The Navy Department Library

COMBAT NARRATIVES

The Assault on Kwajalein and Majuro (Part One)

Office of Naval Intelligence

U. S. Navy

PDF Version [36.5MB]

COMBAT NARRATIVES

The Assault on Kwajalein and Majuro

(Part One)

PUBLICATIONS BRANCH

OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE * UNITED STATES NAVY

1945

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D. C.

1 March 1945.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U. S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

{SIGNATURE}

HEWLETT THEBAUD,

REAR ADMIRAL, U. S. N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence

II

CONFIDENTIAL

Foreword

1 March 1945.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publication Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

{SIGNATURE}

E. J. KING

FLEET ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

CONFIDENTIAL

III

Charts and Illustrations

| Facing Page | |

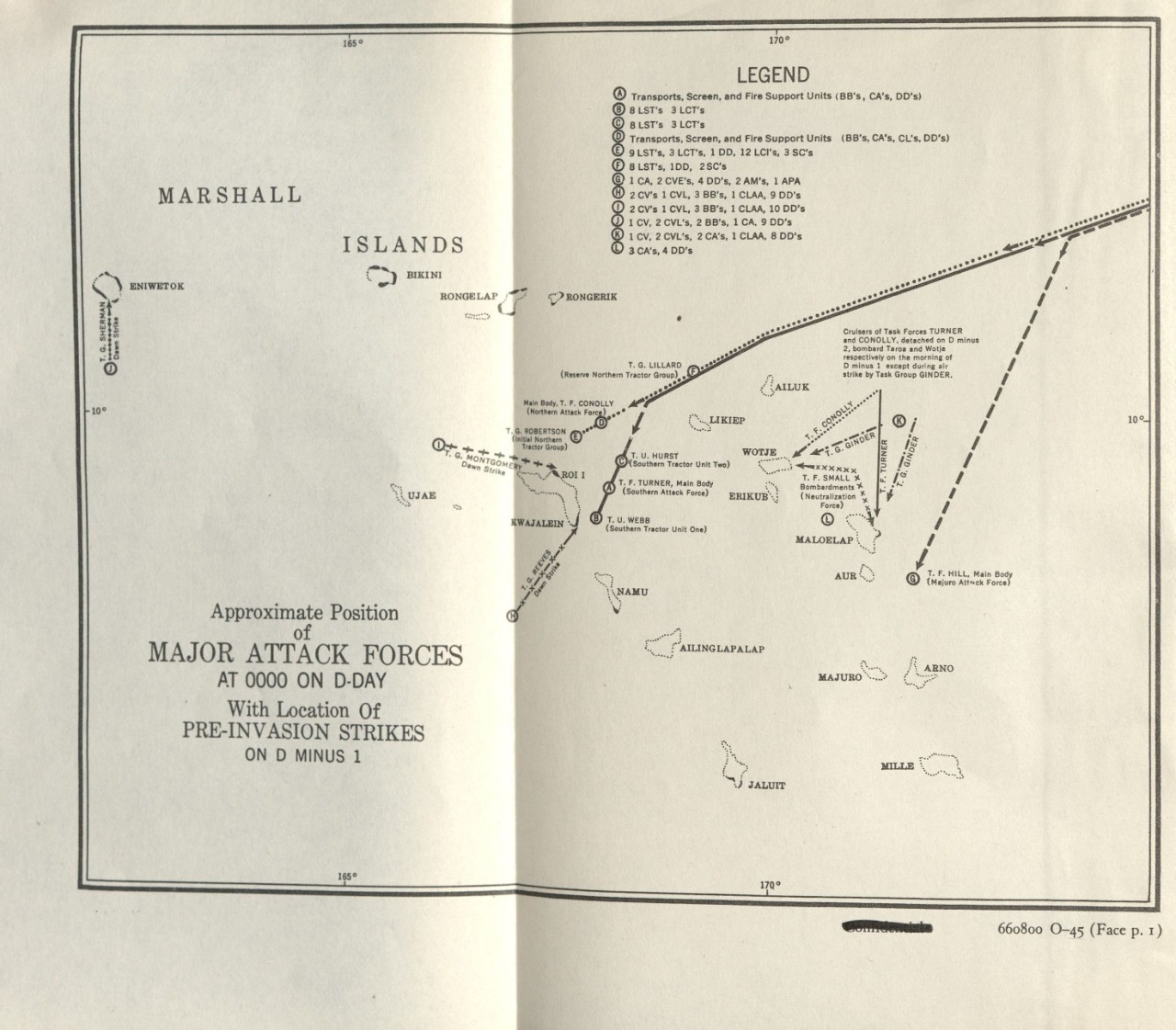

| Chart: Major Attack Forces D-Day | 1 |

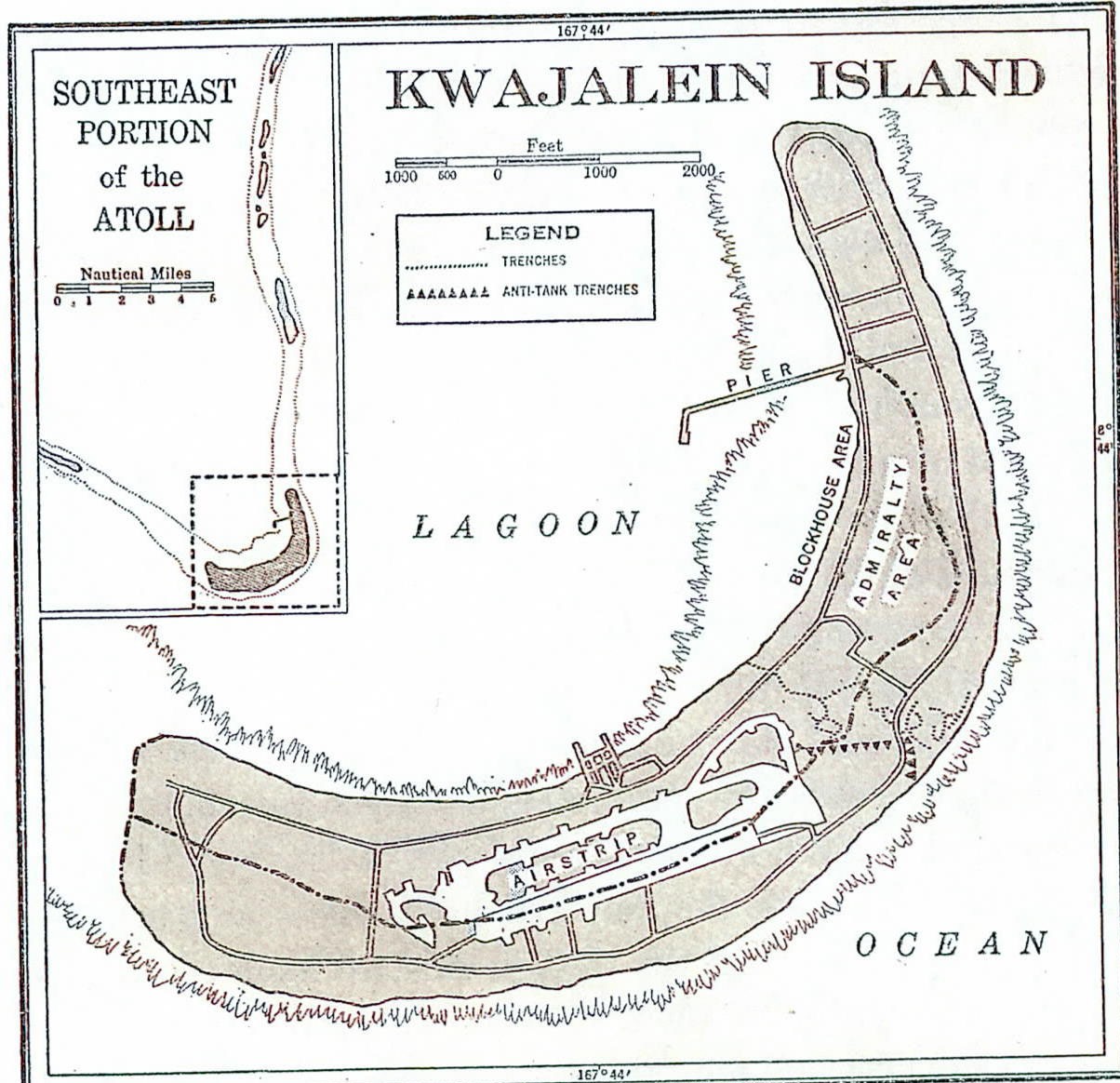

| Chart: Kwajalein Island | on page 4 |

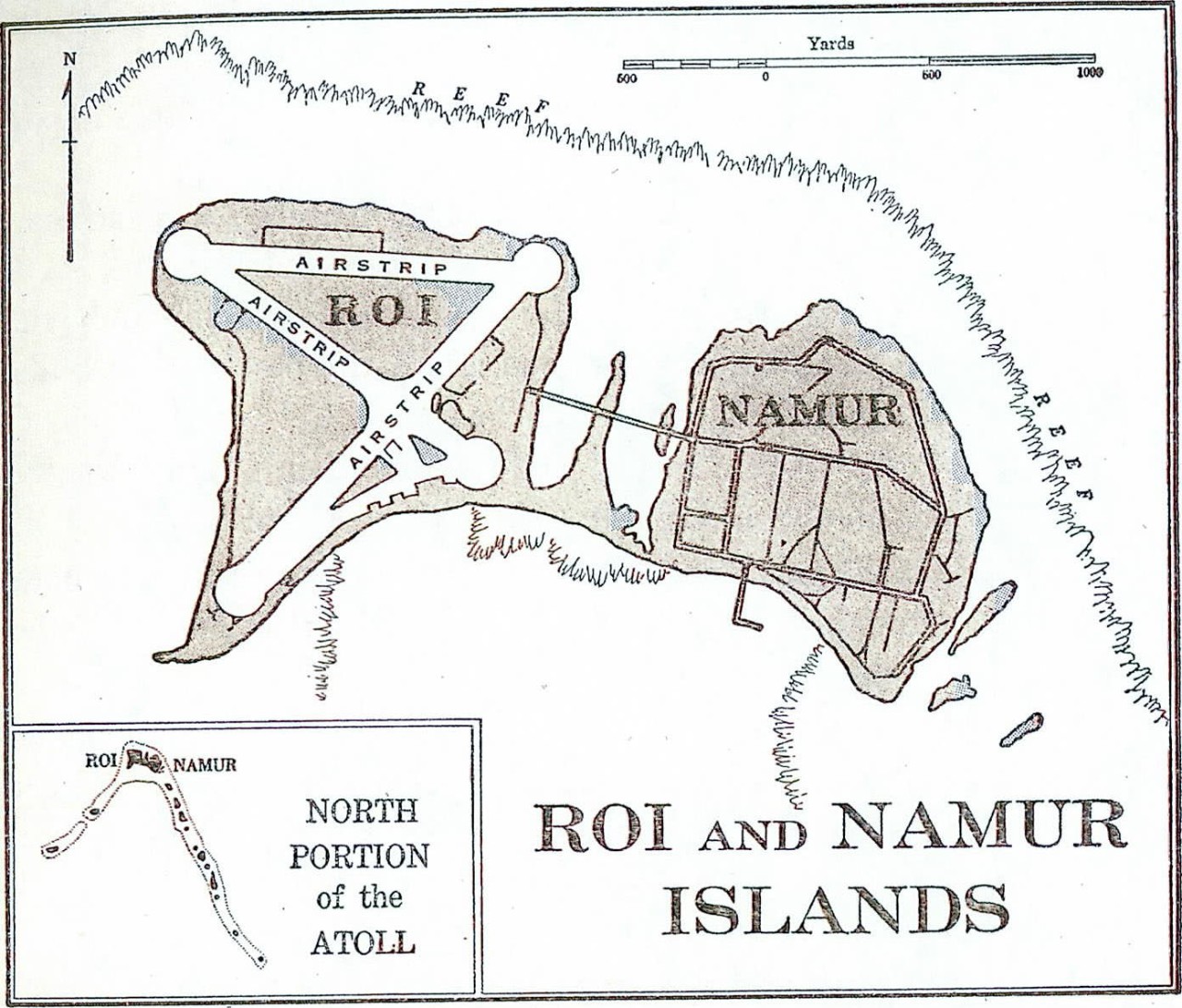

| Chart: Roi and Namur | on page 5 |

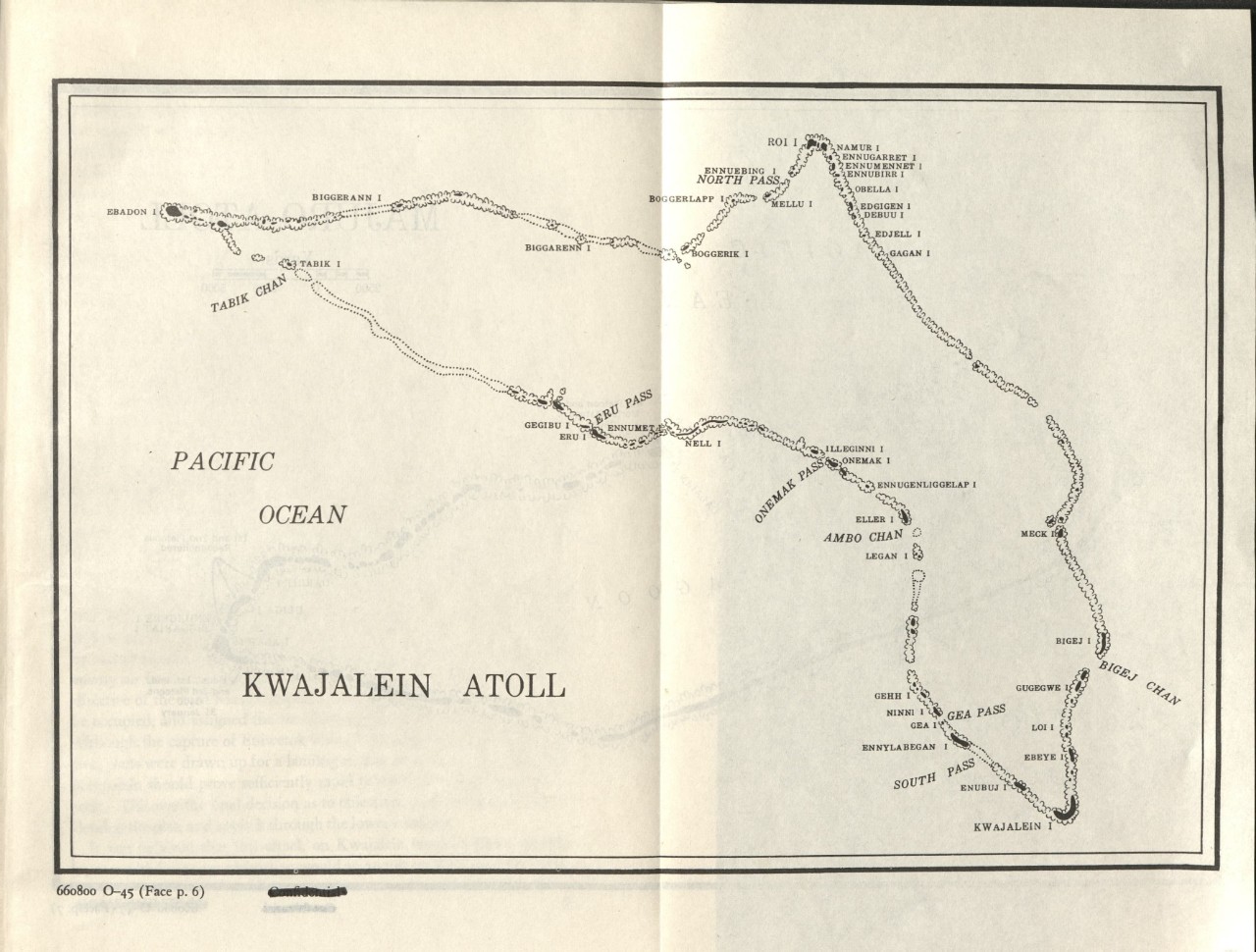

| Chart: Kwajalein Atoll | 6 |

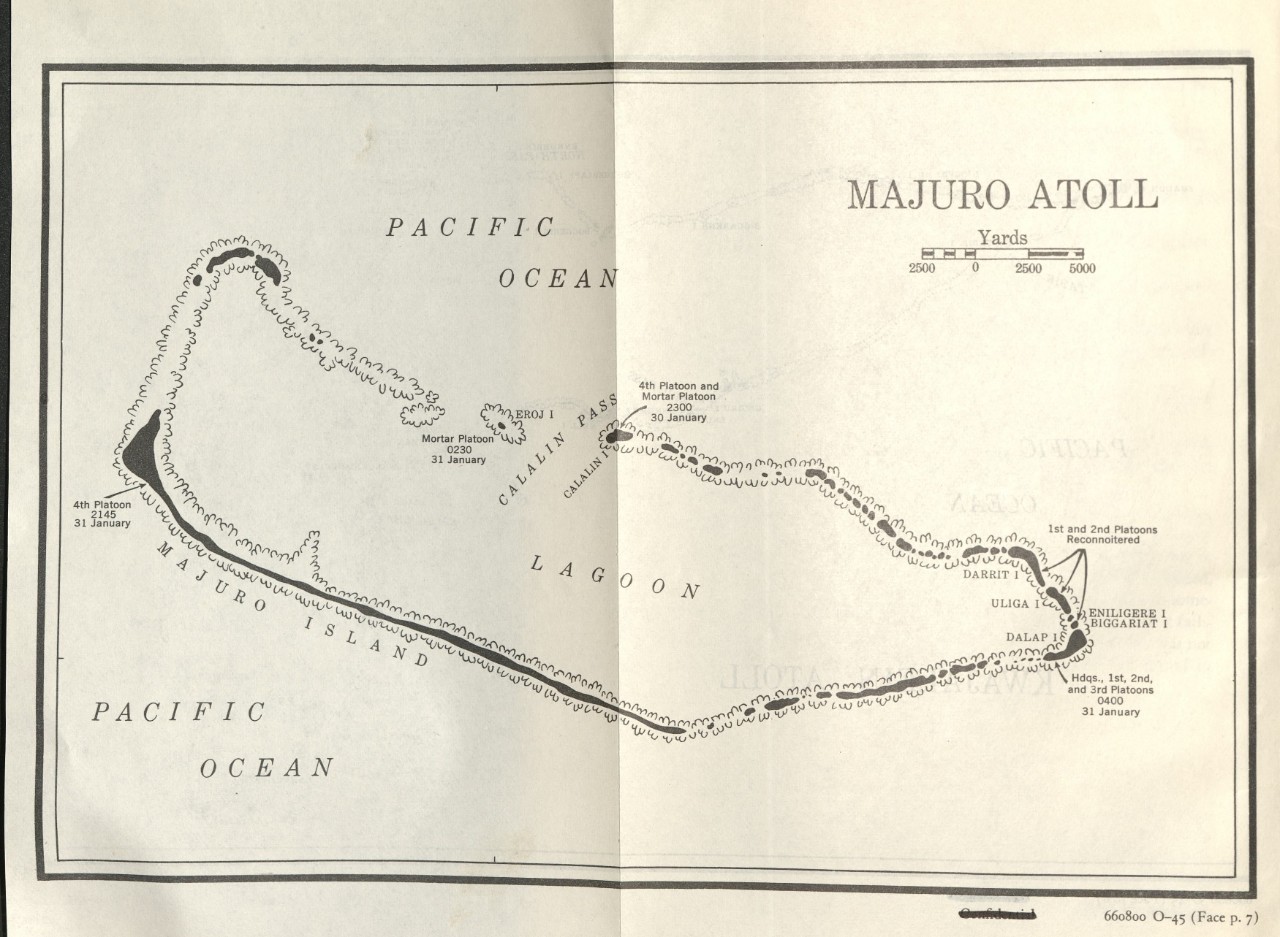

| Chart: Majuro Atoll | 7 |

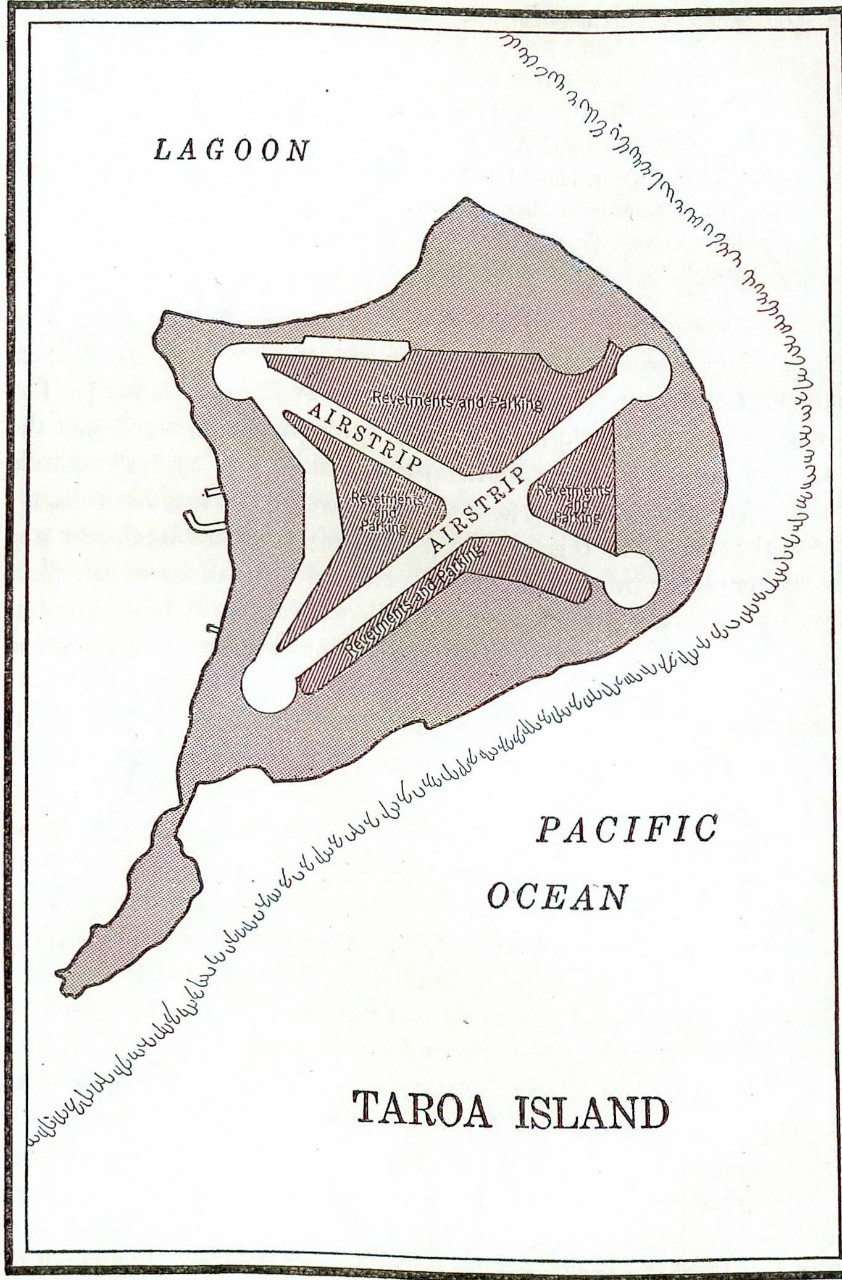

| Chart: Taroa Island | on page 24 |

| Illustrations | between pages 26-27 |

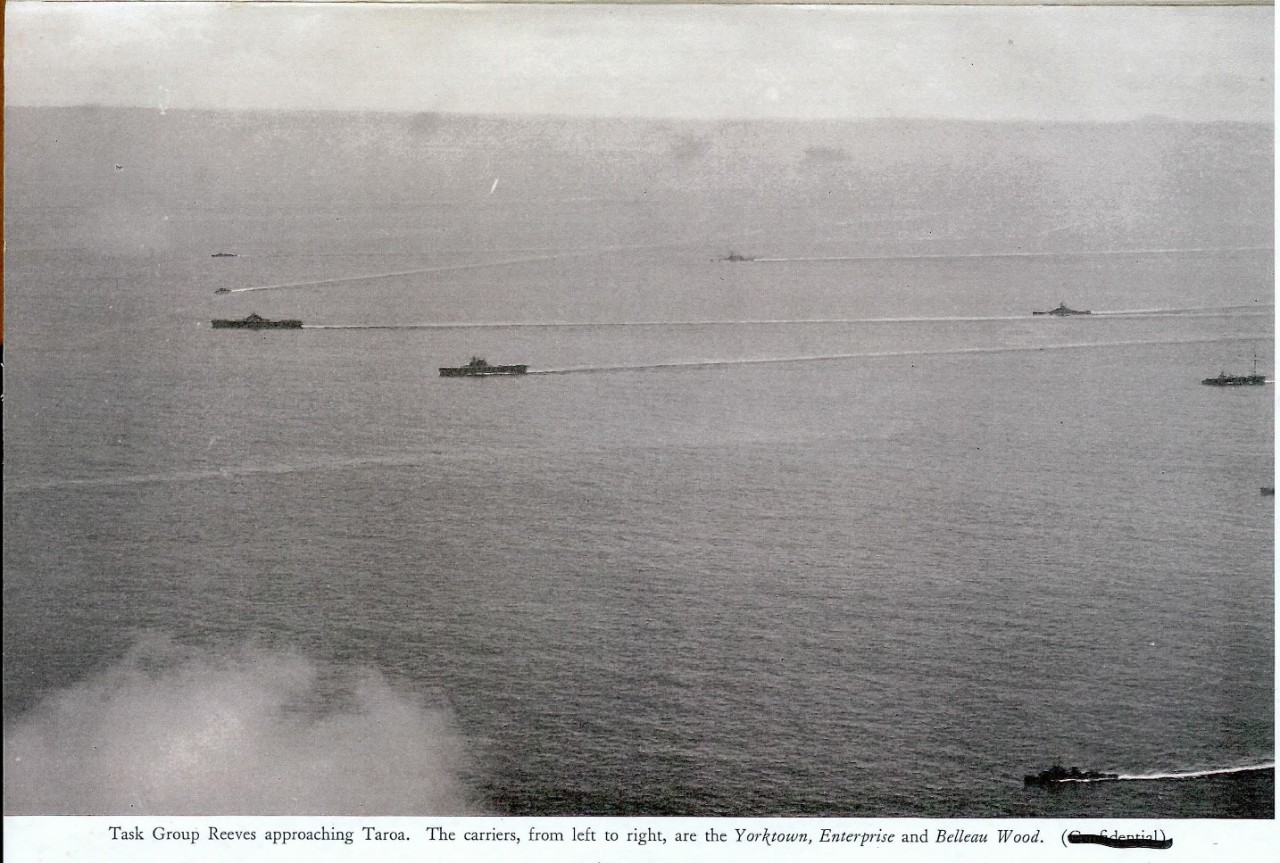

| Task Group Reeves approaching Taroa | |

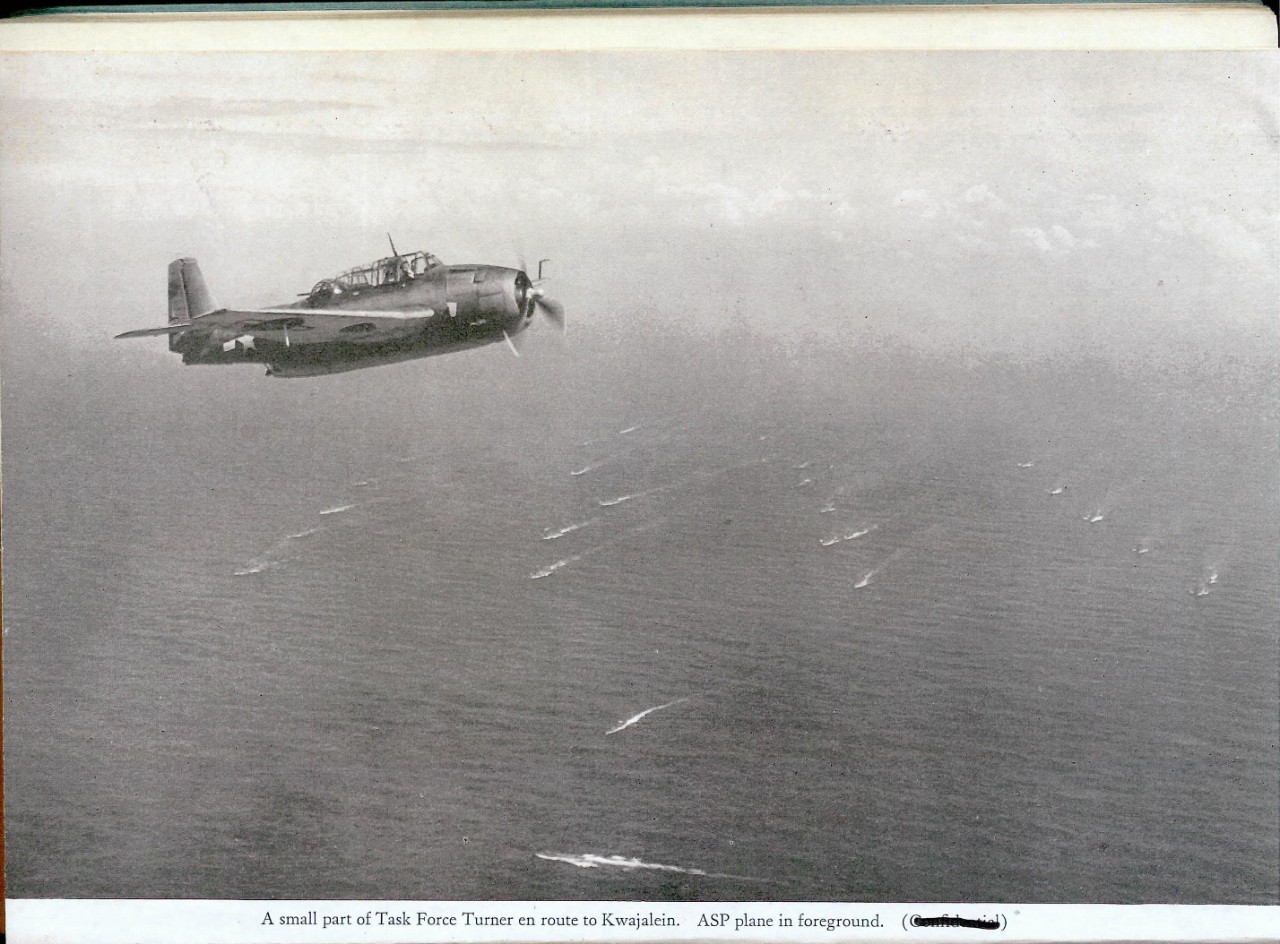

| A small part of Task Force Turner | |

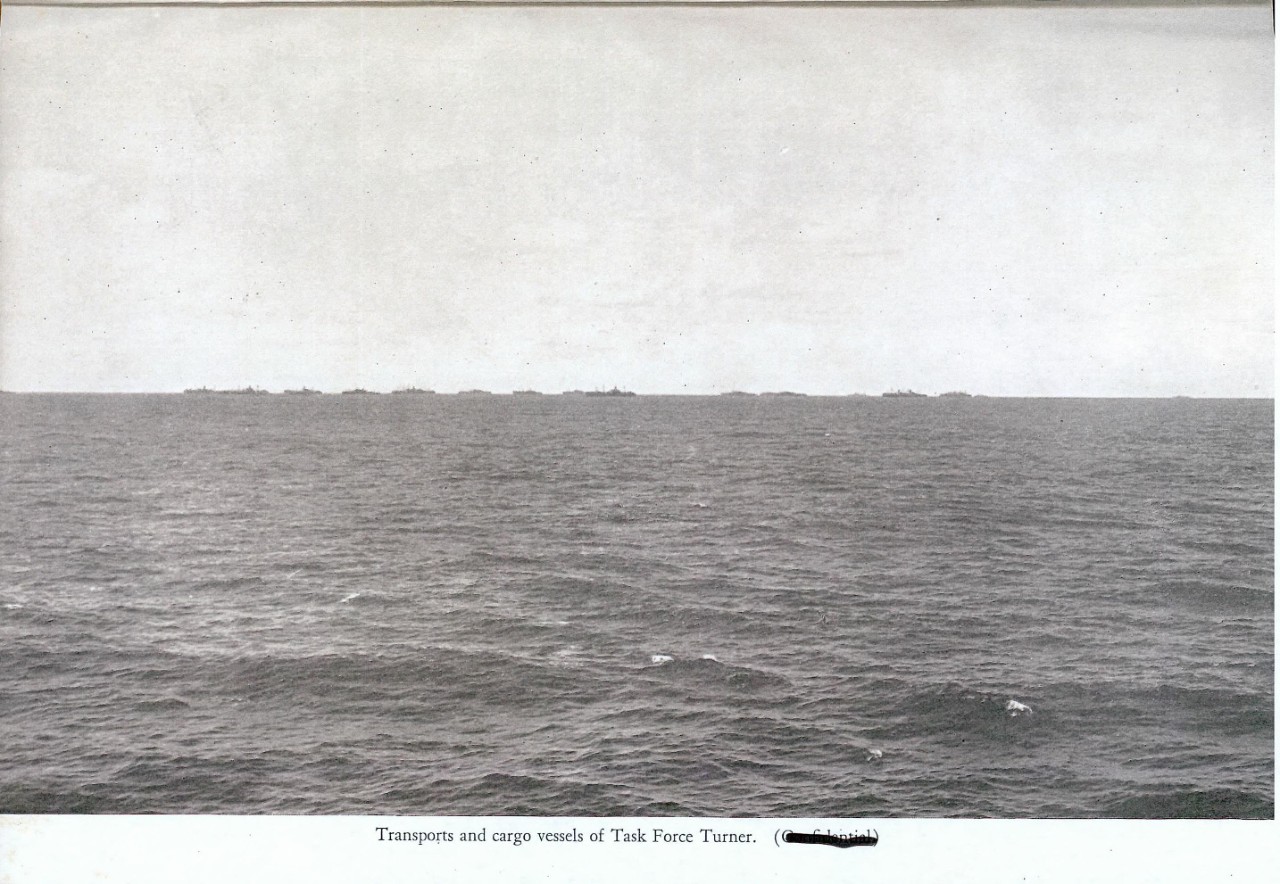

| Transports and cargo vessels of Task Force Turner | |

| TBF's returning to the Enterprise | |

| Illustrations | between pages 42-43 |

| Roi under attack | |

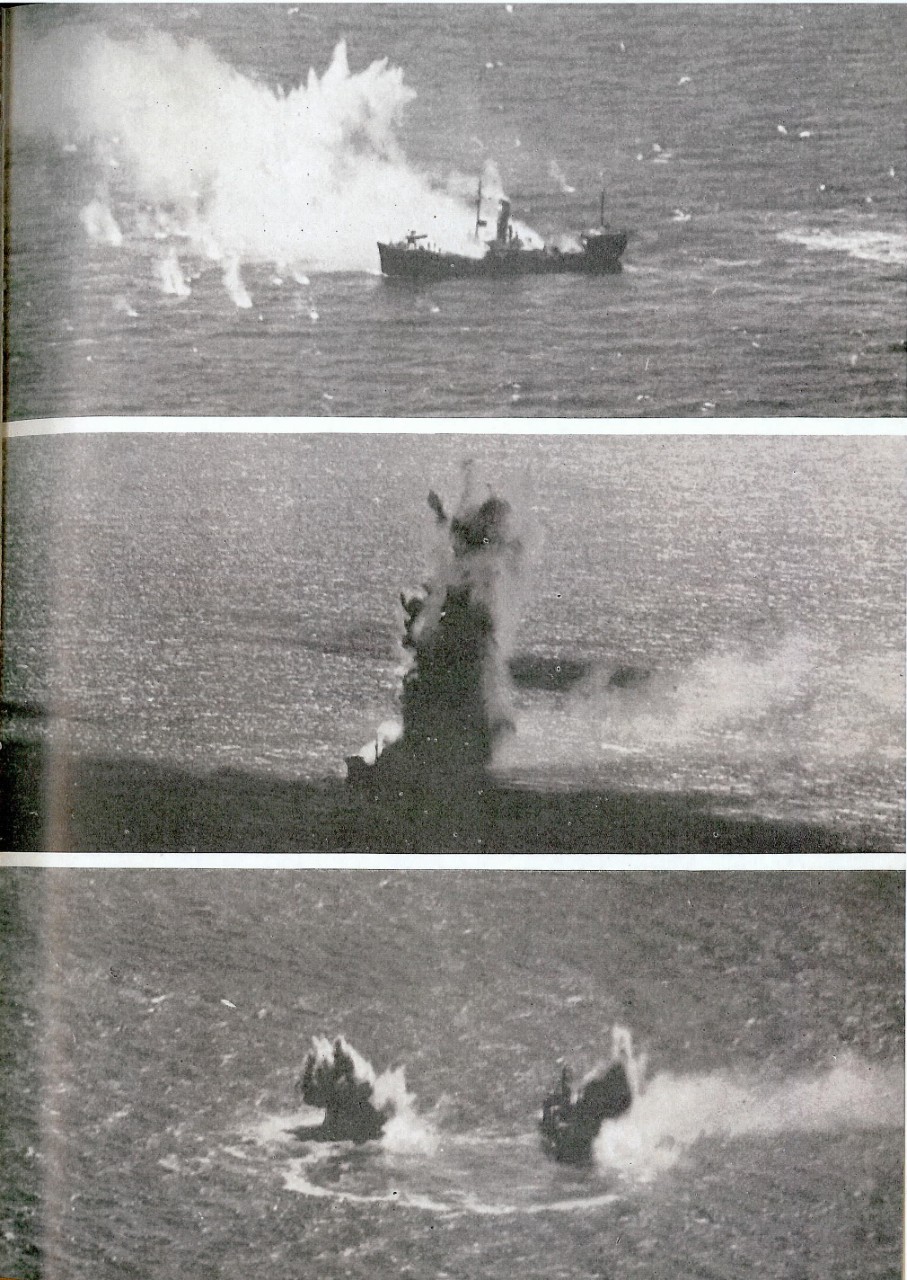

| Attack on Japanese net layer | |

| Enterprise TBF's attacking Taroa | |

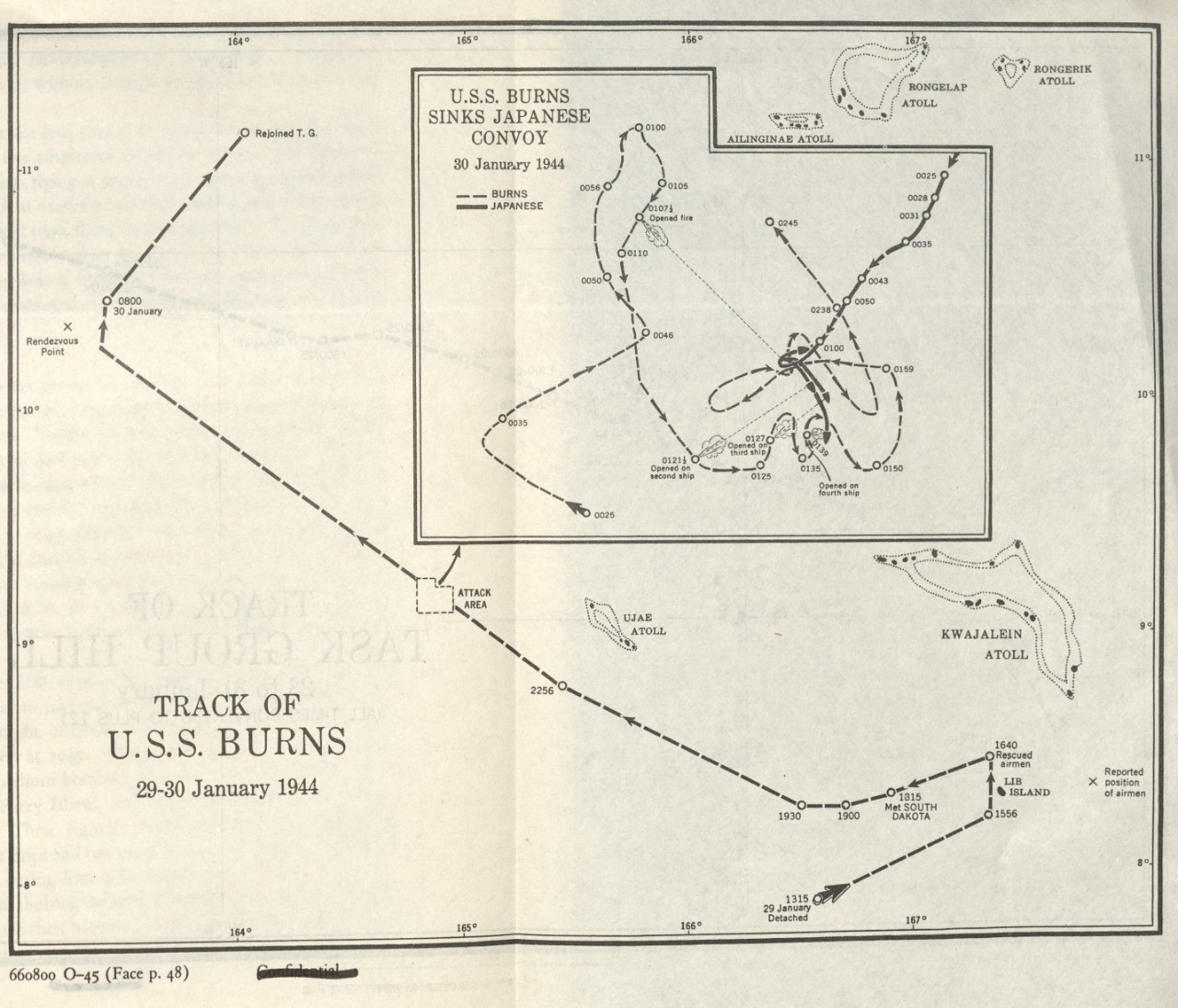

| Chart: Track of the Burns | 48 |

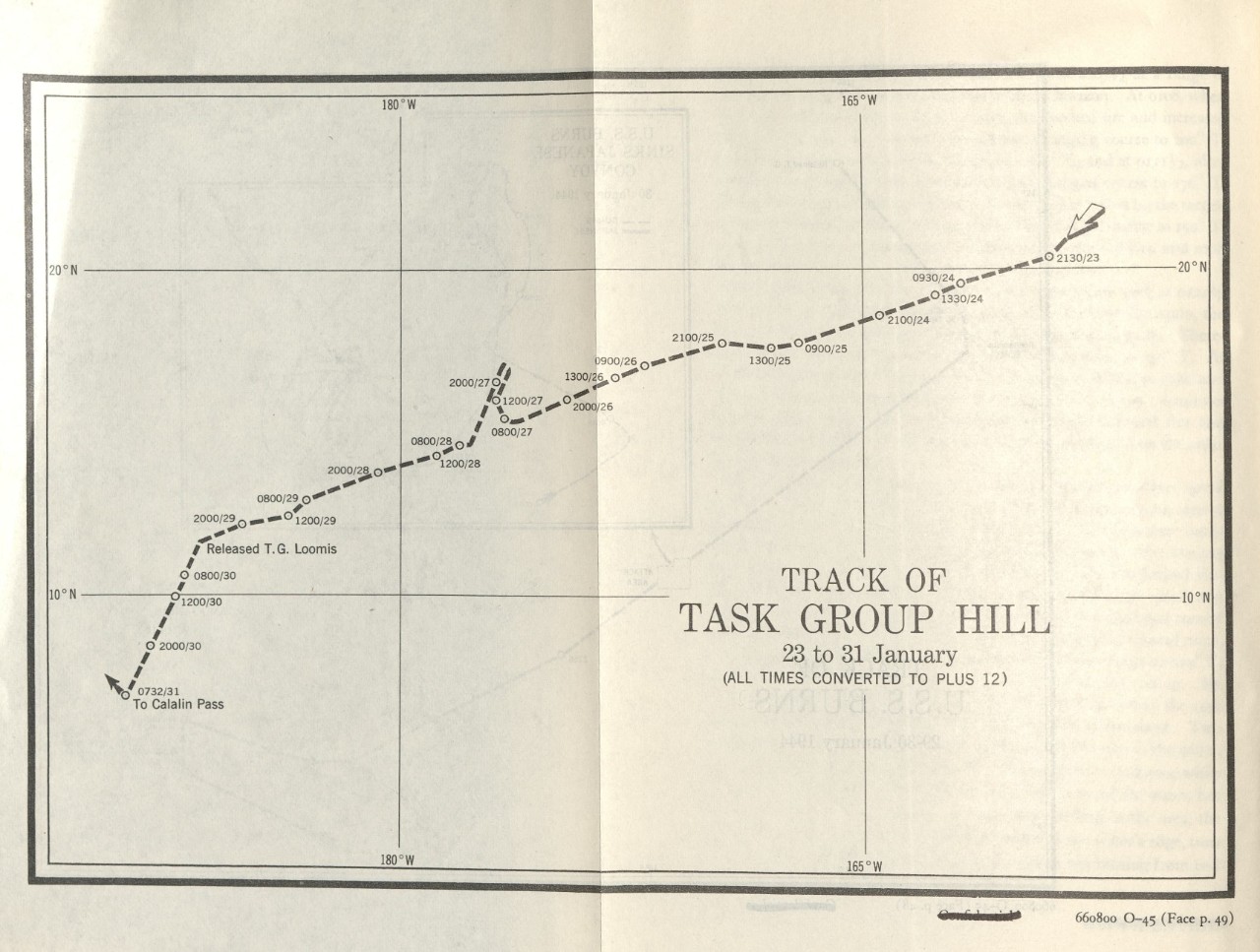

| Chart: Track of Task Group Hill | 49 |

| Illustrations | between pages 58-59 |

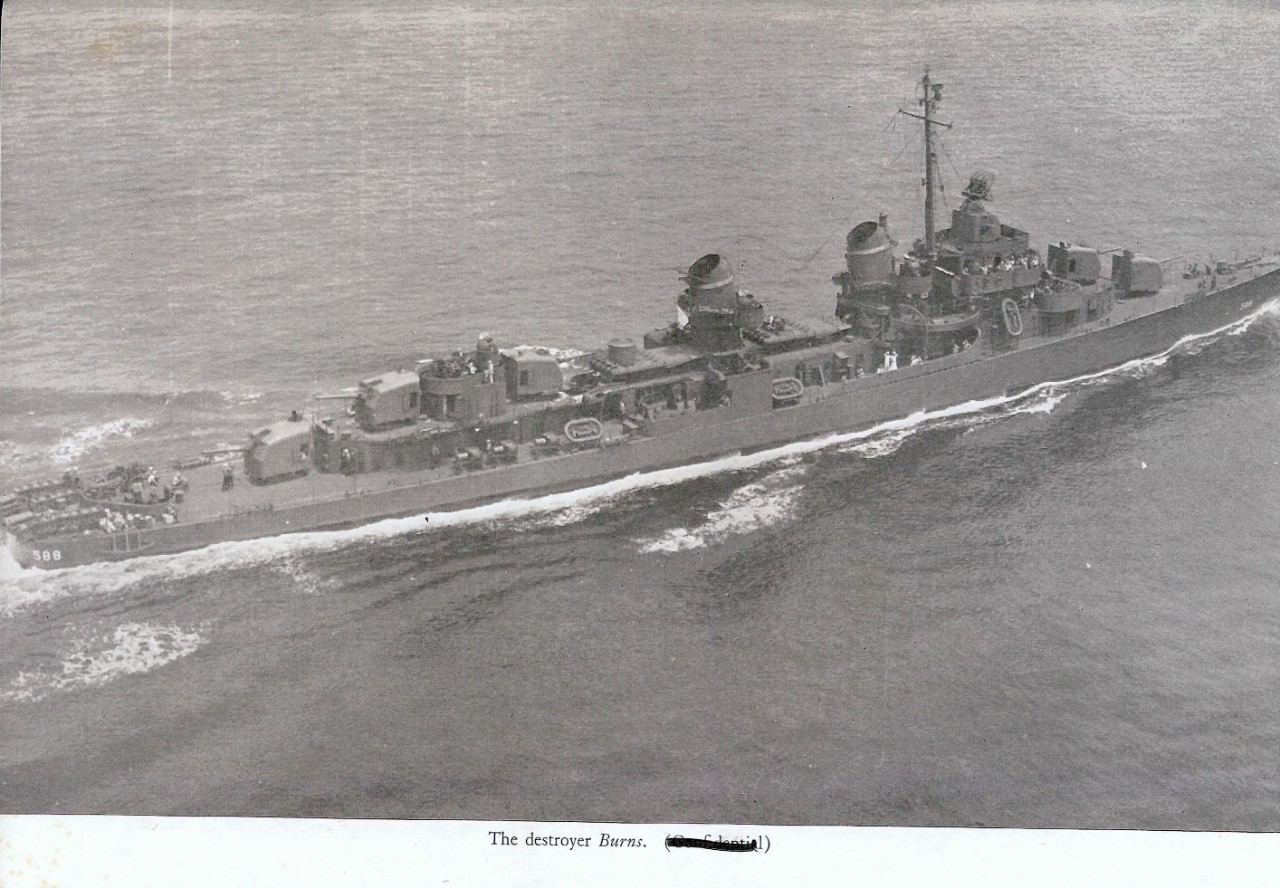

| The destroyer Burns | |

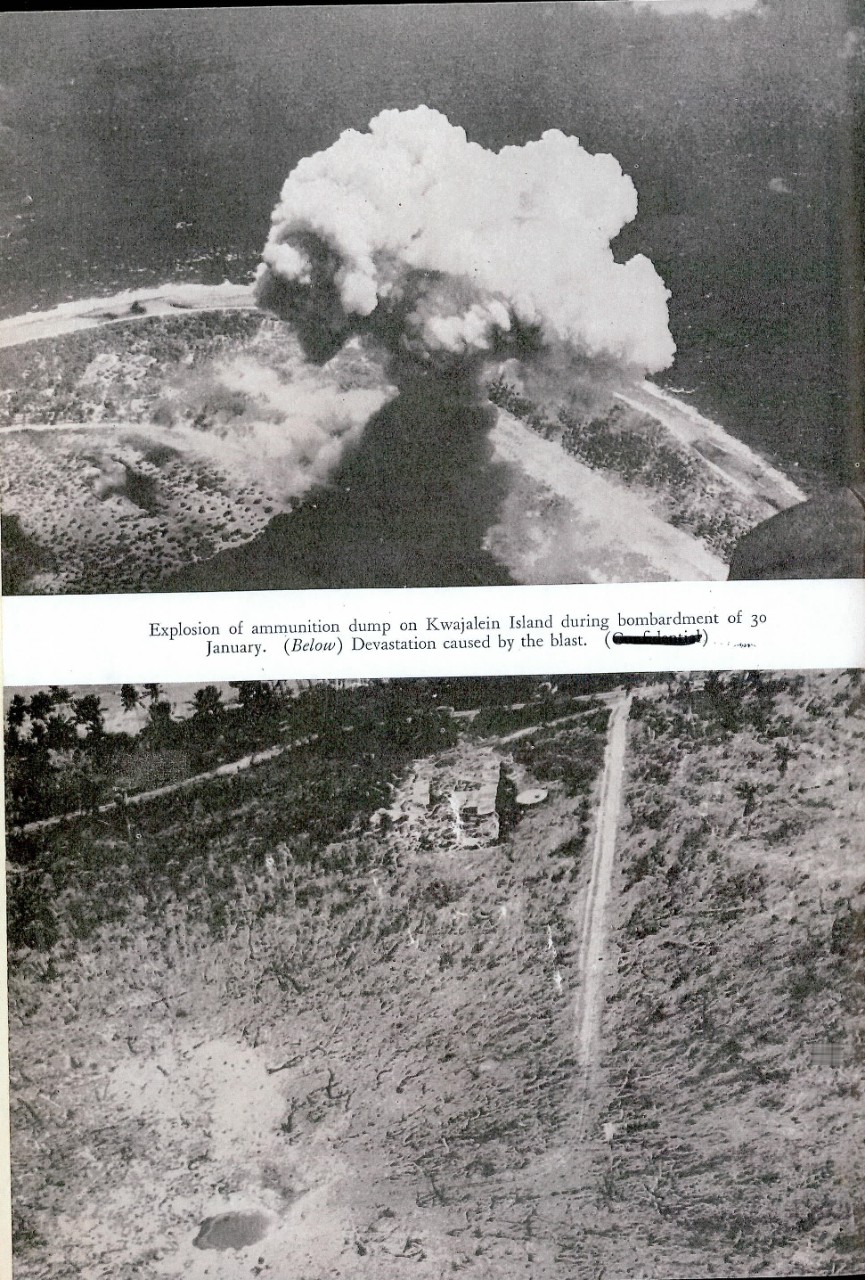

| Explosion on Kwajalein | |

| Devastation caused by the blast | |

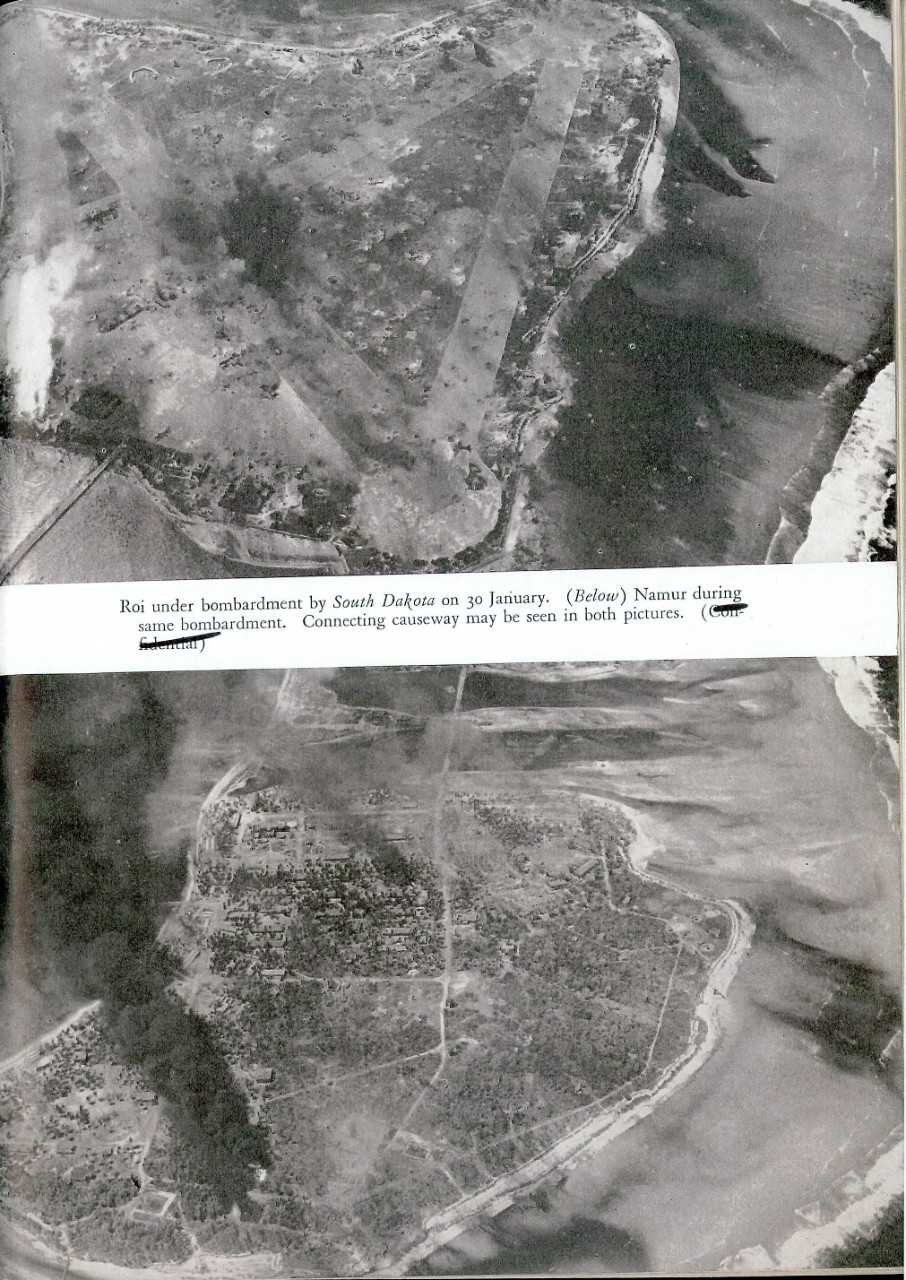

| Roi under attack by South Dakota | |

| Namur under attack by South Dakota | |

| Namur on 30 January | |

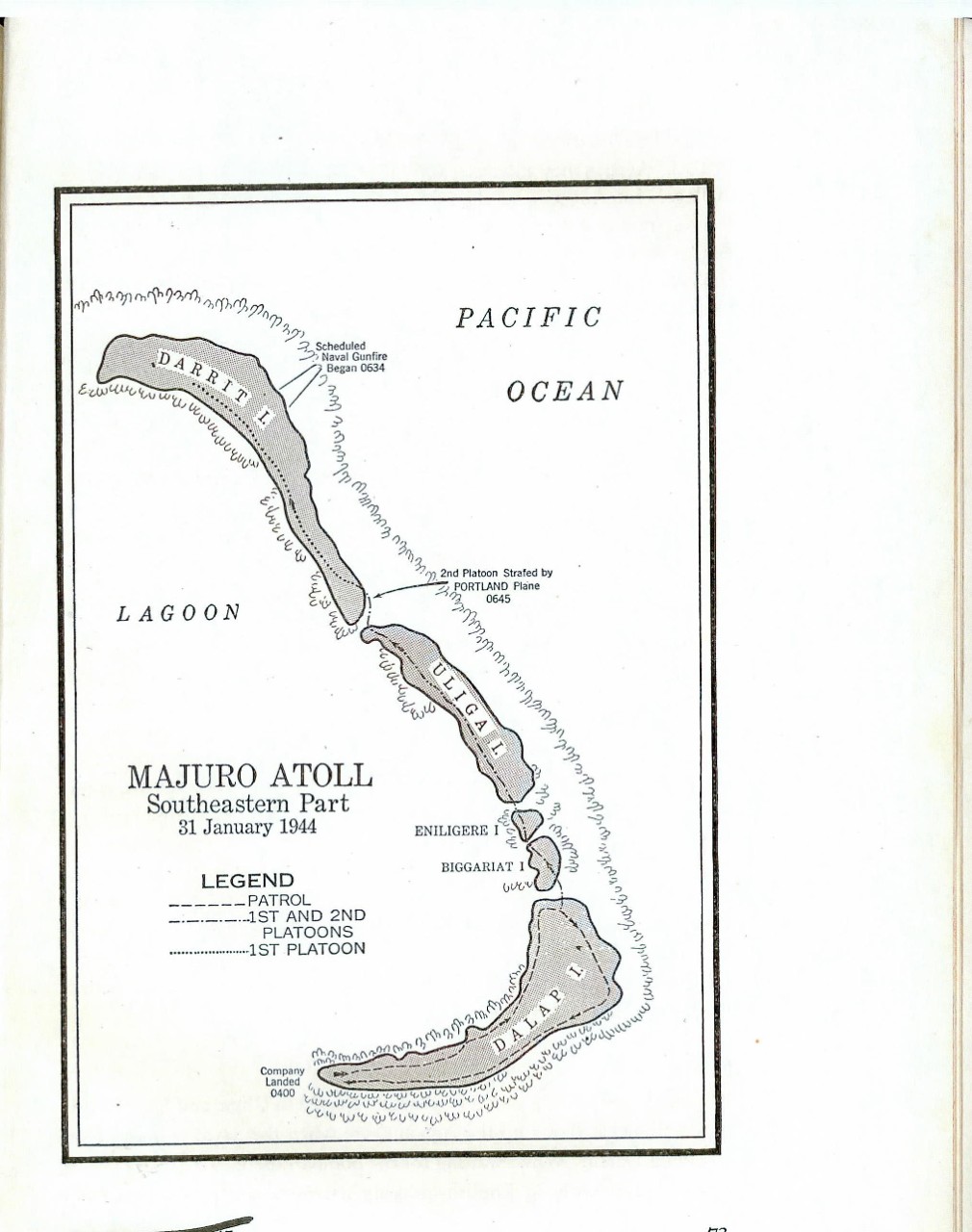

| Chart: Majuro Atoll, southern part | on page 73 |

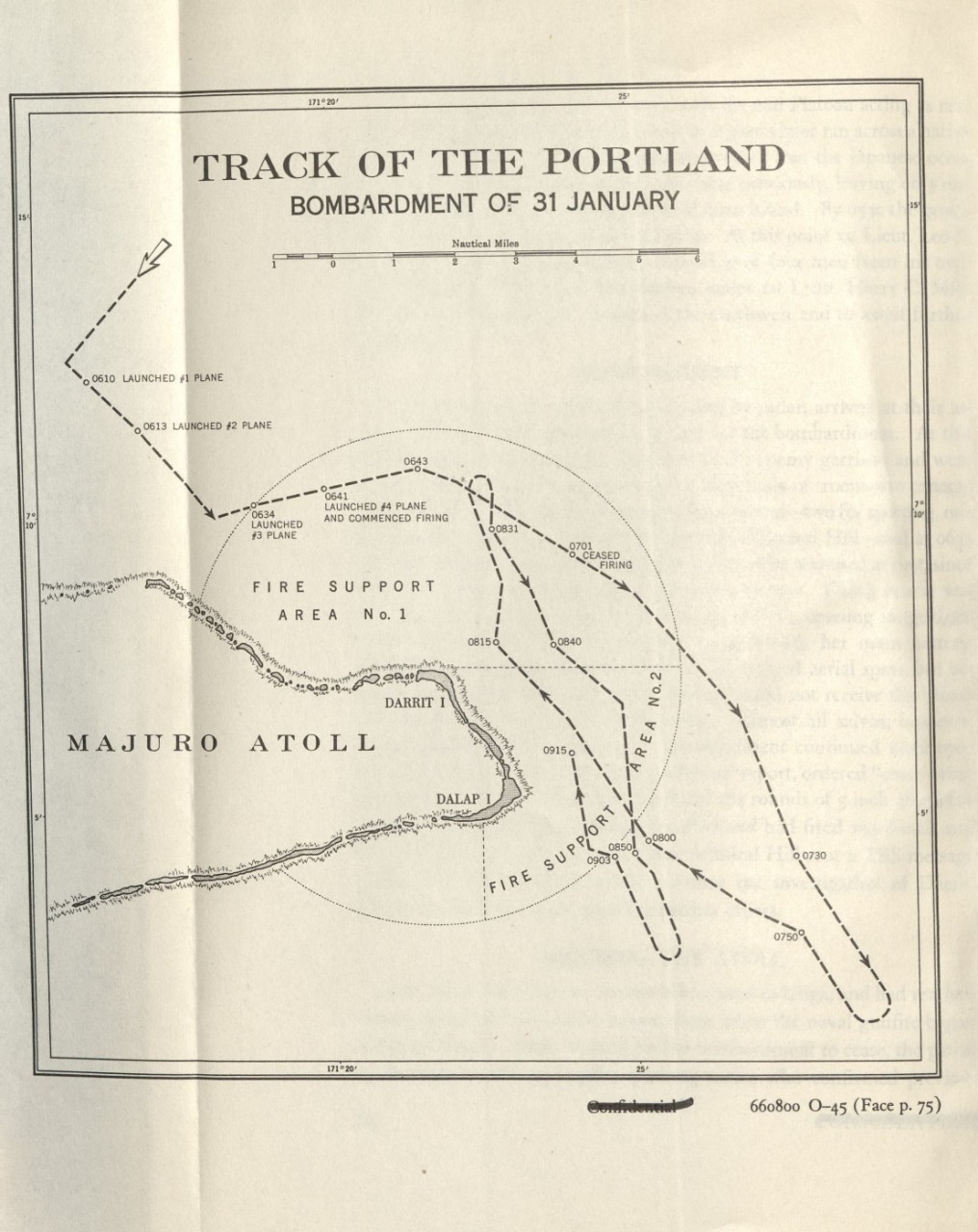

| Chart: Track of the Portland | 75 |

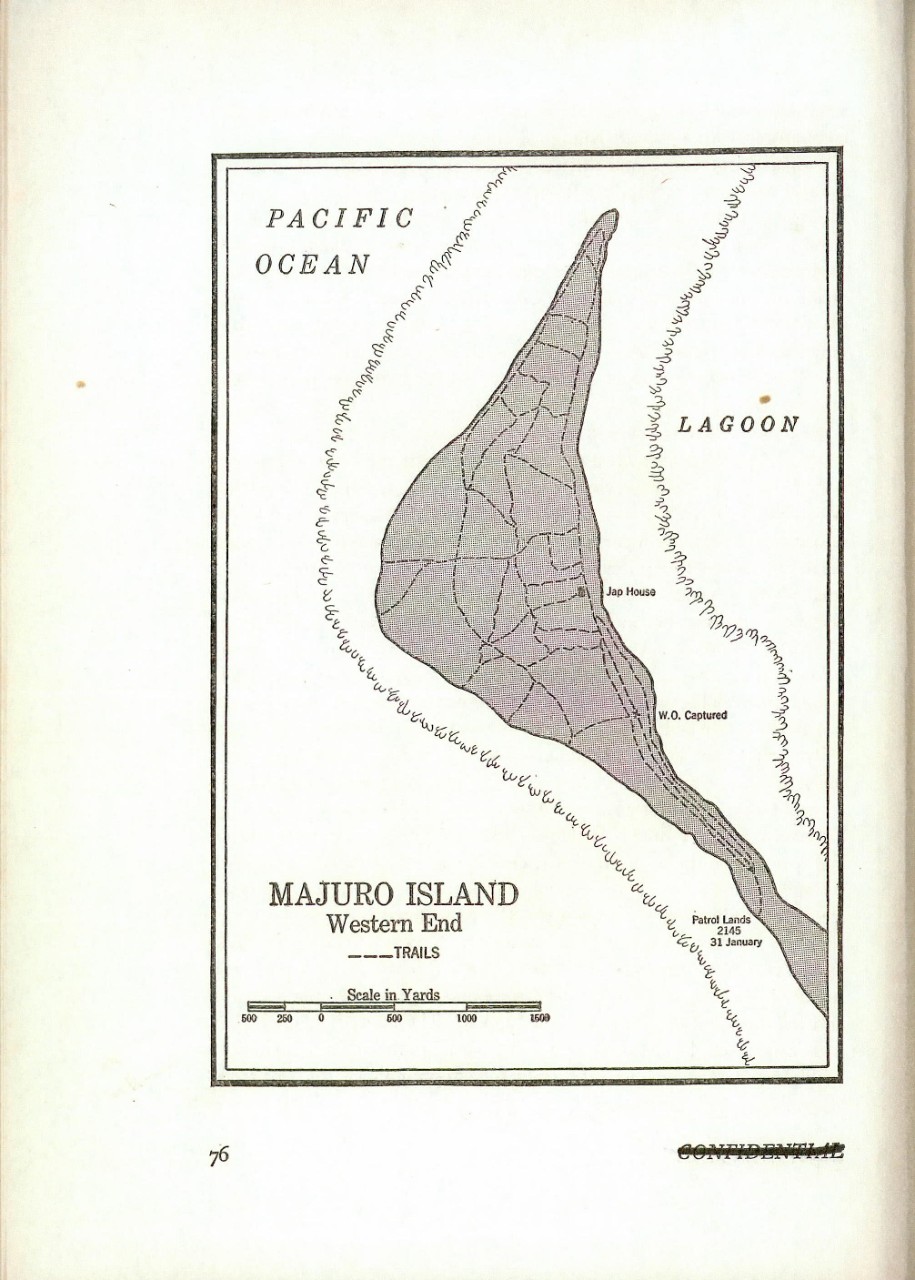

| Chart: Majuro Island, western end | on page 76 |

CONFIDENTIAL

IV

Contents

| Page | |

| Preparations | 1 |

| The Marshall Islands | 1 |

| The Plan | 6 |

| Genesis of the Plan | 6 |

| Command and Organization | 8 |

| Basic Assumptions | 9 |

| Development of Bases in the Gilberts | 10 |

| Preliminary Air Operations | 11 |

| Training and Rehearsals | 13 |

| The Task Forces Depart | 16 |

| Task Force Turner | 16 |

| Task Force Conolly | 17 |

| Task Force Mitscher | 18 |

| The Approach | 19 |

| Strikes and Bombardments | 21 |

| Task Group Reeves (Mitscher-One) | 22 |

| Taroa, 29 January | 23 |

| Kwajalein, 30 January | 27 |

| Task Group Montgomery (Mitscher-Two) | 34 |

| Roi-Namur, 29 January | 35 |

| Roi-Namur, 30 January | 39 |

| Task Group Sherman (Mitscher-Three) | 44 |

| Kwajalein, 29 January | 45 |

| The Burns Sinks Enemy Convoy, 30 January | 46 |

| Eniwetok, 30 January | 49 |

| Task Group Ginder (Mitscher-Four) | 50 |

