The Navy Department Library

The American Naval Planning Section London

Published under the direction of The Hon. Edwin Denby, Secretary of the Navy

PDF Version [90.8MB]

NAVY DEPARTMENT

OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE

HISTORICAL SECTION

Publication Number 7

THE AMERICAN NAVAL PLANNING SECTION LONDON

Published under the direction of

The Hon. EDWIN DENBY, Secretary of the Navy

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE|

1923

ADDITIONAL COPIES

OF THIS PUBLICCATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM

THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON, D. C.

AT

80 CENTS PER COPY

___________

PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS

COPY FOR PROFIT. - PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAY 11, 1922

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

___________

| Page. | |

| Capt. N. C. Twining, United States Navy | Frontispiece. |

| Capt. F. H. Schofield, United States Navy | Facing frontispiece. |

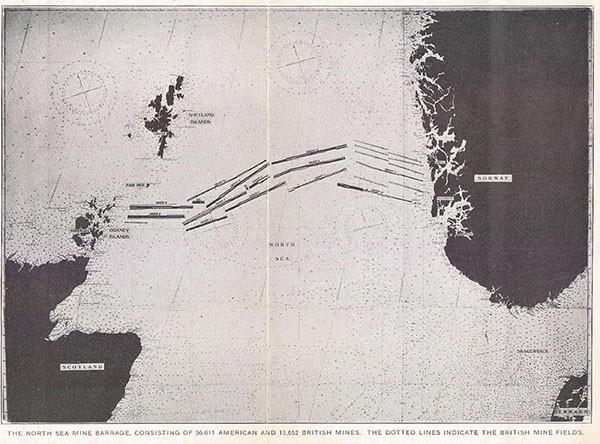

| North Sea barrage | 139 |

| Capt. Luke McNamee, United States Navy | 221 |

| Capt. Dudley W. Knox, United States Navy | 290 |

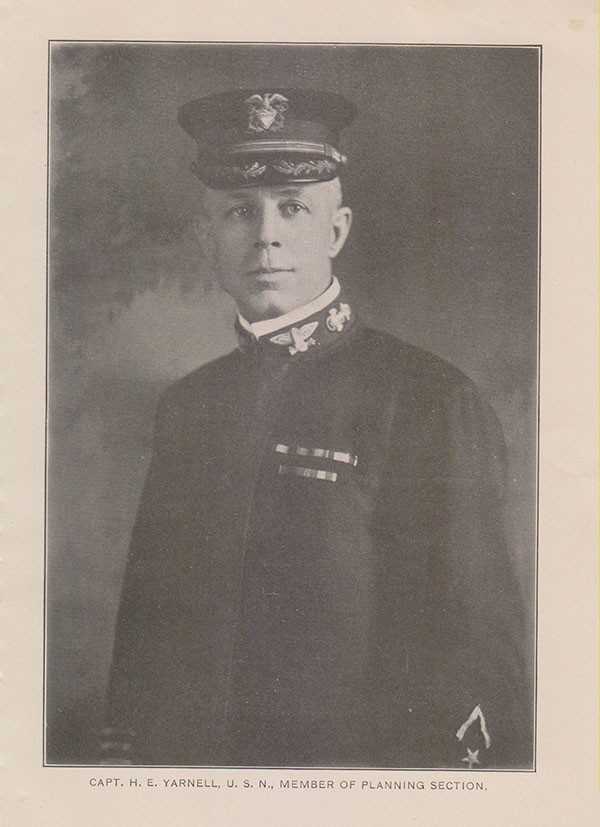

| Capt. H. E. Yarnell, United States Navy | 294 |

| United States naval headquarters, London, England | 311 |

| Col. R. H. Dunlap, United States Marine Corps | 331 |

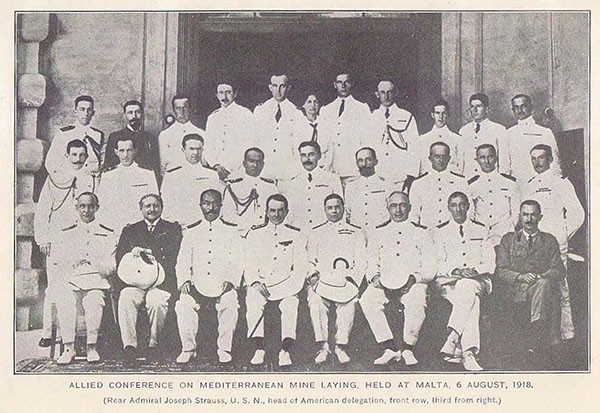

| Allied conference on Mediterranean mine laying | 384 |

| Col. Louis McCarty Little, United States Marine Corps | 412 |

| Charts 1-8 | In pocket. |

--iii--

PREFACE.

____________

This monograph is virtually a reproduction of the formal records of the American Planning Section in London during the Great War, presented in numbered memoranda from 1 to 71, inclusive. Memoranda Nos. 21 and 67 have been omitted as being inappropriate for publication at this time.

Before December, 1917, all strategic planning for the American Navy was done by a section of the Office of Naval Operations in Washington. Admiral Suns urged the need of a Planning Section at his headquarters in London, where comprehensive and timely information was more available; not only of the activities of American Forces, but of the Allied Navies and of the enemy.

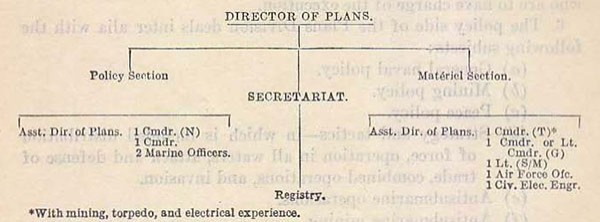

A visit to England during November, 1917, by Admiral Benson, Chief of Naval Operations, coincided with a reorganization of the British Admiralty, which included, as a result of war experience, magnification of the function of strategic planning by their War Staff. Decision was then reached to form an American Planning Section at the London headquarters of the Commander, U. S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, with the idea of cooperating more closely with the British and other Allied plan makers. Up to that time the naval strategy of the Allies often appeared to lack coordination and to be formulated primarily by men so burdened with pressing administrative details as to prevent them from giving due attention to broad plans. It was intended that the new arrangements should correct these defects.

The function of the Planning Section corresponded closely to that of similar units of organization in large businesses and in armies. Its work was removed from current administration, yet necessarily required constant information of the progress of events. It comprehended a broad survey of the course of the war as a whole, as well as a more detailed consideration of the important lesser aspects.

From an examination of these records of the American London Planning Section, together with its history contained in Memorandum No. 71, prepared soon after the conclusion of the war, it is evident that the influence of the Section upon the general naval campaign was constructive, comprehensive, and important.

D. W. Knox,

Captain (Retired), U. S. Navy,

Officer in Charge, Office of Naval Records

and Library; and Historical Section.

THE AMERICAN NAVAL PLANNING SECTION IN LONDON.

__________

Memorandum No. 1.

Submitted 31 December, 1917.

THE NORTH SEA MINE BARRAGE.

(See Map No. 1, “The North Sea,”)

_____________

We have thought that it would assist us in the study of the barrage to have in mind clearly a statement of the mission of the barrage. After study and discussion the following mission has been accepted by all concerned:

Mission.

To close the northern exit from the North Sea to submarines and raiders with the maximum completeness in the minimum time.

The way of accomplishing the mission is made up of several factors which, for the sake of clearness, may be discussed separately. First, then, let us consider the position of the barrage:

POSITION.

It is unnecessary to consider all the data which led originally to the selection of the Aberdeen-Ekersund line. It is sufficient to note that this line was at the time of its selection believed by both the British and American naval staffs to be the most acceptable position.

The second position considered in this memorandum is the one now proposed by the British Admiralty and accepted in principle by the Navy Department. There are many factors pro and con that entered into a choice as between the two positions, but of these a single factor controlled, viz, that the new position is deemed best by the grand fleet, upon which will rest the responsibility for the support and patrol of the barrage. The new position gives greater freedom of movement and greater ease of support to surface vessels, while it imposes corresponding difficulties upon the operations of enemy surface vessels. The change in position accepts the handicap of an average increase in depth of water about 15 fathoms. This handicap

--1--

might be considered serious were it not for the fact that the whole plan of the barrage is based upon the assumption that an effective mine field can be laid in 1,000 feet of water. If this assumption be true, then whether a portion of the mine field be in 40 or in 60 fathoms of water is not material, except as the change of plan introduces delay. If the assumption be not true, then the barrage is doomed to partial failure anyway.

