The Navy Department Library

US Navy Capstone Strategy, Policy, Vision and Concept Documents

What to Consider Before You Write One

Peter Swartz

CQRD0020071.A1/Final

March 2009

Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of strategy and force assessments, security policy, regional analyses, and studies of political-military issues. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them.

Our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the "problem after next" as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities.

On-the-ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad.

The Strategic Studies division's charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas:

- Maritime strategy

- Future national security environment and forces

- The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf

- The full range of Asian security issues

- Insurgency and stabilization

- European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral

- West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea

- Latin America

- The world's most important navies

The Strategic Studies division is led by Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.), who is available at 703-824-2614 or mcdevitm@cna.org. The executive assistant to the director is Ms. Rathy Lewis, at 703-824-2519.

The author thanks Karin Duggan for graphic assistance; Celinda Ledford and Megan Katt for administrative assistance; and Michael McDevitt, Michael Gerson and Gerard Roncolato for their substantive contributions to completing this paper.

| Approved for distribution: | March 2009 |

| Dr. Thomas A. Bowditch Director Strategic Initiatives Group |

CNA's Quick-Response Reports (CQR) contain the best opinion of the author at the time of issue. They do not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy.

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE. DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED.

Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil

Or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123.

Copyright © 2009 CNA

|

||||||

This paper provides recommendations to appropriate US Navy offices on the drafting of US Navy "capstone" documents.

It is part of a larger study of the drafting and influence of all US Navy capstone documents since 1970.

The larger study has been published in slide format as Peter M. Swartz with Karin Duggan, U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009) (CNA MISC D0019819.A1/Final February 2009). Current plans are to update that document as required, and to publish supporting documents, in annotated briefing format, to address important facets of the data and issues it analyzes.

This paper is the first of those supporting documents. It provides a detailed set of recommendations intended to be useful to Navy decision-makers and staff officers charged with developing the current and next generations of US Navy capstone documents.

Capstone documents are those documents - typically signed by the Chief of Naval Operations - that seek to explain and guide the Navy. They have come in many guises - strategies, visions, concepts, doctrines, policies, etc. - and under many names. The larger study discusses in some detail the differences and similarities of all these types of capstone documents, as well as the context and development processes of each of them.

This paper does not address those issues in any detail, but, rather, "cuts to the chase" - focusing on recommendations of immediate use to Navy staff officers.

--1--

|

||||||

This paper - and the larger study from which it is derived - has several goals, laid out above.

All of them relate to the overarching goal of helping the Navy better articulate its overarching concepts, strategies, policies, etc. today and in the future.

The effort began with an exhaustive study of past practices - a study that forms the vast bulk of the material in U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009).

Despite the large amount of data and analysis that this study of the past has yielded, however, it was not conducted primarily to illuminate past history (although it has done so, seminally).

Rather, the data-gathering and analysis of the past was designed principally to yield useful insights for the present and future.

Thus this paper - focusing solely on those insights - is the first to be derived from the larger study, despite its basis in conclusions arrived at the very end of our data-gathering and analysis.

--2--

|

||||||

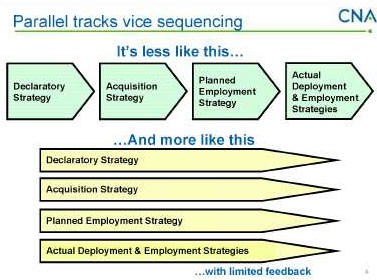

The study is about the Navy's "declaratory" strategy: What it says to itself and the world about what it should do and does, and where it is heading.

The Navy - and any the Nation's large military institutions - has many other types of strategies (and policies, visions, etc.). Ideally, they all are aligned with - and indeed derive from - its declaratory strategy.

This paper - and the larger study from which it is derived - does not purport to address in any great detail the development of these other types of strategy in anywhere near the same detail as its addressal of the Navy's declaratory strategy.

It must, however, point out to the reader the existence of these various types of strategies, and the importance of ensuring their alignment, especially if the Navy's declaratory policy is to carry any weight.

To announce, for example, that it is Navy policy to focus on power projection operations, while the Navy is in fact procuring primarily sea control capabilities, would be dysfunctional.

Likewise, to declare a Navy focus on maritime security and humanitarian assistance operations, while providing little training in those areas, would risk discrediting the capstone document in which the declaration was made - and therefore the Navy as a whole.

--3--

|

Ideally too, declaratory strategy leads and guides all the other types of strategy. War college texts and lectures are replete with exhortations to this effect, as are formal descriptions of the Navy's Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) processes.

That is not, however, what the environment actually feels like to a Navy staff officer charged with the development and promulgation of a declaratory strategy document.

That officer is more likely to be influenced - and even constrained - by the immense pressures generated by concomitant on-going fleet operations, Combatant Commander current operational and contingency plans, and Navy program and budget developments.

All of them - in his/her world - co-exist with efforts to update, change or promulgate the Navy's declaratory policy. They only sometimes appear to follow, much less derive from - his/her strategizing efforts.

--4--

|

||||||

Before beginning a discussion of what to do and how to do it, it is important to recognize the boundaries of this effort, and what this study can and cannot do.

Despite a very in-depth examination of Navy experience in developing and trying to implement past capstone documents, we were not able to derive any definitive checklist of does and don'ts that would ensure success in the future.

"Success" itself proved to be an elusive concept, with some documents purportedly designed to accomplish one set of goals, others designed to accomplish another set, and some with no announced goals at all.

Likewise, few if any of these documents came with their own processes for measuring their effectiveness, and even fewer actually had those measures implemented. Information gathered after the fact - despite an intensive effort -yielded little in the way of comparable, measurable data sets that could be rigorously analyzed, compared and contrasted, to come up with iron-clad rules that would guarantee "success" in the future.

That said, however, the data did yield a wide range of insights that will be of direct utility to current and future Navy planners, strategists and policy-makers. These insights are the subject of this paper.

--5--

|

||||||

This study is hardly the first to encounter difficulties in coming up with a clear definition of "success," or an analytically rigorous set of "measures of effectiveness, or a definitive list of does and don'ts. Leading analysts in the field have had the same experience.

The citation above from one of the leading texts on military strategy eloquently restates our premise and approach. In particular, the authors' finding regarding "questions they should ask" is significant, as it is the same finding this study had reached, prior to our examination of the cited text.

Of interest, The Making of Strategy had its origins at the Naval War College in the late 1980s, as part of the generally increased US Navy interest - and competence -in crafting capstone documents generated by the Navy's publication of successive editions of The Maritime Strategy.

--6--

|

||||||

This paper - like the larger study - is about the U.S. Navy and its capstone strategies and documents.

The Navy is not, of course, a completely independent entity. As one of the great institutions of the United States government, it is well integrated into joint, interagency, and international policies, processes, activities and operations. It is difficult if not impossible to discuss the Navy in complete isolation from its sister services, joint command and planning systems, and allied and friendly navies, and this paper does not do so. Neither does it, however, seek to give "equal time" to all of these other entities. Studies of the capstone documents of the nation, the Defense Department, the other services, and certain foreign defense agencies and services certainly do exist. Many of them were consulted in the process of conducting this study. They are not, however, the subject of this research.

Also, neither this paper nor the larger study provide the actual texts of the capstone documents that were analyzed. These have been bound together under a separate project - a collaboration between CNA and the Naval War College. The complete text of each Navy capstone document published from 1970 to 2000 (plus some explanatory remarks derived primarily from the larger CNA study) can be found in three volumes in the Naval War College Press's "Newport Papers" (NP) series, each edited by Dr. John Hattendorf: U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1970s (NP #30, 2007); U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1980s (co-edited with Peter M. Swartz) (NP #3 , 2008); and U.S. Naval Strategies in the 1990s (NP #27, 2006). Volumes containing Navy capstone documents of the 1950s and 60s, and 2001-10, are forthcoming.