| Wotje, 29 January | 50 |

| Taroa and Wotje, 30 January | 51 |

| Task Force Small | 52 |

| Wotje, 29 January | 53 |

| Taroa, 29 January | 56 |

| Taroa, 30 January | 58 |

| Wotje, 30 January | 59 |

| Task Group Giffen | 60 |

| Taroa, 30 January | 60 |

| Task Group Oldendorf | 65 |

| Wotje, 30 January | 65 |

CONFIDENTIAL

V

| Page | |

| The Capture of Majuro | 69 |

| The Landings Begin | 70 |

| Bombardment | 74 |

| Securing the Atoll | 74 |

| Appendix A: Task Force Force Organization | 80 |

| Appendix B: Symbols of U.S. Navy Ships | 90 |

| Appendix C: List of Published Combat Narratives | 92 |

CONFIDENTIAL

VI

The Assault on Kwajalein and Majuro

Part One

PREPARATIONS

THE MARSHALL ISLANDS

BY THE end of November 1943 American forces had completed their occupation of the Gilbert Islands, which the Japanese had seized from the British shortly after the outbreak of war in the Pacific. The immediate effect of this operation was to shorten our southwest Pacific supply lines by hundreds of miles and, even more important, to place us in a position to threaten the remaining enemy bases in the Central Pacific.

To the northwest of the Gilberts lie the Marshall Islands, which had been under Japanese mandate for almost 25 years.1 A chart of the Pacific makes

_______________

1 These islands, possession of which was essential to our subsequent assault on the Philippines, came under the control of Japan in 1919, when the Council of Four at the Paris peace conference agreed to a Japanese mandate over all German-owned Pacific islands north of the equator. This mandate, as confirmed by the League of Nations, pledged the Japanese to refrain from the construction of fortifications and bases, to govern the islands in the interests of the natives, and to allow general supervision by the League’s Mandates Commission. During the next 20 years all these provisions were violated.

Some of the terms of the mandate were confirmed and expanded at the Washington Disarmament Conference of 1922. Among the results of this conference were an agreement to maintain the status quo regarding fortifications and bases on Pacific islands until at least 1936, and a Japanese-American treaty whereby the United States was granted certain rights in the islands, including the same rights of supervision as accrued to League members.

From the inception of the mandate, missionaries and traders had reported that Japanese construction works on the mandated islands appeared to have a belligerent cast. The cruiser Milwaukee visited Eniwetok in 1923, but no real effort was made to open the islands until 1929, when the American Government asked the Japanese to allow destroyers of our Pacific fleet to visit Kwajalein, Wotje and other points in the Marshalls, pointing out that Japanese vessels had been permitted to call at Aleutian ports. The request was refused, on the disingenuous grounds that the harbors were dangerous and pilots were not available.

Three years later, in 1932, the Japanese representative at the League of Nations was called upon for an explanation of the extensive harbor development projects and other construction works being carried out in the Marshalls. He insisted that any public works were undertaken for economic reasons only. Four more years passed, and the American Government once again requested permission for a destroyer to visit the Marshalls. He insisted that any public works were undertaken for economic reasons only. Four more years passed, and the American Government once again requested permission for a destroyer to visit the Marshalls. This time the Japanese did not even reply. In 1938 the Japanese, having resigned from the League, ceased reporting to the Mandates Commission. In 1939 the last link between the fortified islands and the western world was cut when the Japanese forbade natives to travel to Kusaie Island in the Carolines, where American missionaries were still in residence.

