Fanning I (Destroyer No. 37)

1912-1934

Nathaniel Fanning -- born in Stonington, Connecticut, on 31 May 1755 to Gilbert Fanning, a merchant, and Hulda Palmer -- likely enjoyed a familiarity with the sea when hostilities commenced between the break-away American colonists and the British crown. After the British bombarded Stonington in August 1775, Nathaniel decided that the colonists would win the escalating conflict and took up the American cause.

After two cruises on board American letters of marque, Fanning embarked as prize-master on board the privateer brig Angelica. Under the command of William Dennis, the ship departed Boston on 26 May 1778. Five days later, on Nathaniel’s twenty-third birthday, lookouts spotted a vessel they supposed to be a Jamaica merchantman and closed. After approaching the vessel, Angelica’s crew learned with a start that it was in fact a British warship. The Americans attempted to beat a hasty retreat but the British frigate Andromeda captured Angelica and took her crew prisoner. The crew endured a difficult Atlantic crossing confined in the hull of the frigate under orders of General William Howe, then returning from America. After arriving in England, the British held the crew in Forton prison outside of Portsmouth, England. Fanning remained imprisoned there until 2 June 1779 when he was exchanged and transported to France.

Arriving in France he continued by land to L’Orient and arrived on 27 June 1779. In that city he encountered American Commodore John Paul Jones who invited the experienced seaman to join the crew of the frigate Bonhomme Richard. The vessel departed L’Orient on 14 August 1779, planning on a short cruise in the English Channel before returning to the United States. The frigate preyed on British shipping in the English Channel and the North Sea for over a month, capturing, ransoming, or destroying several vessels.

On 22 September 1779, the American squadron was chasing a small convoy when Jones spotted a much larger British convoy –merchantmen guarded by a frigate and a sloop -- off the coast of Yorkshire, England. As Jones’s squadron closed, Midshipman Fanning led a party of fifteen marines and four sailors into Bonhomme Richard’s main top to prepare to engage the enemy with an array of small arms. The commodore ordered the men in the tops to engage the tops of the approaching British frigate, later identified as Serapis. Fanning and his party were in place when Bonhomme Richard’s guns unleashed the first shots of the engagement.

The British vessel early made use of her superior firepower and maneuverability and gained an advantage on her adversary causing significant damage to the American ship and death among her crew. Bonhomme Richard sought to neutralize that advantage by closing on Serapis and boarding her. As the vessels maneuvered close aboard, Midshipman Fanning led his men in a murderous fire on the enemy’s tops. The frigates soon became entangled and Jones ordered his crew to grapple the enemy ship and prepare to board.

As the crews of two warships were locked in gunnery duels below, Fanning’s top-men exchanged fire with their counterparts aloft. After gunfire killed or wounded the majority of his men, Fanning clambered down and gathered a new party. The officer returned and the Americans silenced the final British sharpshooter in the rigging of Serapis approximately forty minutes into the battle. The Americans in the tops then focused their fire on the enemy decks. The American sailors and marines pressed their advantage, and took possession of Serapis’s vacant fighting tops by shinnying across the vessels’ interlocked yardarms. From this position the Americans effectively commanded the entire deck of the enemy warship, firing and dropping grenades at will on any Jack Tar that emerged from below.

The actions of Nathaniel Fanning and his top-men proved crucial to the American victory. With fires raging in the rigging, the hold flooding, and British captives loose below deck, Bonhomme Richard looked nothing like a victorious man-of-war. The men in the tops, however, pinned down and harassed the British crew for hours. Late in the fighting, one of the top-men delivered a serious blow to Serapis by dropping a grenade through an open hatch that set off gunpowder below decks. The resulting explosion decimated several gun crews. With the other vessels in the American squadron bringing their guns to bear on Serapis, the British commander capitulated after four hours of battle, conceding the victory to the sinking Bonhomme Richard. After the American frigate sank, Fanning and the crew of Bonhomme Richard sailed to Texel, United Provinces, on board Serapis.

Commodore Jones applauded Fanning’s actions writing Congress, “His bravery…in the action with the Serapis… will, I hope, recommend him to the notice of Congress in the line of promotion.” According to Commodore Jones “. . . [Fanning] was one cause among the prominent in obtaining the victory." After a cruise off Spain with Jones in the frigate Alliance, Fanning separated from the Commodore at L’Orient. The young sailor parlayed his growing reputation into a position as second in command in the French privateer lugger Count de Guichen, being entrusted with that ship’s operational decisions. The vessel departed Morlaix on 23 March 1781 and captured a British privateer the following day. He captured or ransomed several other ships and their crews before the British frigate Aurora caught up with her and forced Fanning’s vessel to surrender. The British exchanged him six weeks later.

Returning to Morlaix, he planned to return to Massachusetts with his prize money and sailed on board a French brigantine privateer on 12 July 1781. Again his homecoming was ruined, this time by a gale that wrecked the vessel on an island off the coast of France. Having escaped with his life but with all of his possessions and prize money lost, the hard-luck sailor “came to this determination, never to attempt again to cross the vast Atlantic Ocean until the god of war had ceased to waste human blood in the western world.” He enlisted with the same French captain that he earlier served under in a privateer cutter Eclipse of eighteen guns.

Eclipse began her cruise in early December 1781, capturing and ransoming several merchant vessels and continued operating successfully against British shipping until early March. The vessel underwent refitting at Dunkerque [Dunkirk], France until May. The owners of Eclipse offered Fanning the command, which he accepted, but he was not content to sit idle while his ship underwent a refit. In March 1782, he boldly crossed the channel and visited London on a clandestine errand to redeem, personally, the ransom notes collected on his previous cruise. After completing his task and gathering intelligence overheard in British coffee houses, he travelled to Dunkerque only to return immediately to London. The American’s second errand to the enemy capital was to deliver letters from the French Court to members of parliament sympathetic to the American cause. After completing his task and touring England, even viewing the King in person, Captain Fanning returned to Dunkerque in time to command Eclipse against His Majesty’s shipping.