It will be noted that the original line extended from mainland to mainland, while the new line extends from island to island and has in it passages completely navigable to submarines. This condition is, in our opinion, undesirable. We believe it wrong to accept a plan that provides in advance a way by which the plan may be defeated. This point will be discussed more fully when the character of the barrage is considered.

CHARACTER OF THE BARRAGE.

The proposed character of the barrage docs not provide for the full accomplishment of the mission. The proposed barrage will not close the northern exit from the North Sea, because—

(a) The barrage is not complete in a vertical plane in Areas B and C.

(b) The barrage is not deep enough.

(c) The Pentland Firth is open.

(d) The waters east of the Orkney Islands, for a distance of miles, are open.

(e) Patrol vessels on the surface are not sufficiently effective in barring passage to submarines, as witness the Straits of Dover.

The barrage is to be a great effort. It is our opinion that nothing short of a sound design will justify the effort.

The requirements of a sound design are the extension of the barrage complete in the vertical plane from coast to coast. If it be impracticable to carry the barrage up to the Orkneys, and to close the Pentland Firth, then the western end of the barrage should turn south to the Aberdeen Promontory.

The necessity for an opening in the surface barrage is recognized, but it is held that this opening should be in the surface barrage only, and that the deep barrage should be widened so that the difficulties of navigating the opening submerged may be practically prohibitive. Deep mines should cover for a considerable distance all approaches to the barrage opening.

The Norwegian coast presents special difficulties both in mining and patrol, but all of these difficulties will be greatly reduced by carrying the surface barrage up to the 3-mile limit. It will then be practicable to concentrate the strength of the patrol in the very near vicinity of Norwegian territorial waters.

--2--

The deep barrage in Norwegian waters should be extended so as to porcupine the coast both north and south of the surface barrage for a considerable distance. The submarine must be taught to fear all Norwegian territorial waters.

The above points concerning the character of the barrage arc points to which we attach great importance.

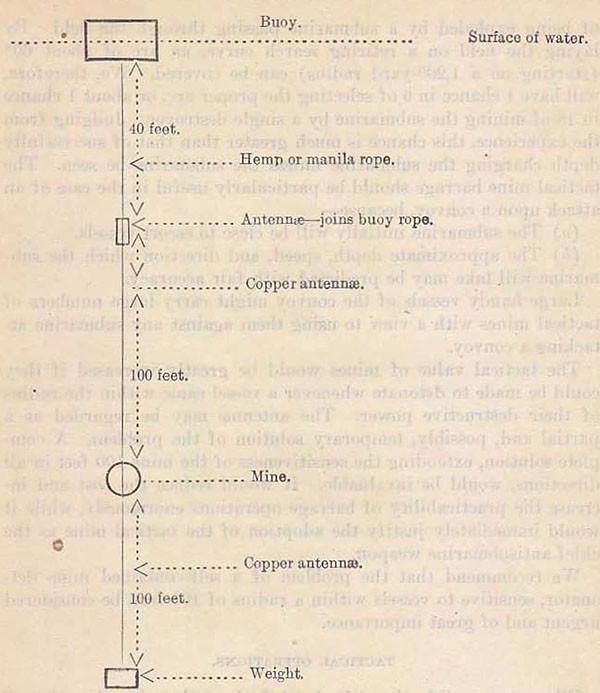

LENGTH OF ANTENNAE.

British experiments indicate that a length of antennae greater than 70 feet will not assure the destruction or disablement of an enemy submarine. This length requires three lines of mines in the vertical plane. Three lines permit the vertical barrage to be extended vertically to a depth of 235 feet. It is essential that the upper tier of mines have antennae of such length that vessels traveling on the surface may not escape, otherwise vessels might escape by the simple plan of making the passage on the surface in Area A. The necessity for short antennae is not so pronounced for the deeper mines, as the probability that submarines may make contact with the upper end of the deep antennae is much less than it is in the case of the shallow mines. The length of the antennae is related directly to the vertical width of the barrage, as follows:

(1) Three 70-foot antennae cover 235 feet.

(2) Three 100-foot antennae cover 325 feet.

(3) One 70-foot and two 100-foot antennae cover 295 feet.

Add 25 feet to each of the above depths and get the prohibited vertical zone for submarines.

We are of the opinion that the third combination should be used, as this combination provides for destruction on the surface and for reasonable certainty of destruction up to 300 feet submergence.

SEQUENCE IN LAYING.

While the sequence of laying the mines is an operating matter, it seems desirable that the situation on the Norwegian coast be cleared up by laying the fields there as early as possible.

In Area A it may be desirable to lay the southern system first and to lay all deep mines before any shallow mines are laid.

Tentative Decisions.

1. To accept the new position of the barrage as outlined by the British Admiralty.

2. To urge that the barrage be complete in the vertical plane from coast to coast, except an opening in the surface barrage at the western end and in Norwegian territorial waters.

3. To carry the barrage to a depth of 295 feet.

--3--

4. To have surface mines fitted with 70-foot antenna; and other mines with 100-foot antennae.

5. To urge that deep mine fields be laid at numerous points on the Norwegian coast.

6. To urge that all approaches to barrage openings be mined with deep mine fields for a considerable distance, so as to make the navigation of these openings by submerged vessels as hazardous as possible.

(See British comment in Memorandum No. 3.)

Comment of British Admiralty.

A. Concur.

B. It is considered this assumption is true as far as can be judged with the knowledge in our possession.

The question as to the greatest depth to which the enemy submarines may be expected to dive was discussed with our submarine experts when the depth of the barrage was decided on.

The matter has been again discussed with them since the receipt of your memorandum and they confirm their former opinion that submarines will not of their own free will dive to a depth exceeding 200 feet.

To dive under the barrage the submarines would have to dive to 240 feet in the American mine field and to 215 feet in the British mine field, measuring to the bottom of the boat, which is the German practice.

It is the considered opinion of the submarine experts that it is of more importance to effectively mine from the surface to 200 feet rather than to mine deeper with a loss of efficiency down to 200 feet.

A question which must be taken into account is whether the explosion of a charge at a depth of 200 feet has a greater radius of destruction than a similar charge at a depth of 70 feet.

Opinions differ much on this point and without direct proof, which is difficult to obtain, it is considered the effect must be assumed to be equal.

A point which requires careful consideration is whether the American mine as now being constructed will withstand the external pressure to which it would be subjected if laid at 300 feet.

The possibility of having to lay mines at 300 feet has been taken into consideration in future orders of British mines.

Taking the above points into consideration, it is requested that you will put forward any proposals you may wish to make regarding the length of the antennae.

C. The stopping power of a mine barrage such as we propose to lay should not be overrated.

--4--

It is considered that if we relied on any mine barrage across such a great width to entirely stop submarines passing out of the North Sea our hopes would be foredoomed to failure, at any rate until the barrage had become very thick.

It is the patrol craft, armed with various antisubmarine devices, on which we must rely to actually kill the submarines.

Now, the efficiency of the patrol depends on its intensity, and it is on the mine field that we rely to give us this intensity.

The introduction of the “Acoustic mine” may, and we hope will, give us an instrument which will enable us to absolutely deny large areas to submarines unless they accept the probability of almost certain destruction.

The acoustic mine is not yet a fait accompli and therefore we can not base our plans on it.

Assuming that we are correct in considering the mine field only as an accessory to the patrol, we must arrange the mine fields to that end.

When looking at the plan of the Northern Barrage it immediately occurs to one, Why not extend the surface mine field right up to the Norwegian coast?

Until we have proved the efficiency of the American mine field we must look upon it as a bluff.

It is not suggested that the American mines will not be efficient, but only whether any system of existing mines will deny an area 150 miles in width to submarines.

We notify an area 150 miles in width as dangerous and hope that the enemy submarines will be diverted into the areas on each side where our patrol craft can deal with them.

If we attempt to put the bluff too high, which it is considered would be the case if we mined the eastern area up to the surface, there would be a chance of forcing the submarines to pass through the mine field, which they might find they could do without prohibitive loss. We should then be faced with the problem of patrolling the whole area between Orkneys and Norway—a task beyond our resources.

By the end of the summer the mine fields in the notified area will, it is hoped, be so dense as to make the danger of passing through them prohibitive, in which case we could then mine the eastern area up to the surface.