--7--

|

||||||

Another feature of this paper - and of the larger study - necessary to mention is its focus on the strategic level of policy and war. Naval second-and third-echelon and theater-level operations and naval tactics are vitally important to the purpose and capabilities of the US Navy, and various official and unofficial documents address them, e.g.: Fleet Forces Command, Navy Warfare Development Command, Navy Component Commander, and Navy numbered fleet documents; and CAPT Wayne Hughes USN (Ret)'s Naval Institute Press books Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice (1986) and Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat (2nd ed.) (2000).

This study does not purport to analyze and draw conclusions on these and similar documents.

In fact, most US naval officers reading this paper and the larger study can be expected to be very tactically proficient and operationally experienced. It is the nature of service in the United States Navy. What many will not have had experience in, however, is thinking about the role of the Navy at the strategic level of war. This study is precisely designed to help fill that gap in experience.

--8--

|

||||||

The study - and this paper - have their immediate origins in the ferment within the US Navy in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century occasioned by Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (N3/N5) Vice Admiral John Morgan's drive to develop a "new maritime strategy" for the Navy.

In 2005, Admiral Morgan was developing a construct known as the "3/1 strategy," and he commissioned a number of supporting brainstorming and related efforts at CNA, the Naval War College, The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and other venues. One of those other venues was the Lockheed Martin Corporation's advanced concepts group, including Captain R. Robinson Harris, U.S. Navy (Retired). Lockheed Martin convened a workshop in 2005, and a CNA analyst was invited to make a presentation on the Navy's past experience in developing capstone documents. The presentation was very well-received, and Admiral Morgan asked CNA to continue its research and analyses in this area. Several interim studies and briefing were produced, briefed, and disseminated over the next few years, in both hard copy and electronic format. The first formal publication was U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009 )

Meanwhile, Admiral Morgan's efforts bore fruit when Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael Mullen formally tasked him in 2006 with the development of a "new maritime strategy." At the end of a very elaborate fleet-wide development process - of which the CNA efforts formed a part - A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower was signed out in 2007.

--9--

|

||||||

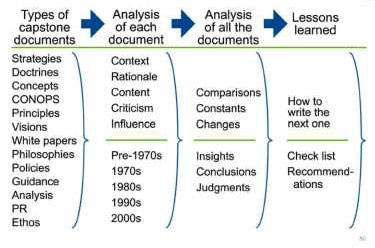

The analytic approach taken in this study was fairly basic, and conformed to normal CNA approaches and procedures.

It essentially consisted of five parts, shown above.

--10--

|

||||||

The methodology used in carrying out the approach was equally straightforward. The data-gathering effort was particularly protracted and multi-faceted, given the widely scattered location of many of the needed documentary materials, the lack of much documentary evidence, the need to declassify some documents, the requirement to continually cross-check the often-shaky but crucially important memories of participants in previous Navy capstone document development, and the necessity to present CNA's findings in a way that would be credible and useful to the Navy.

--11--

|

||||||

Having introduced this paper and its subject, and having briefly reviewed the larger study from which it is derived, we will now analyze some relevant aspects of the capstone documents published by the U.S. Navy over the past 40 or so years.

As with the rest of the paper, this section is also drawn from the larger study - U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009) - and elaborates on several of its findings.

--12--

|

||||||

As this study progressed, it became evident that very little had ever been written on this subject, and nothing in the way of a comprehensive narrative or analysis.

It also became evident that the study would not be able to identify guaranteed "keys to success" (for reasons summarized earlier, and elaborated on in U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009), MISC D0019819.A1/Final, February 2009).

Consequently, the study questions were modified as outlined above, in consultation with the study's Navy sponsor - the Director of OPNAV's Strategy and Policy Division (N5SP, later N51).

The answer to the first set of questions is the subject of this paper.

The answer to the second main question forms the bulk of the material in U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009).

--13--

|

||||

Our definition of "capstone documents" is somewhat elastic. Their fundamental features are as outlined above. They were principally identified through an extensive series of workshops, interviews and correspondence involving key Navy veterans with experience stretching back as far as the 1960s, and among whom a consensus was achieved as to which documents belong on the list.

The U.S. Navy prides itself on its "can do," ad hoc, operational and flexible mentality. It is routine for U.S. Navy officers to decry staff work and to hold in contempt doing things "by the book." This is not necessarily the case in some other U.S. services or institutions or in some foreign navies.

As a result, the Navy has never developed over the past 40 years a formal corpus of capstone documents enshrined as "doctrine," along the lines of the US Army, the U.S. joint system, or even the U.S. Marine Corps. The development of U.S. Army thinking on its purpose and its operational concepts is easily traceable, for example, through study of successive editions of appropriate and authoritative Army capstone Field Manuals, especially FM 3-0 Operations.

Not so in the U.S. Navy. The Navy had a Naval Warfare Publication (NWP) series on naval warfare in the 1950s and 1960s, signed out by a rear admiral, that was all but ignored. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James Holloway penned his own NWP on Navy strategic concepts in the 1970s. It was never updated. CNO Admiral Frank Kelso signed out a Naval Doctrine Pub (NDP) on naval warfare in 1994. It too has never been updated, as of 2009. Meanwhile, the Navy has published a steady stream of variously-styled capstone documents.

--14--

|

||||||||||||

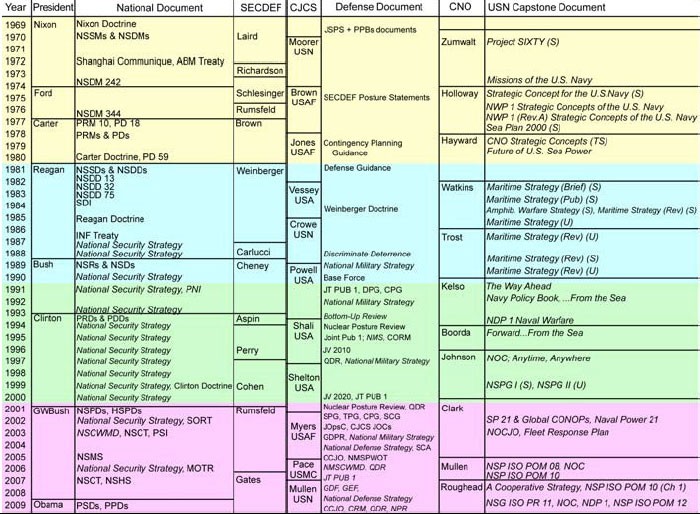

This is the list of those capstone documents, beginning with CNO Admiral Elmo Zumwalt's Project SIXTY in 1970 and concluding with Admiral Gary Roughead's 2007 A Cooperative Strategy for the 21st Century; his 2007 Navy Strategic Plan In Support Of POM 10 (Change 1); and four other documents in various stages of development as of March 2009.

All, except Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner's 1974 Missions of the Navy and the 1978 study Sea Plan 2000, were signed out by Chiefs of Naval Operations.

U.S. Marine Corps and Coast Guard officers were heavily involved in the drafting of many of these documents, notably the classified Maritime Strategy documents of the 1980s and many documents of the 1990s and 2000s. Since 1990, many have been co-signed by successive Commandants of the Marine Corps and, since 2007, by the Commandant of the Coast Guard. Some - especially in the 1990s - were co-signed by successive Secretaries of the Navy.