Fanning took command of Eclipse on 12 May 1782 at the young age of 27. He fit her for a cruise around the British Isles and had her painted to appear as a Royal Navy cutter and outfitted his men like British sailors. He styled himself as “Captain John Dyon,” of His Majesty’s Cutter Surprize, to avoid detection, sailing in June 1782 but was soon trapped in the Orkney Islands when two superior British vessels unknowingly blocked his access to open water. After an audacious attempt to ransom a nearby village failed, Eclipse bribed a pilot and escaped without alarming the two British warships. He captured several British merchantmen and outran pursuing warships. His crew prevailed in a bloody boarding action against the armed merchantman Lovely Lass and were rewarded with a hold full of valuable West Indian goods. He returned to L’Orient with his spoils and Eclipse underwent repairs.

In August 1782 the cutter returned to sea quickly capturing two prizes. He was chased by the British fourth rate Jupiter. The ship-of-the-line overhauled Eclipse before Captain Fanning brazenly escaped as a British boarding party was approaching the vessel. He personally took the helm during the escape while ordering his men to lie flat on deck to avoid enemy fire. After several hours on the run the fleeing cutter spotted an entire British fleet in her path. Captain Fanning ordered his vessel, still disguised as a British cutter, through the heart of the force. He brusquely answered hails from massive ships-of-the-line as Captain Dyon and rushed through the gathered warships. Before the British could realize their mistake and maneuver their plodding vessels to fire, Fanning was clear of their threat. Jupiter continued pursuit, however, and wounded several of Eclipse’s crew, including Fanning, in the nocturnal chase. A favorable change in wind, however, allowed the French privateer to shed her stubborn adversary and slip off into the night.

Two days after that narrow escape, the privateer spotted approaching sails and broke the French ensign preparing for battle. Her opponent, the British Lord Howe, transporting a regiment of British infantry from Ireland, engaged Eclipse with her twelve-gun broadside. Fanning’s vessel soon outmaneuvered and raked her foe. Although wounded in the leg by a musket ball, Fanning remained at his station on the deck issuing orders. Laying Eclipse alongside Lord Howe, Fanning’s men leapt on board the English vessel and engaged in a bloody fight against a superior force of British sailors and soldiers. After significant losses to both sides, the French privateer proved victorious, but was forced to abandon her prize when a British frigate closed. Eclipse made off with the crew and ensign of Lord Howe and out-sailed the frigate before arriving at Dunkerque.

Word of Fanning’s exploits impressed officials in France who commissioned him a lieutenant in the French Navy in October 1782. On the 23rd of that month, Lieutenant Fanning was acting captain of the small cutter Ranger when she stood out for the coast of southeastern England. Again the officer displayed his audacity by disguising his privateer as an English coasting vessel and sailing alongside an armed British convoy for three days, waiting for an opportunity to strike. The moment presented itself when the convoy dispersed in the dark to avoid hazardous weather. In the confusion, Ranger picked off three surprised privateers and took them as prizes under the noses of their escorts. Fanning’s success greatly handicapped Ranger, however, by depriving the crew of experienced seamen after they were assigned to man the prizes. The depleted and inexperienced skeleton crew thus had no hopes of escaping when a British cutter closed on the French vessel at sunrise. The enemy cutter overhauled Ranger at 2:00 p.m. and Fanning found himself a prisoner of the British for the third time. The British exchanged him quickly and he returned to Dunkerque only seventeen days after departing, finding his prizes waiting for him.

Only five days after returning to France, Fanning departed on another cruise in command of a small lugger. After only two days, a British frigate spotted the French privateer and overhauled her after a ten-hour chase, and Fanning entered captivity for the fourth time, on that occasion being roughly treated on board the frigate for six weeks before she in turn was captured by a French fleet off the coast of France. Fanning endeavored to prepare a brig for another cruise before the American commissioners reached a rumored peace with Great Britain. As the vessel finished her final preparations, notification of a preliminary peace reached Dunkerque on 30 December 1782. After months touring France and securing his wartime earnings, Fanning embarked on board a French vessel on 30 September. He disembarked at New York in mid-November and finally returned to the U.S. after an adventurous time abroad.

After over 21 years, Fanning returned to naval service of the U.S. and was commissioned lieutenant on 4 December 1804. He initially supervised the construction of Gunboat No. 9 at Charleston S.C., then, on 6 May 1805, obtained command of Gunboat No. 1 as she operated between Savannah, Georgia, and Georgetown, S.C. Fanning attempted to prepare his ship for deployment to the Mediterranean to wage war against the Barbary Pirates but the vessel proved not strong enough for a trans-Atlantic voyage, instead operating out of Charleston, S.C., where Fanning fell sick and died of yellow fever on 30 September 1805.

I

(Destroyer No. 37: displacement 742 (standard); length 293'10½", beam 26'1½", draft 8'4¼"(mean), speed 29.99 knots; complement 91; armament 5 3-inch guns, 2 .30-caliber machine guns, 6 18-inch torpedo tubes; class Paulding)

The first Fanning (Destroyer No. 37) was laid down on 6 December 1910 at Newport News, Va., by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.; launched on 11 January 1912 and sponsored by Mrs. Kenneth McAlpine, wife of Capt. Kenneth McAlpine, Inspector of Machinery for the U.S. Navy at Newport News.

Accepted by the Navy on 20 June 1912, Fanning was commissioned at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., on 21 June 1912, Ens. John Borland in command.

Attached to the Fifth Division of the Atlantic Fleet’s Destroyer Force, Fanning spent her early years engaged in trial runs and training, with her crew learning ship handling. During the course of those evolutions, the new destroyer ranged from the waters off the eastern seaboard of the U.S. to the Caribbean Sea. She also participated in the Naval Review held at New York City in October 1912. Operating with the Destroyer Flotilla, she practiced gunnery and torpedo firing. She conducted fleet problems out of her base at Norfolk during 1915.

