The Navy Department Library

Battle of Guadalcanal

11-15 November, 1942

Battle of Guadalcanal

11-15 November, 1942

Including the Enemy Air Attacks of 11 and

12 November; the Cruiser Night Action of 12-

13 November; the Air Operations of 13, 14,

and 15 November; and the Battleship Night

Action of 14-15 November

Confidential[declassified]

OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE

U.S. NAVY

[1943]

Combat Narratives were written to fill a temporary requirement before the appearance of official and semiofficial complete histories. Due to hastily gathered and oftentimes incomplete information there are certain inaccuracies.

Combat Narratives

Solomon Islands Campaign: VI

Battle of Guadalcanal

11-15 November 1942

Confidential

Publications Branch

Office of Naval Intelligence - United States Navy

1944

CONTENTS

| Page | |||

| Foreword | iii | ||

| Part I - Enemy air attacks of 11-12 November and Cruiser Night Action of 12-13 November | 1 | ||

| Introduction | 1 | ||

| Approach to Guadalcanal - the plan | 6 | ||

| First phase - enemy air attacks of 11-12 November | 9 | ||

| Second phase - Cruiser Night Action of 12-13 November | 15 | ||

| Part II - Air attacks of the 13th and 14th | 37 | ||

| Preliminary - the Enterprise departs from Noumea | 37 | ||

| Action on Friday, the 13th - fate of the Hiyei | 39 | ||

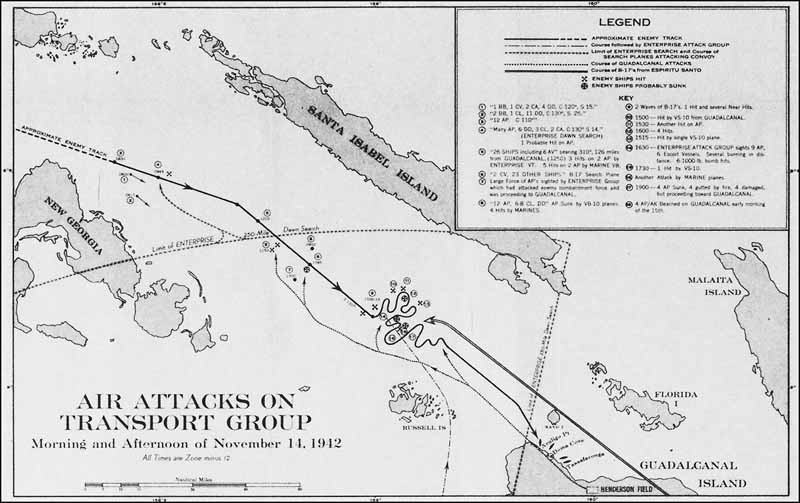

| Enemy transport fleet shattered | 41 | ||

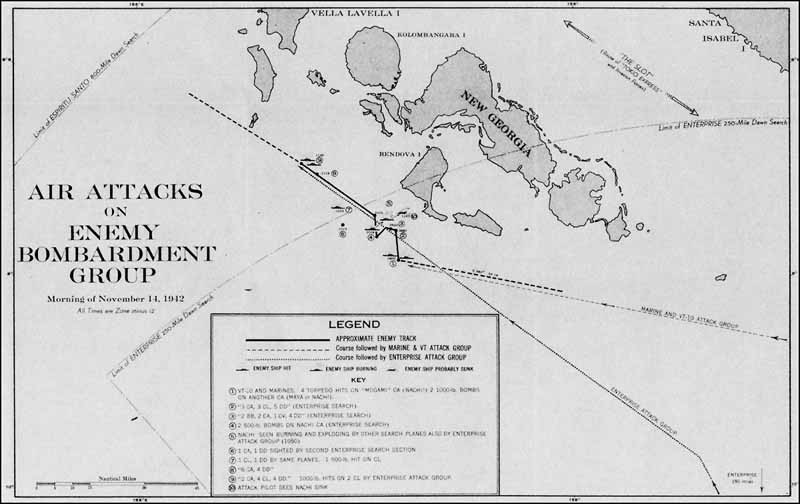

| Attacks on bombardment group | 44 | ||

| Attacks on the transports | 52 | ||

| Observations | 59 | ||

| Part III - Battleship Night Action of 14-15 November | 60 | ||

| Approach of Task Force LOVE | 60 | ||

| First phase of the action - 0000-0024 | 62 | ||

| Second phase - 0020-0045 | 66 | ||

| Third phase - 0045-0250 - destruction of the Kirishima | 72 | ||

| Observations | 77 | ||

| Epilogue - Last of the transports | 80 | ||

| Appendix I: TBS log of the Cruiser Night Action | 85 | ||

| Appendix II: Designations of United States naval ships and aircraft | 87 | ||

Charts and Illustrations

| Page | |

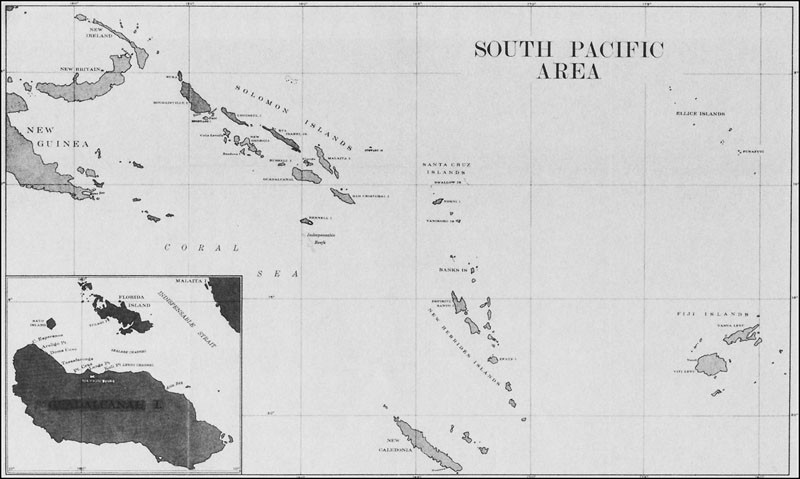

| Chart: South Pacific area | ix |

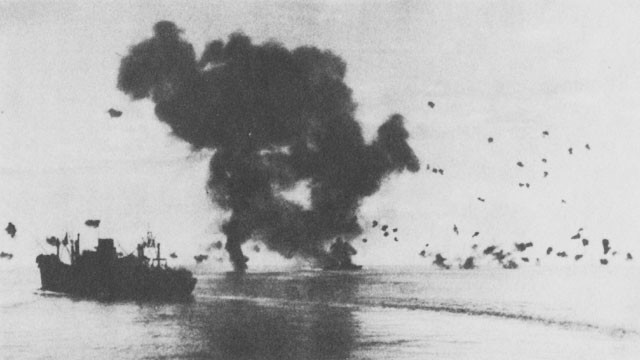

| Illustration: Enemy air attack of 12 November | x |

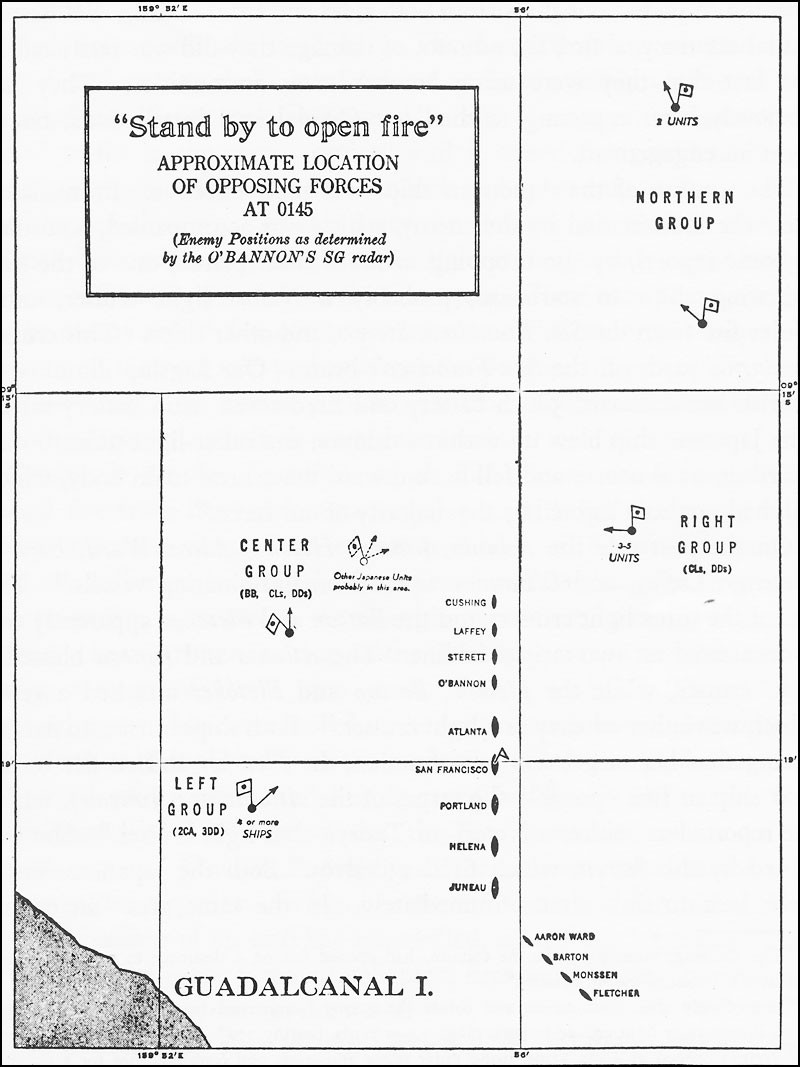

| Chart: "Stand by to open fire" | 19 |

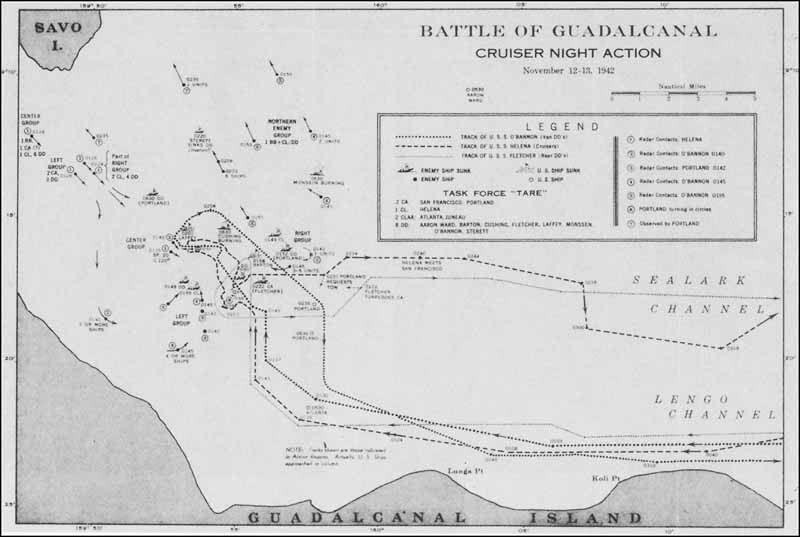

| Chart: Battle of Guadalcanal, Cruiser Night Action | 25 |

| Illustrations: Damage to San Francisco [1], [2] | 26 |

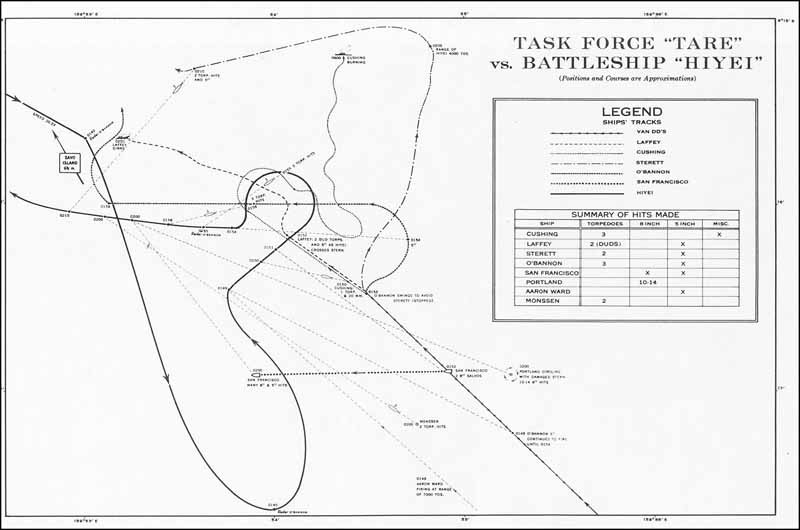

| Chart: Task Force TARE vs. battleship Hiyei | 27 |

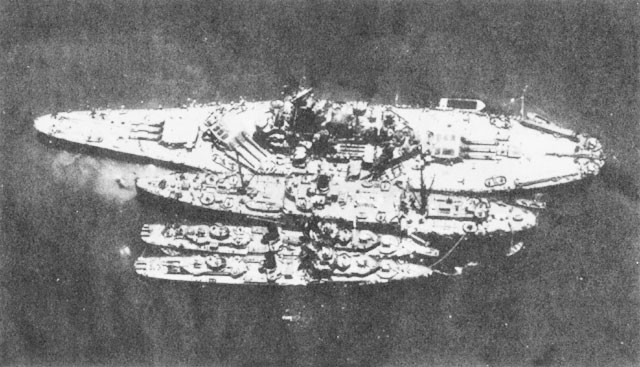

| Illustration: Battleship Kirishima | 28 |

| Chart: Air attacks on enemy bombardment group | 45 |

| Illustration: Burning Japanese vessels[1], [2] | 46 |

| Chart: Air attacks on transport group | 47 |

| Illustration: Yamazuki Maru and Kinugawa Maru beached on Guadalcanal | 48 |

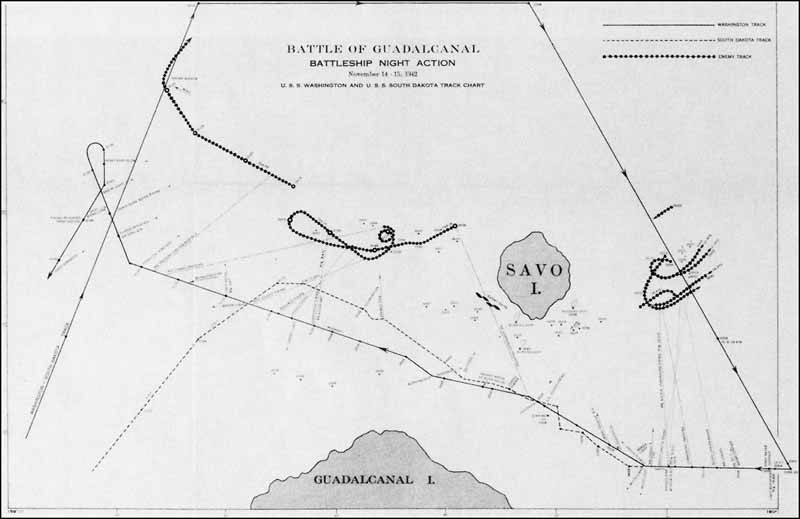

| Chart: Battle of Guadalcanal, Battleship Night Action | 63 |

| Illustration: Temporary repairs being made on South Dakota | 64 |

The Battle of Guadalcanal is one of a series of twenty-one published and thirteen unpublished Combat Narratives of specific naval campaigns produced by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War II. Selected volumes in this series are being republished by the Naval Historical Center [Naval History and Heritage Command] as part of the Navy's commemoration of the 50th anniversary of World War II.

The Combat Narratives were superseded long ago by accounts such as Samuel Eliot Morison's History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II that could be more comprehensive and accurate because of the abundance of American, Allied, and enemy source materials that became available after 1945. But the Combat Narratives continue to be of interest and value since they demonstrate the perceptions of naval operations during the war itself. Because of the contemporary, immediate view offered by these studies, they are well suited for republication in the 1990s as veterans, historians, and the American public turn their attention once again to a war that engulfed much of the world a half century ago.