1

it abundantly clear why the Japanese, contemptuous of the obligations they had assumed at the Paris peace conference of 1919, proceeded so vigorously with the fortification of these islands. In a military sense, they played a role for Japan similar to that which the Hawaiian group play for the United States. Their position as a keystone of Japan’s outer defense perimeter made it evident that they would be strongly defended against any attack. By the same token their strategic value made their capture essential to our northward and westward drive toward the enemy’s homeland. The Marshalls could not safely be bypassed; their military facilities, especially airfields, were too strong to leave in our rear. In addition, some of the larger atolls provided excellent fleet anchorages and sites for bases which we could use to considerable advantage in our subsequent operations against the Carolines and Marianas. 2

West of the Marshalls are the Carolines and Marianas, which also had been strongly fortified by the enemy. The Marshall Islands, lying between 040 30’ and 140 45’ N. and between 1600 50’ and 1720 10’ E., constitute in fact an eastward extension of the Caroline Group, which in turn stretches westward almost to the Philippines. The Marshalls stand approximately midway between Wake Island to the north-northwest and the Gilbert Islands to the south-southeast.

Consisting of 34 low-lying atolls and single islands, the Marshalls run roughly in two parallel columns from north-northwest to south-southeast. The eastern row, or Radak chain, comprises 14 atolls and two islands, and since it faced the direction from which an attack might be expected was obviously the more heavily fortified. The western, or Ralik chain, has 15 atolls and 3 islands, with natural fleet facilities somewhat better than in the Radak group.3 The two chains lie approximately 130 miles apart, the average distance between each atoll in a single chain being about 50 miles. The greatest distance ---165 miles ---separates Eniwetok and Bikini, whereas Knox is only 2 miles from Mille. From Ujelang, near the northwest corner of the archipelago, it is nearly 700 statute miles to the northeastern atoll of Pokaku, whence it is approximately the same distance to Mille in the south-

______________

2The Narrative will carry the Marshall Islands operation through the capture of Majuro and up to the arrival of the assault troops at Kwajalein. A subsequent volume will cover the capture of Kwajalein.

3Two of the northern atolls of the Ralik chain, Eniwetok and Ujelang, are somewhat out of line to the westward, and are sufficiently isolated from the others so that the Japanese administered them from Ponape in the eastern Carolines.

2

east. The distance from Mille to the southwestern atoll of Ebon is about 275 miles, with another 700-mile jump to Ujelang. The total land-sea area occupied by the group is roughly 375,000 square miles.