Clearing Norfolk on 8 January 1916, Fanning reached Culebra, Puerto Rico, a week later, on the 15th, to carry out winter maneuvers in the Caribbean. In addition, she carried out reconnaissance of the coasts of San Domingo and Haiti. Eventually, she stood out of Guantanamo Bay on 9 April, and conducted a tactical problem while en route to Boston, Mass., capped by a pause at Hampton Roads (13-15 April).

Standing in to the Boston Navy Yard on 16 April 1916, Fanning remained in yard hands until 2 June, when she sailed for Portland, Maine, reaching her destination later the same day. In accordance with orders of the Commander, Destroyer Flotilla, the warship then carried out a reconnaissance of the coast of Maine, after which she departed Portland on 28 June for Newport, R. I., arriving in those waters the following day to begin participation in a series of tactical problems there and in Gardiner’s Bay, Long Island. Eventually, Fanning completed her participation in those evolutions on 30 August, clearing Newport for Hampton Roads, whence she conducted gunnery practice for the bulk of September, operations punctuated by forming part of the force convoying the German auxiliary cruisers Prinz Eitel Friedrich and Kronprinz Wilhelm, that had stood in to Newport News the previous spring and been interned there, on their voyages to Philadelphia.

Standing in to Newport harbor on 1 October 1916, Fanning conducted torpedo proving practice daily over the ensuing days. Less than a week later, on 7 October, the German submarine U-53 (Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, commanding) entered Newport. Confronted with the prospect of internment if he and his command tarried too long in port, Rose took his boat to sea, and soon, with dramatic suddenness, embarked on sinking belligerent merchant ships off the Nantucket Lightship. Destroyers based on Newport immediately sortied to rescue survivors when word reached port of U-53’s activities.

At 1:30 p.m. on 8 October 1916, Fanning cast off and stood out to sea to proceed to those waters, and reached the scene at 5:30, the destroyer sighting U-53 and the Dutch steamer Blommersdijk hove-to nearby about a mile to the east, and the British passenger ship Stephano three miles to the northeastward. While other destroyers attended to the surviving passengers and crew, Fanning stood near the lightship to receive six fishermen, part of the crew of the U.S. fishing vessel Victor & Ethan that had been sunk in collision with a steamship in the fog. She also took five dories in tow, and that night conducted a search for survivors of the steamship Kingston.

Returning to Newport on 9 October 1916, Fanning transferred the six rescued Victor & Ethan mariners and three dories (two had sunk in the interim) to Jenkins (Destroyer No. 42) (which had picked up the master and additional crewmen of Victor & Ethan), after which Fanning steamed to Melville, thence to Gardiner’s Bay for torpedo practice. Soon thereafter, in the wake of U-53’s sudden and dramatic appearance off the eastern seaboard, Fanning reconnoitered the coast near Newport as well as New Haven, Conn., to ensure that German submarines were not using those coastlines as bases (12-14 October).

Following an experimental oiling at sea, replenishing her bunkers from Jason (Fuel Ship No. 12) (14-25 October 1916), Fanning resumed torpedo practice in the waters of Menemsha Bight, after which she put in to Newport. Clearing that place on 30 October, the warship put in to the Boston Navy Yard later the same day to begin an overhaul that lasted into the New Year.

Fanning cleared Boston on 8 January 1917 and set course for the Caribbean, putting in to Guantanamo Bay on the 12th. She conducted maneuvers with the fleet until 5 February, after which she carried out gunnery exercises. Following a period where she served as a special duty mail ship for those vessels conducting exercises in those waters (11 February – 21 March), she stood out of Guantanamo Bay in formation with the fleet on 23 March, bound for Hampton Roads. She put in to the Norfolk Navy Yard for a machinery overhaul on the 27th.

Shifting to the entrance of the York River soon thereafter, however, as tensions with Germany escalated over unconditional submarine warfare, Fanning lay anchored there on 6 April 1917, dragging the bottom for a lost anchor, Lt. Arthur S. Carpender, her commanding officer, received orders incident to the U.S. declaring war on Germany that day, from Pennsylvania (Battleship No. 38) organizing the Patrol Force and ordering the destroyer to report to Rear Adm. Henry B. Wilson, its commander, who wore his flag in Olympia (Cruiser No. 6).

Carpender complied with his orders on the 8th, but reported to Rear Adm. Wilson that he [Carpender] “believed it necessary that [the ship] should proceed to her home yard for docking and overhaul before being assigned to patrol [duty.]” He pointed out that Fanning “had steamed about 13,000 miles between the first part of January [1917] and the present…” Fanning’s January departure from Boston had been carried out despite the fact that items of work remained to be accomplished [the original completion date having been 25 February].

Prior to the abbreviated overhaul, the ship had been “detailed to accompany the fleet south” and from that time forward “only such work as was necessary to fit the vessel for sea” had been performed. Furthermore, Carpender reported broken or missing strainers and a rudder in bad condition, and that the ship had not been docked in the wake of two groundings in Cuban waters. In addition, the destroyer’s commanding officer related that the Philadelphia Navy Yard had issued job orders for a number of approved repairs and had transferred several incomplete orders to the Boston Navy Yard. On 12 April, Rear Adm. Wilson ordered Fanning to proceed to Philadelphia to expedite repairs. Underway immediately, the destroyer reached the navy yard the next day. Within a fortnight, on 1 May, she received orders to prepare for “distant service.”

Emerging from yard hands on 7 June 1917, she cleared the Philadelphia Navy Yard that day, and reached the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 7 June. On 14 June, Fanning served as part of the escort for the first American Expeditionary Force (AEF) convoy, stood down the harbor and down the Ambrose Channel. Clearing the channel at 1:30 p.m., she took position to escort Group No. 2 of the convoy, formed around Momis, Antilles and Lenape, carrying troops of the First Expeditionary Forces to sail for France.