The Combat Narrative program originated in a directive issued in February 1942 by Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S Fleet, that instructed the Office of Naval Intelligence to prepare and disseminate these studies. A small team composed primarily of professionally trained writers and historians produced the narratives. The authors based their accounts on research and analysis of the available primary source material, including action reports and war diaries, augmented by interviews with individual participants. Since the narratives were classified Confidential during the war, only a few thousand copies were published at the time, and their distribution was primarily restricted to commissioned officers in the Navy.

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the most complex naval engagement of the arduous Guadalcanal Campaign. Commencing on 11 November 1942, it lasted for five days and consisted of three phases: a cruiser night action, a carrier action, and a battleship night action. The

--iii--

Japanese precipitated the battle by launching a determined effort to land reinforcements in order to seize Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, the key American facility on the island. The U.S. Navy countered that effort and, in the ensuing action, both navies suffered heavy losses. But the Japanese failed to seize control of the seas around Guadalcanal or to significantly increase the strength of their force ashore. This action marked the last time that the Imperial Japanese Navy would launch a major offensive in the Guadalcanal area.

The Office of Naval Intelligence originally published this narrative in 1944 without attribution. Administrative records from the period indicate that Lieutenant Colin G. Jameson, USNR, authored the account. Prior to entering the Navy in 1942, Jameson was a free-lance, short-story writer who had published about 40 stories.

I wish to acknowledge the invaluable editorial and publication assistance offered in undertaking this project by Mrs. Sandra K. Russell, Managing Editor, Naval Aviation News magazine; Commander Roger Zeimet, USNR, Naval Historical Center Reserve Detachment 206; and Dr. William S. Dudley, Senior Historian, Naval Historical Center. We also are grateful to Rear Admiral Kendell M. Pease, Jr., Chief of Information, and Captain Jack Gallant, USNR, Executive Director, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps WW II 50th Anniversary Commemorative Committee, who generously allocated the funds from the Department of the Navy's World War II commemoration program that made this publication possible.

Dean C. Allard

Director of Naval History

--iv--

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D.C.

1 October, 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U.S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75½ and 76 of Naval Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

/s/

Roscoe E. Schuirmann

Rear Admiral, U.S.N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence.

--v--

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

/s/

E. J. King

ADMIRAL, U.S. N.,

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

--vi--

Battle of Guadalcanal

11-15 November 1942

--ix--

--x--

PART ONE

Enemy Air Attacks of 11-12 November and Cruiser Night Action of 12-13 November

INTRODUCTION

Perhaps the entire period between 7 August 1942, when the first Marines landed in the Solomons 1, and the final evacuation of Guadalcanal by the Japanese should be labeled "The Battle of Guadalcanal." Hardly a day went by during that 6 months which did not see action on land, in the air, or on the sea. Nevertheless, the climax and turning point of the campaign came with the shattering of the enemy's supreme effort to overwhelm the island between 11 and 15 November. During the desperate sea and air battles of those 5 days, Japanese losses as estimated by CINCPAC were 2 battleships sunk and 2 damaged, 4 cruisers sunk and 6 damaged, 8 destroyers sunk and 4 damaged, and 12 transports sunk or destroyed. Our losses consisted of 1 battleship damaged, 2 cruisers sunk and 3 damaged, 7 destroyers sunk and 4 damaged, and 3 cargo vessels damaged, 2 of these negligibly.

Beginning the first day of the Solomons operation, the Japanese had offered vigorous opposition to the consolidation and extension of our positions on Guadalcanal. During the remainder of August, they made many air attacks and attempted several landings, all of which were successfully driven off2 or mopped up.