Like the Gilberts, the Marshall atolls and islands are formed of coral built up from submerged mountain peaks. There are no volcanic islands such as are found in other parts of Micronesia. No stone other than coral is indigenous to the archipelago, and no deposits other than phosphate and guano have been discovered. Lagoons throughout the area are generally shallow, averaging 20 fathoms in depth, with flat sandy bottoms except where cones of live coral, called “coral heads,” project to the surface. Normal rise and fall of tides throughout the Marshalls is about 7 feet. Currents varying from half a knot to 1 ½ knots set westward in the northern part and eastward in the south. Normally surf breaks over the outer reefs of Marshall atolls and does not reach the beaches themselves. In stormy weather, however, it often breaks over the lower and narrower land masses, and occasional tidal waves accompanying typhoons have inundated entire islands.

The climate is of the tropical marine type. The temperature is remarkably uniform, the monthly average never deviating more than one degree from the annual mean of 81 degrees Fahrenheit. Humidity is extreme and shows little seasonal variation. Heavy precipitation characterizes the whole group, but the amount and monthly distribution differ considerably from atoll to atoll. In general, rainfall in the southern part is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year, while the northern atolls and islands get very little rain during the winter when the trade winds are often accompanied by extensive periods of fine weather. During an average day the wind is strongest at about 0600 and most moderate in the early evening.

The position and natural strategic advantages of six of the islands—three in each chain---dictated their choice as foci for the enemy’s defensive efforts. In the Radak chain, where an attack could more logically be expected to fall, his preparations were centered on the atolls of Wotje, Maloelap, and Mille. Key positions in the Ralik chain, less heavily fortified than their Radak counterparts, were Eniwetok, Kwajalein, and Jaluit. Intelligence reports indicated that especially heavy fortifications and armaments, as well as excellent airfields, were under construction and constant improvement at Wotje and at Taroa Island in Maloelap. The Ralik chain, on the other hand, apparently was regarded more as a secondary line of defense, and although its fortifications and air bases were by no means negligible, they

3

were less highly developed. The quantity of available planes according to our estimates appeared greater at the Radak bases, although accurate figures were not available. Apparently the enemy’s intention was to fly these in from the Radak atolls to Kwajalein and Eniwetok should the latter be threatened.

Kwajalein atoll, which became the objective of our main attack, is centrally located in the western Marshalls and is largest of that group. About 60 miles long, it surrounds a lagoon of almost 700 square miles with mooring ground sufficient for all the navies of the world. Although the rim contains more than 80 islands (and hummocks which pass for islands), only three areas could be said to possess any military value. At the southern end, the main Japanese installations were located on the islands of Kwajalein and Ebeye (see chart, p. 6); on the western side of the atoll the only island of military importance was Ebadon; and to the north, 44 miles

4

distant from Kwajalein Island proper,4 lay the twin isles of Roi and Namur. These latter two are joined by a spit of land, over which runs a causeway.

Kwajalein Island is crescent-shaped, approximately 2 ½ miles long by 1,000 to 2,500 feet wide. The most convenient approach to the lagoon is Gea Pass which, at the time of our attack, had been buoyed and dragged to a depth of 49 feet. A safe lagoon anchorage, consisting of 196 berths

with a depth in excess of 49 feet and with a coral and sand bottom, was available.