Birmingham (Cruiser No. 2) served as the escort flagship, while the armed yacht Aphrodite (S. P. 135), Fanning, Burrows (Destroyer No. 29) and Lamson (Destroyer No. 18) protected the vital transports as well. Ordered to proceed ahead at 18 knots on 17 June 1917, to join Group No. 1 at a designated rendezvous, to replace the armed yacht Corsair (S. P. 159), which had ordered back to replace her in Group No. 2, Fanning sighted Group No. 1 at 5:10 a.m. the next morning [18 June]. Fanning thus joined Seattle (Armored Cruiser No. 11), and Wilkes (Destroyer No. 67) and Terry (Destroyer No. 25) in shepherding Tenadores, Saratoga, Havana, and Pastores, as well as the troop transport DeKalb (Id. No. 3010) – a ship that Fanning had encountered under different colors the previous autumn as the auxiliary cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich. On 20 June, Fanning oiled from Maumee (Fuel Ship No. 14).

At 10:30 p.m. on 22 June 1917, after DeKalb’s fire control officer reported “looks like the wake of a torpedo crossing our bow,” the troop transport fired the first of two shots to port that landed about 1,000 yards ahead of Fanning, which rang down 18 knots to close the spot where the shell had landed. DeKalb, meanwhile, sounded six blasts of the siren to warn the convoy. Fanning passed over two broad phosphorescent streaks – the first at 10:46 p.m. and the second at 10:50 – that officers identified as that which “could only have been made by submarines or torpedoes.” Later information, however, revealed no enemy boats in the vicinity [confirmed post-war by a search of German Admiralty records].

The following morning [23 June 1917], U.S. ships based on Queenstown [Cobh], Ireland, rendezvoused with the convoy, Cushing (Destroyer No. 55), Conyngham (Destroyer No. 58), Ericsson (Destroyer No. 56), O’Brien (Destroyer No. 51), Winslow (Destroyer No. 53) and Jacob Jones (Destroyer No. 61) joined as the Eastern Escort. Fanning guarded the convoy’s rear (23-25 June); Group No.1 safely reached the destination of St. Nazaire on 26 June 1917; Group No. 2 steamed in at 5:10 a.m. on the 27th and Group No. 3 at 11:30 a.m. on the 28th.

On Independence Day 1917, Fanning cleared St. Nazaire with Shaw (Destroyer No. 68), Parker (Destroyer No. 48), Burrows and Ammen (Destroyer No. 35), and Wilkes (Destroyer No. 67), the first five ships setting course for Queenstown and the last for Portsmouth, England. Fanning and her consorts stood in to Queenstown harbor during the forenoon watch on 5 July. Four days later, the ship “landed all unnecessary stores,” while workmen fitted her with depth charges “and chutes for releasing same,” in addition to splinter mattresses, preparing her for operations in European Waters.

Departing Queenstown on her first patrol on 10 July 1917, Fanning sighted a “vessel to port which gave every appearance of being a submarine on the surface” a little over three hours into the mid watch [3:04 a.m.] on 11 July. Fanning gave chase at full speed but after one shot discovered her quarry to be a British steam trawler. A sketch of the ship’s wartime history concludes that incident with the words: “No damage done.”

Fanning sighted a small boat ahead at 10:19 a.m. on 13 July 1917 and closed a lifeboat six minutes later, picking up 13 survivors from the Greek steamship Charilaos Tricoupis, that had been torpedoed without warning by U-58 (Kapitänleutnant Karl Scherb) at 8:15 a.m. that morning while en route from Dakar to Sligo, Ireland, with a cargo of maize. At 10:40 a.m., the destroyer came across two more lifeboats from the same vessel, bringing on board 10 additional sailors. Transporting them to Bantry, Ireland, Fanning put them ashore there later that day.

A little over a week later, on 21 July 1917, while on course for Fastnet as escort for the British steamship Aurania, Fanning was missed by a torpedo that came from off her port quarter and passed beneath her engine room. Increasing speed to 22 knots, the destroyer turned toward where the weapon had come from, circling the area astern of the convoy but seeing no sign of a submarine.

Fanning reprised the role of rescuer when she sighted two sail at 7:56 a.m. on 28 July 1917. Closing, she brought on board the survivors she found in the two boats at 8:30 a.m., then sighted another small boat at 9:08 a.m. Soon thereafter, at 9:45, she rescued the last of what she would record as 57 men – all hands – of the British turret hull steamer Belle of England, torpedoed at 1:05 p.m. the day before [27 July] by U-95 (Kapitänleutnant Athalwin Prinz) as the merchantman had been en route from Cartagena to England with a cargo of iron ore.

Sighting a submarine on 2 August 1917 on her starboard bow at the range of 300 yards, Fanning gave chase to the U-boat as she moved south at about 10 knots. The destroyer increased speed to 22 knots to attain a position to attack, but the unterseeboote submerged, evidently having seen her pursuer. Thwarted in her effort to determine the enemy’s submerged course by the choppy sea, Fanning found no further sign of her quarry, and she was never in a position to drop a depth charge.

Following a refit at the Cammell Laird yard, Birkenhead, England (16-22 September 1917), Fanning sailed soon thereafter to return to Queenstown. At 7:20 a.m. on 25 September, she received a signal from the Coningbeg Light Ship concerning a shipwrecked crew. Consequently, at 7:45 a.m. that day the destroyer embarked Edward Purcer and two other men from the 101-ton British schooner Mary Grace who had been waiting for passage to an Irish port. Mary Grace had been en route from Youghal, Ireland, to Swansea, England, with about 60 tons of lumber when a submarine sank her 25 miles south of Mine Head at 7:00 p.m. on 24 September. The following morning [25 September] at 9:40 a.m., Fanning sighted a surfaced submarine on the surface at 12,000 yards, 23 miles south by southeast of Mine Head, and pursued her, but her quarry submerged. The destroyer dropped a depth charge after arriving at the spot of the sighting with “no apparent results.”

