The Navy Department Library

Solomon Islands Campaign: X

Operations in the New Georgia Area 21 June – 5 August 1943

PDF Version [13.5MB]

Copy No. 2 COMBAT NARRATIVES

Solomon Islands Campaign: X

Operations in the New Georgia Area

21 June – 5 August 1943

“COMBAT NARRATIVES were written to fill a temporary requirement before the appearance of official and semiofficial complete histories. Due to hastily gathered and oftentimes incomplete information there are certain inaccuracies.”

CONFIDENTIAL

[DECLASSIFIED]

Office of Naval Intelligence

U. S. Navy

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D. C.

October 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U. S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

[SIGNATURE]

REAR ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence.

CONFIDENTIAL

[DECLASSIFIED]

II

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publication Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

[SIGNATURE]

ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

III

Charts and Illustrations

| Facing page | ||

| Chart: The Solomon Islands Area | VI | |

| Chart: The New Georgia Group | ||

| Illustration: Night Bombardment of Munda 11-12 july | I | |

| Chart: The Landing on Rendova | 10 | |

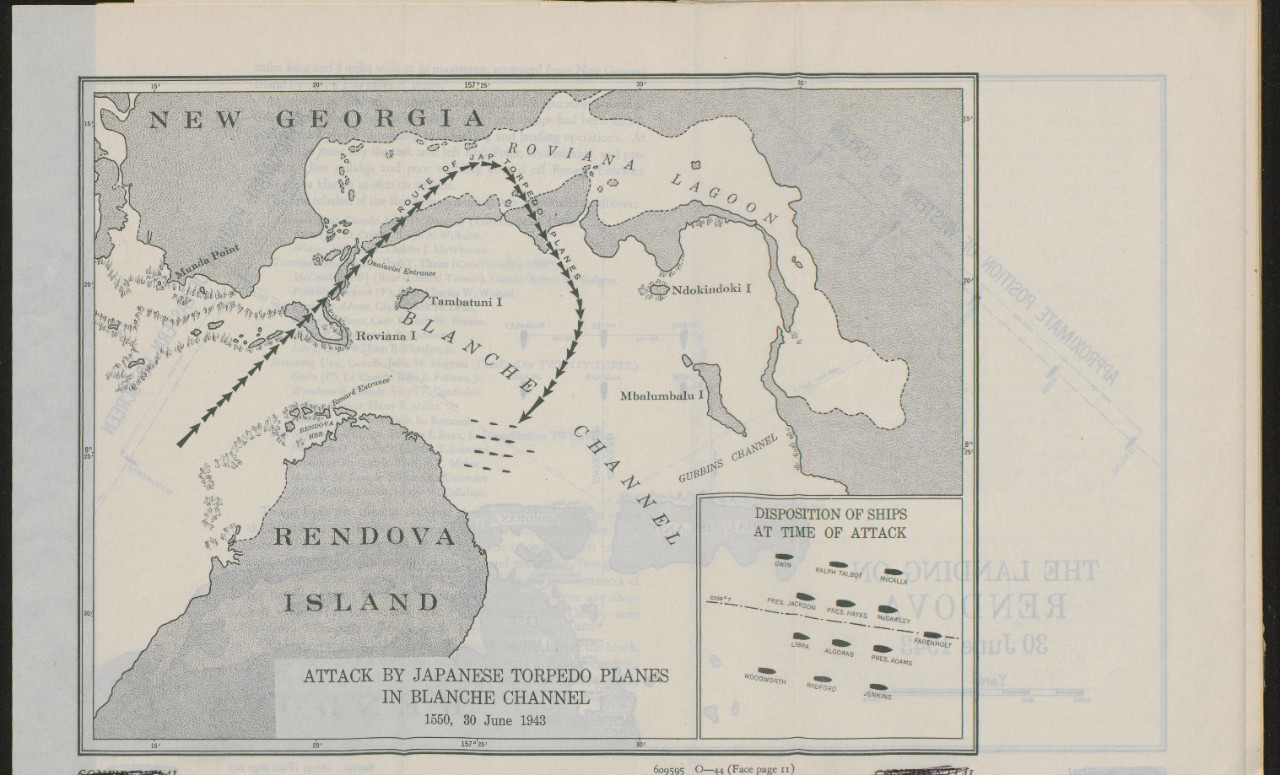

| Chart: Attack by Japanese Torpedo Planes | 11 | |

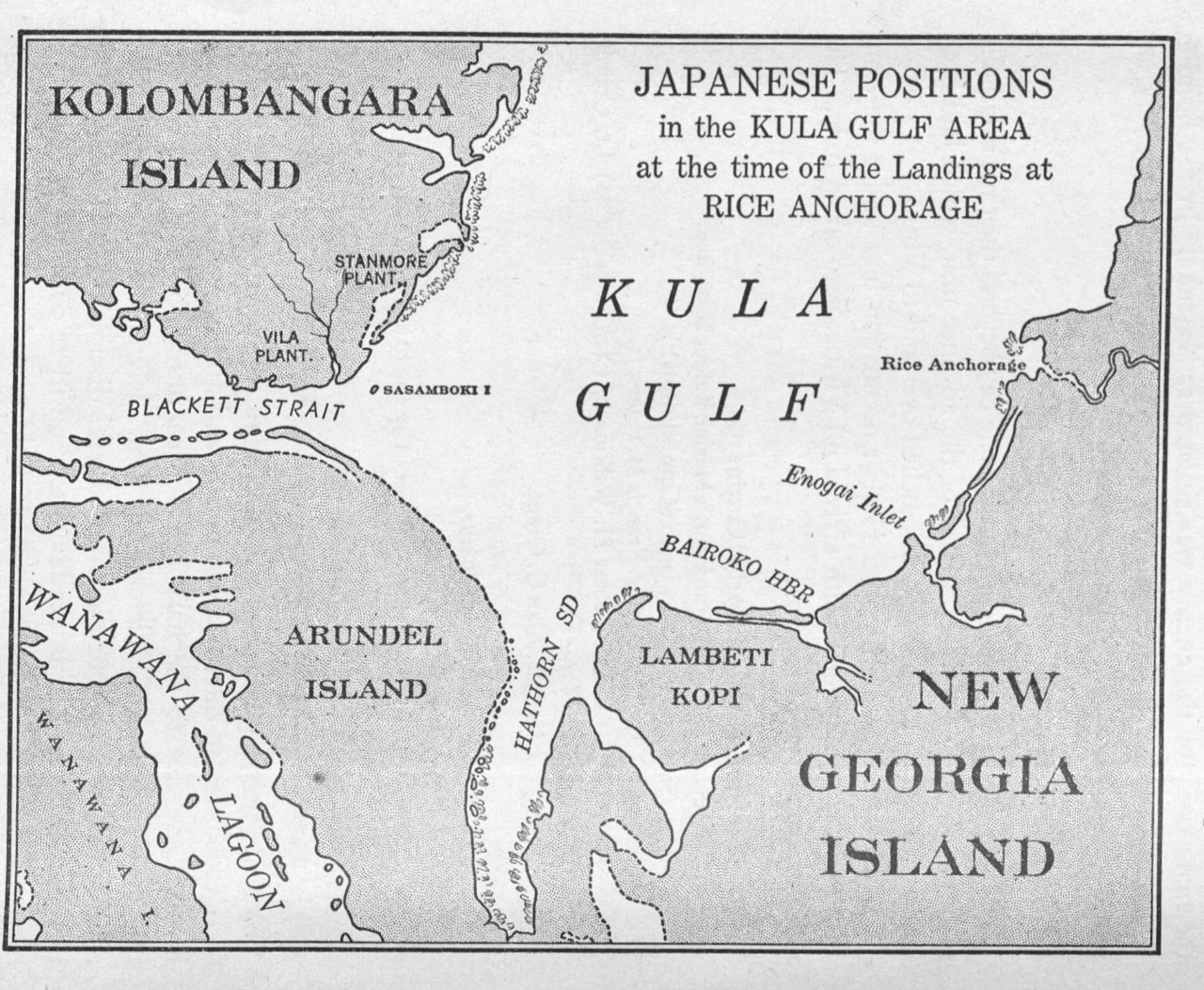

| Chart: Japanese Positions in the Kula Gulf Area | on page | 18 |

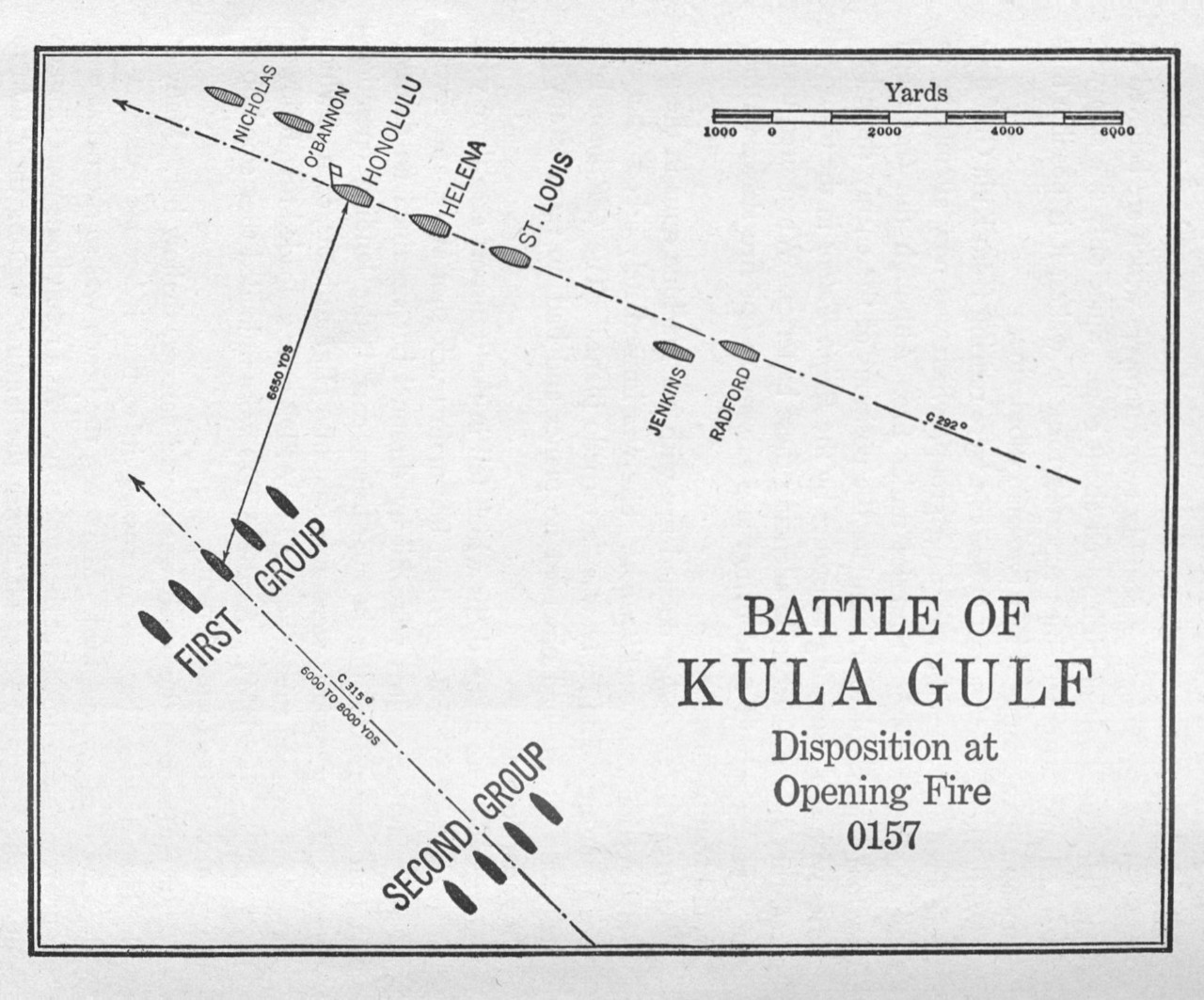

| Diagram: Battle of Kula Gulf, Disposition at Opening fire | on page | 22 |

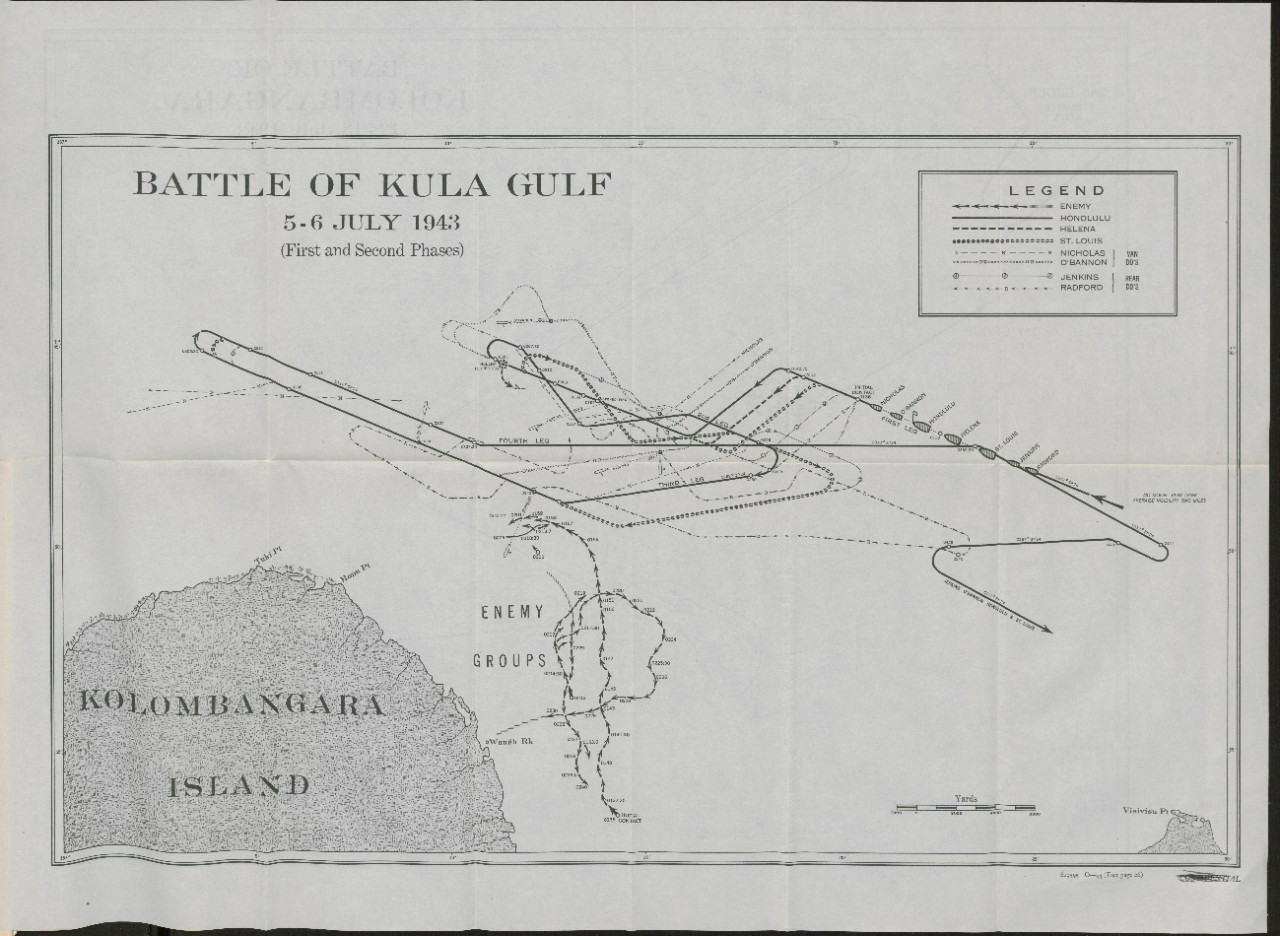

| Chart: Battle of Kula Gulf, First and Second Phases | ||

| Illustration: The Helena | 26 | |

| Chart: The Battle of Kolombangara | ||

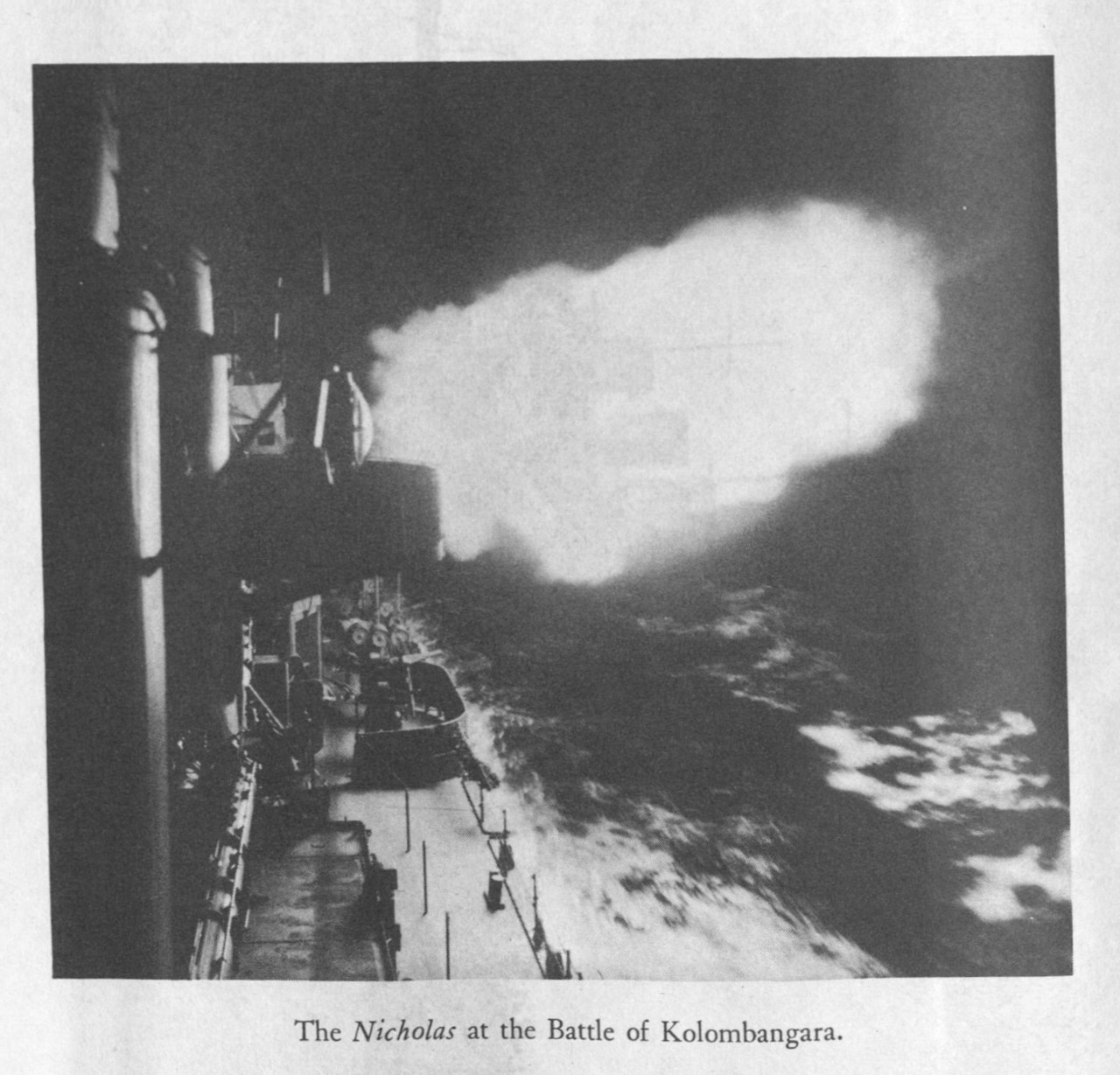

| Illustration: The Nicholas at Kolombangara | 27 | |

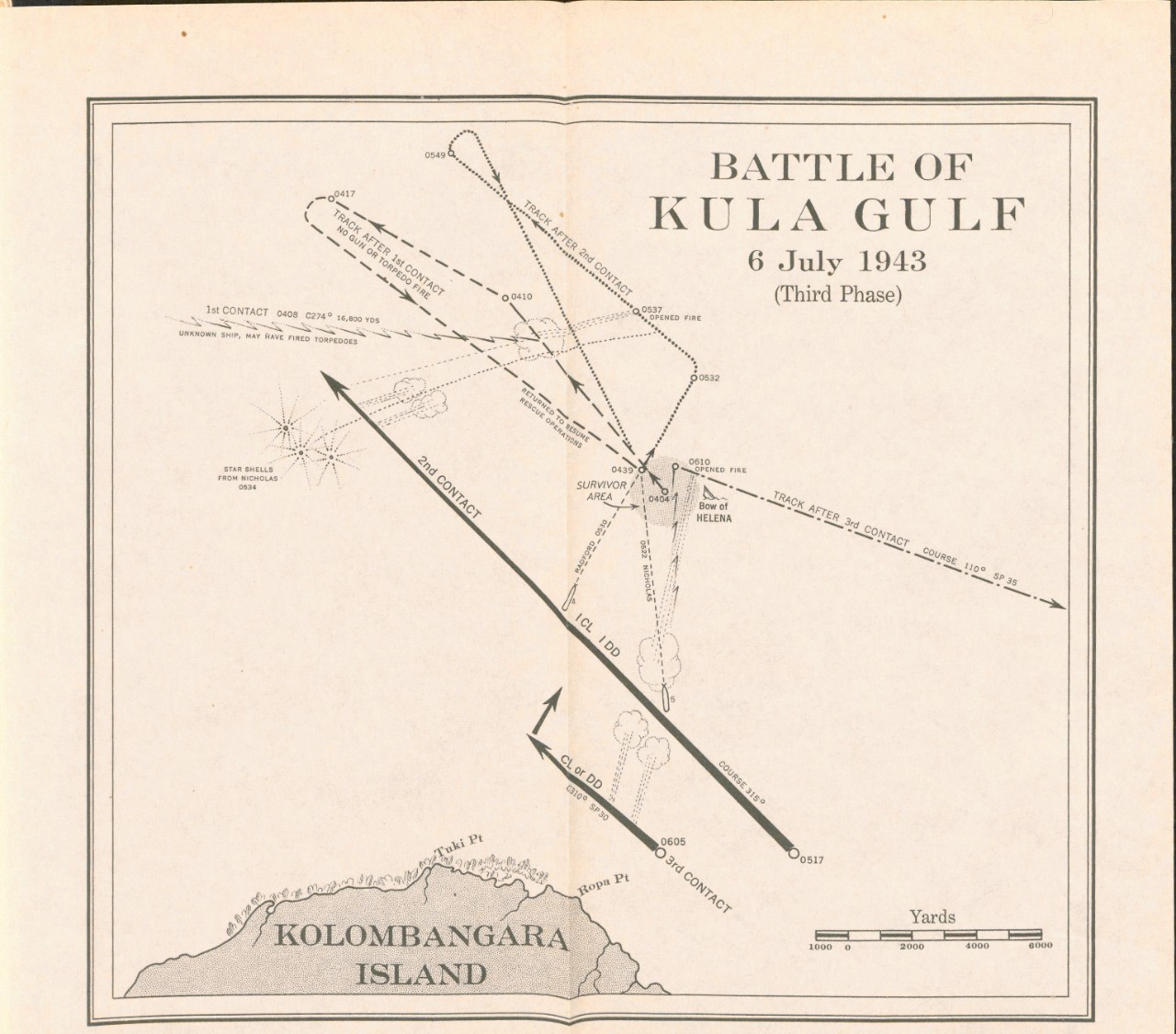

| Chart: The Battle of Kula Gulf, Third Phase | 28 | |

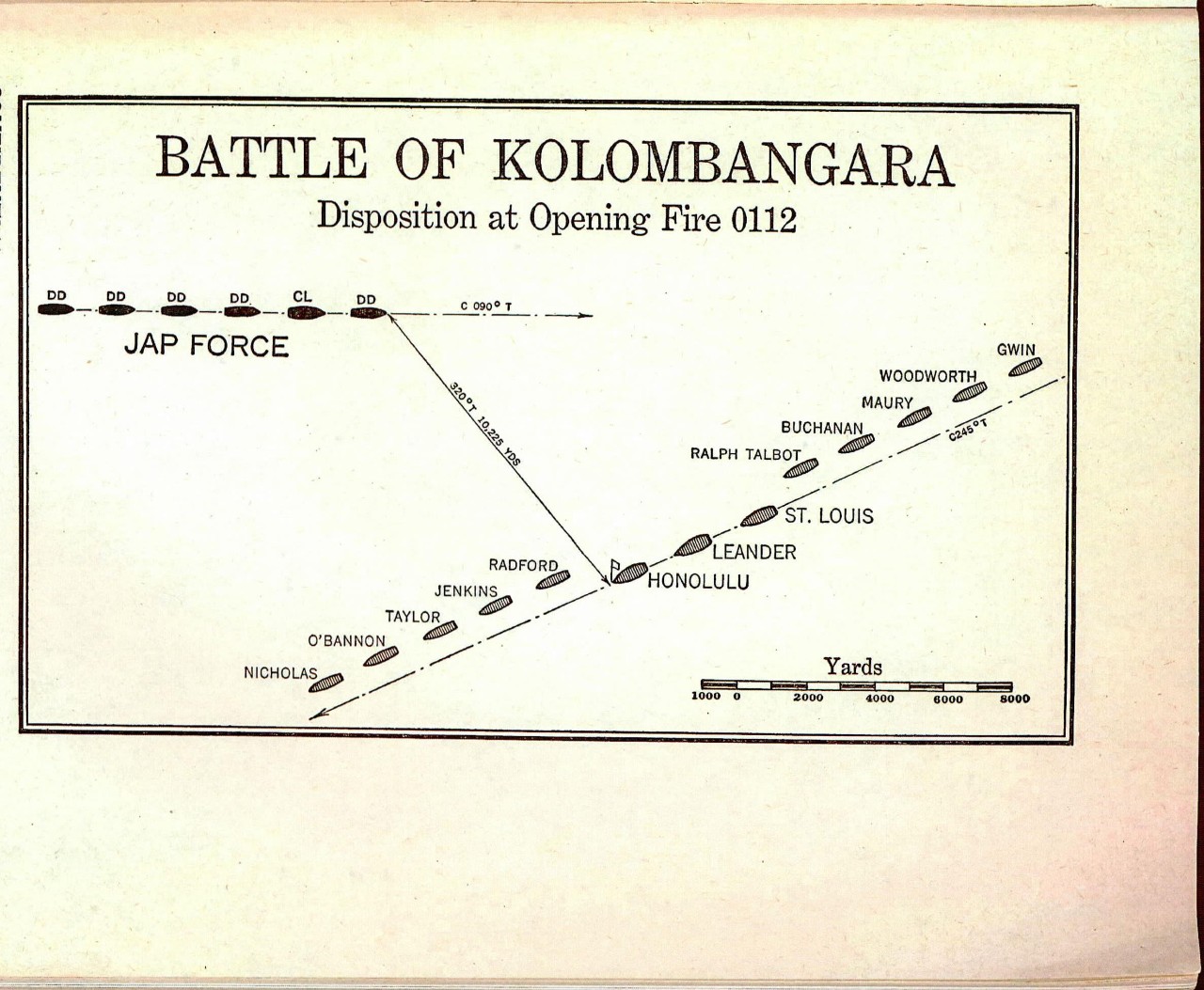

| Diagram: Battle of Kolombangara, Disposition at Opening Fire | on page | 37 |

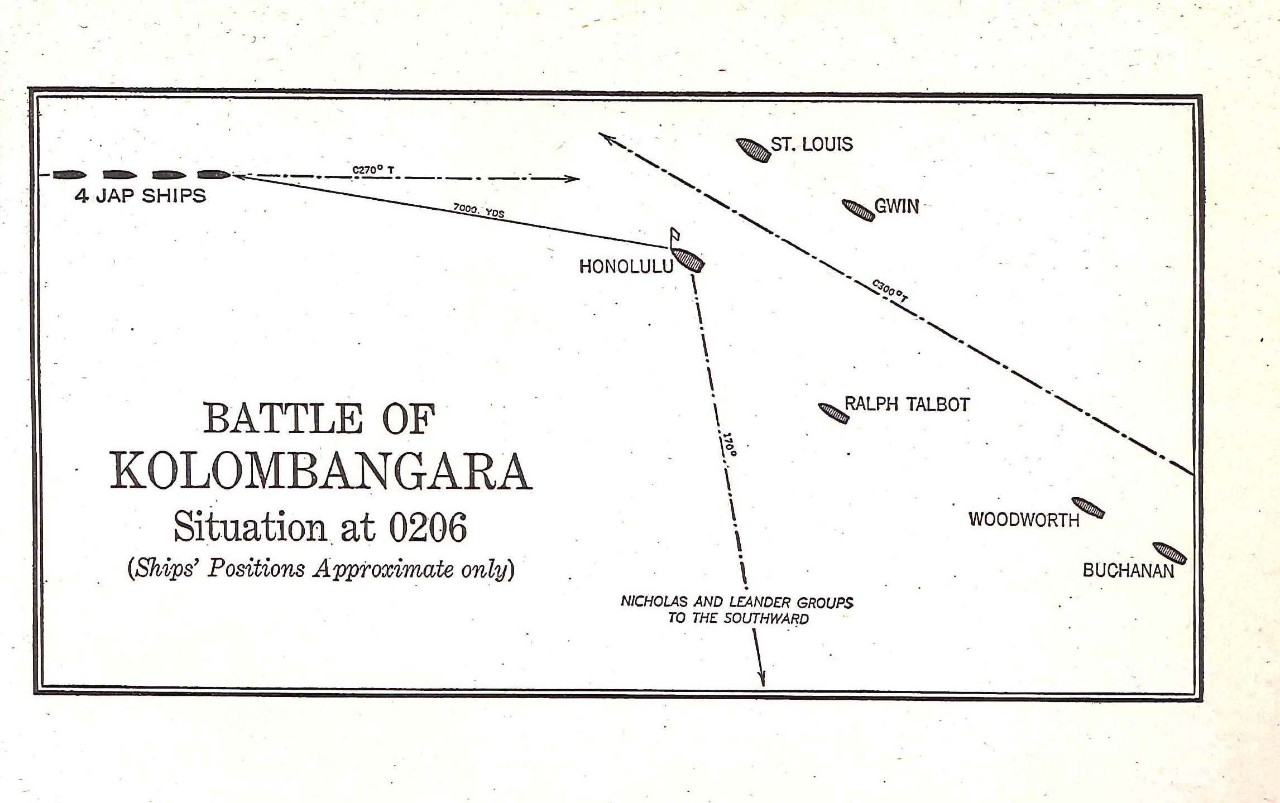

| Diagram: Battle of Kolombangara, Situation at 0206 | on page | 41 |

| Illustrations | between pages | 58-59 |

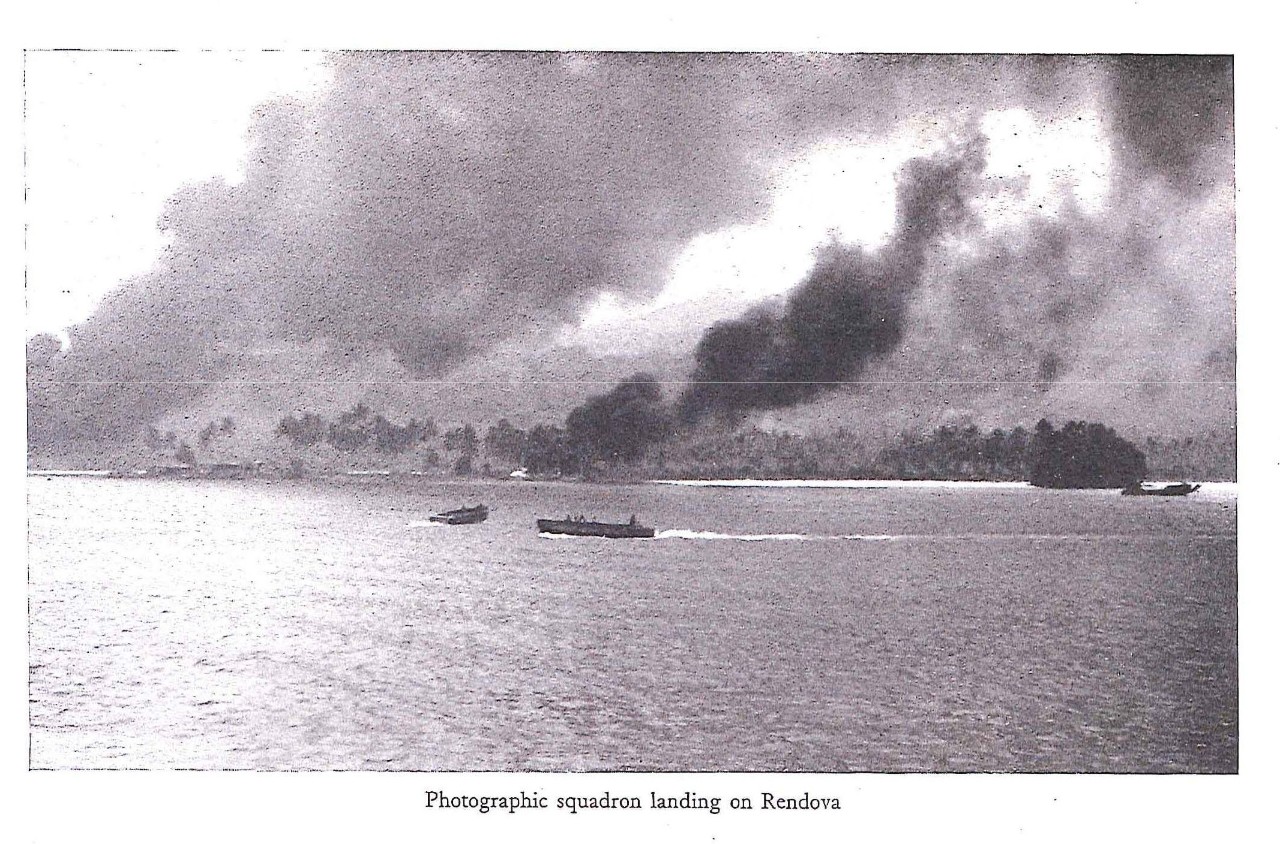

Photographic squadron landing at Rendova

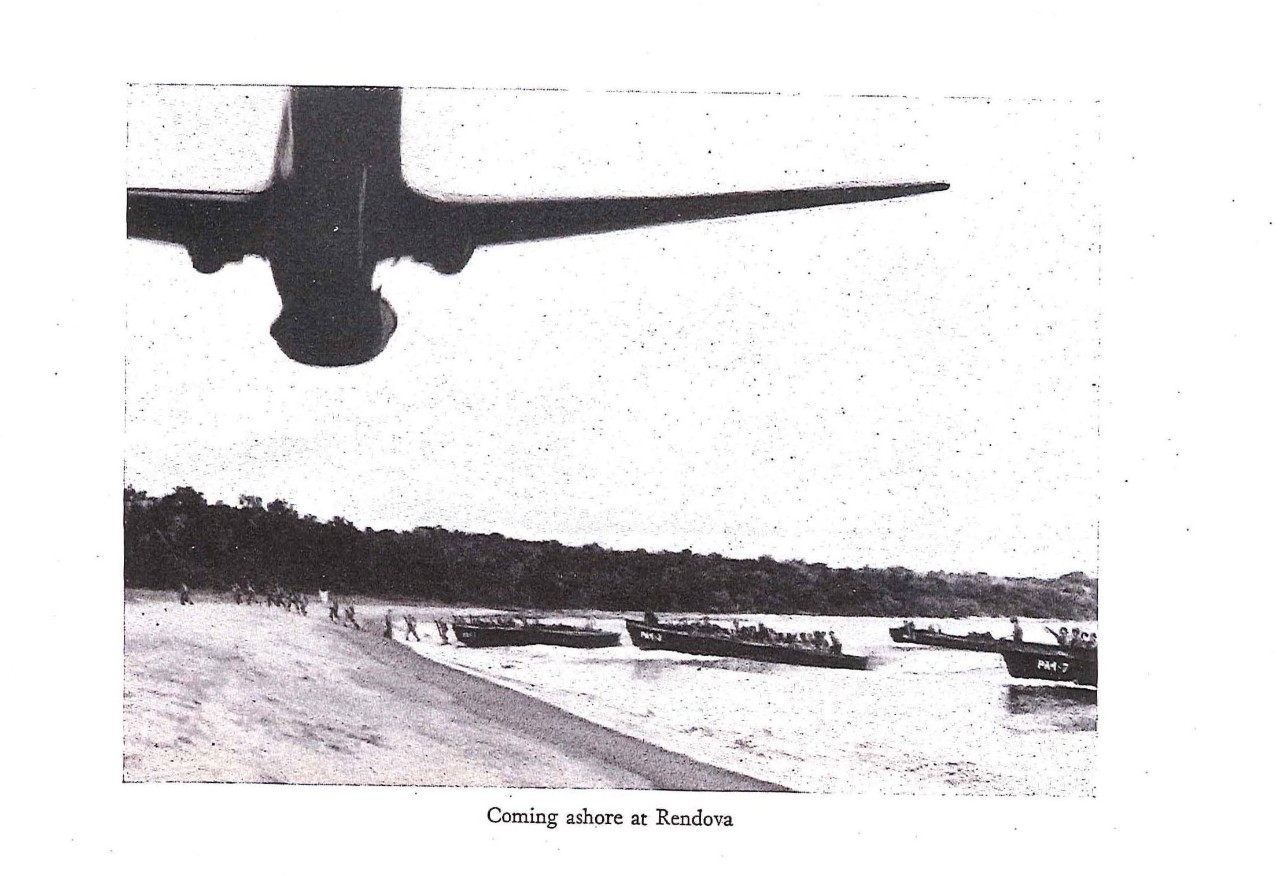

Coming ashore at Rendova

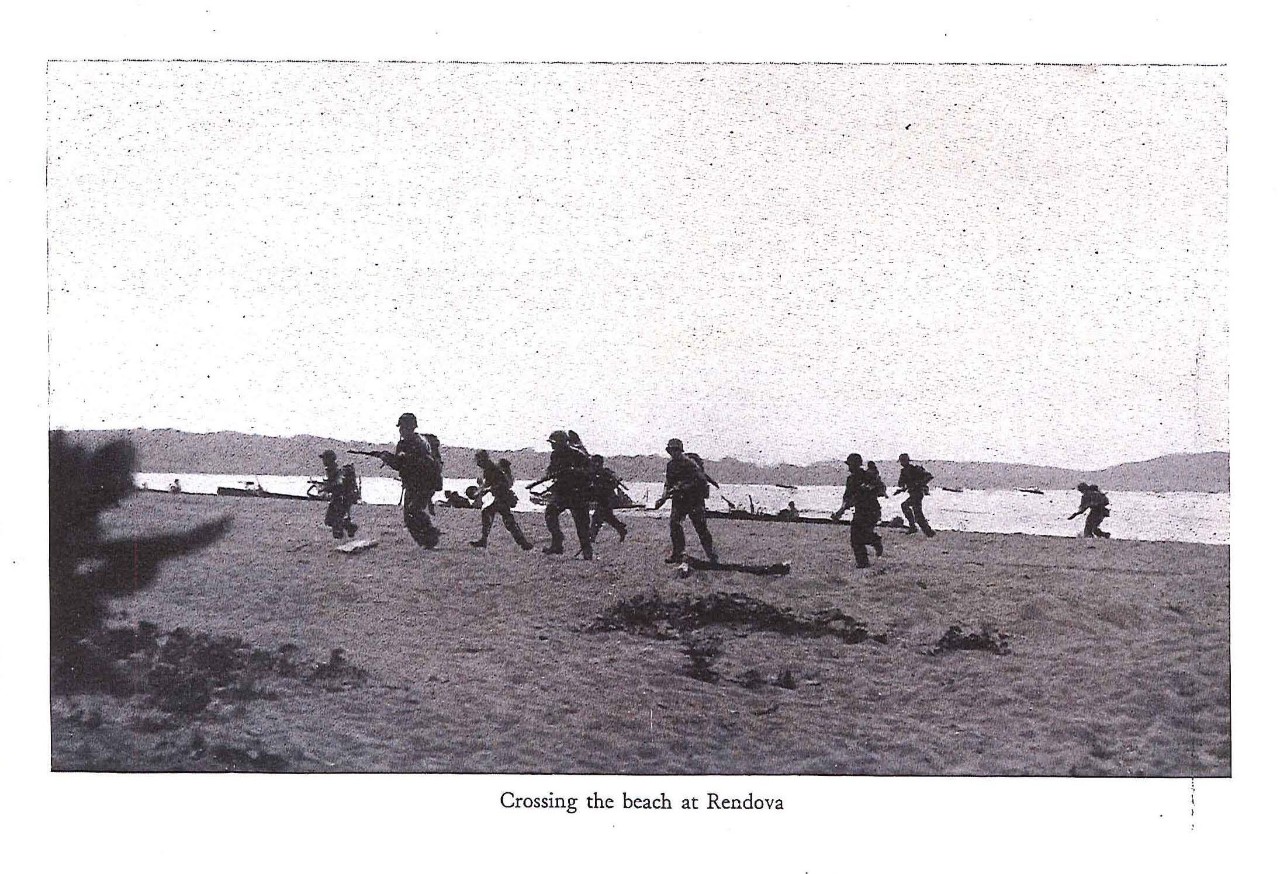

Crossing the beach at Rendova

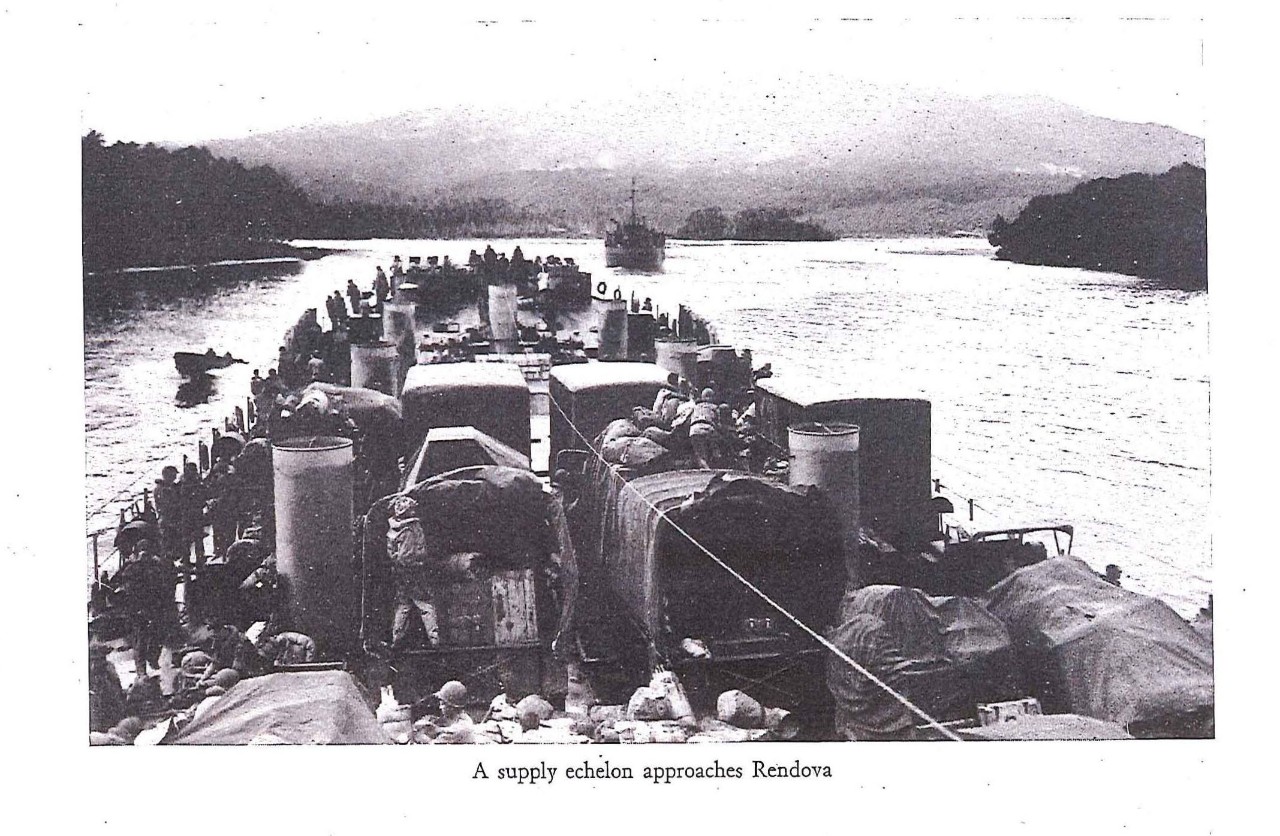

A supply echelon approaches Rendova

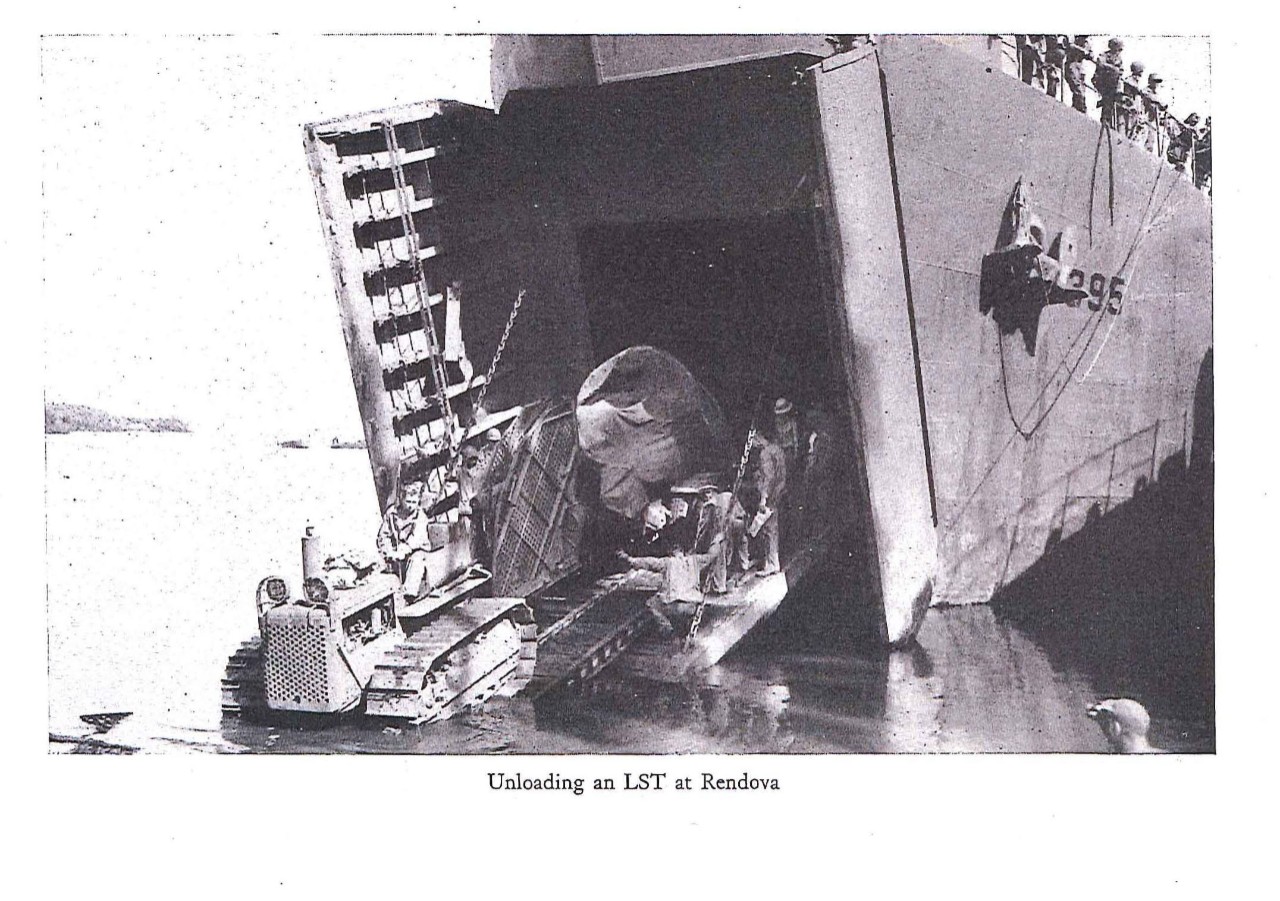

Unloading an LST at Rendova

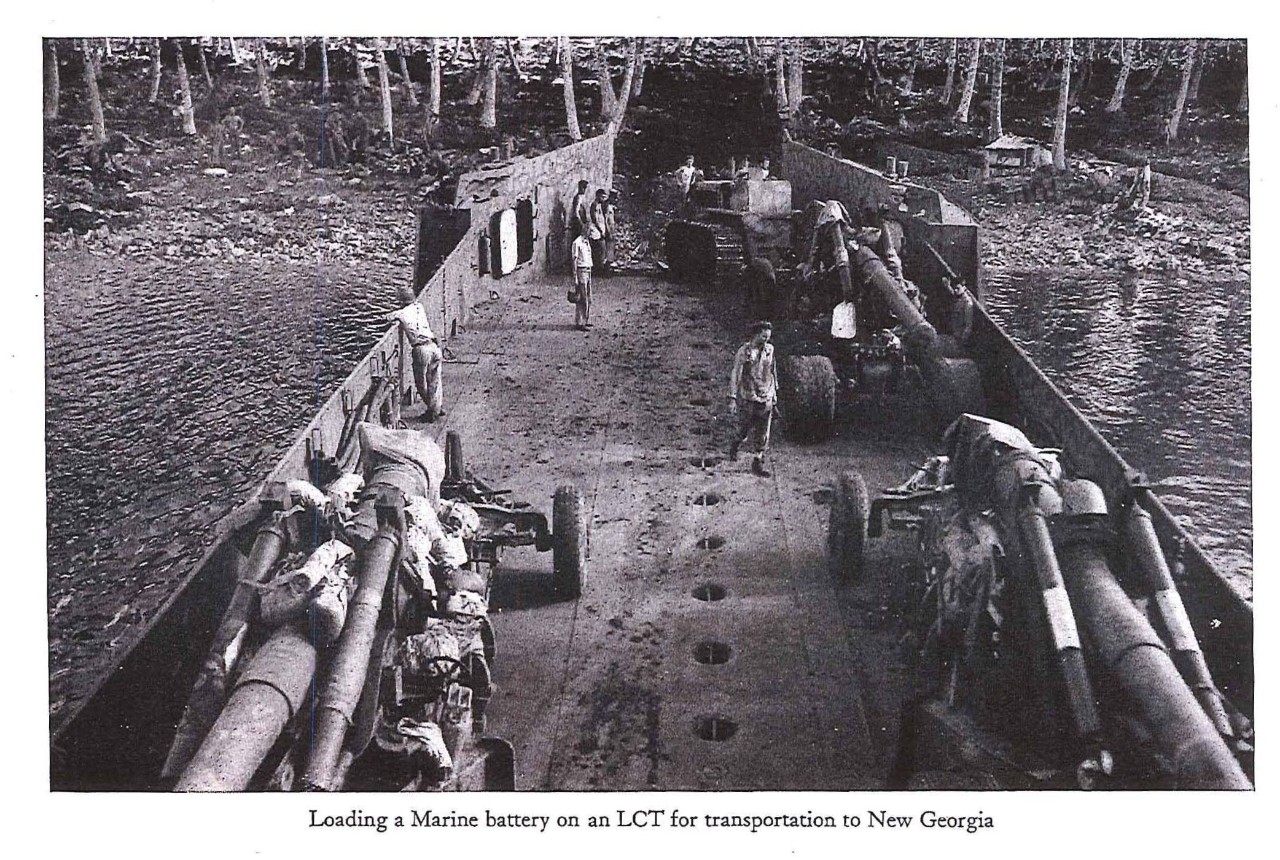

Loading a Marine batter on an LCT

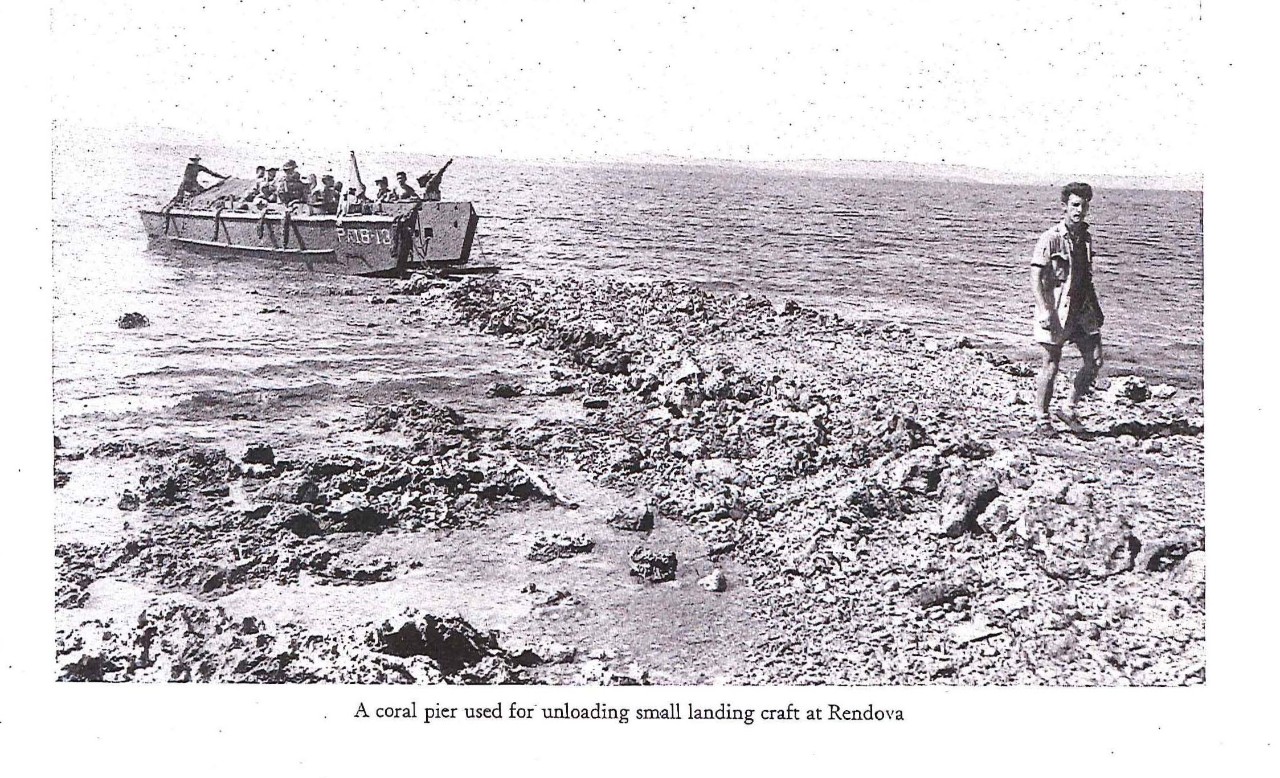

A coral pier at Rendova

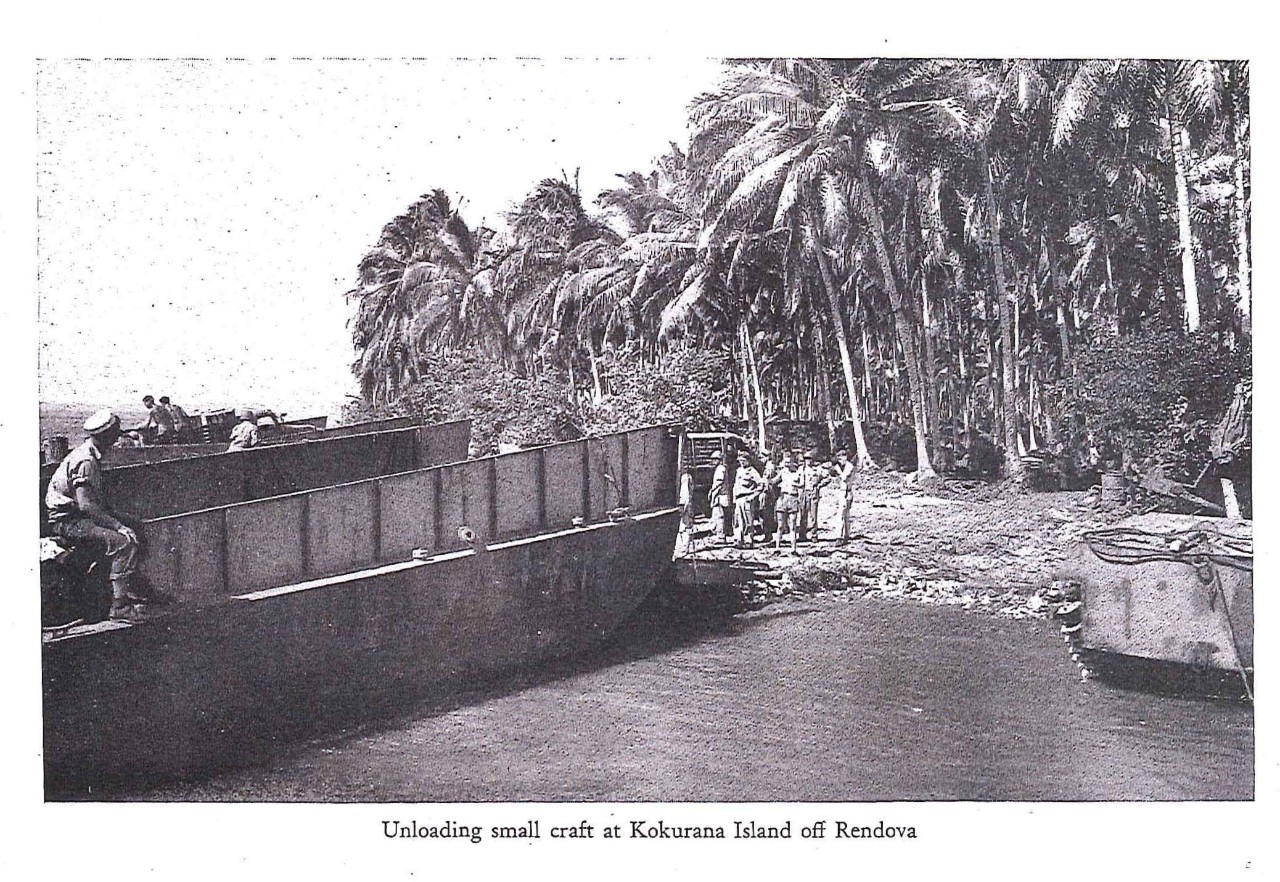

Unloading small craft at Kokurana Island

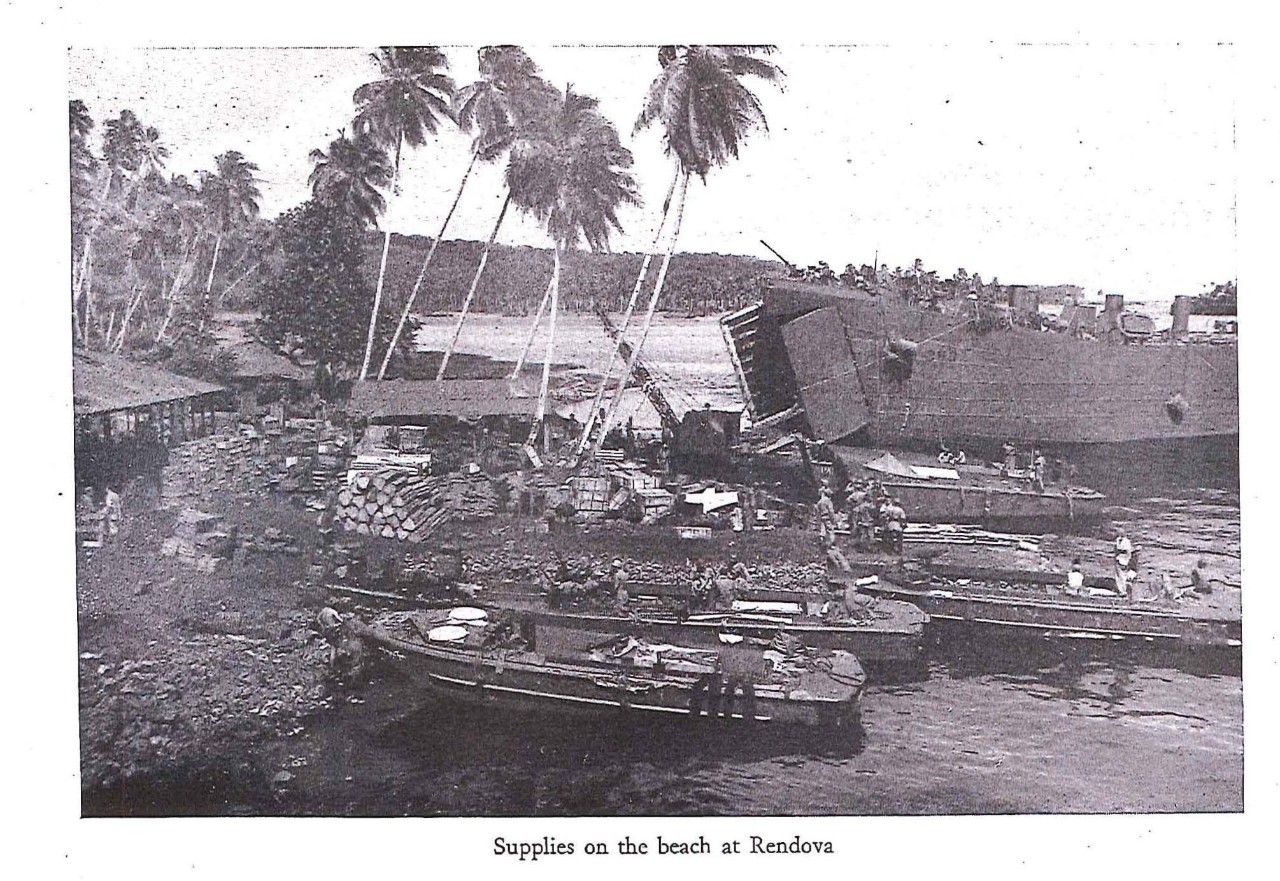

Supplies on the beach at Rendova

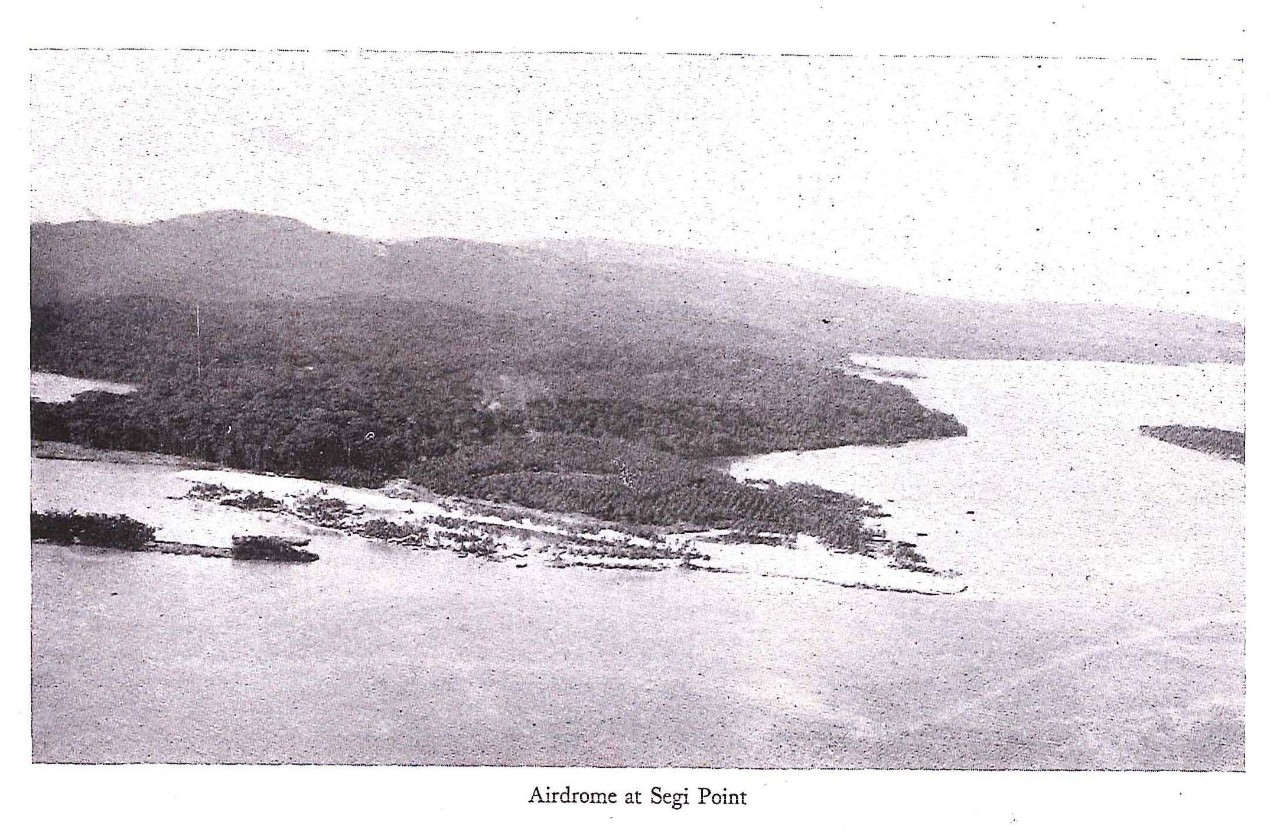

Airdome at Segi Point

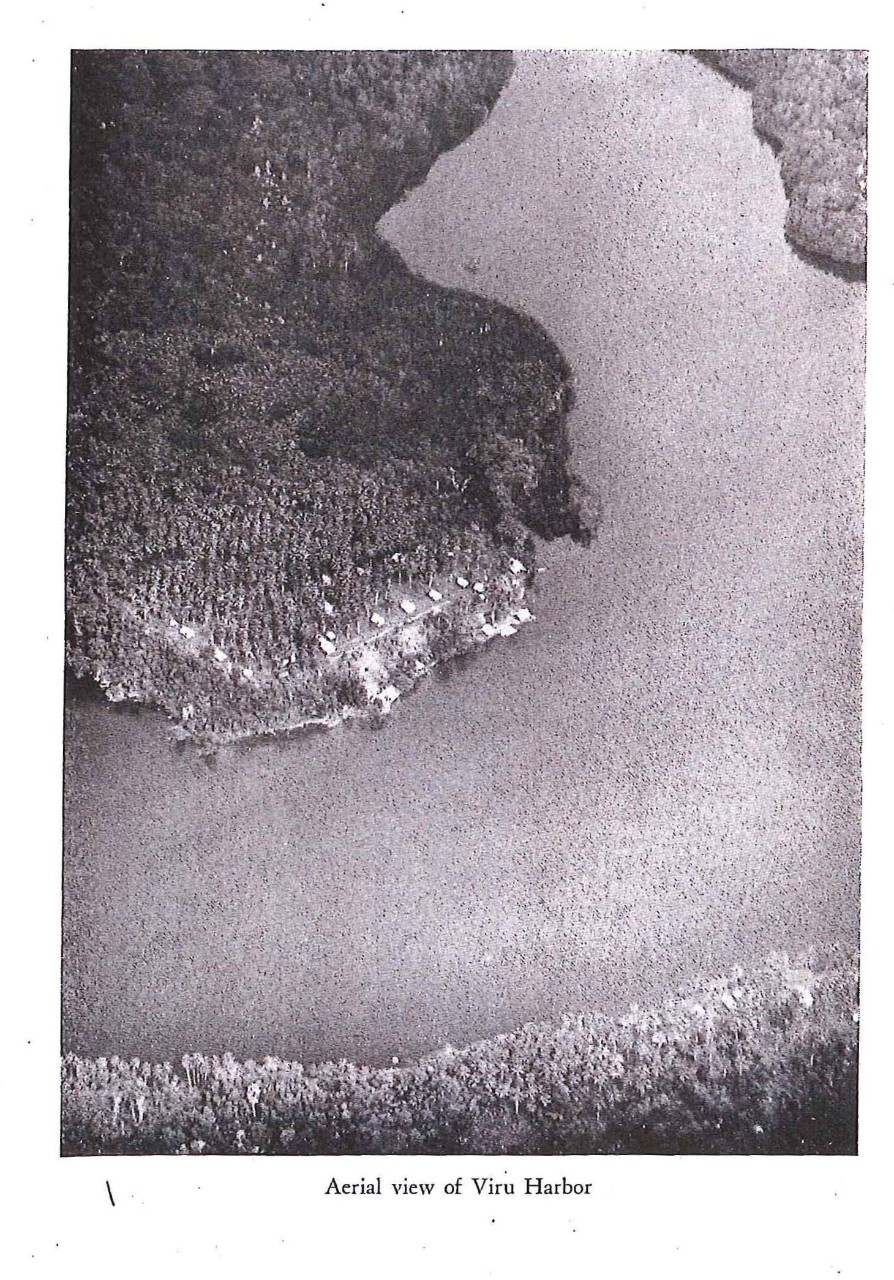

Aerial view of Viru Harbor

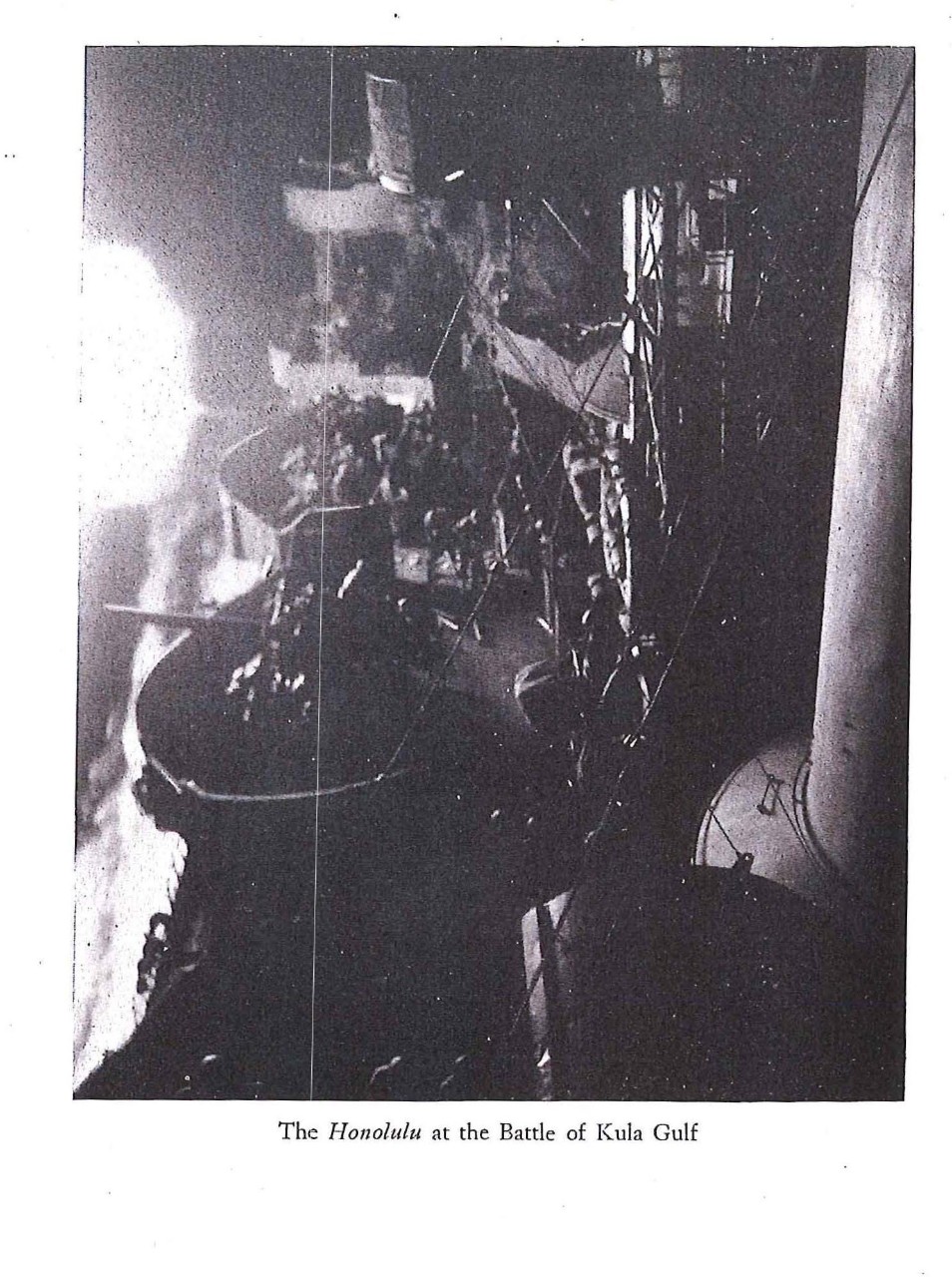

The Honolulu at the Battle of Kula Gulf

The Helena at the Battle of Kula Gulf

Japanese ships burning during the Battle of Kula Gulf

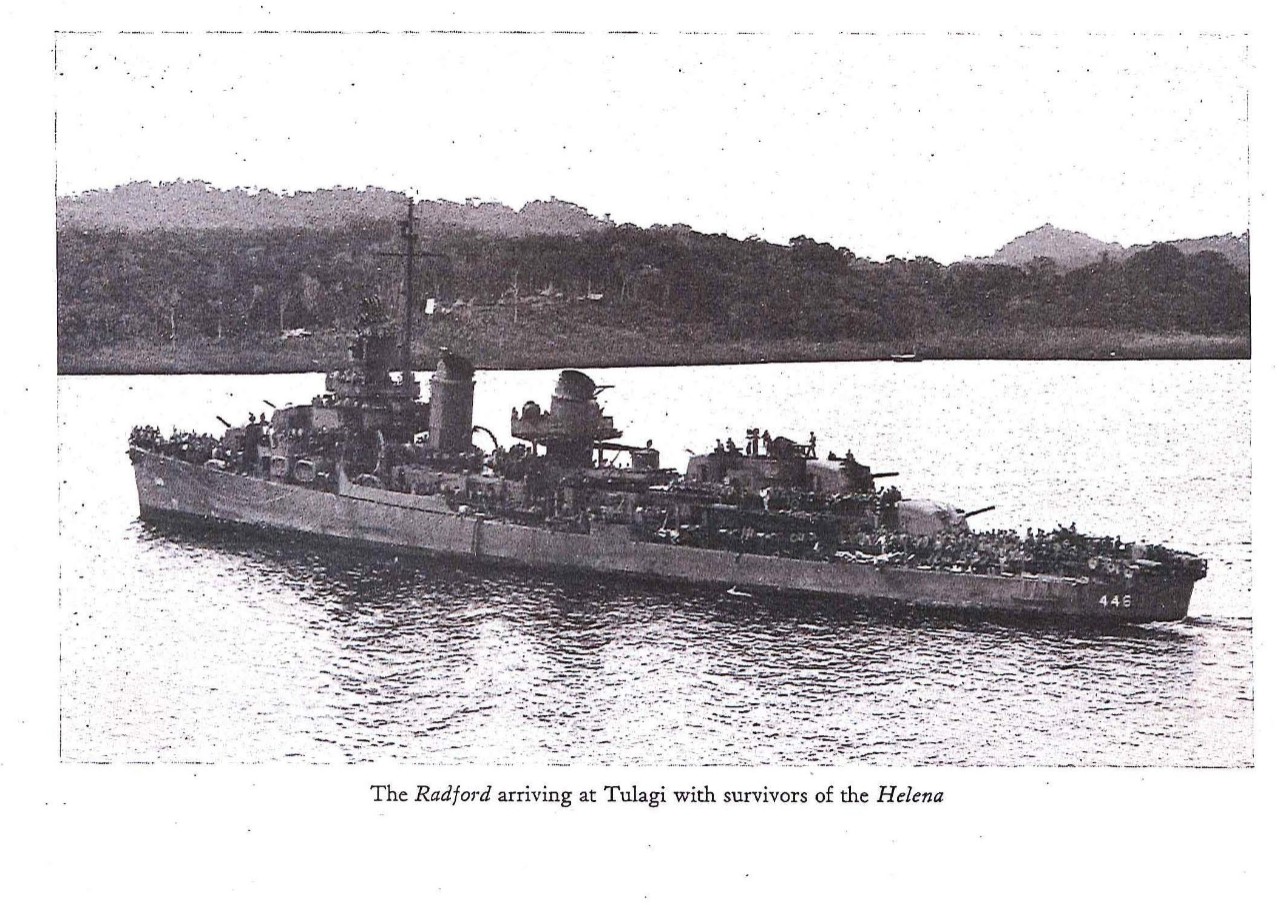

The Radford arriving at Tulagi with survivors of the Helena

The Nicholas firing during the Battle of Kolombangara

