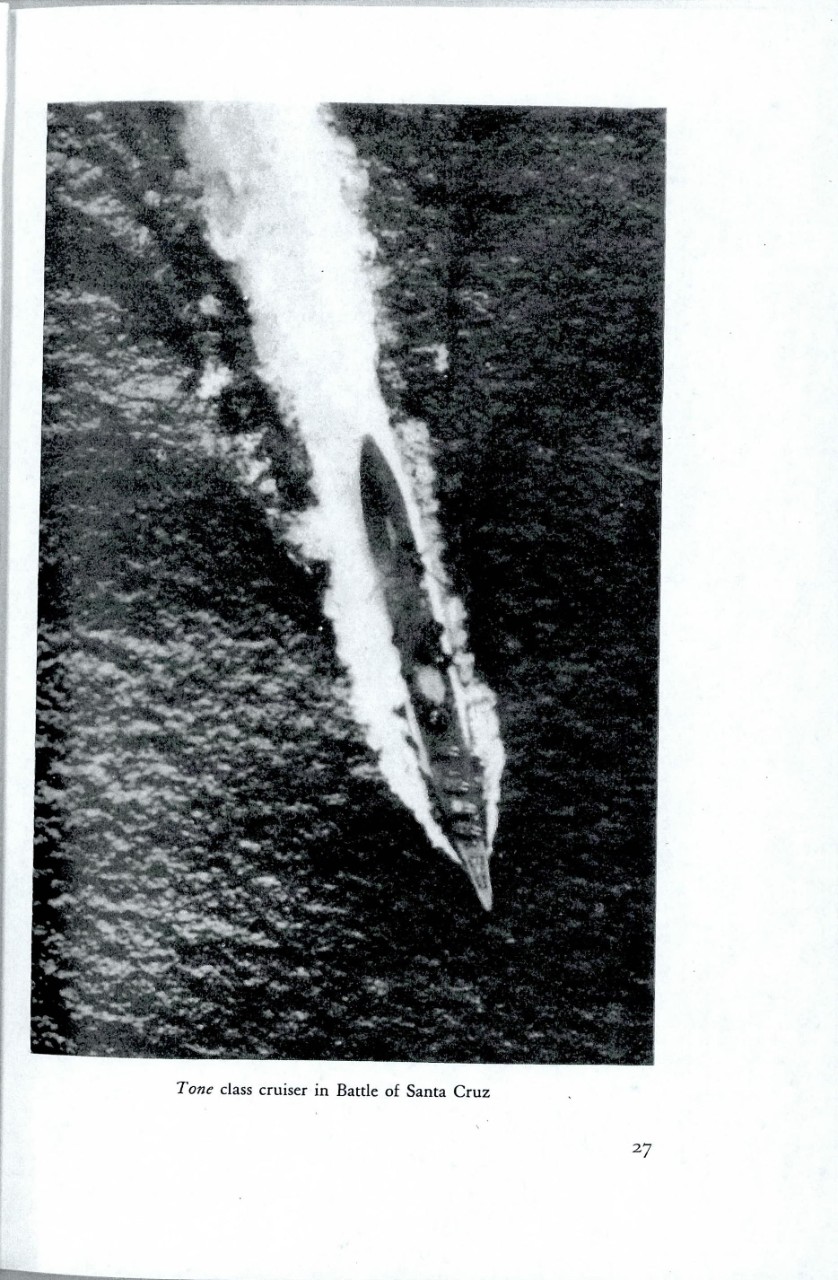

| Illustration: Tone-class cruiser in Battle of Santa Cruz | 27 |

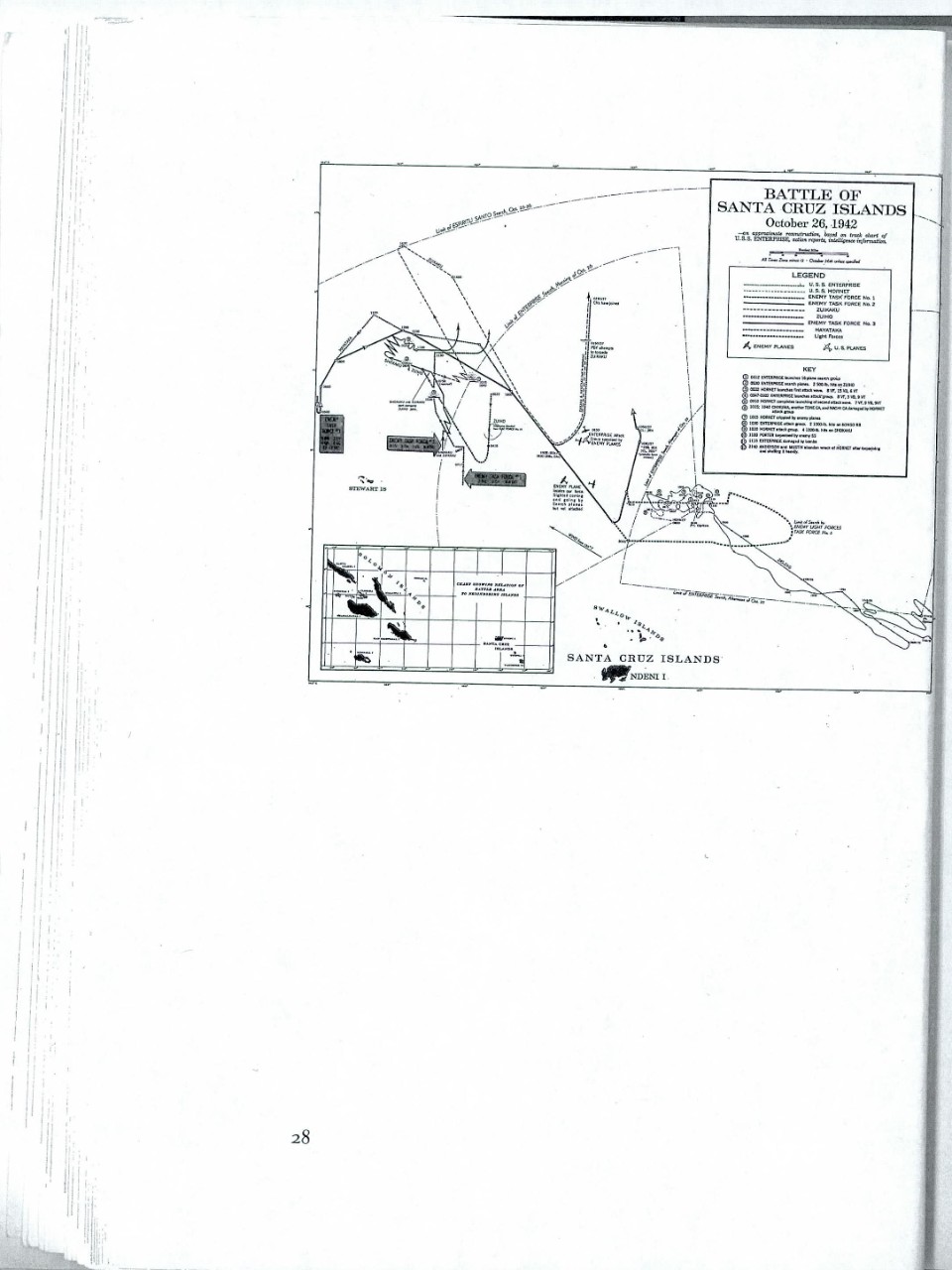

| Chart: Battle of Santa Cruz Islands | 28 |

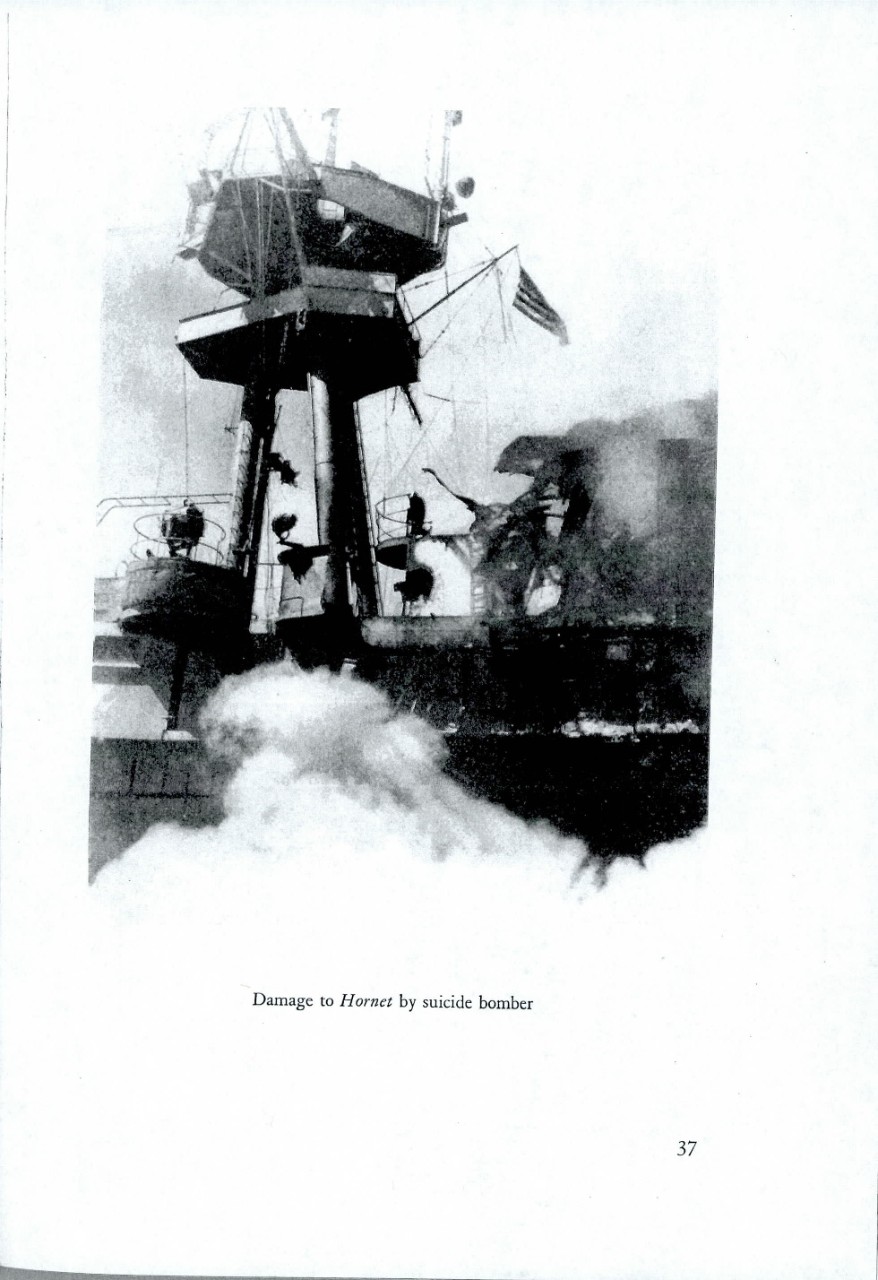

| Illustrations: Damage to Hornet by suicide bomber | 37 |

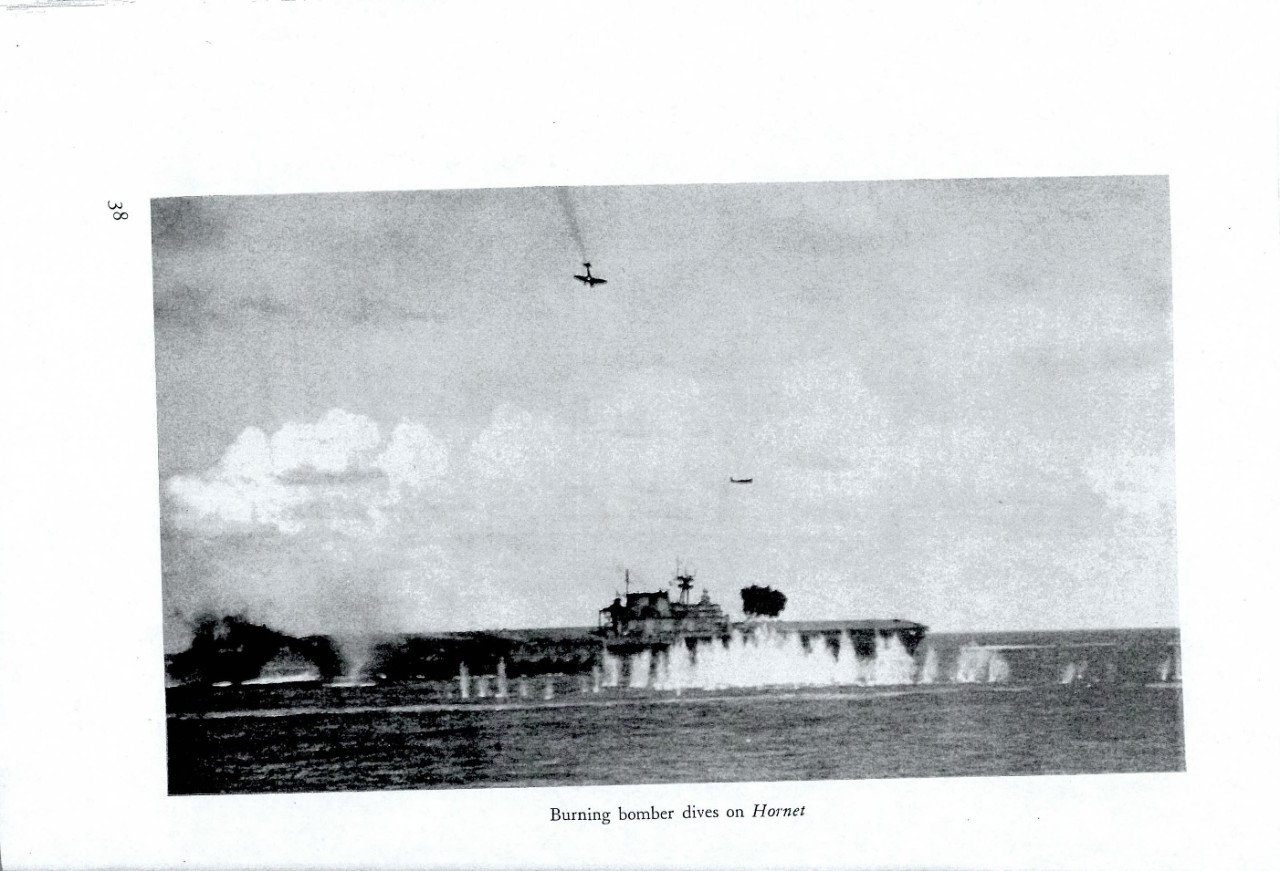

| Burning bomber dives on Hornet | 38 |

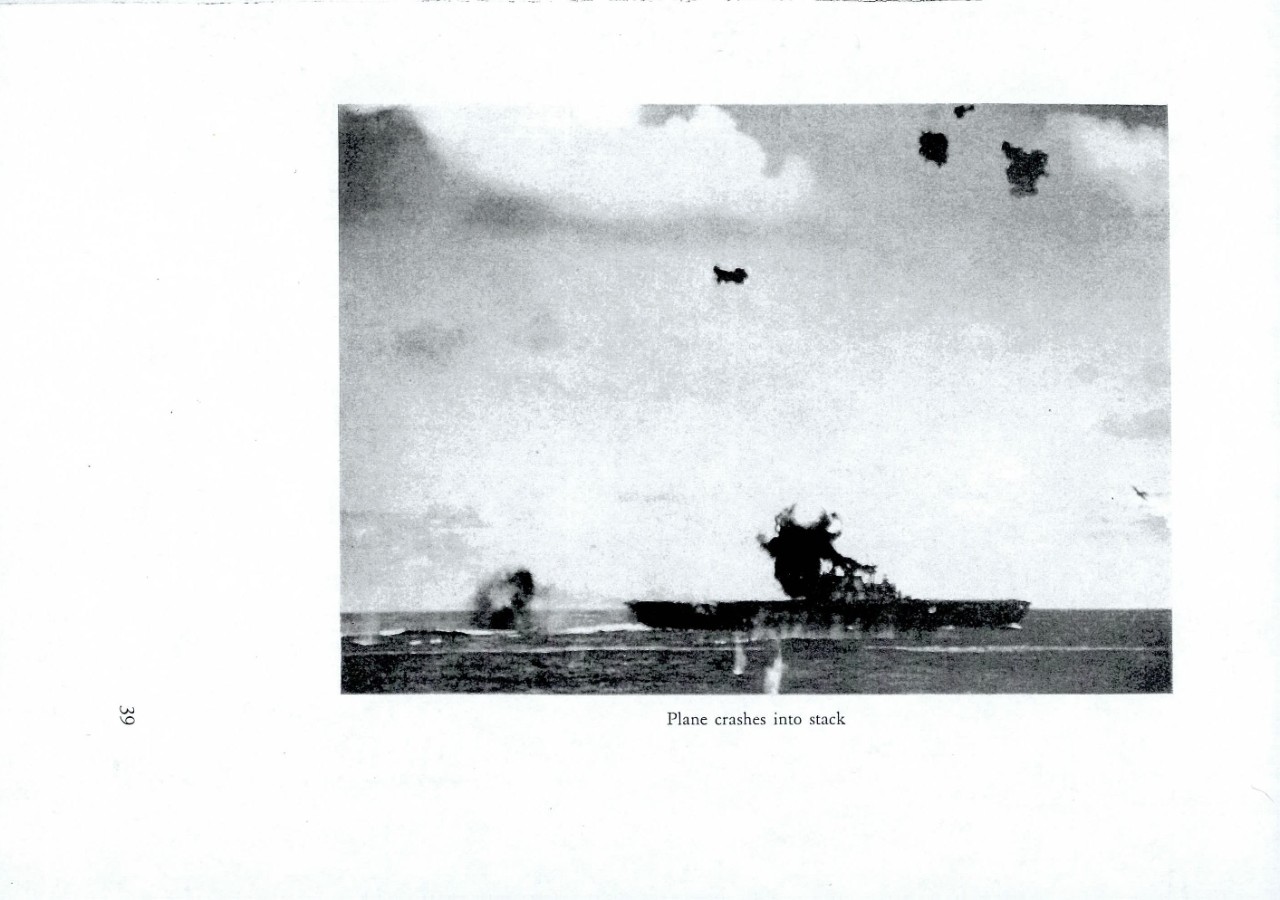

| Plane crashes into stack | 39 |

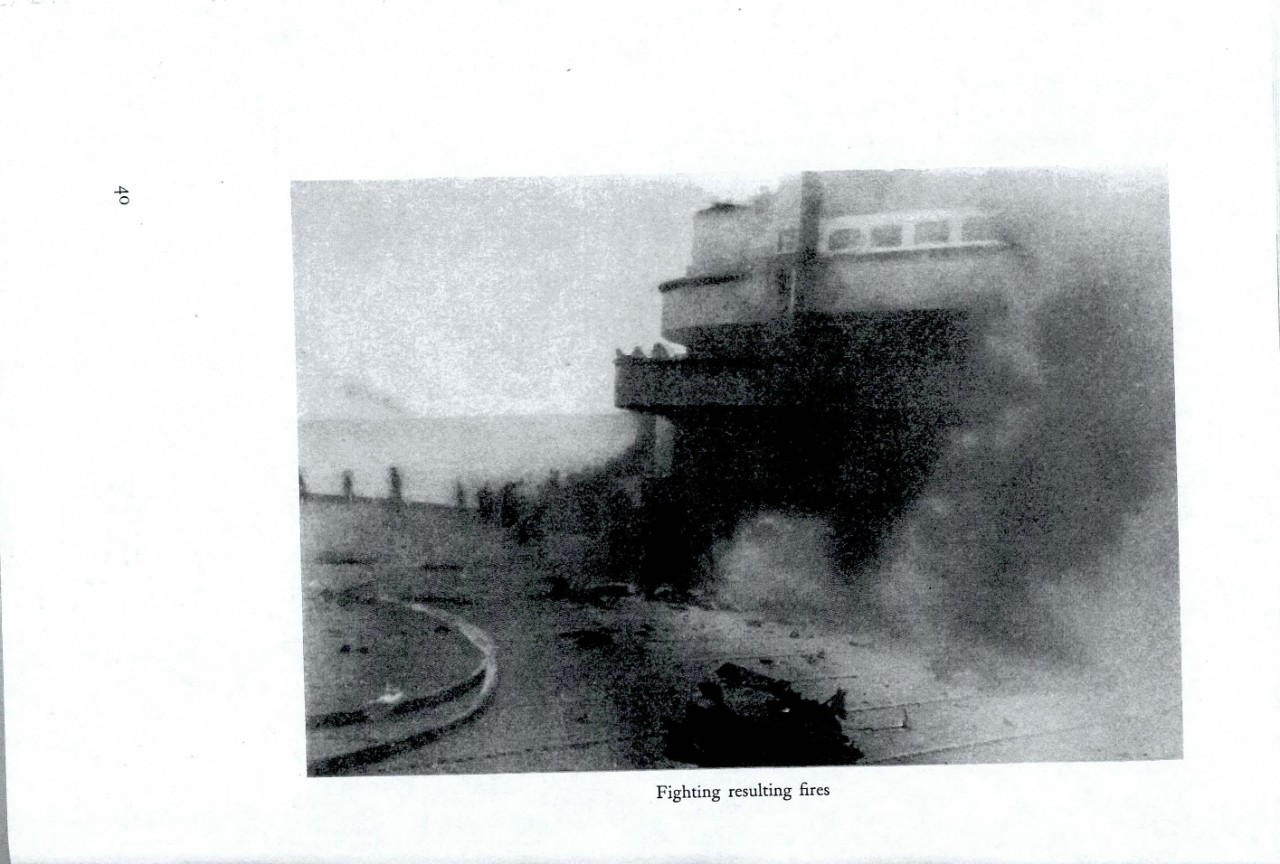