Some - like Project SIXTY, . .. From the Sea, and the 1997 Navy Operational Concept - sought to move the Navy in new directions. Others - like NWP1 and The Maritime Strategy - sought to codify existing Navy thinking in one coherent and compelling argument. Some were influential; others were little known.

This brief paper cannot explore the context, development history, content or influence of each of these documents in any detail. For that data and analysis -which formed the basis for the recommendations in this paper - see U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009).

--15--

|

||||||

The modern U.S. Navy - unlike the modern U.S. Army - has been fairly slipshod in its view of terminological consistency and exactitude. The Navy participates in the endless revisions to Joint Pub 1-02, the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, and has its own, recently updated, NTRP 1-02 Naval Supplement to the DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (2006). Few in the U.S. Navy consult the former, however, or even know about the existence of the latter.

Decision-makers tasking new Navy capstone documents attach whatever terms sound right to them at the time, and in keeping with their intent, as they personally understand those terms. An analyst trying to determine from a close reading of the documents themselves the difference between a "plan," a "strategy,", a "policy," a "vision" or a "concept" soon finds himself mired in a fruitless pursuit through terminological morasses. The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s and A Cooperative Strategy of the 21st Century both call themselves "strategies," but otherwise bear little resemblance to each other. Differences between the content of a Navy Operational Concept, a Naval Operating Concept and a Naval Operations Concept can defy careful scrutiny, although the terminology for the title in each case was chosen with great care and sensitivity to contemporary definitional hair-splitting, especially on the part of the joint community.

On these and other terminological issues, it would appear that U.S. Navy officer's would apply Rhett Butler's famous dictum in Gone with the Wind: "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn."

--16--

|

||||||

This listing illustrates the point.

What accounts for this terminological morass in the Navy? Why are each of these documents different? Three explanations have emerged from our analysis:

Different eras and different problems have required different kinds of documents

Different Chiefs of Naval Operations and their subordinates have felt different needs and had different goals

Different terms seem to go in and out of current fashion

The US Navy is generally indifferent to nomenclature issues, in any event

What can make this issue important is that it is difficult to determine the "success" of, say, a "strategy" or a "concept," if it is unclear - as it usually is - whether the document really is what it purports to be, and how any such "success" would be measured.

For a further discussion of the Navy's approach to terminology, in comparison to its sister services, especially as it relates to concepts, see Barry Messina, Dan Whiteneck, and Nancy Nugent, NWDC Phase 2 Study Results (CNA CAB D0017036.A1/Final, October 2007).

--17--

|

The reader will have noticed by now that the U.S. Navy has had - to be blunt - an awful lot of capstone documents. And that the trend seems to be increasing rather than decreasing.

Why is that?

Our analysis has yielded three sometimes inter-related explanations:

World conditions change

National policies & strategies change

Personalities change

The following few pages will provide more detail on each of these categories.

This is not a new phenomenon for the U.S. Navy: Edward S. Miller, in his seminal work on U.S. Navy strategic planning, War Plan Orange, documented some 27 versions of the plan over a period of 36 years, before World War II.

Nor is it a phenomenon true only of the U.S. Navy. The cartoon above is, of course, a critique of such practices in the U.S. private sector.

--18--

|

||||||

Clearly, the world has changed a great deal - and often - since 1970, when Richard M. Nixon was President of the United States and Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr. was Chief of Naval Operations. The listing above captures only some of the most salient change-triggering events that occurred over the past four decades.

Changing world conditions often necessitated changes in U.S. government and U.S. Navy thinking as to the Navy's roles and functions. The change in Egyptian allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States, the ending of the Vietnam War, the fall of close ally the Shah of Iran, and, of course, the end of the cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union all drove significant changes in U.S. Navy strategy and policy. So too did the terrorist attacks on the USS Cole, the World Trade Center, and the Pentagon within the past decade.

Thus it is not surprising that the Navy was often driven to revise its thinking, in order to continue to be relevant to the national security of the Nation.

--19--

|

||||||

Likewise - and in part reflecting the many changes in the world over the past four decades - U.S. government national security policy also changed.

The nature of the American system of government ensures two or three changes of presidential administration each decade. New administrations develop new policies, which the Navy must implement. The National Security Council system grinds out streams of formal classified and unclassified presidential national security directives (albeit changing their name with each change of administration). The annual workings of the Defense Department's planning, programming, budgeting and execution system - and its joint strategic planning system - yield an evolving series of policy documents, mostly classified, as do the biennial reviews of the joint Unified Command Plan (UCP).

Moreover, since the 1980s, and largely mandated by the U.S. Congress, a torrent of unclassified U.S. government strategy documents has been released by the White House and the Pentagon: The National Security Strategy, The National Defense Strategy, The National Military Strategy, and others. During the George W. Bush administration, these were complemented and supplemented by a host of more specialized unclassified directives, such as The National Strategy for Maritime Security and The National Strategy for Combating Terrorism.

Successive naval leaders have had to take all of these documents - and the policy changes they reflected - into account, which has often led them to revise the Navy's own capstone documents.

--20--

|

||||||

Overlaid on these changes in the world situation and national policy have been changes in personalities, especially within OPNAV, the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). Thoughtful and powerful civilian officials have come and gone, refocusing the Navy's priorities and institutions. Examples that come to mind are Secretary of Defense Harold Brown and Donald Rumsfeld, and Secretaries of the Navy John Lehman and Sean O'Keefe.

Most important has been the role of successive CNOs. Almost every CNO from Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr. on has felt a strong need to promulgate his views on what the Navy is about and where it was heading. Even the one possible exception to this rule - Admiral Jay Johnson - actually proves it: Admiral Johnson (CNO from 1996 to 2000) felt strongly that the Navy not crow about its policies and strategy publicly, shining as he felt the service was at the time under the harsh light of extremely negative press scrutiny following a blizzard of bad publicity.

CNOs are not alone in OPNAV. Not only is there an entire OPNAV staff directorate focused on strategy, plans and policy, but there are numerous special assistants who often are given policy mandates. These staff offices normally include a healthy share of thoughtful and aggressive staff officers eager to put their imprint on Navy policy and strategy. Whether or not a CNO might want a new capstone document at any point in time, there are certainly always OPNAV staff officers submitting unrequested draft documents to him anyway.

--21--

|

This complex graphic seeks to capture and summarize the phenomenon just discussed. Its complexity is not deliberate; it simply reflects the policy reality within which the Navy operates at the seat of government in Washington.

The successive Chiefs of Naval Operations listed have had to take into account all the personalities and policy documents noted - and more - in crafting their own capstone policy documents for the Navy. The result as been a steady stream of documents, reflecting the steady streams of policy influences at work on the Navy from higher authority.

Detailed data and analysis of all the influences impinging on each of the Navy's CNOs and their capstone documents is contained in U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009). Also included in that larger study are similar graphics to the one above, each focusing only on one particular decade (and easier to read).

--22--

|

| Samuel P. Huntington "National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy" US Naval Institute Proceedings (May 1954) |

Why does the Navy publish capstone documents anyway? This is a good question, and its answer was best formulated over 50 years ago by one of the past century's leading social scientists, Samuel P. Huntington. At the time a young academic at Harvard University, Dr. Huntington formulated a rationale for such documents that has stood the test of time. Extensive research in the field has yielded no better argument.

Huntington was writing only five years after the so-called "Revolt of the Admirals" in 1949. That event was a searing one for the U.S. Navy, and the culminating point of a 4-year era in which the Navy found itself often at a loss to explain its roles and functions in the post-World War II world. In a very real sense, that period was not only the basis for Huntington's thinking, but also for all U.S. Navy capstone documents ever since. (For more on the period and the Navy's search for a postwar identity, see Jeffrey Barlow, Revolt of the Admirals: The Fight for Naval Aviation (Washington DC: Naval Historical Center, 1994).