While Fanning was escorting Maumee on 7 October 1917 in “very thick” weather, the fuel ship spotted a submarine on the port bow 2,500 yards away. The destroyer plowed through the rough sea at 16 knots but proved unable to close on her target before she slipped below, then dropped a depth charge on the estimated spot of submergence “without visible results.”

Fanning was escorting convoy H. S. 12 on 18 October 1917, which included in its company the British steamship Madura – bound, ultimately, for France with a varied cargo that ranged from locomotives to lumber – that fell behind the other ships. U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen) torpedoed the straggler on her port side without warning and she settled rapidly by the head. Fanning took two survivors on board (HMS Defender took the rest), and stood by the vessel, waiting for tugs, summoned to the scene, and assistance to arrive. At 12:38 p.m., lookouts spotted a submarine on the surface, and the destroyer gave chase and after the submarine submerged, dropped a depth charge on a spot of disturbed water. The attack proved ineffective, however, and U-62 escaped to fight again. Fanning returned to the sinking steamship in time to witness her final plunge as Madura sank in about 30 seconds.

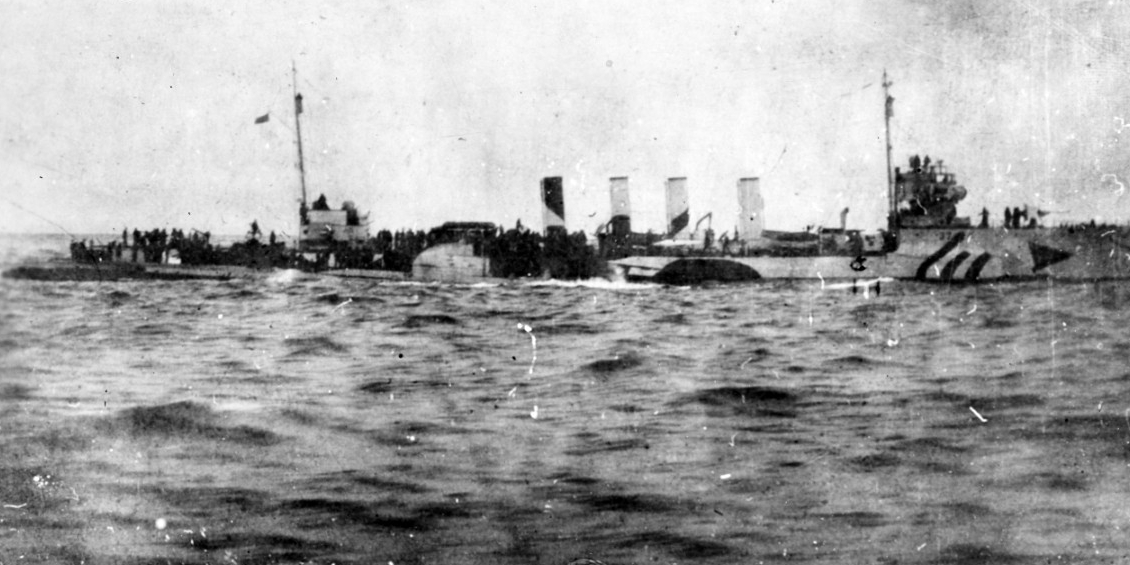

Almost exactly a month later, however, on 17 November 1917, Fanning was escorting convoy O.Q. 20 in waters south of Ireland. She had been at sea for five hours when, at 4:20 p.m., sharp-eyed Cox. Daniel D. Loomis, the bridge lookout, spotted a periscope – that projected a mere foot from the water – three points on the port bow, 400 yards away. U-58 (Kapitänleutnant Gustav Amberger) crossed the destroyer’s bow and Fanning gave chase, with Lt. Walter O. Henry, the officer of the deck (OOD), ringing down full speed and swinging the ship into position over her adversary.

After dropping a solitary depth charge that wrecked U-58’s motors, diving gear and oil leads, the boat plunging to 200 feet before blowing ballast for a hurried ascent. Fanning spotted the submarine come to the surface, conning tower exposed. Escort flagship Nicholson (Destroyer No. 52) dropped another charge close aboard the sub and scored another hit and opened fire with her after gun. Fanning followed suit and scored several hits on the German boat. After the third report of one of Fanning’s 3-inchers the submarine hatch flew open and life-belted German sailors quickly clambered onto the deck with their hands in the air.

At 4:28 p.m., Fanning maneuvered alongside the foundering U-58 while the latter’s crew – some of whom showed signs of exhaustion – began to swim toward the destroyer. The destroyermen threw lines to the survivors but Chief Engineer Franz Glinder proved too weak to hold the line. Although CPhM Elizer Hartwell and Cox. Francis G. Connor jumped into the icy seas in an attempt to assist him, Glinder drowned before he could be hauled on board – attempts to resuscitate him proved fruitless. After retrieving the submariners Fanning counted four officers, including Kapitänleutnant Amberger, who had only been in command of U-58 for a little over a fortnight, and thirty-five men as prisoners. Interviews with the German officers established that Fanning’s depth charge significantly damaged the submarine’s machinery and forced her to the surface. While the U.S. destroyermen kept the survivors under strict guard, they treated the German sailors with respect and dignity, giving them hot coffee and sandwiches, and tobacco. Lt. Carpender conducted the service as they committed the remains of Chief Engineer Glinder to the deep. When the Germans disembarked at Queenstown to begin their journey to captivity in the U.S., they showed their appreciation by cheering Fanning as they left the ship.