With the coming of September they redoubled their efforts to bomb us off the island and to put reinforcements ashore. Small night landings by cruisers and destroyers - the so-called "Tokio Express" - became increasingly prevalent throughout the month and in early October. This method of reinforcement proved unsatisfactory, however, because few

__________

1 See Combat Narrative, "The Landing in the Solomons."

2 See Combat Narrative, "The Battle of the Eastern Solomons."

--1--

men and no heavy materiél could be carried. Consequently the enemy found it necessary to bring in large transports. Before this could be done, our air power on Guadalcanal had to be crippled, at least temporarily.

A surface force of cruisers and destroyers, which probably intended to put Henderson Field out of commission, was thrown back in the Battle of Cape Esperance on the night of 11-12 October. 3 Japanese losses were heavy, but 2 nights later they came back and succeeded in shelling the field for an hour and 20 minutes. By the morning of the 15th only 1 of our bombers and 10 fighters were in a condition to take to the air, and they were unable to prevent a convoy of 6 transports from coming in. Our lone bomber sank one of these ships. Other SBD's were flown in by noon, and with the help of Army B-17's they set 4 beached transports afire and badly damaged the remaining one. But an enemy force estimated by General Vandegrift to number 16,000 men had already reached shore.

Frequent shelling of Henderson Field continued, as well as daily air attacks. On 23, 24, and 25 October there were strong Japanese land assaults. At sea a major carrier engagement took place on the 26th - the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands.4 In this action a strong enemy carrier and battleship force which was covering transports and auxiliaries was intercepted about 350 miles northeast of Guadalcanal. Although we suffered the sinking of the Hornet and the damaging of the Enterprise, the enemy lost many of the planes comprising the air groups of four carriers, two of which were damaged.

Thereafter the Japanese intensified their efforts to interrupt our communications, achieving considerable success. But they in turn were forced to rely on the "Tokio Express" for reinforcements. An American Task Force of 24 submarines which had begun to operate in the Solomons made this makeshift even less satisfactory. During the first half of November the submarines inflicted the following damage on Japanese communications: sunk, 1 and probably 2 destroyers, 1 light minelayer, 1 oiler, 3 cargo vessels; damaged, 1 seaplane tender (Chiyoda class), 1 heavy cruiser, 1 light cruiser (Natori class), 1 destroyer, 3 or more cargo ships. During the same period surface craft probably destroyed 2 hostile submarines, while Guadalcanal planes probably sank 2 midget submarines.

3 See Combat Narrative, "The Battle of Cape Esperance."

4 See Combat Narrative, "The Battle of Santa Cruz Islands."

--2--

The Navy and the Marines were cooperating to push the Japanese back on land. Beginning at 0030 on 30 October, the light cruiserAtlanta and four destroyers bombarded enemy positions back of Point Cruz for 8 hours. Next morning the Fifth Marines struck across the Matanikau River, supported by such ships as were available. On 3 November our troops had advanced beyond Point Cruz.

During the preceding night Japanese cruisers and destroyers landed 1,500 men and some artillery east of Koli Point. Our offensive to the west was checked to counter this new threat. But because of the heavy damage Japanese supply lines had been receiving at the hands of the Navy, the enemy failed to reinforce this new landing and was unable to launch a general attack from all sides as he had planned.

On 4 November the San Francisco, Helena, and Sterett bombarded the new force east of Koli Point, setting fires and destroying stores and ammunition. By the 11th only an estimated 700 Japanese remained alive. They escaped to the jungle, where they were exterminated during the ensuing month by the Second Marine Raider Battalion and by disease.

By November our air defenses on the island had been greatly improved. The development of landing facilities in the Lunga area was proceeding rapidly, and the striking power of Marine and Army aircraft was beginning to make itself felt. On 7 November, Guadalcanal planes attacked an enemy light cruiser and 10 destroyers. They scored 1 bomb and 2 torpedo hits on the cruiser, damaged 2 destroyers, and shot down 16 planes.

Under cover of darkness the Japanese continued doggedly to put ashore troops and supplies from cruisers and destroyers and by means of landing boats from neighboring islands. Our PT boats from Tulagi attacked repeatedly. On the night of 6-7 November they sank a destroyer. On other nights they damaged two more. Many landing craft were destroyed by planes and surface guns.

The Japanese were not succeeding in improving their position, and it became apparent that they had decided to strike another blow of major proportions. Enemy surface forces were concentrating in the Rabaul-Buin area. By 12 November these were estimated to include 2 carriers, 4 battleships, 5 heavy cruisers, about 30 destroyers, and the transports necessary for a decisive invasion attempt. Our aircraft noted at least 60

--3--

ships in the Buin-Faisi-Tonolei anchorages, including 4 probable battleships, 6 cruisers, and 33 destroyers.

To ward off the impending attack, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Commander South Pacific Force and South Pacific area, had no such imposing strength available. Only one carrier, the Enterprise, was on hand at Noumea, and she was damaged and would not be fully ready for action until 21 November.5 We were inferior in land-based aircraft as well.

Guadalcanal had received some reinforcements from Efate on 6 November. Seven more United States transports were scheduled to sail from other ports with supplies and reinforcements which were even more vitally important. If Admiral Halsey's combatant forces could not protect them and simultaneously counter the new enemy offensive, we would be obliged to retire from the Solomons, thus jeopardizing the entire Allied position in the South Pacific.

The Guadalcanal supply operation had been assigned to Task Force TARE 6, Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, based on Noumea, New Caledonia and Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides. This force was organized as follows:

Task Force TARE, Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner:

Noumea Group, Admiral Turner:

One heavy cruiser:

Portland, Capt. Laurance T. DuBose.

One light cruiser (antiaircraft):

Juneau, Capt. Lyman K. Swenson.

Four destroyers:

Barton, Lt. Comdr. Douglas H. Fox.

Monssen, Lt. Comdr. Charles E. McCombs.

O'Bannon, Comdr. Edwin R. Wilkinson.

Shaw, Comdr. Wilber G. Jones.

Four transports, Capt. Ingolf N. Kiland:

McCawley (FF), Capt. Charlie P. McFeaters.

Crescent City, Capt. John R. Sullivan.

President Adams, Comdr. Frank H. Dean.

President Jackson, Comdr. Charles W. Weitzel.

__________

5 The Saratoga was just leaving Pearl Harbor after extensive antiaircraft improvements, and repairs made necessary by a torpedo hit received from a submarine on 31 August.

6 Official designations of Task Forces have been omitted from all Combat Narratives in the interest of security. The flag names for the first letters of surnames of commanding officers have been substituted.

--4--

Espiritu Santo Group, Section One, Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan:

Two heavy cruisers, Rear Admiral Mahlon S. Tisdale

Pensacola (F), Capt. Frank L. Lowe.

San Francisco (FF), Capt. Cassin Young.

One light cruiser:

Helena, Capt. Gilbert C. Hoover.

Six destroyers, Capt. Thomas M. Stokes (ComDesDiv TEN):

Buchanan, Comdr. Ralph E. Wilson.

Cushing (F), Lt. Comdr. Edward N. Parker.

Gwin, Lt. Comdr. John B. Fellows, Jr.

Laffey Lt. Comdr. William E. Hank.

Preston, Comdr. Max C. Stormes.

Sterett, Comdr. Jesse G. Coward.

Espiritu Santo Group, Section Two, Rear Admiral Norman Scott:

One light cruiser (antiaircraft):

Atlanta (FF), Capt. Samuel P. Jenkins.

Four destroyers, Capt. Robert G. Tobin (ComDesRon TWELVE):

Aaron Ward (F), Comdr. Orville F. Gregor.

Fletcher, Comdr. William M. Cole.

Lardner, Lt. Comdr. Willard M. Sweetser.

McCalla, Lt. Comdr. William G. Cooper.

Three cargo vessels:

Betelgeuse, Comdr. Harry D. Power.

Libra, Comdr. William B. Fletcher, Jr.

Zeilin, Capt. Pat Buchanan.

Embarked on board the Noumea Group of Task Force TARE were the Army One Hundred Eighty-Second Reinforced Regiment (less Third Infantry Battalion); Battery "L," Eleventh Marines (155-mm. howitzer); the Two Hundred Forty-Fifth Field Artillery Battalion (USA); the One Hundred First Medical Regiment; 1,300 officers and men of the Fourth Marine Replacement Battalion; Co. "A," Fifty-Seventh Engineers (USA); 1 quartermaster company; 1 ordnance company; and 372 naval personnel as reinforcements for the Naval Local Defense Force, as well as considerable ammunition reserves.

The Espiritu Santo Group carried the First Marine Aviation Engineer Battalion, Marine replacements, ground personnel of Marine Air Wing ONE, aviation engineering and operating material, ammunition and food.

In all, about 6,000 men were to be put ashore on Guadalcanal. To protect the landing, Admiral Turner had a total of 3 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 2 light cruisers (antiaircraft), and 14 destroyers - 20 combatant

--5--

ships. He was also to employ this force to seek out and destroy such enemy surface forces as might be found in the Guadalcanal area.

Available as support at Noumea was Task Force KING, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid. This group was organized as follows:

Task Force KING, Admiral Kinkaid:

One aircraft carrier:

Enterprise (FF), Capt. Osborne B. Hardison.

Two battleships, Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr., (ComBatDiv SIX):

South Dakota Capt. Thomas L. Gatch.

Washington (F), Capt. Glenn B. Davis.

One heavy cruiser, Rear Admiral Howard H. Good:

Northampton (F), Capt. Willard A. Kitts III.

One light cruiser (antiaircraft):

San Diego, Capt. Benjamin F. Perry.

Eight destroyers, Comdr. Harold R. Holcomb (ComDesRon TWO):

Anderson, Lt. Comdr. Richard A. Guthrie.