Huntington's thesis in the article was multi-faceted, and also introduced the idea of a U.S. Navy that had evolved through a progression of discrete eras since its founding in the eighteenth century. Current American naval analysts - notably Colonel Robert Work USMC (Ret) at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) have built on Huntington's construct to good effect (see especially Andrew Krepinevich and Robert Work, A New Global Defense Doctrine for the Second Transoceanic Era, CSBA 2007).

--23--

|

||||||

The passages above are at the heart of Huntington's 1954 thesis.

Huntington went on to say:

"If a service does not possess a well-defined strategic concept, the public and the political leaders will be confused as to the role of the service, uncertain as to the necessity of its existence, and apathetic or hostile to the claims made by the service upon the resource of society."

A military service capable of meeting one threat to the national security loses its reason for existence when that threat weakens or disappears. If the service is to continue to exist, it must develop a new strategic concept related to some other security threat."

He further noted that such a strategic concept had two principal audiences:

The public and the political leaders

The military service itself

It is difficult to improve on the clarity of Dr. Huntington's insight and prescription. That said, it should be noted that his article is no more consistent in its use of terminology than most Navy documents are today: "Strategic concept," "doctrine," "theory," "role," and "function" seem to be used interchangeably.

--24--

|

||||||

The views of contemporary MIT political scientist and noted defense analyst Barry Posen are also instructive. During the 2008 election year debates on the future of U.S. national security strategy, Posen postulated four functions for "grand strategy."

Applicable to "grand strategy," they also track well with reasons that have been cited for creating modern Navy capstone documents, throughout their four-decade-long history.

Dr. Posen, incidentally, is no stranger to naval policy and strategy issues, nor to U.S. Navy capstone documents: As a young academic, he had been one of the most cogent (and harshest) critics of The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s (see his "Inadvertent Nuclear War? Escalation and NATO's Northern Flank," in International Security, Fall 1982). More recently, he examined America's use of sea power in his seminal "Command of the Commons: the Military Foundations of U.S. Hegemony" (in International Security, Summer 2003).

--25--

|

||||||

Our own examination of the Navy's record in drafting more than two dozen capstone documents since 1970 has yielded three overarching rationales. They recurred repeatedly throughout the documentation we examined, the interviews with participants that we conducted, and the workshops and roundtables that we held with a wide variety of appropriate former and current naval officers and civilian naval analysts.

Navy leaders have often felt a requirement to explain why the Nation needs its Navy, as world conditions, national policies, and naval technology has changed and evolved, are promulgated.

They have also often felt required to explain just how the Navy goes about meeting the Nation's needs: Its evolving roles and functions, in the face of changing challenges and threats.

Finally, they have often wanted to lay out their vision for the Navy of the future, setting the Navy on a particular course and explaining what that course might be.

--26--

|

||||||

In varying degrees, several other rationales also surfaced during out research. In addition to those listed above, they have included:

Unify Navy elements in a common conceptual framework

Break down internal Navy community & platform parochialism

Maintain common ground with USMC and USCG

Try to influence internal Navy force structure decisions

Try to influence U.S. government policy debates & academia (sometimes)

Demonstrate USN intellectual capability and/or positive responses to change

Avoid externally imposed changes

Try to influence adversaries (sometimes)

Respond to and/or gain advantage over concepts of other services (sometimes)

--27--

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Potentially, capstone documents can "check all the boxes." They can influence a wide range of audiences, at home and abroad, including not only the Navy's governmental collaborators and allies, but also its bureaucratic rivals and planned adversaries.

Typically, however, capstone documents at best only check some of the boxes. The Navy Operational Concept (1997) aimed only to influence policies within the Navy. Others, like A Cooperative Strategy for the 21st Century (2007), sought to drive national policy as well, and to influence allies and possible adversaries.

The data on whether and how any of them has actually done this, however, is generally sparse and anecdotal. Few of the capstone documents - notably CNO Admiral Zumwalt's Project SIXTY in 1970 - included a mechanism to track the accomplishment of their goals. Few also - notably The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s - spawned a large enough body of literature at home and abroad so that their effect could be judged through analysis of those writings.

--28--

|

||||||

Within the U.S. Navy itself, the DOTMLPF construct currently in vogue throughout the Department of Defense can perform a useful function in parsing the potential impact of the Navy's capstone documents.

Capstone documents ideally inform all of these elements, ensuring consistency through the widespread distribution within the Navy of authoritative ideas and concepts.

Again, however, hard data that provides solid evidence of such impact can be hard to come by.

--29--

|

||||||

One important finding from our research and analysis is the importance that key non-U.S. Navy audiences place on the U.S. Navy's capstone documents. Operationally-focused U.S. Navy officers on the waterfront (and those at desks in the Pentagon who refuse to accept their changed circumstances) might dismiss these documents as mere "Washington"-originated "PR." They believe they possess enough knowledge as to "how the Navy really works" to ignore such formal statements of Navy goals and beliefs.

Beyond the U.S. Navy, however, are many important communities who do not possess such inside knowledge, but who crave it. Officers from the other U.S. armed services, and allied officers - especially allied naval officers - often rely inordinately on these documents to be able to discern U.S. Navy practices and intentions. This is especially true for communities - such as the U.S Army's officer corps and certain foreign Navy establishments - which have strong traditions themselves of finding utility and authoritative guidance in their own capstone documents.

These communities routinely engage in joint and combined staff talks, conferences and other venues where U.S. Navy officers often brief and discuss the latest Navy capstone document. Whatever the U.S. Navy's motives for scheduling these presentations, they are usually taken with the utmost seriousness by non-U.S. Navy participants, who often subsequently use them in formulating their own acquisition and employment policies and strategies.

--30--

|

||||||

Likewise, the Navy's capstone documents can resonate in academia. Professors at service colleges and postgraduate schools - military and civilian - use these documents to explain the U.S. Navy to their students - including the future crop of civilian defense analysts and military leaders.

The 1994 edition of the U.S. Navy's Naval Doctrine Publication 1 Naval Warfare, for example, was often unread in the wardrooms of its own service, and was never updated. Despite its being over a decade and a half out of date as of this writing, however, it is still referenced and used in war college curricula around the world as an example - indeed, as the example - of U.S. Navy thinking. What - believes the professoriat - could be more authoritative than a volume labeled Naval Doctrine Publication 1?

Defense contractors also rely on the Navy's capstone documents to discern the service's future intentions. A document like ... From the Sea (1992) or A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2007) envisions significant changes in U.S. Navy priorities, refocusing American defense industry to fulfill the Navy's perceived new needs.

Moreover, the Navy's potential opponents overseas also read these documents, running their content through their own cultural and professional filters. Some U.S. Navy capstone documents, in fact, were deliberately written with a view toward influencing adversary perceptions. Many, however, were not, although they indeed may have such influence, inadvertently and with little feedback.

--31--

|

||||||

Drafting - and subsequently defending - a U.S. Navy capstone document has seldom been easy. The Navy's record over the past four decades provides numerous examples of opposition - both internal to the Navy and external- to such efforts.

In addition to the listing of impediments above, impediments to drafting and promulgating Navy capstone documents and their substantive content include:

Joint system opposed to "service strategies"

Lack of U.S. Navy appreciation of the potential influence of these documents on others

U.S. Navy officer focus often tactical vice strategic

U.S. Navy "wariness of doctrine"

Internal U.S. Navy "turf issues

Fear of debate and discussion

Navy-Marine Corps issues

--32--

|

||||||

Most important is the inherent tension between the CNO's responsibilities to develop and defend the Navy's "program of record;" to move the Navy in new directions as that becomes necessary; and to foster the free exchange of ideas within the service that underpins success in these other two endeavors.