It would be desirable to do this, if possible, before next winter, as our patrol craft will find it next to impossible to efficiently patrol the eastern area during the stormy winter days with long nights.

D. (a) The reason for not making it complete in Areas B and C has been explained under C.

(b) Already discussed.

--5--

(c) The navigation of the Pentland Firth by submarines when diving is not considered to be a practicable proposition. Patrol craft should prevent submarines passing through it on the surface. Also, as already explained, the patrol areas thoroughly cover the approaches to the Firth, and as it is on the patrol craft we rely to destroy the submarine the fact that it is not covered by the mine field is not considered to be of vital importance. It is clearly recognized, however, that once the barrage has one or more systems completed right across, our subsequent mine laying must be adjusted to meet any new tactics on the part of the enemy. It may for instance be necessary to continue the deep mine field down to the coast of Scotland or to mine an area to cover the western end of the Pentland Firth.

(d) The patrol craft in the Straits of Dover are not at present fitted with up-to-date hydrophone gear, nor are strong tidal waters, such as the Straits of Dover, suitable for hunting with the fish hydrophone.

The efficiency of the patrols on the Northern Barrage should not, for the above reasons, be based on results obtained at Dover up to the present time.

Submitted: Question whether the barrage should be completed on the surface up to the Norwegian coast.

The American idea of having a surface mine barrage from the Orkneys to Shetlands is presumably based on the assumption that a mine field 220 miles in length can be made so effective that it will stop submarines passing through it.

The experience of the war, it is claimed, does not bear out this assumption.

Neither do we yet know whether the American mine is efficient.

When the design of the barrage was originally considered, it was estimated that three lines of mines at each depth would be required to make it efficient.

Now, three lines of mines at each depth will not be in place until well on in the summer, even if there are no more delays than we know of at present.

Hence the mine barrage can not be considered really effective until later on in the summer, and therefore we should not attach too much importance to it.

Now, if the above assumption is correct, we should almost certainty create a situation we could not deal with if we followed the American suggestion to mine up to the surface right across, for the following reasons:

(a) The submarines would break through the mine field without prohibitive loss.

--6--

(b) We should then be forced to patrol the whole area between Orkneys and Norway with fish hydrophone vessels. We have not sufficient craft to do this.

In the British plan the patrol vessels, with up-to-date hunting gear, are looked upon as the primary means of stopping the submarines, and the mine fields are only laid with two objects:

(a) By means of the notified area to bluff the submarines into using channels which are sufficiently narrow to allow of them being efficiently patrolled.

(b) The deep mine fields to help the patrol craft to kill the submarine.

It is submitted that, re Admiral Sims’s letter A:

(а) It is first necessary to see whether the submarines avoid the notified area. If they do not, it will be necessary to go on strengthening the notified area until they do avoid it.

(b) Before committing ourselves to mining the whole area up to the surface it is necessary to find out whether the American mine is efficient.

By the end of the summer the mine barrage should be sufficiently thick to make the passage of submarines through it prohibitive, and it will probably be desirable to continue the barrage up to the surface so as to reduce our patrols on the Norwegian coast to a minimum during the winter months when the weather is bad and the nights long.

It is considered by submarine experts that it is of infinitely more importance to make the barrage efficient down to 200 feet than to have a thinner mine field down to 300 feet.

3. As the Americans are mainly responsible for the center (notified) area it is considered they should have as much latitude as possible, and it is therefore suggested that the proposal to make the length of the antennae in the lower lines 100 feet should be concurred in.

This should only be done, however, if it is quite certain that the American mines can withstand the pressure at 300 feet.

4. When the main lines of the barrage have been completed the situation should be reviewed and further mine fields laid as proposed by the American officers where experience shows them to be necessary.

5. It is not considered essential to have the bottom of the barrage at the same depth right across. To extend the mine field downward in the case of the American mines only necessitates lengthening the antennae, whereas in the British mine fields it entails laying extra lines of mines.

As already stated, it is considered of much more importance to make the mine field effective down to 200 feet before extending the

--7--

mine field lower, and in the case of the British fields the deeper mines should not be laid until the present barrage is completed.

There does not appear to be any reason, however, why this should prevent the American mine field being extended downward.

Re Admiral Sims’s letter B:

1. It is considered the areas allocated to each country should remain as at present until it is seen what progress is made, viz:

British mines to be laid in Areas B and C.

American mines to be laid in Area A.

Should it be desired at a later date to mine Area B (western area) up to the surface with American mines, it could be done with the ordinary sinkers and mooring ropes, e. g., those similar to the ones in the center Area A.

To mine the eastern area up to the surface with American mines will require special long mooring ropes.

It is suggested, therefore, that the principle of the possibility of having to mine the eastern area up to the surface at a later date be accepted, and that the United States be asked on the completion of the mining of the center area with three systems to have sufficient sinkers with long mooring ropes ready to lay two lines of surface mines across that area.

Note.—The British mooring ropes provided for the eastern area are of a sufficient length to enable surface mines to be laid in that area should it be desired later.

3. Propose to inform the United States that the necessary navigational buoys and other marks are being provided by us for all mine fields.

[Extracts from Memorandum No. 71, “ History of Planning Section.”]

MEMORANDA NOS. 1 (31 DECEMBER, 1917), 3 (5 JANUARY, 1918), 17 (12 MARCH), 35 (11 JUNE), 42 (30 JULY), 43 (21 AUGUST), 51A (18 SEPTEMBER).

Subject: “Northern Mine Barrage."

From its organization the Planning Section was thoroughly convinced of the desirability of completing the barrage at an early date according to a design which would render the passage of submarines north about as hazardous as practicable.

Believing that the speedy completion of an effective barrage required agreement in advance upon a plan by the two navies which had jointly undertaken the project, frequent discussions and conferences were held with British officials. These developed important differences of opinion as to the general characteristics of the barrage, repeated efforts were made to reconcile these differences and to reduce to writing a concrete plan which would be acceptable to both navies. These efforts met with failure in so far as formal agreement upon a written plan was concerned, the British apparently desiring to reserve the privilege of altering the plan when expediency so dictated. They were probably influenced to adopt this attitude by the intentions (not then disclosed) to undertake extensive mining operations in “the Bight,” and at

--8--

Dover, which might interfere with any agreements they made with respect to the Northern Barrage. Possibly some skepticism also existed as to the ability of the Americans to execute satisfactorily their part of the project. Doubt as to the practicability of the barrage, as well as to its strategic importance, was frequently manifested by many high British officials, notably the Commander in Chief Grand Fleet, under whose general direction the laying operations and their protection were placed. This attitude was reflected in the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff, whose department in the Admiralty handled fleet affairs. It was upon the recommendation of the Commander in Chief that the position of the barrage was moved about 50 miles northward, placing the American Section in depths of water somewhat deeper than the original position. This incident alone put back American preparations about three weeks. It became known in about September, 1918, that the hostility of the Commander in Chief to the barrage was caused in large measure by the interference that the barrage would cause to the weekly Norwegian convoy, for the protection of which the Commander in Chief was held responsible.

The British Assistant Chief of Naval Staff was hostile to the barrage, apparently because of the probable influence which it would have to reduce the number of vessels available for convoys, for which duty he was primarily responsible.

For similar reasons, affecting their own job, practically every influential British official afloat and ashore was opposed to the barrage, except the British Plans Division.

This situation caused the American Planning Section constantly to urge orally expedition in the completion of the barrage, and to emphasize its great importance in the above memoranda, as well as in other papers upon more general subjects.

It is believed that the influence of this Section, exerted so constantly, considerably advanced the completion of the barrage. But for the lack of a proper agreement in the early stages of the project, and for the opposition of British officials, it is probable that the barrage might have become effective in the early summer of 1918.

--9--

DUTIES OF PLANNING SECTION.

2 January, 1918.

____________

The cablegram from Admiral Benson which expressed his desire that a Planning Section be organized in London stated as follows:

[Cablegram.]

From: Admiral Benson.

To: Navy Department.

From my observation and after careful consideration, I believe that plans satisfactory to both countries can not be developed until we virtually establish a strict Planning Section for joint operations here (in London), in order that the personnel therein may be in a position to obtain latest British and allied information and to urge as joint plans such plans as our estimates and policy may indicate. This notion appears to be all the more necessary considering the fact that any offensive operations which we may undertake must be in conjunction with British forces and must be from bases established or occupied within British territorial waters. The officers detailed for this duty should come here fully imbued with our national and naval policy and ideas. Then, with intimate knowledge which they can obtain here from data available, actual disposition of allied forces, the reason therefor, they will be in a position to urge upon British any plans that promise satisfactory results.