| Fighting resulting fires | 40 |

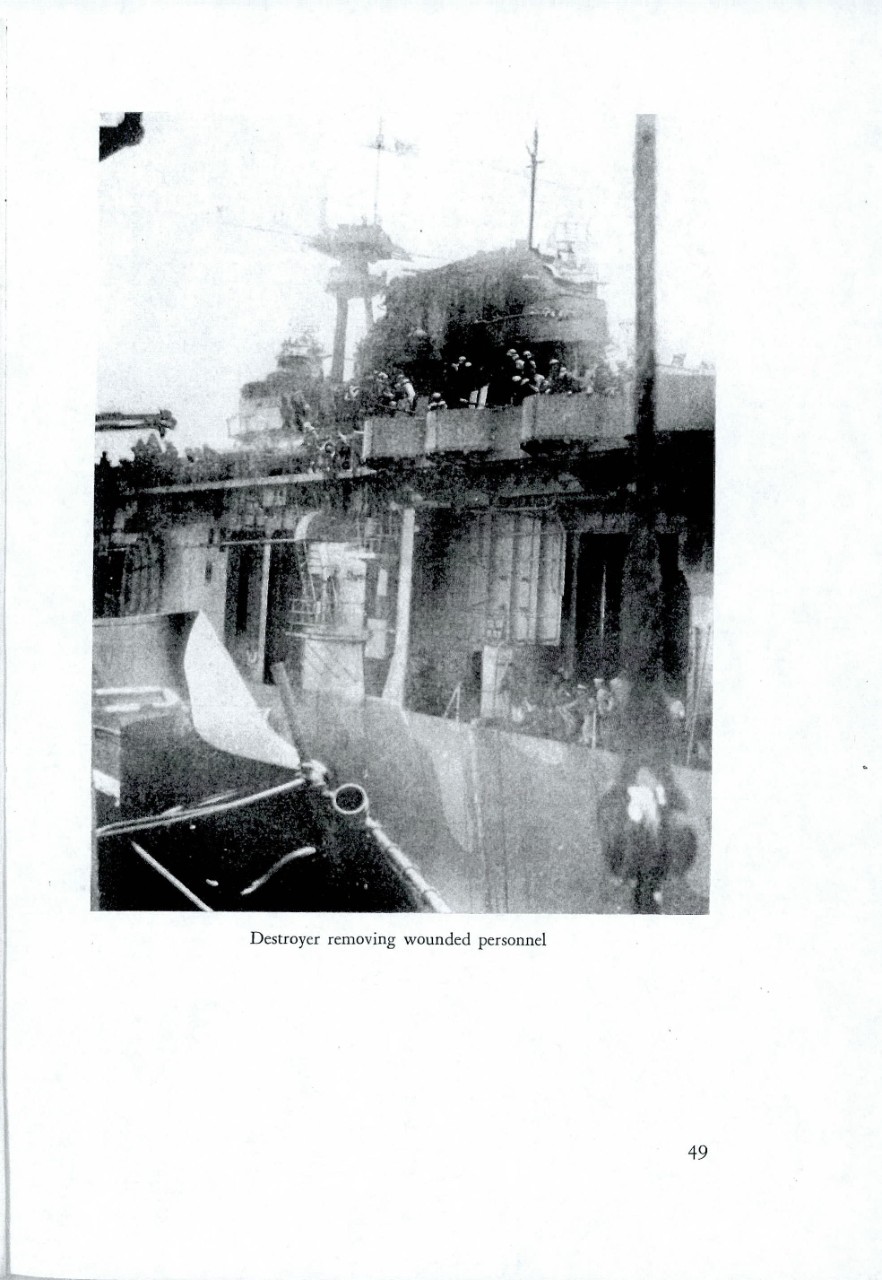

| Destroyer removing wounded personnel | 49 |

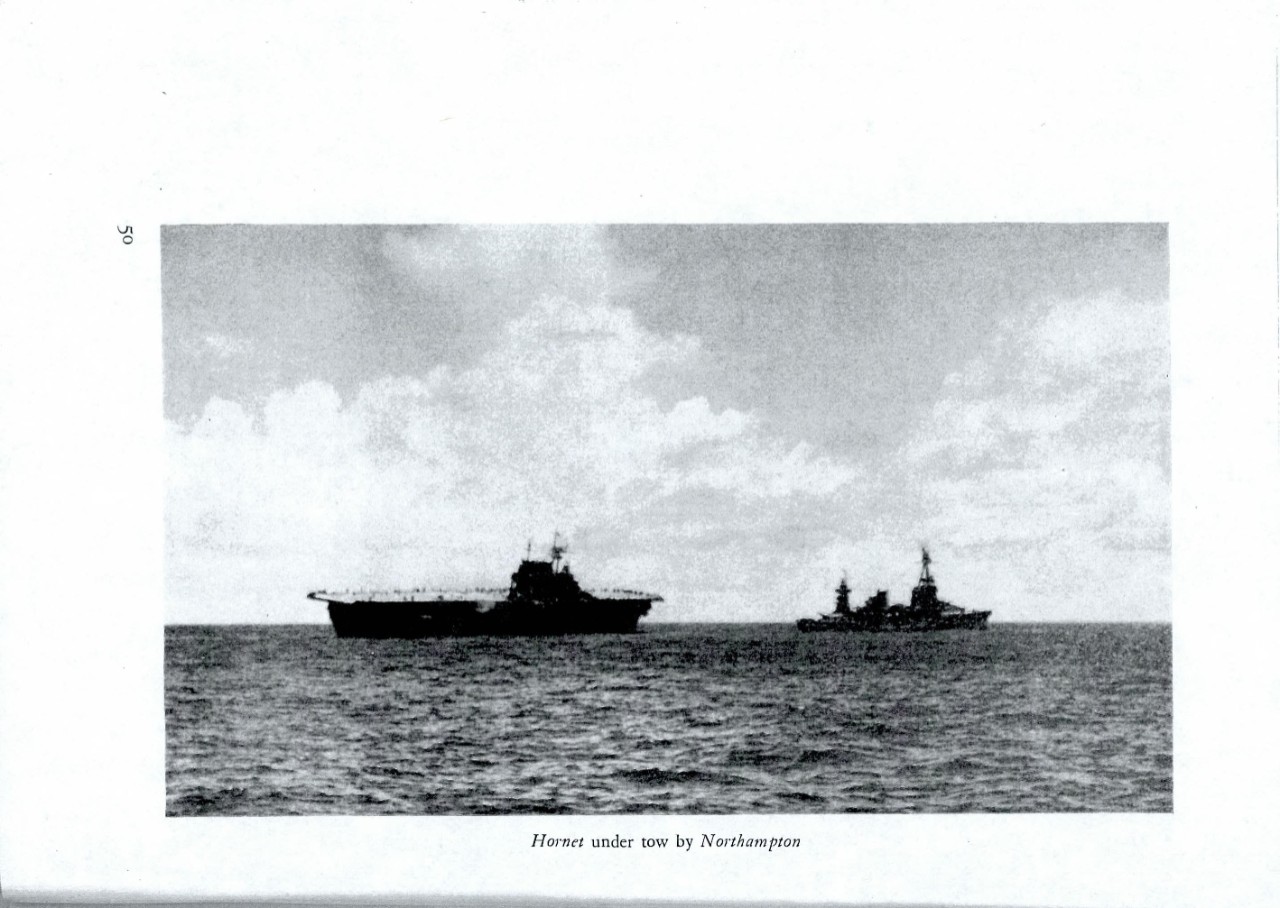

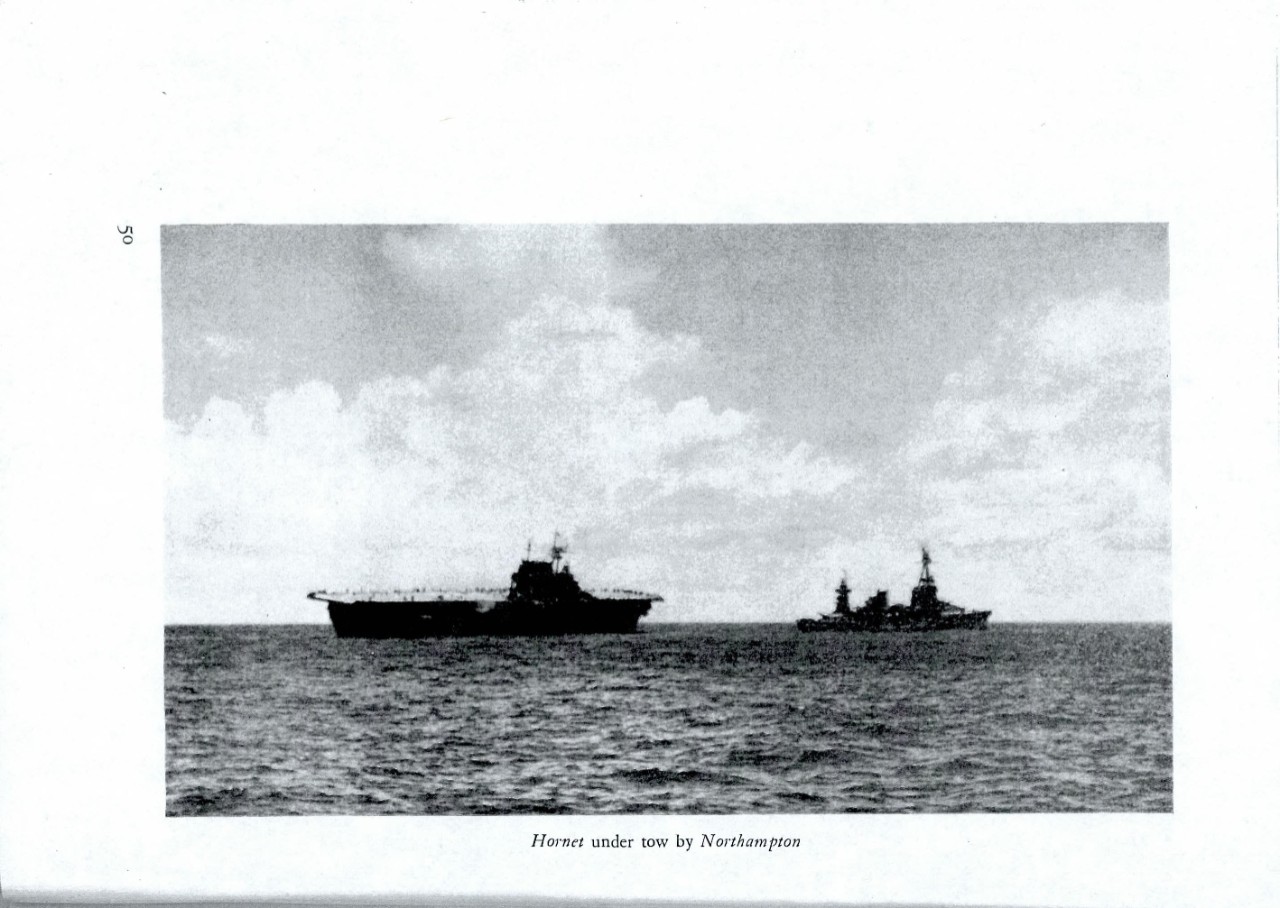

| Hornet under tow by Northampton | 50 |

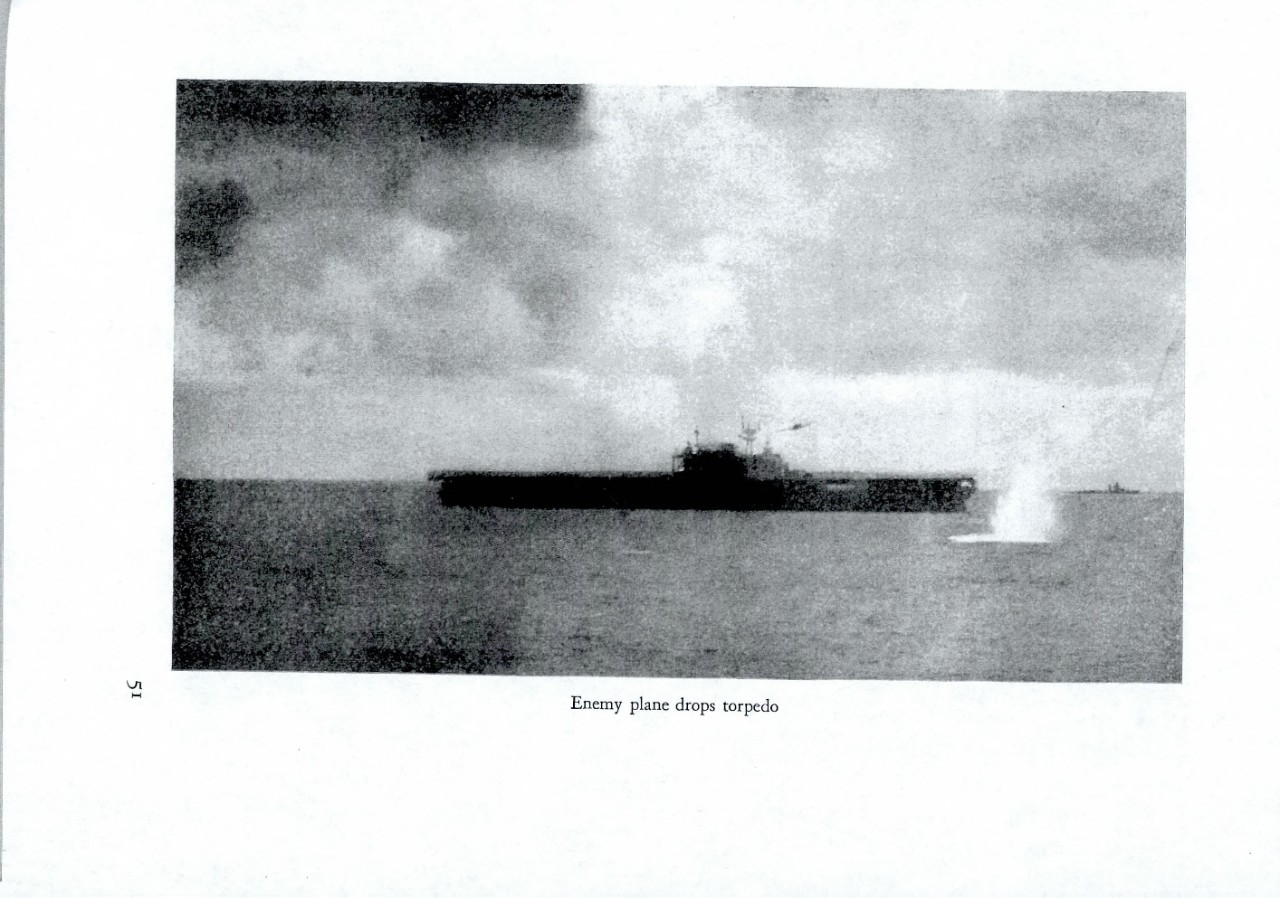

| Enemy plane drops torpedo | 51 |

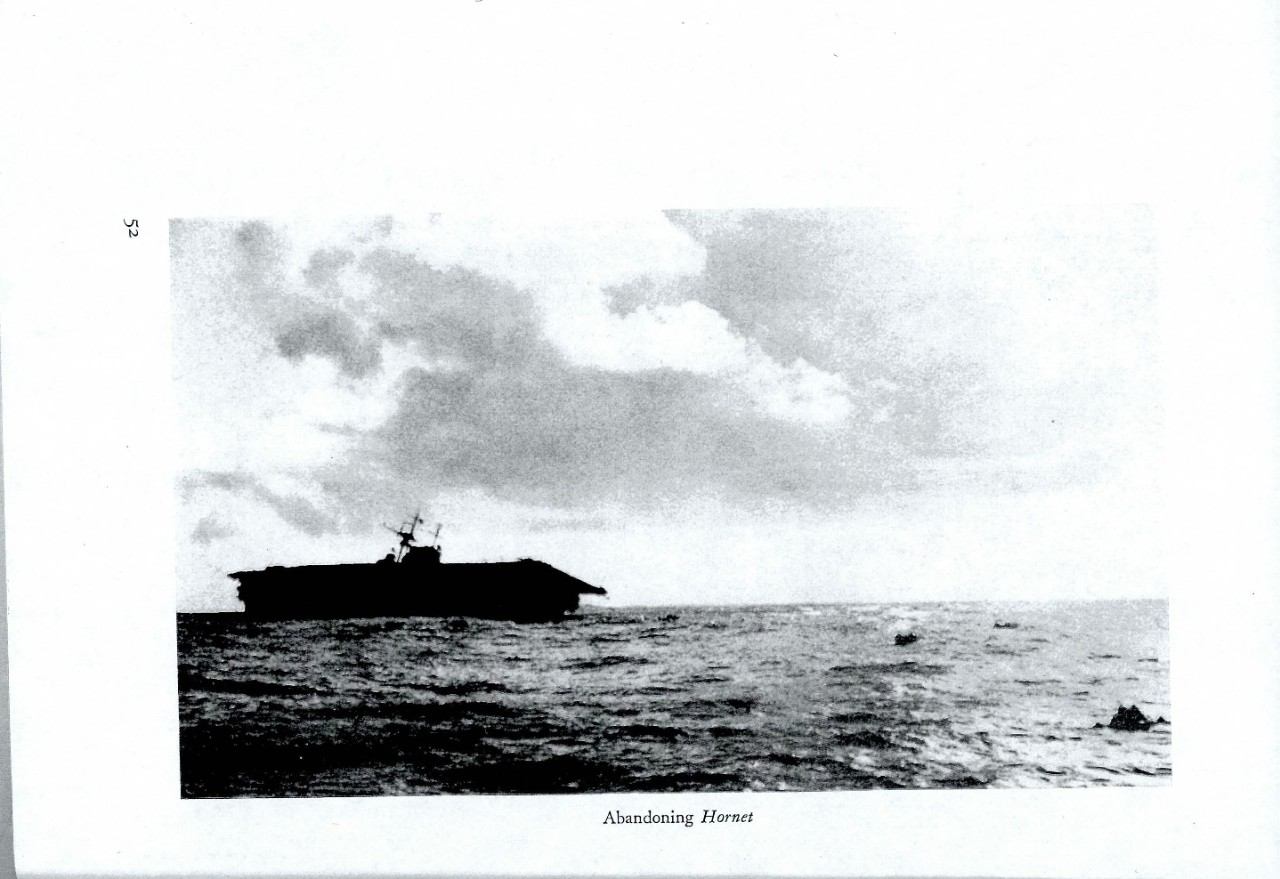

| Abandoning Hornet | 52 |

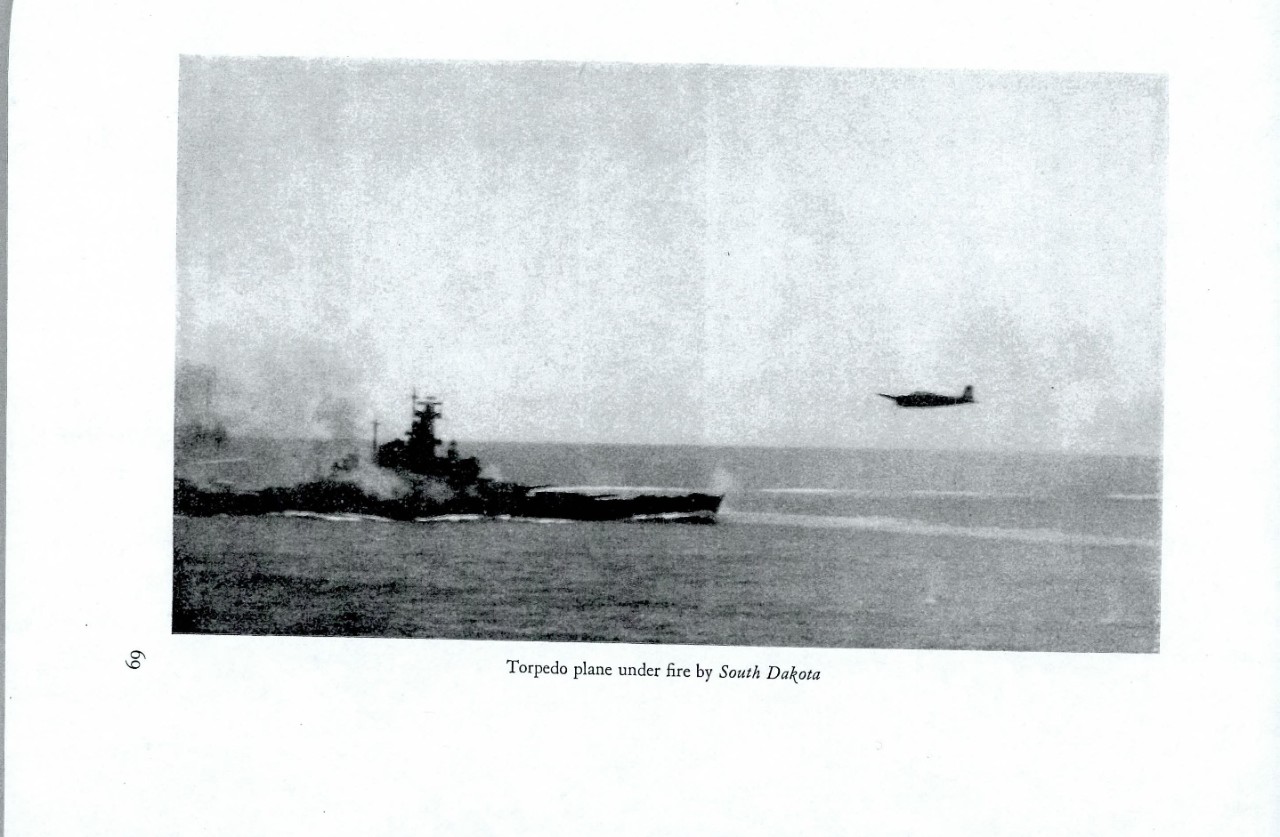

| Torpedo plane under fire by South Dakota | 69 |