The CNO's responsibilities to develop a coherent and defensible program and budget submissions to the Secretary of Defense, the President and the Congress are large and clear. Most of the OPNAV staff is engaged in supporting him in these tasks. While (in an ideal world) policy, concepts and strategy would drive programs and budgets, the activities of the Pentagon focus overwhelmingly on tending - and making incremental changes to - existing force structure. OPNAV drafters of capstone documents face enormous pressures to merely follow and justify existing forces and the current budget submission to the Congress, and often to focus on those forces that are most expensive and/or most in the news.

This is not a new phenomenon. As one officer noted in a 1970 internal memo:

"Practically the entire OPNAV organization is tuned, like a tuning fork, to the vibrations of the budgetary process... There is a vast preoccupation with budgetary matters at the expense of considering planning, or readiness or requirements, or operational characteristics or any of the other elements contributing to the ability of the Fleets to fight."

--33--

|

||||||

Thus far this paper has introduced the topic at hand and provided some key facts and analyses regarding the U.S. Navy's record in drafting and promulgating its capstone documents over the past 40 years or so.

We now turn to the actual raison d'etre of this paper: "How to write one."

It bears repeating that our analysis was unable to uncover a golden list of factors that will guarantee success of a document, both because "success" itself has been variously defined - or undefined - over time; and because rigorous measures of effectiveness (MOEs) have seldom ever been applied.

What we were able to determine from our study, however, have been two important, useful and related sets of recommendations: The "right questions to ask;" and the "best practices to follow."

Drafters, promulgators and implementers of past Navy capstone documents encountered a host of problems and issues as they sought to accomplish their goals. We have studied and catalogued them all. For current and future drafters of similar documents, knowing what those issues are beforehand, and that they must be addressed, will be of great value - and will save a lot of time. Thus our discussion of the "right questions to ask."

Also, while definitive MOEs might not be available, it is clear that knowledgeable subject matter experts and analysts can make some well-informed judgments as to what actions might prove to be most productive. This paper makes those judgments.

--34--

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

To organize the treatment of the "right questions to ask," this paper uses a "checklist" format. Checklists are appropriate, familiar, and user-friendly to busy Navy staff officers and decision-makers.

Our study identified some 94 of these "right questions to ask". To make them more accessible and easy to use, we have organized them into sections.

We derived our organization scheme for the "checklist" from a short Air University thesis that sought to analyze U.S. Air Force capstone documents of the 1990s.

Other taxonomies might be possible. This one, however, has the virtues of:

Already having been applied at least once, to good effect

Illustrating that our findings are probably applicable beyond the Navy to the other U.S. armed services, and perhaps to other U.S. Government agencies, allied navies, and other foreign organizations.

--35--

|

||||||

We did not adopt Major Falkenberry's construct blindly, however.

While it appeared suitable to help organize many of the fundamental issues we identified from examining the Navy record, it omitted one of the most important issue sets: Implementation.

Thus we have added an eighth category to the major's seven.

We now turn to the details of our findings themselves. Once again, the reader is reminded that the specific data and analysis that support these findings and recommendations are contained in our larger study, from which this paper is derived: Peter M. Swartz with Karin Duggan, U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009) (CNA MISC D0019819.A1/Final February 2009).

--36--

|

||||||

The initial set of questions to be asked are in fact the most important: Why do you want to write this? It is important for decision-makers and drafters to understand what foreign, domestic and technological changes and influences have driven the decision to draft such capstone document. It is also important to understand clearly who, if anyone, outside the Navy has asked for such a document.

Study of the record of past documents shows that their rationales sometimes change as the document progresses through the drafting stage -especially if that stage is a lengthy one. The Navy's experience in drafting the Naval Operations Concept 2009 - as yet unpublished - is instructive. Drafters must remain agile throughout the drafting process to accommodate any decisions as to changed rationale. It happens.

This paper discussed earlier the different types of capstone documents that are possible - and their nomenclature. Decision-makers and drafters should be clear as to exactly what kind of document they want, and then ensure the content conforms to the intent.

The record shows examples of decision-makers tasking one thing (e.g.: a "strategy", or a "vision") and receiving something else (e.g.: a "strategic concept" or a programmatic justification.) As pointed out earlier, it also shows examples of all of these terms used interchangeably, leading to confusion on the part of many non-Navy readers who have been taught to value precision in terminology.

--37--

|

||||||

Timing is important. Decision-makers must weigh the competing virtues of getting out ahead of- and trying to drive - national policy; or following direction from higher authority already in place. Each is a legitimate and worthwhile endeavor, and each has its own plusses and minuses to consider.

This relates, of course, to the all-important previous question of "why do you want to write this document?"

Discussions of appropriate timing suffused the development process for The Future of U.S. Seapower (1979); Forward ... From the Sea (1994); and A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2006-7).

--38--

|

||||||

The Navy is a big and complex organization - in geography, resources and organization. Even highly knowledgeable decision-makers can be unaware of what has come before, and what is already "on the street".

Staff officers have a responsibility to know of - and if they do not know, to dig out - the existence of any other current existing capstone documents. Perhaps the preferred way ahead should be the updating of an earlier document, rather than publication of an entirely new document type. During the 1980s, at least eight successive versions of The Maritime Strategy were published; the power and influence of using only one title was apparent to the Navy's leaders then.

Too many current documents can lead to "document fatigue" among intended audiences, limiting their impact. In 1992 the Navy published both ... From the Sea and The Navy Policy Book; in 1994, both NDP 1 Naval Warfare and Forward. . . From the Sea, and in 1997 both a Navy Operational Concept and Anytime, Anywhere. There was occasional confusion all through that period as to which document was supposed to do what, and which one was supposed to be "Reference A."

Another vital issue to be addressed is "who is the audience?" Documents written for Sailors are - or should be - different in some respects from documents written for Navy planners and the joint community, or for the Congress. If the intended audience changes during the drafting process, then the document may have to be rewritten significantly.

--39--

|

||||||

Commitment is important. If a Navy leader wants a document to be published, and wants it to be a "success" in some way, he or she must be prepared to invest time and energy in the project, and to do so publicly. Such success as the Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2007) has enjoyed can be largely attributable to its visible identification with successive CNOs Admirals Mullen and Roughead. CNO Admiral Jay Johnson's Anytime, Anywhere (1997) and SECNAV Gordon England's Naval Power 21 (2002) had limited impact in part due to the absence of visible and sustained senior leadership support.

Not only does the CNO need to be committed to the project, but at least one other senior flag officer needs to act as a "champion" as well, in order to sustain momentum on the project. VCNO Admiral William Small performed this function for The Maritime Strategy (1981-2). OPNAV Director of Naval Warfare (OP-07) Vice Admiral Paul David Miller performed this role for The Way Ahead (1991). Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (N3/N5) Vice Admiral John Morgan played a similar role for all the Navy's capstone documents of 2006-7.

Choosing an appropriate drafter is obviously important, and here the Navy's track record has been almost uniformly excellent. The Navy normally has no problem identifying suitably educated and experienced officers to draft its capstone documents. More problematic, however, has been the issue of access. Drafters must stay in tune with champions. Whether layered down within the bureaucracy or organized as special assistants, drafter access to champions has always been a benefit, to ensure drafts accord with leadership decisions.