(Signed) Benson.

Note.—Above cablegram was dated November 19, 1917.

In conversation with the First Sea Lord on New Year’s Day, he expressed the opinion that one of the Planning Section might be attached to the staff of Rear Admiral Keys at Dover; that another might be detailed in the Material Section of the Admiralty; and that the third officer might possibly be in the Operations Section of the Admiralty. The First Sea Lord offered these suggestions as tentative only, but seemed to dwell with some insistence on the Dover detail.

The proposed arrangement is not at all in accord with the expressed ideas of Admiral Benson and would but serve to nullify our usefulness as a Planning Section.

It is therefore proposed that it be pointed out to the First Sea Lord that the duties of the Planning Section must necessarily be more general. The United States is now involved in this war to an enormous degree. The naval vessels, and the troops on this side of the

--10--

water, are no correct measure of our participation in the war. Loans to the Allies, aggregating seven billion dollars, are being made with prospect of further loans. Our entire military effort is by way of the sea. We are intensely concerned in the measures taken to drive the Germans from the sea and in the measures taken to handle shipping at sea.

It is therefore appropriate that the Planning Section of Admiral Sims’s staff shall be free to consider those questions that seem to him and to the members of the section most urgent.

It appears to us that the principle that should govern our relations with the Admiralty is: The privileges of the Admiralty with complete freedom of action so far as the Admiralty is concerned.

These privileges and this freedom of action are essential if the Planning Section is to attain its maximum usefulness to our joint cause.

In presenting to the First Sea Lord such of these ideas as may be approved, we recommend that emphasis be placed upon our keen desire to be of the maximum possible usefulness to our joint cause.

It appears to us that we can be of most use if we work as a unit— all of us—considering, as a rule, the same subject simultaneously.

We think it desirable that we keep a continuous general estimate of the naval situation.

We think that the following special subjects should be studied by us very carefully at as early a date as possible:

(1) The Northern Barrage.

(2) The English Channel.

(3) The Straits of Otranto.

(4) The tactics of contact with submarines.

(5) The convoy system.

(6) Cooperation of United States naval forces and naval forces of the Allies.

(7) A joint naval doctrine.

Other subjects will undoubtedly present themselves faster than we can consider them, but the above illustrates the lines along which we believe our greatest usefulness lies.

--11--

FURTHER CHARACTERISTICS OF NORTHERN BARRAGE.

5 January, 1918.

____________

On January 4 the Planning Section discussed with the British Admiralty Planning Section our memorandum regarding the Northern Barrage, which was submitted on January 1, 1918.

Captain Pound stated that his Planning Section did not consider that it was necessary to carry the barrage to a vertical depth of 300 feet nor to close the ends of the barrage by a surface barrage. He stated that he was preparing a typewritten exposition of his views on the subject. He stated further that he saw no reason whatever why the American part of the barrage should not be laid down in accordance with the principles set forth in our memorandum of January 1. He said also that the British Admiralty would be prepared to extend their barrage to a greater depth if found necessary and to mine the surface should that become desirable.

We are informed by Commander Murfin that our memorandum of January 1 was shown to Captain Lockhart Leith and by him accepted in toto as sound.

Pending the decision of all points regarding cooperation in the laying of the mine barrage, we think it very desirable that the following information which bears upon the manufacture of mines should be transmitted to the Navy Department without delay:

The American Planning Section, plus Commander Murfin and Lieut. Commander Schuyler, recommend the following characteristics of mine barrage in Area A:

Length of antennae for upper mines, 70 feet from mine to top of upper float.

For all other mines, 100 feet.

Three levels of mines.

Depth of upper float of upper level of mines below surface not more than 8 feet.

Depth of lower tier of mines below surface, 298 feet.

The above characteristics of American mine field have been discussed with Admiralty Planning Division and accepted.

British propose placing their deepest mines 180 feet below surface, but will be prepared to extend barrage downward if found neces-

--12--

sary. The desirability of a deeper barrage has been urgently discussed with Admiralty Planning Section. Suggest department express its opinion that British barrage be deeper and that it be a complete barrage from coast to coast, rather than a barrage including many miles of deep mine fields only.

We recommend that strong pressure be brought to bear to have the barrage include the characteristics outlined in our memorandum of January 1, 1918.

--13--

NOTES ON SUBMARINE HUNTING BY SOUND.

4 February, 1918.

Foreword.

_____________

The following notes are based upon the best experience to date. They have been prepared by the Planning Section in collaboration with Capt. R. H. Leigh, United States Navy. Sources are—

(а) A limited experience in hunting enemy submarines.

(b) Reports and suggestions from officers engaged in antisubmarine warfare.

(c) Experimental work with friendly submarines.

(d) Deductions from tactical studies on the maneuver board.

It is realized fully that the operation of hunting submarines by sound is too new to justify hard-and-fast rules of conduct, yet better results can be obtained at the start if the rules already tentatively arrived at, and based upon experience to date, are accepted and followed than if each hunting unit determines its own rules without reference to the experience of others.

As hunting units gain experience, it is proposed to have conferences from time to time at the Admiralty of officers commanding units in various areas, so that these officers, by the exchange of ideas and by discussion, may assist in the formulation and development of the tactics most suitable for the hunting of submarines by sound-detection devices. Meanwhile all officers are cordially urged to assist in this important work by submitting criticisms of methods of hunting and suggested improvements both in methods and in material. We want the service of the best brains and energy available for this important work.

Instruments.

No description of the instruments used in submarine detection by hunting units will be attempted here, as suitable descriptive pamphlets have been—or will be—issued. The instruments will simply be enumerated and a brief statement given of their capabilities.

1. The fish is for use under way with engines stopped. Can be used when anchored in a tideway except for about one hour on each side slack water. Can be towed at any reasonable speed; can hear

--14--

submarines about 4 miles when engines of towing vessel are stopped; with amplifier this range is increased. Indicates direction of sound with a probable error of 5° to 10° if sound is distant. If sound is close aboard, directional quality disappears. Requires about three minutes after engines are stopped for an observation. Is short-lived on account of multiple wire cable.

2. The K. tube is for use when drifting, coasting (head reaching slowly), with engines stopped, or when anchored in a tideway. No towing model is available as yet. Instrument must be streamed for each observation and then taken on board before getting under way again.

Can hear submarines as follows:

| Speed of submerged submarine: | Distance (yards). |

| 0.6 knot | 2,500-3,000 |

| 2 knots | 8,000-10,000 |

| 4 knots | 15,000-20,000 |

Indicates direction of sound with probable error of 5° to 10°. If sound is very close aboard, directional quality disappears.

Requires five to eight minutes from signal to stop engines until observation is obtained and instrument is on board again ready for going ahead.

Instrument is very simple, sturdy, and reliable.

Efficiency is not interfered with by water noises of the surface in rough weather.

3. The S. C. tube is for use when stopped, when drifting, or when head reaching slowly, with engines stopped. Instrument is always in place ready for use.

Can hear submarines as follows, depending on state of sea and speed of vessel heard:

| Speed of submerged submarine: | Distance (yards). |

| 0.6 knot | 500-700 |

| 2 knots | 1,200-2,500 |

| 4 knots | 2,000-4,000 |

Indicates direction of sound with probable error of less than 5° at all ranges.

Requires about two minutes from signal to stop engines to get observation and be ready to go ahead again.

Instrument is simple and sturdy—never gets out of order.

Efficiency is interfered with by water noises and by excessive motion of vessel.

Not suitable for use in rough weather.

4. The trailing wire is for towing at slow speeds to detect a submerged submarine and especially a submarine resting on the bottom. Contact of the wire with the submarine gives instant indication of the contact.

--15--

Organization.

All listening vessels should be organized into units of three vessels each, to be known hereafter as hunting units. The vessels of each unit will habitually operate in tactical support of each other They should be sufficiently well armed—

(a) To protect themselves against the gun attack of a submarine.

(b) To attack successfully a submerged submarine when it has been located.

(c) To prevent a submerged submarine from coming to the surface and escaping by superior speed.

Note.—Hunting units operating in areas exposed to the raids of enemy surface vessels may require supporting vessels.