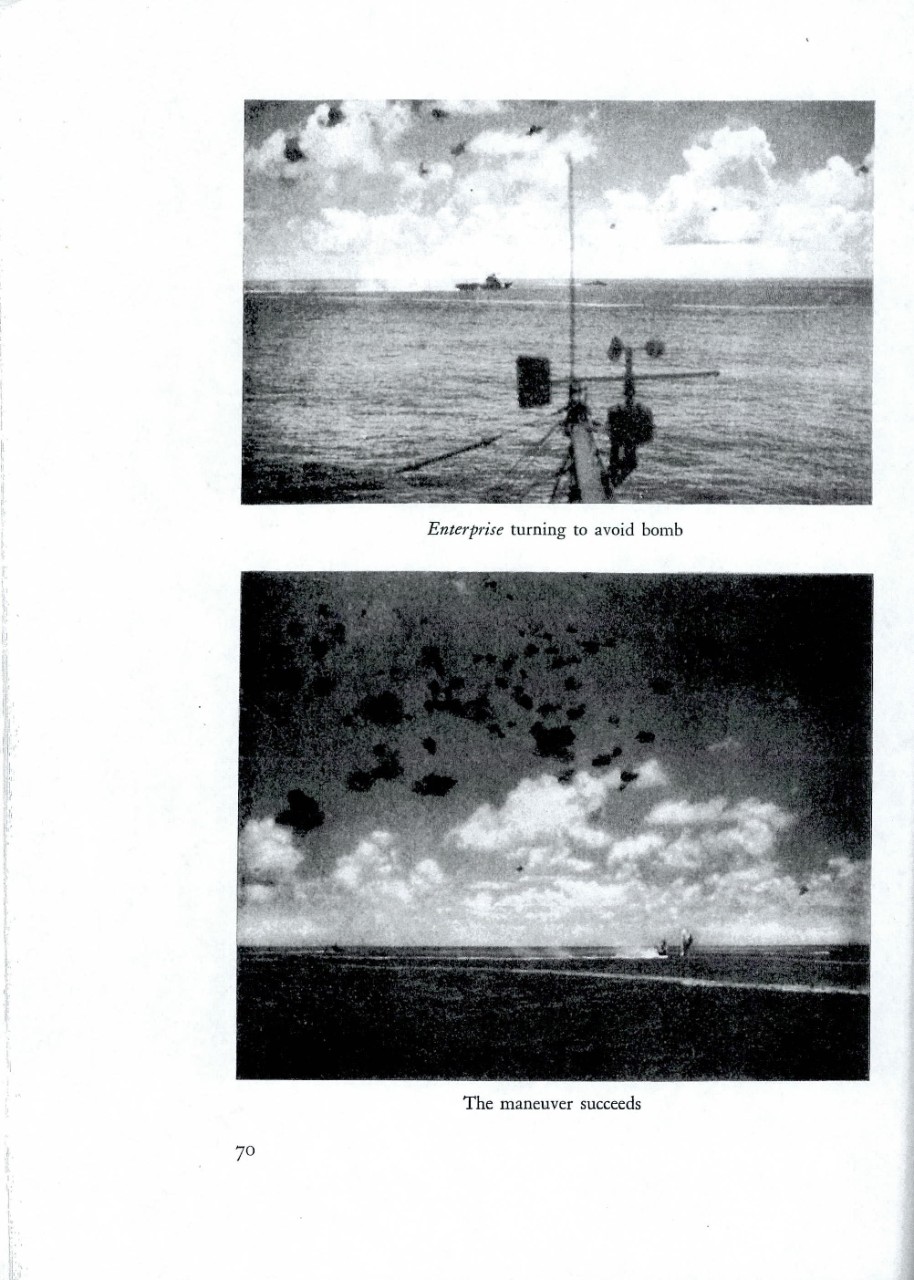

| Enterprise turning to avoid bomb | 70 |

| The maneuver succeeds | 70 |

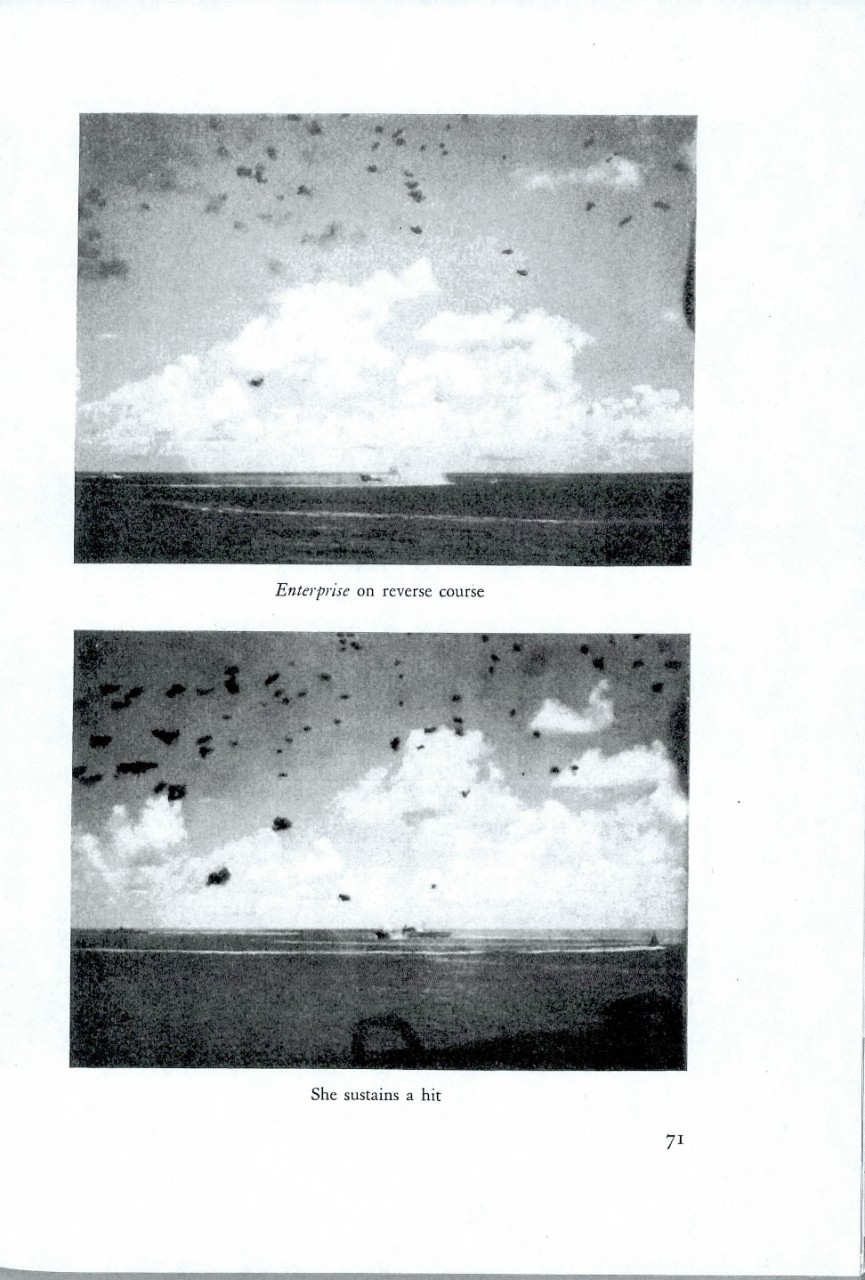

| Enterprise on reverse course | 71 |

| She sustains a hit | 71 |

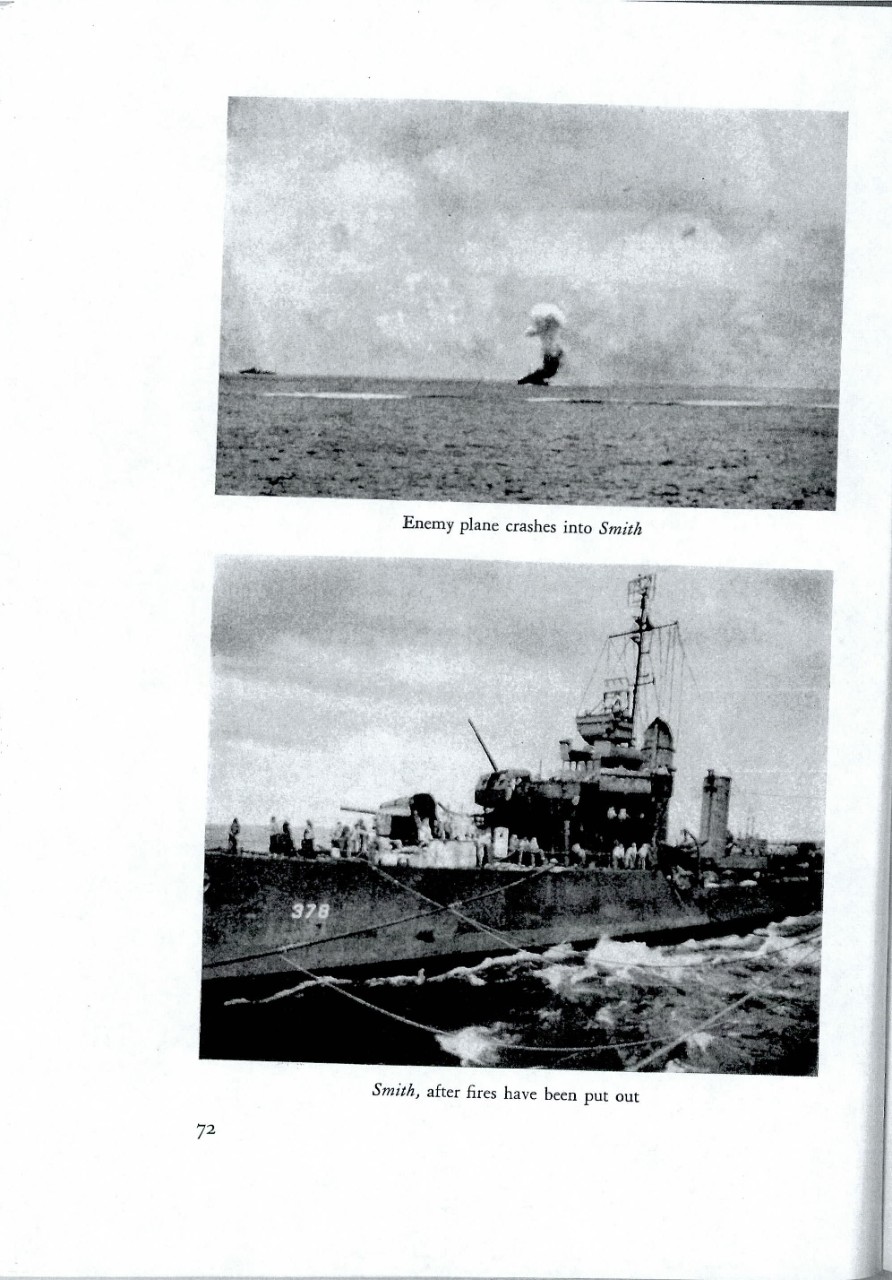

| Enemy plane crashes into Smith | 72 |

| Smith, after fires have been put out | 72 |

VIII

Contents

BATTLE OF CAPE ESPERANCE

| Page | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Organization of our Force | 2 |