--40--

|

||||||

Navy capstone documents can be - and have been - drafted using normal staff procedures: Action officers write drafts, which are embellished by successive intermediate layers of the chain-of-command, in an iterative up-and-down process, until they are signed out by the CNO.

Casting a much wider net, however, is necessary to bring in outside views, surface outside-the-beltway criticisms early, identify potential allies and advocates, and prepare the groundwork for future receptivity in the Fleet and elsewhere. Efforts such as The Maritime Strategy (1980s), ... From the Sea (1992), and A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Seapower (2007) evolved elaborate mechanisms -both formal and informal - that stretched well beyond the Pentagon for input and discussion. Conferences, war games, at-sea exercises, "Comment and Discussion" letters in the Naval Institute Proceeding, etc. all have been used to good effect to enrich the development process of the Navy's capstone documents. Leaders and drafters should plan to use them whenever possible.

A pitfall to avoid is casting a wide net, creating an elaborate document development process, "letting a hundred flowers bloom," etc.... and then ignoring the inputs received. Some mechanisms - often informal - have to be instituted so that early would-be contributors - some of whom might be flag officers - do not become savage after-the fact critics, miffed that their own ideas and inputs were not incorporated in the finished work.

--41--

|

||||||

Navy capstone documents cost something. This is not often apparent - especially initially - in an OPNAV organization where staff officer drafting labor is considered a sunk cost and a free good. An officer drafting a capstone document, however, is one less officer available for other staff tasking. Endless drafting sessions and working group meetings - to solicit input and co-opt potential naysayers - can pull other officers away from other tasks.

The Navy's record shows that convening workshops and conferences involving outside-the-beltway commands and activities costs scarce travel dollars, as does commissioning contractors and Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) like CNA to support them. Extensive use of the Naval War College pulls its faculty and war gamers off other projects. To all of these extra-Pentagon entities, time is necessarily money, and must be paid for somehow.

Navy senior leaders embarking on a new capstone document should actively make adequate funding available for its development. This is especially true if the drafting is to be done under the aegis of the DCNO for Operations, Plans and Strategy (N3/N5), an official normally lacking any extensive financial resources without the personal and sustained intervention of the CNO.

Developing capstone documents often yields insights as to other needed Navy publications. Experience shows that merely tasking them in the capstone document will not necessarily result in production. Other processes must be instituted.

--42--

|

||||||

The questions above are self-explanatory. When the Navy has wished to open up the document development process, this is the range of entities it has turned to.

Secretaries of the Navy (SECNAVs) have often - but not always - been involved as participants in and signatories of Navy capstone documents. SECNAV Claytor -not CNO Admiral Holloway - signed out Sea Plan 2000 (1978). SECNAV Lehman catalyzed - but did not sign - The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s, (he did publish a companion piece on the "600-Ship Navy," alongside CNO Admiral Watkins's article on the strategy in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings "white paper " in 1986).

Marine Corps and Coast Guard headquarters staffs were actively involved in the development of The Maritime Strategy. Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) Gen Kelley signed out a companion "Amphibious Warfare Strategy" in the "white paper." During the 1990s, it became customary for Marine Corps participation to be capped by the CMC co-signing the document (with the SECNAV and the CNO).

In 2007, the precedent for including the Commandant of the Coast Guard as a cosignatory was established. This opened up new questions of bureaucratic protocol, in that there is no equivalent to the non-cabinet-ranked SECNAV in the U.S. Coast Guard's chain of command (the Commandant reports directly to the cabinet-ranked Secretary of Homeland Security).

--43--

|

||||||

The first line above is what the drafting process is all about. But there are numerous other questions to be asked regarding turning out the document.

Classification is an important issue. Documents classified at levels higher than SECRET have such stringent handling rules that their distribution - and potential influence - is limited. SECRET documents, however - and especially SECRET briefings - are the lingua franca of the American defense establishment, their classification allowing both very useful detail as well as carrying a cachet of importance. Unclassified documents can reach the widest possible audience, but can be limited as to what they can meaningfully say about potential threats and operations - the "bones" of any useful strategy document.

Documents need not be at only one classification level: Sea Plan 2000 (1978) was a SECRET study, but included a widely circulated UNCLAS "Executive Summary." CNO Admiral Hay ward's 1979 Future of U.S. Sea Power existed in both TOP SECRET and UNCLAS versions. The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s had SECRET and unclassified versions. The Navy Strategic Plan In Support of POM 08 (2006) existed in both SECRET and UNCLAS forms.

Internal inclusiveness in a document can prove vital after publication, to ensure receptivity and therefore execution. Also, if a document is intended to influence the next step in a process - like PPBE - it is helpful for it to be formatted to be easily used in that next step. The Maritime Strategy, for example, was formatted by "warfare area", making it painlessly useful to OPNAV staff officers charged with developing Navy "warfare appraisals" already parsed by warfare area.

--44--

|

||||||

We have already noted the Navy's general aversion to - indeed, often contempt for - terminological exactitude, and this issue is explored well in the early pages of U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1970-2009).

This aversion notwithstanding, however, drafters of Navy capstone documents need to consider the benefits terminological precision might bring, including better relations with the less terminologically-challenged U.S. Marine Corps, and receptivity for the document within the joint system.

The other bullets on this graphic relate to the issue of inclusiveness, touched on earlier also, with respect to Navy commands outside the Pentagon. Past documents have ranged from talking about nothing but the U.S. Navy to making special effort to discuss relationships with all sister services at length, as well as many other U.S. Government agencies and the Nation's foreign allies. Inclusiveness will increase receptivity and buy-in later on, but can dilute central themes and messages, add drag out the creation process. The point is that this is not a minor set of issues; real tradeoffs must be evaluated and decisions made.

The Marine Corps and Coast Guard in recent years have become capstone document co-signatories, which ensures their adequate coverage. Sealift - a major component of the larger U.S. Navy fleet beyond the battle force - has waxed & waned through the years as an area for discussion. The Pentagon's civilian and military leadership - often sensitive to perceived negative Navy views of jointness - routinely scrubs new Navy capstone documents for their treatment of joint commanders and sister services, with which the current Navy is inextricably linked. Not mentioning them at all ensures a cool joint reception.

--45--

|

||||||

Allies are import audiences for Navy capstone documents, intended or not, as noted earlier. Mention of their importance in the document itself can go a long way to managing allied perceptions of the United States and its Navy positively.

Threats present a more difficult and important set of issues: The Nation maintains a Navy because of them. During the 1970s and 1980s, reference to the Soviet Union as the potential adversary was routine. Even a president referred to them publicly as an "evil empire."

"Naming names" publicly is more problematic today. Who the Nation's future adversaries are is not as clear as it once was, and declaring a country as a potential adversary may well become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Yet a strategy without a threat is pretty thin gruel indeed. The solution might be to publish a SECRET strategy document, but the dangers there are that (a) it might leak and (b) a SECRET document is a poor tool for strategic communications.

Should threats be able to be explicitly named - as in a SECRET document - other issues arise, having to do with estimating enemy capabilities and intentions, and guarding against proclivities to "mirror image" enemies or attributing to them strategies that the U.S. Navy would prefer they pursue, as opposed to those they actually are pursuing. This was a major issue during the development of The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s, as discussed - carefully - in Christopher Ford and David Rosenberg's book The Admiral's Advantage: U.S. Navy Operational Intelligence in World War II and the Cold War (2005).

--46--

|

||||||

This is a series of somewhat difficult issues, each of which should be actively addressed, not ignored.