Benham, Lt. Comdr. John B. Taylor.

Clark (F), Lt. Comdr. Lawrence H. Martin.

Hughes, Comdr. Donald I. Ramsey.

Morris, (Comdr. Arnold E. True, ComDesDiv FOUR), Lt. Comdr. Randolph B. Boyer.

Mustin, Comdr. Wallis F. Petersen.

Russell, Comdr. Glenn R. Hartwig.

Walke, Comdr. Thomas E. Fraser.

Starting Tuesday, 10 November, planes stationed at Espiritu Santo, the Fijis, and Henderson Field were to scout north and west against surface craft and submarines, and to provide fighters, bombers, and antisubmarine patrol in the Guadalcanal area proper. On 11, 12, and 13 November, enemy air fields in range of Guadalcanal were to be bombed. 7

APPROACH TO GUADALCANAL - THE PLAN

| Sunday, 8 November | ||

| 1500 | Noumea group of Task Force TARE sails. | |

| Monday, 9 November | ||

| 0830 | Section Two of Espiritu Santo group departs. | |

| Tuesday, 10 November | ||

| 0500 | Section One of Espiritu Santo group gets under way. | |

| 0915 | Southard probably destroys Japanese SS off San Cristobal. | |

__________

7 On 10 November COMSOWESPAC (Gen. Douglas MacArthur) was requested to attack shipping in the Buin-Falsi-Tonolei area from the 11th to the 14th. The shortage of aviation gasoline at Guadalcanal unfortunately prevented staging B-17's from Espiritu Santo through Henderson Field in order to reach this sector.

--6--

| 1500 | Shaw joins Noumea group of Task Force TARE. | |

| 1700 | Pensacola, Gwin, and Preston detached from TARE to reinforce Task Force KING. | |

| Wednesday, 11 November | ||

| 0500 | Task Force TARE'S rendezvous southeast of San Cristobal. | |

The four transports of Task Force TARE'S Noumea group with the Portland, Juneau, Barton, Monssen, and O'Bannon sortied on Sunday, 8 November, at 1500. 8 The Shaw left on the 9th, joining the rest of the group on the 10th. Admiral Scott's section of the Espiritu Santo group sailed on Monday, 9 November, and passed north of San Cristobal Island to avoid a group of submarines and to escape discovery by the enemy's long range air scouts based in the Buin region. However, these vessels were sighted by a large twin-float Japanese seaplane on Tuesday morning. The aircraft apparently was one of two or three of its type which the enemy had started basing on a tender in a location believed at the time to be the Swallow Islands. Its report was possibly responsible for the air attack on the transports at Guadalcanal the next day.

Admiral Callaghan's section of Task Force TARE departed from Espiritu Santo on Tuesday, 10 November. At 1700, the Pensacola,Gwin, and Preston were detached by COMSOPAC as reinforcements for Task Force KING, which was still at Noumea, but which was preparing to sail to support Admiral Turner.9 The remainder of Admiral Callaghan's vessels rendezvoused with the Noumea transport group near the eastern end of San Cristobal on Wednesday morning. To prevent air discovery by the Swallow Islands seaplanes, and because a submarine was reported sunk to the west of San Cristobal by the fast minesweeper Southard (on her way to Aola Bay with troops), a new route south of the island was selected. For the rest of the day the transports and their four escorting destroyers operated about 20 miles in advance of our main fighting strength.

By the afternoon of Monday, 9 November, there was no longer any doubt that the Japanese had set in motion a vast amphibious offensive

__________

8 All times in Part I are Zone minus 11.

9 On 9 November COMSOPAC had placed the damaged Enterprise at Noumea on 24-hour notice, and on the 10th Task Force KING was ordered to assume readiness to get under way within one hour, effective at 2200.

--7--

against Guadalcanal, probably with strong air support.10 Admiral Turner's considered judgment, together with the reconnaissance reports already mentioned, led him to estimate that the enemy planned to employ 2 to 4 carriers, possibly 2 to 4 fast battleships, as well as cruisers and destroyers, to the northward of Guadalcanal. As protection for at least 1 division of troops in 8 to 12 transports, 2 heavy cruisers, 2 to 4 light cruisers, 12 to 16 destroyers, and several light minelayers would probably operate eastward from Buin. It was anticipated that land-based planes would start bombing Guadalcanal on Tuesday, and that the airfield would perhaps be bombarded by surface craft Wednesday night. A continuous and concentrated carrier air attack on Henderson Field would probably take place on Thursday, with further naval bombardment and landings, perhaps after midnight, on Thursday night, near Cape Esperance or Koli Point. As the narrative progresses, it will be seen that many of these hypotheses were accurate, although no Japanese carriers were directly involved.

Since the enemy invasion force was expected in the Guadalcanal area by Friday, 13 November, it was most important that our transports finish landing their reinforcements and supplies on Thursday and make good their escape. Divorced from responsibility for protecting the transports, the combatant units would be in a better position to carry the fight to the Japanese. If Task Force TARE, with its exceptional antiaircraft strength, managed to turn back the enemy's initial onslaught, cost what it might, then our land-based aircraft on Guadalcanal, plus the planes of the Enterprise and the battleships of Task Force KING, might dash in and destroy or cripple the main Japanese surface forces.

According to the original plan, Admiral Scott's cargo vessels from Espiritu Santo were due off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal, at 0530 on Wednesday, 11 November. Admirals Turner and Callaghan were to reach Indispensable Strait that night, after which the Noumea transports would pass through Lengo Channel, if favorable reports were received from minesweepers, and anchor at the unloading point Thursday morning. Admiral Callaghan was to precede the transport group and arrive at the east end of Sealark Channel about 2200. There he was to be joined by Admiral Scott's fighting vessels, except for three destroyers detached as

__________

10 Further evidence of the enemy operation was provided on Tuesday when our aircraft discovered 5 Japanese destroyers 210 miles northwest of Guadalcanal. Eight SBD's and 15 F4F-4's attacked the ships, and 3 near-hits were scored on each of 2 destroyers. One SBD was lost, but the pilot and gunner were saved.

--8--

antiaircraft and antisubmarine protection for the three Espiritu Santo transports. During the night he was to pass through Sealark Channel to Savo Sound and strike any enemy forces he might find, with particular attention to possible transports in their rear. Retiring eastward to Indispensable Strait at daybreak, he was to take up a support position until about 1800, when he would return to cover the final unloading and departure. This was tentatively scheduled for 2200, unless it was found necessary to return the next day to complete the operation, or the expected attack failed to take place. If the Japanese bombarded Guadalcanal or Florida Island during Thursday night, or attempted to land troops, Admiral Callaghan was to be on hand to oppose them.

Later, this plan was changed slightly. On Thursday Admiral Callaghan was to return from Indispensable Strait, as soon as he made sure no enemy vessels were present, and cover the unloading, which was to proceed at top speed all day. If the enemy attacked, he was to form a circular screen at a distance of 1,000 yards from the nearest transports. As far as the landing proper was concerned, all troops were to be put ashore first, carrying 2 days' rations, water, barracks bags, and one unit of fire, so that they would be ready for action in case the Japanese did succeed in making a landing. Those who were on the beach were to work continuously at unloading the boats. None of the Marines already present on Guadalcanal would be available, since they were dealing with the Japanese land forces.

Admiral Turner stated emphatically to all officers concerned that the safety of our position on the island depended entirely on the rapidity with which the ships were emptied.

FIRST PHASE - ENEMY AIR ATTACKS OF 11 AND 12 NOVEMBER

Wednesday, 11 November

Admiral Scott reached Guadalcanal at 0530 on Wednesday, as expected, and began unloading supplies on Lunga Point. The sea was calm, with --9-- |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

the wind about force two. Surface visibility was unlimited; cloud ceiling was 10,000, with formations low over the mountains on Guadalcanal. At 0905 Radio Guadalcanal reported that 10 bombers and 15 fighters were approaching from the northwest and should arrive at about 0930. At 0910 they were located on a bearing of 300° T., distance 80 miles. Seven minutes later the bearing was 280° T., distance 43. At 0920 Admiral Scott got under way and formed antiaircraft disposition as follows: The Betelgeuse, Libra, and Zeilinwere in column. The Atlanta was several hundred yards ahead of them. The Aaron Ward, Fletcher, Lardner, and McCalla were stationed on the flanks of the column at a distance of 1,500 yards from it. The formation was steaming on course 000° T., speed 15.

At 0930 "bandits" were reported approaching from 230° T., distance 20, and coming in fast. Five minutes later, 9 dive bombers of the Aichi 99 type emerged from the clouds over Henderson Field at about 10,000 feet. The planes were in a rough T formation and peeled off from the right side. Shortly before the first one started its dive, about 0938, the Atlanta and the other ships opened fire. There were bursts close to the leading plane, which sheered away and jettisoned its bombs. Several other aircraft were set afire and downed in the sea. Marine land-based fighters had begun to take a hand, and a single F4F-4 accounted for 4 of the 5 kills scored against the 15 Zero fighters which were protecting the bombers. The latter chose the transports as targets. The Zeilin received 3 near-hits and 1 hold was flooded. The Libra and Betelgeuse were slightly damaged by other near-hits. Personnel casualties were considerable. About half the bombers escaped destruction by antiaircraft fire but were downed by fighter planes during their withdrawal. Six of our planes and 4 pilots were lost, principally because of the inexperience of the personnel.

Unloading operations were resumed. At 1127 a flight of 25 medium and heavy level bombers, protected by 5 Zeros, came in at 27,000 feet and began attacking ground installations on the island. The transports received no attention, but antiaircraft fire was opened. Most bursts were short, but 1 bomber was believed destroyed. The landplanes downed 6 aircraft for certain and probably 2 others. Henderson Field antiaircraft accounted for 1 additional bomber. One Grumman fighter was lost.