| Admiral Scott's instructions | 3 |

| Preliminary movements | 4 |

| 11 October ------events prior to action | 5 |

| The engagement | 12 |

| Retirement | 17 |

| Conclusions | 19 |

| Appendix | 20 |

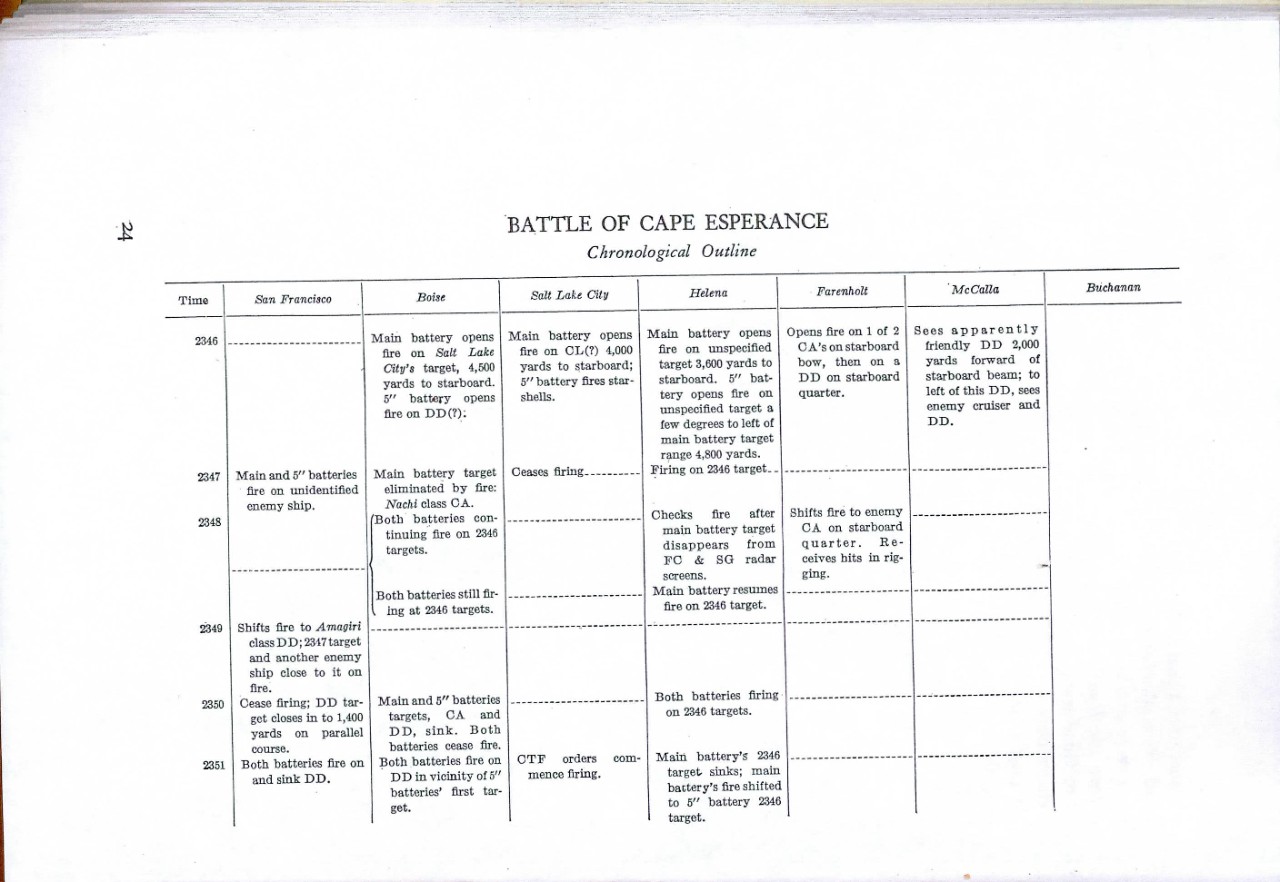

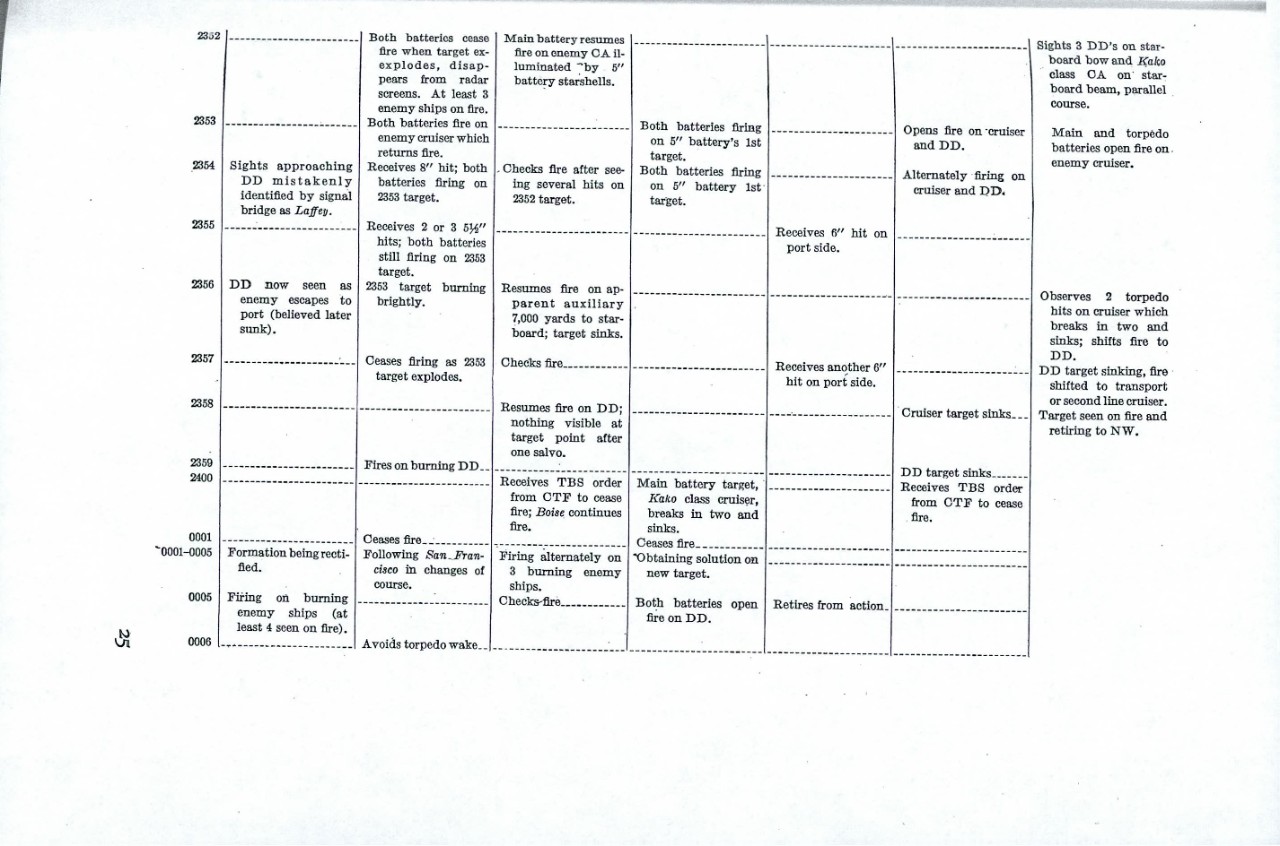

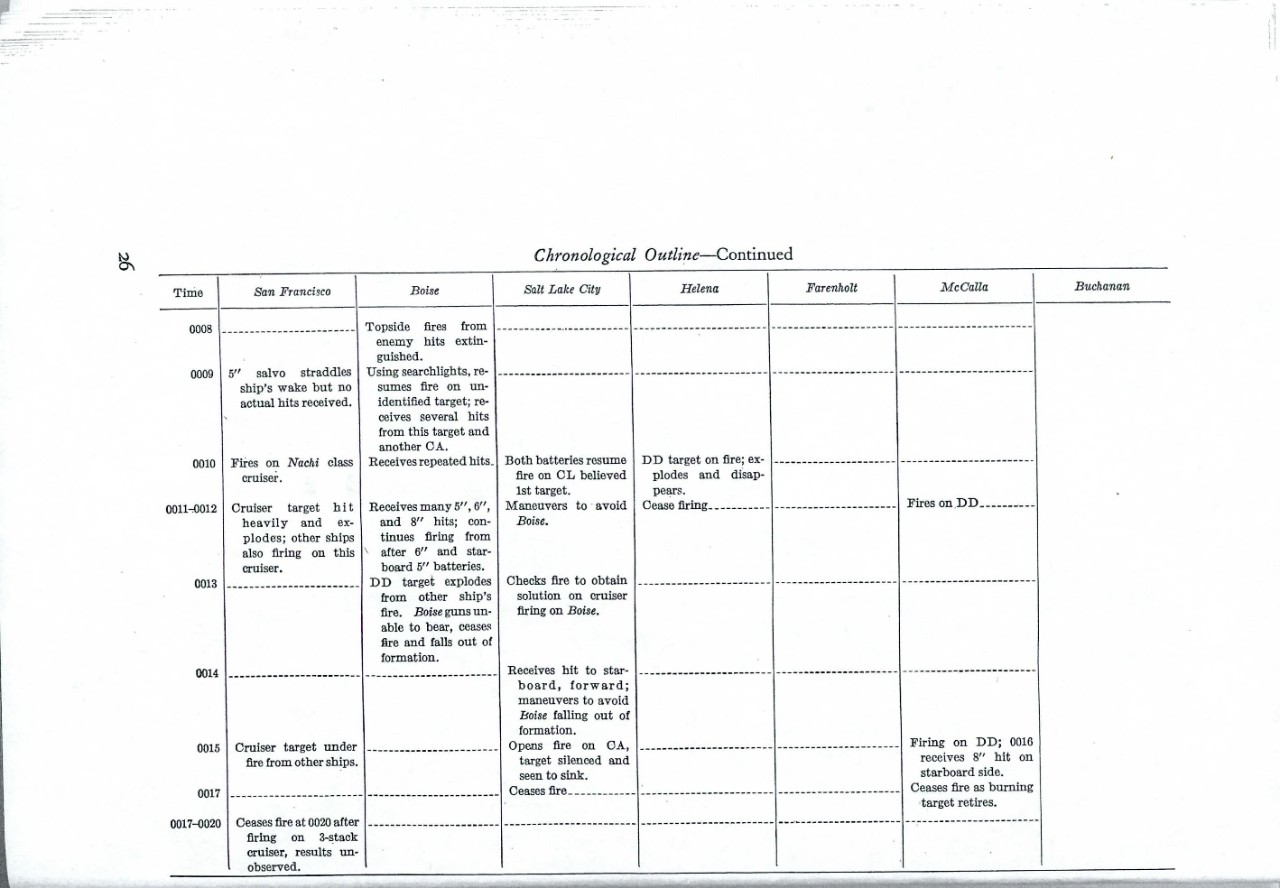

| Chronological outlines | 24 |

| BATTLE OF SANTA CRUZ ISLANDS | |

| Introduction | 29 |

| Forces involved | 30 |

| The approach | 33 |

| Action on Guadalcanal | 34 |

| Results of Enterprise air search | 35 |

| Carried Zuiho damaged | 42 |

| Our Air Group attack | 44 |

| First Hornet wave | 45 |

| Shokaku hit | 46 |

| Nachi cruiser hit | 47 |

| The Enterprise wave | 47 |

IX

| Kongo-class battleship hit |

48 |

| Second Hornet wave | 53 |

| Chikuma hit | 53 |

| Another Tone-class cruiser hit, as well as CL or DD | 54 |

| Summary of damage inflicted on enemy ships | 55 |

| Enemy attacks on the Hornet group | 55 |

| Enemy attacks on the Enterprise group | 62 |

| Summary of damage suffered by Task Force KING | 67 |

| Conclusions | 68 |

| Appendix A: Torpedoing of the Hornet by our destroyers | 73 |

| Appendix B: Lieut. Stanley W. Vjtasa downs seven enemy planes | 75 |

| Appendix C: Designations of United States naval ships and aircraft | 77 |

X

Battle of Cape Esperance

11 October 1942

INTRODUCTION

SCARCELY had American forces consolidated their positions on Guadalcanal after the successful landing of 7 August 1942, when the Japanese indicated their resolve to regain control of the southern Solomons. Although they made no immediate effort to capitalize on their success in the Battle of Savo Island on the night of 8-9 August, strong forces appeared in the vicinity of the Santa Cruz Islands on 24 August. These forces included three and possibly four carriers. They withdrew after a violent attack by our carrier planes in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, 23-25 August, which cost them the carrier Ryujo. 1

For a time after this Japanese defeat, surface actions were confined to minor clashes, chiefly at night, between light destroyer and torpedo boat units. 2 Japanese surface forces attempting to land additional troops and materiel in the Cape Esperance area were continually harassed by planes from Henderson Field.

By mid-October, however, the Solomons had become for both the American and Japanese navies a magnet attracting increasingly large fleet units. The two great battles which assured the United States at least temporary control of the South Pacific were still distant 2 weeks and a month respectively, but they were clearly imminent. Neither side felt able to dominate the southern Solomons with the forces then on Guadalcanal; nether had marshalled sufficient strength to challenge the other to a full-size engagement; yet both were determined to fight, and by the end of the first week in October both were ready to risk their heaviest naval units.

During the latter part of September and early October, the Japanese were concentrating surface units in the Shortlands area, and sending them.

-----------------------

1 See Combat Narratives, “The Landing in the Solomons,” “The Battle of Savo Island,” “The Battle of the Eastern Solomons.”

2 See Combat Narrative, “Miscellaneous Actions in the South Pacific.”

I

south toward Guadalcanal—through the inside passage between New Georgia, Choiseul and Santa Isabel Islands—so as to reach the northwest tip of Guadalcanal, Cape Esperance, at night. These ships would debark reinforcements, or bombard our Henderson Field positions, and retire by daybreak.

To consider means of halting these reinforcements and raids, which increasingly threatened our Solomons positions, a conference was called at Espiritu Santo. Our available surface forces in the South Pacific were few, and plans for the heaviest of them had already been laid. A large convoy with Army reinforcements for Guadalcanal was soon to depart from Noumea. By 11 October it would be about 250 miles west of Espiritu Santo. Task Force KING,3 which included the aircraft carrier Hornet, was to support the convoy to the westward. Protection to the east was to come from a battleship-cruiser force, built around the Washington, which was expected to assume a position east of Malaita.

ORGANIZATION OF OUR FORCE

Based at Espiritu Santo, however, was Task Force SUGAR, commanded by Rear Admiral Norman Scott, and organized as follows:

2 heavy cruisers:

San Francisco, (F), Capt. Charles H. McMorris

Salt Lake City, Capt. Ernest G. Small

I light cruiser:

Boise, Capt. Edward J. Moran

3 destroyers, Capt. Robert G. Tobin

Farenholt, Lt. Comdr. Eugene T. Seaward

Buchanan, Comdr. Ralph E. Wilson

Laffey, Lt. Comdr. William E. Hank

The Task Force as thus constituted was too small for effective operations against the enemy units likely to be encountered. It was augmented therefore by three other ships operating in the vicinity of Espiritu Santo: the light cruiser Helena (Capt. Gilbert C. Hoover), and the destroyers Duncan (Lt. Comdr. Ennis W. Taylor) and McCalla (Lt. Comdr. William G. Cooper).

If dispatched within the new few days, this force would, when off the southern shore of Guadalcanal, exert a protective influence on the left

--------------------

3 Task force numbers have been omitted from Combat Narratives for reasons of security. In their stead the Navy flag names for the first letter of the surnames of the commanding officers are used.

2

flank of the Army convoy moving toward that island, even though not connected with the convoy in an operational sense. 4 Since its creation as a separate unit on 20 September, it had engaged only in target practice.

Accordingly, Task Force SUGAR was ordered to sortie from Espiritu Santo on 7 October, and steam to a point in the neighborhood of Rennell Island, from which, upon receipt of air search information that enemy units were moving towards Guadalcanal, it would proceed to the Savo Island area in time to intercept them. Its stated mission was to “search for and destroy enemy ships and landing craft.”

ADMIRAL SCOTT’S INSTRUCTIONS

Task Force SUGAR’s operational plans were contained in a memorandum issued by Admiral Scott on 9 October, 2 days out of Espiritu Santo.

Provided the horizon was visible, each cruiser was to launch two planes to scout the shore line of Guadalcanal for enemy landing operations, and offshore for supporting forces. The aircraft were to endeavor to maintain contact with the enemy until the approach of the Task Force, then to dry bombs and float-lights to indicate the enemy’s position. Planes were to report any information regarding the enemy, even though negative. Flares were not to be used unless expressly ordered by Admiral Scott. Upon the completion of their mission, or in the event that tactical scouting was impossible, the planes were to proceed to Tulagi, fuel at daybreak, and report their readiness to Admiral Scott via the commanding general on Guadalcanal, who would inform them of the point for a rendezvous with Task Force SUGAR. Radio was to be used for essential messages.

Concerning the formation of his surface ships, Admiral Scott specified that the cruisers were to “form DOG,” 5 in order to facilitate signals, with the destroyers divided two ahead and two astern of the cruisers. The destroyers were instructed to illuminate targets as soon as possible after radar contacts, to fire torpedoes at large ships and direct shell fire at enemy destroyers and small craft. The heavy cruisers were to use continuous fire against small ships at short range, rather than full gun salvos with long intervals. The third and fourth cruisers in the column (the