The islands of Roi and Namur are smaller, Roi being 1,250 yards by 1,170 yards, and Namur 890 by 800 yards. Two channels, one 13 fathoms deep, gave approach to the mooring grounds inside the lagoon. Approximately 95 berths were available at that time, with depths of from 15 to 24 fathoms. Coral heads throughout the area were buoyed.

The population of Kwajalein Atoll in 1939, when the last available census was taken, was 1,079, mostly Micronesians. Since then the Japanese had

___________________

4Throughout this narrative, the word “Kwajalein” will be used for Kwajalein Atoll. When Kwajalein Island is meant, it will be so designated

5

undoubtedly moved many of the inhabitants to other Marshall atolls. Most of the natives at that time lived in villages on the islands of Kwajalein, Roi, Ebadon, and Nell.

Passages through the reef—highly important to an invading force—numbered more than two dozen. In addition to Gea Pass, five other entrances were believed to be safe for our larger ships. These were:

(a) South Pass, between Ennylabegan and Enubuj Islands. The depth of this pass was only 3 ¼ fathoms.

(b) Bigej Channel, between Bigej and Gugegwe Islands, with a depth of 5 fathoms.

(c) North Pass, between Ennuebing and Mellu Islands, also 5 fathoms deep.

(d) Eru Pass, between Eru and Gegibu Islands, with a 9-fathom depth. Because of the prevailing east and northeast winds, this pass was especially suitable for egress from the lagoon.

(e) Onemak Pass, between Onemak and Illiginni Islands. This entrance had a depth of 20 fathoms, and was moderately free of coral heads.

The atoll has many other entrances suitable for light craft. On both sides of the western salient, particularly, are many long stretches where the reef is sunken, and depths of 2 to 6 fathoms can be found.

The problem of anchorages inside the lagoon was more troublesome, since the better holdings grounds were not necessarily located near the larger islands. The most convenient anchorage was just off Kwajalein Island, in 7 to 15 fathoms. About a quarter of the way up the lagoon, off Meck Island, was another fair anchorage, although the sudden shoaling made this somewhat dangerous. South of Roi, vessels could anchor in more than 5 fathoms, but when the wind hauled around to south of east this area was not wholly safe. Outside the lagoon ships could anchor off Eru Island in 7 fathoms of water, or off Onemak in 5 fathoms.

THE PLAN

Genesis of the Plan

Planning for the Marshalls operation began before mid-October 1943. As first set forth, our intention was “to capture, occupy, and develop bases at Wotje, Maloelap, and Kwajalein, and vigorously deny Mille and Jaluit in order to control the Marshalls.” It was proposed to assault Wotje and

6

Maloelap on 1 January 1944. The forces destined for Kwajalein would remain east of these two atolls until their capture, or at least until success was assured, when they would proceed to their attack. It was hoped this could be done on D plus 1 day.

Our experience in the Gilberts in the latter part of November led to a reconsideration of this plan. Difficulties in that operation indicated that an assault upon three strongly defended atolls was an undertaking of considerable magnitude. After further reconnaissance and study the Commanding General, Fifth Amphibious Corps, advised CINCPOA on 6 December that the forces available were insufficient for the capture of all these objectives.

Accordingly the scope of the projected operation was reduced. On 14 December CINCPOA directed the preparation of plans for the initial capture of Kwajalein Atoll, and of alternate plans for the capture of Wotje and Maloelap. D-day was now advanced to 17 January, and soon, because of the necessity of revising lower echelon plans, to 31 January.

The next development was a CINCPOA directive on 17 December designating the 7th Army Division as the landing force for Kwajalein Island in the southern part of the Atoll, and the 4th Marine Division for the assault on Roi and Namur in the northern part. The same directive introduced a new element by providing that an undefended atoll, not yet identified, was to be occupied by one battalion. Although plans for the capture of Kwajalein were thus maturing, Wotje and Maloelap were retained as alternatives and work continued on plans for their capture.

The decision between the alternative plans was indicated by a CINCPOA Joint Staff Study issued 20 December, which committed us to the capture of Kwajalein. Wotje and Maloelap were to be neutralized by bombing, by carrier attacks, and by surface bombardment, while the effectiveness of enemy air bases on other atolls was to be reduced by our air attacks. A directive of the 23rd named Majuro as the undefended atoll which was to be occupied, and assigned the 1st Marine Defense Battalion for that task. Although the capture of Eniwetok was not prescribed in any major directive, plans were drawn up for a landing on that atoll in case the capture of Kwajalein should prove sufficiently rapid to justify a further move to the west. This was the final decision as to objectives, and it remained only to develop the plan and apply it through the lower echelons.

It was believed that this attack on Kwajalein would achieve speedier success with fewer casualties than would an assault on Wotje and Maloelap,

7

providing we were able simultaneously to interdict the air facilities at the latter two atolls. The attack would have a far greater chance of achieving tactical surprise. Possession of Kwajalein and Eniwetok would isolate the Radak garrisons, which thereafter could be taken at leisure or disregarded. Finally, the seizure of the Ralik atolls would give us the best fleet anchorages in the Marshalls and would place our advance air bases just so much nearer to the enemy’s inner defense ring.

Command and Organization

Supreme command for the operation, under CINCPAC, was vested in COMCENPAC, Vice Admiral Raymond F. Spruance. The Joint Expeditionary Force was commanded by Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Commander Fifth Amphibious Force. Under him, the Expeditionary Troops (Assault and Garrison Forces) were commanded by Maj. Gen. Holland M. Smith, USMC, Commanding General, V Amphibious Corps. The Joint Expeditionary Force was broken into several subordinate forces corresponding to the objectives to be captured.

The Expeditionary Force was protected by a fast carrier force assigned to Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher. This also was subdivided into appropriate forces. A neutralization force was commanded by Rear Admiral Ernest G. Small. Defense forces and land-based air were under Rear Admiral John H. Hoover.

The organization in brief,5 then, was as follows:

Fifth Fleet: Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance:

Joint Expeditionary Force: Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner:

Expeditionary Troops: Maj. Gen. Holland M. Smith, USMC.

Support Aircraft: Capt. Harold B. Sallada.

Southern Attack Force (Kwajalein): Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner.

(1 AGC, 4 OBB, 3 CVE, 3CA, 22 DD, 3AM, 2 DMS, 11 APA, 1 AP, 2 APD, 3AKA, 3LSD, 18 LST, 12 LCI(L), 6 LCT, 5 SC, 4YMS, 3AT).

Southern Landing Force: Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, USA.

7th Army Division plus assigned units: 21,768 officers and men.

Garrison and Advance Base Force: 3rd and 4th Army Defense battalions, 13,326 officers and men.

Advance Transport Unit: Capt. John B. McGovern.

Southern Transport Group: Capt. Herbert B. Knowles.

Fire Support Group: Rear Admiral Robert C. Griffen.

Carrier Support Group: Rear Admiral Ralph E. Davidson.

___________

5For complete task force organization see Appendix A.

8

Northern Attack Force (Roi-Namur): Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly.

(1 AGC, 3OBB, 3CVE, 3CL, 2CA, 19DD, 3AM, 4DMS, 11APA, 1AP, 1APD, 3AKA, 2LSD, 17LST, 12LCI(L), 6LCT, 5SC, 4YMS, 3AT).

Northern Landing Force: Maj. Gen. Harry M. Schmidt, USMC.

4th Marine Division plus assigned units, 20,778 officers and men.

Roi Garrison Force: elements of 15th Marine Defense Battalion, 10,885 officers and men.

Initial Tractor Group: Capt. Armand J. Robertson.

Northern Transport Group: Capt. Pat Buchanan.

Northern Support Group: Rear Admiral Jesse. B. Oldendorf.

Northern Carrier Group: Rear Admiral Van H. Ragsdale.

Attack Reserve Group: Capt. Donald W. Loomis.

Reserve Landing Force: Brig. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, USMC.

22nd Marine Regiment (Reinforced) plus assigned units.

106th Infantry Regiment (Reindorced) less 2nd Battalion plus assigned units.

Total 9,325 officers and men.

Majuro Attack Group: Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill.

Majuro Landing Force: Lt. Col. Frederick H. Sheldon, USA.

2nd Battalion 106th Infantry.

5th Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company.

Total 1,595 officers and men.

Majuro Garrison Force: elements of 1st Marine Defense Battalion, 7,165 men.

Fast Carrier Force: Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher.

(6CV, 6CVL, 8BB, 3CA, 3CLAA, 36DD).

Neutralization Force: Rear Admiral Ernest G. Small.

(3CA, 4DD, 2DM).

Defense Forces and Land-based Air: Rear Admiral John H. Hoover.

Basic Assumptions

Our planning of the operation assumed that we had sufficient air and surface strength to defeat the main Japanese fleet should it join battle, and to prevent enemy aircraft and submarines from halting our operations. It was also believed that our Marine and Army contingents, with the air and naval gunnery support available, could capture a limited number of bases in the face of any probable defense, and that these objectives could quickly be garrisoned and organized for independent defense against anything but a major comeback counterattack. Subsequent construction or rehabilitation of airfields and the establishment of land-based air forces would, it was assumed, enable us in a fairly short time to neutralize any of the surrounding islands still held by the enemy.

9

The first essential was to guard against any attempt at naval interference by the enemy. To insure this, the main combatant strength of our Pacific Fleet--fast carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers--was to be interposed as a “carrier shield force.”6 It was also fully anticipated that the great concentration of transports and supporting vessels, partially immobilized at the points of assault, would present an extremely attractive target for enemy air attack. Obviously the earliest possible neutralization of numerous air and naval bases in the area was essential to the success of the operation. In this connection it was assumed:

(1) That enemy land-based aircraft from Ponape, Eniwetok, Wake, Roi, Kwajalein, Wotje, Taroa, Mille, Kusaie, and Nauru, and enemy seaplanes from Jaluit and possibly other atolls, might attack our invasion forces.

(2) That our own land-based aircraft (Task Force Hoover)7 would be able to inhibit enemy operations from Mille and Jaluit, and reduce to minor proportions any from Nauru and Kusaie.

(3) That our carrier-based aircraft and surface vessels would so restrict attacks from any bases except Ponape that they would be ineffective.

Development of Bases in the Gilberts

To enable our land-based aircraft to carry out their tasks, it was necessary to speed up the development of our advanced bases throughout the entire Central Pacific. On 1 January our total air strength operating from the new bases in the Gilbert Islands--Tarawa, Makin, and Apamama--was 125 aircraft of all types. By the end of the month this number had been increased to 365. These planes were organized into three groups:

1. An Army bombing group consisting of 137 B-24’s, B-25’s, and A-24’s.

2. A fighter group of 130 P-39’s, P-40’s, and F6F’s.

3. A search and patrol group composed of 98 PBY’s, PBM’s PB4Y’s and PV’s.

The groups were subdivided, some planes of each type being stationed on each of the islands.

During the month of January several projects at Tarawa were completed or neared completion. These included the construction of the Mullinix Field fighter strip, a hospital and a dispensary. Several defensive gun batteries were added, aviation gasoline tanks were installed, and additional navigational buoys and moorings were placed. By the end of the month

____________

6This was the famous Task Force 58, under the command of Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher.

7“Defense Forces and Land-based Air.”

10

152 planes, including 62 medium and 36 heavy bombers, were in operation on the atoll.

On Makin the projects were even more extensive. The main runway was extended to 7,000 feet and the taxiways to 25,000 feet, while additional hard stands, aviation gasoline storage tanks, hospital facilities, and tanker moorage and fill lines were completed. Because the foundation of the Makin airfield was sand instead of coral, no heavy bombers were based there during the month, although some were staged through. Smaller bombers and fighters at Makin, however, were within range of Mille and Jaluit, and made repeated attacks on these bases.

The development of Apamama was on a slightly smaller scale. Work on the 8,000-foot runway was continued, and by the end of the month 112 planes--including most of the search planes of Task Force Hoover--were based there. In addition, gasoline storage facilities were completed and additional buoys, moorings, and tanker fill lines installed.

Preliminary Air Operations

These developments made possible the successful execution of a number of preliminary tasks specifically assigned to Task Force Hoover by COMCENPAC (Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance):

Initiate, beginning on D minus 15 day, an intensive bombing of all defended islands in the Marshalls.

Deny to the enemy, beginning on D minus 2 day, the use of air bases at Mille and Jaluit and thereafter maintain the neutralization of these bases.

Destroy enemy aircraft and air facilities on Roi, Wotje, and Taroa Islands (and on Kwajalein Island if facilities there were operational) up to and through D minus 3 day.

Conduct mining operations at Jaluit, Mille, Maloelap, and Wotje, furnishing air support at Kwajalein Island on D-day if requested.

Assist other forces engaged in neutralizing airfields at Wotje and Taroa from D minus 2 day on.

Deny to any enemy aircraft which could interfere substantially with the Kwajalein operation the use of bases at Kusaie and Nauru.

Carry out photographic reconnaissance of the Marshall atolls, as directed by CINCPAC (Admiral Chester W. Nimitz).

8. Make a close air reconnaissance of Majuro Atoll between D minus 5 and D minus 2 days, reporting observations to the commander of the Majuro attack force.

11

9. Make daily searches from D minus 7 day through D-day, search aircraft to be on their outer limits at sundown.

10. Attack enemy ships and shipping.

11. Defend our bases in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands.

12. Protect our shipping in the Gilbert-Ellice-Southern Marshalls area.

13. Provide air transportation.

In accordance with these instructions, our offensive operations during January included numerous strikes at enemy bases throughout the Central Pacific. Almost daily attacks on Mille by light bombers and fighters, with occasional sorties by medium and heavy bombers, kept the airfield on that atoll inoperative during the latter part of the month. The seaplane base at Jaluit was hit with 154 tons of bombs and effectively neutralized. On the other hand, we made only a few attacks on Kusaie and Nauru, since intelligence estimates indicated that these bases were little used.

Bases at Wotje and Maloelap underwent several attacks which were carried out against heavy opposition, including interception by as many as 35 enemy planes at one time. Enemy fighters frequently followed our bombers out to sea and attacked them. This practice was effectively stopped on 26 January when U. S. aircraft led interceptors from Maloelap into a trap where 12 P-40’s downed six of them. Because of the loss of several B-24’s in daylight attacks during the early part of the month, however, later heavy-bomber strikes were usually carried out at night. In addition to the B-24 attacks, 126 medium-bomber sorties, many at low levels, were made against these bases. Both atolls were still operational, however, until the carrier attacks at the month’s end.

Primary attention during these preliminary poundings centered on Kwajalein. This atoll was subjected to the hardest attacks of all by B-24’s and PB4Y’s, but unfortunately it was beyond the range of medium and light bombers. Roi airfield, like the installations on Taroa and Wotje, was operational until the carrier planes struck.

Because of the urgent need for neutralizing enemy shore bases in the Marshalls, operations against Japanese shipping were limited in general to attacks of opportunity by search planes. Three particularly successful anti-shipping strikes during the month were planned in advance, however. The first took place on 11 January, and was directed against vessels in the lagoon at Kwajalein. Complete surprise was achieved by the 10 PB4Y’s which made their runs at high speed and at very low altitudes. Fourteen 500-pound bomb hits on shipping were claimed, and additional hits were scored

12

on shore installations. CINCPAC estimated that two freighters were sunk and several others severely damaged. The planes obtained excellent photographs, and all returned safely.

On 11 and 13 January two more strikes were made on shipping at Maloelap and Wotje by B-25G’s equipped with 75-mm. Cannon. Both attacks were carried out at dusk from masthead height,8 nine planes taking part on each occasion. The planes flew in line abreast, first strafing shipping with their .50-caliber machine guns and 75-mm.’s, and then dropping their bombs. The attackers claimed 12 freighters and smaller craft sunk or damaged, and one destroyer damaged so badly that it was beached by its crew. All aircraft returned safely.

In all, planes of Task Force Hoover sank an estimated 16 enemy ships and damaged 30 more during the month. Most of these vessels were rather small; but of the ships reported sunk one was a merchantman of some 7,000 tons and four others were freighters of 4,000 tons. It was estimated that about half the ships sighted by search planes were attacked, and about a quarter of those attacked were sunk.

Meanwhile PBY’s and PB4Y’s carried out a number of minelaying flights over channels and anchorages in the lagoons at Wotje, Maloelap, Mille, and Jaluit. Photographic planes obtained excellent coverage of all important enemy bases, sometimes fling at low levels in the face of strong antiaircraft fire and enemy interception.

The Japanese, for their part, were not idle. During the first 3 weeks of the month they attacked our Gilbert Island bases almost nightly, usually at dusk or during moonlight. In general the raids were light and the bombing poor; but on three nights--2, 11, and 15 January--the attacks were on a heavier scale. It was estimated that the enemy on these nights flew a total of 65 sorties, during which 203 bombs were dropped. On Tarawa a machine shop was destroyed, five persons were killed, and eight planes were damaged. On Makin the damage was negligible, while on Apamama one of our PB4Y’s was destroyed and two others damaged.

TRAINING AND REHEARSALS

Training, which went on concurrently with the planning, was under supervision of the V Amphibious Corps. The 4th Marine Division and the 22nd Marines (reinforced) had already been assigned to the Corps when

_____________

8The attacks were made at such low levels that one of the aircraft caught up a Japanese flag which remained plastered to the wing until the plane returned to base.

13

planning for the operation began. The 7th Army Division and the 106th Infantry did not come under its control til 11th December, and the 1st and 14th Defense Battalions til the 15th. However, the 7th Division and the 1st Defense Battalion coordinated their training with the Corps for some time before their assignment. Training was complicated by the separation of the principal units. The 4th Marine Division was in California, while the other units were in Hawaii.

The 4th Marine Division began amphibious training in the San Diego area on 14 November. Ships assigned to the Northern Attack Force held rehearsals in the same area, maintaining close liaison with the Marine division. Plans and amphibious training were handled as joint problems, and all action taken in matters affecting both groups had the concurrence of Admiral Conolly and the Marine commander. Each regimental combat team was given a 2-weeks period of actual ship-to-shore training from transports. One of these rehearsal landings was held on the Aliso Canyon beaches off Camp Pendleton, Calif., during December. Admiral Conolly hoisted his flag on the Appalachian on 1 December, and on the 13th of the same month closed his temporary headquarters at Camp Pendleton. Since the flagship was only 40 miles from the camp, and since direct telephone and teletype communication was maintained, the close liaison with the Fourth Marine Division continued. Administrative matters were handled through the Commander, Amphibious Training Command, Pacific Fleet, who provided all facilities for training and made supply and repair arrangements.

A dress rehearsal was held at San Clemente Island on 2 and 3 January, simulating as closely as possible the actual attack. Most of the combatant vessels assigned as fire support ships bombarded the island during this rehearsal; carriers assigned to the Northern Attack Force also carried out their air support assignments.

During the training period aircraft from ComFAirWestCoast replacement groups were used in combat team and division landing rehearsals both at Aliso Canyon and San Clemente. Communications closely approximated those used during the actual operation, and the air liaison parties of the Jasco (Joint Assault Signal and Communication Operations) attached to the Marine division underwent continuous training by ComPhibPac representatives and field work with the Marines. The Division Air Liaison Party was expanded in both materiel and personnel, and was trained to

14

function as a shore-based air support control party.9 Destroyers assigned as fighter-director ships conducted tests of their communications equipment, and additional operating personnel were procured from Pearl Harbor by dispatch.

The 7th Infantry Division (reinforced) and the 22nd Marines (reinforced) held their final training exercises in the Hawaiian area. Landings were rehearsed at Kahoolawe Island and actually made at Maalaea Bay on Maui. Regimental Combat Team 106 did not participate in these exercises because of a dearth of shipping, but Battalion Landing Team 2-106, which had been designated to capture and occupy Majuro Atoll, held a landing exercise on Oahu on 14 January.

Islands on which these exercises were held were laid out to resemble the size and terrain of the objectives. After the rehearsals had ended, all forces returned to port for necessary repairs and rest before the final sortie.

When it became clear what shipping would be available for the operation, plans were prepared for the assignment of subordinate units to vessels. These were governed by certain considerations. First, troops had to be embarked according to the proposed tactical plan so as to have assault, defense, and garrison forces arrive at the target area on schedule. Secondly, supplies had to be loaded according to the scheme of maneuver. Third, there had to be assurance that excess equipment was not carried, as had been the case in previous amphibious operations. This last was accomplished by a thorough screening of the equipment lists of all units.

Loading plans were appreciably complicated by last-minute decisions to carry additional supplies and by the fact that some stores arrived at the loading points only a short time before departure. Most of these incidents were caused by units being attached to the corps too late to make complete plans. Nevertheless, these difficulties did not prevent our vessels from sailing in accordance with the following schedule:

6 January: Departure of Northern Tractor Groups10 One and Two from San Diego for Kauai, T. H.

13 January: Departure of Northern Attack Force from San Diego for Lahaina Roads.

19 January: Departure of Southern Tractor Groups One and Two from

__________

9This arrangement was made so that the Commander Support Aircraft would have sufficient shore-based communication facilities to tide him over until an Acorn (an air base organization, composed principally of construction battalion personnel) communications could be established.

10Tractor groups were constituted largely of large landing craft carrying men and equipment.

15

Pearl Harbor for Kwajalein; departure of Northern Tractor Groups One and Two from Kauai for Roi.

21 January: Departure of Majuro Defense Group from Pearl Harbor for Majuro.

22 January: Departure of Southern Attack Force from Pearl Harbor and Honolulu for Kwajalein; departure of Northern Attack Force from Lahaina Roads for Roi.

23 January: Departure of Attack Force Reserve and Majuro Attack Group in company from Pearl Harbor and Honolulu for Kwajalein and Majuro.

25 January: Departure of Majuro Garrison Group from Pearl Harbor for Majuro.

28 January: Departure of Southern and Northern Garrison Groups from Pearl Harbor for Kwajalein.

5 February: Departure of Northern Garrison Group Two from Makin for Roi.

This schedule reflected the final decision which set D-day for 31 January.

THE TASK FORCES DEPART

Task Force Turner

Task Force Turner, the Southern Attack Force, assembled for the most part in the Hawaiian area. It was a vast armada comprising many task groups and containing every type of ship needed for the projected assault. Among the larger craft included in the force were 12 transports, 4 battleships, 3 heavy cruisers, 3 escort carriers, 2 high-speed transports, 22 destroyers, 18 LST’s, 3 attack cargo vessels, and 3 LSD’s.11

The slower Tractor Groups, carrying the amphibious tractors, LVT’s and LVT (A)’s, departing from Pearl Harbor on 19 January, were followed by the bulk of the Force on the 22nd. The united force rendezvoused and fueled from tankers on the 26th, while planes from battleships and cruisers conducted antisubmarine patrol. Maneuvering was conducted daily, with all vessels reversing course as necessary to hold to the prescribed schedules of advance. The direct line from Pearl Harbor to the northward of the Marshalls was followed; and when well past Wotje and northeast of Kwajalein, the force turned about to the south-southwest, passed to the eastward of Kwajalein, and approached from the south. Combat air patrol was maintained for the last 3 days before D-day by planes from the CVE’s.

______________

11This was the greatest number of LSD’s yet put into action.

16

The tasks facing Admiral Turner (and, under him, Maj. Gen. Corlett who commanded the ground forces), were many:

(a) Before dawn of D-day, to capture the small and apparently lightly defended islands of Gea and Ninni on either side of Gea Pass. Thereafter to sweep the pass and the anchorage area immediately inside for mines and obstructions so that ships of all sizes could enter and anchor.

(b) Early on the same day, to seize Enubuj and Ennylabegan Islands, 2 and 7 miles respectively northwest of Kwajalein Island. Thereafter, to mount on Enubuj 105-mm. And 155-mm. batteries of the Seventh Division Artillery, which could readily lay barrage or area fire anywhere on Kwajalein Island.

(c) On D plus 1 day, to take Kwajalein Island by assault, the attacks to begin at the southwestern part of the island.

(d) On subsequent days, to capture the several islands lying to the north and northeast along the reef from Kwajalein Island. Some of these were believed to be defended.

(e) To coordinate these tasks and phases with those to be undertaken at Roi and Namur by the Northern Assault Force and the Fourth Marine Division.

It was anticipated that while fighting was still in progress on Kwajalein Island, the occupation of the chain of smaller islands extending north along the eastern reef of the atoll was to be started. The enemy had organized Ebeye, Gugegwe, and Bigej Islands for defense with varying numbers of troops, while the intervening smaller islands supported occasional armed parties. Ebeye was the first of these objectives, after preliminary preparation by aerial, naval, and artillery bombardments similar to those employed at the main assault points. Promptly upon completion of the capture of the atoll, the assault troops were to be evacuated and relieved by a Defense and Garrison Force.

At 1700 on D minus 2 day a Maloelap Bombardment Group, composed of three cruisers and five destroyers under Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen, was detached temporarily from the Task Force Turner to bombard the island of Taroa in Maloelap Atoll on 30 January. These ships arrived off the island in the early dawn, launched planes for preliminary spotting, and carried out the bombardment until mid-morning. They then proceeded to Kwajalein and took stations for the scheduled D-day bombardment.

Task Force Conolly

The Northern Attack Force, under the command of Rear Admiral Rich-

17

ard L. Conolly, was almost equal in power to the southern group. Among the heavier ships, it included 3 battleships, 3 escort carriers, 2 heavy cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 19 destroyers, 17 LST’s, 12 transports, 1 high-speed transport, 3 cargo ships, and 2 LSD’s.

On 6 January the LST’s of this force, with most of the amphibious tractors and the division artillery personnel embarked, departed San Diego with escorts for the island for the island of Maui, where they staged. At this time the broad outline of the assault plan was known; the actual operation orders, however, had not yet been received, and this group thus sailed without any detailed knowledge of its role in the attack.12 The main body of the task force, including the transports with combat teams and their equipment embarked, fire support ships, and escort carriers, departed San Diego on 13 January.13 The task force commander and transport commander, in the Appalachian and Dupage respectively, staged at Pearl Harbor. Other units of the force staged at Lahaina Roads.

Plans called for them to proceed directly from Hawaii to Kwajalein. On the 26th they headed into the wind while the cruisers, destroyers, and smaller craft refueled from two tankers. On D minus 1 day, four cruisers and six destroyers under Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf were detached to operate north of Kwajalein and give bombardment support to the landing operation. The main attack detachment then dropped astern and passed the atoll to the north, later reversing course to approach Roi and Namur from the west. The initial attack group, comprising six transports and suitable escort, cut the corner and proceeded directly, and early on the morning of D-day made contact with the initial tractor group which, being considerably slower, had steamed from Hawaii independently.

Task Force Mitscher

Task Force Mitscher, which included 12 carriers, 8 battleships, 6 cruisers, and 36 destroyers, comprised four task groups. The carrier strength of three of these (Task Group Reeves, Task Group Montgomery, and Task Group Ginder) assembled in the Hawaiian area, and departed between

_____________

12The final operation orders were later sent by officer messenger to Maui, where they were delivered to the ships concerned. The officers who carried the orders thoroughly instructed personnel of the LST’s and accompanying units in pertinent phases of the plan. However, according to Admiral Conolly, “late receipt of the orders of higher authority did result in the orders of all the lower echelons of command being prepared under pressure and without sufficient time for the careful study and preparation which was required.” Other task forces experienced similar difficulties.

13This force spent about 30 hours in the Hawaiian area fueling, provisioning, and embarking a few additional units.

18

16 and 19 January; the fourth, Task Group Sherman, was organized at Funafuti, and sailed on the 23rd. The mission of the force generally was to obtain and maintain control of the air in the Marshalls and provide air support for the assault and capture of Kwajalein. The vessels were to destroy enemy aircraft and installations at Kwajalein and Ebeye Islands on 29 January, and at Eniwetok on 30 and 31 January and 2 and 6 February. The plan also called for them to provide air support for the Southern Attack Force (Task Force Turner) on 4 and 5 February, as requested by Admiral Turner. Since the enemy had five principal air bases--Roi, Kwajalein Island, Wotje, Taroa, and Eniwetok--from which to contest the operation, it was decided to carry out the attack on all these bases as nearly simultaneously as possible. The isolated position of Eniwetok, and the uncertainty as to what part of the available troops would be needed to reduce Kwajalein, seemed to justify delaying the attack at that point for one day. The vast congregation of ships was also a factor in making this strategy preferable to that used in the Gilberts, where our carriers had attacked some of the enemy bases and assumed a defensive role with regard to others.

Among the airfields which might affect the situation, Ponape, as far as was known at the time, was little used and comparatively inactive. Eniwetok was not highly developed, but was quite important as a staging point between Truk, the Marshalls, and Wake. A second possible staging point to Wake was through Marcus and Chichi Jima. Wake itself had not been active for several months, but it was within medium-bomber striking distance of Kwajalein and the amphibious force approach routes, and had to be watched. Roi, Taroa, and Wotje were all active, and the first two were the most important fields in the Marshalls. The air base on Kwajalein Island had never been completed, but could be used for emergency landings. Mille and Nauru were usable by planes; but neither had been active for some weeks, the former because of repeated bombings and the latter because its geographical position made it difficult to supply and support. The field at Kusaie had not been completed, and the Jaluit seaplane base although usable, had recently been inactive.

THE APPROACH

Departure of the various task forces and groups from their respective staging points was accomplished generally on schedule. Such minor deviations as occurred were so unimportant as to have no effect on the operation plans.

19

For the force as a whole, passage to the assault areas was uneventful. The CVE’s of the northern carrier group, however, suffered a series of unfortunate incidents. The first happened to the Sangamon on 25 January.

During the day, the Sangamon had been conducting routine patrols. At 1651 an F6F, while landing, crashed through barriers No. 2 and No. 3 and into a group of planes parked forward. Fire broke out immediately. As a result of the crash, one SBD was knocked over the side and three F6F’s were damaged beyond repair and had to be jettisoned. The fire was soon brought under control with minor damage to the flight deck. Seven men died, nine were seriously burned or injured, and many more sustained minor injuries. The multiple collision sent 15 men overboard; of these, 13 were picked up by accompanying destroyers, and 2 were listed as missing.

A second stroke of bad luck befell the same carrier later that day. At 1816 a TBM crashed through No. 1 barrier--the other two being still out of commission--and ploughed into parked planes. Three SBD’s and one TBM were damaged beyond ship repair facilities, and three more SBD’s were damaged to a lesser extent. Luckily the second accident caused no serious personnel injuries.

The third mishap took place the following day. At 1553 that afternoon the Suwannee turned right to take station for recovery of a group of planes on antisubmarine patrol. At the same time the Sangamon made a turn to the left in accordance with the zigzag plan, and they collided. At the beginning of the turns the vessels were approximately 1,800 yards apart. Both were backing full at the moment of collision, and fortunately the damage was minor. Aboard the Suwannee, the more seriously hurt of the two vessels, the first 20 feet of the flight deck were buckled inboard for 4 feet, carrying away the port catwalk aft to 40-mm. Platform No. 2 and piercing the hull down to the main deck. Both ships were able to continue operations without interruption.

At 2000 on the 30th the Sangamon, Suwannee, and Chenango, escorted by the destroyers Farragut, Monaghan, and Dale, were detached to operate north of Kwajalein and render air support for the landings according to plan. At 2100 the main northern attack detachment14 dropped astern and passed north of and beyond the atoll, then reversed course to approach the Roi-Namur area from the west. The initial attack group,15 cutting the

__________

14Dupage, Wayne, Elmore, Doyen, Aquarius, Bolivar, Sheridan, Calvert, LaSalle, Alcyone, and Gunston Hall, with screen.

15Callaway, Sumter, Warren, Biddle, Almaack, and Epping Forest, with escort.

20

corner proceeded more directly, and at 0330 on D-day made contact near the beaches with the initial tractor group which, being slower, had proceeded from Hawaii independently.

Carrier support planes for the southern force also encountered minor difficulties. Since the line of advance was generally downwind, this group left the formation each day to conduct flight training exercises, practicing machine gun firing on a towed sleeve, radar tracking and calibration, hunter-killer tactics, simulated air attacks on vessels of the southern force, aerial free gunnery, and strafing and glide bombing on towed sleds. The frequency of these operations, together with the basic downwind course and the limited speed of the CVE’s, often made it impossible to maintain visual contact with the main body. In several instances, in fact, return to the formation could not be effected until late at night or early in the morning.

During the last 3 days of the passage these planes maintained combat air and antisubmarine patrols during daylight. In the late afternoon of the 30th , three torpedo bombers from the Manila Bay, at that time on antisubmarine patrol, were directed to cooperate with the force destroyers in a hunter-killer operation on a submarine contact about 20 miles from the center of the task force. The submarine (if it was such) was not found. Unfortunately one pilot became confused as to his position, and although released by the controlling destroyer, remained on station too long. While making his landing approach to the carrier, he apparently ran out of fuel, and in attempting a water landing spun into the sea. Immediately following the crash the plane’s depth bombs exploded. The pilot was rescued by the Caldwell, but the two crew members were never recovered. One Corregidor pilot on antisubmarine patrol became lost, and finally landed on the Belleau Wood some 100 miles distant.

STRIKES AND BOMBARDMENTS

The four carrier task groups under the over-all command of Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher began their attacks at dawn on D minus 2 day. Three of these groups, approaching from the southward and westward, struck at the airfields on Roi, Kwajalein Island, and Taroa. The fourth group, which approached from the east-northeast, hit Wotje. This route was chosen to furnish additional air cover for the transports and LST groups which were to occupy Kwajalein.

To prevent the enemy from using his fields at Roi, Wotje and Taroa after the D minus 2 day carrier strikes, intermittent bombardment was instituted by surface ships.

21

By 0500 29 January (D minus 2 day), the four task groups comprising the carrier force were in position to begin their initial attacks. Task Group Reeves, with three carriers, three battleships, one cruiser and nine destroyers, was approximately 100 miles southwest of Taroa. Task Group Ginder, with three carriers, three cruisers, and eight destroyers, was operating 50 to 100 miles northeast of Wotje. The other two groups--Task Groups Montgomery and Sherman--were within striking distance of Kwajalein Island to the south. All told, Task Force Mitscher had more than 700 planes ready to hit the enemy’s four major bases; opposition forces were believed to number no more than 160 aircraft. Our entire task force was concentrated in an area having a diameter of 300 miles, and could therefore be quickly combined in the event of interception by Japanese ships.

The primary mission of these groups was to gain control of the air over and near the assault targets and to neutralize enemy airfields at Taroa, Wotje, Roi, Kwajalein Island, and Eniwetok. This they successfully accomplished, shooting down 27 enemy planes, destroying 128 on the ground and water, and demolishing runways and air installations so thoroughly that not a single airborne enemy plane was seen after the first day’s action. In addition, planes and ships of the task force sank a large oiler, seven cargo vessels (two of which may have been escort craft), one escort ship, and several smaller vessels.

The operations of the several task groups will now be considered individually.

TASK GROUP REEVES (MITSCHER-ONE)

Task Group Reeves, Rear Admiral John W. Reeves, Jr.

Two aircraft carriers:

Yorktown (FF) (Air Group 5), Capt. Joseph J. Clark.

Enterprise (F) (Air Group 10), Capt. Matthias B. Gardner.

One small aircraft carrier:

Belleau Wood (Air Group 24), Capt. Alfred M. Pride.

Three battleships, Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr.:

Washington (F), Capt. James E.

Massachusetts, Capt. Theodore D. Ruddock, Jr.

Indiana (ComBatDiv 8, Rear Admiral Glenn B. Davis), Capt. James M. Steele.

One light cruiser (AA):

Oakland (F, CL and DD’s), Capt. William A. Phillips.

22

Nine destroyers:

Clarence K. Bronson (ComDesRon 50, Capt. Sherman R. Clark), Lt. Comdr. Joseph C. McGoughran.

Cotten, Comdr. Frank T. Sloat.

Dortch, Comdr. Robert C. Young.

Gatling, Comdr. Alvin F. Richardson.

Healy, Comdr. John C. Atkeson.

Cogswell, Comdr. Harold T. Deutermann.

Caperton, Comdr. Wallace J. Miller.

Knapp, Comdr. Frank Virden.

Ingersoll, Comdr. Alexander C. Veasey.

Taroa, 29 January

This group, carrying the task force commander, topped off its destroyers in the vicinity of latitude 040 N., longitude 1670 45’ E., on 28 January. The formation then proceeded north through the Ralik chain, arriving at the initial launching point for its attack on Taroa (latitude 070 27’ N., longitude 1700 23’E.) shortly before 0530 on the 29th, without having been discovered by the enemy. At this time flying weather was miserable; the sky was almost completely overcast, and squalls covered the sea. However, since the quick success of the entire operation depended heavily upon simultaneous strikes on all target airfields, the launchings were carried through as scheduled.

Sorties from all three carriers began almost concurrently. The initial strike, comprising 31 fighters and 1 torpedo plane, took off from the Enterprise. Aboard the Yorktown, torpedo bombers were launched beginning at 0530. This vessel’s prearranged launching course was at that time 300 out of the wind, which was blowing with a force of 10 knots. Efforts were made to counteract this, but her first planes were launched directly into the midst of fighters taking off from the Enterprise. Hardly had the first three TBF’s left the Yorktown’s deck when the Enterprise cut across the Yorktown’s bow and launching was interrupted for several minutes. After the next group of four was launched, the ships ran into a heavy rain squall, and further launching had to be postponed until it cleared. At 0535 the squall lifted; by this time, however, the engines of the idling planes were badly loaded up, and after one successful launching a plane crashed off the Yorktown’s starboard bow. Its crew was rescued by the Gatling, but the remainder of the flight was canceled.

The two breaks in the launching interval made it extremely difficult to rendezvous under unfavorable weather conditions. Three Yorktown

23

planes proceeded to the rendezvous sector after getting clear of the Enterprise group, but could find no other torpedo aircraft. Fighters from the Belleau Wood, tailing each other around the area, did not yield the lead to the VT flight leader, and the entire formation drifted 30 miles to the west of the task group, leaving a rainstorm in between. The three torpedo planes then departed for the target. After proceeding about 20 miles they overheard radio instructions ordering another member of the group to rendezvous over the base, so they returned and picked up three of their fellows. The six VT’s finally took departure at 0700, together with VB’s VF’s and VT’s which had been launched at 0630 for a second strike.

The VT’s, arriving over Taroa shortly before 0800, made glide attacks from 11,000 feet. Four of them dropped their bombs in the aircraft dispersal areas, probably damaging three Bettys and one single-engine plane on the ground. All encountered intense and accurate antiaircraft fire, but escaped damage. Planes of the accompanying second strike---four F6F’s and twenty SBD’s--- carried out their attack simultaneously. The bombers hit the aircraft repair shop and torpedo workshop area heavily, while the fighters, after covering the bomber attack, strafed aircraft on the field and small vessels in the lagoon. A building believed to be a torpedo workshop was destroyed, and repair shops and unidentified buildings were damaged. One large ammunition magazine was set afire and later exploded, the smoke rising to 5,000 feet. An enemy fighter was thoroughly strafed, as were three or four small vessels, one of which caught fire. Two schooners were also strafed, and one set afire.

The next Yorktown strike---nine F6F’s and six TBF’s---was launched at 0730, but found the target covered with clouds and had to delay its attack until openings could be located. They dropped most of their bombs in aircraft parking areas, destroying one single-engine plane and probably destroying three Bettys. An explosion and fire broke out among buildings south of the runways. The fighters, finding no enemy aircraft airborne, strafed grounded planes, setting fire to two Bettys and thoroughly peppering eight more Bettys and one fighter. One of our TBF’s was hit by antiaircraft fire, and plunged in flames into the water south of the island.

Meanwhile planes from the Enterprise were running into opposition. That vessel’s first wave, as it arrived over Taroa, met seven enemy interceptors, both Zekes and Hamps. They shot down four and probably destroyed two more. Five Bettys and 12 to 15 fighters were demolished on the ground, and airfield facilities were thoroughly strafed. Eighteen bombers from the

25

same carrier dropped 6 1/2 tons of high explosive on Japanese buildings, torpedo storage facilities, ammunition dumps, runways and dispersal areas. Thirteen torpedo bombers dropped 10 tons on the airfield area, damaging at least two grounded enemy aircraft. Four Enterprise fighters were lost---one in combat, one because of the pre-dawn operational hazards, and two which did not return and were never accounted for. Seven bombers suffered minor damage from antiaircraft fire.

The Belleau Wood, in addition to launching antisubmarine and combat air patrols to cover the task group, sent four TBF’s to attack Taroa. Each was loaded with one 500-pond and ten 100-pound general purpose bombs. These planes, which took off at 0730, proceeded into the target area with the Yorktown group, making their approach from the lagoon side and diving in a northwest-southeast direction across the island. They released their bombs at altitudes varying from 1,800 to 2,500 feet; most hit the airfield, although a few carried on out into the water on the seaward side.

Later attacks on D minus 2 day were carried out by Yorktown planes. A combat air patrol consisting of 12 F6F’s launched at 0830, destroyed three single-engine planes and one Betty on the ground, and thoroughly strafed 16 other aircraft. At 1107 11 more TBF’s took off to attack Taroa. This group was accompanied by fighter cover from the Enterprise. The special target assigned was a fuel dump, which had been observed by a previous flight, on nearby Reuter Island. The aircraft released most of their bombs in this area, and obtained thorough coverage, but unfortunately no fires resulted. One stick of bombs was also laid across a radio station on a small island about 5 miles northwest of Taroa, resulting in probable damage. Another stick was laid near the Taroa runway intersection, setting fire to one single-engine plane.

Minor operations during the day included four depth bomb attacks by antisubmarine patrol SBD’s on a small vessel in Maloelap lagoon and on one of the islands of the atoll. During the afternoon, eight F6F’s flying combat air patrol destroyed five enemy VF’s in revetments near the runway, while another of our fighters intercepted and shot down a Kate which had just taken off from Wotje.

At about 1750, approximately in latitude 080 03’N., longitude 1700 26’E., lookouts on the Enterprise sighted nine planes, flying very low, coming in over the horizon from 1200 R. Radar had not picked them up, presumably because of their low altitude which was estimated at about 100 feet. Two

26

minutes later a TBS message from the Belleau Wood reported sighting 10 aircraft, bearing 3300 T., “on the horizon."16

The task group went to General Quarters. The gunnery officer in Sky Forward on the Enterprise passed the word that the planes looked like Betttys, and both directors were ordered to get on. At the same time the gunnery liaison officer in the Enterprise Combat Information Center (CIC) spotted 10 planes “which looked like Bettys” on the starboard beam, and the combat air patrol was vectored out toward them from 1,000 feet over base.

Shortly thereafter, Enterprise lookouts identified the planes as B-25’s but not before two rounds had been fired from the after director. Cease firing was ordered immediately; but unfortunately other ships of the formation saw the splashes and opened fire. Word was immediately broadcast over TBS “do not fire, planes are friendly,” and similar information was sent out over VHF to the combat air patrol. The word, however, was received too late; not until the leading pilot had fired several bursts at the nearest B-25 did he recognize the planes as friendly, and order his wing men to cease fire. The bomber began to smoke, and glided into the water about 6 miles ahead of the task group. Two destroyers were sent to the scene, and picked up all the personnel except the navigator, who went down with the plane.

The copilot of the plane said his formation had sighted the task group some time before it opened fire, and that immediately upon making contact the planes turned to the right. He added that they turned right a second time just before the Enterprise opened fire. At least three of the planes, he said, had their IFF turned on, adding that he personally was flashing the recognition signal with an Aldis lamp when fire was opened. Surface observers agreed that the planes did turn right from a closing course to one paralleling the task group. When abeam, or slightly forward of abeam, however, the planes turned toward the group, crossing its course at an angle of about 300, and passed ahead and off to port.

Kwajalein, 30 January

Upon completion of the Taroa strikes, the task group steamed southwest toward Kwajalein, where Kwajalein Island and neighboring islets were to be its objectives for the remainder of the operation.17 The night passed

____________

16Personnel in the Enterprise CIC stated that the Belleau Wood’s transmission was somewhat garbled; all thought they heard the word “Bettys.”

17Task Group Sherman had already hit these targets. See p. 45.

27

uneventfully, without contacts or alerts. The group’s carriers had scheduled a pre-dawn launching for 0630 on the 30th to cover the surface force bombardment which was to neutralize the Kwajalein Island airfield; frequent rain squalls over the area, however, forced a postponement. The first Enterprise strike was launched at 0735; a Yorktown combat air patrol was airborne at 0809; the Belleau Wood strike took off at 1330.

The surface bombardment, however, proceeded on schedule, and proved highly effective. The bombardment group, composed of the Washington (CTU), Indiana, Massachusetts, Cogswell, Caperton, Ingersoll, and Knapp, departed from the remainder of the task group at 0715 in latitude 08 degrees N., longitude 1670 30’ E., and steamed on course 0250 T. at 25 knots. The heavy ships were in column, with the Washington in the van and the Massachusetts bringing up the rear. Destroyers screened ahead in the following formation: Cogswell, station No. 1, 3,500 yards, 0250; Ingersoll, station No. 2, 3.500 yards, 3350; Knapp, station No. 3, 4,000 yards, 0650; Caperton, station No. 4, 4,000 yards, 2950. Battleships were to be prepared to open fire on Kwajalein Island at maximum range during the approach, using high capacity projectiles and service charges, salvos to be controlled by CTU over TBS. The primary mission of the destroyers was to screen the capital ships; simultaneously they were to work over the smaller islands of the atoll and take under fire selected targets of opportunity. The bombardment itself was to be divided into two phases of 1 and 3 hours duration respectively. The early morning phase was expected to knock out any enemy air activity which might have survived the previous air strikes. During the second, and longer, phase, defensive installations such as pillboxes, ammunition dumps, and gun emplacements were to be destroyed.

After several changes of course and speed, the Washington’s radar picked up Kwajalein Island at 0907, at range of 42,500 yards. Continuing heavy squalls had decreased visibility, however, and a suitable visual point of aim could not be determined for some time. Battleships launched one spotting plane each at 0910. At 0936, the destroyers on signal formed special screen No. 1 for the approach, taking station as follows: Ingersoll 4,000 yards, 0000; Caperton 2,000 yards, 0000; Cogswell 3,000 yards, 0300; Knapp 3,000 yards, 0600.

The first shots of the bombardment were fired by the battleships. On orders from CTU, they opened at 0956 with their main batteries on Kwajalein Island. The initial salvos fell short. One minute later the Massachusetts fired a second salvo, which apparently struck home. Shortly after

28

1000, shore batteries on the north tip of Kwajalein Island began firing at the bombardment group. The first salvos passed over the Massachusetts and Indiana, and several others straddled the ships in range but were off in deflection. The battleships quickly silenced the battery, and thereafter met no enemy counter-fire. At the same time our ships sighted several enemy patrol craft in the lagoon near the battery. Although B-hour had been postponed from 1000 until 1015, the Washington and Indiana immediately opened on these vessels with their 5-inch batteries, sinking one and scoring hits on two others.

At 1016 the Washington, as guide, arrived at the open-fire position, and her secondary battery switched from the enemy ships to Ebeye Island, her scheduled initial target. Despite rather poor coverage at first, she straddled several of the beach defenses and started a fire in the hangar area. The Massachusetts and the Indiana followed suit, opening with their main batteries on defensive installations in the north and central sectors of Kwajalein Island. At 1027 the Washington, continuing up the eastern side of the atoll, shifted to Gugegwe with her 5-inchers, and worked over that island for 11 minutes. As before, enfilading fire was not possible because of the angle of the shoreline, yet it was necessary to fire on this leg of the course to obtain air spots. After the bombardment of Gugegwe had begun, the Washington sighted a tanker in the lagoon behind the island, and opened on it with two port mounts for four salvos before it was lost to sight. No results were visible, and fire was shifted back to Gugegwe.

The destroyers opened after the battleships. The Ingersoll, in the van, began bombarding Gugegwe at 1020 while she was screening the Washington. Nine minutes later she shifted her fire to Bigej, ceasing at 1033 when the Washington fouled the range. At 1055 the destroyer resumed fire on Gugegwe, ceasing at 1105 when her range was again fouled. The Caperton, 2,000 yards behind the Ingersoll, expended 100 rounds on two small unnamed islets between Ebeye and Kwajalein Island. The Cogswell left the formation at 1037 and proceeded separately to bombard the southern portion of Gugegwe. She took the target under fire at 1041 at 9,000 yards and covered her sector fairly well until 1056, when she shifted fire to one of the islets the Ingersoll had hit. At 1114 she had to withdraw to resume her screening station on the Washington. The Knapp, after a brief period of fire at targets of opportunity north of Kwajalein Island, began firing at one of the unnamed islets at 1101 and ceased at 1105, whereupon she maneuvered eastward to resume her station screening the battleships.

29

The second phase of the surface bombardment, during which the battleships operated independently, opened promptly at 1200, when the Indiana’s main battery began firing at Gugegwe. Shortly after 1210 the Massachusetts opened on Ebeye, while the Washington commenced firing on the western end of Kwajalein Island at 1226. Because of delays during the inter-phase bombing, the Washington made her run to the south at a speed of 20 rather than 12 knots as planned, and decreased her salvo interval to 1 minute.

Between 1200 and 1230 the Indiana fired 81 rounds of 16-inch, although she was scheduled to fire only 63 rounds. The two extra salvos were fired because the hitting gun range had been established, and effective coverage of good targets appeared likely. At 1300 the Indiana resumed fire on the center and west of Kwajalein Island. The latter part of this phase comprised an indirect enfilade fire on the extreme western end of the island. Spotting was difficult since the entire area was ablaze and covered with smoke. Because of the extra rounds she had expended on Gugegwe, the Indiana decided to reduce the number fired at Kwajalein Island. Most salvos, however, landed in the assigned areas. Between 1402 and 1420 her port battery fired almost 600 rounds of 5-inch antiaircraft common into Ebeye, starting a large blaze. At 1424 she opened on the center and west of Kwajalein Island, continuing until 1448 at which time all fire ceased.

The Massachusetts, between 1210 and 1234, fired 23 salvos on Ebeye. At 1241 she shifted to Kwajalein Island, scoring hits in the middle of the airstrip, and ceased main battery fire at 1341 after 34 more salvos. At 1425 she opened with her secondary battery, and ceased at 1458. She then recovered her spotting aircraft and proceeded to the rendezvous.

The Washington ceased main battery fire at 1250, after expending 66 rounds and starting fires in her assigned areas on Kwajalein Island. From 1240 to 1250 her port 5-inch battery also fired on beach defenses on the southwestern shore of Kwajalein Island and on inland shore batteries, starting one large fire. At 1251, after a reversal of course, her starboard 5-inch mounts opened on the beach defenses at the island’s western tip. Again the coverage was effective, and fires and explosions occurred until the end of this phase at 1317. The main battery director picked up Ebeye immediately after ceasing fire on Kwajalein Island. Fire was opened at 1256, and a quick run was made with almost perfect conditions of enfilade. After a period of concentration on the seaplane apron and adjacent areas, fire was shifted to the southern portion of the island, which had not been

30

previously covered. A total of 36 rounds was fired during this phase, 32 of them detonating in the assigned area. Hangars and shops were set afire, and an antiaircraft battery on the north end of the island was silenced.

Following a spotter’s report that a heavy gun emplacement was located on the southeastern tip of Enubuj, the Washington began main battery fire on that point at 1320. Considerable difficultly was experienced during this firing because a definite point of aim was lacking and the target was extremely narrow. At 1327 the secondary battery opened for 4 minutes on an LST-type vessel anchored north of the western tip of Kwajalein Island. The second salvo hit, starting a small fire and buckling the craft amidships. Main battery fire was shifted from the southern tip to the central section of Enubuj at 1330. Again the narrow profile of the island presented difficulties, but the radio station and adjoining structures were seriously damaged, one large tower being toppled and several buildings left in flames. Fire on Enubuj was interrupted at 1351 to engage active batteries on Kwajalein Island. After silencing these with 5-inch and 16-inch shells, the Washington divided her fire, bombarding Enubuj with the forward turrets while turret No. 3 and the 5-inch battery covered the western beach areas on Kwajalein Island until 1407.