As dusk approached (about 1800), Admiral Scott retired to Indispensable Strait for the night. It was found necessary to send theZeilin back to Espiritu Santo with the Lardner as escort. The damaged ship

--10--

proceeded under her own power at 10 knots and arrived safely on 14 November.

Meanwhile Admiral Turner's and Admiral Callaghan's combined force was approaching on schedule. On the morning of the 11th thePortland's four seaplanes had been sent back to Espiritu Santo, because the Battle of Savo Island, when the Canberra, Astoria, Quincy, and Vincennes were lost, had demonstrated that during action the presence of cruiser planes on board is a serious fire hazard. The evening air search from Guadalcanal showed no enemy planes or ships in the vicinity, but this was not considered conclusive, so Admiral Callaghan proceeded at high speed in advance of the transports. After reinforcement by Admiral Scott's combatant ships in Indispensable Strait, he entered Savo Sound at 2330 and made two thorough sweeps east and west of Savo Island. Nothing was found. The entire group remained in the sound and joined Admiral Turner and the transports when they appeared at dawn on Thursday.

| Thursday, 12 November | ||

| 0530 | Transports arrive at Guadalcanal. | |

| 0718 | Enemy shore battery opens up and is silenced. | |

| 1010 | Friendly aircraft fired on. | |

| 1035 | Enemy BB's sighted, 335 miles | |

| 1045 | Enemy DD's, 195 miles. | |

| 1317 | Guadalcanal reports enemy bombers and fighters which could arrive at 1330. | |

| 1405 | Torpedo planes attack. | |

| 1419 | Action terminated. | |

| 1450 | "Two CV and two DD" sighted, 150 miles. Never confirmed. | |

| 1525 | Transports anchor again. | |

Admiral Turner's four transports anchored off Kukum Beach at 0530 on Thursday, and the Betelgeuse and Libra anchored 2 miles east of Lunga Point. Combatant vessels were disposed about the transports in two protective semicirdes. The San Francisco, Portland, andHelena lay 3,000 yards away. The Atlanta, Juneau, 11 destroyers, and the fast minesweepers Hovey (Lt. Comdr. Edwin A. McDonald) and Southard (Lt. Comdr. John G. Tennent III), 11 which had been sweeping Lengo Channel and the transport area, were stationed 6,000 yards away. The screen had orders to close to 1,000 yards if an air attack eventuated and the transports had to get underway. One submarine contact north of Lunga

___________

11 The Hovey had arrived from Espiritu Santo with aviation gasoline on Tuesday. The Southard had reached Tulagi the same day after disembarking her troops at Aola Bay.

--11--

Point was reported that morning, but depth charge attacks produced no results.

At 0718 a Japanese 6-inch shore battery opened up on the Betelgeuse and Libra. Counter-battery work by our shore guns and shellfire from the Helena, Barton, and Shaw soon caused it to cease firing. Neither of the cargo vessels was hit, and debarkation continued. Subsequently, the Buchanan and Cushing attacked enemy shore installations farther to the west. Many large fires and explosions were observed. When the range closed to about 1,500 yards, the destroyers used 1.1-inch and 20-mm. machine guns on a number of large Japanese landing boats which had been previously riddled by the fire of ships and aircraft, and further destruction was caused among them. The attack was facilitated by an unidentified but friendly cruiser-type plane which dived on useful targets.

The expected air attack did not take place, but at 1010 twelve of our aircraft, which were being ferried from Espiritu Santo, were fired on by mistake, fortunately without serious damage. From their low approach it was thought that they were torpedo planes.

At 1317 Admiral Turner received from Radio Guadalcanal a dispatch saying that a flight of enemy bombers and fighters was passing Tonolei and heading southeastward. These planes could reach Guadalcanal by 1330, so orders were immediately given to get underway and form in the previously designated antiaircraft disposition (Left column: McCawley, Crescent City, and Libra. Right column: President Jackson, President Adams, Betelgeuse. Screen as noted above). This was completed by 1340, and a course of 340° T. had been set, when another dispatch was received. Shore radar had picked up the planes, and the scheduled arrival time was now 1415. The aircraft actually appeared at 1405, after approaching low behind Florida Island so as to remain out of sight as long as possible. There were 20-25 torpedo bombers (Mitsubishi Type 1) and 8 Zero fighters. Only the bombers were immediately sighted by our vessels. They headed toward the transport anchorage in a long line abreast, skimming so close to the water that they occasionally dipped below the horizon. Their speed was approximately 200 knots. As they came within range, the screening ships to the north and east, which were not masked by our own vessels, opened up. Their fire was so devastating that several enemy planes were immediately blasted from the air and others were set ablaze. The survivors, in a desperate attempt to avoid the holocaust, split into two groups, one swerving across the bows of our ships,

--12--

and the other swinging around astern of them to escape westward along the coast. So violent were their maneuvers that their torpedoes seemed to spill into the water haphazardly, as if impelled by centrifugal force alone.

All attempts to get away were unavailing, however. Our land-based fighters (20 F4F-4's and 8 P-39's), which had been attacking the covering flight of Zeros, dived on the remnants of the bombers which were fleeing westward and sent one after another flaming into the sea.

The fighters had already accounted for five Zeros and now they eliminated every remaining bomber but one. Kills claimed by ships and aircraft are conflicting, but only one bomber was later reported passing over New Georgia Island. In addition to those destroyed by fighters and antiaircraft, one was downed by .50-caliber fire from the landing boats scattered off Lunga Point. Our plane losses were three F4F-4's and one P-39. 12

One aircraft which dropped its torpedo on the starboard side of the McCawley was set on fire by that ship's guns. The pilot headed to crash the San Francisco. Although he was practically parallel to her, he managed to strike Battle II and the after control structure with one wing. The plane then sideswiped the ship and fell into the water. Several fires broke out on the San Francisco. They were soon extinguished, but a total of 30 lives had been taken, and many other men had been badly burned. The after antiaircraft director and the FC radar had been put out of commission, and the three 20-mm. guns on the after superstructure were demolished. The crews of these guns stayed at their stations and maintained fire until they were killed by the plane crashing into them.

During the course of the attack the enemy torpedo planes flew so close to the water that several of our ships were struck by antiaircraft fire. The Buchanan received a direct hit on No. 2 stack by a 5-inch shell, which caused 13 casualties, including 5 dead, and considerable material damage.

___________

12 In the fever of repelling air attack it is practically impossible for individual ships and aircraft to make accurate estimates of the number of planes shot down and damaged by their own guns. In this action, for example, 25 bombers at most were employed. One was credited to the landing boats, and 1 escaped, leaving only 23 which could possibly have been downed by fighters and surface craft. Nevertheless, 59 sure kills were reported. The fighters claimed 16 and the ships 43, as well as 18 possibles and 10 damaged. The Fletcher alone maintained that she had positively downed 5 planes and assisted in the destruction of 3. Juneau personnel reported that she had blasted 6 bombers out of the air, while the Betelgeuse claimed 5. The Southard claimed 3 shot down, 3 possibles and 2 damaged. The Sterett stated that she had destroyed 4 planes and scored 2 possibles. The Helena's record was 4 kills.

--13--

The transports anchored again at about 1525, after losing 2 hours' unloading time.

* * *

Earlier in the day, reports from our scouting aircraft revealed that strong enemy surface forces were bearing down on Guadalcanal and were close enough to arrive during the night. Three separate groups were sighted:

- Two battleships or heavy cruisers, one heavy or light cruiser, and six destroyers sighted at 1035 bearing 008° T. from Guadalcanal (practically due north of the northwest tip of Malaita Island), distance 335 miles. This group was later identified as two Kongo-class battleships, 13 one Tenryu-class light cruiser, and six destroyers.

- Five destroyers sighted at 1045 bearing 347° T., about 100 miles due north of Santa Isabel Island (distance from Guadalcanal, 195 miles). This was more likely one or two Natori-class light cruisers and three or four destroyers.

- Two small carriers and two destroyers sighted at 1450 bearing 264° T. (south of New Georgia Island), distance 150. These "carriers" were never confirmed as such because of exceptionally heavy cloud cover and rain squalls and were perhaps seaplane tenders taking float planes to Rennell Island. A Marine attack group sent out to destroy them was forced to turn back by the weather and approaching darkness.

No transports were discovered heading for Guadalcanal, so it was thought that the enemy's intent was to attack our own transports that night in Indispensable Strait or to bombard our Guadalcanal positions. Considering the Japanese strength previously reported at Buin, it was possible that additional cruisers and destroyers might be on the way, and the presence of heavy cruisers in the ensuing action proved that this was the case. The first two groups mentioned above were probably from Truk.

To meet this gathering armada, Rear Admiral Turner now had at his disposal 2 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 2 antiaircraft light cruisers, 11 destroyers, and 2 fast minesweepers, besides his transports. He decided to assign to Admiral Callaghan all the cruisers and 8 destroyers, thus leaving 1 damaged destroyer, 2 low-fuel destroyers, and 2 minesweepers for the protection of the transports.

__________

13 It is possible that one of these was a Fuso, though not likely in view of the Japanese habit of operating their Kongo battleships in company. The other was definitely a Kongo - the Hiyei.

--14--

By late afternoon it was seen that the transports could be 90 percent unloaded before night, but that it would be several days before the cargo vessels (Betelgeuse and Libra) were emptied. In view of the enemy's approach in force it was determined that all the transports should be withdrawn, after which Admiral Callaghan would strike the Japanese in Indispensable Strait or Savo Sound and damage them as much as possible. This delaying action might make it possible for Task Force KING to blast the major enemy landing attempt with the help of the planes from Henderson Field. Admiral Kinkaid's force had not sailed from Noumea till Wednesday noon and was not close enough to help during the coming night. It was now steaming to get the Enterprise in fly-off position south of Guadalcanal on the morning of Friday, the 13th.