It is desirable that one vessel of each hunting unit be powerful enough and fast enough to cope with an enemy submarine on the surface. Whenever the hunting unit is of a class of vessels that can not meet the requirements (a), (b), and (c) above, then a special vessel, P-boat or destroyer, should be added to the unit as a support. When the listening devices are developed so that they can be used efficiently on P-boats and destroyers, these vessels, when assigned to hunting units, should replace one of the other listening vessels, so that the units shall consist of three instead of four vessels.

It is essential that the organization of units shall be permanent, so that the same vessels shall always work together. This will permit the development of real team work in tactics and in signals. The utmost skill in operation can be obtained only by continuity of association of ships and personnel.

In the matter of recognition of services rendered, it should be a principle that all vessels of a unit that actually participate in an operation shall share equally in the honor of success.

Tactics of Submarine if Pursued.

The principal cases of submarine pursuit will be—

(1) Daylight—on soundings.

(2) Daylight—off soundings.

(3) Night—on soundings.

(4) Night—off soundings.

During daylight in crowded waters the submarine operates, as a rule, submerged. If pursued on soundings during daylight while submerged, the submarine may—

(a) Attempt to escape by proceeding at maximum speed.

(b) Attempt to escape by proceeding at slow speed—say 2 to 3 knots.

--16--

(c) Attempt to escape by resting on the bottom. Submarine will probably not attempt this operation in water more than 30 or 35 fathoms deep, and will always seek bottom free from rocks and other dangers to bottoming.

(d) If near bottoming ground, may attempt to escape by proceeding slowly, stopping and balancing occasionally to listen, or stopping synchronously with the hunting unit.

(e) May anchor submerged—submarines frequently rest on the bottom; when so doing they are apt to drift slowly.

Note.—A submarine proceeding submerged can probably continue under way as follows:

| Hours. | |

| Speed 1 1/2 to 2 knots | 60 |

| Speed 5 knots | 12 |

| Speed 7 knots | 3 |

| Speed 8 to 9 knots | 1 1/2 |

| Speed 10 to 11 knots | 1 |

These rough estimates are based on the capabilities of the average submarine. Later types of enemy submarines have greater submerged radius. The surface speed of enemy submarine varies in different classes from 10 to 18 knots.

At night submarines are usually to be found on the surface charging batteries, cruising to new stations, or operating. One of the first concerns of a submarine is to keep its battery fully charged. In crowded waters the submarine finds it too dangerous to charge batteries except at night.

When operating far offshore it has much more latitude, and doubtless charges its batteries while cruising on the lookout for victims. When on the surface a submarine will probably have a little of the upper deck showing. It may be stationary or under way, depending on circumstances. If under way it can submerge in from 30 to 40 seconds; if stationary time to get under way must be added.

If discovered at night on the surface the submarine may—

(a) Attempt to escape on the surface by use of superior speed.

(b) Attempt to escape by submerging. If submarine submerges, tactics of escape will be similar to daylight tactics.

The submarine’s chance of escape when off soundings are less than when on soundings because it has no refuge and must keep under way.

In every case of attempt at escape we must expect that the submarine will use every possible means to shake off pursuit. A good guide to measures to take in pursuit is to place one’s self in the position of the pursued submarine and decide upon what steps would be taken to escape under the circumstances. It is, of course, necessary to assume that the submerged submarine can hear pursuing vessels, and that it makes no noise when its engines and motors are stopped.

--17--

Tactics.

The tactics of submarine hunting by sound may be divided into three stages :

(1) Search.

(2) Pursuit.

(3) Attack.

SEARCH.

Information of the approximate position of an enemy submarine may be gained by—

(a) Report from shore listening stations.

(b) Reports from directional wireless telegraph stations.

(c) S. O. S. calls.

(d) Reports from aircraft and vessels at sea or reports from coastal stations.

When reports of the above nature are received, hunting units will be designated to search the area near the reported position of the submarine. In the absence of such reports, the hunting unit will seek enemy submarines in areas or along routes assigned.

Three methods of search will be considered:

(1) Anchored patrol.

(2) Drifting patrol.

(3) Running patrol.

The anchored patrol may be used to establish a sound barrage along a line, or around an area in which an enemy submarine has bottomed.

Advantages are:

(а) Ease and certainty of maintenance of position.

(b) Each vessel knows bearing and distance of all other vessels of units at night or in thick weather.

(c) No necessity for using lights for position signals.

(d) Possibility of a continuous watch on all short-range listening equipment and, except at turn of tide, a continuous watch on other listening equipments.

Disadvantages are:

(a) Impracticable in rough sea.

(b) Probable delay in getting under way for pursuit.

(c) At slack water there is a period of about one hour when directional quality of all long-range listening devices disappears— this because fish and K tube do not remain on a constant heading.

(d) Loses submarine if it drifts along the bottom.

When anchored patrol is decided upon—

Use a hawser instead of chain for anchor cable, as handling chain betrays you to the submarine.

Be ready to slip instantly.

--18--

Keep the support under way always.

The best formation for anchored patrol is in line normal to the probable course of enemy submarines. In the case of a bottomed submarine the best formation is a triangle inclosing probable position of enemy submarine.

The drifting patrol may be used to establish a sound barrage along a line that shifts with the current, or around an area in which an enemy submarine is believed to be drifting. It is particularly applicable off soundings in an area where a submarine has been seen to submerge and within which the submarine must surely be.

The advantages are:

(a) No necessity for using lights.

Note.—Relative bearings can be ascertained by tapping a prearranged signal at specified times on vessel’s hull inside, below water line. Loudness of sounds will indicate approximate distances. Bearings within 3° to 5° of accuracy may be obtained by this method.

(b) Possibility of a continuous watch on all listening equipment, due to fact that own noises are not present to interfere.

(c) Enemy receives no sound warning from noises of hunting group.

Disadvantages are:

(a) Hunting unit will drift out of touch with a bottomed submarine.

Note.—Remedy by day is to anchor a buoy as a guide. In planting buoy, speed up engines to drown sound of buoy, anchor, and cable; or lower anchor by hand quietly.

(b) Submarine may attack with good chance of success.

(c) Difficult to maintain position.

Note.—Effort to regain position will betray presence of units. If all vessels move simultaneously one might continue out of sound range of the submarine, to convince submarine that area was clear.

Note.—In both the drifting and anchored patrol extreme caution is necessary to avoid making noises. Do not throw things about the deck or against the hull of the ship. Do not break up coal while drifting. Do not hammer, except when necessary, for position signals.

(d) Fish hydrophones may not be used.

(e) Engines have to be kept warmed up, thus causing noise.

The best formations for drifting patrol are the same as for anchored patrol.

The running patrol is for use in searching a large area for submarines under way. It should be used in going to and from station unless proceeding to intercept a reported submarine, when the running patrol need not be taken up until within the area of possible contact with the submarine reported.

--19--

The running patrol may sometimes be used in advance of, and out of sound of, a convoy, as a measure of protection.

In the running patrol vessels proceed on course assigned, stopping engines and auxiliaries for listening observation simultaneously at predetermined intervals. The efficient working of a running patrol requires that timepieces be kept in exact step.

The running patrol is particularly applicable for day use, as vessels are made safer from attack when under way, and if various other vessels are operating in the vicinity, these latter may be avoided, so as to prevent sound interference.

Advantages are:

(a) Covers a large area.

(b) Easy to maintain position.

(c) Engines ready for emergencies at all times.

Disadvantages are:

(a) Enemy submarines have opportunity to hear hunting unit.

Formation.—The best formation for a hunting unit of three vessels to take in running patrol is line abeam. This formation should be used in proceeding to the patrol area and while on patrol.

Support.—If the support is a destroyer or similar vessel, it should zigzag within supporting distance in rear of the listening vessels at a distance sufficiently great to prevent its noises from interfering with the sound detection of submarines.

Distance.—Distance between listening vessels is dependent on efficiency of listening equipment.

If sound radius is 3 miles, vessels may be stationed 4 miles apart; they should then stop to listen every 20 minutes.

If sound radius is 2 miles, vessels may be stationed 3 miles apart; they should then stop to listen every 15 minutes.

If sound radius is 1 1/2 miles, vessels may be stationed 2 miles apart; they should then stop to listen every 10 minutes.

If sound radius is 1 mile, vessels may be stationed 1 1/2 miles apart; they should then stop to listen every 8 minutes.

PURSUIT.