-------------------

4 Troops and supplies from this convoy were disembarked at Guadalcanal without incident the afternoon of 13 October.

5 Take formation, column, open order.

3

Salt Lake City and the Helena) were, with the destroyers, to keep watch on the disengaged flank, and to open fire without orders from Admiral Scott.

The van destroyers were cautioned to observe changes of course by the cruisers should TBS6 fail, and to be alert for turn signals by TBS or blinker. They were specifically warned to keep the TBS adequately manned and the circuit as clear as possible. Emphasizing that Japanese gunfire would quickly follow searchlight illumination, Admiral Scott advised the use of counter-illumination and opening fire without delay. He added that the danger of silhouetting one’s own ship should be borne in mind.

Blinker tubes were to be dimmed, and to show blue or red lights; white lights were to be used only when necessary. TBS silence was to be maintained as long as feasible, although all ships were authorized to use TBS to report contacts.

Ships compelled to fall out of formation should do so on the disengaged flank, and proceed towards Tulagi if unable to make 15 knots. If consistent with the task, a destroyer screen would be provided. All ships were to be ready to tow or be towed. A ship becoming separated from the formation was not to rejoin until after requesting permission, giving bearing of approach in voice code. In the event of failure to rejoin during the engagement, ships would proceed to an agreed 0800 rendezvous.

In conclusion, Admiral Scott stressed the importance of maintaining formation to facilitate identification. All ships were to be alert for challenges, and to show night fighting lights with discretion.

PRELIMINARY MOVEMENTS

Task Force SUGAR departed from Espiritu Santo late in the afternoon of 7 October. Its approach was uneventful, marked only by target practice on 8 October and brief antiaircraft practice that night. A position north of Rennell Island, just outside the range of enemy air search, was assumed the next day. At 11227 on the 10th the Helena and Duncan joined the formation, which became complete with the arrival of the McCalla the next day.8 On both the 9th and 10th, approaches were made,

------------------

6 Voice radio.

7 All times in this Narrative are Zone minus 11.

8 The McCalla was with the Task Force when it sortied from Espiritu Santo on the 7th, but late that night was ordered by Admiral Scott to return to Espiritu Santo to collect mail, rejoining the formation at the earliest possible date.

4

as planned, to a 1600 position that permitted reaching the vicinity of Savo Island, at 20-25 knots, by 2300. However, air search revealed no suitable targets, and on both days the Task Force retired to the south of Rennell Island. Four planes from the force were flown to Tulagi on 10 October, to remain overnight and effect a rendezvous at 1600 on the 11th.

11 OCTOBER—EVENTS PRIOR TO ACTION

1347 Air search reports two enemy cruisers and six destroyers steaming towards Guadalcanal.

1400 Enemy air raid on Henderson Field delays return of Task Force SUGAR’s planes.

1600 Approach to Savo Islands begins.

1810 Air search again reports two enemy cruisers and six destroyers approaching Guadalcanal.

1815 Sunset; Condition of Readiness ONE is set.

2025 Course changed to 330 degrees T.

2115 Course changed to 000 degrees T.

2200 Cruisers launch I plane each.

2235 Battle disposition assumed on course 075 degrees T.

2300 Course changed to 050 degrees T.

2325 Helena’s SG radar contacts enemy vessel bearing 315 degrees T., distance 27,700 yards.

2326 Salt Lake City’s SC radar contacts three enemy vessels bearing 273 degrees T., distance 16,000 yards.

2335 Cruisers countermarch to 230 degrees T.

2342 Helena and Boise report radar contacts by TBS.

2346 Helena requests permission to open fire.

The morning of 11 October passed without incident and with no intimation that the day would be more eventful than the two which had preceded it.

At about 1345, however, search planes from Guadalcanal were reported by ComAirWing ONE as having sighted two enemy cruisers and six destroyers steaming at high speed on the accustomed Japanese route down “the slot” on course 120 degrees T. bearing 305 degrees T., at a point 210 miles from Guadalcanal. Estimating the situation, Admiral Scott concluded that to intercept the enemy, Task Force SUGAR should reach the Savo Island area about an hour before midnight. Meanwhile the force would proceed slowly to the 1600 position9 set for a rendezvous with the planes dis-

-----------------

9 Latitude 11 degrees 30’ S., longitude 161 degrees 45’ E.

5

patched to Tulagi the previous day. The OTC also doubtless hoped for further air search information about the enemy force.

However, the rendezvous and the more detailed information were delayed by a heavy Japanese air attack on Henderson Field during the afternoon of the 11th. Seventy-five planes attacked in four waves. Eight enemy bombers and four fighters were shot down, at a cost of two of our fighters. The Task Force’s planes at Tulagi were unable to take off as scheduled, and the enemy attack restricted the activities of long-range search planes at Guadalcanal. No other Japanese surface forces were sighted during the 11th, and Admiral Scott entered the engagement under the impression that only two enemy cruisers and six destroyers were opposed to him. In reality, the enemy force appears to have been considerably larger. If it had not been for the Japanese air attack, the additional ships might well have been sighted by our search planes.

Despite the failure of the cruiser planes to effect the agreed rendezvous, Task Force SUGAR at `600 departed at 29 knots from latitude 11 degrees 30’ S., longitude 161 degrees 45’ E., on course 320 degrees T. The cruisers were in column, the San Francisco leading, followed by the Boise, Salt Lake City, and Helena. The cruiser column was screened by the destroyers in a 2,500-yard semicircle ahead, with the McCalla and Buchanan to port, the Farenholt dead ahead, and the Duncan and Laffey to starboard. 10

At 1614 the cruisers each catapulted one plane to proceed to Tulagi, since it had been determined that each was to retain a single aircraft for search purposes on approach to the probable contact area.11 Between 1652 and 1709, however, the planes which had been flown to Tulagi the previous day finally appeared. It had been planned to send these aircraft back to Tulagi, but because of contaminated gasoline they were forced down in the immediate vicinity of our vessels. The Task Force immediately slowed to 10 knots, and the ships came right to render assistance. During the maneuver the San Francisco’s plane hit the ship’s side and was badly damaged. Admiral Scott was unwilling to lose the time required for salvage and ordered the Buchanan to recover the personnel and sink the plane. The Buchanan complied but did not regain her position in the formation until just after 2200, thus causing apprehension that she might not be available during the expected action.