SECOND PHASE - CRUISER NIGHT ACTION OF 12-13 NOVEMBER14

"This desperately fought action...has few parallels in naval history. We have come to expect, and to count on, complete courage in battle from officers and men of the United States Navy. But here, in this engagement, we had displayed for our lasting respect and admiration, a cool but eager gallantry that is above praise. These splendid ships and determined men won a great victory against heavy odds. Had this battle not been fought and won, our hold on Guadalcanal would have been gravely endangered." - R. K. TURNER.

| 12-13 November | ||

| 1815 | Task Force TARE leaves Savo Sound. | |

| 0000 | Admiral Callaghan returns via Lengo Channel for a sweep of Savo Sound. | |

| 0124 | Helena's SG radar picks up three enemy groups--nearest 27,100 yards. | |

| 0148 | "Odd ships fire to starboard, even ships to port." | |

| 0149 | Natori CL blows up, Natori or Tenryu CL on fire. Enemy CL or CA also on fire. Sinks a few minutes later. Enemy DD blows up. Two others on fire. | |

| 0150 | Atlanta sinks a DD and is torpedoed. | |

| 0151-2 | Atlanta on fire. San Francisco attacks BB Hiyei. Portland sinks a Hibiki DD. Laffey shells Hiyei and is knocked out and torpedoed. | |

___________

14 Action in this battle was confused from the start, and the reports are sometimes conflicting as to detail and timing. The divergences have been reconciled as far as possible, but it is probable that inaccuracies persist in the story as here given.

--15--

| 0154 | "Cease firing, our ships." | |

| 0155-6 | Cushing and O'Bannon torpedo Hiyei. Barton blows up. Portland and Juneau have been torpedoed. | |

| 0200- 0204 | Laffey blows up. San Francisco and Portland attack Hiyei. San Francisco seriously damaged. Helenasilences cruiser. | |

| 0205 | Monssen torpedoes Hiyei. | |

| 0210 | Sterett torpedoes Hiyei. | |

| 0212 | Helena tries to reassemble our forces. | |

| 0220 | Sterett sinks a Fubuki DD. | |

| 0240 | Monssen abandoning ship. | |

| 0630 | Portland sinks Shiguri DD. | |

| 1101 | Juneau again torpedoed and blows up. | |

| 1700 | Cushing sinks. | |

| 2015 | Atlanta sinks. During the night Hiyei also sinks, after having been bombed by planes all day. |

At 1815 Task Force TARE proceeded eastward out of Savo Sound. The transport group and its screen (McCawley (Admiral Turner),Betelgeuse, Crescent City, Libra, President Adams, President Jackson, Buchanan, Hovey, McCalla, Shaw, Southard) left via Lengo Channel. The combatant group, commanded by Admiral Callaghan in San Francisco and Admiral Scott in Atlanta, used Sealark Channel and preceded the transports into Indispensable Strait, which it swept before they arrived. Admiral Turner then headed for Espiritu Santo, where he arrived on Sunday. Admiral Callaghan reversed his course and proceeded toward Lengo Channel. His ships were in Battle Disposition "Baker ONE" - the single column being led by the Cushing, followed by the Laffey, Sterett, O'Bannon,Atlanta, San Francisco, Portland, Helena, Juneau, Aaron Ward, Barton, Monssen, and Fletcher, in that order. The distance maintained between the destroyers was about 500 yards. Between cruisers and between divisions it was 700-800 yards. Signals were made by voice code over TBS. 15

At 0000 Friday the 13th, the 13 ships entered Lengo Channel at 18 knots for a search of the Savo Island area, which since 7 August, 1942 has witnessed the destruction of as mighty an array of naval power as was sunk at the Battle of Jutland. The moon had set, the sky was overcast, the night was very dark. The sea was calm, and a slight breeze--9 to 10 knots--was blowing from south southeast.

___________

15 Super frequency radio.

--16--

The first sign of the enemy's presence was a probable torpedo wake which was sighted by the O'Bannon at 0036. About half an hour later the same ship observed a bright light on the port bow, apparently on the Guadalcanal beach. The San Francisco saw two white lights, with the eastern one sending long flashes. The same phenomenon had been noted on the night of 11-12 October just before the Battle of Cape Esperance. Now a red air raid warning as well ("planes overhead") was received from Guadalcanal Control. Look-outs saw unidentified aircraft above with running lights on.

Near Lunga Point at 0124, while on course 280° T., the Helena's SG radar picked up three groups of enemy vessels, the first bearing 312° T. at 27,100 yards, the second 310° T. at 28,000 yards, and the third 310° T. at 32,000 yards. This information was relayed to Admiral Callaghan by TBS,16 because the flagship was not provided with SG radar. Only the Portland, Helena, Juneau, O'Bannon, andFletcher possessed this invaluable equipment.

From the strength of the signals received by the Helena it was believed that the two nearer groups constituted part of the screen for the more distant one. At 0130 the Helena's radar plot reported target course was approximately 134° T., speed 20 (later altered to 120° T., speed 20-23). Other radar contacts confirmed the fact that there were 3 groups rapidly closing our column, which was now on course 000° T., 1 being ahead and 2 to port. Course was changed to 310° T. to steam directly for the enemy, but at 0137 it was shifted back to 000° T. At 0140 the O'Bannon made SG radar contacts as follows: one group bearing 287° T., distant 11,000 yards, and containing 3 or more units; a second group bearing 318° T., distant 8,500 yards, and composed of 2 or 3 units; and a third group bearing 042° T., distant 6,000 yards, and containing 3 units. From the earlier air reports and later observations it seems clear that the left-hand group consisted of 2 heavy cruisers (1 being a Maya-class) and 2 or 3 destroyers. The center group included 1 battleship of the Kongo class (the Hiyei) with a Tenryu-class light cruiser and several destroyers. The right-hand group probably contained 2Natori-class light cruisers and 3 or 4 destroyers. To the north was another battleship with escorting vessels.17 All told, there were between 18 and 20 ships. Our squadron was not only outnumbered but heavily outclassed.

__________

16 But the delay in transmission amounted to 6 minutes, during which time the opposing forces moved approximately 4 miles closer together.

17 This group was not discovered till 0145. See p. 58.

--17--

The picture at the time, however, was not clear to Admiral Callaghan, who had apparently received radar information from the Helenaalone. At 0139 that ship reported four targets in line but gave no bearing or range. The OTC requested the distance. Just as this was being received, ComDesDiv TEN in the Cushing announced that ships were crossing from port to starboard at 4,000 yards. Later theHelena reported a total of 10 targets.

The TBS, in the words of Admiral Spruance, "became chaotic with queries and incomplete information." 18 At 0142 the Cushinginformed the OTC that she was turning left to get in position to fire torpedoes at the ships crossing and asked leave to do so. This permission was granted by Admiral Callaghan, and course was changed to 310° T. The Cushing turned to port but did not fire because she recognized the targets as destroyers which were sheering away. Also, the OTC had ordered all ships back to course 000° T. again.

With this latest shift our column became disorganized. The Atlanta was forced to turn left to miss the O'Bannon which was making many rudder changes to avoid ramming the Sterett. The OTC ordered the Atlanta to return to course. Several other times he requested the column to maintain 000° T., but the order did not get through to all vessels. Some steered 315° T. The cruisers turned as far left as 270° T. The San Francisco maintained this course and went between the left and center enemy groups, 2,000 and 3,000 yards away respectively, leaving the Atlanta on her starboard hand. Meanwhile the van mingled with the Japanese ships and a melee existed even before firing began.

At 0145 Admiral Callaghan ordered the Task Force to stand by to open fire, range 3,000. At the same time the O'Bannon's radar picked up a fourth set of signals from the north, but there is no evidence that the OTC received this information. The new enemy group was in two sections, one distant 9,000 yards and the other 13,500 yards. The existence of these ships and the presence in the formation of at least one battleship is confirmed by the fact that heavy firing was reported from this area during the action, and by the fact that the San Francisco took a 14-inch shell (a dud) at an angle of 20° with the horizontal. Most of the Japanese vessels were so close to our flagship that all her other damage was caused by shells with very flat trajectories.

___________

18 See appendix, giving the TBS log as kept by the Helena and Portland. There was some evidence of enemy use of TBS for purposes of deception. For example, several operators heard the Pensacola being called. As we have seen, this vessel was not even in the vicinity.

--18--

At this point enemy ships were on both sides of our column, which was in the path of the group containing the first battleship. Suddenly the Japanese illuminated from both right and left and commenced firing.

The time was 0148. The OTC immediately gave the command, "Odd ships fire to starboard, even to port." 19 The guns of the Task Force

__________

19 This order was not literally followed by all ships. The flagship herself, an even-numbered vessel, opened fire to starboard instead of to port.

--19--

opened up, and a free-for-all fight began with little semblance of coordination on either side.

At a conservative estimate, the Japanese could throw three times as much metal per broadside as the American units. They were also in a position to pound our ships from both sides and from ahead. Yet despite initial accuracy of fire, the amount of damage they did was restricted by the fact that they were using bombardment ammunition. They had obviously been expecting to shell our Guadalcanal installations, not to fight an engagement.