IV

Contents

| Page | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Preliminary Bombardments of Munda | 2 |

| The Occupationof the Russell Islands, 21 February 1943 | 2 |

| Logistic Preparations | 3 |

| Estimates of Enemy Strength | 4 |

| Plan of Attack | 4 |

| Task Frce Organization | 5 |

| Preliminary Movements | 6 |

| The Landing at Segi Point, 21 June 1943 | 9 |

| The Landing on Rendova, 30 June 1943 | 15 |

| Other Landing in the New Georgia Area | 15 |

| Onaiavisi, 30 June 1943 | 15 |

| Wickham Anchorage, 30 June 1943 | 16 |

| Viru, 1 July 1943 | 17 |

| Rice Anchorage, 5 July 1943 | 19 |

| Battle of Kula Gulf, Night of 5-6 July 1943 | 23 |

| The Approach | 23 |

| First Phase | 24 |

| Second Phase | 25 |

| Third Phase | 27 |

| Comments and Conclusions | 29 |

| Naval Bombardments of Munda | 31 |

| Bombardment, Night of 8-9 July 1943 | 31 |

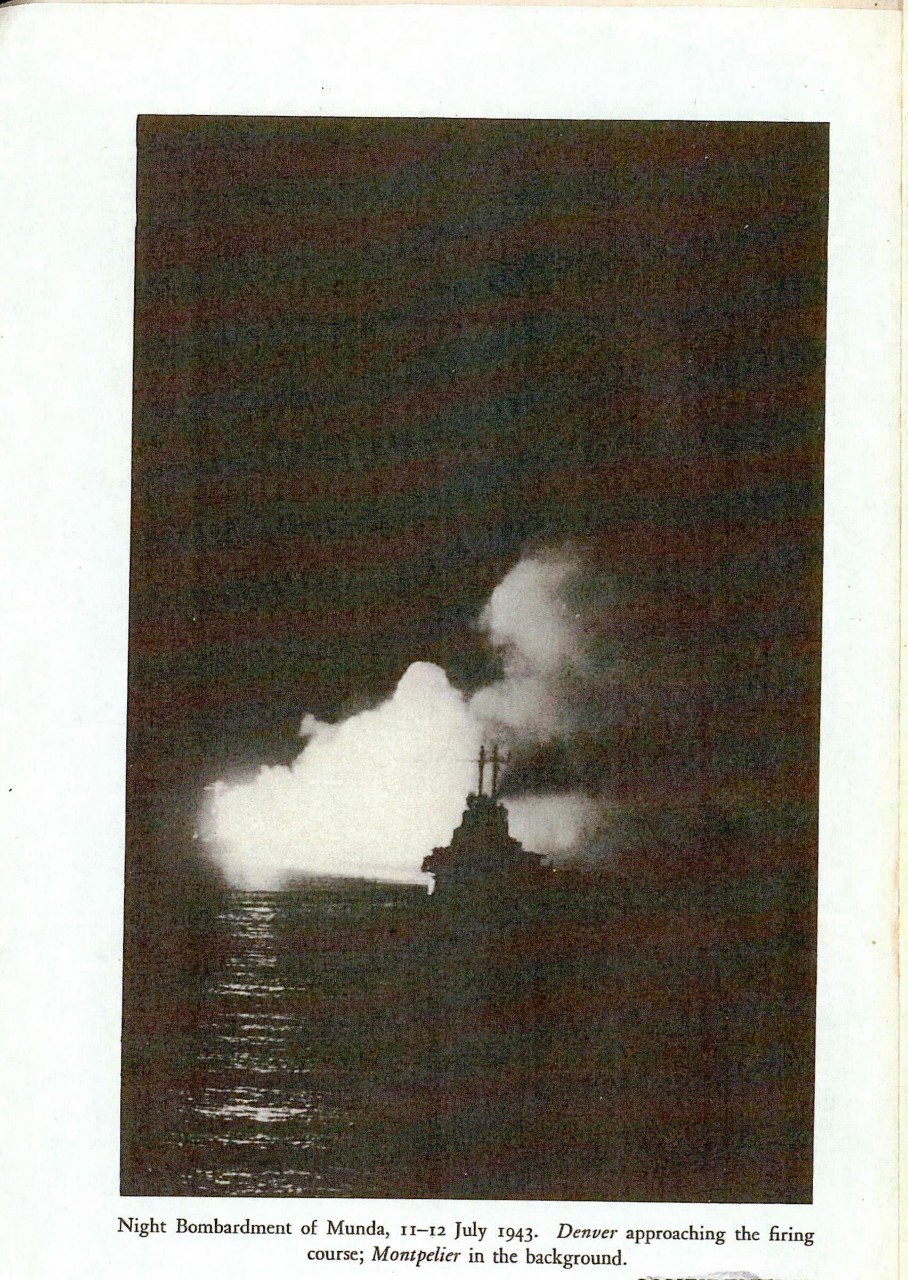

| Bombardment, Night 11-12 July 1943 | 32 |

| Battle of Kolombangara, Night of 12-13 July 1943 | 34 |

| Introduction | 34 |

| The Approach | 36 |

| First Phase | 39 |

| Second Phase | 39 |

| Third Phase | 42 |

V

| Page | |

Battle of Kolombangara--Continued |

|

| The Retirement | 43 |

| Comments and Conclusions | 44 |

| Rescue of the Helena Survivors, 16 July 1943 | 46 |

| Destroyer Operations in Kula Gulf, Night 17-18 July 1943 | 48 |

| Bombardment of Bairoko, Night of 23-24 July 1943 | 49 |

| Bombardment of Lambeti Plantation, Night of 24-25 July 1943 | 51 |

| PT Boat Operations, 23 July-5 August 1943 | 55 |

| Air Operations During the Munda Campaign | 57 |

| The Fall of Munda | 58 |

| Appendix I: Task Force Organization | 60 |

| Appendix II: Ground Force Organization | 66 |

| Appendix III: Symbols of U.S. Naval aircraft | 67 |

| Appendix IV: Designation of U.S. Naval aircraft | 69 |

| Appendix V: List of published Combat Narratives | 72 |

VI

Operations in the New Georgia Area

21 June – 5 August 1943

The final offensive to clear the Japanese from the New Georgia area, which opened on 30 June, was the first continued land, sea, and air effort undertaken by our forces in the Solomons since the capture of Guadalcanal.

The New Georgia group, lying 200 miles northwest of Guadalcanal, extends in a northwesterly-southeasterly direction for a distance of 150 miles. Most of the islands are mountainous and are of volcanic origin. Off their coasts barrier islands and reefs have formed lagoons which in times past were the habitat of a people known throughout Melanesia for their maritime aggressiveness.

As early as August 1942 there were reports of Japanese activity in this area. At first the Japanese made use of numerous hideouts and dispersal anchorages and established staging points in the vicinity for the purpose of ferrying troops and supplies to Guadalcanal. Later, after their failure to gain command of the air over Guadalcanal in November 1942, they began to construct an airdrome near Munda Point on the southwest coast of New Georgia Island. The location of Munda Point is such as to render it almost immune to invasion from the sea. There are only two approaches; one from the north through Diamond Narrows, a deep but very narrow channel; the other from the west across Munda Bar, which has only two fathoms of water and is therefore dangerous during a heavy sea or a swell.