-----------------

10Shortly before 1700, Admiral Scott informed the ships in the Task Force of his intention to attack that evening and mentioned the enemy’s strength as reported to him.

11In the Battle of Savo Island, the night of 8-9 August, planes had proved dangerously inflammable, and it was felt unwise to have any aboard during an action.

6

At 1810, ComAirWing ONE reported his search planes had again sighted two enemy cruisers and six destroyers on course 120 degrees T., bearing 310 degrees T., steaming at 20 knots some 110 miles from Guadalcanal. There was little doubt that it was the force originally reported. This second message reinforced the belief that no other enemy vessels were in the area.

Condition of Readiness ONE was set as the sun went down at 1815. The wind was 7 knots from 120 degrees T., the sea calm, with moderate swells. There was a 1,000-foot ceiling of broken cumulo-nimbus clouds. Dusk gradually gave way to a dark night, permitting surface visibility of 4,000 to 5,000 yards. The temperature was 81 degrees F.

Half an hour later, a navigational fix obtained aboard the Salt Lake City established her position as latitude 10 degrees 42’ S., longitude 160 degrees 14’ E. At 2025 the course was changed to 330 degrees T., and at 2145, when the Task Force passed through latitude 09 degrees 43’ S., longitude 159 degrees 26’ E., a further alteration was made to 000 degrees T. Speed was reduced to 25 knots.

From sunset onward Task Force SUGAR’s radars were as active as security considerations permitted. The San Francisco (F), lacked SG12 equipment. Admiral Scott had been informed that the frequency of the flagship’s SC13 radar was similar to that with which Japanese apparatus operated. Hoping to achieve surprise, he ordered the San Francisco’s SC not to be used during the evening. The flagship’s FC radar14 was in use, although on a limited search sector. The Salt Lake City, Boise, and Helena, possessed excellent SG equipment, all of which was actively employed as contact with the enemy became probable. The Boise’s SG was searching for enemy vessels continuously through 360 degrees. So, presumably, were the SG’s aboard the Salt Lake City and the Helena. The Salt Lake City’s SC was searching sector 180 degrees to 360 degrees R, and her FC was covering sector 225 degrees to 315 degrees R. The Boise’s FC had been assigned to sector 045 degrees to 135 degrees T. 15

About 2200, with the enemy likely to be encountered in another hour, Admiral Scott ordered one aircraft launched from each cruiser. Immedi-

------------------

12 Radar designed for installation in large vessels and used primarily for detection of surface craft.

13 A medium-range radar designed for detection of both surface ships and aircraft.

14 A fire-control radar primarily used for directing the fire of the main batteries; also used for short-range search.

15 Information concerning the radar operations of other ships in the Task Force is scanty. Admiral Scott indicated that he had assigned search sectors to several ships, but it is impossible to deduce what they were from the Action Reports and War Diaries.

7

ately after the Salt Lake City’s plane was catapulted, flares in the after cockpit inexplicably ignited, setting the aircraft ablaze. It crashed in flames 500 yards from the ship, burned fiercely for 3 minutes, and sank. The pilot and observer made Guadalcanal in the plane’s rubber boat. Task Force personnel were fearful that the fire had revealed the Force’s position to the enemy.

Admiral Scott’s order to the cruisers to launch their planes was never received by the Helena. But her commanding officer, Capt. Gilbert C. Hoover, was unwilling to incur the risk of keeping his plane aboard, and jettisoned it at 2214.

Just before 2230, as the Force neared the northwestern end of Guadalcanal, the course was changed to 075 degrees T., in order to round the tip of the island as previously planned. A few minutes later, with the enemy expected within the half hour, battle disposition was assumed. The destroyers Farenholt, Duncan, and Laffey formed column in the van, followed by the San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, and Helena in column, with the Buchanan and McCalla in column in the rear.

After effecting the change of course, the Salt Lake City made final battle preparations, jettisoning six 600-pound depth charges, and one depth bomb, all without pistols. As the ships passed the tip of Guadalcanal on the starboard hand, several lights were noted on the island. The Salt Lake City observed a white light, never identified, about 14,000 yards distant. The Helena saw a light on the starboard beam. Capt. Robert G. Tobin, commanding the destroyers from the Farenholt, sighted two blue lights on the beach at the northwest end of Guadalcanal. They had the appearance of range lights, so oriented that they might have been intended as aids to an approaching surface force. All indications were that such a force was expected.

Shortly before 2300, the pilot of the San Francisco’s plane reported sighting one large and two small vessels off the north beach of Guadalcanal, 16 miles from Savo Island. The message was not “well understood” on board the flagship, where a strong possibility was felt that the ships reported by the plane were friendly. Moreover, the night was very dark, and visibility from a plane was known to be extremely poor. Furthermore, even if taken at face value, the plane’s message seemingly referred to a force other than that which Admiral Scott believed to be approaching. With two cruisers and six destroyers expected off Savo momentarily, one large and two small vessels were merely an appetizer.

8

Ten minutes later Savo Island was uncomfortably close, and the course was changed to 050 degrees T., which left the island to starboard. The formation steamed on, while each passing minute increased the curiosity as to the whereabouts of the larger enemy force. The San Francisco’s FC radar was inadequate for long range search, but Admiral Scott had to rely on it for all information except that afforded the lookouts by the surface visibility of 4,000-5,000 yards. At 2230 the flagship’s plane reported that the one large and two small vessels previously reported were 16 miles east of Savo Island, about 1 mile off the Guadalcanal beach.

Meanwhile, unknown to the flagship, radar activity aboard the cruisers following her was becoming significant. At 2325, the Helena’s SG apparatus recorded an unmistakable surface vessel at bearing 315 degrees T., range 27,700 yards.16 A minute later, the Salt Lake City’s SG recorded three ships on bearing 273 degrees, 16,000 yards distant, proceeding at about 20 knots on course 10 degrees T. 17

Neither of these contacts was reported to Admiral Scott, who was becoming increasingly concerned lest, by steaming too far north, the enemy be given an opportunity to pass unnoticed between Savo and Guadalcanal. On the other hand, the two cruisers and six destroyers might have decided not to move on Guadalcanal that night. By reversing his course, the OTC would at least be able to engage the three ships reported by the San Francisco’s plane, and another sweep off the northern end of Guadalcanal would assure him of meeting the large force if in fact it did appear.

At 2332, according to the reports of the Salt Lake City, Farenholt and McCalla, 18 Admiral Scott transmitted the following TBS message to the Task Force: “This is CTF. Execute to follow: left to course 230.” Thirty seconds later he ordered, again over TBS: “From CTF: execute.” The four cruisers executed column left about, the San Francisco leading, followed by the Boise, Salt Lake City and Helena. The destroyers, however, delayed. Capt. Tobin ordered them “to slow as necessary to remain astern of the cruisers until it could be ascertained whether DD’s which had been in the rear were following cruisers in formation, or had turned to take

---------------------

16 See track chart, item No. 1.

17 See track chart, item No. 2. It is possible that the bearing was relative, not true; if relative, the enemy’s bearing would be approximately the same as recorded by the Helena.

18 The most accurate and complete record of the TBS messages which passed among the nine ships in the Task Force was kept by the McCalla. After the McCalla’s report, the Salt Lake City’s appears the most reliable. These two reports have been used as final authority for all points of disagreement.

9

new van positions.” When Capt. Tobin learned that the rear destroyers, the Buchanan and McCalla, had turned in the same water as the cruisers and were thus still in the rear, he ordered the former van destroyers, the Farenholt, Duncan and Laffey were then almost directly in the line of fire. 19

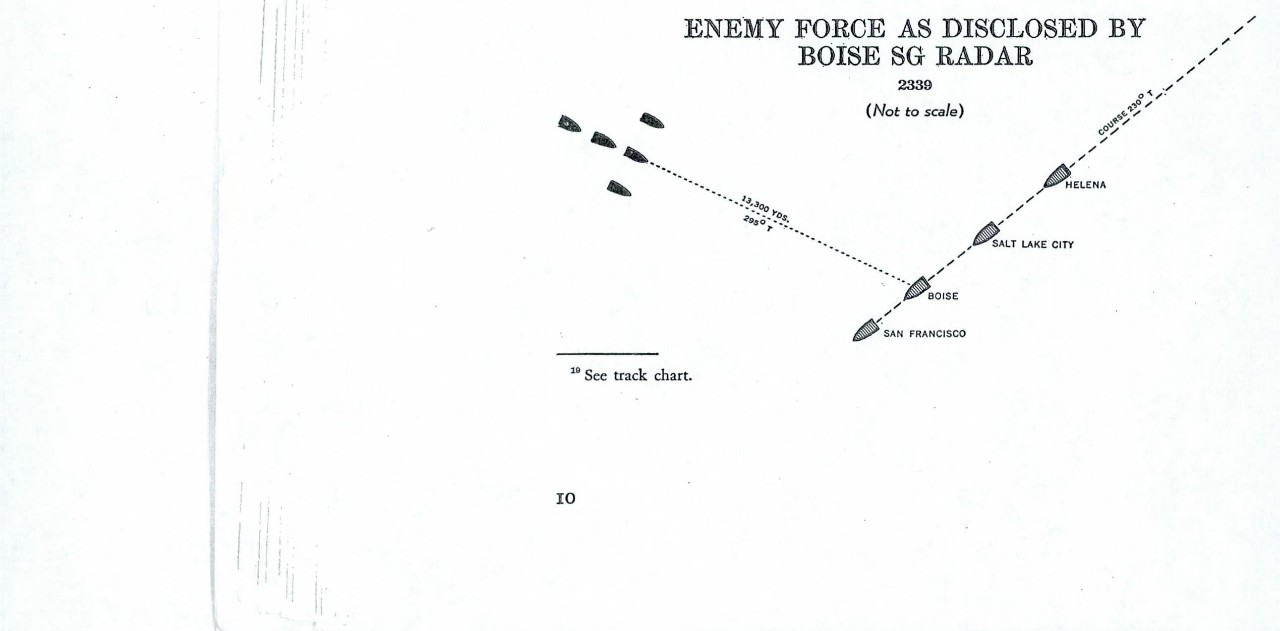

For a very few moments after turning south, Admiral Scott had no cause for concern other than uncertainty regarding the position of his destroyers. This period of calm was short-lived. Immediately after the turn, the Helena’s SG radar picked up at least five enemy ships at 18,500 yards on bearing 315 degrees T. At 2238, the Boise’s SG recorded a group of objects bearing 295 degrees T., about 14,000 yards distant.

Capt. Moran promptly directed the assistant navigator to make sure the objects were not land. A minute later Battery I received a report from Radar Plot locating five ships on bearing 065 degrees R. (295 degrees T.), only 13,300 yards away. “Action starboard,” “Set Condition Afirm,” and “Load” were immediately ordered by Capt. Moran. The enemy formation appeared thus on the Boise’s radar screen:

19See track chart.

Aboard the Boise, the location of Task Force SUGAR’s destroyers was known generally, but not precisely. Boise personnel were convinced there was no confusion at 2339 between the enemy’s ships and ours.

At about 2342, the Helena reported via TBS to Admiral Scott a surface radar contact, bearing 298 degrees T. The San Francisco’s FC radar was ordered trained out of its previously assigned sector to pick up this target, and the Helena’s report was transmitted to the task force.

When Capt. Tobin aboard the Fahrenholt –then abreast the cruiser column—received the message reporting the Helena’s radar contact, he realized the predicament of the three van destroyers. He ordered the speed of the destroyers reduced, and considered the possibility of tuning toward the cruisers in an attempt to take position astern of them. 20

Admiral Scott also perceived the threat to the destroyers, and queried Capt. Tobin as to whether the destroyer squadron was coming ahead. Capt. Tobin replied affirmatively, saying he was coming up on the starboard flank. At that moment, 2342, the Helena reported another surface contact, on a target 12,000 yards distant at 285 degrees T.

A minute later the Boise reported the radar contacts as pictured on her screen, but the message referred to the objects as “bogies” and two bearings went out over TBS: 065 degrees R. and 295 degrees T. Only the San Francisco received both bearings; other ships in the Task Force received only the relative bearing, which they interpreted as true. Even aboard the San Francisco, however, there was doubt whether by “bogies” the Bosie meant surface ships or aircraft, and whether, if surface ships, they were friendly or hostile. Lacking visualization of the scene afforded by an SG radar screen, Admiral Scott did not know what course the five destroyers had taken after the cruiser countermarch. He did not know whether all five destroyers, or only the three which had formerly been in the van, were coming up on the right flank of the cruisers. All he did know was that from three to five destroyers were somewhere to the rear and to starboard of the San Francisco. The possibility that these five destroyers were the “bogies” reported by the Boise was alarmingly real. At 2344 he again asked Capt. Tobin whether the destroyer squadron was taking station

----------------

20 Admiral William F. Halsey pointed out that “had the destroyers received radar contacts they would have passed on the opposite side from which the enemy were expected.”

11

ahead. An affirmative answer, received just as the Helena again reported 5 ships (at 10,000 yards on bearing 276 degrees T.)., was scarcely reassuring.

Only from the limited viewpoint of Admiral Scott aboard the San Francisco are the circumstances in which he ordered “open fire” and “cease fire,” understandable. Throughout the first phase of the battle, he could never know for sure that the cruisers following the San Francisco were not firing solely on our own destroyers.

THE ENGAGEMENT

On pages 24-26 is a chronological record of the experiences of all ships in the Task Force submitting Action Reports.21 Because the action was so intense and firing by all ships so rapid and simultaneous, it is impossible to relate their several stories without somewhat violating the sequence of time. It is hoped that occasional references to the chronological record and to the track chart will enable the reader to ascertain at a glance what was happening to other ships in the formation.

The first ship to go into action was the Helena, though only by a few seconds’ margin. At 2345 she requested permission over TBS to commence firing. The message was misinterpreted as a request for Admiral Scott to acknowledge the Helena’s last transmission reporting her radar contact on five ships. He answered her message by sending the word “Roger” over TBS. At 2346 both the Helena’s batteries opened on separate but unspecified targets.22

A few seconds later the Salt Lake City’s main battery opened on a ship 4,000 yards to starboard, believed to be a Natori class light cruiser, which was illuminated by starshells from the 5-inch battery. She was followed almost instantaneously by the Boise, whose main batteries concentrated on the Salt Lake City’s target, while her 5-inch battery directed its fire on a lighter vessel in the enemy van.23 Shortly thereafter, the Farenholt, from her position abreast of the cruiser column, fired on one of two heavy

-----------------

21 The Duncan was badly damaged during the first part of the action and sank about noon the following day, 12 October. See appendix, p. 20. The Laffey was sunk during the Battle of Guadalcanal, 13-15 November. There is no official record of the latter’s experience in the Battle of Cape Esperance.

22 Admiral Scott emphasized that he had instructed the cruisers to open fire without his prior permission.

23Less than a minute after the Boise opened fire, one of the antenna wires of the SG radar was jarred loose and wrapped itself around the antenna mast. The SG was useless thereafter, depriving the Boise’s fire directors of the visualization afforded by the SG screen.

12

cruisers clearly visible to starboard. The McCalla recorded sighting an apparently friendly destroyer 2,000 yards forward of her starboard beam. To the left of this destroyer (which was probably the Duncan), she saw an enemy cruiser and destroyer.

Aboard the San Francisco, the Helena’s unexpected opening of fire caused genuine alarm. The flagship’s FC radar, which had been trained out of its assigned search sector in an effort to locate the enemy vessels reported by the Helena, had by 2344 tracked a destroyer on bearing 300 degrees T., only 5,000 yards distant. A minute later this ship was visible through the heavy darkness, but whether friendly or hostile was not known. It was thought the destroyer might be the Farenholt, Duncan or Laffey. When the cruisers in the San Francisco’s rear had been firing for a few moments, the flagship herself opened fire with both her batteries on an unidentified enemy ship 4,600 yards to starboard. After a few salvos had been fired, the target ship and another close to it were burning, one severely. Fire was shifted to an Amagiri class destroyer approaching from the starboard beam, and it was soon heavily damaged.