The gunfire of the American ships was most effective. Immediately after the illumination by the enemy, which was accompanied, according to some reports, by the dropping of flares from planes, one of the illuminating ships to starboard, probably a Natori light cruiser, came under fire from the San Francisco, Sterett, and other ships. This cruiser was 3,700 yards off the San Francisco's beam. Our flagship illuminated it with her starboard 5-inch battery and fired seven main battery salvos. The Japanese ship blew up within a minute, and other light units to starboard reversed course and fell back toward the central main body, which still had not been sighted by the majority of our force.20

On the port side the Atlanta, Juneau, Helena, Aaron Ward, Barton, Fletcher, Laffey, and O'Bannon opened on illuminating vessels.21The fire of the three light cruisers and the Barton and Fletcher apparently was concentrated on two targets in line. The Atlanta andJuneau blasted a light cruiser, while the Helena, Barton and Fletcher attacked a vessel which was either a heavy or a light cruiser.22Both ships burst into flames. Seeing that her target was out of action, the Fletcher shifted fire to the next ship in line (possibly the target of the Atlanta and Juneau), which she reported as "either a Natori- or Tenryu-class light cruiser." She was joined by the Sterett, which fired 13 salvos. Both the Japanese vessels were seen to sink almost immediately. In the same area "an enemy

___________

20 The Cushing, number one in the column, had opened fire on a destroyer to starboard which may have been one of the "light units."

21 Immediately after illumination and before the enemy commenced firing, the Atlanta opened on an illuminating light cruiser to port, range 1,900 yards, bearing 270° T. Many hits were scored. The Helena opened at 4,200 yards, using radar range and train, and continued fire for 2 minutes, expending 175 rounds. Spot No. 1 reported that almost all shots hit. The port 5-inch battery was on a target slightly to the left of the main battery target at a range of 6,200 yards. Twenty rounds were fired. The Barton, besides using her 5-inch battery, fired 5 torpedoes with unascertained results.

22 The fact that the Helena received two hits at this time, one of which was definitely 8-inch, led that ship to believe that she was engaging a heavy cruiser.

--20--

destroyer exploded" (this may have been one of the cruisers), and two others were seen to be on fire.

The Atlanta, an odd-numbered ship, had been unable to open fire to starboard as ordered because our destroyers were in the way. While she was shooting at the cruiser to port, a division of Japanese destroyers crossed 1,200 yards ahead of her. The forward group of guns was shifted and put 20 shells into the last in line, possibly a Shiguri. It "erupted into flame and disappeared." The after group of guns continued to fire at the enemy cruiser until it ceased firing and sank. A destroyer astern of the latter vessel, which had opened up on the Atlanta, also stopped shooting. At this point the Atlanta had received thirteen 5.5-inch hits and some 3-inch from the light cruiser, mostly in the bridge section, and twelve 5-inch from the destroyers. There were fires forward. As the enemy ceased fire, our cruiser was struck by one or two torpedoes forward on the port side, perhaps from the destroyer to port. All power was lost, except the auxiliary Diesel, and the rudder was jammed left. The ship began to circle back toward the south.

Meanwhile the San Francisco, which had altered course to 280° T., shifted fire from her stricken enemy ship to a "small cruiser or large destroyer further ahead on the starboard bow. [This vessel] was hit with two full main battery salvos and set afire throughout her length."23 The range was 3,300 yards. At about the same time, as nearly as can be judged, a heavy cruiser came up on theAtlanta's port quarter and opened fire at a range of about 3,500 yards, bearing 240° R. The Atlanta reported that 19 hits were scored on her with 8-inch armor-piercing ammunition. Although many of the projectiles failed to explode, her hull was holed several times, and her damaged bridge was shattered. The shells were loaded with green dye, the San Francisco's color. As the first shot struck, Capt. S. P. Jenkins of the Atlanta rushed to the port side to get off torpedoes. When he returned to starboard, Admiral Scott and three officers of his staff had been killed, as well as a large number of other personnel. The foremast collapsed, fires were blazing everywhere, and the Atlanta was dead in the water.

The illuminating ship to port on which the O'Bannon and Aaron Ward opened fire was a Kongo battleship, later identified as the Hiyei. The O'Bannon's guns shot out the searchlight, and several blazes were

____________

23 Action Report of the San Francisco.

--21--

noted on the enemy vessel, probably the result of the combined efforts of the two destroyers. 24

The San Francisco, still heading in a westerly direction, took the Hiyei under fire 2 or 3 minutes later. Range was 2,200 yards and the bearing was about 300° T. Target heading was northeasterly. Many hits were scored at the water line with two salvos. The battleship was seen to be under fire from our van (presumably the O'Bannon) and was burning intensely at the mast. She did not return the flagship's fire. The Cushing was about 1,000 yards to starboard of the Hiyei and saw her "repeatedly hit by ships astern," illuminated as she was by a burning enemy light cruiser. Many shells were seen to strike the foremast and superstructure. The Cushing opened fire with her 20-mm. guns (this also may have been noted aboard the San Francisco) and fired one torpedo from No. 2 mount with unobserved results. Personnel manning this mount were then wounded, so no more torpedoes were launched.

At this time the OTC gave the command over TBS, "Cease firing, our ships." The order did not get through to all vessels, but the San Francisco stopped shooting at the Hiyei. 25

The enemy battleship continued on her course and bore down on our second destroyer, the Laffey. Only by speeding up did the Laffeymanage to cross the enemy's bows with a few feet to spare. Two torpedoes were fired, but the range was so short that there was not time enough for them to arm. The Laffey then shelled the battleship's bridge with all guns that would bear, damaging it severely before she was silenced by a heavy caliber salvo which smashed her own bridge, as well as No. 2 turret, the after fireroom, and the electrical workshop.

____________

24 Aaron Ward, one of the rear destroyers, was firing at a range of 7,000 yards.

25 Zook, L. E., Chief Signalman, one of the 10 survivors of the Juneau, made an interesting suggestion as to the origin of this first cease-fire order. From his station in Battle II, Zook observed that one of the illuminating ships at the outset of the action was a battleship. This vessel began sending short flashes with her searchlight - the Morse error signal - which Zook interpreted as a ruse to convince our ships that she was friendly. While it is conceivable that the OTC might have been momentarily taken in by such a trick, he doubtless would have immediately realized his mistake (the searchlight was much too large to be one of ours) and countermanded his order. Since he did not do so, it seems more likely that he first directed "cease firing" because the Atlanta was reported to be under the fire of friendly guns and later repeated his order because it had not been acted upon.

Furthermore, it is possible that the Hiyei believed that she had illuminated a friendly ship. A captured enemy document dated at Rabaul, 24 April 1942, bears out this thesis. To quote in part: "In the event of any vessel illuminating a friendly vessel the searchlight will immediately be turned off and the following procedure will be carried out: (a) Either with searchlight or signal lamp a series of short flashes will be sent together with the code signal giving the vessel's name ..."

--22--

Meanwhile, at 0152, the Portland's second salvo to starboard blew up a Hibiki destroyer. At this time other enemy ships in the same location began firing torpedoes, one of which struck the damaged Laffey in the fantail as she sheered in a westerly direction.26

At 0153 the O'Bannon turned hard right to avoid ramming the Sterett, which had stopped because of a hit on her port quarter which had jammed her rudder. The Sterett began steering with her engines, while the O'Bannon circled left to rejoin the column astern of the wavering Laffey. The Cushing and Laffey were seen to be receiving many hits from port and starboard. The O'Bannon continued to fire on the Hiyei, which apparently doubled back to the left after passing through our column astern of the Laffey, so that she was bearing down on the Cushing's starboard quarter on a westerly course.

At 0154 the OTC again directed "cease firing." Some ships still did not receive the command. 27 Some continued firing, perhaps because they were sure of their targets. Others obeyed, including the Helena, Fletcher, O'Bannon, and the Portland, which verified the order over TBS. When the O'Bannon opened fire again, she selected a Tenryu cruiser to starboard. The Cushing, having observed theHiyei coming in on her starboard quarter, had turned to the right to get in position to fire torpedoes, although hard hit and losing headway. Six torpedoes were launched at a range of about 1,200 yards. Shortly thereafter three explosions were heard, and at least one large column of water rose on the starboard side of the battleship, which was seen to be under heavy shellfire. The Cushing was then hit by destroyer and cruiser salvos port and starboard which put all her guns out of commission except the 20-mm.

The O'Bannon was now in the lead of our scattered "column," since both the Cushing and Laffey had disappeared to starboard. She was on course 280° T., about 1,800 yards from the Hiyei and coming up on the battleship's starboard quarter. The O'Bannon's radar showed that the three nearby enemy groups had become intermingled, while the two sections of the fourth group were respectively 8,000 and 12,500 yards away. Light enemy units to starboard appeared to be drawing ahead. Our formation had ceased to function as a force. Each ship had become an independent entity faced with the problem of not firing on friendly vessels.

___________

26 Torpedoes also struck the Juneau and the Portland, as will be seen. Possibly all were fired by the destroyers which had crossed ahead of the Cushing and the Atlanta.

27 TBS reception in the destroyers was faulty throughout the engagement.

--23--

At about this time a large enemy ship rolled over and sank 1,500 yards from the Aaron Ward, which was leading our rear destroyers into the melee. This occurrence was also noted by the Helena, which had to stop to keep from colliding with the wreck. The Helena's guns remained silent for several minutes after the OTC's cease firing order, as she had not received permission to open up again.

At 0155 the Barton stopped to avoid collision with a friendly ship and was struck by one and then another torpedo. She broke in two and sank in 10 seconds. Shortly afterward, one of our destroyers passed through the survivors at high speed. Others were injured by depth charges exploding in the vicinity. At about the same time the Fletcher reopened fire on a cruiser astern of her original target to port.

By 0156 the O'Bannon had closed to within 1,200 yards of the Hiyei. There were numerous fires on the battleship, and gunfire had slackened. The O'Bannon fired three torpedoes. There was a tremendous explosion on the enemy ship, which was enveloped in a sheet of flame from bow to stern. Burning particles fell on the destroyer. She fired no more torpedoes and soon swung north, because her course was converging with the Hiyei's. Five burning ships were astern.

At this juncture planes were overhead, but it was impossible to identify them. Torpedoes passed under the Monssen and the Aaron Ward. The Cushing had been heavily hit again, and propulsion was failing. The Portland had been torpedoed, as had the Juneau. The latter ship had been struck on the port side of the forward fireroom after firing only about 25 rounds of 5-inch. Nineteen men were killed. The chief engineer believed that the keel had been snapped. The vessel settled and listed to port, and since all fire control was gone, she began to limp from the scene of action, having shifted steering to aft.