There are always a plethora of important U.S. Navy initiatives going on simultaneously. Some - indeed, many - may have the CNO's personal imprimatur. Inclusion in a capstone document may further the CNO's agenda, but if not closely linked to the original rationale of the document, may diffuse the document's message. For example, see the discussion in CDR Bryan McGrath's short article "1,000-Ship Navy and Maritime Strategy," (US Naval Institute Proceedings, January 2007), on the extent to which CNO initiatives like Global Fleet Stations and Global Maritime Partnerships should be addressed in A Cooperative Strategy for the 21st Century.

Akin to some of the issues of terminological clarity and original intent discussed earlier, it is important early on to know exactly what time frame the document is to focus on - present or future - and then focus on it. Some past documents, like The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s, dealt unabashedly with the present; while others, like The Way Ahead (1991), were clearly aimed at the future. Segueing back and forth among time frames in the same document, however, can breed confusion -and then disdain - in readers.

Finally, a word of caution on lists. They can be useful, of course (this paper, for example, has lists). But too many lists of too many types can yield reader "list fatigue" and lack of focus, a criticism often leveled at The Naval Operations Concept of 2006.

--47--

|

||||||

Prioritization is another important issue, and one often ducked by past capstone document drafters and signatories. Despite all the elements laid out in all the typologies in the Naval Operations Concept of 2006, a reader could not take away from that document a sense of what was most important. The same is true to a lesser extent of A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2007), although a certain secondary on-line and print literature has grown up that has sought to uncover priorities by tracing the document's development history. The various Navy Strategic Plans provide prioritized classified risk guidance, but these have been criticized for not being helpful enough in categories that matter. .. . From the Sea (1992) was unequivocal on the priority that it placed on power projection in the littorals, but this priority became progressively eroded in subsequent documents by the increased salience they afforded to forward presence and, later, sea control operations.

Explicitly cancelling a predecessor document has been considered impolitic, but failure to do so can lead to reader confusion as to the Navy's real agenda. Failure to ever cancel NDP1: Naval Warfare (1994) means it is still taught as authoritative in non-US Navy war colleges around the world.

Another important consideration is the central organizing framework chosen for the document. Past documents have mostly used variants of three basic models: The "VADM Stansfield Turner missions," "spectrum," and "pillars' constructs noted above. Some documents - like Sea Power 21 (2002) - have used all three. The construct adopted should reflect the original intent of the document. Our analysis in Capstone Strategies & Concepts (1970-2009), of the way past documents used each construct, should be helpful.

--48--

|

||||||

To many potential audiences - especially in Washington - a capstone document is not useful unless it says something meaningful about the Navy's programming and budgeting priorities, and especially its shipbuilding plan. Some of the "success" often attributed to The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s is said to be due to its close linkage with the Navy's "600-ship" force goal of the period. Critics have charged that A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, in seeking to avoid any such linkage, has undermined its own authority and utility.

It is important that champions and drafters of Navy capstone documents be clear on what they intend the relationship to be between the content of their document and the Navy's programmatic and budgetary goals; the reasons for that view; and how they are going to deal with the linkage (or lack of linkage) during the development process and subsequent promulgation of the document. Too distant a linkage will yield criticisms of ethereal theorizing and wishful thinking, not connected with reality; while too close a linkage to the "program of record" will elicit catcalls of the document being merely a budget justification rag.

More importantly, any seeming disconnect between the Navy's announced force goal and the concepts enunciated in the capstone document can bring cries of "A U.S. Navy in disarray." This will especially be true if current Navy force goals were published in advance of the document (a situation the Navy found itself in in 2007-9).

--49--

|

||||||

Titles can matter. The shorter, catchier, and more expressive, the more memorable - and in consequence, the more likely to be referenced. The Maritime Strategy (1980s), ... From the Sea (2002), Forward ... From the Sea (2004), and Anytime, Anywhere (2007) were short, catchy, expressive titles (although a catchy title did not save Anytime, Anywhere from almost-immediate oblivion). Project SIXTY (1970), Sea Plan 2000, Naval Power 21 (2002) and Sea Power 21 (2002) were short and catchy, but devoid of meaning. The Fleet Response Plan (2003) means something vital to Navy cognoscenti, but is opaque to anyone not wearing blue and gold. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower is almost impossible to remember or say, and its normal acronym - CS21 - is meaningless. It's power rests in its unofficial nickname, "The new maritime strategy," piggybacking (by design) on that 1980s creation.

Action items are another option to be actively considered and debated. The critical issue is whether a mechanism exists or is created to ensure that the actions tasked are actually taken. Lack of follow-through on action items calls into question the validity of the entire document. The various Naval Strategic Planning Guidance and Navy Strategic Plan documents (1999-2007) are littered with actions tasked and never completed (or even started). One possible approach is taken in ... From the Sea: Only task actions which have already been tasked beforehand, and are well on the way to completion.

Finally, there is the matter of time. If Navy leaders have not allotted enough time to develop and staff the document properly, it may well show the hallmark of hastily-completed staff work. "If you want it bad, you will get it bad."

--50--

|

||||||

Anticipating criticism and co-opting or preparing to refute it has been a characteristic of some past capstone documents. The Maritime Strategy (1980s) and A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2007) in particular were developed through an intense series of briefings and "murder boards" designed to tease out all sides of all issues and elicit efforts to deal with each. The confidence with which Navy briefers could present the resultant documents to a variety of audiences is a tribute to this aspect of their development.

Clarity of presentation is another recommended feature. The Maritime Strategy owes much to the superb editing done by US Naval Institute Proceedings editor-in-chief Fred Rainbow and his staff on Admiral Watkins's NOOK-drafted manuscript. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower was blessed with the writing skills of former CNO speechwriter CDR Bryan McGrath.

Other documents have not been so fortunate. Naval Operations Concept 2006 reads like the committee product that it is. And Sea Power 21 was scathingly critiqued in Proceedings by a respected retired U.S. Navy vice admiral for its jargon-laden content.

Admitting uncertainty in public in the face of the well-known "fog of war" is not necessarily a vice. The "Uncertainties" section of The Maritime Strategy was, in the view of many of its authors and proponents, one of that document's greatest strengths. Replicating that success should be considered.

The final bullet - all-important - is well-detailed and self-explanatory.

--51--

|

||||||

What will the document look like? Plain? Slick? Big? Small? Tucked in issues of the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings and the Marine Corps Gazette? Distributed as a stand-alone pub? Made available on the web? Kept as the responsibility of the office that drafted it or presented to the Chief of Navy Information (CHINFO) with instructions to put part or all of his organization behind it?

If it is designed for public release, is the Navy ready to brief it publicly? Are there enough appropriate and skilled Navy briefers available, and have they been well-read into the issues?

None of these are minor issues. They can - in fact - become show stoppers. Without effective dissemination and follow-through, some of the Navy's capstone documents published over the past four decades had little effect.

A picture is not necessarily worth 1000 words. The words are needed. But pictures can be useful to complement and supplement the ideas embedded in the words. Instead of mindlessly ensuring that there are a balanced number of cool pictures of submarines, aircraft, surface ships, Marines and Coastguardsmen in the publication, each picture should be carefully chosen to convey a message. The pictures in the Naval Institute Proceedings "white paper" on The Maritime Strategy (1986), for example, deliberately conveyed the message of "joint and allied." The maps in the classified internal U.S. Navy versions of The Maritime Strategy deliberately conveyed the message of "Soviet Union as target."

--52--

|

||||||

Once it's over, it's not over. Capstone document dissemination is difficult, and it must be given the same scrutiny as drafting. Briefers should be carefully chosen and groomed. Also, the briefers must include the senior Navy leadership if the document is to have any effect. When a Navy leader stands up in front of a slice of the Fleet and rattles off the concepts inherent in the latest capstone document, the Fleet pays attention. When he does not, the Fleet pays even more attention. The obvious discordant themes in the speeches of Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead at Newport in October 2007 conveyed clearly that, while the CNO was foursquare behind A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, the waning Bush administration might not be.