Just after the San Francisco joined the other cruisers in continuous fire to starboard, Admiral Scott ordered “Cease firing” over TBS.24 His information regarding the location of the former van destroyers was still confined to the fact that they were somewhere on the starboard flank of the cruiser column, striving to regain their van position.

At 2347 the OTC asked Capt. Tobin over TBS whether the destroyers had been fired upon. He replied that none of his ships had as yet been fired on, and that he did not know on whom the cruisers were firing. A minute later, the Farenholt was hit twice in the rigging, and Capt. Tobin reported the hits to the flagship. The destroyer’s peril was most grave, but Capt. Tobin had no alternative to steaming ahead and reaching the van position as soon as possible. A turn to the left would have thrown the Farenholt into the middle of the cruiser column, and a turn to the right would have thrown her against the enemy.

Following the Farenholt was the Duncan. She appears quite early to have seen the opportunity for a torpedo salvo at an enemy heavy cruiser, to have weighed the risk of fire from our cruisers against the advantage of torpedoing the Japanese ship, and deliberately to have changed her

--------------

24 The McCalla’s log times this TBS message at 2346, the Salt Lake City’s at 2347; the latter time seems more likely because, during the 60 seconds from 2346 to 2347, the TBS was heavily occupied with other messages, particularly the “Roger” colloquy between the flagship and the Helena.

13

course to starboard, toward the enemy. She apparently scored two torpedo hits on the cruiser, and was then so severely damaged by shells from both Japanese and United States vessels that she retired from the action, blazing furiously and drifting northeastward toward Savo Island.25

Within a few minutes after Task Force SUGAR went into action, at least three enemy ships were in flames. The Salt Lake City checked her fire when received Admiral Scott’s order and did not resume for several minutes. The Helena and Boise recorded that their three targets sank at about 2350. The ship reported sunk by the Helena was never identified. The Boise stated that several of her officers identified her main battery target as a Nachi class heavy cruiser. The vessel burned furiously before sinking and was identified in the light of the flames.26 The Boise’s 5-inch battery target, which sank at about the same time, was a destroyer. A minute later, the destroyer engaged by the San Francisco sank. It had closed in to about 1,400, and could clearly be distinguished from our own destroyers. In less than 5 minutes, Task Force SUGAR had apparently destroyed one heavy cruiser, one unidentified ship, and three destroyers, without the enemy having fired a single shell.

By 2351, more certain of the location of the enemy vessels, Admiral Scott ordered the Task Force to commence firing. The Boise concentrated both her batteries on a destroyer in the vicinity of her 5-inch battery’s first target. The enemy ship quickly exploded and disappeared from the radar screens. Both the Helena’s batteries were trained on the 5-inch batteries’ first target, then 5,000 yards distant and to the right of two other burning ships. After several minutes observers saw it roll over and sink, having identified it as a Kako class heavy cruiser. The Salt Lake City trained her guns on a heavy cruiser and resumed fire, but checked after noting several hits.

Between 2353 and 2358, when almost abreast of the San Francisco, the Farenholt received wat appeared to be two 6-inch hits on her port side. Shortly thereafter she succeeded in crossing ahead of the flagship, but her hard-won position in the van could not be maintained. She was badly damaged, and fell out to port on the disengaged flank, losing

----------------

25 The recovery of the Duncan’s personnel, her attempted salvage, and final sinking are discussed in the appendix. The above information regarding her part in the battle has been gathered from various sources and is partly conjecture. What is relatively certain is that the Duncan’s brief but violent role was played during the early minutes of the action.

26 This was the same target fired upon by the Salt Lake City, which identified it as a light cruiser.

14

contact with the formation. She did not rejoin it until the next day, at Espiritu Santo.

The Buchanan, meanwhile, had apparently fallen in behind the cruiser column. After receiving Admiral Scott’s “Commence Firing” order, she observed three destroyers on the starboard beam, all on a course parallel to that of the Task Force. Probably this was the same Kako on which the Helena was firing. The Buchanan fired her main and torpedo batteries at the cruiser and 3 minutes later saw two explosions, presumably caused by torpedo hits. The cruiser was seen to break n two and sink, whereupon the Buchanan shifted fire to one of the destroyers. When it was observed sinking, she turned her guns on a target that was either a transport or a second-line cruiser. It was soon in flames and retired to the northwest.

Until 2353, no enemy gun or torpedo fire had been encountered. The Japanese were evidently completely surprised, and the impact of our accurate fire, concentrated into a period of barely 7 minutes, apparently prevented them from training their guns on our ships. A factor which doubtless contributed to the enemy’s delay was that none of our ships had thus far used searchlights. Firing had commenced and continued either in full radar control, or, aboard the cruisers, with the 5-inch batteries illuminating targets which had initially been located by radar.

At 2353, with the Helena engaging what appeared to be a light cruiser, the McCalla firing alternately on a heavy cruiser and a destroyer, the Salt Lake City momentarily silent, and the San Francisco attempting to identify a destroyer approaching to starboard and flashing unrecognizable signals, the Boise fired with both batteries, using searchlights for illumination, on an enemy cruiser. The cruiser promptly retaliated, and a minute later the Boise received an 8-inch hit which started large fires in the area of the captain’s cabin. Two or three enemy 5 1/2-inch shells followed in rapid succession before the Boise’s target commenced burning brightly. In a minute it was reported to have sunk. Capt. Moran checked fire and instituted damage control measures.

The Salt Lake City’s main battery meanwhile had taken under fire, at a range of 7,000 yards, an enemy ship tentatively identified as an auxiliary. The target apparently sank, and the Salt Lake City checked fire, resuming with both batteries on a destroyer illuminated by searchlight. This destroyer disappeared after one salvo had been fired.

Between 2353 and 2358 the course of Task Force SUGAR was changed

15

from 2300 T. to 3000 T. About midnight, Admiral Scott ordered “Cease Firing” in order to rectify his formation. He stated his course and ordered all ships to identify themselves by blinker lights. A lull in the fighting did occur, largely because most of the targets which had been engaged were no longer visible.

The lull was brief. Between 0001 and 0005 the Salt Lake City fired on three burning enemy ships, increasing the fires on each before shifting her guns to the next. At 0005 the Helena resumed firing on a destroyer which was soon in flames. Ten minutes later it exploded and disappeared both from the radar screens and from sight. At 0006 the San Francisco observed at least four enemy ships on fire and trained both batteries on them in succession.

For the first 8 minutes after midnight the Boise was busy with her own fires. At 0006 a torpedo wake was observed to starboard. She came right with hard rudder and the torpedo passed about 50 yards astern. By 0009 her fires were substantially extinguished, and she reentered the battle only slightly damaged. Using searchlights to illuminate the target, both batteries reopened on an unidentified ship to starboard, which promptly returned her fire. Simultaneously, she was engaged by a heavy cruiser separated from the previous enemy area and believed by Boise personnel to have been one of another enemy group hitherto not involved in the action. This latter cruiser fired “beautifully” at the Boise, hitting her repeatedly with 8-inch salvos which virtually destroyed her forward turrets and caused large personnel casualties and material damage. A succession of 5-inch, 6-inch, and 8-inch shells poured on the Boise for the better part of 4 minutes. She was soon blazing so fiercely that her sister ships feared she was lost. But she continued to mete out terrific punishment and had the satisfaction of seeing her destroyer target explode and sink. Then, while firing at the cruiser with every gun which could shoot, she began evasive action. But soon none of her heavy guns could bear, and at 0013, wrapped in flames, she fell out of the formation and retired to the southwest.

Though the heavy cruiser which had so greviously damaged the Boise enjoyed an initial advantage in being able to fire unopposed, it was not long before she was being heavily battered by the Task Force’s other cruisers. The Salt Lake City was engaging a light cruiser when she saw the Boise’s plight. Fire was immediately checked, in order to obtain a solution on the heavier and deadlier target. The Salt Lake City had to

16

maneuver frequently to avoid the Boise, which was changing course continually in efforts to escape her assailant’s fire. While thus maneuvering the Salt Lake City received an 8-inch hit forward and to starboard. At 0014 her guns were trained on the enemy, and for a minute she rained 8-inch shells on the heavy cruiser. The San Francisco, meanwhile, had also brought this accurately shooting vessel under her 8-inch gunfire, and it is probable that other ships in the Task Force were also firing on her.

At this juncture the Salt Lake City received another 8-inch hit to starboard, causing minor damage and a few casualties to personnel. But the enemy cruiser could not withstand the concentrated fire of the Task Force, and at 0016 she was seen to sink.

The action was now virtually concluded, although the McCalla temporarily engaged a destroyer at 0016, and the San Francisco fired a few salvos at a three-stack cruiser at 0017. The enemy destroyer retired in flames, and the cruiser disappeared from the radar screen with no indication of the results of the flagship’s salvos. The course had been changed to the right to 330 degrees at 0016 in order to close the enemy, but after these last few minutes of desultory firing, Admiral Scott decided to retire. An eloquent silence prevailed over the area once filled with enemy ships.

Our own formation was “somewhat broken,”27 and it seemed best to rectify it should any additional enemy ships appear. Course was changed at 0027 to 220 degrees T. Admiral Scott tried unsuccessfully to establish communication with Capt. Tobin to have him detail a destroyer to stand by the Boise. Neither Capt. Tobin in the Farenholt nor Capt. Moran in the Boise could be reached. Accordingly, the McCalla was designated to remain in the area to render whatever assistance appeared necessary. The remainder of the Task Force then retired on course 2050 T.

RETIREMENT

At 0050 the Salt Lake City “enlivened the occasion” by firing two star shells to illuminate the San Francisco. The flagship was then well ahead of the formation and her friendly character was doubted. In 10 minutes, however, the two cruisers identified each other, and the Salt Lake City fell in behind the flagship, reporting her maximum speed as 22 knots, an estimate she later raised to 25. Admiral Scott ordered all destroyers

----------------

27 See track chart.

17

to close him, but could obtain no acknowledgment from the Farenholt or the Duncan.

Two hours later the Boise was encountered for the first time since she had fallen out of the formation. She was heavily damaged, and had lost three officers and 104 enlisted men, but because of intensive damage control measures her fires were out and she was able to make 20 knots, the speed Admiral Scott accordingly set for the Task Force. Meanwhile, the Helena had joined, and the victorious formation steamed southwards, minus only the Farenholt and the Duncan.

Admiral Scott’s major concern was to get out of range of enemy land-based aircraft by daylight. He sent a radio report of the battle to COMSOPAC. He also requested air coverage, which arrived soon after day broke. Later in the morning, a message was received from the Farenholt, stating that she was 50 miles to the rear. She reported that she had been holed twice near the water line but that she was seaworthy.

It was still necessary to pick up the Task Force’s cruiser planes which had been flown to Guadalcanal. The Helena was detached for the purpose, and three destroyers, the Lansdowne, Aaron Ward and Lardner, were dispatched from Espiritu Santo to screen her. The Aaron Ward was later directed to escort the Farenholt.

At 1530 on 13 October, Task Force SUGAR steamed into Espiritu Santo, followed two hours later by the Farenholt. The Helena, Lansdowne and McCalla arrived the next morning, with the Duncan’s survivors aboard the McCalla (nine officers and 186 men). Also aboard were 3 Japanese seamen who had been picked up from the water in the vicinity of the Duncan.28

Total casualties in the Task Force were about 175 killed and an unspecified number wounded. The Action Reports which form the basis of this Narrative indicate about 15 sinkings of enemy vessels. As in all night actions, observation was difficult and many duplications resulted. A preliminary effort to eliminate these was made at a conference at Espiritu Santo, attended by all the ships’ commanding officers, where the enemy losses were estimated as: one heavy cruiser of the Nachi class, one of the Kako class, and one of the Atago class; one possible light cruiser

---------------

28 The recovery of the Duncan’s survivors from the shark-infested waters off Savo Island and the seizure of the Japanese prisoners are treated separately in the appendix, p. 20.

18

of the Sendai class; four destroyers, one of the Hibiki class; one other possible, type unknown.

This estimate was later revised by Admiral Nimitz as follows:

Two heavy cruisers, one of which was the Furutaka.

One light cruiser.

One auxiliary, possibly a transport.

Five destroyers, one of which was the Shirakumo.

(b) DAMAGED:

One heavy cruiser, the Aoba, badly damaged.

Other destroyers.

It seemed apparent, from the losses inflicted, that the Japanese force was larger than had been reported to Admiral Scott on 11 October. The ships sighted by search aircraft that day totaled only two cruisers and six destroyers. But it will be recalled that an air attack was mad on Henderson Field the afternoon of the 11th, possibly preventing detection of other units which were either part of the force sighted or comprised a separate group moving towards Savo Island so as to effect a junction with the force reported by search planes. There is no way of assessing the exact size of the Japanese forces engaged. Admiral Scott estimated that three heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and six destroyers were involved.

CONCLUSIONS

The major factor in the victory, as stated by Admirals Nimitz and Scott, was surprise. Our ships fired on the enemy with devastating effect for 7 minutes before his guns replied. Reasons for his delay in firing are difficult to ascertain. The most plausible are two: first, that the Japanese lacked radar as effective as that aboard the Salt Lake City, Boise, and Helena; second, that the enemy ships engaged comprised two forces.30 If tow units were in fact involved, it is probable that the Japanese were, at

--------------------

29 Later information made the following Japanese losses seem certain: sunk 1 CA (Furutaka), 2 DD (Fubuki and Natsugumo).

30It is also possible that the Japanese vessels believed that they were being fired upon by the one large and two small ships reported by the San Francisco’s plane before the action started. These three vessels were later seen, at 0230 on 12 October, by Lt. (jg) R. C. Bartlett, the pilot of the Boise plane which had made a forced water landing midway between Guadalcanal and Florida Islands. Three Japanese warships, one of which was the light cruiser Itukusima, passed within 300 yards of him.

19

the outset, uncertain regarding who was firing on them, and hesitated to retaliate for fear of hitting their own ships31

But surprise alone would not have produced so one-sided a victory under the confused conditions prevailing when the action commenced. The cool judgment exercised by individual captains in handling their vessels, combined with gunnery as effective as could ever be expected, enable our Task Force to wrest a decisive victory from an inherently dangerous opening situation.

APPENDIX

Abandonment of the “Duncan” and Rescue of Her Survivors by the “McCalla”

While making two torpedo hits on a Japanese cruiser from a position between our cruiser column and the enemy force, the Duncan was simultaneously hit by four or more shells, including several from our cruiser column. Her No. 1 fireroom had already been damaged by a shell hit, but the crew had remained at their stations in order to secure the forward boilers. This devotion to duty cost them their lives, for when the fireroom was hit again, all men in it were killed. Other shells burst and killed all personnel in the charthouse and the main radio room. Another hit near the charthouse killed four men on the wings of the bridge. One of these men was standing next to the commanding officer, Lt. Comdr. Ennis W. Taylor. Uncontrollable fires quickly broke out near the No. 1 fireroom and the main radio.

No. 2 gun mount was a mass of flames, with fire and explosions from the handling room cutting off access to the forecastle. Everything from the bridge level up was isolated by fires roaring just below. The charthouse and after end of the navigating bridge were wrecked. The forward and after parts of the ship were two distinct units, separated by flames from the fire in No. 1 fireroom. All communications from the pilothouse to other parts of the ship were dead. The gyro-repeater was out. There was no answer from signals over the engine room annunciator. Bridge steering control was lost, and with her rudder jammed left the Duncan was carried clear of the line of fire and away from the battle area. She was still making 15 knots.

---------------------

31 Boise officers, interviewed while she was undergoing repairs in Philadelphia, strongly inclined toward this second theory, particularly because of their conviction that the ships which fired so effectively on their vessel during the second phase of the action were not part of the force first engaged.