The torpedo that struck the Portland sheered off the inboard screws, flooding Steering Aft and bending out the shell plating on the starboard side to form an extensive right rudder. The ship began circling, and it was found impossible to counteract this with the outboard screws.

After the lull created by the OTC's order to cease fire, the San Francisco again had the Hiyei on her starboard bow, but this time the battleship was steaming on approximately the same heading as our flagship. The Hiyei was illuminating with three lights, two over one. On the San Francisco's starboard quarter was an enemy cruiser which was getting the range. A Japanese destroyer, which had cut across the bow, was passing down the port side with all guns blazing.

--24--

--25--

--26--

--27--

--28--

On hearing of the San Francisco's predicament over TBS, about 0200, the Portland asked the bearing of the battleship. At the same time the Helena requested permission to open fire on targets of her own. The Task Force Commander asked what type of target she had, saying he "wanted the big ones." He then told the Portland to take the battleship along with the San Francisco. The Portland, after completing the first circle to starboard resulting from the torpedo, fired 4 main battery salvos at a range of 4,000 yards, making 10 to 14 hits. The San Francisco also gave the Hiyei everything she had. The American flagship, however, was struck by the enemy cruiser's second salvo, and the Hiyei's third salvo smashed her bridge, killing Admiral Callaghan and mortally wounding Capt. Young and others. Steering and engine control were shifted to Battle II, which was immediately destroyed, and Conn took over.

The San Francisco kept firing at the Hiyei as long as the main battery would bear. Before she was completely knocked out by the battleship, the last remaining gun of her secondary battery set off the depth charges on the stern of the enemy destroyer on the port side. It blew up and was thought to have sunk.

While the San Francisco was dueling with the Japanese battleship, the O'Bannon barely managed to avoid the sinking Laffey and was unable to keep from passing through some of the crew in the water. Life belts were thrown overside. Shortly thereafter the Laffeyblew up, and numerous casualties were caused by descending debris.28

At this time the Helena's radar plot reported 6 ships to starboard which were retiring to the northward. One of them was the light cruiser which was firing on the San Francisco. The Helena's main battery opened on this vessel at 8,800 yards, silencing it with 125 rounds before the San Francisco came into the line of fire on the starboard hand. The secondary battery had simultaneously fired 40 rounds at a destroyer 7,200 yards away.

__________

28 Strenuous measures had failed to save the Laffey. She had incurred most serious damage from shellfire and the torpedo which struck her in the fantail. According to her action report, guns No. 2, No. 3, and No. 4 had been put out of commission, engine spaces were rendered untenable by escaping steam, and the stern had been blown off up to No. 4 turret, destroying propulsion and steering control. Oil was burning, and there was no power or water pressure. Nevertheless, a bucket brigade using empty powder cans, assisted later by a portable gasoline pump, nearly succeeded in bringing fires under control. Eventually the flames blazed up more strongly than ever, and it became necessary to abandon ship. All but a few officers and men were in the water when the after part of the vessel blew up. Among the casualties caused by fragments was her captain, Lt. Comdr. William B. Hank, who was last seen in the water near the bow just before the explosion.

--29--

The Hiyei ceased firing on our flagship after 5 or 6 salvos. The San Francisco had received 15 major caliber hits, as well as numerous others, and 25 separate fires were burning. What had saved her from complete destruction was the enemy's use of bombardment ammunition.29 She was still between 2 Japanese groups, but apparently they were now shooting at each other. The officer of the deck, Lt. Comdr. Bruce McCandless, was conning the damaged ship, while Lt. Comdr. Schonland, who had succeeded to command, continued fighting the fires below. Lt. Comdr. McCandless decided to make his escape around Cape Esperance, but as he continued to head west a large vessel opened up on him,30 and he circled to the eastward, astern of the enemy forces.

After a quarter-hour of battle most of our ships were seriously shot up. The Cushing had received up to 20 hits from cruisers and destroyers and lay helpless. The Laffey had sunk; the Sterett had just been hit in the foremast and had lost SC radar, identification lights, and TBS transmitting antenna; the O'Bannon was slightly damaged. The Atlanta was burning, and the San Francisco andPortland were badly holed. The Helena had suffered minor injury. The Juneau had left the scene of action. The Barton had blown up. Only the Aaron Ward, Monssen, and Fletcher were untouched.

The Aaron Ward did not have long to wait for her share. She passed through what was apparently the entire enemy formation, if such a term could still be used, receiving three 14-inch, two 8-inch, and five smaller hits. However, her officers believed that she sank or helped to sink a Katori-class light cruiser or large destroyer at a range of 3,000 yards. The target was showing fighting lights, white over red over green.

At about 0205 the Monssen launched five torpedoes at the Hiyei, 4,000 yards to the northwest of her. Soon there were two explosions at the target. Five minutes later the Sterett located the Hiyei to port, illuminated by star shells and by a burning vessel to the south. She was seen to be considerably damaged. A full salvo of four torpedoes was fired at a range of 2,000 yards, and the 5-inch battery opened on the battleship's bridge structure. Two of the torpedoes hit and exploded. A few minutes later men were seen going over the side of the Hiyei fore and aft, as if abandoning ship. The Sterett at this time was under heavy cross-fire, and several 5-inch shells struck her bridge.

___________

28 Strenuous measures had failed to save the Laffey. She had incurred most serious damage from shellfire and the torpedo which struck her in the fantail. According to her action report, guns No. 2, No. 3, and No. 4 had been put out of commission, engine spaces were rendered untenable by escaping steam, and the stern had been blown off up to No. 4 turret, destroying propulsion and steering control. Oil was burning, and there was no power or water pressure. Nevertheless, a bucket brigade using empty powder cans, assisted later by a portable gasoline pump, nearly succeeded in bringing fires under control. Eventually the flames blazed up more strongly than ever, and it became necessary to abandon ship. All but a few officers and men were in the water when the after part of the vessel blew up. Among the casualties caused by fragments was her captain, Lt. Comdr. William B. Hank, who was last seen in the water near the bow just before the explosion.

29 The projectiles were loaded with small cylinders, some solid and some hollow. The hollow ones contained incendiary materials.

30 Could this have been the Hiyei again?

--30--

At 0212 the Helena had been unable for some minutes to raise the OTC on the TBS, so she tried to reassemble our scattered units. At 0215 her radar showed that the major portion of the Japanese force was in disorderly retirement. Several reports state that the remaining enemy vessels of the center and left-hand groups were now firing at each other. The Sterett, despite her serious damage, closed a belated Fubuki destroyer and sank her with two torpedoes and two 5-inch salvos at 1,000 yards. The target did not get a chance to fire a single shot. When the Japanese destroyer blew up, the entire area was illuminated, and heavy cross-fire began. Eleven direct hits were received by the Sterett and many near-hits. Ready service powder was set afire, and severe casualties were caused. Only two guns were still serviceable, and the remaining two torpedoes were jammed in their tubes. The engines were still delivering full power, however, and the Sterett managed to retire at flank speed (later reduced to 23 knots.)

Star shells began to burst slightly ahead of the Monssen, apparently coming from the port quarter. The destroyer changed course to about 040° T. at full speed. Another destroyer was sighted close aboard to starboard at a range of 500 to 1,000 yards on course 150° T., either stopped or moving very slowly. The Monssen's starboard 20-mm. guns sprayed the other ship's upper works and were joined by No. 4 gun, firing point blank. Fire was not returned. (This may have been one of our own destroyers.)

Soon the Monssen was again illuminated by star shells to port. She believed them to have been fired by a friendly vessel and flashed recognition lights. Immediately searchlights 2,500 yards away illuminated her and she was hard hit by medium caliber shells. Number 1 gun was put out of action, but the rest of the battery eliminated the searchlight and continued firing until silenced. Steering was lost next, and the destroyer's upper works became a mass of flames. As she had no more guns, torpedoes, or power, abandon ship was ordered. The commanding officer and several others were trapped on the bridge but jumped from the rail to the water, suffering more or less serious injury.

At 0205 the Fletcher had turned south at 35 knots to round up ahead of a Maya cruiser which was proceeding on a southerly course at 20 knots. The Fletcher gradually drew ahead to a position about 6,000 yards on the target's starboard bow. At 0221 the Maya had slowed to 17 knots and was on course 070° T. The Fletcher came left to course 030° T. At

--31--

this time the enemy ship was firing at vessels to the northward which may well have been Japanese. No other action was going on. The Fletcher slowed to 15 knots and fired five torpedoes set for 36 knots. Six minutes later there were two or three explosions at the target. Increasingly heavy detonations were followed by flames. Twenty or 30 minutes later the Maya blew up and "completely disintegrated."

This was the last episode of the action proper.

At 0226 the Helena ordered all ships to form on her and take an easterly course. By 0230 the Cushing was abandoning ship, since her fires were totally out of control.31 The Portland, which was still turning in tight circles at speeds up to 20 knots, asked the Helena for a tow, but this was not considered safe due to the danger of torpedoes. At 0235 the Helena instructed all ships to turn on their fighting lights briefly. Five minutes later she located the San Francisco, although the latter was unable to show lights because they had been shot away. The flagship signaled the news of Admiral Callaghan's death by flashlight, the only means of communication left. TheFletcher joined, and the three ships stood out Sealark Channel. Later they fell in with the Juneau in Indispensable Strait. TheO'Bannon and Sterett retired through Lengo Channel.

When the firing ceased, the Portland observed nine ships burning, only three of these being ours (the Atlanta, Cushing, and Monssen). At 0330 she saw what was thought to he a Nachi-class heavy cruiser blow up.32 A Tenryu light cruiser or large destroyer also exploded.