So cleverly did the Japanese conceal the construction of their airdrome that our reconnaissance failed to detect any signs of activity there until the project was well under way. The Japanese strung heavy wire cables between the tops of the palm trees in such a way as to form a net. The trunks were then cut out from under the branches, which remained in place supported by the cables. After the runway was completed, this

1

camouflage was rolled back, and further attempts at concealment were abandoned. Shortly before the completion of the Munda airfield on 29 December, the Japanese began to build a second air base near the mouth of the Vila River on the southern tip of Kolombangara Island.

PRELIMINARY BOMBARDMENTS OF MUNDA 1

The threat offered by these bases to our position on Guadalcanal was obvious. Beginning with 3 December (the day the Munda field was discovered), aircraft from Guadalcanal made repeated attacks, bombing and strafing gun emplacements, buildings, and runways. During the ensuing three months, our fliers conducted more than 80 raids. Some of these promised spectacular success; yet none interrupted Japanese use of the installations for more than a day or two.

On the night of 4 January, a task group of cruisers and destroyers left Guadalcanal and stood up toward Rendova Island in the first of a series of naval bombardments of Munda. Shortly after midnight, they opened fire on predetermined targets. Observers agreed that the bombardment was the most destructive that had been delivered against the Japanese up to that time. It was disappointing subsequently to learn that the shelling had proved little more effective than the bombings which had preceded it. On the afternoon of 5 January, less than 18 hours afterward, hostile aircraft were operating from the field again.

Subsequent bombardments of enemy air bases in the New Georgia Islands were hardly more successful. The Vila-Stanmore district on Kolombangara was shelled by a task group on the night of 23-24 January. On the nights of 5-6 March and 12-13 May, there were simultaneous surface bombardments of Munda and Vila-Stanmore. The chief value of these operations was in neutralizing airdromes and destroying enemy supplies and personnel.

THE OCCUPATION OF THE RUSSELL ISLANDS

After their evacuation of Guadalcanal, early in February, 1943, the Japanese continued to strengthen their positions in the Solomons-Bismarcks area and in New Guinea but displayed no intention of resuming the offensive. Immediately after the fall of Guadalcanal, however, Ad-

-------------------

1 See Combat Narrative “Bombardments of Munda and Vila-Stanmore, January-May 1943” (Solomon Islands Campaign: IX).

2

miral Halsey set in motion plans for occupying the Russell Islands 2 so that they might be used as a staging point for our advance into New Georgia. Supported by a strong covering force (Cruiser Division 12 and attached destroyers) the first echelons made unopposed landings at three different points in the Russells at about dawn on 21 February and proceeded at once to begin construction of a radar station, a PT-boat base, and an air strip. A steady stream of men, supplies, and equipment was brought in nightly; by the end of February we had more than 9,000 men in the Russells, made up principally of units of the 43rd Division, the 3rd Marine Raider Battalion, the 10th Marine Defense Battalion, the 35th Construction Battalion, and other Naval Base personnel operating under Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner as ComAmphibForSoPac.