The pursuit of an enemy submarine by a hunting unit requires a thorough understanding of the game by all concerned. There must be teamwork in listening, signaling, and maneuvering. Each vessel of the unit should require practically no direction from the flag boat.

Each ship commander must be kept fully informed of all matters that bear upon the success of the pursuit. The commander of each unit is responsible for the development of the “team spirit” and “teamwork” of his group. He should hold frequent conferences of the officers of the unit while in port, for an interchange of ideas, for discussing improved methods, for eliminating causes of failure,

--20--

or lack of complete success in teamwork. He should propose situations and ask officers in turn for their decisions to meet the situations proposed, correcting decisions, and explaining corrections as necessary. It is an invaluable practice for the hunting unit commander and his subordinates to work out tactical problems on a maneuver board and to discuss each successive phase of each problem until they are all thoroughly conversant with likely situations and the ways of meeting them.

Once sound contact with a submarine has been made, nothing but bad weather should be accepted as legitimate reason for losing sound contact. The detection instruments already provided and about to be provided should enable a competent personnel to run the submarine down.

When a submarine is heard, the vessel hearing submarine reports immediately—

(1) The magnetic bearing.

(2) Estimated distance.

(3) Whether submarine is on surface or submerged; and heads toward submarine. Other vessels maneuver to take position at one-half mile distance, in line abeam of vessel that made sound contact. All vessels observe the silent interval of the pursuit, if not otherwise signaled by unit leader. The silent interval of the pursuit should be sufficiently frequent to prevent any possibility of—

(1) Submarine passing beyond hearing between silent intervals.

(2) The submarine being overrun between silent intervals.

Immediately upon the reporting of an enemy submarine, all vessels

must keep a specially sharp lookout for signals from the hunting unit leader. The hunting unit leader should keep plotted the bearing of the submarine from the leader, and the approximate relative positions of the vessels of the unit. The position of the submarine may be determined more accurately if the unit leader is given simultaneous bearings of the submarine by two or more vessels and if these bearings are plotted on cross-section paper on which has previously been plotted the relative positions of all vessels of the hunting unit. The hunting unit leader should keep all vessels of hunting unit informed of estimated position of submarine.

In moderately rough weather it is advisable to keep “weather gauge” of the submarine, as water noises interfere considerably when attempting to head into the sea, but are negligible when drifting or running before the sea.

In pursuing a submarine, assume its speed is 4 knots per hour, unless listener can give a good estimate of submarine’s speed by counting the number of revolutions of its propellers.

Overrunning a submerged submarine places the hunting unit at a distinct disadvantages, as noises astern can not be heard with any-

--21--

thing like the same efficiency as noises on the beam or ahead. Neither can the bearing of the noises heard be so accurately determined.

During the pursuit in line abeam, vessels of the hunting unit should close gradually to a distance of 400 yards, providing the submarine is heard clearly.

In the pursuit if enemy submarine attempts to synchronize use of his propellers with the hunting unit, so as to avoid danger of sound detection, one vessel of the unit should stop her engines a minute ahead of the other vessels so that it may begin its observations instantly the other vessels stop.

In inclosed or crowded waters it will be difficult to pursue a submerged submarine to exhaustion. It is therefore very essential so to maneuver as to bring about the attack as soon as possible after contact.

If during the pursuit sound contact is lost, the circumstances should indicate whether the submarine is beyond range of the listening devices, balancing, or bottoming; if balancing or bottoming is suspected, a judicious use of depth charges may cause a submarine to betray its position.

ATTACK.

Preceding the attack vessels should have been so maneuvered as to close the submarine, but with the submarine still ahead should be in line abreast, distant not more than two cables apart.

The support should not close the attacking vessels in daytime until specifically so ordered, as the noise of the machinery of the support interferes too seriously with the tracking of the submarine. Time for attack should be chosen when the indications are that the submarine is on a steady course and when the submarine is as close aboard as it is practicable to get it without overrunning it. The signal for attack should immediately follow the expiration of a silent interval. Upon signal to attack all vessels should proceed at maximum speed, the center vessel toward the estimated position of the submarine, the flank vessels toward a position that will be 200 yards on either beam of the center vessel when it begins dropping depth charges. The center vessel should drop first depth charge 100 yards short of estimated position of submarine and successive depth charges as rapidly as possible, being careful not to drop any depth charge until the preceding one has exploded or until the vessel is beyond countermining distance of the preceding depth charge. The flank vessels should begin dropping depth charges immediately after the first depth charge of the center vessel has exploded, and successive depth charges according to the rule just laid down for the center vessel. All vessels during the depth-charge, attack should steer a course parallel to the course they were steering at the time the

--22--

attack was ordered, unless the submarine gives positive indication of its presence in another area.

Time for ordering the attack will depend entirely upon the judgment of the commander of the hunting unit, unless the submarine shows itself in position for attack, when the nearest vessel should attack immediately and without signal. Vessels should not expend all their depth charges in an attack that is guided by sound alone.

If during the pursuit touch is lost with the submarine, the commander of the hunting unit must determine upon his procedure, having in mind the capabilities of his various listening devices, the advantages and disadvantages of the various forms of patrol, and the probabilities as to what the submarine would do under the circumstances.

SUMMARY OF TACTICAL PROCEDURE.

PREPARING FOR SEA.

(1) See all instruments in working order.

(2) See that listeners arc trained in their duties.

(3) Unit commander assemble commanding officers and explain plans, then by question and answer and by instruction on maneuver board make certain that tactical plans are so thoroughly understood that no tactical signals will be necessary in pursuit except—

(a) Submarine heard.

(b) Bearing and distance.

(c) Stop and start.

(d) Attack.

(e) Course to be steered.

(4) Each commanding officer of ship assemble ship’s officers, petty officers, and listeners and instruct them in plans so that they will be able to work together as a team and each one will know exactly what to do under all conditions.

(5) Set all clocks by time signal.

(6) Determine and announce frequency and length of silent interval when on running patrol.

(7) Determine and announce frequency and length of silent interval in pursuit.

PROCEEDING TO STATION.

(1) As soon as clear of harbor, form line abeam. Unit leader in center; distance between vessels as predetermined, support zigzagging a predetermined distance astern.

(2) Proceed to station carrying on running patrol unless special circumstances make it necessary to arrive on station as soon as possible.

--23--

ON RUNNING PATROL.

(1) Begin first silent interval on signal.

(2) Start and stop thereafter by clock time.

(3) Use only those instruments ordered.

(4) First vessel hearing submarine heads for it at once. Other vessels conform to the change of course, directing their movements to get in line abeam on new course at pursuit distance.

(5) All vessels at once take up frequency and length of silent interval previously described.

IN PURSUIT.

(1) Center vessel keeps submarine ahead. Right-flanked vessel keeps submarine on port bow. Left-flank vessel keeps submarine on starboard bow.

(2) Regulate speed so as not to overrun submarine previous to decision to attack.

(3) Flank vessels of pursuit line close gradually to 400 yards distance from center vessel.

(4) All vessels signal bearing and estimated distance of submarine at end of each silent interval.

(5) All vessels change course to conform to movements of submarine and requirements of subparagraphs (1) and (3) above, without signal. Guide on flag boat of pursuit line.

(6) All vessels keep sharpest possible lookout for submarine. If sighted, attack immediately.

THE ATTACK.

(1) Get as close to submarine as possible and locate its position as accurately as possible.

(2) Begin attack at full speed, center vessel heading for last reported position of submarine; other vessels closing to 100 yards on center vessel, maintaining formation line abeam and taking up parallel course.

(3) Center vessel drops first depth charge 100 yards short of estimated position of submarine. Drops succeeding depth charges as rapidly as possible, avoiding danger of countermining.

(4) Flank vessels drop first depth charges immediately after first depth charge of center vessel has exploded and drop successive depth charges according to rule just laid down for center vessel.

(5) All vessels conserve a part of their depth charges unless attack is based upon “close aboard” sighting of the submarine.

--24--

EMPLOYMENT OF AUXILIARY CRUISERS.

10 January, 1918.

___________

One of the most urgent problems of the hour is the immediate increase of tonnage to augment the supply of food and munitions. Actual sinkings by submarines do not give a true indication of actual losses in carrying capacity incident to submarine warfare. To the sinkings must be added:

(1) Vessels damaged by submarines.

(2) Vessels damaged in collisions incident to convoy operations and to running without lights.

(3) Losses in ton-miles per day due to convoy operations.