On the other hand, The Navy Policy Book (1992), while clearly CNO Admiral Frank Kelso's brainchild, seldom received attention in the speeches or articles of other flag officers. With the CNO alone as its champion, and ... From the Sea issued almost simultaneously, The Navy Policy Book gained little traction.

Support from the fleet is important. Many of the earlier questions in this paper addressed the need to involve the Fleet during the document's development. If that has been done well, then Fleet buy-in will be easier. Such buy-in is best achieved through operations, not words: Exercises, war-games, real-world operations and training sessions that make real the words of the document.

--53--

|

||||||

In a Navy where key strategy and policy staff officers at the Washington level normally turn over every one or two years, momentum gained by document champions and drafters must be sustained through their reliefs to ensure any capstone document's lasting effect. Before they became CNO, Admirals James Watkins, Carl Trost, and Frank Kelso were all involved in the drafting of successive versions of The Maritime Strategy. Their approval had been sought and obtained. Thus, as each succeeded Admiral Thomas Hay ward, continuity of support and approach was ensured at the highest levels of the Navy, and the message of continuity trickled down to their subordinates. By contrast, when Admiral Frank Kelso retired as CNO in 1994, no one took his place as a champion of his Total Quality Leadership (TQL) program and its artifact, The Navy Policy Book (1992). The demise of both occurred rapidly thereafter.

Champions and drafters should consider actively grooming cadres of successors if they want their efforts to last.

One possible way in which this can be done is through Pass-Down-The-Line logs of some type - or formal histories - that lay out what had gone before and that challenge the new team to continue the momentum. This was yet another aspect of the experience of the drafters of The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s.

One last point: If impassioned debate had been a hallmark of the document development process, it may not be easy cut it off following formal publication. Leaders should consider how to continue - and channel - this energy.

--54--

|

||||||

Curiously, engagement of the Chief of Navy Information (CHINFO) and his organization in the distribution process has not often occurred in the history of the Navy's experience with capstone documents over the past four decades. This has normally been the result of line officer ignorance and neglect, not malice, and there have been some great exceptions: CHINFO production of a video on The Maritime Strategy in 1987, and the current CHINFO media blitz regarding A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower. CHINFO officers will not be able to play (or even know what is going on), however, if champions and drafters do not engage them early on in the development process.

On the other hand, the dissemination process cannot be left completely in the hands of CHINFO. It is the Navy community of strategy specialists, headed by the DCNO for Operations, Plans and Strategy (OPNAV N3/N5), which is charged by the Navy with maintaining links with the larger defense strategy and policy community, including think tanks, academia, private authors, and key members of the retired Navy policy community. Other OPNAV subspecialty sponsors track similar networks. All need to be engaged to 'get the word out."

Both subspecialty sponsors and CHINFO need to remain sensitive to the emergence of new media. Then-Strategy Branch Head (now OPNAV N513) Captain Thomas Daly and Public Affairs Officer (PAO) Captain Kendall Pease succeeded in launching the afore-mentioned video - the necessity for which had eluded their predecessors. OPNAV N3/N5 Cooperative Strategy drafter Commander Bryan McGrath and PAO Commander Cappy Surette pushed the newly- emerging blogs as a communications medium in 2008.

--55--

|

||||||

It still isn't over.

Decisions pile on decisions in the distribution phase of capstone document promulgation.

Developing an appropriate game plan that takes account of all of the above potential audiences should be a shared responsibility between the office creating the document - normally but not always in OPNAV N3/N5 - and the organization of the Chief of Navy Information (CHINFO).

The Navy's Office of Legislative affairs (OLA) must also be consulted regarding presenting the document to members of Congress and their staffs.

The earlier and deeper this engagement takes place between the responsible Navy drafting organization and CHINFO, OLA, and other offices, the more effective the final distribution of the document will be.

--56--

|

||||||

Unlike most of the preceding, this section is not based on a deep mining of a prodigious data set collected for this study. Such data regarding "measuring" simply doesn 't exist. Typically, once a document was published, nobody in the Navy systematically kept track of how well it was doing, or what that even meant. A few anecdotal kudos suitable for officer fitness reports, and some articles and letters in the Naval Institute Proceedings - often by critics - are normally the only such data available.

There are a few exceptions:

CNO Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr. set up an institution within OPNAV under Captain Emmett Tidd as Decision coordinator in 1970, in part to track the success of his initiatives in Project SIXTY during his term of office.

An annotated record was kept of all writings - pro or con - on The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s (that data is now at Appendix II of Dr. John B. Hattendorf's Newport Paper #19, The Evolution of the U.S. Navy's Maritime Strategy, 1977-1986 (2004). No formal analysis has ever been conducted of this data, however, other than that appearing in U.S. Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1970-2009).

There is a current (2009), ongoing CNO Admiral Roughead-initiated program of OPNAV VTC dialogues with the Navy Component Commanders in the field, on implementation of initiatives relating to A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower.

--57--

|

||||||

This is the section that Major Falkenberry overlooked in her otherwise very useful analysis of U.S. Air Force capstone documents of the 1990s.

It should not, however, be overlooked by champions and drafters of U.S. Navy capstone documents (or U.S. Air Force documents, for that matter).

Implementation is everything. Otherwise, why bother to draft a document?

And pursuing implementation should not start only when the document has been completed, as has so often been the case. Champions should be planning and starting to put implementation initiatives in place well before the ink is dry on the documents. Otherwise, valuable time and momentum can be lost, and the document become yet another "shelf puppy."

For example, it is not enough for a capstone document to tout a particular type of operation for that operation to achieve salience on the waterfront and at sea. The Fleet must feel the requirement from one or more joint Combatant Commanders and Navy Component commanders. Curricula have to be developed to train people in the operation; exercises developed to test entire units in the operation; and money allocated for any new equipment needed to carry out the operation.

All of these initiatives take long periods of time, and typically encounter numerous roadblocks and delays, from current operational priorities as well as from competing new Navy initiatives. Yet delay in implementing them can cause the Fleet to believe that the new document's injunctions are hollow, since they are not backed up by any visible actions. Ideally, implementation at sea begins the day the document is published.

--58--

|

||||||

Implementation cannot be ensured simply by publishing a document.

Publication of CNO Admiral Zumwalt's Project SIXTY (1970) hardly resulted in achieving all the programs he outlined therein. Naval War College President Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner's careful descriptions of "sea control" and "power projection" in Missions of the U.S. Navy (1974) were not followed by his successors, although his terms themselves achieved wide currency. On the other hand, despite his best efforts and his personal drafting of NWP 1 Strategic Concepts of the U.S. Navy (1975-8), CNO Admiral James Holloway was unable to supplant Turner's by-then well established "four missions of the Navy construct" with his own modification. Proclamation of the virtues of new Naval Expeditionary Forces in ... Forward from the Sea (1992) and NDP 1 Naval Warfare (1994) did not result in their becoming part of fleet organization.

Active monitoring and goading of implementation from the top is required if it is to succeed. If not, the record shows high potential for the document becoming irrelevant.

Also, imaginative as it may be for capstone documents to offer alternatives, identify deficiencies, and highlight uncertainties, these assessments are of little consequence if they are not followed up by examinations of their implications in analyses, war games, exercises and the development of new concepts.

The last bullet is a question that recurs frequently. It restarts the cycle.

--59--

|

||||||