LOGISTIC PREPARATIONS

Even before the Japanese had been driven out of Guadalcanal, Naval construction battalions were at work on additional fighter strips to improve dispersion and relieve congestion on Henderson Field. Other units were constructing an additional bomber field on Koli Point. By the time that preparations had been completed for the final assault against Munda,we had available four airfields on Guadalcanal and two in the Russells, 3 all completely staffed and with maintenance units attached.

After the Japanese were expelled from Guadalcanal our situation was improved by the establishment of bulk gasoline stowage facilities and tank farms and the construction of a submarine fill line, which brought aviation gasoline direct from tankers moored off Koli Point to the tank farm. By July there were thirty-five 1,000 barrel tanks and one 10,000 barrel tank for aviation gasoline in seven groupings at Koli Point and stowage facilities of somewhat smaller proportions at Lunga Point. At the airfields and close by were additional stores of motor gasoline and diesel oil.

Fueling and ship-repair equipment at Tulagi and Port Purvis was also improved. In the Tulagi area a seaplane base was developed at Halavo;

----------------------------

2 A small group of islands situated about 30 miles northwest of Guadalcanal.

3The four airfields at Guadacanal were: (1) Henderson Field, a base for all light and some heavy bombers and most short range search planes, (2) Fighter No. 1, the main base for fighter aircraft (principally Marine and Navy fighter planes), (3) Fighter No. 2, the main base for Army and New Zealand fighter planes, (4) Carney Field, used principally for heavy and medium bombers and long range search planes.

North Field in the Russells was used as a base for both light bombers and fighters; South Field was limited to fighters.

3

a PT operating base at Sasapi (Tulagi Island), Calvertville (Florida Island), and Makambo Island; an LCT repair base at Carter City (Florida Island); and an amphibious boat pool at Turner City (Florida Island). During June 1943 supplies for the New Georgia campaign were moved up to the Russell Islands from the stock piles in the Guadalcanal area. 4 The primary bases for the invasion were located, however, at Noumea in New Caledonia and Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides.

ESTIMATES OF ENEMY STRENGTH

Enemy naval forces in the Solomons area were estimated at two destroyer divisions, one submarine division, and twelve non-combatant ships. Available forces in the Bismarck Archipelago were believed to consist of one light cruiser, five destroyers, seven submarines, and twenty-five non-combatant ships. Most of the Japanese naval strength was concentrated at Rabaul and brought into the Solomons by way of anchorages in the Shortlands and advanced bases on Bougainville.

Enemy ground strength in the Solomons was placed at 40,000 men: 8,000-10,000 of these were on New Georgia, fully a third of them in the Munda area; 5,000-7,000, including laborers, were situated on Kolombangara; the remainder were scattered about at other points.

In addition to the airfields at Munda and Vila, which have been previously mentioned, the enemy had fields at Buka, Kahili, Ballale, and Kieta, as well as seaplane bases at Shortland-Faisi, Rekata Bay, and Soraken. Furthermore the fields at Lakunai, Rapopo, Vunakanau, and Kavieng in the Bismarck Archipelago and the seaplane base at Rabaul were available for staging aircraft and for air operations in the Solomons. Estimates of Japanese air strength in the Solomons-Bismarck area indicated that the enemy had approximately 380 planes available for combat purposes. In addition he could draw on a force of slightly less than 100 combat planes in New Guinea in order to replace his combat losses in the Solomons.

PLAN OF ATTACK

The plans for the New Georgia operation were discussed in conferences held on Admiral Turner’s flagship, the McCawley, during the last

------------------------------

4 23,775 drums of fuel and lubricants, 13,085 tons of gear, and 28 loaded vehicles were among the items concentrated in the Russells for this purpose.

4

two weeks of May. On 3 June Admiral Halsey issued the basic operation plan. D-day was set for 30 June.

On that day our forces were to make simultaneous landings at several points on Rendova Island and on New Georgia at Viru Harbor, Segi Point, and Wickham Anchorage. The landings on New Georgia were to be made without preparatory bombardment, but it was anticipated that call and counterbattery fire might be required. These landings were designed to take and develop positions as bases for further operations. It was planned to construct a landing field on Segi Plantation, to develop Wickham Anchorage and Viru Harbor as protected staging refuges for small craft, and to create operating facilities for motor torpedo boats in Rendova and Viru harbors.

The real thrust against New Georgia was to come from Rendova. At the first opportunity troops from there were to move across Roviana Lagoon and land east of Munda to capture the airfield in a quick stroke. This movement was to be covered by preliminary landings on Sasavele and Baraulu Islands, which would secure the Onaiavisi Entrance to the Lagoon. The attack from Rendova was to be accompanied by the seizure by the by the seizure of enemy positions in the Bairoko-Enogai area, in order to prevent the Munda garrison from being reinforced from the north. This was to be accomplished by troops from the Russells. As soon as the Munda and the Bairoko-Enogai areas were occupied, preparations were to be made to capture the Vila- Stanmore position on Kolombangara.

TASK FORCE ORGANIZATION

The plan provided for three major task forces. 5 The first of these, Task Force TARE, was initially under the command of Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, who was relieved on 15 July by Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson after the main landing operations were completed. Task Force TARE was subdivided into two groups, the first of which, the Western Force, conducted the operations in the Rendova-Munda area. The other group, known as the Eastern Force, was responsible for the landings and subsequent operations at Viru, Segi, and Wickham Anchorage. The second task force, acting under the direct command of Admiral Halsey, was to cover the operation and furnish

--------------------------------

5The composition of these forces is given in Appendix I. In the interest of security task force numbers have been omitted. Flag symbols for the first letter of the surnames of commanding officers have been substituted.

5

fire support. The main air support was rendered by task Force FOX (South Pacific Air Force) operating under the command of Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch. Its principal duties were to conduct reconnaissance and striking missions, provide direct air support during landings and on other occasions as requested, and furnish liaison and spotting aircraft. Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, as commander of aircraft in the Solomons, had tactical command initially of that portion of the task force which operated from Henderson Field and other bases in the Solomons. 6

PRELIMINARY MOVEMENTS

For four days before the landing, Munda was heavily attacked by Navy bombers. On the night of 29-30 June, as a prelude to the New Georgia movement, a task group of light cruisers and destroyers (CL’s of the 12th Cruiser Division, Montpelier, Denver, Columbia, and Cleveland, and DD’s Philip, Renshaw, Waller, and Saufley) 7 under the command of Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill, steamed up the Slot and bombarded the Vila-Stanmore area on the south coast of Kolombangara and the Buin-Shortland area two hundred miles beyond, near the southeast end of Bougainville Island. As a part of this operation, a mine detachment consisting of the Preble, Gamble, and Breese, led by Capt. William R. Cooke, Jr., in the Pringle, laid 336 mines off Shortland Harbor between Alu and Munia Islands.

The purpose of this operation was: (1) to disrupt temporarily enemy surface raids out of Buin via the Shortland route during the early phases of our New Georgia operations; (2) to lengthen the Japanese surface routes to New Georgia; (3) to place a suitable surface force in position to cover our New Georgia landings; (4) to provide a diversion for the New Georgia movement; (5) to reduce temporarily enemy air strength and installations on Ballale; and (6) to damage enemy installations in the Shortland-Faisi area.

The Bombardment Group left Havannah Harbor (Efate) on 27 June, effected a rendezvous with the Mine Detachment at Tulagi, and departed from there at 1330 8 on 29 June, proceeding up the Slot. At 1800 in obedience to signal the Task Group went to general quarters and remained continuously at battle stations until 0819 the following morning This

-----------------

6Admiral Mitscher was relieved by Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining, USAAF, on 5 July 1943.

7Names of commanding officers of ships may be found in Appendix I.

8All times are Zone “L” unless otherwise specified.

6

protracted period had been anticipated, and special provisions were made to insure that all hands should receive the maximum amount of rest and sleep during daylight of 28 and 29 June. During the approach, in order to alleviate the stifling effects of Condition AFIRM, hatches on the Denver were systematically opened, a battle ration was served between 2100 and 2200, operating personnel were relieved from time to time when practicable, and all hands otherwise were allowed to stand easy at their battle stations. The bombardment procedure had been rehearsed during dawn and dusk alerts on the two previous days. Final rehearsal in detail was conducted shortly after going to general quarters.

At sunset the destroyers Renshaw and Waller were sent ahead to bombard the Vila-Stanmore Plantation on Kolombangara Island. The Shortlands were 231 miles beyond our then most advanced base in the Russells. In view of this fact it seemed almost impossible to avoid detection by enemy planes, coast watchers, or submarines before nightfall, or, in any case, before our arrival at the objective. Therefore a diversionary bombardment to conceal our real objective seemed necessary if we were to achieve any degree of surprise. At 0015 on the following morning the Renshaw and Waller rejoined after carrying out their mission successfully. The bombardment had been plainly visible from the bridge of the Montpelier 28 miles to the northward. Enemy fire, from the northeast coast of Kolombangara, was slow and deliberate.

The remainder of the approach was uneventful. Three enemy destroyers had been sighted by a Black Cat in Blackett Strait on the previous night. Reports of enemy sightings during the day gave rise to the belief that there were seven enemy destroyers and perhaps two heavy cruisers and one light cruiser in the Shortlands area. It was reassuring to discover that the weather became increasingly foul as the ships proceeded up the Slot. Occasional rain squalls merged into a solid front, and the visibility decreased almost to zero. Less cheering was information that because of the bad weather General MacArthur’s forces had canceled a heavy air raid on Rabaul, along with strikes which had been planned for that night against Kahili, Ballale, and the Faisi float-plane base. These strikes had been intended to neutralize enemy air bases during our retirement from the area. So long as the adverse weather conditions continued there was assurance against any Japanese planes taking off. If on the other hand the front lifted before morning, enemy air attacks in force were to be expected.

7

The final approach of the two task units was made at reduced speed in order to give better protection against enemy observation of wakes as well as to permit time for the very accurate navigation required. The mining operations were started at 0127 (30 June) and were completed before the bombardment began. Five minutes before reaching the firing bearing, effort was made by each cruiser to establish contact with her spotting plane. In view of the weather conditions there was little likelihood that this could be done, but as it was written into the plan it would have been necessary to break TBS silence to cancel it.

The bombardment commenced at about 0154; targets were assigned as follows:

Montpelier,Poporang Island.

Saufley, Poporang Island.

Columbia, Faisi Island.

Cleveland, east end of Shortland (Korovo).

Renshaw, east end of Shortland Island (north of Kulitanai Bay).

Phillip and Waller, targets of opportunity.

Denver, Ballale Island.

The bombardment lasted for about 15 minutes and was conducted in a downpour of rain, accompanied by lightning and strong southeasterly winds. Our own tracers disappeared just beyond the muzzles of the guns. Neither the damage caused by the bombardment nor the results of the mining operation could be determined visually. Many observers heard explosions distinct from our own gun fire and saw flashes which were not lightning.

Notwithstanding the fact that no fighters9 were available exclusively to cover the retirement of this force, withdrawal took place without casualty to ships or personnel. The course (south of the Solomons) was planned in such a way as to give the enemy the impression that it was to follow the route through the Slot and likewise to take advantage of such air coverage as would be afforded by flights of friendly planes from Guadalcanal and the Russells. All along the west coast of Vella Lavella, Ganongga, and New Georgia, heavy black rain clouds hung almost at masthead height.

--------------------

9 They had been requisitioned for scheduled strikes and the coverage of the Rendova landing the following morning.

8

Dawn broke with a clear sky to the south and west, but by heading in close to land, where the heavy clouds still persisted, our ships escaped detection. At daylight seven P-38’s, made available by the cancellation of night strikes, appeared. Other friendly planes joined them off Tulagi, and the Task Group stood out through Sealark Channel en route to fueling rendezvous south of San Cristobal.

In spite of the success of the operation, Rear Admiral Merrill expressed the opinion that simultaneous bombardment and mine laying operations were of decreasing value except in the forward enemy-held areas where the Japanese were unable to maintain adequate sweeping services:

“Three such combined operations have been undertaken recently by South Pacific surface forces, of which the first-laid mine field only is believed to have produced a considerable bag of enemy ships. It is felt that each bombardment suffered by the enemy will alert him to the immediate need of extensive sweeping prior to initiating any ship movements in the area involved. For this reason it is believed that mining and bombardment henceforth should, as a general rule, be undertaken separately.”

THE LANDING AT SEGI POINT, 21 JUNE 1943

The landing at Segi Point took place in advance of the main New Georgia operation as a result of reports that the Japanese were moving into that area. On 21 June, Companies O and P of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion made an unopposed landing at Segi from the APD’s Dent and Waters. While approaching the landing area both ships touched and rode over a shallow spot. Upon their return to Tulagi, the Dent was forced to go into drydock at Espiritu Santo, and the Waters also required slight repairs. On the following day, the APD’s Schley and Crosby arrived at Segi with Companies A and D of the 103rd Infantry and Acorn SEVEN Survey. Segi Point was held jointly by the Army and the Marines until 28 June when the Army took over. The construction of a fighter strip at Segi was begun on 30 June; by 11 July the field could be used in an emergency. Later in the campaign it was used as a fighter base.

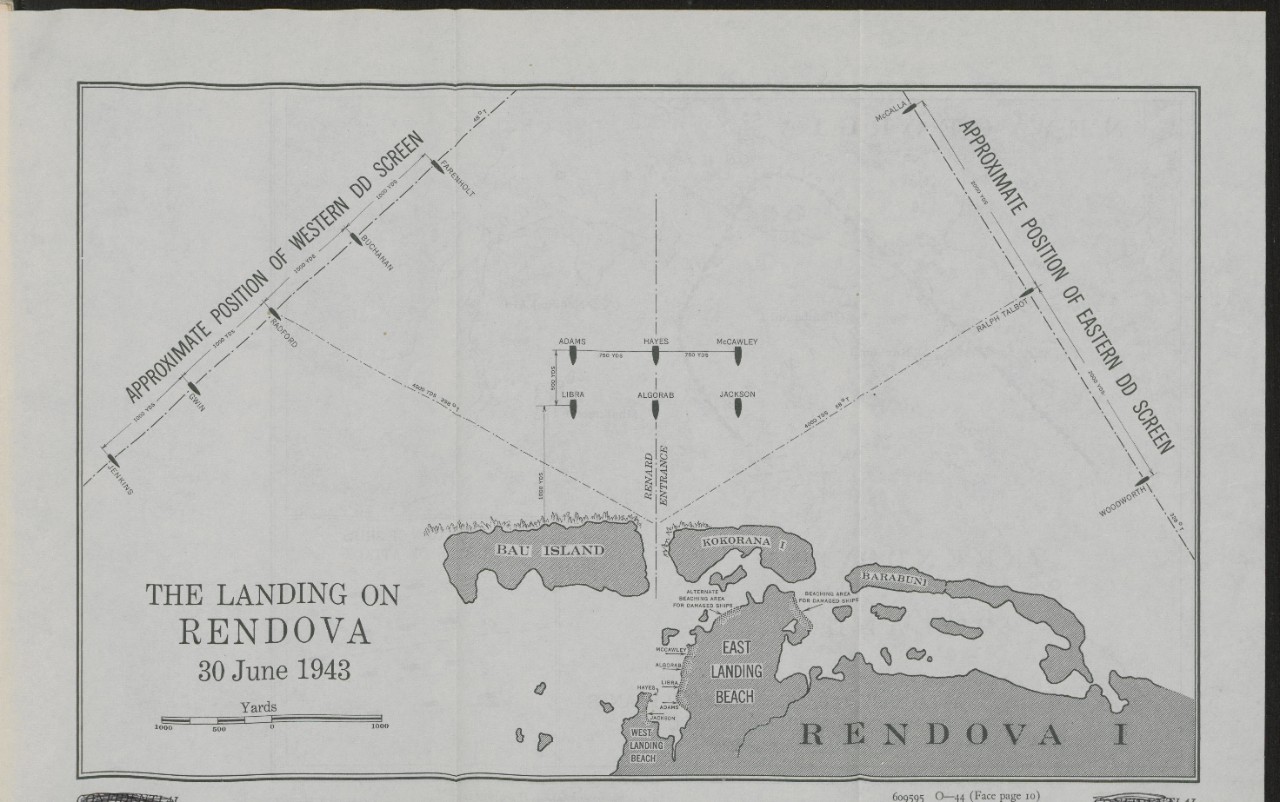

THE LANDING ON RENDOVA, 30 June 1943

The second landing in the New Georgia area took place at Rendova Harbor on the north side of Rendova Island, a boot-shaped islet about 20

9

miles long and 8 miles wide at its maximum, separated from New Georgia Island by only a few miles of water.

At 1000 on 29 June the transports to be used in this operation arrived at Guadalcanal from Efate, where ships’ crews and troops had been undergoing a final period of training in debarking and landing operations. At 1600 on the same day the task unit left Koli Point, Guadalcanal, and protected by low ceilings and poor visibility arrived off Renard Entrance of Rendova Harbor at 0620 on 30 June.

The first echelon of the Rendova movement was constituted as follows:

Advance Unit, Comdr. John D. Sweeney (ComTransDiv TWELVE):

Dent(F), Lt. Comdr. Ralph A. Wilhelm.

Waters, Lt. Comdr. Charles J. McWhinnie.

Transport Group, Capt. Paul T. Theiss (ComTransDiv TWO):

McCawley (FF) (Rear Admiral Turner), Comdr. Robert H. Rodgers.

President Jackson (F), Capt. Charles W. Weitzel.

President Adams, Capt. Frank H. Dean.

President Hayes, Capt. Francis W. Benson.

Algorab, Capt. Joseph R. Lannom.

Libra, Capt. William B. Fletcher, Jr.

Screening Unit, Comdr. John M. Higgins (ComDesDiv TWENTY-THREE):

Gwin (F), Lt. Comdr. John B. Fellows, Jr.

Woodworth, Comdr. Virgil F. Gordinier.

Jenkins, Comdr. Harry F. Miller.

Radford, Comdr. William K. Romoser.

Fire Support Unit, Capt. Thomas J. Ryan, Jr. (ComDesRon TWELVE):

Farenholt,(F), Comdr. Eugene T. Seaward.

Buchanan, Lt. Comdr. Floyd B. T. Myhre.

McCalla, Lt. Comdr. Halford A. Knoertzer.

Ralph Talbot, Comdr. Joseph W. Callahan.

Troops from the advance unit had already landed at dawn to secure the beachhead for the main occupation force which followed one hour later. Picking their way through the reefs, the troop transports entered the harbor and at 0642 began debarking men and materials. Two groups of destroyers were assigned the task of patrolling the two entrances of the harbor. Others screened the transports, ready to silence any shore gun which went into action. The boats leaving the McCawley were informed: “You are the first to land. Expect opposition.”

Our boats went ashore in the face of machine-gun fire from the beach. At a few minutes after 0700, the batteries on Munda Point opened up. The first salvo registered a hit in the engine room of the Gwin, the only destroyer which survived the Battleship Night Action of 14-15 November

10

1942. A near hit was also scored on the Buchanan. About the same time two other batteries on Baanga Island and one or two at Lokuloku to the eastward joined in.

The Buchanan and the Farenholt, veterans of the Battle of Cape Esperance, undertook the silencing of the enemy guns. Hits were obtained on the Munda Point area with the second salvo. Seven batteries in all were put out of action by the accurate gunfire of the two destroyers, which meanwhile varied their speed and heading so skillfully that the Japanese fire control problem was rendered practically insoluble. Exchange of fire between shore batteries and screening destroyers continued intermittently throughout the day.

By 0730 all troops except ship working details had been landed. Within two hours from the time of initial debarkation our newly emplaced shore batteries on Kokurana Island were shelling the enemy installations at Munda. The transports remained hove to in the debarkation area, completing their unloading. On two occasions, however, they had to get underway and move to the eastward under the threat of air attack.

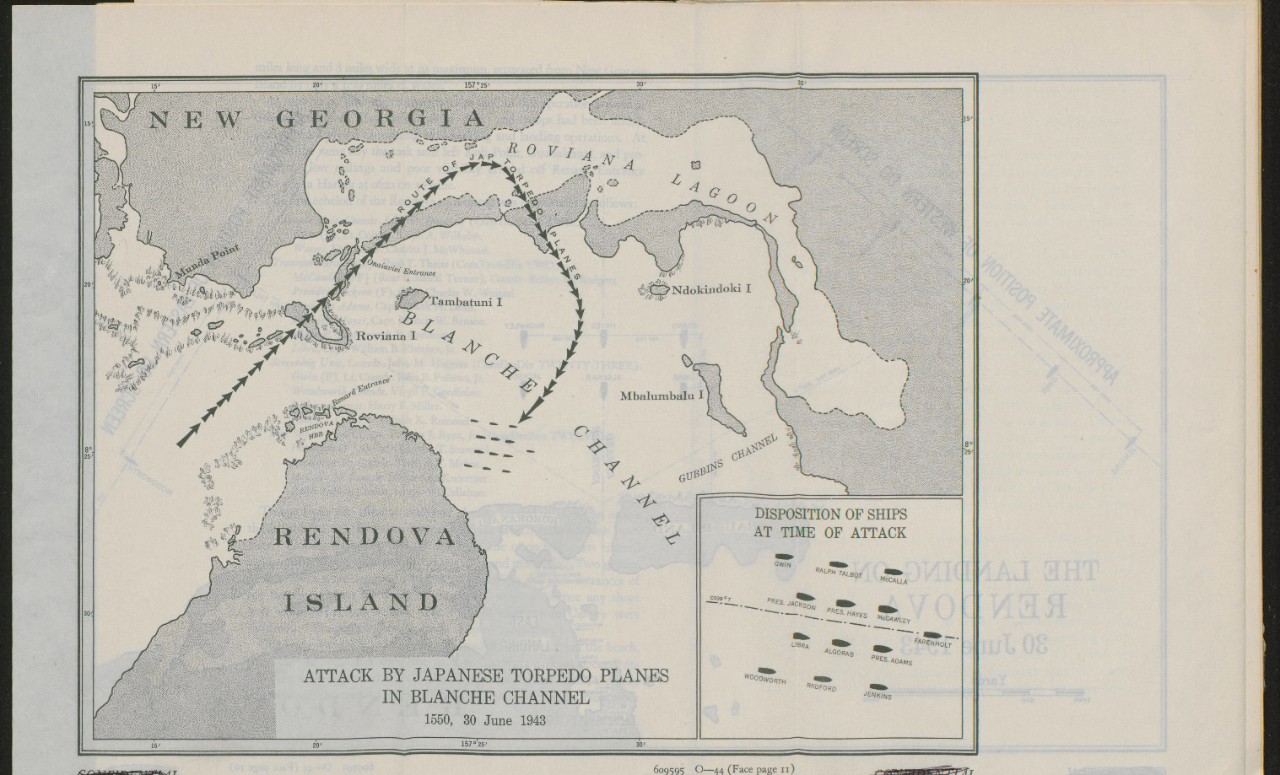

Throughout the landing operations a 32-plane combat air patrol was maintained by fighters from our bases in Guadalcanal and the Russells. Twice during the forenoon these planes drove off enemy aircraft which threatened our ships. Word of an impending attack was first received at 0857, and all destroyers closed transports to form an AA screen. The task unit steamed about in Blanche Channel until the all clear was given at 0950, when all units resumed their previous stations and disembarkation was continued. At 1105 air attack again appeared imminent, whereupon the task unit again ceased operations and proceeded into Blanche Channel until the all clear was given. In neither case did enemy planes come within range of our ships.

Unloading was completed by 1500 with a high degree of efficiency. The McCawley had discharged its cargo at the rate of 157 tons per hour while placing 1,100 troops on the beach. Orders were now given for the various units to gather in cruising formation and stand out through Blanche Channel to the southeast for the return to Guadalcanal. Within the hour, a group of 24 to 28 Mitsubishi type 96 torpedo bombers, escorted by an unknown number of Zero fighters, was sighted coming in over the northwest corner of New Georgia Island near Munda Point. As in the very similar enemy torpedo plane attack of 12 November 1942, the enemy bombers circled our formation, using land background, and then made

11

very low approaches at a speed hardly less than 250 knots. About one minute before the leading attack planes reached the screen, our formation executed “Emergency Turn 9” from a base course of 139 degrees.

All vessels opened fire, and hits were immediately scored. The bombers ignored their losses and came in with great determination, releasing their torpedoes at ranges approximating 500 yards.

Three planes in succession made drops off the Farenholt’s port beam. The first torpedo broached and passed ahead. The second missed astern. The remaining plane appeared to be about to attempt a suicide dive on the ship, but the pilot finally dropped his torpedo and sheered off ahead. The Farenholt’s commanding officer ordered full right rudder. A thud was felt on the bridge, and all hands waited for the explosion which seemed sure to follow. The seconds ticked by, and nothing happened. Either the vessel had been hit by a dud or the torpedo had run too short a distance to arm.

The McCalla was likewise bracketed by three torpedoes, one of which passed about 25 yards ahead, another 50 yards astern, and the third apparently passed under the ship. Flank speed and full right rudder were used to bring the course parallel to the torpedo tracks.

Our forces did not come through the attack entirely unscathed, however. The task group had just executed a ninety degree turn to the right and opened fire when a torpedo was seen approaching the port side of the 7,712-ton transport McCawley, flagship of Rear Admiral Turner. Her rudder was put over hard right, and the starboard engine was backed full. A moment later the torpedo struck amidships in the vicinity of the engine room. The McCawley lurched to port but immediately righted herself, still swinging to starboard with her rudder jammed hard over and all engines stopped. Admiral Turner ordered the cargo vessel Libra to take the flagship in tow, and the destroyers Ralph Talbot and McCalla were directed to stand by. Admiral Turner and his staff then went down the ropes and on board the Farenholt. Admiral Wilkinson remained aboard the McCawley in charge of the salvage crew.

As a result of the first explosion a hole was opened in the ship’s side about 18 to 20 feet in diameter extending from about frame 87 to 93. The frames between were carried away, and shell plating was blown outward with very ragged edges. All watertight doors remained intact, however. About 30 seconds after the initial explosion, another detonation of lesser magnitude followed, probably as a result of the rupturing

12

of the compressed air tanks used in connection with the port main engine. In spite of the efforts of damage control parties the ship continued to settle aft.

By 1558 the attack was over; the action had lasted only eight minutes. Only two enemies planes survived the attacks of our protecting fighters and the antiaircraft fire of the ships, and they were shot down during retirement by our planes.

About an hour later, the McCawley was attacked by a group of 12 to 15 Aichi dive bombers, which broke through the overcast at a level of about 1,000 feet. Although the ship was now dead in the water, the salvage crew manned the guns so effectively that the enemy aircraft were driven off. By this time, however, it was apparent that the McCawley could no longer be kept afloat, so the McCalla eased alongside, and all hands were ordered to abandon ship. At 2002 the McCalla was ordered to prepare torpedoes for sinking the McCawley if the settling of that vessel should warrant it. The end came even more quickly than had been expected. At 2023 the doomed transport was struck by three torpedoes; thirty seconds later she sank stern first in 340 fathoms of water. At first it was believed that she had fallen prey to an enemy submarine. It has since been learned that the McCawley was sunk by friendly PT boats which mistook her for an enemy.

* * *

In spite of the loss of the McCawley, enemy air opposition to our landing operations at Rendova was not impressive. The first attack group consisted entirely of fighters. The main strike by coordinated dive bombers and torpedo planes did not take place until 1500. Except for the threat of strafing at 1100, our amphibious operations were unopposed from the air for nearly eight hours of daylight, and thus the early and more difficult phases of our landing and unloading operations were completed without air opposition.

Two reasons for this fact may be suggested. It was known that the principal Japanese striking force in this area was either maintained at or staged through Rabaul and only flown into Kahili in preparation for a major strike. There is also reason to believe that many Japanese carrier-type aircraft pilots in this theater were not trained in night takeoffs. These factors taken in combination offer the best explanation for the fact that there was a lapse of four hours between the initial sighting

13

of our force by a Japanese search plane and the arrival of the first wave of attacking enemy planes.

The McCawley was the only ship other than the destroyers equipped with radar. After she was torpedoed it was necessary for the other transports to place full dependence on destroyer radars and the fighter director ship for the location and identification of planes which could not be identified visually. The TBS circuit was particularly helpful in advising all units quickly in cases requiring prompt action before the attack was completed and afterwards.

The second echelon of the Rendova movement, consisting of four LST’s and five LCI’s under the command of Captain Carter in LST 354, escorted by the Farenholt, Buchanan, and Gwin, arrived at Rendova Harbor the following day. The beach at Kokoruna was satisfactory, although embarkation of troops and cargo was handicapped by rains and heavy mud. The East Beach of Rendova Harbor proved extremely unsatisfactory, however. The beaching had to be made at dead slow speed, and the vessels were unable to plow their way through the mud to the beach proper. Vehicles could be operated only with difficulty because of deep mud, and many had to be abandoned. This area was finally vacated, and the LST’s were diverted to the beach section opposite Pago Pago Island. In his report of the operation the task unit commander observed that “The selection of beaches for use by LST’s from air reconnaissance only cannot be satisfactory . . . . In planning future operations, every effort should be made to obtain reliable and actual information relative to beaches intended to be used by LST’s. Air photos are inadequate and even misleading thereby endangering the success of such an operation.”

* * *

Throughout July reinforcements of men and supplies were moved into Rendova on a daily schedule by our transport command. Between 30 June and 31 July, 28,748 personnel (25,556 Army, 1,547 Navy, and 1,645 Marines), 4,806 tons of rations, 3,486 tons of fuel, 9,961 tons of ammunition, 6,895 tons of vehicles, and 5,323 tons of freight were unloaded at Rendova by the Western Force of Task Force TARE. The success of the Rendova patrol in warding off Japanese attacks is attested by the fact that during the entire operation only three hits were registered on our ships by bombing and torpedo plane attacks and only one horizontal bombing attack reached the objective during daylight hours.

14

OTHER LANDINGS IN THE NEW GEORGIA AREA

Onaiavisi, 30 June 1943

Even before the first echelon had arrived at Rendova steps had been taken to secure the Onaiavisi Entrance to Roviana Lagoon in order to make possible landings east of Munda. At 0230 on 30 June the destroyer Talbot and the minesweeper Zane arrived off Onaiavisi with the Initial Landing Force and began to debark units of the 169th Infantry, 43rd Division, on Sasavele and Baraulu Islands adjacent to the Entrance. At the time of arrival the visibility was very poor with no moon and persistent heavy rain squalls. At 0257 while maneuvering on an approximate heading of 155 degrees T. the Zane ran aground on Dume Island. At 0631 after repeated attempts to clear the reef by twisting, the OTC received information from Admiral Turner by voice radio that the tug Rail was proceeding to assist. By 0845 all troops and provisions had been disembarked. While awaiting the arrival of the Rail, the Talbot made several attempts to extricate the Zane but had to abandon them because of impending air attack. Numerous unidentified aircraft were overhead; the Talbot began maneuvering to avoid them but was not molested. At 1248 the Rail hove in sight and in less than an hour and a half succeeded in freeing the Zane. The three ships proceeded to clear the area at once and took station astern of the main task group, which had by this time completed the landings at Rendova and was now passing through Blanche Channel en route to Tulagi. All three ships passed unscathed through the Japanese torpedo bomber attack at 1550. The Talbot and Zane took the attacking planes under fire.

At 0832 on the following morning two SC’s and one PC were detailed to act as a screening unit for the Zane while the Talbot proceeded into Tulagi independently. Inspection at Tulagi disclosed that both propeller blades of the Zane had been wrinkled, bent, and torn; the shafts were believed to be sprung and the sound dome damaged. Inasmuch as the service unit at Tulagi was unable to effect repairs, arrangements were made to tow the Zane to Espiritu Santo for necessary repairs.

On 2 July, a good beach was located at Zanana on the south coast of the New Georgia mainland six miles east of Munda, and a company of SoPacFor Scouts was landed there. That night the Scouts were reinforced by units of the 169th and 172nd Infantry. Assault boats from the Rendova Boat Pool, LCM’s, LCVP’s and LCP(R)’s, protected by

15

MTB’s, were used to convey the troops in a shore-to-shore amphibious movement from Rendova to Zanana via Onaiavisi Entrance. Combat patrols moved ashore and took up their positions along the Barike River, the Army’s line of departure. By 8 July all artillery and troops were in position for the jump-off against Munda.

Wickham Anchorage, 30 June 1943

The first landings in the Wickham Anchorage area were made at Oloana Bay at 0630 on the morning of 30 June. At 1812 on 29 June a task unit under Rear Admiral George H. Fort in the Trever, composed of the APD’s Schley and McKean and LCI’s 24, 233, 332, 333, 334, 335, and 336 left Wernham Cove in the Russell Islands and proceeded northwest toward Vangunu Island. On board the Schley and McKean were companies N and Q and 50 percent of the Headquarters Company of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion, 1st Marine Raider Regiment, attached to the 2nd Battalion, 103rd Combat Team of the 43rd Division.

At 0115 on 30 June as we were proceeding on a base course of 345 degrees T. a radar contact bearing 063 degrees T. at a distance of 8,400 yards was reported. At 0125 two flush-deck destroyer-type vessels bearing 065 degrees T. were sighted at a distance of 2,000 yards on a course which would intercept ours. Orders were given to change course, and presently the two unidentified vessels disappeared from sight.

At 0335 the task unit hove to off the west side of Oloana Bay. At 0345 embarkation of the first wave commenced under extremely hazardous conditions as a result of heavy seas, low clouds, and high wind. The outline of the beach was not readily discernible at any point. After one or two boats had been loaded it was learned by the APD commanders that they were lying off the wrong side of Oloana Bay. Both APD’s immediately moved approximately 1,000 yards to the east, and embarkation was resumed.

The first wave of boats was thrown into confusion as a result of LCI’s carrying Army personnel breaking into their formation. All attempts to regain contact were unsuccessful, so the coxswains were forced to guide their craft to the beach individually. Since they had not been provided with the course to the beach, they became widely separated and landed the troops along a stretch of seven miles of terrain to the west of the designated landing beach. Six boats were lost in the heavy surf.

The second wave from both APD’s landed at 0630, 0635, 0730, and 0805 on the designated beach, east bank. At 1000 all landing operations were

16

completed without opposition, and the task unit was ready to return to Purvis Bay.

Vura Village, several miles inland, had been designated as the objective in the original operations order, but after landing it was discovered that the main body of the enemy was situated at Kaeruka. In the fighting which followed, a force of 300 Japanese was wiped out. By 3 July our objectives in this area had been realized.

Viru, 1 July 1943

The landing at Viru was delayed for one day beyond the time originally planned because of the late arrival of the advance unit, which had been landed at Segi on 21 June and dispatched overland to Viru.

The first echelon of the Viru Harbor occupation unit under the command of Comdr. Stanley Leith arrived off Viru at 0610 on 30 June. The unit was organized as follows:

Advance Unit, Lt. Col. Michael S. Currin:

Companies O and P of the Fourth Marine Raider Battalion.

First Echelon, Comdr. Stanley Leith (ComMinRon 2):

Hopkins (FF), Lt. Comdr. Francis M. Peters, Jr.

Kilty (F) (Comdr. Robert H. Wilkinson, ComTransDiv 22) Lt. Comdr.

Dominic L. Mattie.

Crosby, Lt. Comdr. Alan G. Grant.

plus

One LCV towed by the Hopkins.

Landing Force, Capt. R. E. Kinch:

Company B, 103rd Infantry, reinforced by one-half Company D.

20th Construction Battalion.

Naval Base Units, including Boat Pool.

Battery E (less one platoon) Seventieth C. A.

The directive governing the operation provided that the landing force embarked in the ships was not to land until the enemy guns guarding the entrance to the harbor had been immobilized by the advance unit attacking from the direction of Segi. It was also provided that the commander of the occupation unit should disembark the landing force into boats and have it in readiness to send in at 0645. A message was received en route, however, that the Raiders had been delayed at Choi River near Nono, New Georgia, on 28 June by enemy action. It was then decided by the task group commander that the troops should not be disembarked into the boats until there was some indication that the advance unit was attacking Viru Harbor.

17

As soon as the task group arrived off Viru, attempts were made to establish contact with the advance unit by radio. These were continued for several hours without success. At 0703 a 3-inch shore battery opened fire, bracketing the Crosby with its first three shots. The ships returned

the fire but withdrew out of range, establishing patrol about 4,000 yards from the harbor entrance, a narrow passageway flanked by sheer cliffs 100 feet high.

18

At 1007 a dispatch was transmitted to Admiral Turner by the unit commander recommending that in view of the unknown position of the Raiders and the inadvisability of attempting a frontal assault without a simultaneous land attack, the embarked troops be landed at Nono Point at the mouth of the Choi River, so that they might proceed overland to Viru. This recommendation was approved, and the troops were landed accordingly. The Kilty, Crosby, and Hopkins then returned to base.

At 1700 on 1 July the capture of Viru by the advance unit was reported, and additional forces were able to land directly from seaward that night.

Rice Anchorage, 5 July 1943

On the morning of 5 July, after a twenty-four hour postponement, landings were made at Rice Anchorage on the north coast of New Georgia in order to make possible an advance on the Bairoko-Enogai area and thereby prevent the Japanese garrison at Munda from receiving reinforcements from Kolombangara. By this time our beachheads east of Munda were firmly established, and preparations were being made to advance on the airfields. The force involved in the landing operations consisted of a transport group made up of 7 APD’s (Dent, Talbot, Waters, McKean, Kilty, Crosby, and Schley) and the destroyer McCalla; a mine group composed of the Hopkins, Trever, and the destroyer Ralph Talbot; and a screening unit comprising the Woodworth, Gwin, and Radford. The landing force consisted of the 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry and the 3rd Battalion of the 148th Infantry, both of the 37th Division, and the 1st Marine Raider Battalion.

During the night of 4-5 July, in preparation for these landings, a task force of cruisers (Honolulu, Helena, and St. Louis) and destroyers (Nicholas, O’Bannon, Strong, and Chevalier) under Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth, bombarded enemy positions and gun installations in the Vila-Stanmore and Bairoko Harbor areas. The original plan called for a heavy concentration of fire on Enogai Inlet, but at the last moment this was abandoned upon instructions from the task force commander, because our reconnaissance photographs revealed no evidence of enemy shore batteries in the Enogai area. Since there was little possibility of surprise, the heaviest concentration of fire was reserved for artillery emplacements, instead of troop bivouac areas, which had been the principal targets in previous bombardments.

19

In contrast to previous bombardments of the area, this one gave rise to real opposition. Contrary to our expectation, the four cleverly concealed 4.9 inch guns of the battery at Enogai caused us more trouble than any other opposition during the bombardment. During the first leg of the bombardment, which opened at 0026 on 5 July, the cruisers and rear destroyers (O’Bannon and Chevalier) subjected the Vila target objectives to a heavy and extremely accurate fire. Salvos were employed at six second intervals. The bombardment plan called for firing 14 minutes without ceasing, on a course of 190 degrees T., checking fire long enough to change course 100 degrees to port and then firing for six or seven minutes on targets in Bairoko Harbor. Once the bombardment had commenced, however, enemy shore batteries forced some deviation from this plan.

As the flagship changed course to the northward after completing its bombardment of Bairoko only one destroyer ahead appeared upon the screen. Almost immediately the missing destroyer was identified as the Strong, and within a few moments she was located, on the starboard side of the Honolulu, dead in the water as a result of a torpedo hit received at 0043. The destroyers Chevalier and O’Bannon were detailed to conduct rescue operations, during which enemy shore batteries repeatedly illuminated the whole area with star shells and the three ships were subjected to accurate and intense fire from the beach, as well as to bombing by Japanese planes circling above them.

In going alongside the Strong, the Chevalier struck the sinking ship on her port bow, opening a hole in her own bow ten feet long and two feet wide at the level of the first platform deck. All damage was above the waterline, however, and did not seriously impair the operation of the ship. A 6-inch manila line was passed, and every effort was made to expedite transfer of personnel from the Strong, as she was settling fast. Before the Chevalier retired she managed to rescue seven officers and 232 men, roughly 75 percent of the crew, during a period of nine minutes. While the Strong was sinking, she was hit twice by one of the shore batteries. As she disappeared at 0123, at least four of her depth charges exploded below the forward part of the Chevalier, lifting that vessel nearly out of the water and rendering her radar and compasses inoperative. Several hours later the commanding officer of the Strong, Comdr. Joseph H. Wellings, was picked up by one of the screening destroyers of the transport group. He was on a raft with a small number of Strong

20

survivors and was suffering from concussion caused by the depth charges. Some of the Strong survivors were shell shocked, while others were blinded by fuel oil.

The source of the torpedo which sank the Strong is not definitely known. It may have been a submarine on the westward or northwestward side of the Strong or possibly two destroyers which are believed to have left Kula Gulf at high speed about 0040. Since only one ship was attacked and no other ships reported torpedo wakes, it is possible that the damage was inflicted by a two-man submarine.

While the Chevalier and O’Bannon were retiring from Kula Gulf they were fired upon by the screening group, which was now attempting to take the enemy shore batteries under fire. Although the Gwin and Radford attempted to triangulate the positions of the enemy shore batteries with some spotting assistance by the Ralph Talbot in the transport area, they had no success in silencing these batteries. When fired upon, the Japanese would cease firing, and as soon as our fire slackened they would resume fire.

At 0154 the Chevalier opened fire with her machine guns in the general direction of the O’Bannon. She was immediately asked what she was firing at. The reply was “a torpedo plane.” The O’Bannon later reported that she had observed no planes and had no signs of any on the radar screen.

In spite of the many shells which fell in the transport area there were no casualties. The Waters had her main truck shot away, and several of the other transports were hit by shrapnel but sustained no damage. At 0110, soon after the bombardment ceased, the landing operations began. The transports were unloaded into Higgins boats, each of which towed one 10-man rubber boat. The APD’s were unloaded first, followed by the DD’s and DM’s. As the APD’s were unloaded they stood up to the northward to form a screen.

The entrance to the beach was over a narrow, shallow bar. Many of the boats touched bottom in crossing it, so that it became necessary to decrease their normal load. Moreover, the beach was so short that only four were able to unload at the same time. As a result boats were jammed up in the Wharton River all during the landing, waiting their turn to unload. Further confusion and misunderstanding resulted from a last minute change in the plans for debarkation made by the task unit com-

21

mander after the troops had been embarked. Not only was the change not properly disseminated, but it also dislocated the Marines’ tactical plan of attack when the beach had been reached.

During the entire operation the Enogai battery fired intermittently at the supporting destroyers. The enemy appeared unaware of the presence of the landing force until daylight. At 0559 all transports were

22

ordered to clear the area. Only two percent of the troops remained to be landed. The volume and accuracy of fire from the shore batteries was rapidly increasing, and it seemed dangerous to expose the entire force to possible air attack merely to get these few men ashore. Apart from the loss of the Strong and damage to the Chevalier, the operation had been carried out according to plan.

BATTLE OF KULA GULF, 5-6 JULY 1943

The Approach

On the afternoon of 5 July while returning from its bombardment mission of the evening before, the task group commanded by Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth in the Honolulu received orders to reverse course and proceed northward to the Kula Gulf area in order to intercept the Tokio Express on its nightly run from Bougainville. The destroyers Radford and Jenkins were assigned to the task group in place of the Strong and the Chevalier. Otherwise the ships were the same which had bombarded Vila-Stanmore and Bairoko on the night of 4-5 July.10 In compliance with this order the task group steamed up the Slot via Indispensable Strait, picking up the Radford and Jenkins en route. This was the most direct route and would save fuel, in which all ships were low. It would also avoid the friendly ships which were to be expected off Guadalcanal.

Shortly after passing Visuvisu Point the OTC ordered cruising speed reduced first to 27 knots and then to 25 knots in order to conserve fuel. No information had been received from our Black Cat search planes, and one of them had reported that he was returning to base because of the weather. The night was very dark with no moon. At its best, visibility was no more than two miles. The task group had been directed by dispatch to retire at 0200 6 July in case contact had not been made with the Tokio Express by that time.

At 0136 while moving on a course of 2900, bearing about 3210, distance 26,000 yards from Visuvisu Point, the Honolulu made a radar contact with a group of ships off the northeast coast of Kolombangara bearing about 2200, course 3150, distance 22,000 yards. Admiral Ainsworth or-

-------------------

10 See p. 19.

23

dered the task group to adopt battle formation in single column, with the Nicholas and O’Bannon in the van followed by the cruisers Honolulu, Helena, and St. Louis in that order, and the Jenkins and Radford in the rear. At 0142 our formation made a simultaneous 600 turn to the left to close the enemy. Eight minutes later a simultaneous 600 turn to the right placed the formation on a firing course of 2920. Range at this time was approximately 10,000 yards. After this maneuvering the van destroyers found themselves 5,000 yards ahead of the flagship on her disengaged bow, and were thus prevented from delivering an early torpedo attack without endangering the cruisers. The rear destroyers were unable to form column before the first turn signal was executed, and consequently the Jenkins blanked the fire of the Radford, thus keeping her from engaging the enemy during the first phase.

At the time the enemy appeared to be in two groups, which may have consisted of five and four destroyers respectively, although the task group commander is of the opinion that several cruisers were involved. The sections were 6,000 - 8,000 yards apart. Admiral Ainsworth considered attacking both simultaneously but decided that the interval between them was too great. Consequently he determined “to blast this (the leading) group first, reach ahead, then make a simultaneous turn and get the others on the reverse course.” This plan was carried out precisely.

First Phase

The order to commence firing was given at 0157 at a range of about 7,050 yards, which was somewhat nearer than the OTC desired. The van destroyers as well as the cruisers opened fire immediately but the rear destroyers held their fire. The leading enemy group also made a change of course to the westward about this time, so that the range rate was approximately zero. At the opening of the battle this group was heading west in close formation on a line of bearing about 500 T. thus exposing itself to enfilade fire.

The gunfire on the first leg lasted slightly more than five minutes. Approximately 1,500 rounds of 6-inch, plus a fairly heavy fire from the 5-inch/38 batteries of the van destroyers and the Helena, were poured into the first group of enemy targets. In consequence of the fact that our fire enfiladed the enemy’s formation, our ships concentrated on the nearest enemy vessels. The Honolulu fired on three, shifting fire from one to the other when targets were seen to be in flames. The main

24

battery of the Helena fired on two targets in succession, which disappeared from the radar screen. Most of the other vessels were using salvos, but the Helena had begun continuous fire. She had to employ ordinary smokeless powder, because all but a small amount of her flashless powder had been expended during the bombardment of the previous night. Her rate of fire was so rapid that the gun flashes lit up the whole ship, with the unavoidable result that she presented an excellent target. The St. Louis fired first on probably the same target as the Helena, then shifted to her own normal target when it appeared on the screen. Both Japanese ships appeared to have ceased firing and were left burning.

The destroyers Nicholas and O’Bannon on the western end of the line and the Radford on the eastern end were firing on the same targets as the cruisers when opportunity offered. For several minutes the Radford was kept from joining in because the Jenkins blanked her fire. The Jenkins was the only one of the destroyers which fired torpedoes during this phase, but she did not fire her guns during the engagement.

At 0203 the OTC executed a simultaneous turn of 180 degrees to the right. The van destroyers now became the rear destroyers and vice versa. A few seconds before its execution the Helena, veteran of 12 engagements with the enemy in the South Pacific, was struck on the port bow by a torpedo, followed in about ninety seconds by a second, and about one minute later by a third. Her bow to abaft No. 1 turret was blown off. The remaining part of the ship was broken in the middle at about No. 2 stack. None of our other ships was aware that she had been torpedoed and had fallen out of formation until some time later. Her commanding officer was not immediately aware after the first hit that the bow was completely gone, and the ship continued through the water at high speed, without any bow, until the second hit 1 1/2 minutes later.

Second Phase

During the second phase of the battle our task group proceeded on an easterly course, firing as targets presented themselves. At 0207 a Turn 3 to course 142 degrees was executed to close the targets. It was at about this time that a dud torpedo hit the St. Louis on the starboard side. Between 0210 and 0212 the Honolulu resumed fire on a damaged target in the first group at a range of 7,600 yards with excellent results. Between 0213 and 0215, both the Honolulu and St. Louis fired effectively on another damaged target until a 6 Turn to course 082 degrees was executed and

25

the targets drew too far aft. Meanwhile the Radford had fired a spread of four torpedoes at 0210, apparently without results.

Targets in the second enemy group, now coming up fast on northerly courses, were first taken under fire at 0217. The leading target, which appeared to be a three - or four-stack cruiser, was hit by the first salvo, and the target quickly disappeared from the screen. At 0222 the O’Bannon fired five torpedoes at a retiring target in the second group at a range of about 10,000 yards. The task group was again drawing away from the target area; at 0227 fire was therefore checked, and a Turn 15 was executed to bring the force around to the westward again on a course of 262 degrees. By the time our ships completed this turn, all the pips had disappeared from the screen or had been tracked into the beach on Kolombangara Island. All the members of the second group appear to have been taken under fire by more than one ship.

At 0241 “Turn 3” to course 292 degrees T. was executed. At 0242 the Nicholas fired a half-salvo spread of five torpedoes, target bearing 206 degrees, range 5,000 yards, and opened fire with guns. The target, probably a crippled destroyer, disappeared from the radar screen. At 0250 the OTC gave the order to “cease firing” as no other enemy ships were in sight on the radar screens except one which had apparently run aground near Waugh Rock. The formation now reached ahead toward the entrance of Vella Gulf, and the Nicholas was directed to make a radar sweep into the mouth of that Gulf for any additional enemy ships. The Radford was instructed to do likewise for the Kula Gulf area. Both searches led to negative results. At 0310, therefore, the OTC executed a Turn 18 and headed back for Kula Gulf. During this period (i.e. at 0255) the Jenkins fired two torpedoes at a target which was later believed to be a “phantom” inasmuch as it appeared close aboard visually on the heretofore disengaged northern side of the line but did not appear on the SG screen. While our ships were passing through the waters where the first engagement had been fought, the bow of a ship was sighted standing vertically out of the sea. Investigation by a destroyer disclosed that the vessel was the light cruiser Helena, first U. S. cruiser to be sunk since the torpedoing of the Chicago in January.11 Nothing further was encountered by the cruisers, which at 0327 changed course to 090 degrees and began retirement down the Slot in company with the O’Bannon and Jenkins. The Nicholas and

-----------------

11Admiral Ainsworth apparently first became aware that the Helena had fallen out of formation at about 0219, after the Helena had failed to acknowledge a series of maneuvering signals.

26

Radford under Captain McInerney were directed to remain behind and pick up the survivors of the Helena.

Third Phase

The Nicholas and Radford slowly nosed their way into the midst of the oil-soaked crew, who were scattered over an area a mile square. The men were singing and acting very much as if they were participating in a peacetime drill. Some were in life rafts; others were swimming separately; many had flash lights and were blowing whistles. For three hours the rescue operations were carried out almost in the direct path of enemy ships returning from Kula Gulf to their bases in the Buin-Faisi area. Constant reports of torpedoes, torpedo wakes, and submarines were received. With the approach of daylight enemy aircraft were reported to be in the vicinity.

At 0403, while in the midst of rescue operations, the two destroyers made radar contact at a distance of 16,800 yards with a large enemy ship bearing 274 degrees moving at high speed and closing. Both ships had to clear survivors from their sides, get boats clear, and make speed to engage the enemy. ComDesRon TWENTY_ONE informed the Radford that the Nicholas would stand between the enemy ships and the Radford so that the latter might continue the rescue work. The enemy ship or ships moved in to about 13,000 yards, then reversed course and stood to the northwestward before coming within effective gun or torpedo range. It is thought to have fired torpedoes, as high-speed propeller noises were picked up on the Radford’s sound gear. Both vessels returned to the survivor area and resumed rescue operations. Upon receipt of information of an enemy contact, Admiral Ainsworth had reversed course at 0412 and headed back for the scene of action. At 0429 he resumed retirement when informed by Captain McInerney that there was no further enemy contact.

At 0412 as the Nicholas and Radford were returning to the survivor area to resume rescue operations, the Radford detected two large ships standing out of Kula Gulf. The Radford was directed to continue rescue operations while the Nicholas attempted to locate and attack the target. At 0433, after failing to locate these contacts, the Nicholas returned to the survivor area.

At 0515 the Radford made radar contact with more enemy ships coming out of Kula Gulf. Both ships had to discontinue rescue operations

27

once more, clear their sides, and prepare to engage the enemy. At 0522 the Nicholas fired torpedoes at an enemy target bearing 178 degrees, distance 7,950 yards, course 315 degrees, speed 30 knots. The target closed to 5,000 yards, and the Radford had to maneuver to avoid enemy torpedoes. At 0530 the Radford fired four torpedoes at the same target, bearing 210 degrees, distance 6,000 yards, course 300 degrees, speed 25 knots. Both ships reported underwater detonations which by time of run might have been hits from their torpedoes. At 0533 both ships changed their course to 310 degrees in order to close the enemy then at about 8,000 yards. At 0534 the Nicholas and Radford opened fire; the Nicholas also illuminated with star shells. Two enemy ships were observed, the larger of which appeared to be a four-stack cruiser. Salvos were rocked back and forth over the targets, and large clouds of smoke could be seen emanating from them. Boat crews in a position to observe reported that the larger vessel disappeared in a large cloud of smoke and that only debris could be seen afterward. At 0539 Capt. McInerney ordered a Turn 9 away from the targets to guard against possible torpedoes. At 0543 a command for another Turn 9 was given. As no enemy ships were now in evidence, both vessels headed back for the survivor area.

At 0605, while rescue operations were still in progress, another enemy contact was reported bearing 178 degrees, distance 12,450 yards, course 310 degrees, speed about 24 knots. Again it proved necessary to clear survivors from alongside to engage the enemy. Both ships opened fire at 0615 at a range of 8,000 yards. The enemy returned fire, and some salvos landed near our ships. Our salvos seemed to be hitting, however, and the enemy ship became enveloped in smoke. Fire was continued until the range opened to 11,000 or 12,000 yards. In this, as in the other intermittent engagements in which the Nicholas and Radford participated during the rescue operations, the men from the Helena assisted by augmenting the personnel at the various battle stations.

Daylight was now breaking. A combination of factors prompted the Squadron Commander to order the two destroyers to retire from the area after rescuing 52 officers and 687enlisted men:12 (1) Submarines were

-------------------

12The complement of the Helena consisted of 77 officers and 1,110 enlisted men. Three officers, 34 enlisted men, and 4 marines, were wounded in action, 2 enlisted men died as a result of injuries received in action, and 7 officers and 184 enlisted men are recorded as missing.

28

likely to be in the vicinity, (2) The number and size of enemy surface units still in Kula Gulf were unknown, (3) The approach of daylight deprived us of the advantage of night fighting, (4) Enemy air attack was soon to be expected, (5) Shortly after 0340 the task group commander had advised Capt. McInerney by TBS that he would request air coverage at dawn, but this message had not been received. The four boats from the destroyers, with boat crews in the three operating boats, were left in the water near the survivors. At 1300 on 6 July, the Nicholas and Radford arrived back at Tulagi. Both they and the cruiser group which preceded them had been provided with air cover, but neither had been subjected to enemy air attack.

Comments and Conclusions

When this task group returned to Espiritu Santo the cruisers had only 30 percent usable fuel left on board while some destroyers had only 20 percent remaining. The cruisers were also very low in ammunition for their main batteries. At the time of the reversal of course at 0410, when there was some prospect that the action would be resumed, the Honolulu had only ten minutes of fire remaining for her main battery, and the St. Louis was in a similar condition.

There is some difference of opinion as to whether the enemy was taken completely by surprise when we opened fire at 0157. A period of twenty-one minutes elapsed between the time of our first radar contact with the enemy and the order to open fire. During this interval at least forty-nine TBS transmissions were made. On the other hand at no time during our approach did the enemy give any evidence that he was aware of our presence. A careful track, made over several minutes, showed him to be zigzagging in a normal manner at a speed of twenty to twenty-two knots. He did not increase his speed nor did he make any attempt to turn away until taken under fire. The task group commander has related the following incident corroborating the theory of surprise.

“The medium frequency used by the Japs was very close to the medium frequency warning net used by our own forces. We were aware of this fact, and did not use this circuit until the Helena failed to acknowledge our TBS tactical signals. When the opposing salvos were fired, and the Japanese ships burst into flames, the air was full of cries of anguish, amazement, and sheer terror in the Japanese language. These cries came in over the medium frequency warning net receiver located in CIC --

29

Flag plot and were the occasion of no little satisfaction to us. These Jap transmissions decreased as their ships were sunk or damaged and finally ceased entirely.”

The sketchy SG track and the fact that the interval opened so rapidly indicate that the second group of enemy ships may have been on a reverse course at the beginning of the engagement. Their delay in opening fire would tend to substantiate this. The maneuvering of the enemy appeared to be prompted by desperation rather than by plan or signal. As they were hit, individual ships lost speed and gave evidence of attempting to turn out of formation. When our fire opened on the second group, it turned to the right. Hits were quickly obtained on the leading ship. One of the others sheered out to the right and then continued to close the range. The remainder of the maneuvering showed no planning other than a speedy retreat or a possible effort to run aground to prevent sinking.

Just how the Helena was torpedoed is a matter for conjecture. Capt. Cecil was of the opinion that the torpedoes which found the Helena came from the last destroyer in the first enemy group, which had put on a burst of speed and closed our line. From the plot submitted by Capt. Cecil it appears that if these torpedoes had been fired at the exact moment we opened fire they would have had to be faster than any we possess in order to reach the Helena at the time she was hit. The possibility that they issued from an enemy submarine lurking in the vicinity cannot therefore be overlooked.

During the entire battle, none of our ships was hit by gunfire with the possible exception of the Helena, and she was sunk by torpedoes. In its larger aspects the action may be described as a duel between American gunfire and Japanese torpedoes. To be sure twenty-four torpedoes were fired by our destroyers independently, but no coordinated attack was attempted or ordered.

The first dispatch from the task group commander stated that a minimum of six enemy ships had been sunk and one beached. It now appears, however, that the damage inflicted on the enemy was not so extensive as first believed. In this, as in most night battles, there appears to have been some duplication in the reports of damage inflicted upon the enemy arising from the fact that several ships were firing on the same targets. Moreover it is not clear whether the Japanese ships issuing

30

from Kula Gulf during the rescue operations by the Nicholas and Radford were new arrivals or simply cripples making their escape following the earlier phases of the battle. A conservative estimate indicates that two Japanese destroyers were definitely sunk, one possibly sunk, and at least five were damaged.

NAVAL BOMBARDMENTS OF MUNDA

Bombardment of Night of 8-9 July 1943

At dawn on 9 July the 43rd Infantry Division jumped off on a 1,300 yard front along the Barike River and began advancing over a very difficult terrain. The enemy was content to fight a delaying action, making use of snipers and small raiding parties along our flanks. On the first day our advance netted us 2,500 yards and brought us in contact with the main enemy defense lines. Thenceforth our advance slowed to a few yards per hour.

At the request of the commanding general of the New Georgia Occupation Force an hour’s naval bombardment of the Munda Point area was ordered to coincide with the initial jump-off of the 43rd Division. The bombardment area was divided into four parts, and each ship was assigned s distinct sector. At 0345 a task unit of four destroyers (Farenholt (F), Buchanan, McCalla and Ralph Talbot) under the command of Capt. T. J. Ryan, Jr., entered Blanche Channel. At 0512 it commenced firing on a course of 245 degrees T. A total of 2,344 rounds of 5-inch/38 were fired by the four destroyers. At 0608, just four minutes before the scheduled completion of bombardment, a single white flare was dropped over the Farenholt followed shortly by a salvo of bombs and a strafing attack against the Ralph Talbot. No damage resulted, but it was decided to terminate the bombardment at this point and return to Tulagi.

Several cases of exhaustion among the loading crews of the Farenholt and Buchanan were reported. It is probable that the heavy demands which had been made upon the destroyers in the New Georgia operation since 29 June rather than the rate and duration of fire were mainly responsible for this.

Bombardment of 11-12 July 1943

On 11 July the 172nd Infantry disengaged and moved south in order to establish another beachhead at Laiana. The enemy quickly detected

31

this movement and infiltrated between the 169th and 172nd regiments, severing communications between the two and creating a critical situation. During the night of 11-12 July a second naval bombardment of Munda was undertaken. As originally constituted for this purpose the task group was composed of the following ships:

Montpelier and Columbia with destroyers Waller, Pringle, and Philip.

North Carolina and destroyers Stanly, Claxton, and Dyson.

Farenholt and Buchanan.

Several additional destroyers from Task Force TARE to be used as an advanced sound and radar search group.