20

The director crew and the uninjured personnel on the director platform lowered the wounded to the starboard wing of the bridge. But the bridge was isolated from all parts of the ship by increasingly serious fires raging beneath, forward and aft. Accordingly, Lt. Comdr. Taylor ordered the personnel gathered on the bridge to abandon ship. Efforts were made to reach the life net just beneath the port wing of the bridge, but the smoke was too thick and the flames too fierce. Escape from the bridge level was possible only by dropping into the water over the starboard wing. All bridge personnel left the ship in this manner.

During their escape and for many minutes afterward, Lt. Comdr. Taylor strove unsuccessfully to signal the crew of gun No. 1 and the survivors from gun No. 2, who were gathered in the eyes of the ship, isolated by fires which had spread to the magazines under gun No. 2. After a final effort to communicate with men in the after part of the ship, and when an inspection of the bridge level showed that the port wing was on fire and that all living personnel had got clear, Lt. Comdr. Taylor jumped from the starboard bridge shield at about 0100, a half hour after giving the order to abandon the bridge.

The remaining personnel forward and aft made persistent efforts, despite continually exploding ammunition and intense fires, to bring the flames under control with fire and bilge pumps and the handy-billy. Both bilge pump and handy-billed failed. At about 0200, with the flames increasing in intensity and ammunition exploding ever more violently, Lieut. Herbert R. Kabat ordered all personnel to abandon ship.

The McCalla, meanwhile, had followed the course of the San Francisco during the battle with little difficulty. When the engagement was concluded, at about 0020, she was in her station astern of the flagship.

At 0055 she was ordered by Admiral Scott to locate the Boise, which had last been reported 12 miles from Savo Island on bearing 2950 T. The McCalla searched in vain for the damaged cruiser, using FD radar, on various courses and speeds. The only vessel sighted was gutted with fire, drifting so close to Savo Island that it was thought she might be on the opposite side of the island from which the action had been fought. As the McCalla neared the flames, several explosions were heard, and it seemed the ship was aground. The McCalla approached cautiously because the large fires made it impossible to determine the ship’s characteristics. At 0220 her fires had diminished, and she was illuminated by searchlight frm an approximate range of 2,500 yards. She was

21

clearly not the Boise. Shortly, a lookout detected the numbers 485, and she was identified as the Duncan.

At 0300, the McCalla lowered a boat and despatched a salvage party under Lt. Comdr. Floyd B. T. Myhre with instructions to take no unnecessary chances, approach with caution, and fire a red Very star if immediate assistance was required. Lt. Comdr. Myhre was told the McCalla would remain in the vicinity for about half an hour, and then continue to search for the Boise, returning to the Duncan only if the Very star signal was observed.

The salvage party went aboard but found no signs of life. Many fires were still burning, which Lt. Comdr. Myhre gradually brought under control. After a brief examination of all parts of the destroyer, he decided there was a hope of salvaging her. He and his party worked steadily for several hours jettisoning equipment which was irretrievably damaged, and trying to restore power.

Meanwhile the McCalla searched north and west of Savo for the Boise, unaware that she had by that time resumed station in the Task Force. Around 0600, the Duncan was again encountered. She was still smoldering forward, but all large fires had burned themselves out. As the McCalla closed, Lt. Comdr. Myhre reported that she had been abandoned but could be salvaged, and asked Lt. Comdr. Cooper in the McCalla to send a repair party, stating that the Duncan, though deep in the water aft, could be towed by the stern.

Lt. Comdr. Cooper decided first to recover the Duncan’s personnel. Many survivors could be observed in the water as daylight approached, clinging to life rafts and debris scattered in a roughly rectangular area to the eastward of Savo Island, about 8 miles north and south and 2 miles west. The largest group rescued included 31 men lying on 3 life rafts which had been lashed together. Rescue operations continued from 0630, when the first survivors were taken aboard, until 1209. The McCalla was aided by planes and landing boats sent to the area by the Commanding General on Guadalcanal. In all, 9 officers and 186 enlisted men were rescued, the great majority being taken aboard the McCalla.

Most of the Duncan’s personnel were picked up without incident. But while one man was being picked up, another, 200 yards away, was seen being viciously attacked by a large shark. Three members of the McCalla’s crew were armed with rifles. Their many accurate shots kept the shark at

22

a distance until a boat could be lowered and the victim, Lieut. Kabat, taken aboard. Several other survivors were closely investigated by sharks, but only 3 were attacked. Fortunately, no lives were lost as a result.

When the Duncan’s survivors had been taken aboard the McCalla or sent to Guadalcanal, the McCalla endeavored to tow the Duncan. But all efforts were unavailing, and she sank shortly after noon.

At 1430, a large number of men were sighed from the McCalla, floating in the sea near the scene of the previous night’s action. Investigation revealed that these were Japanese seamen, survivors of the several enemy ships on the ocean floor beneath. The McCalla tried to pick up several of them by heaving them lines. None would catch hold, however. The McCalla lowered a boat and captured 3 survivors, not trying to seize more because she was already overcrowded and had very limited space in which to confine them. A message was sent to the Commanding General at Guadalcanal, with the request that he rescue those remaining in the sea. Two destroyers were dispatched from another task group in the area. Between them, these ships picked up 113 Japanese prisoners. How many were eaten by sharks is unknown.

23

Battle of Santa Cruz Islands

26 October 1942

INTRODUCTION

ENEMY naval losses in the Battle of Cape Esperance on the night of 11 October appeared to have been the heaviest since Midway. Indeed, it might reasonably have been anticipated that the Japanese High Command would pause to resurvey the situation in the South Pacific before committing itself to further attempts to recapture Guadalcanal.

As it turned out, the lull lasted only 48 hours, during which some 6,000 United States Army troops were landed without opposition. From that time until 26 October, enemy land, air, and sea power made strenuous efforts to cut our communications and to put Henderson Field out of commission so that contemplated full-scale amphibious operations would not face land-based air opposition. In the final stage of neutralization, the Japanese expected their ground troops to capture the field, making it available as a staging point for the carrier planes which would support the final mopping up of our forces.

The initial phase of this plan enjoyed a measure of success. The drive to take Henderson Field, however, ended in bloody failure. With it, as a sort of by-product, came the carrier action known as the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands.

First evidence that the enemy’s determination had not been shaken came shortly before midnight on 13 October, when a Japanese force of two battleships, one light cruiser, and eight destroyers began a furious bombardment of Henderson Field which lasted an hour and 20 minutes. Casualties to personnel were light, but most of our planes were destroyed. The next night, cruisers and destroyers again shelled the field, and in the morning only one dive bomber was able to take to the air to oppose a Japanese landing being made from six transports west of Kokumbona. Other dive bombers were flown in from Espiritu Santo, and with the help of Army B-17’s they destroyed at least three of the transports, set

29

others afire, and damaged a heavy cruiser which, with two light cruisers and four destroyers, was acting as screen. Nevertheless, considerable equipment and about 10,000 enemy troops had been put ashore.1Another bombardment took place that night, and air raids occurred almost daily. Under cover of darkness, smaller hostile units and additional supplies were debarked, and the strengthened Japanese ground forces began intensive probings of our positions along the Matanikau River, where we had established our western line in anticipation of a general enemy offensive.

Simultaneously with the beginning of Japanese pressure on Guadalcanal, large numbers of merchant and combat vessels assembled in the Upper Solomons-New Britain area. At the same time troops and aircraft began a steady procession from the Netherlands Indies, the Philippines, and other strongholds toward the vicinity of the impending conflict.

A growing number of enemy submarines began to harry our Espiritu Santo-Guadalcanal supply line. On 20 October, one of them torpedoed the heavy cruiser Chester, inflicting extensive damage. On the 15th, planes from the converted carriers Hitaka and Hayataka attacked a convoy en route to Guadalcanal, sinking the destroyer Meredith.

Estimating the situation as the third week of October opened, CINCPAC concluded that the enemy intended to launch simultaneous land and sea attacks, sending in carrier planes to support his gains. Available carriers and battleships were expected to attempt to contain or destroy any surface forces which we might send to intervene. It was anticipated that 23 October would be the Japanese “zero day.” As it developed, “zero day” was apparently postponed repeatedly because the Japanese were unable to maintain a breach in the Marine defenses and thus did not reach their Henderson Field objective.

FORCES INVOLVED

Before the action there was no way of accurately gauging the naval strength which the enemy planned to unleash when “zero day” arrived. The event proved that his forces were more than impressive, comprising four carriers, four battleships, and an armada of lesser war vessels, in addition to transports and other auxiliaries. The carriers were the Shokaku, Zuikaku, Hayataka, and Zuiho. A fifth, the Hitaka, was

-----------------

1 Estimated as 16,000 by General Vandegrift.

30

available in the Shortlands area until 21 October, when damage necessitated her departure for Truk.

Our own forces in the South Pacific area were weak in comparison. The Enterprise had been damaged in the Battle of the eastern Solomons,2 23-25 August, and was undergoing repairs at Pearl Harbor. The Wasp had missed that engagement, but while supporting Guadalcanal on 15 September she was torpedoed and sunk by an enemy submarine. On the same day the new battleship North Carolina was torpedoed and forced to put in for repairs. The Saratoga, likewise, was out of action because of a torpedo hit received on 31 August. 3

On the credit side of the picture was a task force built around the aircraft carrier Hornet and including the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola, the antiaircraft light cruisers Juneau and San Diego, and a number of destroyers. Our only battleship in the South Pacific was the Washington, which had supported the movement of the Army convoy into Guadalcanal on 13 October.

With the exception of several destroyers engaged in protecting the supply ships running between Espiritu Santo and Guadalcanal, COMSOPAC had no other combat units available except the surviving ships of Task Force SUGAR, which the Battle of Cape Esperance had temporarily deprived of the Salt Lake City, Boise, and Farenholt, in addition to the Duncan, which was sunk.

One carrier, one battleship, and their attendant complement of cruisers and destroyers could hardly be expected to withstand the weight of the forces known to be available to the Japanese. Therefore, as the power of the enemy offensive became more and more evident, COMSOPAC began marshalling all possible resources. United States submarines were concentrated in the Bismarck Islands. Air strength available to COMAIRSOPAC at Espiritu Santo was augmented to include about 85 patrol planes and heavy land-based bombers. By 26 October, 23 fighters, 16 dive bombers, and one torpedo plane were ready for action at Guadalcanal. Four PT boats moved into Tulagi Harbor at dawn on 25 October. Aircraft of the Southwest Pacific Command intensified their attacks on Rabaul and on airfields in the Bismarcks. On the 3 nights before the 26th, they reported hits on about 10 ships in Rabaul Harbor, including a cruiser and a destroyer.

----------------

2 See Combat Narrative, “The Battle of the Eastern Solomons.”

3 See Combat Narrative, “Miscellaneous Actions in the South Pacific.”

31

Our most urgent need, however, was for fleet surface and air units with which to counter the enemy carrier and battleship forces. At Pearl Harbor was Task Force KING, under Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, built around the Enterprise and the new battleship South Dakota. Repairs to the damaged carrier were rushed to completion, and on 16 October she departed with her escort, including the South Dakota, under orders to proceed at high speed to the South Pacific and rendezvous with the Hornet group, commanded by Rear Admiral George D. Murray. Thereafter she was to operate under the command of Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Commander South Pacific. COMSOPAC, meanwhile, had decided to use the Washington force, reinforced by the remaining effective ships of Task Force SUGAR, as a striking unit to interrupt Japanese surface forces supplying Guadalcanal. About midnight on 25 October, these ships made a sweep around Savo Island. They encountered no enemy vessels and retired southward before daylight, under the sporadic observation of Japanese planes.

At 12454 on 24 October the Enterprise and Hornet Task Forces joined in latitude 14 degrees 07’ S., longitude 171 degrees 37’ E., northeast of the New Hebrides Islands. Admiral Kinkaid, acting under orders from COMSOPAC, assumed command of both groups, which will hereafter be identified as Task Force KING. The following ships were present:

Enterprise Group

I carrier:

Enterprise (F, Rear Admiral Kinkaid)—Capt. Osborne B. Hardison.

I battleship:

South Dakota—Capt. Thomas L. Gatch.

I heavy cruiser:

Portland (Capt. Mahlon S. Tisdale, Commander Cruisers)—Capt. Laurance T. DuBose.

I antiaircraft light cruiser:

San Juan—Capt. James E. Maher.

8 destroyers:

Porter (Capt. Charles P. Cecil, Commander Destroyers)—Lt. Comdr. David G. Roberts.

Mahan—Lt. Comdr. Rodger W. Simpson.

Cushing—Lt. Comdr. Christopher Noble.

Preston—Lt. Comdr. Max C. Stormes.

Smith—Lt. Comdr. Hunter Wood, Jr.

---------------

4All times in this Narrative are Zone minus 12.

32

Maury—Lt. Comdr. Gelzer L. Sims.

Conyngham—Lt. Comdr. Henry C. Daniel.

Shaw—Lt. Comdr. W. Glenn Jones.

Hornet Group

I carrier:

Hornet (F, Rear Admiral Murray)—Capt. Charles P. Mason.

2 heavy cruisers:

Northampton (F, Rear Admiral Howard H. Good, Commander Cruisers)—Capt. Willard A. Kitts, III.

Pensacola—Capt. Frank L. Lowe.

2 antiaircraft light cruisers:

San Diego—Capt. Benjamin F. Perry

Juneau—Capt. Lyman K. Swenson.

6 destroyers:

Morris (Comdr. Arnold E. True, Commander Destroyers)—Lt. Comdr. Randolph B. Boyer.

Anderson—Lt. Comdr. Richard A. Guthrie.

Hughes—Lt. Comdr. Donald J. Ramsey.

Mustin—Lt. Comdr. Wallis F. Petersen.

Russell—Lt. Comdr. Glenn R. Hartwig.

Barton—Lt. Comdr. Douglas H. Fox.

THE APPROACH

COMSOPAC ordered Task Force KING to skirt the northern shores of the Santa Cruz Islands, move southwestward to a point east of San Cristobal Island, the southernmost of the Solomon chain, and be prepared to intercept the Japanese as they approached Guadalcanal. The Hornet was instructed to operate about 5 miles to the southeast of the Enterprise force, on a bearing approximately normal to the wind line. Course was set to leave Fataka Island and Strathmore Shoal to port. The Task Force was steaming at 23 knots.

At 0400 on 25 October, in latitude 100 50’ S., longitude 1710 50’ E. (east of the Santa Cruz Islands), course was altered to the northwest. The Enterprise assumed duty carrier status and conducted all inner air patrols, combat air patrols, and searches. The Hornet maintained a striking group on the alert.

The morning search to a distance of 200 miles in sector 2900-0800 T. (see chart, p. 28) was accomplished with negative results. However, about 1120 a shore-based patrol plane contacted an enemy force of two battleships, four heavy cruisers, and seven destroyers. And at 1250 the

33

seaplane tender Curtiss relayed a report from another patrol plane that two Japanese carriers and supporting vessels had been sighted in latitude 080 51’ S., longitude 1640 30’ E. (about 360 miles from Task Force KING), course 145, speed 25. The location of the battleship-cruiser group was not clear (actually it was operating 60-80 miles south of the carriers). In order to gain more complete information on the enemy’s whereabouts and to strike the carriers if they continued their approach, Admiral Kinkaid decided to launch search and attack groups from the Enterprise, keeping the Hornet aircraft in reserve pending further reports.

At 1430 the Enterprise sent out 12 scouts in pairs for a mile search of sector 2800-0100 T. About an hour later she launched an attack group of 11 fighters, 12 scouts and 6 torpedo planes, with her Group Commander, to follow up the search. These aircraft were ordered to proceed out on the median line of the search to 150 miles, and to return if no enemy ships were encountered.