(4) Delays in port due to inadequate port facilities.

(5) Employment of merchant tonnage in naval operations.

All of these factors are cumulative and of such a serious nature as to demand the closest scrutiny to determine if it is not possible to reduce their unfavorable effect.

We have considered especially the employment of merchant tonnage as auxiliary cruisers. It is used for patrol and escort duties. It is in no sense at any time a reply to the submarine, but rather an additional target in each instance. The principal usefulness of merchant vessels as auxiliary cruisers is protection of convoys against raiders. There are no known raiders at sea now. The present situation requires that no move in the game be lost and that some risk be accepted if we are to continue the war. We therefore recommend the immediate acceptance as a principle of action: “The maximum possible employment of all auxiliary cruisers in the ocean transport of food and munitions for the support of the war.”

--25--

The following-named vessels of the Royal Navy appear to be employed in a manner not in harmony with the above principle:

| Name. | Gross tonnage. | Name. | Gross tonnage. |

| Teutonic | 9,984 | Arlanza | 15,044 |

| Columbella | 8,292 | Avoca | 11,073 |

| Alsatian | 18,485 | Ebro | 8,480 |

| Hildebrand | 6,991 | Almanzora | 16,034 |

| Orotava | 5,980 | Orcoma | 11,571 |

| Mantua | 10,885 | Orbita | 15,678 |

| Patia | 6,103 | Moldavia | 9,500 |

| Patuca | 6,103 | Himalaya | 6,929 |

| Virginian | 10,757 | Gloucestershire | 8,124 |

| Motagua | 5,977 | City of London | 8,917 |

| Changuinola | 5,978 | Princess | 8,684 |

| Edinburgh Castle | 13,326 | Morea | 10,890 |

| Armadale Castle | 12,973 | Knight Templar | 7,175 |

| Kildonan Castle | 9,692 | Mechanician | ---- |

| Otranto | 12,124 | Wyncote | ---- |

| Orvieto | 12,130 | Currigan Head | ---- |

| Ophir | 6,942 | Coronado | ---- |

| Calgarian | 17,515 | Bayano | ---- |

| Victorian | 10,635 | Discoverer | ---- |

| Macedonia | 10,512 | ||

| Marmora | 10,509 | 41 vessels | 1400,000 |

| Andea | 15,620 |

1 Approximate.

CLOSING THE SKAGERRACK.

11 January, 1918.

(See Map No. 2, “Entrance to the Baltic Sea.”)

____________

Admiral Oliver, D. C. N. S., at the British Admiralty, requested through Captain Fuller, R. N., of the Admiralty Plans Division, that the American Planning Section consider the problem of the Great Belt. Later the details of the problem were communicated to the Planning Section orally and were assembled into the statement of the problem which follows.

The Planning Section considers it desirable to state that their method of solving a problem is to conclude as to the way of accomplishing the mission. They accept the mission imposed by the statement of the problem and thereafter give their exclusive attention to the accomplishment of that mission. In some problems the mission imposed may be unsound, but the problem solver is nevertheless bound to determine a way of accomplishing the mission.

Some observations have been appended to the solution transmitted herewith.

PROBLEM 1.

[Proposed by British Admiralty, 5 January, 1917.]

General situation: The war continues.

The Allies have succeeded in blocking the entrances to German North Sea ports, except Helgoland and the Belgian ports, denying exit of enemy submarines and surface vessels. The High Seas Fleet was behind the Elbe barrage when that barrage was completed and is unrestricted in its operations except by the Elbe barrage and by such additional measures as may be taken. Enemy submarine warfare continues by submarines passing through the Sound and the Belts and issuing from unblocked ports.

Special situation: The Allies decide to deny passage of enemy vessels into the North Sea through the Skagerrack.

Required: Estimate of the situation and plans to carry the above operations into effect.

--27--

Estimate of the Situation.

Mission.—To deny passage of enemy vessels in the North Sea through the Skagerrack.

Enemy Forces - Strength, Disposition, Probable Intentions.

Strength.—The enemy naval forces consist of approximately the following:

| High Seas Fleet: | Flanders—Continued. | ||

| 20 dreadnoughts. | 6 T. B’s. | ||

| 5 battle cruisers. | 80 trawlers. | ||

| 11 light cruisers. | Unassigned: | ||

| 2 mine-laying cruisers. | 17 old battleships and coast defense ships. |

||

| 66 destroyers. | |||

| 100 T. B.’s (organized as mine-sweeping divisions). | 3 cruisers. | ||

| 12 light cruisers. | |||

| 45 trawlers. | 38 mining vessels. | ||

| Flanders: | 34 destroyers. | ||

| 14 destroyers. | 44 T. B’s. | ||

| 13 T. B.s. | About 200 submarines, of which 30 are based in Flanders. | ||

| 3 light cruisers. | |||

| 42 destroyers. | |||

We may assume:

(1) 40 submarines at seas from German ports.

(2) 45 U, U. B., and U. C. boats in the Mediterranean.

(3) 20 destroyers in Belgian ports.

(4) 20 U-boats based on Helgoland.

(5) 30 U. B. and U. C. boats based in Flanders.

We may assume all other enemy mobile naval forces as behind the barrages with no available exit to the North Sea except the Skagerrack.

The first move toward blocking operations will immediately force upon the enemy the consideration of the problem of keeping the Skagerrack open. If the blocking is complete as to the High Seas Fleet, and reasonably complete as to submarines, the Skagerrack problem immediately becomes one of first importance to the enemy. He now controls all approaches to the Baltic from the entrances to the Belts and Sound south. Blocking operations will compel him to advance his control as far north as possible. He can not afford to hold his barrage lines as at present, for then the High Seas Fleet could never hope to gain the open sea in condition for general action.

It is quite possible that the enemy may not plan any general engagement with the Grand Fleet and that he may desire to avoid precipitating such an engagement, but immediately that the High Seas Fleet is shut in the Baltic the great influence of the High Seas Fleet on allied operations in the North Sea disappears. The allied

--28--

fleets are then at liberty to close the Helgoland Bight and to guard the barrages of the North Sea ports. Further, the Allies may concentrate their forces to cover the single exit of the High Seas Fleet into the open sea. The enemy understanding this position quite as thoroughly as we do will be compelled to adopt simultaneously two courses of action:

(1) To clear the barrages of the North Sea ports.

(2) To secure to himself freedom of exit for all his forces through the Skagerrack.

By the terms of the problem we omit the consideration of (1) above and assume that the barrage is maintained. We have to consider (2). What does the enemy require for freedom of exit of all his forces through the Skagerrack?

As to submarines he requires that the Kattegat shall be free of mines and patrol craft and especially that Danish and Swedish territorial waters shall contain no submarine traps. He requires that submarines may gain the deep water of the Skagerrack without unusual risk.

As to the High Seas Fleet he requires for it an even greater degree of security in the Kattegat than for his submarines. How will he go about getting this security? There is but one answer to his situation, and that is to advance his barriers to the deep water of the Skagerrack. He would then be in touch with water across which no passive barrier could be erected and would secure to himself as much freedom of exit as possible without establishing a base in Norwegian waters.

Any barrier which the enemy may establish in the vicinity of the Skaw in order to be complete must extend into the waters of Denmark and Sweden. Under present conditions there is no doubt that he could bring sufficient pressure on those countries to cause them to mine their own waters in such a way as to join up with a German barrier outside of neutral waters. The northern barrier once in position, other mine fields in the Kattegat would be laid by the enemy in positions calculated to give tactical support to the necessary effort of his mobile forces in maintaining the barrier.

The Skaw is about 240 miles from Kiel and about 480 miles from Cromarty Firth. Whoever attempts to maintain a barrier at the Skaw must be ready to support it with capital ships and to give those ships the shelter of shore protection. Foreseeing such a necessity, it is probable that the enemy as soon as he becomes convinced that his North Sea ports are effectively blocked will occupy so much of Denmark as may be necessary to control absolutely the Belts and the Sound, the vicinity of his northern barrier, and an advanced anchorage for supporting vessels.

--29--

The enemy submarines at sea will necessarily be directed to ports other than North Sea ports of Germany. They may go to Helgoland, but the presumption of the problem is that they will return by way of the Skagerrack. It therefore becomes a matter of importance to arrange for them a proper reception. They will, so far as practicable, assist the enemy to hinder our operations.

The enemy is favored as late as the middle of March by the fact that ice may embarrass operations undertaken by us in narrow waters.

