Foote, A.H. The African Squadron: Ashburton Treaty: Consular Letters, Reviewed in an Address by Commander A.H. Foote, U.S.N. Philadelphia, PA: William F. Geddes, Printer, 1855.

The Navy Department Library

- Expand navigation for A A

- Abbreviations Used for Navy Enlisted Ratings

- "The Ablest Men"

- Abolishing the Spirit Rations in the Navy

- Account of the Battle of Iwo Jima

- Account of the Operations of the American Navy in France During the War With Germany

- Act providing a Naval Armament

- Action Report, Battle of Okinawa at RP Station #1, 12 April 1945

- Action Report USS LCS(L) (3) 57, Battle of Okinawa at RP Station #1, Apriil 12, 1945

- Advanced Intelligence Centers in the US Navy

- Admiral Caperton in Haiti

- Afghan Wars 1839-42 and 1878-80

- Afghanistan: A Short Account by P.F. Walker

- Afghanistan - Silver Star Presented Francis L. Toner IV

- African Squadron

- Agreement Between the United States and the Republic of Haiti

- Alcohol in the Navy

- The Aleutians Campaign

- Allied Ships present in Tokyo Bay

- Amelia Earhart

- American Naval Mission in the Adriatic, 1918-1921

- American Naval Participation in the Great War (With Special Reference to the European Theater of Operations)

- American Naval Planning Section London

- American Ship Casualties of the World War

- Amphibious Landings in Lingayen Gulf

- Amphibious Operations: Capture of Iwo Jima

- Amphibious Operations - The Planning Phase

- Analysis of the Advantage of Speed and Changes of Course in Avoiding Attack by Submarine

- Anchor of Resolve

- Expand navigation for Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1821

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1822

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1823

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1824

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1825

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1826

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1827

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1828

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1829

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1830

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1831

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1832

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1833

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1834

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1835

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1836

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1837

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1838

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1839

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1840

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1841

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1842

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1843

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1941

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy - 1845

- Anomaly of the Enlisted Officer

- Answering a Call in a Crisis

- Antiaircraft Action Summary

- Antiaircraft Action Summary COMINCH P-009

- Antisubmarine Information, ONI No. 14, 1918

- Antisubmarine Tactics, ONI No. 42, 1918

- Antisubmarine Warfare, ONI No. 9, 1917

- Anti-Suicide Action Summary

- Are the Southern Privateersmen Pirates?

- Arleigh Burke: The Last CNO

- Armed Forces Expeditionary Medals

- Army-Navy E Award

- Articles for the Government of the United States Navy, 1930

- Assault Landings on Leyte Island

- The Assault on Kwajalein and Majuro (Part One)

- Atlantis: The Legendary Island

- Attack on Halifax and Adjacent Territory

- Aviation Personnel Fatalities in World War II

- Awards Manual 1994

- Expand navigation for B B

- Battle of the Atlantic Volume 4 Technical Intelligence From Allied Communications Intelligence

- Battenberg Cup Award

- Battle Experience - Radar Pickets

- Battle Instructions for the German Navy

- Battle for Iwo Jima

- Battle of Derna, 27 April 1805: Selected Naval Documents

- Battle of Guadalcanal

- Battle of Jutland War Game

- Battle of Lake Erie: Building the Fleet in the Wilderness

- Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May 1898

- Battle of Midway: Aerology and Naval Warfare

- Battle of Midway: Army Air Forces

- Battle of Midway: 3-6 June 1942 Combat Narrative

- Battle of Midway: 4-7 June 1942

- Battle of Midway, 4-7 June 1942: Combat Intelligence

- Battle of Midway: 4-7 June 1942 SRH-230

- Battle of Midway - Interrogation of Japanese Officials

- Battle of Midway: Japanese Plans Chapter 5 of The Campaigns of the Pacific War

- Battle of Midway: Preliminaries

- Battle of Midway: U.S. Marine Corps

- Battle of Mobile Bay

- Battle of Mobile Bay: Selected Documents

- Battle of Savo Island August 9th, 1942 Strategic and Tactical Analysis

- Battle of the Atlantic Volume 3 German Naval Communication Intelligence

- Battle of the Atlantic Volume 4 Technical Intelligence From Allied Communications Intelligence

- Battle of the Coral Sea

- Battle of the Coral Sea- Combat Narrative

- Battle of the Nile

- Battle of Tripoli Harbor, 3 August 1804: Selected Naval Documents

- Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom, 1902-1922.

- The Battles of Cape Esperance 11 October 1942 and Santa Cruz Islands 26 October 1942

- Battles of Savo Island and Eastern Solomons

- Bayly's Navy

- Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil

- Bells on Ships

- Bismarck, Sinking of

- Boat Pool 15-1 Manila, P.I. Thanksgiving '22 Nov. 45

- Blockade-running Between Europe and the Far East by Submarines, 1942-44

- Bombing As a Policy Tool in Vietnam

- Expand navigation for Boxer Rebellion and the US Navy, 1900-1901 Boxer Rebellion and the US Navy, 1900-1901

- Brass Monkey

- Brief History of Civilian Personnel in the US Navy Department

- A Brief History of Naval Cryptanalysis

- Brief History of Punishment by Flogging in the US Navy

- Brief History of the Seagoing Marines

- Brief Summary of the Perry Expedition to Japan, 1853

- Bronze Guns (cannons) Glossary

- Budget of the US Navy: 1794 to 2014

- Expand navigation for Building the Navy's Bases in World War II Building the Navy's Bases in World War II

- Bull Ensign

- Bunker Busters: Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator Issues

- Expand navigation for By Sea, Air, and Land By Sea, Air, and Land

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: The Early Years, 1950-1959

- Chapter 2: The Era of Growing Conflict, 1959-1965

- Chapter 3: The Years of Combat, 1965-1968

- Chapter 4: Winding Down the War, 1968 - 1973

- Chapter 5: The Final Curtain, 1973 - 1975

- Medal of Honor Recipients of the U.S. Navy in Vietnam

- Secretaries of the Navy and Key United States Naval Officers, 1950 - 1975

- Aircraft Tailcodes

- Enemy Aircraft Shot Down by Naval Aviators in Southeast Asia

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Expand navigation for C C

- Expand navigation for Cannons of the Washington Navy Yard Cannons of the Washington Navy Yard

- No. 1 Austrian 6-pounder Howitzer with cutout

- No. 1 Austrian 6-pounder Howitzer - Plaque

- No. 2 French 4-pounder Smoothbore

- No. 3 Austrian 6-pounder Howitzer

- No. 4 Austrian 6-pounder Howitzer

- No. 4 Austrian 6-pounder Howitzer - Sight Cutaway

- No. 5 Japanese Gun - Bore 6.875 inches

- No. 6 4-pounder

- No. 6 Austrian 4-pounder

- No. 7 U.S. Army 24-pounder Howitzer

- No. 8 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 9 Spanish 6-pounder

- No. 9 Spanish 6-pounder - Arms

- No. 10 Spanish 27 -pounder

- No. 10 Spanish 27-pounder - Plaque

- No.11 French 12-pounder

- No. 11 French 12-pounder - Le Belliqueux

- No. 11 French 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 11 French 12-pounder - Royal Arms

- No. 12 French 12-pounder

- No. 12 French 12-pounder - Le Vigoureux

- No. 12 French 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 13 Spanish 27-pounder

- No. 13 Spanish 27-pounder - Plaque

- No.14 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 14 Spanish 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 15 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 15 Spanish 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 16 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 16 Spanish 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 17 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 17 Spanish 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 18 Spanish 12-pounder

- No. 18 Spanish 12-pounder - Plaque

- No. 19 Spanish 9-pounder

- No. 19 Spanish 9-pounder - Plaque

- No. 20 Spanish 9-pounder

- No. 20 Spanish 9-pounder - Cambernon

- No. 20 Spanish 9-pounder - Plaque

- No. 21 British Howitzer

- No. 22 British Howitzer

- No. 23 4.63-inch Howitzer

- No. 23 4.63-inch Howitzer

- No. 23 4.63-inch Howitzer - 249

- No. 24 6.5-inch Spanish Howitzer

- No. 25 Venetian 5.75-inch Howitzer

- No. 25 Venetian 5.75-inch Howitzers

- No. 26 Venetian 5.75-inch Howitzer

- Flagpole and Mortars

- Flagpole and Mortars - Base

- Flagpole and Mortars - Mortar

- The Navy Museum

- View Along Dahlgren Avenue

- Captain Raphael Semmes and the C.S.S. Alabama

- Captain Samuel Nicholson: A Monograph [pdf]

- Capture of CSS Florida by USS Wachusett - Report of Commander Napoleon Collins

- Capture of CSS Florida by USS Wachusett - Report of Lieutenant Morris

- Capture of the Frigate USS Philadelphia

- Caribbean Tempest: The Dominican Republic Intervention of 1965

- Carrier Deployments During the Vietnam Conflict

- Carrier Locations - Pearl Harbor Attack

- Carrier Strikes on the China Coast

- Case of the Somers' Mutiny 1843

- Casualties: US Navy & Marine Corps Personnel

- Casualties: US Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Killed and Injured in Selected Accidents and Other Incidents Not Directly the Result of Enemy Action

- Change of Command and Retirement Ceremony of the Commandant Naval District, Washington, DC

- Change of Command Ceremony

- Charles Morris A Man of Letters and Numbers

- Chart Your Future As A Woman Officer

- Chester Nimitz and the Development of Fueling at Sea

- Christmas 1932 U.S. Naval Air Station San Diego California

- CIC [Combat Information Center] Manual (RADSIX)

- CIC [Combat Information Center] Operation in an AGC

- CIC [Combat Information Center] Yesterday and Today

- CIC Operations On a Night Carrier

- CINCPAC Glossary of Commonly Used Abbreviations and Short Titles

- Expand navigation for CinCPac Report - Pearl Harbor CinCPac Report - Pearl Harbor

- Circular September 13, 1839

- Circular 17 July, 1869

- Colored Persons in the Navy of the U.S. (1842)

- Combined Operation Craft: Small Scale Drawings

- COMINT [Communications Intelligence] Contributions [to] Submarine Warfare in WW II

- Command and Control of Air Operations in the Vietnam War

- Commander Task Force Seventeen Operation Plan 1-45

- Commander's Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations

- Comparison of Military and Civilian Equivalent Grades

- Compilation of Enlisted Ratings and Apprentiships US Navy 1775-1969

- Composition of Japanese Forces

- Composition of US Forces

- Condition of the Navy and Its Expenses 1821

- Conduct of War at Sea

- Conflict and Cooperation: The U.S. and Soviet Navies in the Cold War

- Constitution Fighting Top

- The Constitution Gun Deck

- Constitution Sailors in the Battle of Lake Erie [pdf]

- Continental Congress and the Navy

- The Continental Navy: "I Have Not Yet Begun to Fight."

- Copy of talk given by Captain B.E. Manseau, USN, before the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the Society of Naval Architets and Marine Engineers

- Cordon of Steel

- The Corps' Salty Seadogs Have All But Come Ashore: Seagoing Traditions Founder as New Millennium Approaches

- Costs of Major US Wars

- Cruising Fleets

- Cruising in the Old Navy

- Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962

- Expand navigation for Cuban Missile Crisis Cuban Missile Crisis

- Current Doctrine Submarines

- Cursor scales for the VG [Plan Position Indicator (radar)

- Customs and Traditions, Navy

- Expand navigation for Cannons of the Washington Navy Yard Cannons of the Washington Navy Yard

- Expand navigation for D D

- D-Day, the Normandy Invasion: Combat Demolition Units

- Dartmoor Prison

- Decatur House and Its Distinguished Occupants

- Declarations of War and Authorizations for the Use of Military Force

- The Defense and Burning of Washington in 1814: Naval Documents of the War of 1812

- De Klerk Diary

- Demolition Units of the Atlantic Theatre of Operations

- Department of Defense Acronyms

- Destroyers at Normandy

- Destroyers for Bases Agreement, 1941

- Destroyers transferred to Britain under Destroyers for Bases agreement

- Destruction of CSS Albemarle - Report of A. F. WARLEY

- Destruction of CSS Albemarle - Report of Lieutenant William Barker Cushing

- The Development of Japanese Sea Power: "Know Your Enemy"! [CinCPOA Bulletin 93-45, 1945]

- Expand navigation for The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869 The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869

- Digest Catalogue of Laws and Joint Resolutions: The Navy and the World War

- Disaster at Savo Island, 1942

- Disaster in the Pacific

- Discipline in the U.S. Navy

- Expand navigation for Diving in the U.S. Navy: A Brief History Diving in the U.S. Navy: A Brief History

- Documents, Official and Unofficial, Relating to the Capture and Destruction of the Frigate Philadelphia at Tripoli - 1850

- Documents Related to the Resignation of the German Commander in Chief, Navy, Grand Admiral Raeder and to the Decommissioning of the German High Seas Fleet

- DoD Rules for Military Commissions - 2006

- Expand navigation for Dominican Republic Intervention Dominican Republic Intervention

- Doolittle Raid

- The DRVN Strategic Intelligence Service

- Expand navigation for E E

- Early Raids in the Pacific Ocean

- Elementary Map and Aerial Photograph Reading

- Emancipation Proclamation, Navy general Order No. 4, 1863

- Employment of Naval Forces

- Enlisted Uniforms

- Enlistment, Training, and Organization of Crews for Our New Ships

- Essay on Naval Battles of the Korean War

- Establishment of the Department of the Navy

- Establishment of the Navy

- Exercise Tiger

- Exorcizing the Devil's Triangle

- Expeditions, Diplomatic and Scientific Activity, and Operations Against Native Americans and Pirates

- Exploring the Antarctic 1840 - The Wilkes Expedition

- Eye-Witness Account of the Battle Between the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia Mar 9 1862

- Evolution of Naval Weapons

- Expand navigation for F F

- Far Eastern Sighting Guide [ONI-F-31 FE]

- Fifty Years of Naval District Development 1903-1953

- Filipinos in the United States Navy

- Final Contact: USS Indianapolis (CA-35) passes USS LST-779 29 July 1945

- The First Raid on Japan

- Fixing Wages and Salaries of Navy Civilian Employees

- Flag Sizes

- Fleet Air Wing Four Strikes

- Fleet Post Office, New York, New York

- Fleet Post Office, San Francisco, California

- "Forward ... From the Start": The U.S. Navy & Homeland Defense: 1775-2003

- Fourth of July Dinner the Spirit of '45

- French Indo-China PSIS 400-35

- Frocking

- From Dam Neck to Okinawa: A Memoir of Antiaircraft Training in World War II

- From the Sea to the Stars

- Expand navigation for G G

- GAF (German Air Force, Luftwaffe] and the Invasion of Normandy

- Gearing Up for Victory American Military and Industrial Mobilization in World War II

- Gedunk

- General Information for Employees - Washington Navy Yard - 1941

- General Instructions for Commanding Officers of Naval Armed Guards on Merchant Ships - 1944

- General Instructions for Sloops and Torpedo Craft

- General Mess Manual and Cook Book

- Expand navigation for General Orders General Orders

- General Order (21 January 1834) Presents

- General Order (28 November 1838) Animals

- General Order (18 February 1846) Port and Starboard

- General Order (17 December 1850) Furnishing Vessels

- General Order (27 September 1851) Contracts of Enlistment Ending

- General Order (17 May 1858) Naval Academy Graduates Denied Letter

- General Order (22 April 1862) Officers Forbidden to Give Publicity to Any Hydrographical Knowledge

- General Order (12 December 1862) Rules for Naval Communication

- General Order (23 December 1862) Rules Corresponding with SecNav and Bureaus

- General Order No. 1 (1863) Rules to Disseminate General Orders

- General Order No. 4 (1863) Emancipation Proclamation

- General Order No. 9 (1863) Observance of Paroles

- General Order No. 51 (1865) Announcing Death President Abraham Lincoln

- General Order No. 73 (1866) Resolution of Thanks from Congress to Admiral Farragut for Mobile Bay Action

- General Order No. 81 (1866) Requirements of Guardians for Boy to Enlist

- General Order No. 83 (1867) Proclamation Issued by President Johnson

- General Order No. 90 (1869) Uniform Changes

- General Order No. 99 (1869) Authority Given to Fleet Officers

- General Order No. 105 (1869) North & South Pacific Squadrons Combined into Pacific Station

- General Order No. 110 (1869) Forbidding Applications for Duty Through Persons of Influence

- General Order No. 112 (1869) Sea Service of Officers to be Three Years

- General Order No. 123 (1869) Uniform Change for Masters, Ensigns & Midshipmen

- General Order No. 127 (1869) List of Types of Officers to Mess in Second Ward Room

- General Order No. 128 (1869) Exercises for Ships with Sails

- General Order No. 131 (1869) Economizing the Use of Coal

- General Order No. 175 (1872) Division of the Pacific Station into Two Stations

- General Order No. 226 (1877) Importance of Complete Reports and Logs

- General Order No. 230 (1877) Special Shore Service and Duty

- General Order No. 232 (1877) Working Hours at Navy Yards and Stations

- General Order No. 248 (1880) Correct and General Understanding of Signals

- General Order No. 250 (1880) Establishment of the Office of Judge Advocate General of the Navy

- General Order No. 252 (1880) Painting Schematic for Boats

- General Order No. 292 (1882) Establishment of the Office of Intelligence

- General Order No. 370 (1889) Copies of Books to the Navy Department Library

- General Order No. 372 (1889) Order for Official Communications

- General Order No. 544 (1900) Establishment of the General Board

- General Order No. 55 (1901) Decorations for Philippine Islands and Boxer Rebellion

- General Order No. 56 (1901) Puget Sound, Naval Station to Navy Yard

- General Order No. 128 (1903) Establishment of Naval Districts

- General Order No. 129 (1903) Surplus Provisions

- General Order No. 74 (1908) Establishing Ship Post Offices

- General Order No. 135 (1911) Definitions of Well-known Naval Terms

- General Order No. 30 (1913) Movement of the Rudder

- General Order No. 98 (1914) Movement of the Rudder

- General Order No. 99 (1914) Prohibition in the Navy

- General Order No. 132 (1915) Khaki Dye for White Undress Uniform

- General Order No. 258 (1917) SecNav Announces Death of Admiral Dewey

- General Order No. 259 (1917) Executive Order and Message on Death of Admiral Dewey

- General Order No. 294 (1917) Identification Tags ("Dog Tags")

- General Order No. 456 (1919) Observance of the Sabbath Day

- General Order No. 541 (1920) Standard Nomemclature for Naval Vessels

- General Order No. 244 [1934] Alcoholic Liquors

- General Order No. 47 (1935) Precedence of Forces in Parades

- General Orders 1921-1935

- General Orders for the Regulation of the Navy Yard Washington, D.C. - 1833-1850

- General Orders USS Independence 1815

- German Commanders Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl on the Invasion of Normandy in 1944

- German Defense of Berlin

- Expand navigation for German Espionage and Sabotage German Espionage and Sabotage

- German Report on the Allied Invasion of Normandy

- German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast

- German Submarine Attacks

- German Submarines in Question and Answer

- Expand navigation for Glossary of U.S. Naval Code Words (NAVEXOS P-474) Glossary of U.S. Naval Code Words (NAVEXOS P-474)

- Going back to civilian life facts you should know about

- going back to civilian life - a pamphlet

- Going South: U.S. Navy Officer Resignations & Dismissals On the Eve of the Civil War

- Grand Strategy Contending Contemporary Analyst Views & Implications for the US Navy

- The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads and the Norfolk Naval Hospital

- Greely Relief Expedition

- Expand navigation for Grenada: Operation Urgent Fury Grenada: Operation Urgent Fury

- Guadalcanal Campaign

- Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel NAVPERS-15092

- Guidelines: Naval Social Customs

- Guide to US Military Casualty Statistics

- The Guidebook for NAVAL RESERVE CHAPLAINS

- General Description of the Whitehead Torpedo

- Expand navigation for H H

- Haitian Campaign of 1915

- Haiti - US Navy Medal of Honor - 1915

- Halsey-Doolittle Raid

- Handbook of First Aid Treatment for Survivors of Disasters at Sea

- Head - Ship's Toilet

- Historical Approach to Warrant Officer Classifications

- The Historical Importance to Navigation of Nathaniel Bowditch's New American Practical Navigator

- History and Descriptive Guide of the US Navy Yard Washington, DC

- History of Convoy and Routing [1945]

- History of Flag Career of Rear Admiral W.B. Caperton

- History of Paul Jones, the Pirate

- History of the Bureau of Engineering During WWI

- History of the Chief Petty Officer

- History of the Dudley Knox Center for Naval History

- History of the Navy Department Library

- Expand navigation for History of the Seabees History of the Seabees

- Expand navigation for History of the US Navy History of the US Navy

- Expand navigation for History of United States Naval Operations: Korea History of United States Naval Operations: Korea

- Foreword - History of US Naval Operations: Korea

- Preface - History of US Naval Operations: Korea

- List of Maps - History of US Naval Operations: Korea

- List of Tables - History of US Naval Operations: Korea

- Chapter 1: To Korea By Sea

- Chapter 2: Policy and Its Instruments

- Chapter 3: War Begins

- Chapter 4: Help on the Way

- Chapter 5: Into the Perimeter

- Chapter 6: Holding the Line

- Chapter 7: Back to the Parallel

- Chapter 8: On to the Border

- Chapter 9: Retreat to the South

- Chapter 10: The Second Six Months

- Chapter 11: Problems of a Policeman

- Chapter 12: Two More Years

- A Note on Source Materials

- Glossary of Naval Abbreviations

- History of US Navy Uniforms 1776 - 1981

- Expand navigation for Honda (Pedernales) Point, California, Disaster, 8 September 1923 Honda (Pedernales) Point, California, Disaster, 8 September 1923

- Honda (Pedernales) Point, California, Disaster, 8 September 1923

- How the Navy Talks

- How to Fold Your Navy Uniform

- How to Mark Your Navy Uniform

- How to serve your country in the WAVES

- The Hungnam and Chinnampo Evacuations

- Hurricanes and the War of 1812

- History and aims of the Office of Naval Intelligence

- Expand navigation for I I

- I Was a Yeoman (F)

- Identification Tags - Dog Tags

- In Honor of Master Chief Britt K Slabinski: United States Navy, Retired: MEDAL OF HONOR - HALL OF HEROES INDUCTION CEREMONY- THE PENTAGON AUDITORIUM- 25 MAY 2018

- In Memory of CTIC(IW/EXW) Shannon M. Kent

- Incredible Alaska Overland Rescue

- Indians in the War 1945

- Expand navigation for Influenza Influenza

- 1918 Influenza by Vice Admiral Albert Gleaves, Commander of Convoy Operations in the Atlantic, 1917-1919.

- Admiral William B. Caperton of the 1918 Influenza on Armored Cruiser No. 4, USS Pittsburgh

- A Forgotten Enemy: PHS's [Public Health Service] Fight Against the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

- Great Flu Crisis at Mare Island Navy Yard.

- Influenza at the United States Naval Hospital, Washington, D.C.

- The Influenza Epidemic of 1918 by Carla R. Morrisey, RN, BSN

- Influenza of 1918 (Spanish Flu) and the US Navy

- Influenza on a Naval Transport

- Influenza-Related Medical Terms

- The Pandemic of Influenza in 1918-1919

- Philadelphia, Nurses, and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918

- A Winding Sheet and a Wooden Box

- Information in Relation to the Naval Protection Afforded to The Commerce of the United States in the West India Islands, &c. &c.

- Injury and Destruction of Navy Vessels by Earthquakes, Dec. 1868

- Inquiry Into Occupation and Administration of Haiti and the Dominican Republic

- Instances of Use of US Armed Forces Abroad, 1798 - 2004

- Instructional Material for the Fight Against Enemy Propaganda

- Instructions for the examination and entry into United States Ports in time of war

- Instructions on Reception, Care and Training of Homing Pigeons

- Inter-Allied Naval Relations and the Birth of NATO

- Interrogation of General Alfred Jodl

- Interrogations of Japanese Officials - Vol. I & II

- Invasion of Sicily

- The Invasion of Southern France: Aerology and Amphibious Warfare

- Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy

- Iran Hostage - Rescue Mission Report

- Irregular Enemies and the Essence of Strategy

- Irregular Warfare Special Study

- Instructions for Painting and Cementing Vessels of the United States Navy

- Expand navigation for J J

- Japan's Struggle to End the War - 1946

- Japanese Interrogation Of Prisoners Of War

- Japanese Naval and Merchant Shipping Losses - WWII

- Japanese Naval Ground Forces

- Japanese Naval Shipbuilding

- Japanese Operational Aircraft CinCPOA 105-45

- Japanese Operational Aircraft CinCPOA 105-45 Revised

- Japanese Radio Communications and Radio Intelligence CinCPOA 5-45

- Japanese - Smithsonian War Background Study

- Expand navigation for Japanese Story of the Battle of Midway Japanese Story of the Battle of Midway

- Java Sea Campaign

- John Paul Jones

- John Paul Jones

- Journal of the Disasters in Afghanistan, 1841-2

- Expand navigation for K K

- Kite Balloons in Escorts

- Kosovo Naval Lessons Learned During Operation Allied Force

- Expand navigation for Korean War Chronology Korean War Chronology

- Korean War Interim Evaluation No 1

- Expand navigation for L L

- Lost of Flight 19 Official Accident Reports

- Landing Operations Doctrine, USN, FTP-167

- Expand navigation for Law of Naval Warfare: NWIP 10-2, 1955 Law of Naval Warfare: NWIP 10-2, 1955

- Law of Naval Warfare: Chapters 1 - 6

- Appendix A: Convention For the Adaption to Maritime War of the Principles of the Geneva Convention - X Hague, 1907

- Appendix B: Convention Concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Maritime War - XIII Hague, 1907

- Appendix C: Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick

- Appendix D: Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea of August 12, 1949

- Appendix E: Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949

- Appendix F: Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of August 12, 1949

- Appendix G-I

- Lend Lease Act, 11 March 1941

- Letter from President Harry S. Truman to Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal regarding the Five-Star Rank

- Lengthy Deployment: The Jeannette Expedition In Arctic Waters

- Letter to Mr. Ride

- Library Regulations - USS Pittsburgh

- Limited Duty Officer

- List of Authorized Abbreviations for Use in Bureau of Naval Personnel Messages (1958)

- List of Expeditions 1901-1929

- List of Patrol Squadron Deployments to Korea During the War

- Living Conditions in the 19th Century US Navy

- Log of the trip of the president to the Casablanca Conference 9-31 January, 1943

- The Logistics of Advance Bases

- Look at YOU in the United States NAVY

- Lookout Manual 1943

- Loss of Flight 19 Official Accident Reports

- Lost Patrol

- LSU Squadron Two Thanksgiving Dinner November 22 1951

- The Landings in North Africa

- Expand navigation for M M

- Magic Background of Pearl Harbor

- Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 2

- Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 2 Appendix

- Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 4

- Main Navy Building: Its Construction and Original Occupants

- Manual for Buglers, US Navy

- Manual of Commands and Orders, 1945

- Manual of Information Concerning Employments for the Panama Canal Service

- Marine Amphibious Landing in Korea, 1871

- Market Time (U) CRC 280

- Master File Drawings of German Naval Vessels

- Matthew Fontaine Maury: Benefactor of Mankind

- Menu Thanksgiving Day November 27, 1913

- Merchant Marines

- Merchant Ship Shapes

- Mers-el-Kebir Port Instructions for Merchant Vessels [1942]

- Mess Night Manual

- Midway in Retrospect: The Still Under Appreciated Victory

- Midway’s Operational Lesson: The Need For More Carriers

- Midway: Sheer Luck or Better Doctrine?

- Midway's Strategic Lessons

- Midway Plan of the Day Notes

- Military Sealift Command

- Military Service Records and Unit Histories

- Mine Sweeping Manual 1917

- Mine Warfare

- Mine Warfare in South Vietnam

- Expand navigation for Miracle Harbor Miracle Harbor

- Miscellaneous Actions in the South Pacific

- More Bang for the Buck: U.S. Nuclear Strategy and Missile Development 1945-1965

- My days aboard U.S.S. Santa Fe

- Expand navigation for N N

- Naming of Streets, Facilities and Areas On Naval Installations

- Narrative of Captain W.S. Cunningham, US Navy Relative to events on Wake Island in December 1941, and subsequent related events

- Narrative of Joshua Davis an American Citizen 1811

- Narrative of the Capture, Sufferings and Escape of Capt. Barnabas Lincoln

- Narrative of the March and Operations of the Army of the Indus

- Narrative of the United States' Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea

- Navajo Code Talker Dictionary

- Navajo Code Talkers: World War II Fact Sheet

- Naval Anecdotes Relating to HMS Leopard Versus USS Chesapeake, 24 June 1807.

- Expand navigation for Naval Armed Guard Service in World War II Naval Armed Guard Service in World War II

- Expand navigation for The Naval Bombing Experiments The Naval Bombing Experiments

- Naval District Manual 1927

- Naval Districts

- Naval Gun Factory (Washington Navy Yard) Facilities Data: World War II

- Naval Guns at Normandy

- Naval Memorial Service, Casting Flowers on the Sea in Honor of the Naval Dead

- Expand navigation for The Naval Quarantine of Cuba The Naval Quarantine of Cuba

- Naval Yarns by Captain Bartlett [manuscript]

- The Navy by Michael A. Palmer

- Navy and Defense Reform: A Short History and Reference Chronology

- Expand navigation for Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual [Rev. 1953] Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual [Rev. 1953]

- Pt. 1 - Personal Decorations

- Pt. 2 - Unit Awards

- Pt. 3 - Special and Commemorative Medals

- Pt. 4 - Campaign and Service Medals

- Pt. 5 - Decorations Awarded By Foreign Governments

- Pt. 6 - Other Federal Decorations (non-military)

- Index

- Memo - Changes

- Ships & Other Units Eligible for the Korean Service Medal

- Navy at a Tipping Point - 2010

- Navy Civil War Chronology

- The Navy Department A brief history until 1945

- Navy Department Communiques 1-300 and Pertinent Press Releases

- Navy Department Communiques 301 to 600

- Navy Filing Manual 1941

- Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans - 2016

- The Navy in the Cold War Era, 1945-1991

- Navy Interdiction Korea Vol. II

- Navy Nurse Corps General Uniform Instructions 1917

- The Navy of the Republic of Vietnam

- Navy Records and [Navy Department] Library (E Branch)

- Navy Regulations, 1814

- Navy Ship Procurement: Alternative Funding Approaches

- Navy Ship Propulsion Technologies - 2006

- Navy Shipboard Lasers for Surface, Air, and Missile Defense

- Navy-Yard, Washington, History by Hibben

- The Navy's World War II-era Fleet Admirals

- Expand navigation for Needs and Opportunities in the Modern History of the U.S. Navy Needs and Opportunities in the Modern History of the U.S. Navy

- Forward Presence in the Modern Navy: From the Cold War to a Future Tailored Force

- Historiography of Programming and Acquisition Management since 1950 - Hone

- Historiography of Technology Since 1950

- Naval Personnel since 1945: Areas for Historical Research

- Navy, Science, and Professional History

- The Social History of the U.S. Navy, 1945–Present

- U.S. Navy’s Role in National Strategy

- Writing U.S. Naval Operational History 1980–2010

- Negro in the Navy - 1947

- Negro in the Navy by Miller

- Neutrality Instructions US Navy 1940

- New Equation: Chinese Intervention into the Korean War

- A New Look at the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Nixon's Trident: Naval Power in Southeast Asia, 1968-1972 by John D. Sherwood

- Nomenclature of Decks

- Nomenclature of Naval Vessels

- Non-Discrimination in V-12 Program

- Northern Barrage and Other Mining Activities

- Northern Barrage: Taking Up Mines

- Northern Formosa, Pescadores

- Notes on Anti-submarine Defenses ONI Publication No. 8

- Notes on Writing Naval (not Navy) English

- Expand navigation for O O

- Occupation of Kiska

- Occupation of the Gilbert Islands

- The Offensive Navy Since World War II: How Big and Why, A Brief Summary

- Office of Naval Records and Library 1882-1946

- Officers and Key Personnel Attached to the Office of Naval Records and Library 1882-1946

- Officers of the Continental Navy and Marine Corps

- Officers of Navy Yards, Shore Stations, and Vessels, 1 January 1865

- Expand navigation for Officers of the Continental and U.S. Navy and Marine Corps 1775-1900 Officers of the Continental and U.S. Navy and Marine Corps 1775-1900

- Marine Corps Officers: 1798-1900

- Continental Navy Officers: 1775-1785

- Continental Marine Corps Officers: 1775-1785

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (A)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (B)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (C)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (D)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (E)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (F)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (G)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (H)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (I)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (J)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (K)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (L)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (M)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (N)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (O)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (P)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (Q)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (R)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (S)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (T)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (U)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (V)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (W)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (Y)

- Navy Officers: 1798-1900 (Z)

- "Official" USS Missouri Survival Guide

- Expand navigation for Operation Crossroads Operation Crossroads

- Expand navigation for Operation NEPTUNE - The Invasion of Normandy Operation NEPTUNE - The Invasion of Normandy

- Table of Contents - Operation NEPTUNE

- Editor's Note - Operation Neptune

- Chapter 1: THE STRATEGIC BACKGROUND OF OVERLORD

- Chapter 2: PLANNING AND PREPARATION FOR CROSS-CHANNEL (OVERLORD) OPERATIONS

- Chapter 3: THE STRATEGIC BACKGROUND OF OVERLORD

- Chapter 4: NEPTUNE OPERATIONS PLANS

- Chapter 5: Naval Preparations for Cross-Channel Operations

- Chapter 6: The Operation Begins

- Chapter 7: Defensive Measures - NEPTUNE Operation

- Chapter 8: Bombardment and Other Defensive Operations Against Enemy Land Forces

- Chapter 9: The NEPTUNE Assaults

- Chapter 10: The Build-up for the Battle of France

- Operation NEPTUNE - Index

- Operation NEPTUNE Administrative History's Table of Contents

- Expand navigation for Operation Neptune Operation Neptune

- Operations of the Navy and Marine Corps in the Philippine Archipelago

- Operations of the Seventh Amphibious Force

- Operations of USS Don Juan de Austria

- OPNAV [Office of the Chief of Naval Operations] Acronyms

- Origin of Navy Terminology

- Our Vanishing History and Traditions - Knox

- Operation of the Admiral Scheer

- Our Navy at War

- Expand navigation for P P

- Expand navigation for Pacific Typhoon, 18 December 1944 Pacific Typhoon, 18 December 1944

- Admiral Nimitz's Pacific Fleet Confidential Letter on Lessons of Damage in Typhoon

- List of Commands and Ships Involved

- Personnel Casualties Suffered by Third Fleet, 17-18 December 1944, Compiled from Official Sources

- Aircraft Losses Suffered by Third Fleet, 17-18 December 1944, Compiled From Official Sources

- Extracts Relating to the Typhoon from Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet Report

- Oral History

- Expand navigation for Pacific Typhoon, June 1945 - Reports Pacific Typhoon, June 1945 - Reports

- Pacific Typhoon October 1945 - Okinawa

- Peacekeeping and Related Stability Operations: Issues of U.S. Military Involvement

- The Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941 - Overview

- Pearl Harbor Navy Medical Activities

- Expand navigation for "Pearl Harbor Revisited: USN Communications Intelligence" "Pearl Harbor Revisited: USN Communications Intelligence"

- Pearl Harbor Salvage Report 1944

- Pearl Harbor Submarine Base 1918-1945

- Expand navigation for Pearl Harbor: Survivor Reports Pearl Harbor: Survivor Reports

- USS Arizona - Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS California- Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS Maryland - Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS Oklahoma - Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS Tennessee - Report by Survivor of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS West Virginia - Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack

- Pearl Harbor: Why, How, Fleet Salvage and Final Appraisal

- Pentagon 9/11

- Expand navigation for Personal Identification Tags or "Dog Tags" Personal Identification Tags or "Dog Tags"

- Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques

- Expand navigation for Philadelphia Experiment Philadelphia Experiment

- Phonetic Alphabet and Signal Flags

- The Pioneers - A Monograph on the First Two Black Chaplains in the Chaplains Corps of the United States Navy

- The Pivot Upon Which Everything Turned

- Plea in Favor of Maintaining Flogging in the Navy

- Pocket Guide to Japan

- Pocket Guide to Netherlands East Indies

- Pocket Guide to New Guinea and the Solomons

- Expand navigation for Port Chicago, CA, Explosion Port Chicago, CA, Explosion

- Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: A Sketch

- Post Mortem CIC [Combat Information Center] Notes

- Post Mortems on Enemy Ships

- Potato Famine of 1847

- Precisely Appropriate for the Purpose

- Preserving an Honored Past

- Priceless Advantage by FD Parker

- Propaganda Foreign Military Studies 1952

- Public Law 333, 79th Congress

- Expand navigation for Pacific Typhoon, 18 December 1944 Pacific Typhoon, 18 December 1944

- Expand navigation for Q Q

- Expand navigation for R R

- Radio Intelligence Appreciations Concerning German U-Boat Activity in the Far East

- Radio Proximty (VT) Fuzes

- Ready Seapower: A History of the US Seventh Fleet by Edward J. Marolda [pdf]

- Recollections of Capture by the Germans, Imprisonment, and Escape of Lieutenant Edouard Victor Isaacs, U.S.N.

- Recollections of Ensign Leonard W. Tate

- Recollections of Lieutenant Commander William Leide

- Recollections of Lieutenant Wilton Wenker and Lieutenant Elby Concerning the Crossing of the Rhine River in 1945

- Recollections of USS Pampanito's rescue of prison ship survivors by Lieutenant Commander Landon Davis

- Recollections of Vice Admiral Alan G. Kirk Concerning the Crossing of the Rhine River in 1945

- Reestablishment of the Marine Corps

- Expand navigation for Registers of the Navy Registers of the Navy

- Register of the Navy, 1812

- Register of the Navy, 1814

- Register of the Navy, 1815

- Register of the Navy, 1816

- Register of the Navy, 1818

- Register of the Navy, 1819

- Register of the Navy, 1820

- Register of the Navy, 1821

- Register of the Navy, 1822

- Register of the Navy, 1823

- Register of the Navy, 1824

- Register of the Navy, 1825

- Register of the Navy, 1826

- Register of the Navy, 1827

- Register of the Navy, 1829

- Register of the Navy, 1830

- Register of the Navy, 1831

- Register of the Navy, 1832

- Register of the Navy, 1833

- Register of the Navy, 1834

- Register of the Navy, 1836

- Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814

- Register of USN & USMC Officer Personnel 1801-1807 [pdf]

- Regulation, December 7, 1841

- Regulations for the Information of Officers On Neutrality Duty in Connection With the Visits of Belligerent Vessels of War [1916]

- Regulations For Powder Magazines and Shell Houses 1874

- Regulations Governing the Uniform of Commissioned Officers 1897

- Reincarnation of John Paul Jones The Navy Discovers Its Professional Roots

- Religions of Vietnam

- Remarks on Protection of a Convoy by Extended Patrols

- Remarks on Submarine Tactics Against Convoys

- Reminiscences of Seattle Washington Territory and the U. S. Sloop-of-War Decatur

- Reminiscences of Seattle Washington Territory and the US Sloop-of-War Decatur During the Indian War of 1855-56

- Report by the Special Subcommittee on Disciplinary Problems in the US Navy

- Reports of Arica, Peru Earthquake from USS Powhatan and USS Wateree

- Republic of Korea Navy

- Resolution of the Continental Congress, 11 December 1775

- Resolution of the Continental Congress, 25 November 1775

- Hyman G. Rickover's Promotion to Admiral [H.A.S.C. 93-16]

- Ringle Report on Japanese Internment

- Riverine Warfare Manual [1971]

- Riverine Warfare: The US Navy's Operations on Inland Waters

- Rocks and Shoals: Articles for the Government of the U.S. Navy

- The Recruitment of African Americans in the US Navy 1839

- The Role of COMINT in the Battle of Midway

- The Role of the United States Navy in the Formation and Development of the Federal German Navy, 1945-1970

- Rommel and the Atlantic Wall

- Royal Works USS Lexington [Crossing the Line 1936]

- Rules for the Regulation of the Navy - 1775

- The Russian Navy Visits the United States

- Expand navigation for S S

- SACO

- Expand navigation for Sailors as Infantry in the US Navy Sailors as Infantry in the US Navy

- The Sailors Creed

- Samoan Hurricane

- A Sampling of U.S. Naval Humanitarian Operations

- Expand navigation for Seabee History Seabee History

- Secretary of the Navy's Report for 1900 on the China Relief Expedition

- Expand navigation for Selected Documents of the Spanish American War Selected Documents of the Spanish American War

- Battle of Manila Bay

- Battle of Manila Bay: Miscellaneous Documents

- Olympia in Battle of Manila Bay

- Raleigh in Battle of Manila Bay

- Concord in Battle of Manila Bay

- Baltimore in Battle of Manila Bay

- Petrel in Battle of Manila Bay

- Boston in Battle of Manila Bay

- McCulloch in Battle of Manila Bay

- U.S. Consul at Manila

- Official Spanish Report on Battle of Manila Bay

- Expand navigation for Selected Groups in the Republic of Vietnam Selected Groups in the Republic of Vietnam

- Seventh Amphibious Force - Command History 1945

- Shelling of the Alaskan Native American Village of Angoon, October 1882

- Ship to Shore Movement

- Ship Shapes Anatomy and types of Naval Vessels

- Shipboard Ettiquette [Naval R. O. T. C. Pamphlet No. 16]

- Shiploading - A Picture Dictionary

- Expand navigation for Ships named for Individual Sailors Ships named for Individual Sailors

- Ships Present at Pearl Harbor

- Ships Sunk and Damaged in Action during the Korean Conflict

- A Short Account of the Several General Duties of Officers, of Ships of War: From an Admiral, Down to the Most Inferior Officer

- Short Guide to Iraq

- The Sicilian Campaign, Operation 'Husky'

- Signals for the Use of the Navy of the Confederate States

- Sinking of C.S.S. Alabama by U.S.S. Kearsarge - 19 Jun 1864

- Expand navigation for Sinking of the Bismarck Sinking of the Bismarck

- Sinking of the USS Guitarro

- The Sinking of the USS Housatonic by the Submarine CSS H.L. Hunley

- Expand navigation for Sinking of USS Indianapolis - Press Releases & Related Sources Sinking of USS Indianapolis - Press Releases & Related Sources

- Expand navigation for Skill in the Surf: A Landing Boat Manual Skill in the Surf: A Landing Boat Manual

- Chapter I. Landing Boats Are Important!

- Chapter II. Landing Craft From Troy to Tokio

- Chapter III. Know Your Boat!

- Chapter IV. Know Your Job!

- Chapter V. Keep It Running!

- Chapter VI. The Coxswain Takes Over

- Chapter VII. Learning the Ropes

- Chapter VIII. The Salvage Boat

- Chapter IX. Where Sea Meets Land

- Chapter X. Hit That Beach!

- Chapter XI. Information, Please!

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

- Appendix E

- Appendix F

- Appendix G

- Appendix H

- Appendix I

- Appendix J

- Skunks, Bogies, Silent Hounds, and the Flying Fish

- Slapton Sands: The Cover-up That Never Was

- Small Wars Their Principles and Practice

- Smith, Melancton Rear Admiral USN A Memoir

- Smoker Sat., July 27, 1918 U.S.S. Arizona

- So You are Going to the South Pacific?

- Soldier's Guide Bosnia-Herzegovina

- Solomon Islands Campaign: I The Landing in the Solomons

- Solomon Islands Campaign: II Savo Island & III Eastern Solomons

- Solomon Islands Campaign: IV Battle of Cape Esperance

- Solomon Islands Campaign VII Battle Tassafaronga

- Solomon Islands Campaign IX Bombardments of Munda and Vila-Stanmore

- Solomon Islands Campaign: X Operations in the New Georgia Area 21 June-5 August 1943

- Solomon Islands Campaign: XI Kolombangara and Vella Lavella 6 August - 7 October 1943

- Solomon Islands Campaign XII The Bougainville Landing and the Battle od Empress Augusta Bay, 27 October - 2 November 1943

- Some Experiences Reported by the Crew of the USS Pueblo and American Prisoners of War from Vietnam

- Some Memorandums Construction of Ships Frederick Tudor

- Somers, essay on legal aspects of Somers Affair

- Sources on US Naval History by State

- Expand navigation for Spanish American War Spanish American War

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 1

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 2

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 3

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 4

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 5

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 6

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 7

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 8

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 9

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 10

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 11

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 12

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 13

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1898 Part 14

- Spanish-American War; War Plans and Impact on U.S. Navy

- Special Order 1865 April 17 Assemblage of Officers to Attend

- Special Order 1865 April 17 Navy Department Closure

- Special Order 1865 April 17 Officers to Attend Funeral

- Special Order 1865 April 20 List of Officers to Accompany Remains

- Special Order No. 73 - 1905 April 18 Travel Pay

- Expand navigation for Specifications for Ship and Motor Boat Bells Specifications for Ship and Motor Boat Bells

- Sports in the Navy: 1775 to 1963

- Stalin's Cold War Military Machine: A New Evaluation

- Statement Regarding Winds Message

- The Story Of The Confederate States' Ship Virginia

- Strait Comparison: Lessons Learned from the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign

- Strategic Concepts of the U.S. Navy (NWP 1 A)

- Striking the Flag

- Structural Repairs in Forward Areas During WWII

- Study of the General Board of the U.S. Navy, 1929-1933

- Submarine Activities Connected with Guerrilla Organizations

- Expand navigation for Submarine Sighting Guide ONI 31-2A Submarine Sighting Guide ONI 31-2A

- Submarine Sighting Guide ONI 31SS-Rev. 1

- Submarine Silhouette Book No. 1

- Submarine Turtle Naval Documents

- Surprised at Tet: U.S. Naval Forces in Vietnam, 1968

- Survey of the Amazon- Selfridge

- Survival of the Collection of the Navy Department Library

- Syria's Chemical Weapons: Issues for Congress

- Expand navigation for T T

- Tactical Lessons of Midway

- Target Information From CIC [Combat Information Center]

- Expand navigation for Terminology and Nomenclature Terminology and Nomenclature

- Terrorism in Southeast Asia

- Terrorism: Some Legal Restrictions on Military Assistance

- Tet: The Turning Point in Vietnam

- This is Ann - Malaria

- Time of Change: National Strategy in the Early Postwar Era

- Titanic Disaster: Report of Navy Hydrographic Office

- Tokyo a Study in Jap Flak Defense

- Tokyo Bay: The Formal Surrender of the Empire of Japan

- Expand navigation for Tonkin Gulf Crisis Tonkin Gulf Crisis

- Tonkin Gulf Crisis, August 1964 - Summary

- Formerly Classified Documents from 2 August - 4 August 1964

- Formerly Classified Documents Subsequent to 4 August 1964

- Publicly Released Information

- Gulf of Tonkin the 1964 Incidents

- Gulf of Tonkin the 1964 Incidents [Part II]

- Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Code Words

- Tonkin Gulf Crisis Select Bibliography

- Torpedo War - Rodgers - Fulton

- Training Ships

- The Trial of Admiral Doenitz

- Tsunami (Tidal Wave) Disasters

- 20th Century Warriors: Native American Participation in the United States Military

- Typhoons and Hurricanes: The Effects of Cyclonic Winds on US Naval Operations

- Typhoons and Hurricanes: The Storm at Apia, Samoa, 15-16 March 1889

- Expand navigation for U U

- U-2s, UFOs, and Operation Blue Book

- U-94 Sunk By USN PBY Plane and HMCS Oakville 8-27-42

- U-162 Sunk By HM Ships Pathfinder, Vimy, and Quentin 9-3-42

- U-210 Sunk By HMCS Assiniboine 7-6-42

- U-352 Sunk By U.S.C.G. Icarus 5-9-42

- U-505 Sinking

- U-571, World War II German Submarine

- U-595 Scuttled and Sunk Off Cape Khamis, Algeria 11-14-42

- U-701 Sunk By US Army Attack Bomber No. 9-29-322, Unit 296 B.S. 7-7-42

- U-Boat War in the Caribbean: Opportunities Lost

- Ultra and the Campaign Against U-boats in World War II

- Underwater earthquake disasters and the U.S. Navy

- Uniform Regulations, 1797

- Uniform Regulations, 1802

- Uniform Regulations, 1814

- Uniform Regulations, 1833

- Uniform Regulations, 1841

- Uniform Regulations, 1852

- Expand navigation for Uniform Regulations, 1864 Uniform Regulations, 1864

- General Regulations: Full Dress, Undress, Service Dress

- Coats, Overcoats, Jackets

- Cuff and Sleeve Ornaments

- Pantaloons, Vests

- Part 1: Rear Admiral to Ensign

- Part 2: Engineer Corps

- Part 3: Professors, Secretaries

- Part 4: Medical Corps

- Part 5: Chaplains, Paymasters

- Part 6: Naval Constructors

- Part 7: Regulations for Wearing Shoulder Straps

- Cap and Cap Ornaments

- Straw Hats, Sword and Scabbard, Sword-Belt, Sword-Knot, Buttons, Cravat

- Dress for Petty Officers and Crew

- Uniform Regulations, 1866

- Uniform Regulations, 1869

- Uniform Regulations, Women's Reserve, USNR, 1943

- Expand navigation for Uniforms of the US Navy Uniforms of the US Navy

- Aiguillettes

- Uniform-Buttons

- Chief Petty Officers' Uniforms U.S. Navy

- Cold-Weather/Foul-Weather Wear

- Gas Masks and Breathing Apparatus U.S. Navy Uniform

- Hats/Caps

- Uniform and Dress of the Navy of the Confederate States

- Insignias U.S. Navy Uniform

- Maintenance/Care of Uniforms

- Men's Uniforms

- Pants/Bell-Bottoms

- Personal Appearance

- Seabags

- Navy Seabags

- Shirts/Jumpers

- Shoes

- Swords

- Naval Uniforms, misc.

- Women's Uniforms

- Petty Officer Rating Badge Locations and Eagle Designs

- Uniform Changes

- Historical Surveys of the Evolution of US Navy Uniforms

- Uniform Regulations

- History of US Navy Uniforms, 1776-1981

- Identification Tags ("Dog Tags")

- United States Atlantic Fleet Organization 1942

- United States Pacific Fleet Organization, 1 May 1945

- United States Naval Hospital Ships

- United States Naval Railway Batteries in France

- United States Navy and the Persian Gulf

- United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

- United States Navy's World of Work

- Expand navigation for United States Submarine Losses World War II United States Submarine Losses World War II

- Notes to US Submarine Losses in World War II

- Introduction

- Albacore (SS 218)

- Amberjack (SS 219)

- Argonaut (SS 166)

- Barbel (SS 316)

- Bonefish (SS 223)

- Bullhead (SS 332)

- Capelin (SS 289)

- Cisco (SS 290)

- Corvina (SS 226)

- Darter (SS 227)

- Dorado (SS 248)

- Escolar (SS 294)

- Flier (SS 250)

- Golet (SS 361)

- Grampus (SS 207)

- Grayback (SS 208)

- Grayling (SS 209)

- Grenadier (SS 210)

- Growler (SS 215)

- Grunion (SS 216)

- Gudgeon (SS 211)

- Harder (SS 257)

- Herring (SS 233)

- Kete (SS 369)

- Lagarto (SS 371)

- Perch (SS 176)

- Pickerel (SS 177)

- Pompano (SS 181)

- R-12 (SS 89)

- Robalo (SS 273)

- Runner (SS 275)

- S-26 (SS 131)

- S-27 (SS 132)

- S-28 (SS 133)

- S-36 (SS 141)

- S-39 (SS 144)

- S-44 (SS 155)

- Scamp (SS 277)

- Scorpion (SS 278)

- Sculpin (SS 191)

- Sealion (SS 195)

- Seawolf (SS 197)

- Shark I* (SS 174)

- Shark 2* (SS 314)

- Snook (SS 279)

- Swordfish (SS 193)

- Tang (SS 306)

- Trigger (SS 237)

- Triton (SS 201)

- Trout (SS 202)

- Tullibee (SS 284)

- Wahoo (SS 238)

- German U-Boat Casualties in World War Two

- Italian Submarine Casualties in World War Two

- Japanese Submarine Casualties in World War Two (I and RO Boats)

- Unmanned Vehicles for U.S. Naval Forces: Background and Issues for Congress

- US Democracy Promotion Policy in the Middle East

- US-Greek Naval Relations Begin

- US Marines at Pearl Harbor

- US Mining and Mine Clearance in North Vietnam

- US Naval Detachment in Turkish Waters, 1919-1924

- US Naval Forces in Northern Russia 1918-1919

- US Naval Plans for War with the United Kingdom in the 1890s

- US Naval Port Officers in the Bordeaux Region, 1917-1919

- Expand navigation for US Navy Abbreviations of World War II US Navy Abbreviations of World War II

- Expand navigation for US Navy and Hawaii-A Historical Summary US Navy and Hawaii-A Historical Summary

- US Navy at War Second Official Report

- US Navy at War Final Official Report

- US Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1970-1980)

- US Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1974-2005)

- US Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1981-1990)

- US Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (1991-2000)

- US Navy Capstone Strategies and Concepts (2001-2010)

- US Navy Capstone Strategy, Policy, Vision and Concept Documents

- US Navy Code Words of World War II

- US Navy Congo River Expedition of 1885

- US Navy Forward Deployment 1801-2001

- Expand navigation for US Navy in Desert Shield/Desert Storm US Navy in Desert Shield/Desert Storm

- Executive Summary

- Overview: Desert Storm - The Role of the Navy

- The Gathering Storm

- A Common Goal - Joint Ops

- Bullets, Bandages and Beans - Logistic Ops

- Thunder and Lightning - The war with Iraq

- Epilogue

- Lessons Learned

- Appendix B: Participating Naval Units

- Appendix A: Chronology - August 1990

- Appendix A: Chronology - September 1990

- Appendix A: Chronology - October 1990

- Appendix A: Chronology - November 1990

- Appendix A: Chronology - December 1990

- Appendix A: Chronology - January 1991

- Appendix A: Chronology - January 1991 cont.

- Appendix A: Chronology - February 1991

- Appendix A: Chronology - March 1991

- Appendix A: Chronology - April 1991

- Appendix C: Allied Participation and Contributions

- Appendix D: Aircraft Sortie Count

- Appendix E: Aircraft Readiness Rates

- Appendix F: Aircraft and Personnel Losses

- Appendix G: Naval Gunfire Support

- Appendix H: Surface Warfare

- Appendix I: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

- Appendix K: Sealift

- Appendix L: Airlift

- US Navy in the World (2001-2010)

- Expand navigation for US Navy instruction for the destruction of signal books, 1863 US Navy instruction for the destruction of signal books, 1863

- US Navy Interviewer's Classification Guide

- US Navy Libraries

- US Navy Libraries: Historic Documents

- US Navy Motor Torpedo Boat Operational Losses

- US Navy Nurse Corps General Uniform Instructions, 1917

- US Navy in Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001-2002

- US Navy Personnel in World War II: Service and Casualty Statistics

- US Navy Personnel Strength, 1775 to Present

- US Navy Sailors Operating Ashore as Artillerymen Roth

- US Navy Ships Lost in Selected Storm/Weather Related Incidents

- US Navy Special Operations in the Korean War

- US Navy Submarines Losses, Selected Accidents, and Selected Incidents of Damage Resulting from Enemy Action, Chronological

- US Occupation Assistance: Iraq, Germany and Japan Compared

- US Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934

- US Prisoners of War and Civilian American Citizens Captured

- US Radar: Operational Characteristics of Radar Classified by Tactical Application

- Use of Naval Forces in the Post-War Era

- U.S.S. Colorado BB-45 Diary

- U.S.S. Searaven S.S. 196 4 July 1945

- Expand navigation for USS Constitution's Battle Record USS Constitution's Battle Record

- USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) Memorial Ceremony

- USS Kearsarge Rescues Soviet Soldiers, 1960

- USS Monitor Versus CSS Virginia and the Battle for Hampton Roads

- USS Pirate; Selected documents on the Salvage of USS Pirate and USS Pledge

- USS Vega, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack

- USS West Virgina, Report of Salvage, Pearl Harbor

- The U.S. Navy Enlistment, Instruction, Pay and Advancement

- Expand navigation for V V

- Expand navigation for W W

- Expand navigation for War Damage Reports War Damage Reports

- Destroyer Report - Gunfire, Bomb and Kamikaze Damage

- Destroyer Report - Torpedo and Mine Damage and Loss in Action

- Submarine Report - Vol. 1, War Damage Report No. 58

- Summary of War Damage to U. S. Battleships, Carriers, Cruisers and Destroyers 17 October, 1941 to 7 December, 1942

- USS Birmingham CL62 War Damage Report No. 48

- USS Boise CL47 War Damage Report No. 24

- USS Canberra CA70 War Damage Report No. 54

- USS Capella AK13 & USS Alhena AKA9 War Damage Report No. 27

- USS Chincoteague AVP24 War Damage Report No. 47

- USS Enterprise CV6 War History 1941 - 1945

- USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report No. 56

- USS Helena CL50 War Damage Report No. 43

- USS Honolulu CL48 War Damge Report No. 1

- USS Houston CL81 War Damage Report No. 53

- USS Independence CVL22 & USS Denver CL58 War Damage Report No. 52

- [USS] Joseph Hewes APA22 War Damage Report No. 32

- USS Lexington CV2 War Damage Report No. 16

- USS Liscome Bay CVE56 War Damage Report No. 45

- USS New Orleans CA32 War Damage Report No. 38

- USS North Carolina BB55 War Damage Report No. 61

- USS Northampton CA26 War Damage Report No. 41

- USS O'Brien DD415 War Damage Report No. 28

- USS Princeton CVL23 War Damage Report No. 62

- USS Quincy CA39, Astoria CA34 & Vincennes CA44 War Damage Report No. 29

- USS San Francisco CA38 War Damage Report No. 26

- USS Saratoga CV3 War Damage Report No. 19

- USS South Dakota BB57 War Damage Report No. 57

- War Instructions United States Navy 1944

- Wardroom NavPers 10002-A

- Wartime Diversion of US Navy Forces in Response to Public Demands for Augmented Coastal Defense-CNA

- Wartime Instructions for United States Merchant Vessels 1942

- Washington Navy Yard: History of the Naval Gun Factory, 1883-1939

- Washington Navy Yard - Pay Roll of Mechanics and Labourers, c1819-1820

- WAVE QUARTERS D STATION RULES FOR LIFE AT D

- WAVE QTRS. D

- Expand navigation for [UPDATED] Washington Navy Yard Station Log November 1822 - December 1889 [UPDATED] Washington Navy Yard Station Log November 1822 - December 1889

- We Will Stand in Viet-Nam

- Who Will Do What With What

- Expand navigation for Why is the Colonel Called "Kernal"? Why is the Colonel Called "Kernal"?

- With a View to Publication

- Women in the Navy

- Women's Uniform Regulations, Yeoman (F), US Naval Reserve Force, 1918

- Women's Winter Uniform Regulations, Yeoman (F), US Naval Reserve Force, 1919

- World War I British and German Naval Messages (1918)

- World War II Casualties

- World War II Invasion of Normandy 1944 Interrogation of Generalleutnant Rudolf Schmetzer

- What is CORDS

- Expand navigation for War Damage Reports War Damage Reports

- X

- Expand navigation for Y Y

- Expand navigation for Z Z

- Expand navigation for List of Z-grams List of Z-grams

- Z-Gram 1

- Z-Gram 2

- Z-Gram 3

- Z-Gram 4

- Z-Gram 5

- Z-Gram 6

- Z-Gram 7

- Z-Gram 8

- Z-Gram 9

- Z-Gram 10

- Z-Gram 11

- Z-Gram 12

- Z-Gram 13

- Z-Gram 14

- Z-Gram 15

- Z-Gram 16

- Z-Gram 17

- Z-Gram 18

- Z-Gram 19

- Z-Gram 20

- Z-Gram 21

- Z-Gram 22

- Z-Gram 23

- Z-Gram 24

- Z-Gram 25

- Z-gram 26

- Z-Gram 27

- Z-Gram 28

- Z-Gram 29

- Z-Gram 30

- Z-Gram 31

- Z-Gram 32

- Z-Gram 33

- Z-Gram 34

- Z-Gram 35

- Z-Gram 36

- Z-Gram 37

- Z-Gram 38

- Z-Gram 39

- Z-Gram 40

- Z-Gram 41

- Z-Gram 42

- Z-Gram 43

- Z-Gram 44

- Z-Gram 45

- Z-Gram 46

- Z-Gram 47

- Z-Gram 48

- Z-Gram 49

- Z-Gram 50

- Z-Gram 51

- Z-Gram 52

- Z-Gram 53

- Z-Gram 54

- Z-Gram 55

- Z-Gram 56

- Z-Gram 57

- Z-Gram 58

- Z-Gram 59

- Z-Gram 60

- Z-Gram 61

- Z-Gram 62

- Z-Gram 63

- Z-Gram 64

- Z-Gram 65

- Z-Gram 66

- Z-Gram 67

- Z-Gram 68

- Z-Gram 69

- Z-Gram 70

- Z-Gram 71

- Z-Gram 72

- Z-Gram 73

- Z-Gram 74

- Z-Gram 75

- Z-Gram 76

- Z-Gram 77

- Z-Gram 78

- Z-Gram 79

- Z-Gram 80

- Z-Gram 81

- Z-Gram 82

- Z-Gram 83

- Z-Gram 84

- Z-Gram 85

- Z-Gram 86

- Z-Gram 87

- Z-Gram 88

- Z-Gram 89

- Z-Gram 90

- Z-Gram 91

- Z-Gram 92

- Z-Gram 93

- Z-Gram 94

- Z-Gram 95

- Z-Gram 96

- Z-Gram 97

- Z-Gram 98

- Z-Gram 99

- Z-Gram 100

- Z-Gram 101

- Z-Gram 102

- Z-Gram 103

- Z-Gram 104

- Z-Gram 105

- Z-Gram 106

- Z-Gram 107

- Z-Gram 108

- Z-Gram 109

- Z-Gram 110

- Z-Gram 111

- Z-Gram 112

- Z-Gram 113

- Z-Gram 114

- Z-Gram 115

- Z-Gram 116

- Z-Gram 117

- Z-Gram 118

- Z-Gram 119

- Z-Gram 120

- Z-Gram 121

- Z-grams: A List of Policy Directives Issued by Admiral Zumwalt

- Expand navigation for List of Z-grams List of Z-grams

- People--African Americans

- Letter

- Publication

- Image (gif, jpg, tiff)

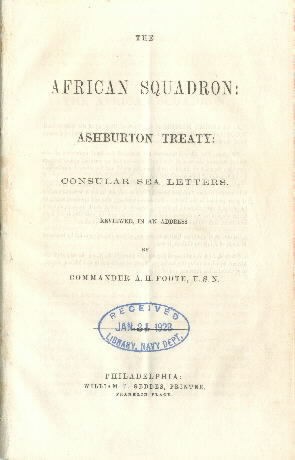

African Squadron:

Ashburton Treaty: Consular Letters.

Reviewed, in an Address

by

Commander A. H. Foote, U.S.N.

Philadelphia:

William F. Geddes, Printer,

Franklin Place.

2

At the ANNUAL MEETING of the Board of Directors of the AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY held in Washington City on the 18th of January 1855, the following preamble and resolutions were adopted viz:

WHEREAS, the African Squadron has protected the legal commerce of the United States on the coast of that Continent — has had an essential agency towards removing the guilt of the slave trade from the world, and has afforded countenance to the Republic of Liberia: — Therefore

Resolved, that no article of the Webster Ashburton Treaty, ought to be abrogated; nor the African Squadron be withdrawn or reduced, unless it be in the number of guns specified in the Treaty. But on the contrary, that said squadron, ought to be rendered more efficient, by the employment of several small steamers, as being better adapted for the suppression of the slave traffic and the protection of our legal commerce, than the mere sailing vessels now composing the squadron.

On motion of the Hon. Dudley S. Gregory, of New Jersey, seconded by President Maclean of Princeton College, it was

Resolved, that the address of Commander Foote, U.S.N. on the subject of the African Squadron under the Ashburton Treaty be published in the African Repository, Colonization Journals, and other papers.

3

The African Squadron,

Mr. President:

Agreeably to the request of the Board of Directors, I will now express my views in reference to the recent action of the U.S. Senate on the subject of the African Squadron and the African Slave trade.

I have before me a copy of the Instructions for the Senior officer of H.B. Majesty's cruisers, on the west coast of Africa, in relation to the treaty of Washington. — "By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great Britain and Ireland, &c." — which say:

"The Commanding officers of her majesty's ship on the African Station, will bear in mind that it is no part of their duty to capture or visit, or in any way to interfere with vessels of the United States, whether these vessels shall have slaves on board or not."

These Instructions show that, as the African slave trade has been pronounced by the United States piracy only in a municipal sense — not piracy by the law of nations, bona fide American vessels, irrespective of their character, are considered by the British Government as well as our own to be in no sense amenable to foreign cruisers. But how is American nationality to be ascertained; for the slaver, even if not American, can easily hoist the American Flag; and therefore, unless the vessel is boarded, our colors may be made to cover the most atrocious acts of piracy. — The 8th article of the Washington Treaty, which the committee of the Senate on Foreign affairs, in their late report propose to abrogate, provides for the co-operation by joint cruising, of British and

4

American men of war. When this stipulation is carried out, the American cruiser boards all vessels under American colors, which prevents the escape of the slaver even under any nationality, for if she is not American the British cruiser captures her. If on the other hand the Treaty be abrogated, no co-operation by joint cruising, between the two squadrons will take place, and British cruisers then will board vessels under the American Flag, to the detriment of our legal commerce, on suspicion of their having assumed false nationality. This practice cannot be conceded as a right. It conflicts with our doctrine of the inviolability of American vessels; and in case the vessel should prove to be by her register or sea-letter American, as her colors indicated, the foreign boarding officer may be regarded in the light of a trespasser; although, if the vessel be, as suspected, a foreigner, she becomes a prize to the British cruiser, for the United States gives no immunity to its Flag when fraudulently used by a vessel of another Nation.

The American Flag has become deeply involved in the slave traffic. Of this as you are aware, from the reports of our officers on the African and Brazil stations and from our diplomatic agents in Rio de Janeiro, there is abundant evidence in the Navy and State Departments. To correct this abuse, and with the design more effectually to suppress the slave trade, Senator Clayton, at the last session, introduced a bill denying consular sea-letters to American Vessels when sold abroad, provided such vessels were bound to the coast of Africa. This wise and beneficent measure was adopted, the bill passing the Senate unanimously. It is greatly to be deplored that the same bill was not immediately taken up and passed by the House of Representatives.

It may be well here to remark in reference to sea-letters, that on the sale of an American vessel in a foreign port to an American citizen, the register of the vessel, which is her proof of nationality, cannot be transferred with the vessel itself; but a sea-letter, which is merely a transcript of the register and bill of sale with the consular seal appended, is given by the Consul as a substitute for said register for the purpose of nationalizing the vessel.

The greatest abuse of our flag has arisen from the facility with which these consular sea-letters have been obtained. More than two-thirds of the slavers on the African coast claiming American

5

nationality, as may be found in documentary evidence, have been provided with this sea-letter. Or in other words, American vessels when sold abroad, have had their nationality perpetuated by this consular sea-letter for the express purpose of being employed in the African slave trade. And surely, when the evil arising from the issuing of this document becomes as well understood in the House, as it has been in the Senate, it may be supposed, that the bill, denying said sea-letters to African bound vessels, will also be passed unanimously by that body.

On the other hand, to those at all familiar with the cunning devices of the Slaver, it will be manifest that in order to extirpate the slave trade, even with the powerful aid of the Clayton bill suppressing sea-letters, the letter and the spirit of the Washington Treaty must be carried out, and the African Squadron rendered more efficient by substituting two or three small steamers for the larger sailing vessels. No regulation of law about sea-letters, on the sale and transfer of vessels, could repair the mischief that must inevitably follow the abrogation of that Treaty. For many an American merchant who has not scrupled to sell his vessel in Brazil or in the Spanish West Indies, knowing it to be designed for the slave trade, would not hesitate to evade the Clayton bill, were the Treaty abrogated, by sending his vessel fully equipped for the traffic, direct from the United States with her register, (as in the recent cases of the slavers Grey Eagle and Julia Moulton from New York) where she would engage in slaving under a charter party. Such instances are even now occurring, while the sea-letter is proof of nationality; and these will be greatly multiplied when by the withdrawal of sea-letters, a vessel must have a register as a protection against the interference of foreign cruisers. In proof of this view permit me to cite a case in point, which occurred while I was in command of the U.S. Brig Perry on the west coast of Africa:

A British cruiser under the Treaty now proposed to be abrogated, proceeded to Loanda and informed the American officers that the Brig Chatsworth, a suspected slaver, was lying at Ambriz, but she being an American vessel, the British officers could do no more than to report the circumstance to the American cruisers. The Perry immediately sailed for Ambriz, where I, in person, boarded and searched the stranger. An American register, but no sea-letter,

6

was found among her papers. The Chatsworth was seized, and afterwards condemned in Baltimore by the U.S. District Court of Maryland. The owner was tried but acquitted — the vessel having been under a charter party in charge of an Italian Supercargo.

Now this case shows: — 1st. That American vessels, owned in the United States, and sailing with bona fide registers, are engaged in the African slave trade; hence the necessity for an American squadron being continued in full force on that coast, even should the Clayton bill, denying sea-letters to vessels when sold abroad, become a law.

2d. It also shows the importance of the treaty, providing for the co-operation by joint cruising, of American and British men-of-war; — for if the said Treaty had not been in force, the British officer would not have gone in search of an American cruiser to report the Chatsworth — and that vessel would have escaped with a cargo of slaves to Brazil.

I have also before me a copy of the report of the committee (of the Senate) on Foreign Relations, proposing to abrogate the 8th article of the treaty of Washington — providing for maintaining a Naval force on the Coast of Africa, for the suppression of the slave trade.

I respectfully remark on the several points presented in this Report:

1st. "The enormous expense in money, with a lamentable loss of life and destruction of the health of the officers and men employed in that noxious climate." The committee estimate[s] the cost of the African Squadron from $800,000 to 1,000,000 annually. — Whereas, the report of the Secretary of the Navy in the year 1842, estimates the cost at $241,182. This, be it remembered, is the first report made after the Treaty with Great Britain. The document reads:

"It is to be remembered that the obligation assumed by the government to keep a squadron on the Coast of Africa, does not create any absolute necessity for an increase to that amount of our naval force. Vessels already in the Navy will be selected for that service. Of course, the annual cost of repairing said vessels is but a part of the usual and necessary expenditure for the naval service. It is not proposed to increase the Navy, with the particular view of sup-

7

plying this squadron; nor would it be proposed to reduce the Navy if this squadron were not necessary and proper. It is merely a part of the customary and useful employment of our vessels of war.

**********************************