Fanning’s victory prompted celebrations. On 19 November 1917, Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Coast of Ireland, came on board and read a congratulatory cablegram from the Admiralty addressed to the ship. Capt. Joel R. P. Pringle, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Destroyer Flotilla operating in European Waters, also visited, reading similar laudatory cables from Adm. William S. Benson, the Chief of Naval Operations, and Vice Adm. William S. Sims, the Force Commander. Adm. Bayly authorized the Fanning’s crew to paint a coveted white star on her forward funnel to proclaim her victory over U-58. For their part in the victory Lt. Carpender received the Distinguished Service Medal, Lt. Henry and Cox. Loomis the Navy Cross. War did not permit any resting on laurels so arduously won, however, and for Fanning it was back to work, departing Queenstown on 20 November to escort convoy O.Q. 21, in company with Allen (Destroyer No. 66) (flag), Porter (Destroyer No. 59), Winslow (Destroyer No. 53), Trippe (Destroyer No. 33) and Sterett (Destroyer No. 27)

Two days into the New Year 1918, Fanning cleared Queenstown with Wilkes, Wainwright (Destroyer No. 62), McDougal (Destroyer No. 54), Sterett, Paulding (Destroyer No. 22) and O’Brien and HMS Bluebell to meet an inbound convoy. At 1:55 p.m., the watch sighted a wake that included oil bubbles emanating from within. Fanning traced the wake at full speed and dropped a depth charge ahead of the wake, noticing “an unusual amount of oil” bubbling to the surface. A fortnight later [16 January 1918], Fanning was escorting a mercantile convoy with Wilkes (flag), Wainwright, Benham (Destroyer No. 49) and Winslow, as well as HMS Jessamine and HMS Viola during which passage Benham dropped depth charges at 1:14 p.m. and 1:23 p.m. with no discernable results.

Following a drydocking at Birkenhead (15-22 February 1918), Fanning did not encounter the undersea enemy for almost three months. The British steamship Baron Ailsa was being escorted by Fanning at 6:06 a.m. on 9 May, when a torpedo from UB-77 (Oberleutnant zur See Friedrich Trager) sank her. The destroyer put her rudder hard left and although she began dropping depth charges at ten second intervals for a total of 26, she observed no results. She put two rafts over the side and launched her whaleboat to pick up survivors but before she could do so she spotted a periscope 3,000 yards astern. She rang down full speed and dropped one depth charge. After nearly thirty minutes the destroyer returned and the whaleboat rescued 18 survivors and retrieved one corpse. Aided by a blimp and two British patrol vessels, Fanning continued to patrol amidst the wreckage until 4:00 p.m., when she then set course for Milford Haven, arriving there at 5:45 p.m. where she transferred the 18 survivors and one body to the drifter Panopia which then landed them at Milford Haven. Fanning then set course for Queenstown, arriving there the enxt morning. Not long afterward, UB-77 was herself torpedoed and sunk, by a British submarine, on 12 May, with Oberleutnant zur See Trager and 34 of his 38-man crew lost with the boat.

Three days later [12 May 1918], while operating with Balch (Destroyer No. 50) and Cummings (Destroyer No. 44) and the British destroyers HMS Achates, HMS Lawford, and HMS Michael, Fanning saw more action when a submarine unsuccessfully attacked the trailing ship in her convoy. Balch and Zinnia dropped depth charges, while Fanning went to full speed to cover the front of the convoy and Cummings took Balch’s place. At 2:07 p.m., while turning with right rudder, Fanning spotted a suspicious object on the starboard beam, about 500 yards distant. She increased speed to 25 knots. The unterseeboote submerged and Fanning dropped one depth charge from the starboard chute and fired another from her starboard thrower, both without results.

After sighting a heavy oil slick at 7:20 a.m. on 14 May 1918 Fanning dropped nine depth charges on a heavy oil slick that officers interpreted as a possible submerged U-boat, but “without apparent results.” Four days later [18 May] the cargo ship Newport News spotted a submarine at 3:30 p.m. and Fanning and Sterett dropped depth charges with the former expending sixteen. On 21 May, while teamed again with Sterett, convoying the Naval Overseas Transportation Service (NOTS) collier Besoeki (Id. No. 2534), Old Colony (Id. No. 1254) and the steamship War Angler, Sterett dropped a torch pot at 11:50 p.m. and reversed course at high speed, with Fanning following, the latter dropping ten depth charges with no discernable results. While escorting a convoy in company with O’Brien on 26 May, she dropped 26 depth charges after seeing a submarine surface and quickly submerge 9,000 yards away. She concluded her active May by joining Sterett and Cushing on the 31st in proceeding to the scene of the loss of the troop transport President Lincoln – torpedoed and sunk by U-90 (Kapitänleutnant Walter Remy) earlier that day – and depth charging a suspected submarine while en route, recording no results after she expended ten more charges. Arriving on the scene of President Lincoln’s loss, the destroyers investigated the boats and rafts in the vicinity but all living survivors by that point had already been rescued by other ships. Fanning returned to port on 2 June in company with Cushing, the latter having rescued survivors from the British steamship Begum, which had been torpedoed and sunk by U-90 on 29 May (two days before she had sunk President Lincoln), en route.

On 4 June 1918, Fanning escorted a convoy to Brest, France, arriving there on the 8th, and would operate thence into the autumn. Fanning barely avoided an attack at 6:58 a.m. on 5 August 1918, when a torpedo ran under her stern. After dodging the shot, Fanning turned hard right and searched for her attacker within the confines of the convoy. Fifteen minutes later, she dropped 14 depth charges on a suspicious oil spot and 10 more later on a zig-zagging oil wake, attacks that proved unsuccessful.

On 8 August 1918, Fanning assisted the survivors of the NOTS cargo ship Westward Ho (Id. No. 3098), that had been torpedoed by U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen, whom Fanning had encountered ten months earlier), recovering two lifeboats with 25 survivors. Two British tugs and the mine sweeper Concord (S. P. 993), however, saved Westward Ho and brought her into Brest. Fanning’s lifesaving duties continued that evening when she rescued 74 survivors from the French Cruiser Dupetit-thouars, which had also been torpedoed by U-62 the day before [7 August]. Fanning continued her escort duty with the 99 recovered men still on board.

Tucker (Destroyer No. 57) signaled a submarine ahead on 9 August 1918, and Fanning joined her in the hunt. She eventually sighted a wake 300 yards ahead, and dropped six charges on the wake without result. The next day, however [10 August], Fanning–with the U.S. and French sailors picked up on 8 August still passengers – responded to the report of a sighted submarine. At 3:08 p.m., a torpedo passed under the bow close aboard, targeting one of the convoyed ships, but missed both Fanning and its intended target. Two minutes later, Fanning’s forward lookout spotted a periscope on the port bow and the ship pursued, dropping fourteen depth charges in the process. The submarine’s superior turning radius, however, allowed her to escape despite her wake being clearly visible by the crew. Joined by Ericsson (Destroyer No. 56) and Roe (Destroyer No. 24), Fanning dropped 17 depth charges on 11 August after sighting a periscope. On 12 August, the destroyer returned to Brest and disembarked the survivors of Westward Ho and Dupetit-thouars.

On 28 August 1918, Fanning suffered dents, loosened rivets, and a small leak on the berth deck when a water barge being towed by the tug Cricciceth (BM1c F. B. Hale in charge), struck her twice on the port side while she lay moored at Brest at 6:37 p.m. A little less than a month later, on the night of 24-25 September, the destroyer grounded, losing her rudder in the process and requiring being laid-up for repairs of the rudder and one shaft. She resumed active service on 22 October, but less than a month later, on 11 November, the Armistice ended the World War. Fanning witnessed the arrival at Brest of President Woodrow Wilson on 13 December in the troop transport George Washington (Id. No. 3018), and the destroyer passed in review with other U.S. warships.

Following a drydocking at Brest (30 January-7 March 1919), Fanning embarked 17 naval officers and 123 enlisted men [submariners] for transportation to Plymouth. She sailed at 7:29 a.m. on 11 March for England, and reached her destination at 4:00 p.m. The next day [12 March], she embarked two officers and two enlisted men, and took on board 10 bags of mail, and made the cross-channel passage back to Brest.

A little over a week later [20 March 1919], Fanning cleared Brest for the last time at 8:42 a.m. She joined a goodly company of ships at 10:42 a.m. – Warrington (Destroyer No. 30), the tender Hannibal, a trio of tugs, and 33 U.S. submarine chasers. They set course for Lisbon, Portugal, reaching their destination on 24th. Fanning conducted a brief round-trip to Gibraltar (29-30 March), loading ordnance stores for delivery to Hannibal, as well as mail for the ships waiting at Lisbon, and returned to Lisbon at 3:47 p.m. on 31 March. The destroyer then set course for the Azores on 6 April, this time in company with Warrington, the destroyer tender Leonidas, five tugs, and 41 submarine chasers, standing in to Punta Delgada on the 10th.

After almost a fortnight layover in the Azores, Fanning sailed for Bermuda on 22 April 1919 in company with Warrington, Leonidas, the fuel ship Arethusa, three tugs and 41 submarine chasers, making arrival on 2 May. Fanning sailed for Charleston, S.C., the following day [3 May], reaching her destination three days later. She remained at Charleston for over three months, sailing for the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 25 August, and arriving there later the same day where, ultimately, on 24 November 1919, her remaining men were transferred to Henley (Destroyer No. 39) that was being employed as a barracks ship, and Fanning was decommissioned and turned over to the commandant of the yard.

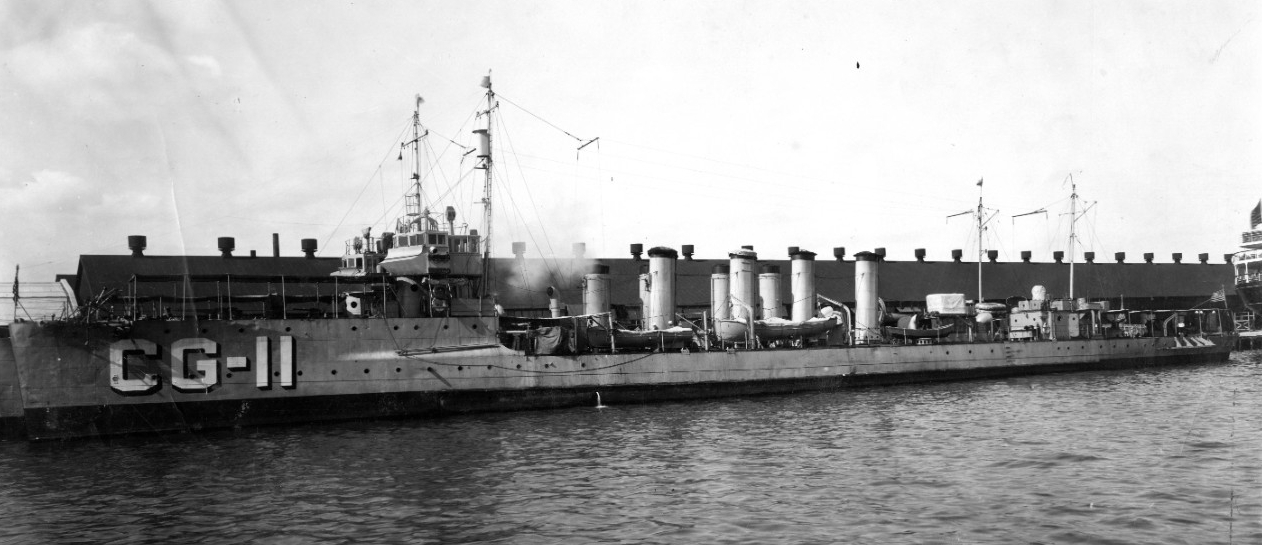

The ratification of the 18th Amendment [Prohibition] had spawned a thriving traffic in smuggling alcoholic beverages by 1924. The Coast Guard’s small fleet, charged with stopping the illegal maritime importation of liquor, proved unequal to the task. Consequently, President Calvin Coolidge proposed to increase that fleet with 20 of the Navy’s inactive destroyers, and Congress authorized the necessary funds on 2 April 1924. After less than five years of inactivity after an active career, Fanning was transferred to the Treasury Department for service with the Coast Guard on 7 June 1924.

Those who championed the transfer reasoned that adapting the vessels to law enforcement service would cost less than building new ships. In the end, the rehabilitation of the vessels became a saga in itself because of the exceedingly poor condition of many of the war-weary destroyers. Coast Guardsmen and navy yard workers went to work on Fanning. It took nearly a year to remove the installed anti-submarine warfare equipment and rehabilitate these vessels in order to bring them up to seaworthiness and operational capability.

As historian Malcolm F. Willoughby noted, “The winter of 1924-25 was exceptionally severe. Work on destroyers went on day after day in close to zero weather often without the vestige of heat. Some boilers and engines were in fairly good condition, while others were in a deplorable state. New, quick-firing, long-range guns were installed; torpedo tubes and Y guns for depth charges were removed to lighten weight and remove unneeded equipment.” Additionally, the destroyers were by far the largest and most sophisticated vessels ever operated by the Coast Guard; trained crewmen were nearly non-existent. As a result, Congress subsequently authorized hundreds of new enlisted billets. It was these inexperienced recruits that generally made up the destroyer crews.

Retaining her name, but re-designated CG-11, Fanning received instructions on 22 May 1925 to disregard all other orders and proceed immediately to New London, Conn., and report to the Destroyer Force for duty as her services were “urgently needed at once.” Fanning departed the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 30 May and arrived at New London, on 31 May, and reported to Cmdr. William H. Munter, Commander, Destroyer Force. She was placed in commission at New London, on 1 June 1925, Lt. Cmdr. James Pine, USCG, in command.

While Fanning could attain 25 knots, seemingly an advantage in the interdicting of rumrunners, she was easily outmaneuvered by smaller vessels. As a result, the destroyer picketed the larger supply ships ("mother ships") on Rum Row in order to prevent them from off-loading their illicit cargo onto the smaller, speedier contact boats that ran the liquor to shore.

Within a year of her commissioning, Fanning participated in the exercises for Gunnery Year 1925-1926. Competing against both destroyers and large cutters, she completed the short range battle practice (SRBP). In what was probably a greater indictment of the poor state of gunnery in the Coast Guard than a demonstration of her great skill, Fanning rated fourth among the 22 ships in the competition despite only hitting 3 times in 24 shots. In the following annual training, Gunnery Year 1926-1927, she finished 15th among 16 destroyers having made zero hits in 11 shots in the SRBP and not having fired in the long-range practice. In both years, after the annual training, she returned to New London to continue her routine patrols of her assigned sectors.

Fanning received orders on 20 June 1927 assigning her temporarily to Division Three as a replacement for Wainwright (CG-24) which was undergoing overhaul. Upon Wainwright’s return to duty, Fanning returned to Division Four. On 23 November 1927 she received orders to embark the Destroyer Force football team and convey them to the Coast Guard Depot at Curtis Bay, Md., where she was headed for minor repairs. A game between the Destroyer Force team and the Depot team had been arranged. After the completion of the welding repairs, the ship returned to New London with the gridders and subsequently resumed her regular duties there.

Detached from her homeport on 10 March 1928, Fanning left New London for her new homeport at the Charleston (S.C.) Navy Yard and duty with the Special Patrol Force. From here she was to patrol southern waters in an effort to stem the flow of illegal liquor from the Bahamas.

Fanning arrived at Charleston, S.C. on 20 April 1929 for the Gunnery Year 1928-1929 target practices. She only improved her standing marginally in the Destroyer Force, rating 17th among the 24 ships. Afterward, she returned to New London on 7 May and resumed her duty patrolling off New York and New England through the end of the year.

Fanning’s grueling anti-smuggling interdiction duties, however, eventually wore on her and over time she, along with seven of her fellow former Navy destroyers, Beale (CG-9), McCall (CG-14), Patterson (CG-16), Monaghan (CG-15), Paulding (CG-17), Roe (CG-18), and Terry (CG-19), had become unfit for service. Fanning was ordered, on 30 January 1930, to be laid up in ordinary at New London, Conn., after her return from target practice. She, however, became unavailable on 27 February after colliding with the British steamer Alpaca and suffering her stem and bow plating being badly twisted, leading to the recommendation that she be laid up at once. The Coast Guard decommissioned Fanning at New London on 1 April 1930. Ordered to be towed to Philadelphia Navy Yard on 12 August, she was turned over to the Coast Guard representative there and returned to the Navy Department on 24 November.

Fanning remained at Philadelphia in a decommissioned status until stricken from the Navy list on 28 June 1934. She was then scrapped, and her materials sold.

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Ens. John Borland | 21 June 1912 - 26 July 1912 |

| Lt. William N. Jeffers | 26 July 1912 - 2 July 1915 |

| Lt. Clarence A. Richards | 2 July 1915 - 26 May 1916 |

| Lt. (j.g.) George M. Cook | 26 May 1916 - 5 July 1916 |

| Lt. Charles M. Austin | 5 July 1916 - 16 March 1917 |

| Lt. Arthur S. Carpender | 16 March 1917 - 31 December 1917 |

| Lt. John H. Everson | 31 December 1917 - 13 June 1918 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Francis Cogswell | 13 June 1918 - 22 October 1918 |

| Lt. Cmdr. George N. Reeves | 22 October 1918 - 25 May 1919 |

| Lt. Jerome A. Lee | 25 May 1919 - 14 June 1919 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Fred K. Elder | 14 June 1919 - 26 June 1919 |

| Lt. John A. Vincent | 26 June 1919 - 24 November 1919 |

| Lt. Cmdr. James Pine, USCG | 1 June 1925 – 15 June 1926 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Louis L. Bennett, USCG | 15 June 1926 – 2 September 1927 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Roger C. Heimer, USCG | 2 September 1927 – 5 July 1928 |

| Lt. Norman H. Leslie, USCG | 5 July 1928 – 30 January 1930 |

Sidney M. Cheser, Christopher B. Havern, Sr., Teresa R. Hasson, and Robert J. Cressman; commanding officer list compiled with assistance of Thomas Biggs.

17 November 2017