To summarize probable intentions of enemy, he will:

(1) Attempt to establish a mine barrier with suitable gates near the Skaw, requiring the participation of Denmark and Sweden or else violating the neutrality of their waters.

(2) He will occupy shore positions in sufficient force to control the northern approaches to the Belts and the Sound.

(3) He will probably occupy shore positions in the north of Jutland, so as to control his mine barriers and guard his supporting vessels.

(4) He will use every effort to keep the Kattegat completely within his control, occupying so much of Denmark as may be necessary and possibly forcing Sweden into the war.

OUR OWN FORCES—THEIR STRENGTH, DISPOSITION, AND COURSES OF ACTION OPEN TO US.

The strength of our naval forces need not be enumerated here. It is sufficient to state that they are so far superior to enemy naval forces that he is unlikely to accept a general engagement until he has first induced a partial separation of our forces. The distribution of forces is as indicated in official publications. The nearest base is about 480 miles from the Skaw.

The decision to deny passage of enemy vessels (including submarines) into the North Sea through the Skagerrack compels at once that the operations to accomplish this mission shall be to the southward of the Skaw. The Skagerrack does not lend itself to mining operations, to net protection, or to any form of passive defense. It is true that the control of the shore would cover a certain area of water contiguous to the shore, but our mission requires that whatever steps are taken shall be effective from shore to shore.

Experience has shown that a surface patrol is not in itself a barrier to submarines, even though the tendency of the surface patrol is toward greater efficiency due to advances made in submarine detection apparatus and the increased skill of the personnel operating this apparatus. We are therefore obliged to resort to mine barriers—and possibly net barriers—and to supplement these by antisubmarine patrol and by a powerful support by surface vessels. The first

--30--

question to decide then in our measures is the position of the mine barriers. We have two cases to consider:

(1) Mine barriers protected by military as well as naval forces.

(2) Mine barriers protected by naval forces only.

From the investigation of the enemy situation it is evident that no permanency in barrier arrangements that will be effective against submarines can be attained except by the military protection of the shore ends of the barriers. Barriers may be placed anywhere in the Kattegat. The farther south they are placed the greater opportunity there is to establish successive barriers, while still retaining maneuvering room for supporting vessels. The most southerly position that may be considered accessible is across the channels on either side of Samso Island. Assuming no resistance from shore, this is probably the easiest place to close both the Great and Little Belts, but from the assumptions already made it is evident that we can not expect to maintain the position except by the occupation of Samso Island, Tuno, Tuno Knob, and Seiro Island. These positions are more remote from land attack and therefore, with a given defending force, should last longer than others farther south, as, for instance, the Kullen Peninsula position, which can be attacked by land from Siaelland.

The Sound remains to be closed by a barrier and the ends of that barrier to be protected from shore. If the barrier be placed in the narrow part of the channel north of Helsingor, both ends may be protected from Siaelland.

As a delaying operation we may consider it possible to close the Belts and the Sound by the occupation of Samso, Tuno, Tuno Knob, and Seiro Islands, and of land positions near Helsingor. The Sound is the weak point in this barrier, since the shore ends can not be made secure except by military operations on a large scale—probably beyond the capacity of available forces and facilities. But since the Sound will not accommodate vessels of over 24-feet draft it will be of decided advantage to close the Belts there by shutting in the High Seas Fleet. The continuous enlargement of mine fields in the vicinity of the Sound will compel the enemy to expose his surface craft or to accept a barrier of extreme danger to his submarines.

The position next north of the Samso Island position is the Siaelland-Odde-Heilm Island-Hasenore line. Heilm Island and Siaelland-Odde Peninsula, if securely held, would give the necessary support to the shore ends of the barrier. The line is easier to patrol than the Samso Island position, but the shore position at the eastern end is far less secure. The barrier might be considered as auxiliary to the Samso Island barrier, but would by itself offer less resistance than the Samso Island barrier. The treatment of the Sound would remain unchanged were this position adopted.

--31--

The Stamshead-Anholt-Morup Tange line may be considered as the most available barrier position in its vicinity. The occupation of Anholt would give the line strength in the center, but the ends would soon be exposed to attack from shore unless a large shore force supported the ends or unless large ships were used to cover the ends.

It is, of course, understood that the mission of enemy shore activities is to cover their surface craft while they break down our barriers. The enemy will naturally desire to compel our ships to work under his guns whenever possible, as this is a distinct advantage for him. It is, in fact, sound strategy when the question is considered by itself to arrange so that enemy ships will be provoked into fighting shore batteries. We should avoid such provocation so far as foresight will permit. The Anholt line would require above 7,000 American mines as against 4,500 for the Samso Sound barrier. One-third this number of mines will put one system across at either place.

The Anholt position offers less navigational dangers for patrolling vessels.

Laeso Island might be used as the center of a barrier still farther north. Here deeper water would be encountered, requiring more mines per mile for an antisubmarine barrier. The number of American mines required would be about 7,500 for three systems. There would be the usual difficulties regarding the ends, which, however, would be some distance from rail communications.

The only remaining position for a barrier that need be considered is from the Skaw to the vicinity of Klofero Island. Whatever other barriers may be established farther south, this barrier seems to be an essential protection to vessels supporting the southern barriers against enemy submarines, as well as an additional obstacle to returning submarines. In case of the breakdown of other barriers and of the pushing back of our patrol forces from the Kattegat the Skaw barrier offers a most desirable line to hold.

The closure of the Kattegat would secure for us an area within which traffic might be regulated so as to permit efficient use of submarine-detection apparatus. The Skaw barrier would require the occupation by land forces of the north of the Skaw Peninsula and the occupation of an island position; possibly Klofero, on the Swedish coast. With a given force these positions could probably be held more securely than any of the necessary land positions of the barriers farther south. The number and character of troops and equipment necessary for this work is an Army question. It is sufficient to indicate here that the cooperation of the Army on a large scale will be necessary to any permanency of barrier effort in the Kattegat. Large land forces, however, will entail excessive demands on shipping which, at the present time, will be most difficult to meet. In view of the military and aerial advantages that the

--32--

enemy may possess in having Jutland contiguous to his territory, together with good rail communications on the Swedish coast, it is essential that our land positions be susceptible of being held with as small shore forces as possible, and be capable of being well supported by our fleet.

We come now to the consideration of mine barriers protected by naval forces alone—unsupported by the Army. We may assume at the outset that the positions already discussed are as suitable as any others for the barriers. We must recognize that mine barriers, as a submarine obstacle, can only be regarded as effective until such time as the enemy occupies the shores with shore forces and furnished protection, with his artillery, to close-in sweeping operations. We have, however, a decided advantage in that the Kattegat is generally shallow, rendering effective patrol much easier than in deep water. There are no harbors available for patrol craft and supporting vessels except on the Swedish coasts or in Danish waters in the vicinity of Samso Island. These would probably become untenable shortly, so that we should have to look for a base in Norwegian waters. Christiansand, together with adjacent waters, is a suitable place tactically. Its strategic position is excellent except for proximity to probable enemy air bases in Jutland, but this disadvantage is partly compensated for by the dispersion of anchorage ground. The irregular bottom and great number of rocks will render submarine navigation difficult and hazardous.

There is no Norwegian ports farther east equally suitable tactically which will meet strategic requirements. Skudesnaes Fiord is 100 miles farther from the Skaw than is Christiansand. It thus offers greater security against air attack, but corresponding disadvantages for a fleet endeavoring to support operations in the Kattegat. The waters of Skudesnaes are so deep as to render very difficult the berthing of a large fleet. Its defense against submarine attack is more difficult than that of Christiansand.

In view of the measures likely to have been taken by the enemy in anticipation of our projected effort, we must count on strong resistance to our operations and must count further on supporting the operations with the Grand Fleet.

DECISIONS.

(1) To prepare an expedition establishing a mine barrier at any one of the three southerly positions above discussed, plus the Skaw position.

(2) To provide a gate in the skaw barrier, but no gate in the southern barrier.

(3) To place the southern barrier in the most southerly of the three positions discussed, but to be prepared to accept a more

--33--

northerly position if enemy arrangements make the southern barrier an unprofitable undertaking.

(4) To establish an operating base at Christiansand.

(5) To support the whole position with the Grand Fleet.

(6) To arrange, if possible, for the cooperation of the Army.

Appendix.

In presenting the above solution to the Skagerrack problem we submit the following comments on the problem: