A photocopy of this document is in the Navy Department Library. The original document is located in the World War II Command File of the Operational Archives Branch, Naval History & Heritage Command.

The Navy Department Library

Amphibious Operations

Capture of Iwo Jima

16 February to 16 March 1945

THIS PUBLICATION AND THE INFORMATION

CONTAINED HEREIN MUST NOT

FALL INTO THE HANDS OF THE ENEMY

[Formerly secret, subsequently declassified in accordance with OPNAVINST 5513.16.]

UNITED STATES FLEET

Headquarters of the Commander in Chief

**********

UNITED STATES FLEET

HEADQUARTERS OF THE COMMANDER IN CHIEF

NAVY DEPARTMENT

WASHINGTON 25, D.C.

17 July 1945.

This publication "Amphibious Operations--Capture of Iwo Jima--16 February to 16 March 1945" continues the series promulgating timely information drawn from action reports. It follows "Amphibious Operations--Invasion of the Philippines, CominCh P-008."

Material contained herein has not been subjected to exhaustive study and analysis, but is issued in this form to make comments, recommendations, and expressions of opinion concerning war experiences readily available to officers engaged or interested in amphibious operations. It should be widely circulated among commissioned personnel.

This publication is classified as secret, [Declassified in accordance with OPNAVINST 5513.161] nonregistered. It shall be handled as prescribed by Article 76, U.S. Navy Regulations, 1920. When no longer required it shall be destroyed by burning. No report of destruction need be submitted.

This publication is under the cognizance of, and is distributed by the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

Transmission by Registered Guard Mail or U.S. registered mail is authorized in accordance with Article 76 (15) (e) and (f), U.S. Navy Regulations.

B.H. BIERI,

Acting Chief of Staff.

--I--

CONTENTS

| Chapter I. Narrative: | Page | ||

| Covering Force | 1-1 | ||

| Effect of Operations Preceding and Following Iwo Jima | 1-1 | ||

| Supporting Forces | 1-2 | ||

| Effect of Weather | 1-2 | ||

| Aircraft Losses, Task Force Fifty-eight | 1-3 | ||

| Joint Expeditionary Force | 1-4 | ||

| Composition | 1-4 | ||

| Summary of Ships | 1-5 | ||

| Strategical Concept | 1-6 | ||

| Narrative from 19 February to 26 March | 1-7 | ||

| Amphibious Support Force | 1-11 | ||

| Organization | 1-11 | ||

| Narrative from 16 to 19 February | 1-11 | ||

| Expeditionary Troops | 1-15 | ||

| Enemy Defensive Tactics | 1-15 | ||

| Limitations of Supporting Arms | 1-15 | ||

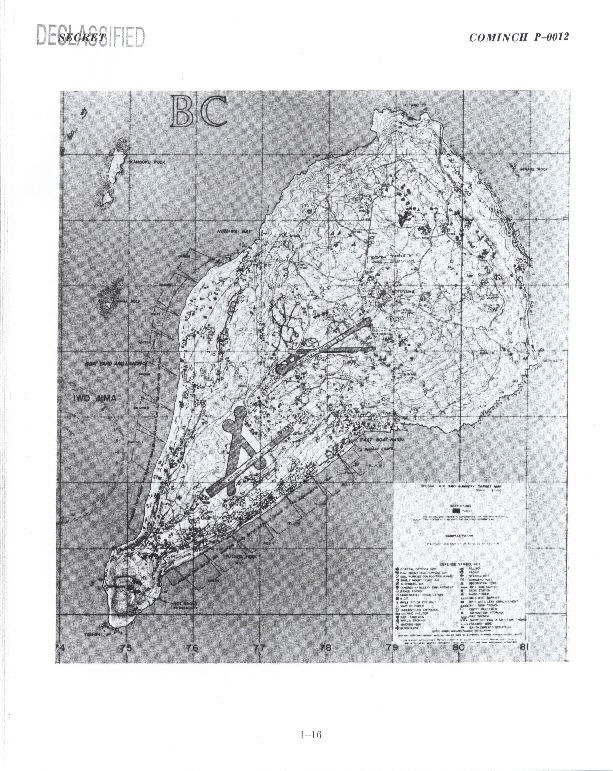

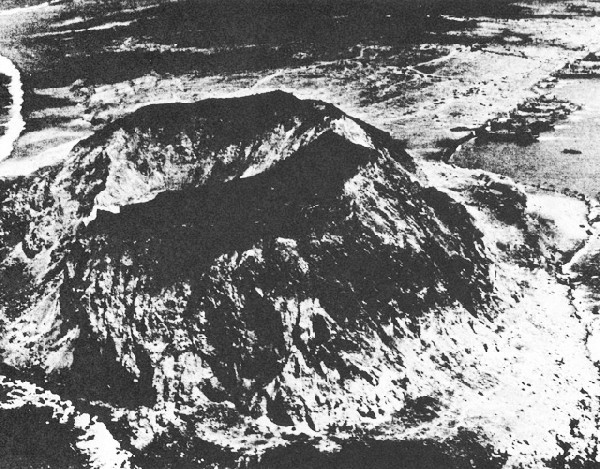

| Map of Iwo Jima | 1-16 | ||

| Chapter II. Naval Gunfire: | |||

| Preliminary Bombardment Results | 2-1 | ||

| Preliminary Bombardment Requested | 2-1 | ||

| Preliminary Bombardment Plan | 2-1 | ||

| Function of Amphibious Support Force | 2-2 | ||

| Rolling Barrage | 2-3 | ||

| Shore Fire Control Communications | 2-3 | ||

| Air Spot Plan | 2-4 | ||

| Call Fires | 2-4 | ||

| Illumination | 2-4 | ||

| Close Support for Landing | 2-5 | ||

| Gunboats, LCI(G)'s | 2-6 | ||

| Mortar LCI's | 2-7 | ||

| Close Range Destructive Fires | 2-8 | ||

| LCI Mortar Plan | 2-10 | ||

| Effect of Bombardment | 2-10 | ||

| Ammunition Expenditures | 2-11 | ||

| Illustrations | 2-13 | ||

| Chapter III. Air Support: | |||

| Preliminary Air Bombardment | 3-1 | ||

| Purpose | 3-1 | ||

| Effects | 3-1 | ||

| Coordination of Surface and Air Bombardment | 3-1 | ||

| Effectiveness of Air Weapons | 3-1 | ||

| Command Organization | 3-2 | ||

| Air Support Operations | 3-2 | ||

| CVE's Available | 3-2 | ||

| Time to Execute Missions | 3-2 | ||

| Landing Force Air Support Control Unit | 3-3 | ||

| OY Observation Planes | 3-3 | ||

| Coordination Between Air, Naval Gunfire and Artillery | 3-3 | ||

| Brodie Device | 3-3 | ||

| Night CAP | 3-5 | ||

| Napalm Bombs, Functioning of | 3-6 | ||

| Communications | 3-6 | ||

| Chapter IV. Intelligence: | |||

| Air Target Folders | 4-1 | ||

| Mobile Hydrographic Unit | 4-1 | ||

| Salient Features of Defense | 4-2 | ||

| Surf Forecasting | 4-3 | ||

| Magnetic Properties of Iwo Jima Sand | 4-3 | ||

| Chapter V. Ship to Shore Movement: | |||

| Underwater Demolition Team Beach Reconnaissance | 5-1 | ||

| Effects of White Phosphorus Smoke | 5-1 | ||

| Control Organization | 5-2 | ||

| Radar Navigational Device | 5-3 | ||

| Shore Parties | 5-4 | ||

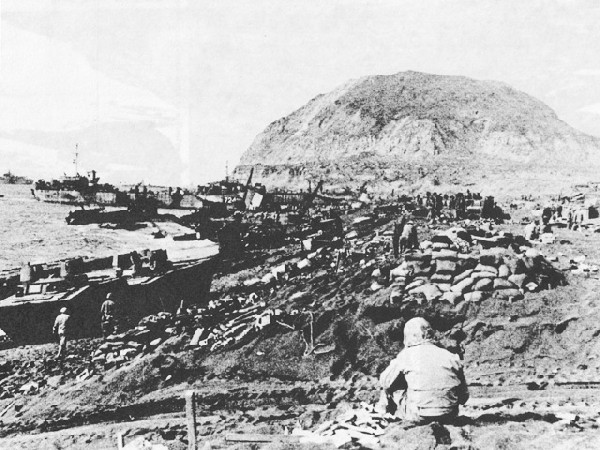

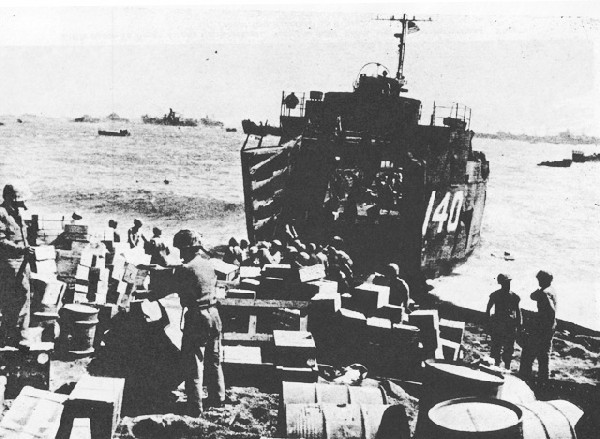

| Execution of Ship to Shore Movement | 5-4 | ||

| Beach Parties | 5-5 | ||

| Unloading Delays | 5-6 | ||

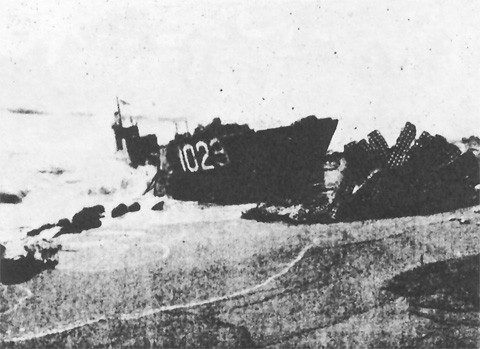

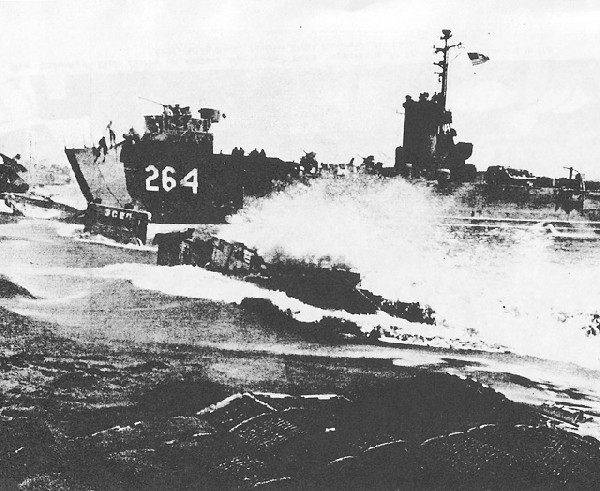

| Operation of LSM's | 5-6 | ||

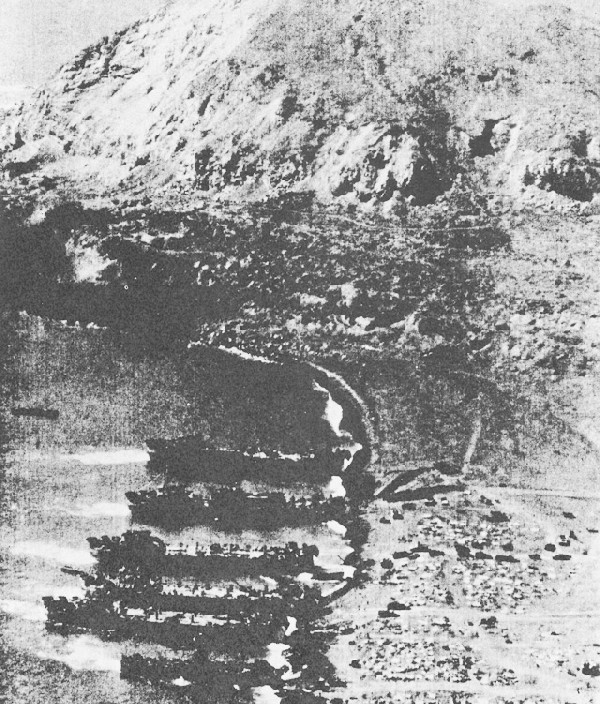

| Illustrations | 5-8 | ||

| Chapter VI. Logistics: | |||

| Effects of Volcanic Sand | 6-1 | ||

| Casualty Evacuation Ships | 6-1 | ||

| Alongside Damage | 6-3 | ||

| Resupply of Ammunition | 6-4 | ||

| Pontoon Barges and Causeways | 6-4 | ||

| Damage to LSM's | 6-4 | ||

| Pallets | 6-5 | ||

| Damage to LCT's | 6-5 | ||

| Assault Loading | 6-6 | ||

| Distribution of Troops and Material | 6-6 | ||

| Standard LST Load Number One | 6-7 | ||

| Casualties Screened by Hospital LST's | 6-9 | ||

| Summary of Naval Battle Casualties | 6-9 | ||

| Summary of Landing Force Casualties | 6-10 | ||

| Illustrations | 6-11 | ||

| Chapter VII. Miscellaneous: | |||

| Landing Craft | 7-1 | ||

| LSV | 7-1 | ||

| LSD | 7-1 | ||

| LST | 7-1 | ||

| LSM | 7-1 | ||

| LCM(3) | 7-1 | ||

| LCVP | 7-1 | ||

| LVT | 7-2 | ||

| DUKWS | 7-3 | ||

| Weasels | 7-3 | ||

| Barges and Causeways | 7-3 | ||

| LST(M) | 7-4 | ||

| Alongside Damage | 7-4 | ||

| Life Saving Devices | 7-4 | ||

| DORON Armor for Exposed Personnel | 7-4 | ||

| Smoke | 7-5 | ||

| Heavier Ground Weapons | 7-5 | ||

| Illustrations | 7-6 | ||

List of Effective Pages

| Page | |

| Letter of Promulgation | I |

| Distribution List | II |

| Table of Contents | III to V inclusive |

| List of Effective Pages | V |

| Frontispiece | vi |

| Chapter I | 1-1 to 1-16 incl. |

| Chapter II | 2-1 to 2-22 incl. |

| Chapter III | 301 to 3-6 incl. |

| Chapter IV | 4-1 to 4-4 incl. |

| Chapter V | 5-1 to 5-13 incl. |

| Chapter VI | 6-1 to 6-23 incl. |

| Chapter VII | 7-1 to 7-6 incl. |

DISTRIBUTION LIST FOR COMINCH P-0012

Standard Navy Distribution List No. 29, 15 June 1945

| List 1 | a (1) less Cominch; ComPac (5), ComThird (3), ComFifth (3); b (1); c(1); less ComFairShipLant, ComFairShip Pac, ComGenAirFleetMarForce, DirAviation, MC; d (1); e (1); g-ComPhibPac (5), ComPhibPacAdmin (5), ComThirdPhib (3), ComFifthPhib (1), ComPhibGroups (2), ComLandCraftFlot (1), PhibTra7thPhib (2), 7thPhibAdmin (1), Com7thPhib (3), ComPhibTraPac (35); h (1) less ServLantSubCom; i (1) less ComSec #115, #117, ComNorthCalifSecWesSeaFron, ComNorWesSecWesSeaFron, ComSouthCalifSecWesSeaFron; j (1); k only to COTCLant (1) COTCPac (3), ComFltTraCom, 7thFlt (1), PreComTraCenCOTCPac (6), ComSanDiego, San Pedro Shakedown Group (1); 1-only to Chief of Staff to Commander in Chief, Army & Navy (1). |

| List 2 | a-3 (1); a-10 FiarWings only (1); a-18 only to Fleet Aircraft Recog Unit (1); a-19 only to ComUtWingServ (1); f (1); g (1); n (1) less LCT Groups, o (1) MinRons only; v (1). |

| List 3 | b (1); c (1); d (1); f (1); m (1); p (1); t (1); u (1); v (1); x (1); kk (1) oo (1); rr (1); vv (1); zz (1); www (1); ffff (1); gggg (1); jjjj (1). |

| List B-3 | Construction Brigades and 36th Constr. Regiment only (1). |

Standard Navy Distribution List No. 32, 1 June 1945

| List 6 | a (1) less SevRivNavCom, Comdt PotRivNavCom, SamDefGrp; b only to CNAOpTra Jacksonville, Fla. (25)< CNATra Pensacola, Fla. (1). |

| List 7 | a-1 (1) less NYdNavy #128; d-1 (1) only to NAB's 1st to 13th ND incl., and NavAirTrBases, Corpus Christi and Pensacola; e (1); f (5); g (3); h (5); i-3 (2) only to Newport, R.I. |

| List 11 | SecNav (1); UnderSecNav (1); AsstSecNav (1); AsstSecNavAir (1); ChrmGenBd. 92); InspGen (1); BuAero (5); BuPers (10); CNO (1); BuOrd (5); BuShips (5); BuY&D (5); USMC (900); USCG (3). |

| List 14 | q (2). Plus Special Distribution. |

Numbers in parentheses indicate number of copies sent to each addressee.

The capture and occupation of the Marianas Islands gave our forces bases from which targets in the Japanese Empire could be subjected to VIR air attacks. In order to operate with greatest effectiveness and with a minimum of attrition, fighter cover for the long range bombers was required at the earliest practicable time. Iwo Jima was admirably situated as a fighter base for supporting long-range bombers between the Marianas and the Empire and offered sites for three airfields. Accordingly the Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean areas, issued his Operation Plan No. 11-44, directing the Commander Fifth Fleet, as Commander Central Pacific Task Forces, to capture, occupy, and defend Iwo Jima and develop air bases on that island, to reduce Japanese naval and air strength and production facilities in the Japanese homeland, and to protect air and sea communications along the Central Pacific axis.

The planning for and the actual execution of the Iwo Jima operation were affected to a considerable extent by the operations in the Philippines which immediately preceded it, and by the necessity of preparing for the Okinawa operation which was to follow it.

The Philippine operations necessitated last minute changes and reduced the total number of ships which had been previously allocated to the Iwo Jima operation. This applied primarily to battleships, cruisers, and destroyers for the Joint Expeditionary Force, although other forces were also affected to a lesser extent. The only source from which additional gunfire support ships could be obtained was from Task Force 58 (Fast Carrier Force). In order to provide the necessary additional battleships for gunfire support, the Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Fleet, authorized the use of the North Carolina and Washington for this purpose. These two ships were, accordingly, loaded principally with bombardment ammunition, their service allowance of armor piercing ammunition being correspondingly reduced. Certain cruisers of Task Force 58 were also loaded with some additional bombardment ammunition.

The Okinawa operation affected the Iwo Jima operation in two ways. First, it was felt that the threat of Japanese land based aircraft, while taking Okinawa, would be very great, both because of the great value of that island to us when we took it and because of its closeness to the Empire (325 miles). Therefore, anything which we could do during the Iwo Jima operation to reduce Japanese air strength, either in aircraft and, even more, in aircraft production facilities, would help the Okinawa operation as well as support the Iwo Jima operation. The second way in which the Okinawa operation and the Iwo Jima operation affected each other was in the close timing of the two operations. D-day for the Iwo Jima operation was 19 February, L-day for the Okinawa operation had been set as 1 April. If the fighting ashore on Iwo Jima were prolonged, it might be difficult to carry out the plans for the Okinawa operation which called for initial carrier operations to start of Kyushu on L-minus-14 (18 March) and off Okinawa on L-minus-9 (23 March).

Commander Fifth Fleet's Operation Plan No. 13-44 was issued on 31 December 1944. Principal commanders were assigned as follows:

Commander Joint Expeditionary Force (TF 51)--Vice Admiral R.K. Turner.

Commander Fast Carrier Force (TF 58)--Vice Admiral M.A. Mitscher.

Commander Expeditionary Troops (TF 56)--Lt. Gen. H.M. Smith, U.S.M.C.

Commander Amphibious Support Force (TF 52)--Rear Admiral W.H.P. Blandy.

Commander Attack Force (TF 53)--Rear Admiral H.W. Hill.

Commander Logistic Support Group (TG 50.8)--Rear Admiral D.B. Beary.

Commander Search and Reconnaissance Group (TG 509.5)--Commodore D. Ketcham.

Commander Service Squadron 10 (TG 50.9)--Commodore W.R. Cater.

The general plan of the operation was as follows:

Commence operation on D-minus-3-day (16 February), with a simultaneous fast carrier strike on the Tokyo area and bombardment of Iwo Jima by the Amphibious Support Force.

Fast carrier operations were planned to carry out a 2- to 3-day strike on the Tokyo area, the

1-1

third day being dependent upon the situation then existing, to give direct air support at Iwo Jima on D-day and D-plus-1-day, to strike the Kobe-Nagoya area on D-plus-4 and D-plus-5 days and to make a photographic strike on Okinawa on D-plus-9-day.

Bombardment of Iwo Jima to be continuous from D-minus-3-day on, augmented on D-day and as required thereafter, by some ships of Task Force 58.

Air support at the objective to be by CVE's from D-minus-3-day on, augmented as necessary on and after D-day by Task Force 58.

Landing to be made on D-day, 19 February, with provision for postponement of D-day in the event of weather unfavorable for carrier strikes or for landings.

Support by fleet units to continue as long as required.

The following assistance was to be provided by other forces:

Fourteenth Air Force conduct searches from China bases.

Pacific Ocean areas and Southwest Pacific area air forces conduct long range reconnaissance over the Western Pacific.

Twentieth Air Force support by attacks on the Empire.

Strategic Air Forces, Pacific Ocean areas, attack Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima commencing D-minus-20.

Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet, conduct reconnaissance and provide lifeguards.

The operation was conducted as scheduled, with the exception that a second strike on the Tokyo area was carried out in place of the scheduled Kobe-Nagoya strike. The decision to do this was made after bad weather on the first strike had prevented destruction of aircraft manufacturing facilities in the Tokyo area on the scale desired. It was felt more desirable to complete this planned destruction than to initiate a strike in a different area. Although unfavorable weather attended the second strike also, considerable damage was done to aircraft manufacturing plants and to airfields and installations in the two strikes, and they accomplished their primary purpose of preventing serious air interference with the amphibious operation at Iwo Jima.

The approach to Tokyo by Task Force 58 was made from Ulithi to the eastward of the Marianas and the Nanpo Shoto. Everything possible was done to guard against detection on the way in.

This involved radio deception, and scouting of the waters off Japan through which the approach was planned, in order to avoid, if possible, enemy search planes and picket vessels. This scouting was done by submarines, by PB4Y's of Fleet Air Wing One, and by B-29's of the Twenty-first Bomber Command. As a result of these efforts, assisted by bad weather off Tokyo, there was no detection.

This first major carrier strike against the Empire, which took place exactly 1 year after the initial carrier strike on Truk, was both helped and hampered by the foul weather on those 2 days. It was helped in that the low ceiling and rain assisted in preventing any Japanese attacks on our force. It was hampered in that considerable portions of the Tokyo area were at times so weathered out as to prevent our attacks on them. Our efforts were, because of this situation, more successful against enemy aircraft and airfield installations than they were against aircraft manufacturing plants. In spite of the bad weather, the results of the strike were of considerable value, both as a cover for Iwo Jima and as a preparation for Okinawa.

After withdrawing from the Tokyo area to the westward of the Nanpo Shoto, Task Force 58 refueled to the westward of Iwo Jima, sending the North Carolina, Washington, Birmingham, and Biloxi to take part in the bombardment in support of the landings on 19 February (D-day), and furnishing air support.

Ships from Task Force 58 which participated in the bombardment of Iwo Jima rejoined on the morning of 23 February, preparatory to fueling and making the second strike on the Tokyo area. Task Group 58.5, the night carrier group, remained behind to furnish night fighter protection for Iwo Jima. The approach to Tokyo was again made from the southeastward, but this time it was detected by a picket vessel the night before. As a result of very foul and unpredictable weather, the strike lasted only 1 day--25 February, and on account of the closed-in conditions in the target area the results of the strike there were not as great as had been hoped for. Hoping to find more favorable weather in another vicinity, an attempt was made to attack the Nagoya area on 26 February, but this was prevented by increasingly bad weather.

1-2

By this time the decision had been reached that the situation at Iwo Jima was such that Task Force 58, less Task Group 58.5 could be released from its support of the Iwo Jima operation, in order to prepare for the Okinawa operation. One task group proceeded direct to Ulithi, while the remaining three, after refueling, made a strike on Okinawa on 1 March, the primary purpose of which was to obtain additional photographs required for the Okinawa operation. On conclusion of this successful 1-day strike, these three task groups proceeded to Ulithi, where preparations were made for the coming Okinawa operation.

The withdrawal of four of the five task groups of Task Force 58 left available for air support at Iwo Jima the CVE's of Task Group 52.2 and Task Group 58.5. These ships were also required for the Okinawa operation. The date of their release depended upon the activation of an airfield on Iwo Jima and the establishment on it of sufficient day and night fighters to protect the area from Japanese air attacks, to furnish the air support required by the troops who were still fighting on the island, and to keep out of use the enemy airfield on Chichi Jima. The progress of the fighting on Iwo Jima posed a similar problem as affecting the release of the ships of the Joint Expeditionary Force which were furnishing support for the troops ashore. Fortunately, all forces were released in time to make the necessary preparations required for the Okinawa operation, although in the case of Task Group 58.5 only 2 days at Ulithi were available, which permitted no time for upkeep.

In addition to the air support furnished by Task Force 58 and the CVE's of Task group 52.2, the patrol planes of Fleet Air Wing One (TG 50.5) conducted searches by PB4Y's based on Tinian, to cover the areas between Iwo Jima and Japan. When the airfield on Iwo was ready, certain of these search sectors were extended by having the PB4Y's in those sectors stage through Iwo for additional gasoline on their return legs. Before this field was ready for use, patrol plane tenders anchored in the lee of Iwo Jima to service PBM's of Task Group 50.5 at such times as sea conditions would permit the operation of seaplanes. These PBM's were used for dumbo missions and for the extension of the more important search sectors toward Japan, commencing on 28 February. The tenders and PBM's were withdrawn when activation of the airfield ashore permitted their replacement by land planes and amphibians. The performance of the PBM's, with jet assisted take-off, in the bad sea conditions which normally existed around Iwo Jima, was a remarkable tribute to the ability of their pilots.

Enemy reaction to the Iwo Jima operation was very strong against the landings and the succeeding troop operations on shore. In spite of ample naval gunfire and air support, it was not until 16 March, after 26 days of hard fighting with heavy casualties, that all organized resistance ceased. The normal tactics evolved from previous Pacific operations were used and were proved to be sound against the strongest defense system the enemy was capable of erecting. It should be noted that these tactics were employed with skill and resolution by veteran troops. In view of the character of the defenses and the stubborn resistance encountered, it is fortunate that less seasoned or less resolute troops were not committed. The Fifth Amphibious Corps with its component Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine Divisions added many new pages to the records of heroic achievements in battle of the officers and men of the United States Marine Corps.

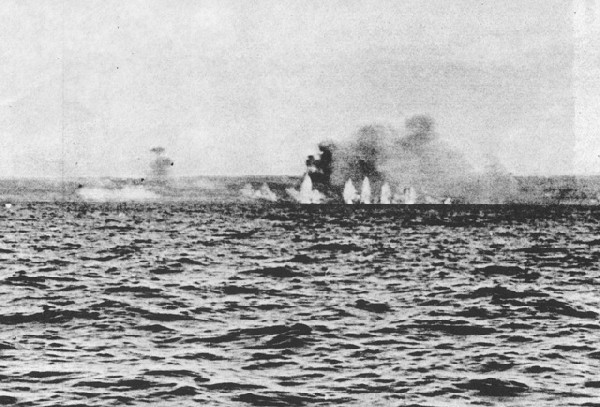

The enemy's air reaction to the Iwo Jima operation was not strong. No damage was inflicted on Task Force 58 while it was making the two strikes on the Tokyo area and the photographic strike on Okinawa. In the vicinity of Iwo Jima, however, a Japanese air attack of an estimated 50 planes arrived about dusk on the evening of 21 February and inflicted considerable damage. The Saratoga was hit by 4 suicide planes, which caused fires and extensive damage but did not affect the mobility of the ship. She proceeded to Pearl Harbor via Eniwetok. The Bismarck Sea (CVE) was hit on the stern by a suicide plane. As a result of fires and explosions that followed, she capsized and sank with heavy casualties. The Lunga Point (CVE), Keokuk, and LST 477 also suffered minor damage in this attack.

Enemy surface force reaction to the operation was lacking.

The Logistic Support Force, organized under a flag officer with the Detroit as his flagship, was given a trial and work-out during the Iwo Jima operation. The function of this force was to permit

1-3

ships of the Fleet--particularly those of the carrier task forces--to remain at sea over long periods by supplying underway as many of their logistic needs as possible. The real need for this was to come during the Okinawa operation, when the distances from rear bases were greater, the distance from the objective to Japan was less, the operation was expected to last longer, and the carrier task force had to remain at sea in support over a much longer period. To the services rendered during earlier operations by the fleet oilers and the transport CVE's there was added ammunition replenishment by ammunition ships. In addition, provisions were given to smaller types, critical items of supplies were brought out, and mail service was improved.

From: Commander Task Force 58 (Commander First Carrier Task Force)

This action report is submitted in broad form to provide a framework into which the more detailed reports of the task group commanders, ships' commanding officers and air groups may be fitted. The task force organization included 11 CV's, 5 CVL's, 8 BB's, 1 CB, 5 CA's, 11 CL's, 81 DD's, and over 1,200 airplanes.

During the period from 16 February to 1 March inclusive, planes from Task Force 58 flew a total of 5,514 sorties over the target including 185 dawn, dusk and night combat air patrol and night VT observer sorties over Iwo Jima. In addition a very large number of day combat air patrol, antisnooper patrol, search and other miscellaneous sorties were flown. During these operations aircraft from the Task Force actually dropped or launched at their targets 1,118.65 tons of bombs, 218 napalm bombs, 12 torpedoes, and 9,896 rockets. In addition, during the Tokyo strikes destroyers sank several enemy fishing and picket boats by gunfire. Cruisers and destroyers of the Force conducted a night bombardment of Okino Daito Island starting steady fires, and destroyers conducted a night bombardment of Parece Vela rocks with unobserved results. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers on detached duty from the force engaged in fire support missions at Iwo Jima.

Aircraft losses in combat from 16 February to 1 March, inclusive were 46 F6F, 1 F6F (N), 21 F4U, 1 F4U (P), 3 SB2C, 12 TBM, or a total of 84 aircraft of all types. Operational losses during the days of offensive air operations were 24 F6F, 7 F6F (N), 8 F4U, 4 SB2C, 13 TBM, 3 TBM (N) or a total of 59 aircraft of all types. Two of the VTN lost operationally were shot down by antiaircraft fire from friendly forces near Iwo Jima in bad weather during a daylight air raid alert.

During the same period, combat losses of flight personnel were 60 pilots and 21 aircrewmen. Operational losses were 8 pilots and 6 aircrewmen. In addition to rescuing personnel from the Force, destroyers assisted by planes rescued 8 survivors from a ditched B-29.

From: Commander Amphibious Forces, United States Pacific Fleet (Commander Joint Expeditionary Force)

The Joint Expeditionary Force (Task Force 51), a part of the Fifth Fleet, commenced active preparation for the operation in accordance with the provisions of CinCPOA Top Secret Dispatch, serial 092200 as of 9 October 1944, at which time certain units were made available to Commander Amphibious Forces, United States Pacific Fleet for planning and training.

The Joint Expeditionary Force, Task Force 51, as of target date, was composed of the following principal components:

- Amphibious Support Force (Task Force 52), Rear Admiral W.H.B. Blandy, U.S.N., commanding, comprising an air support control unit, support carrier group, mine group (Rear Admiral Sharp, U.S.N., commanding), underwater demolitions group, gunboat support group, mortar support group, and an RCM rocket support group, with the mission of pre-Dog-Day gunfire and air support, minesweeping, mooring buoy and net laying, beach reconnaissance and underwater demolitions.

- Attack Force (Task Force 53), Rear Admiral H.W. Hill, U.S.N., commanding and second in command of the Joint Expeditionary Force, comprising an air support control unit, two transport squadrons, tractor groups, LSM groups; control group, beach party group, and a pontoon barge, causeway and LCT group, with the mission of transporting and landing the expeditionary troops.

- Gunfire and Covering Force (Task Force 54) Rear Admiral B.J. Rodgers, U.S.N., commanding, comprising three battleship divisions, augmented on Dog-Day with two destroyer divisions

1-4

- Expeditionary Troops (Task Force 56), Lt. Gen. H.M. Smith, U.S.M.C., commanding, and consisting of all assault troops, plus certain assigned garrison troops, with the mission of executing the ground attack for the capture, occupation, and subsequent defense of the objective. Included was the Landing Force (Task Group 56.1), Maj. Gen. H. Schmidt, U.S.M.C., commanding, comprising the assault troops (Task Group 56.2), consisting of the V Amphibious Corps (4th MarDiv, Maj. Genl. C.B. Cates, U.S.M.C., commanding, and 5th MarDiv, Maj. Gen. K.E. Rockey, U.S.M.C., commanding), plus attached units; garrison force (task Group 10.16), commanded by Maj. Gen. J.E. Chaney, A.U.S., comprising units of the Army Air Force, Antiaircraft Artillery, Coast Artillery, with service and other units assigned; expeditionary troops reserve (Task group 56.3), Maj. Gen. G.B. Erskine, U.S.M.C., commanding, and comprising the Third Marine Division, plus attached units.

- Air Support Control Unit (Task Group 51.10) Capt. R.H. Whitehead, U.S.N., commanding, with the mission of support aircraft control, and air-sea rescue operations.

- Joint Expeditionary Force Reserve (Task Group 51.1), Commodore D.W. Loomis, U.S.N., commanding, consisting of one transport squadron, with the mission of transporting and landing the Expeditionary Troops Reserve when required.

- Transport Screen (Task Group 51.2), Captain Moosbrugger, U.S.N., commanding, comprising two destroyer squadrons and all escort vessels available at the objective and not employed for fire support and escort duty.

- Service and Salvage Group (Task Group 51.3), Captain Curtiss, commanding.

- Hydrographic Survey Group (Task Group 51.4), Commander Sanders, commanding.

- Defense and garrison Groups (Task groups 51.5, 51.6, 51.7, 51.8, and 51.9), comprising the first echelons of the Garrison Forces for Iwo Jima. Succeeding Garrison echelons, embarked by authorities other than CTF 51, assembled at Eniwetok and proceeded to the objective as ordered. On arrival, these elements operated under the Senior Officer Present Afloat, but were not integral parts of Task Force 51.

Summary of ships employed.--A total of 495 ships classified as to type in the table below were attached to, and employed by Task Force 51 during this operation. The list includes assault shipping and that of the Zero and First Garrison Echelons but does not include ships from other forces which operated temporarily under the Senior Officers Present Afloat, Iwo Jima.

Summary of ships employed

| Type | Number | Type | Number | Type | Number | Type | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGC | 4 | ATF | 2 | DD | 44 | OBB | 6 |

| AK | 2 | ATR | 2 | DE | 38 | PC | 7 |

| AKA | 16 | AV | 1 | DM | 8 | PCE | 1 |

| AKN | 2 | AVD | 2 | DMS | 6 | PCE(R) | 1 |

| AM | 16 | AVP | 1 | LCI | 58 | PCS | 10 |

| AN | 5 | BB | 2 | LCS(L) | 12 | SC | 12 |

| AP | 1 | CA | 9 | LCS(L)3 | 6 | YMS | 13 |

| APA | 43 | CB | 1 | XAP | 3 | Total ships | 495 |

| APD | 6 | XAK | 7 | LCT | 12 | ||

| ARB | 1 | CL | 9 | LSD | 3 | ||

| ARG | 1 | CM | 1 | LSM | 31 | ||

| ARL | 1 | CV | 1 | LSV | 1 | ||

| ARS | 3 | CVE | 1 | LST | 63 |

Summary of expeditionary troops engaged.--A statistical record of troops engaged in the operation appears in the table below. Navy personnel figures include only personnel assigned to duty ashore, including LCT and pontoon barge and causeway crews, boat pools, and beach parties.

Summary of Expeditionary troops employed

| Assault troops | Garrison troops | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army | Marine | Army | Marine | Navy | ||

| Landing force | 570 | 70,647 | 3,927 | 75,144 | ||

| Garrison force | 23,830 | 492 | 11,842 | 36,164 | ||

|

||||||

| Net total troops employed | 570 | 70,647 | 23,830 | 492 | 15,769 | 111,308 |

In furtherance of the general objective of the United States Pacific Fleet in the Western Pacific, the Joint Expeditionary Force (Amphibious Forces, U.S. Pacific Fleet) was, as a part of the Fifth Fleet, assigned the mission for the capture, occupation and defense of Iwo Jima. The Fifth Fleet covered the amphibious part of

1-5

the operation by attacks on Japan and local cover, and directly supported it with aircraft and gunfire bombardment in support of troops, and by providing night fighter cover. The Fifth Fleet was assisted by other forces under the control of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean area, the Commander Southwest Pacific area, and the Twentieth Bomber Command. The strategy employed in this operation included these salient points:

- Bases in the Hawaiian Islands and the Marianas served to lift and mount the Expeditionary Force.

- Bases in the Marshalls and Marianas functioned as regulating stations, provided the protection for sea and air lines of communication, and facilities for staging.

- Bases in the Marianas enabled the assembly of the combined task Force prior to its final movement to the objective.

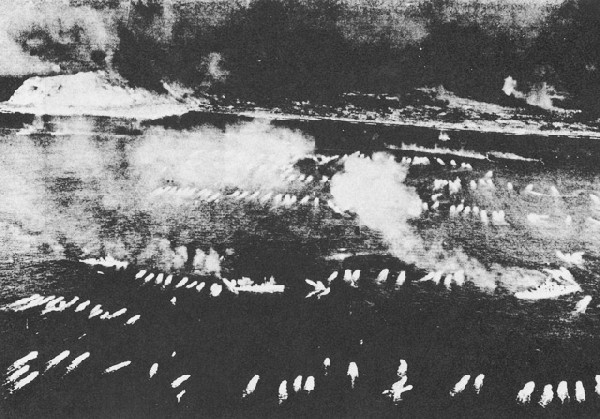

- The Amphibious Support Force and gunfire and Covering Force struck Iwo Jima for 3 days prior to Dog-Day with naval gunfire and air bombardment in order to soften up the enemy defenses, destroy his fortifications, destroy his aircraft, and to neutralize his airfields.

- The Fast Carrier Force struck the Tokyo area and the Nagoya-Kobe area simultaneously with the pre-Dog Day bombardment of Iwo Jima by our surface vessels for the purpose of destroying enemy aircraft and air facilities which might interfere with the Iwo Jima operation. Later this force furnished air cover and direct support at Iwo Jima.

- Shore-based aircraft operating in the Central Pacific, Southwest Pacific, and from bases in China and India, supported the operation through air reconnaissance, antisubmarine searches, offensive screens, air-sea rescue missions, and photo reconnaissance.

- The Strategic Air Force, Pacific Ocean areas, operating land aircraft from bases in the Marianas, struck military installations in the Nanpo-Shoto for a period of several months prior to Dog-Day with heavy concentrations on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima for the purpose of softening up enemy defenses, destroying his aircraft and shipping, and neutralizing his airfields. It further furnished photo reconnaissance of the Nanpo-Shoto and engaged in air and sea rescue.

- The Twentieth Air Force employed the Twentieth Bomber Command by strikes on Kyushu both preliminary to and simultaneously with the carrier strikes on the Tokyo area. The Twenty-first bomber Command increased its bombing tempo in the Tokyo area prior to the carrier strikes, coordinated its strikes with those of the carrier groups and covered the carrier retirement by strikes in the Tokyo area.

- The Amphibious Support Force and Gunfire and Covering Force supported the Landing force with reinforcing fires and air bombardment on the beaches, and with deep supporting fires inland during the assault and occupation phase of the Operation.

- The Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet, provided intelligence relative to movements of enemy Naval Units, through reconnaissance off enemy bases and routes of approach, and attacks on enemy shipping. It also engaged in lifeguard service, accomplished photo missions, and furnished weather reports.

- The Marianas and Hawaiian bases provided a means for the rehabilitation of the assault troops following their evacuation from the objective.

The Amphibious Support Force (TF 52) and the Gunfire and Covering Force (TF 54) arrived at the objective at Dog-minus-Three-Day. From this time until Dog-Day minesweeping of all mineable waters was completed; and a reconnaissance of both the preferred and alternate landing beaches was conducted by the underwater demolition teams. TF 54 delivered destructive fires against selected enemy positions, engaged in counterbattery fire, and covered the minesweeping and UDT operations.

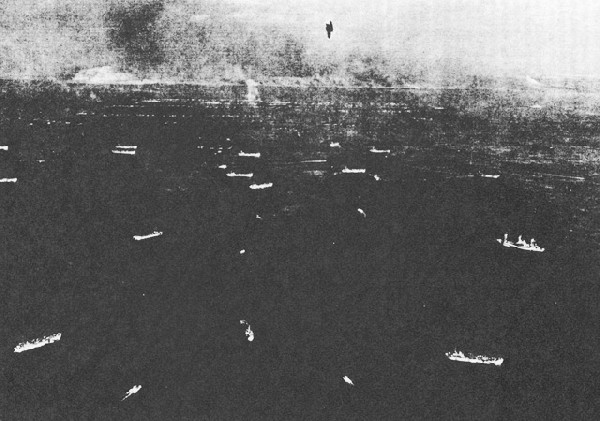

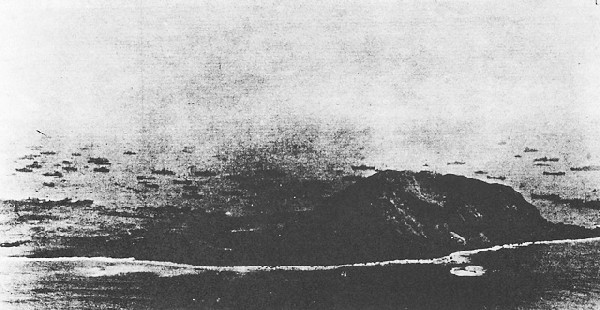

The Attack Force (TF 53) arrived in the transport areas off the eastern beaches prior to daylight on Dog-day 19 February and took position for debarking the Landing Force (TG 56.1). At 0600 (K) Dog-Day; the Amphibious Support Force (TF 52) passed to direct command of CTF 51, who then also assumed the title of CTF 52. Following intensive air and naval bombardments, the Fourth and Fifth Marine divisions landed on Iwo Jima at How-Hour, 0900 (K), as scheduled. The initial boat waves met only slight opposition. Later in the day, however, the beach areas were subjected to heavy enemy artillery and mortar fire. Some fire was directed into the beach approaches and the LST Areas, registering a few hits. The natural features of

1-6

terrain plus an exploitation of camouflage rendered almost perfect concealment to enemy gun emplacements. Many could not be located, and our troops and boats had to "stand and take it."

On Dog-day air strength was concentrated for the Pre-How-Hour and How-Hour strikes. Aircraft were supplied by the CVE's of Task Group 52.2 augmented by planes from Fast Carrier Task Groups 58.2, 58.3, and 58.5. A small force of Army B-24's was scheduled to assist by arrived late and could be used only in part. The large number of carrier planes was organized to create the maximum destructive effect with bombardment at How-minus-50-minutes. They then harassed and neutralized exposed enemy gunners at How-Hour in order to protect the final movement of the assault waves to the beach.

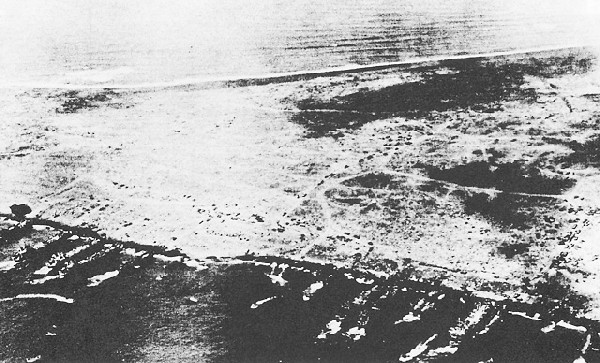

The adverse beach conditions soon became apparent. With a steep gradient such as this, the surf breaks directly upon the beach. It was impossible with the heavy swells to prevent the landing craft from broaching. With each wave, boats were picked up bodily and thrown broadside to the beach where succeeding waves swamped and wrecked them. Losses had to be accepted until the beachhead was secured, and until LST's, LSM's and LCT's could be employed. The resultant accumulation of wreckage piled progressively higher, and extended seaward into the beach approaches to form underwater obstacles which damaged propellers and even gutted a few of the landing ships.

Although from seaward the beach appeared hard-packed, it was soon discovered that volcanic ash has no cohesive consistency. Wheeled vehicles bogged to their frames. A few tanks bogged in the surf and were swamped. Even tracked vehicles moved with difficulty. The first terrace has a 40 percent grade which proved insurmountable for some amphibious tractors. This was the problem that faced the boat crews and troops, and despite it the attack moved forward. A trail of wreckage marked the way.

LST's and LSM's were sent to the beaches as soon as the beachhead was secured. These, too, had difficulty to keep from broaching. Several failed when anchors did not hold. Tugs were in constant attendance to tow them clear. Unloading continued day and night with the beach parties working "around the clock." Ships of the Gunfire and Covering Force delivered call fire missions during the day and starshell illumination and harassing fires throughout the night. As ammunition ran low in the destroyers of TF 54, rotation was made with destroyers of the screen. The Gunboat Support Groups were stationed close to shore in sectors around the northern end of the island and delivered night harassing and destructive fires (including mortars and rockets) against enemy positions. Their presence also deterred the enemy from shore to shore overwater movements. The gunboats were regularly taken under fire by enemy guns. None was hit, and destroyers which supported them were enabled to silence some of the enemy batteries.

Difficulties of unloading and replenishment persisted--not only on the beaches but also in the transports. The weather closed down at 1500 (K), Dog-plus-One-Day, with strong winds and heavy swells curtailing air operations. Throughout this period unloading and replenishment had to be carried out underway. This was difficult for unloading since the distance to the beach and the urgent need for speed had constantly to be borne in mind. Restricted movement resulted in many operational casualties to the ships--which of necessity had to be accepted.

To alleviate the surf problem on the beaches, and to permit continued employment of boats, it was decided to launch the pontoon causeways as soon as practicable. However, they could not be employed successfully. All attempts to anchor the seaward ends of the barges were unsuccessful. Like the boats, they also broached, were damaged and sank, or ra adrift; and in every status became a menace to navigation. Decision was then made to launch the LCT's; to employ these craft plus LSM's and LST's only for unloading; and to close the beaches to craft smaller than LST's. The only exception was the employment of amphibious vehicles, which worked very successfully, for the evacuation of casualties.

Vessels not engaged in unloading retired each night and returned to the transport area after daylight. Task groups not scheduled to unload remained in operating areas, usually to the southeast, until ordered forward. The limited size of the objective area and the large number of ships involved required careful scheduling of times of arrival, and demanded arrival after, rather than at, daybreak.

1-7

The necessary dense concentration of the assault shipping in the comparatively narrow area off the assault beaches is probably partially responsible for the large number of collisions which occurred in this operation. The beaches were narrow by reason of the physical characteristics of the island. The number of troops carried involved a large amount of shipping. Sea conditions made boating difficult, and it was imperative that the distance to the beaches be kept at a minimum. In addition the gunnery problem demanded that certain fire support ships position themselves along the edges of the transport area in order to properly deliver the fire required. This added to the congestion. Other causes of collisions were inexperienced personnel and unfavorable weather.

Collisions occurred between landing craft and landing ships, between landing ships and gunboats, between fire support ships and transports, and between ships of the same types. These are explained in detail in another section of this report.

The UDT's and beach parties cleared the beaches of accumulated wreckage. The Service and Salvage Group cleared the beach approaches, salvaged boats and pontoons, and effected emergency repairs to damaged ships. These were herculean tasks and proceeded apace with the unloading, the replenishment, the evacuation of casualties, and the rendering of supporting fires so that the assault might continue.

Throughout the operation aircraft were maintained on station for direct support missions on targets requested by the troops or as indicated desirable by air observation or photographic intelligence. Air Spot for naval gunfire was provided by cruiser and battleship seaplanes and by fighters from a special spotting squadron based on Wake Island. Tactical observers were maintained in the air continuously, aerial photographers were flown and propaganda leaflets were dropped. Combat air patrol was maintained over Iwo on a 24-hour-a-day basis with special emphasis on the dawn and dusk periods. Continuous day and night air antisubmarine protection was given to the objective by carrier TBM planes.

The largest and most destructive enemy air attack was made by an estimated 50 Betty's and Zeke's, which attacked carriers and amphibious ships at Iwo from 1640 to 2000 on Dog-plus-Two (21 February). Enemy planes were divided into small groups for their attacks. Saratoga, Bismarck Sea, Lunga Point, Keokuk, and LST 477 were hit by suiciders. Saratoga suffered three hits by suicide planes on the initial attack and one hit on attacks slightly later. She was badly damaged and forced to return for navy yard repairs. Her losses were 25 dead, 57 wounded. Bismarck Sea was struck by a suicide plane aft. The initial explosion was followed by fire and later by explosions of her torpedoes which caused her to sink, 100 officers and 513 men surviving the sinking out of a total complement of 124 officers and 836 men. One enemy plane was shot down by Saratoga fighters and 15 by antiaircraft fire from ships. Of the 15 Saratoga planes which were airborne when she was hit, 5 landed safely on her, 4 landed on CVE's, 4 landed in the water but pilots were rescued, and only 2 are missing. All Bismarck Sea planes were on board at the time of sinking and were lost.

The fast carriers less Enterprise departed on Dog-plus-three for their second strike on Tokyo. Thereafter all air activities were furnished by the CVE's plus Enterprise, with two minor exceptions: On 25 and 27 February nine Army B-24's made a bombing attack on Northern Iwo. Enterprise furnished dusk and night fighters, neutralized Chichi and Haha Jima with dawn and dusk sweeps and made searches. The CVE's provided all direct support for the troops, the day CAP, day and night ASP, plus special flights.

To augment the Fourth and Fifth Marine Divisions, two RCT's of the Third Marine Division (RCT 21 and 9) were landed on Dog-plus-Two and-Five respectively. The commanding general, Third Marine Division was assigned a zone of action in the center of the line between the Fourth and Fifth Marine Divisions.

During this period Dog-plus-One to Dog-plus-Five an unprecedented number of call fire missions were delivered. This was due to the restrictive effect of the weather upon air support, and to the enemy's strong resistance. Replenishment and unloading were slow. Whereas the slowdown in unloading permitted the beach parties to improve beach conditions, the ammunition situation both afloat and ashore became critical. On Dog-plus-Four it was difficult to find ships with sufficient ammunition to deliver the call fires

1-8

requested. Fortunately on the night of Dog-plus-Four the weather cleared, and Dog-plus-Five found wind and sea greatly moderated with visibility and ceiling unlimited. Marked progress in the beach clearance program was now evident, and unloading and ammunition replenishment were accelerated.

Special seaplane service for the purpose of carrying urgent news matter to the CinCPac Guam commenced Dog-Day, and except when prevented by bad weather, was continued throughout the operation until the captured airfield on Iwo was made serviceable. Although seaplane tenders arrived on Dog-plus-One-Day enemy activity in the vicinity of Mount Suribachi prevented the establishment of the seaplane base off the southeastern shore until Dog-plus-Five-Day. Seaplane mooring buoys were laid and the tenders moved to inshore anchorages. The first search seaplanes were delayed in arriving from Saipan until Dog-plus-Eight due to bad weather. Searches were commenced the following day. A total of 15 search PBM's and 3 dumbo PB2Y Seacats were operated from the seaplane base. All were equipped with jet-assisted take-off devices to enable them to get off rough water more rapidly and with a greater load. On Dog-plus-Fifteen (6 March) PB4Y search planes commenced employing the airfield ion Iwo as a staging base to increase their radius from Tinian to 1,200 miles. At this time seaplane activities were curtailed and the search seaplanes returned to Saipan. On 8 March 3 PBY5A Landcats arrived at Iwo and took over dumbo operations. The dumbo seaplanes then returned to Saipan as did the tenders. The seaplane base was decommissioned on 8 March.

On Dog-plus-Five (24 February) the Hydrographic Survey Group (TG 51.4) completed a survey for locating mooring buoys and nets. Since Dog-Day it had been noted that, regardless of weather, so long as easterly winds prevailed the resultant swell continued to make conditions difficult on the eastern beaches. The front lines had advanced sufficiently to indicate the feasibility of a shift to the western beaches. Consequently, on Dog-plus-Six, a survey of PURPLE and BROWN beaches was commenced. It was found that these beaches would be excellent for boats, but that the water was too shallow for craft larger than an LSM. The situation indicated that these beaches could best be used initially for unloading ammunition; and plans for creating exits ashore from these beaches proceeded accordingly. On Dog-plus-Ten (1 March) Columbia Victory proceeded to take station for unloading off the western beaches. No sooner did she approach this area than she was taken under fire by enemy coast defense guns in the northwestern end of the island. After having been straddled several times, and having received superficial damage with one man wounded from flying fragments, she withdrew. Unloading to the western beaches was therefore postponed one day until the enemy guns could be silenced. Off the northern end of the island Terry and Colhoun were hit by enemy coast defense guns on 1 March. These guns also were silenced.

The first United States aircraft to commence operations from Iwo were OY-1 artillery spotting planes on 27 February. Twenty OY aircraft were brought to Iwo, 2 each in 7 CVE's and 6 in LST 776 which is equipped with the Brodie device. Two were lost in the sinking of Bismarck Sea and 1 was lost in launching from the Brodie LST. The remaining 17 were in operation from Iwo by 1 March, and flew both day and night missions spotting for artillery.

Air delivery of supplies by parachute was made from three Saipan-based R5C's on 28 February. The next day mail for the troops on shore was dropped by parachute from an R5C airplane. Parachute delivery continued until transport planes commenced operations at the field on 2 March. Air supply and air evacuation were conducted on a large scale from then on.

On 3 March the situation from a naval standpoint became relatively quiet, and continued so throughout the remainder of the operation. Good weather had remained at the objective since 24 February. The enemy had been forced into the narrow northern sectors of the island. Although enemy artillery, mortar and some rocket fire continued to land in the beach areas, this fire was sporadic and registered few hits. Unloading and evacuation progressed favorably over both eastern and western beaches and by 3 March all the assault shipping including the defense group (TG 51.5) and the Joint Expeditionary Force Reserve (TG 51.1) had been unloaded and retired to rear areas. Garrison Group Zero (TG 51.6) arrived in the transport areas on 2 March and

1-9

commenced unloading. Garrison Group One (TG 51.7) was en route.

On 4 March Sumner (AGS 5) and YP 42 arrived to commence a general hydrographic survey of Iwo Jima. Meanwhile the operation for laying the antisubmarine nets was suspended. Volcanic ash apparently covers the ocean's bottom throughout this area, forming such poor holding ground as to create doubt that the net buoy anchors would hold. A further survey was indicated, and the net officer of CTF 94 was called forward for consultation. As a result of further survey, it was determined that the net-laying plan was feasible; and the operation was commenced on 11 March.

As soon as garrison aircraft could be accommodated at south field Iwo they flew in from Saipan. The first were Army P51 day fighters and P61 night fighters which arrived on 6 March, and took over local day and night CAP. Two days later more P51's and a squadron of VMTB arrived. The VMTB commenced flying day and night ASP on 10 March. By 11 March all air activity at Iwo was provided by shore-based aircraft operating from the captured field.

By 7 March enemy-occupied territory had become so restricted that naval gunfire support could be provided only to a very limited extent. Therefore the major portion of TF 54 was ordered to Ulithi for upkeep. ComCruDiv 5 in Salt Lake City with Tuscaloosa and destroyers present remained as Gunfire and Covering Force until 12 March when they also retired to Ulithi. Carriers departed from Iwo for Ulithi in three groups. On 8 March Makin Island, Lunga Point, Rudyerd Bay, Natoma Bay, and Petrof Bay departed. On 9 March Enterprise departed. On 11 March the remaining CVE's departed from Iwo Jima and all carrier support was withdrawn.

On 9 March Commander Joint Expeditionary Force (CTF 51) ordered TF 51 dissolved, and turned over command of the operation to CTF 53 who thereafter assumed title CTG 51.21 as Sopa Iwo Jima. The Commander Landing Force (CTG 56.1) thereafter assumed title CTG 51.27, while the island commander retained his designation CTG 10.16.

Throughout the operation, commencing Dog-plus-One (20 February) hospital ships Samaritan and Solace made shuttle trips between Iwo Jima and Saipan or Guam for the evacuation of serious personnel casualties. These trips were augmented by employment of Pinckney (APH-2) and Bountiful, with one round trip each. In addition four hospital LST's (LST(H) 929, 930, 931, 1033) were in position off the assault beaches for the immediate reception of casualties from Dog-Day through Dog-plus-Nine-Day (28 February). These LST(H)'s acted as "Field Hospitals", and after necessary surgery and treatment, casualties were transferred to retiring transports. The more serious cases were transferred to the hospital ships for further treatment. Air evacuation was inaugurated after 2 March when the airfield was opened to transport planes.

Numerous submarine contacts with several sightings were made during this operation. In every case hunter-killer groups were ordered to the point of contact and persistent search maintained, until positive evaluation could be made. Evidence indicates that several "kills" were obtained.

On 8 March the wind shifted into the northwest and caused heavy swells on the western beaches. Unloading in this area was interrupted, and ships moved to the eastern side of the island. Garrison Group One arrived and commenced unloading. The next day Garrison Group Zero completed unloading and retired to rear areas. By 14 March Garrison Group One had completed unloading, and garrison Group Two had arrived to commence unloading. Meanwhile the net laying operation, which was initiated on 11 March, proceeded favorably and on 19 March 4,000 feet of net had been installed. Unloading over both eastern and western beaches continued intermittently, dependent upon the weather and surf conditions, throughout the remainder of the operation.

The assault continued favorably, registering only small daily gains, as the enemy became more and more compressed into the northern portion of the island. Naval gunfire support was limited to destroyer call fires and night harassing assignments. By 13 March enemy artillery and mortar fire had ceased, and resistance resolved into small arms and hand-to-hand fighting.

The airfields on Iwo Jima commenced "paying dividends" soon after being placed in operation. In addition to providing safe landings for many carrier planes in difficulty, the South field proved a haven to many B-29's. On 17 March 16 B-29's

1-10

returning from a strike against the Empire utilized Iwo for emergency landings. Two days later six of this type aircraft landed for refueling or repairs. Central airfield was placed in operation on 16 March.

It has been noted that enemy picket boats stationed in the approach areas to the Empire were providing advance warning of impending strikes against Japan. TF 58, in its strikes against Tokyo during this operation, had destroyed several of these picket boats. B-29's reported sighting several on patrol north of Chichi Jima. Sopa Iwo Jima (CTG 51.21) therefore, on 13 March, formed TU 51.24.1 composed of Dortch and Cotten, and ordered a surface sweep of the area between latitude 30-00 N. and 31-00 N. and longitude 144-00 E. and 145-00 E. To be made during 14 and 15 March. One enemy vessel, identified as Yatsue O Maru or Fiji Maru was contacted during this search and destroyed.

The National Ensign was raised officially on Iwo Jima at 0930 (K) 14 March 1945. All organized resistance was declared as having ceased at 1800 (K) 16 March. The Fourth Marine Division commenced reembarkation the following day, with the Fifth division the day after. Division headquarters were closed on Iwo Jima on 19 March and 20 March respectively, and on 20 March the Fourth Marine Division departed for Maui for rehabilitation. On 20 March the Garrison Force (147th Inf. Reg.) arrived at Iwo Jima. Meanwhile combat requirements in the "mopping up" operation delayed reembarkation of the Fifth MarDiv until 25 March by which time all enemy pockets of resistance were eliminated. The Third MarDiv also continued "mopping up" operations. On 26 March Iwo Jima was turned over to the Island Commander and the Commander Forward Area. The Fifth MarDiv and Corps Troops completed reembarkation on 28 March and departed for rehabilitation in the Hawaiian area. The following day the Third MarDiv departed for rehabilitation at Guam.

From D-Minus-3 (16 February) to D-Day (19 February)

From: Commander Amphibious Group ONE, Commander Amphibious Support Force

The function of this command during subject period was to exercise general supervision over, and coordinate, all activities at the objective prior to the arrival of the landing and assault elements of the Joint Expeditionary Force on Dog-Day (19 February). The forces participating in these prelanding activities of Task Force 52 were:

- The Gunfire and Covering Force, Task Force 54, under command of Rear Admiral B.J. Rodgers, U.S.N. (Commander Amphibious Group Eleven), consisting of 6 OBB's, 4 CA's, 1 CL, 15 DD's, 1 DM, and 1 AVD.

- The Support Carrier Group, Task Group 52.2, under command of Rear Admiral C.T. DUrgin, U.S.N. (Commander Escort Carriers, U.S. Pacific Fleet), consisting of 8 CVE's, 5 DD's, and 9 DE's.

- The Mine Group, Task Group 52.3, under command of Rear Admiral A. Sharp, U.S.N. (Commander Minecraft, U.S. Pacific Fleet), consisting of 7 Sweep Units comprising 43 minecraft plus 8 LCP(R)'s rigged for shallow water minesweeping.

- The Underwater Demolition Group, Task Group 52.4, under command of Capt. B.H. Hanlon, U.S.N. (Commander Underwater Demolition Teams, U.S. Pacific Fleet), consisting of 6 APD's carrying UDT's Nos. 12, 13, 14, 15.

- Gunboat Support Units One and Two, Task Units 52.5.1 and 52.5.2, under command of Commander M.J. Malanaphy, U.S.N. (Commander LCI Flotilla Three), consisting of 1 LCI(L) and 12 LCI(G)'s.

- Land-based heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force, Pacific Ocean Areas, Task Force 93, delivered air strikes under the control of Commander Air Support Control Unit, Task group 52.10, Capt. E.C. Parker, U.S.N., embarked in the flagship of Commander Task Force 52, when weather permitted.

The mission of forces under this command was to effect the maximum possible destruction of enemy forces and defenses of Iwo Jima by aircraft and surface ship bombardment, minesweeping, and underwater demolition, during the period D-minus-3 to D-minus-1, inclusive, in order to facilitate its capture.

The general plan of operations at Iwo Jima for 16 February consisted, briefly, of sweeping adjacent waters to within approximately 6,000 yards of the shore, gunfire at long (above 12,000 yards) and medium (from 6,000 to 12,000 yards) ranges

1-11

with air spot for destruction of defenses and silencing of enemy batteries, air strikes by support carrier aircraft and land-based heavy bombers of TF 93, examination of beaches from the air by special hydrographic observers, aircraft photo missions in late morning and afternoon, installation of a navigational light on Higashi Iwa, a small rocky islet about 3,000 yards to the eastward of Iwo Jima, and early morning and late afternoon fighter sweeps against Chichi Jima to destroy planes and ships or boats which might interfere with the operation. Fire support ships were to follow minesweeping units in toward the island and then work in their assigned sectors inside a screen of destroyers and APD's which enclosed the island area. APD's were to conduct visual reconnaissance of beaches, but not to approach closer than 3,000 yards. This plan was followed, except that low ceiling and intermittent showers prevented the photo mission, the morning strike against Chichi Jima, the strike of land-based bombers, and severely handicapped the spotting planes. CTF 52, in order to prevent waste of ammunition, directed ships to fire only when efficient air spot was available. It was not possible to follow the planned firing schedules, and instead each ship fired in its assigned area of responsibility whenever weather permitted. Two enemy luggers were discovered early in the morning by support aircraft about 30 miles west of Suribachi Mountain. They were attacked and left burning and in a sinking condition, with crews abandoning ship. In the early afternoon a Pensacola spotting plane reported shooting down a Zeke which had apparently taken off from Iwo Jima. Three Betty's were strafed and probably destroyed on the ground. A battery which opened fire on minesweepers from northern flank of eastern beach was quickly silenced by fire support ships. None of our ships was hit. One fighter plane and pilot became lost in thick weather and did not return. One plane was an operational loss. One fighter plane was shot down by enemy AA but the pilot was recovered uninjured. One New York spotting plane was damaged on catapulting, and sank after personnel were removed. Results of minesweeping were negative, but one old mine adrift was sighted and sunk. Excellent reports were received from the air hydrographic observer indicating that beaches and surf conditions would permit landings by any type of landing craft. He could see no evidence of underwater defenses. Lack of photographs and the paucity of observed results by ships and aircraft prevented accurate assessment of damage to enemy installations. It was estimated, however, that the comparatively small amount of firing permitted by the intermittent thick weather had inflicted little damage on major defenses. Pilots reported enemy heavy AA gunfire not particularly intense or effective, and fire of Automatic AA intense but generally inaccurate.

At sunset all ships commenced night deployment away from the island, except for four destroyers which were designated to remain and provide harassing fire and illumination, interdict the use and repair of airfields, and prevent escape or reinforcement of the garrison. CTF 52 in Estes, screened by 4 AM's, after following the fire support units away from the island during dusk, returned to the vicinity of the island to supervise night operations.

Operations planned for 17 February consisted in general of morning and evening fighter sweeps against Chichi Jima; close range destructive fire against eastern beach defenses during which minesweeping up to about 150 yards from the eastern shore would be covered by the heavy ships; UDT reconnaissance of eastern beaches in the late morning closely supported by heavy ships, 7 destroyers and 7 LCI(G)'s; strikes by land-based bombers at 1330; close range destructive fire on western beaches; minesweeping off western beaches and UDT reconnaissance of these beaches supported as in the morning; minesweeping to within about 2,000 yards of the northern and northeastern shore; hydrographic observation of beach conditions from the air, photo missions, and night operations at the objective as on 16 February. At 0124 (K) ComDesDiv 111 in Newcomb, with Halligan, was directed to proceed to point (Lat. 26°00' N, Long. 141°50' E.) and to act as radar pickets and provide life guard services for air strikes against Chichi Jima. At 0641 (K) Halligan was attacked by three Betty's when 24 miles, bearing 355°, from Suribachi Mountain. She drove off the attackers, shooting down one Betty. Fire support ships arrived on station and commenced the scheduled bombardment promptly at 0700 (K). Mine Unit Two, in company with Gunboat Support Units One and Two, arrived at 0700 (K). Gunboat support units reported to

1-12

CTG 52.4 and Sweep Units 5 and 6 to CTG 52.3. A special air strike group of 12 VF's departed for Chichi Jima at 0735 (K). The first support air strike group reported on station at 0715 (K). During the day many air strikes were launched against the objective through meager to intense heavy and light antiaircraft fire. Photographic missions were completed, but the morning verticals were poor, preventing accurate damage assessment. The fire support ships were ordered to close the eastern beaches at 0803 (K) for close destructive bombardment. Under cover of this fire, and supported by two destroyers, Sweep Units 5 and 6 proceeded with operations along the eastern shore. APD's with UDT's embarked, destroyers and LCI(G)'s began assembling off the eastern beaches about 0930 for execution of the UDT reconnaissance. At 0938 the Pensacola, off the northeastern shore, was observed to be under fire by apparently quite heavy caliber guns as some splashes appeared to be almost as high as her foremast. She sustained extensive damage and many casualties. A plane was set on fire. The ship continued to fire as she withdrew to extinguish the fires and repair damage. She continued to carry out her mission, ceasing fire from time to time while casualties were being operated on and given blood transfusions. CTG 52.3 requested additional support for Sweep Unit 4 working off the northeastern shore, and Vicksburg was ordered to provide it. By 1048 (K) all units were in position to commence the UDT reconnaissance set for 1100 (K). The last of the minesweepers was completing the sweep off the eastern beaches, these small ships having gallantly passed close along the eastern shore in precise formation, firing as they went, without deviation from their prescribed tracks although under occasional enemy fire. The UDT reconnaissance commenced exactly on schedule. As the LCI(G)'s moved in toward the beach, enemy fire began to concentrate on them. By 1105 (K), when they reached a point 1,000 yards off shore, enemy fire was intense from both medium and minor caliber weapons on the flanks and minor caliber along the beaches. The personnel of these little gunboats displayed magnificent courage as they returned fire with everything they had and refused to move out until they were forced to do so by matériel and personnel casualties. Even then, after undergoing terrific punishment, some returned to their stations amid a hail of fire, until again heavily hit. Relief LCI(G)'s replaced damaged ships without hesitation. Between 1100 (K) and 1145(K) all 12 of the LCI(G)'s were hit. LCI 474 ultimately capsized after the crew had been removed, and was ordered sunk Intensive fire from destroyers and fire support ships, and a smoke screen laid by white phosphorous projectiles, were used to cover this operation, Fire support ships took on board casualties from the LCI(G)'s as they withdrew, and CTG 52.3 in Terror most promptly and efficiently initiated emergency repairs for serious hull damage, as well as assisting in care of the wounded. At 1121 (K) Leutze was hit, the commanding officer receiving serious injuries, requiring his later transfer to Estes, but no extensive damage was sustained by the ship. By 1220 (K) all swimmers of the UDT's but one had been recovered, and the APD's and supporting destroyers moved out of the area. The reconnaissance had been accomplished. It disclosed no underwater or beach obstructions and no mine fields, though one J13 "reef mine" was reported in 8 feet of water off the north flank of Red 2 Beach. Beach and surf conditions were found to be good for landing.

Early in the afternoon heavy fire support ships were ordered to close the western beaches and commence destructive short-range fire. At 1354 (K) three squadrons of land-based bombers of Task Force 93 commenced bombing runs on the objective. The first squadron encountered little large caliber AA fire, but this fire increased in intensity and accuracy as the second and third squadrons commenced their runs. It was learned later that one plane received major damage, and a few others minor damage, but that all were able to return to base. The bombing was conducted from about 5,000 feet altitude, and appeared to be most precise. Under cover of close-in fire support ships with two destroyers in direct support, Sweep Units 5 and 6 swept the area close to the western beaches, without drawing more than sporadic fire from the island. UDT reconnaissance of the western beaches was commenced at 1615 (K). The support was modified in that no LCI(G)'s were used and the destroyers were ordered to close from 3,000 yards to 2,000 yards. A smoke screen by aircraft was ordered but the smoke planes had difficulty in complying,

1-13

as the screen was not laid until 20 minutes after the order, and was not placed where ordered. The operation was partially screened by white phosphorus projectiles laid on the northern and southern flanks, and behind the beaches. The UDT's accomplished the reconnaissance successfully. One mine was found and a delay charge placed to destroy it. Minefields or underwater obstacles were determined to be nonexistent, and beaches and surf conditions were found to be suitable for landing.

At 1734 (K), Howard reported rescuing three men from a crashed TBF. Night deployment commenced about 1830 (K). Edwards, Twiggs, and Stembel were designated to remain at the objective to execute night harassing fire, interdiction of airfields, prevent escape or reinforcement of the garrison, and to maintain careful surveillance of the beaches to ensure that the enemy did not work on them. Mullany, APD's of TG 52.4 and Sweep Unit 4 remained with Estes in the vicinity of the objective, as did the Gunboat Support Units 1 and 2. Shortly after dark Twiggs shot down one enemy plane near the island. At 2321 (K) Waters and Bull were despatched with beach charts and personnel from the UDT's for distribution and dissemination of information on the beach reconnaissances to CTF 51, CTF 53, and designated elements of the Attack Force. Strikes on Chichi Jima resulted in damage to about 18 small craft and an ammunition barge blown up. At Haha Jima about 15 small and 1 medium-sized craft were damaged. It was estimated, and examination of the afternoon photographs confirmed, that the greater part of major known defensive installations still remained undamaged. However, heavily casemated batteries at the northern base of Suribachi (already on map) and on the right flank of the astern beaches (3 of the 4 guns not on map) had been definitely located. Orders were issued changing schedules of fire for 18 February to provide for heavy concentration of destructive fire from short range on the blockhouses, pillboxes, etc., of the eastern beach area, and defenses behind it on each flank. For knocking out the heavy flanking batteries a cross fire by Idaho and Tennessee was directed. It was felt that unless this was done, the success of the landing itself would be seriously jeopardized, even though it was realized that guns and mortars in other areas would probably give trouble after the landing. Fire support ships were advised of the entire situation, and directed to make every effort to obtain the greatest possible effect from each remaining round of ammunition and minute of time.

At 0308 (K) on 18 February Mullany was sent to rendezvous with Lunga Point with photographs for delivery by plane that morning to CTF 51 and various elements of the Attack Force. Minesweeping commenced on schedule. Fire support ships were on station at 0700 (K) and off the eastern beaches delivered almost continuous fire from 0700 (K) to 1830 (K) at ranges of from 1,800 to 3,000 yards from the shore. Other ships fired at targets in other areas throughout the same period. Texas, assisted by two destroyers, also covered uncompleted minesweeping operations off the northern shore. During the afternoon a Texas spotting plane recovered a downed pilot, uninjured, from 135 miles at sea. He had been sighted by a B29 of the Twenty-first Bomber Command.

Night deployments were commenced at sunset, except that 5 destroyers were assigned to usual night operations at the objective, with special instructions to ensure that no work by the enemy was accomplished on the beaches. By late afternoon all minesweeping necessary to permit a successful landing, and it support and the ensuing unloading, had been accomplished. No mines were found. Reports from firing ships and examination of photographs showed that the principal defensive installations on and behind the eastern beaches, and on their flanks, had been either destroyed or heavily damaged. Among these were included the casemated batteries on the northern and southern flanks of the beaches, which were estimated to have fired on the LCI(G)'s with such telling effect on 17 February. Fragments recovered from LCI(G)'s indicated that the heaviest of these guns were about 150 mm. in caliber. During the evening CTF 52 informed CTF 51 that although weather had prevented expending the full ammunition allowance, and that more installations could be found and destroyed with an additional day of bombardment, he believed a successful landing could be made on 19 February if necessary.

The large staff of an amphibious group commander was needed to achieve coordination of

1-14

the many and mutually conflicting activities at the objective during the prelanding period. The trained teams which are accustomed to working as a well-knot unit in controlling naval gunfire and support aircraft so that each of these weapons will effectively supplement the other are considered to be a necessity, as are the ample communications, photographic, photo interpretation, map reproduction and housing facilities, and working spaces of an AGC. For this operation the staff was augmented by four assistants in the gunnery section, and one assistant and two photo interpreters in the intelligence section. The services of these additional officers were fully employed and a similar arrangement is strongly recommended for future operations of this type. Familiarity with the problems confronting the Amphibious Force, and the presence of the naval gunfire officer of the staff of the Fifth Amphibious Corps, were of material assistance in modifying plans and methods of attacking defensive installations to suit new developments of the situation as they arose. It is believed that factors discussed above will assume added importance in future prelanding operations of larger scope and greater complexity.

From: Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops (Task Force 56)

Enemy Defensive Tactics

The enemy conducted a position defense which was effective, intense, and notable for its economy of forces. No employment of mobile reserves was encountered. There was no withdrawal through a series of defensive lines; there was, in fact, no significant exposure of enemy troops to our supporting arms. The defense depended on the employment of the maximum number of weapons of all calibers fired continuously from well concealed and protected positions until they were destroyed, reduced, or captured. In the initial stages during the hours of darkness the enemy probed our lines in considerable strength employing smoke to cover his concentrations. This activity declined to limited infiltration attempts as our attack progressed. The decentralized sector defense was complete rather than flexible. However, in spite of the high toll it exacted, the defense failed to realize the full value of its weapons. The enemy's decentralized employment of artillery again demonstrated a failure to coordinate or mass the fires of his many weapons or to transfer fires from registered targets to the many targets of opportunity with accuracy or dispatch. It is worthy of note that the majority of casualties in our assault elements, once the beachhead was established, were caused by the intense and accurate small arms fire--to include knee mortars and grenades.

Limitations of Associated and Supporting Arms

The capture of Iwo Jima would have been impossible without the preparatory bombardment and continued support of fire support vessels, carrier and land-based aircraft supplementing the artillery, rockets, tanks, and organic infantry weapons of the landing force. The record tonnage delivered during the assault was effectively directed in close support, and in coordination with the attack of the infantry.

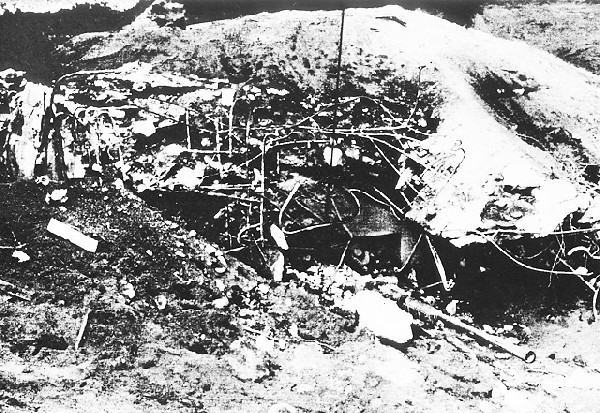

However, our supporting arms were handicapped in their effectiveness by the geographical limitations of the island, the character of the terrain, and the strength of the enemy defenses. The enemy's heavier installations were frequently impervious to field artillery of light and medium calibers and required the destructive power of high velocity main battery naval gunfire.. Artillery was employed both for its destructive effect and to uncover and reveal the location of the many well camouflaged and reinforced caves, bunkers, blockhouses, and pillboxes. The broken configuration of the ground served to mask terrestrial observation, and the natural concealment of enemy positions made air spotting missions difficult. The proximity of our troops to enemy positions, demanded by the exigencies of operations and the necessity to exploit all support, frequently denied us the benefit of adequate heavy fires or bombardment. The coarse volcanic sand in the landing beach areas combined with the nearly impassable topography of Motoyama to impede the movement of tanks, and armored bulldozers had to be used to clear approaches. these tanks, armed with 75-mm. guns and flame throwers, together with self-propelled 75-mm. antitank guns and other antitank weapons, were fired at point-blank ranges.

The result of these limitations was that the burden of reducing many fortifications fell to infantry armed with organic weapons, flame throwers, and demolitions.

1-15

1-16

From: Commander Amphibious Group One (Commander Amphibious Support Force)

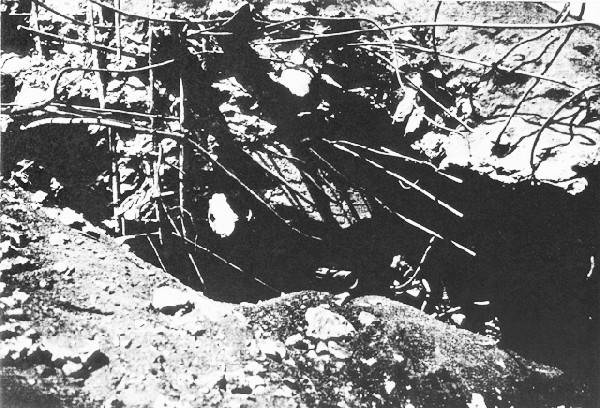

This operation clearly demonstrated that previous high altitude bombings and long range bombardment of Iwo Jima directed only into "target areas" achieved negligible damage to the very numerous defenses of the island, which were stout, comparatively small, and well dispersed. Photographic interpretation shows, on the contrary, that the defenses were substantially increased in number during December, January, and early February. The bombardment by this force on 16 and 17 February also had less than the desired effect, due to interference by weather, to the need for giving way to minesweeping and UDT operations, and by lack of thorough familiarity with the actual important targets, and distinguished from a mark on a map, or a photograph. It was not until after fire support ships, their spotting planes, and the support aircraft had worked at the objective for 2 days, had become familiar with the location and appearance of the defenses, and had accurately attacked them with close range gunfire and low altitude air strikes, that substantial results were achieved. This experience emphasizes once again the need for ample time as well as ample ships, aircraft, and ammunition for preliminary reduction of defenses of a strongly defended position. At the same time it is realized that certain defenses will never be destroyed or even discovered until after the troops land.

From: Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops (Commander Task Force 56)

On 8 November, after a more careful study of the target area had been made, V Amphibious Corps submitted a recommendation for a total of 9 days of preliminary bombardment. On 26 November, the Commander, Amphibious forces, United States Pacific fleet, replied to the recommendation with a study indicating the necessity of slightly more than 3 days of bombardment, and a statement that the troops would be provided with the best possible preliminary bombardment consistent with limitations of ammunition supply and time, and the subsequent troop requirements.

On 24 November, V Amphibious Corps requested that 1 additional day of preliminary bombardments be provided. This letter was forwarded with favorable endorsement by the Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops, Fifth Fleet. The Commander, Amphibious Forces, United States Pacific Fleet, forwarded this request, requesting approval provided that there was no objection on the part of the Commander, Fifth Fleet, based on the general strategical situation.

From: Commanding General, Fourth Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force