The Navy Department Library

Abolishing the Spirit Rations in the Navy

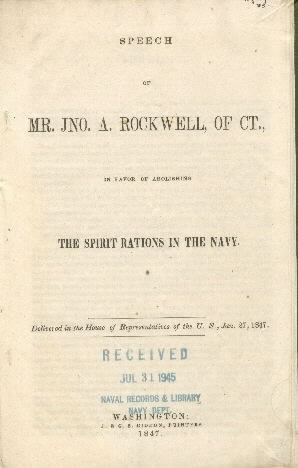

Speech of Mr. Jno. A. Rockwell, of Ct., in Favor of Abolishing the Spirit Rations in the Navy by John Rockwell

SPEECH

OF

MR. JNO. A. ROCKWELL, OF CT.,

IN FAVOR OF ABOLISHING

THE SPIRIT RATIONS IN THE NAVY.

_______________________

Delivered in the House of Representatives of the U.S., Jan 27, 1847.

_______________________

WASHINGTON:

J. & G.S. GIDEON, PRINTERS

1847.

SPEECH

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, January 27, 1847.

Mr. ROCKWELL, of Connecticut, having , on a previous day, offered the following amendment to the Navy Appropriation Bill, viz., "And that, instead of the sum now allowed by law, that the sum of six cents per day be hereafter allowed, and paid in lieu of the Spirit Ration in the Navy, and that said ration be the same as hereby abolished,"; now addressed the House in Committee of the Whole on the State of the Union, as follows:

Mr. CHAIRMAN: I design, in the remarks which I shall address to the House, to abstain entirely from the discussion of any of these important questions which have occupied the attention of the committee, and to confine myself entirely to the examination of the amendment which I have proposed, and the presenting of such facts and arguments as in my judgment conclusively show the importance of its adoption.

The amount now distributed by law is one gill per day of spirits to each seaman, and the persons entitled to receive it can, by the existing laws, receive, in lieu of it, the value of the ration, which does not exceed two cents per day. By the former provision of the law the estimate of the spirit ration was at six cents per day; but instead of that liberal allowance to those who claim to make the commutation, the amount is now too small to furnish an inducement to relinquish the ration. I propose, Mr. Chairman, to show --

1. That there is nothing in the nature of the service performed by seamen in the navy which renders it necessary to furnish them with intoxicating liquors. I am aware that there are strong prejudices on this subject, and a portion of the officers in the navy of great intelligence, and some of them temperate men themselves, claim that, in so severe a service as the seamen in the navy often encounter, spirits are necessary. But sir, I utterly deny this proposition, and will show that such is not, and cannot, be the case, and that in more severe labors, greater exposure and hardships, intoxicating drinks are found not only to be unnecessary, but in the highest degree injurious.

In the merchant service of the United States the regular use of spirits is almost entirely abandoned. The tonnage employed in the commerce of the United States engaged in the foreign trade is 1,095,172 44 ninety-fifths tons, with at least sixty thousand seamen; and it is far within the truth to say, that in four-fifths, if not in nine-tenths, of these vessels, no spirits, or any kind of intoxicating drinks, are furnished as part of the daily rations to the seamen; and many hundreds of vessels sail annually from our ports with no spirits on board, except a small quantity in the medicine chest.

In the coasting trade the change is still more striking. The tonnage of the vessels engaged in this trade is 1,321,829 57 ninety-fifths tons with at least seventy thousand seamen to navigate the vessels. In these vessels the regular supply of spirits is almost entirely abolished, and in a very large proportion of these vessels it is not to be found as an article of drink on board. In addition to the information derived from other sources, I have myself inquired of honorable members of this House, representing the principal commercial points in this country, and they, with one voice, confirm what I have said in relation to the commercial marine of this country, both foreign and coastwise.

But sir, a still more striking result is found in the vessels engaged in

--3--

the whale fishery in this country. This has become, within a few years, a most important branch of the navigating interest of this country. There were, a year since, and the number has since increased, 736 ships, barks, and brigs, owned and sailing from the United States, measuring 223,149 tons, and navigated by 19,560 men - the value of the vessels and catchings being $29,400,000. With this fishery I am somewhat conversant. My honorable friend from the New Bedford district (Mr. GRINNELL) is still more so, as more than three hundred of these vessels are owned in the district so well represented by him here, and he is himself largely interested in that business; and I have no hesitation in asserting that more than nine tenths of the vessels engaged in this fishery from the United States sail without spirits on board; and I appeal to my honorable friend for the correctness of what I have said.

Mr. GRINNELL. The statement is within the truth; and I add my own testimony, not only to the truth of the statement, but to the importance of the result from the abandonment of spirits on board the whale ships.

I have, within a day or two, conversed with an intelligent gentleman, the late collector of port extensively engaged in the whale fishery, who fully confirms the statement which I have made above.

And now, Mr. Chairman, I wish to inquire of gentlemen who are opposed to abolishing this ration, what there is in the naval service which renders spirits necessary or useful, when it is neither the one nor the other in the whale fishery?

It is a well known fact, that although, during a portion of the voyage, the service is no more severe than on board of the national vessels, (and in both the whaling and national vessels sometimes it is less so, owing to the large number of seamen, than in the merchant service and coasting trade,) yet when these whale ships are on their whaling ground, engaged in the catching of the whales, and extracting the oil, there is no more severe, laborious, and hazardous employment on the ocean.

These ships encounter all the storms, the severity of weather, and the other evils and dangers to which the national armed vessels are exposed, and in common with them; but they have, in addition, these dangers, and this hardship, and this labor, so peculiar to themselves.

Nor are these men less resolute, less determined, less competent seamen, less fitted for the discharge of any duty, whether in war or in peace, at home or abroad, than those on board of our national vessels.

There is, probably, not to be found on the face of the globe a body of seamen superior to those nineteen thousand five hundred and sixty men. Do you think, sir, does any man think, that these men would be improved by the daily grog rations; that they would be better men or better sailors; that they would be healthier or more orderly; that they would work or fight better, either with the monsters of the deep or a more civilized foe? I wish, sir, that everyone who thinks so, if there be such a person, would visit, and compare these men with those on board of our national vessels.

I know that some men may honestly have a vague, strange notion, that, in order to have a good sailor in any service, but especially in the naval service, he must be a drinking, swearing, brutal, debased man; and these they call the "old salts" and "old tars," and similar titles. Every person at all acquainted with the subject knows that there could not be a more absurd notion, as it is known, by all experience, to be totally unfounded.

It will be recollected that the number of men in the naval service of the United States is but between 7,000 and 8,000, and those employed in the whale fishery are, in point of numbers, more than double, besides the very large number engaged in the commercial service, both foreign and coastwise; so that

--4--

the most ample experience in relation to those engaged in similar pursuits on the water, and exposed to equal, if not superior, hardships, show that it is not at all necessary in our naval service.

The men themselves engaged in the whale fishery know that it is not necessary. They have an interest in the voyage, being paid by a proportion of the oil and whalebone taken by the vessel; and if it were announced before the sailing of any vessel that the men were to be supplied daily with a gill of grog during all the voyage, no decent man would ship on board of it; and every man, whether drunk or sober, would have sense enough to refuse to take any interest in such a voyage as part owner, officer, or seaman. And if any of my honorable friends, who seem to think that there is a great amount of coercion in not furnishing a daily supply of spirits, should undertake to tell those men that were oppressed by being forced to be temperate, and that the proper way was daily to furnish them with grog, and then set the chaplain to persuade them not to use it, I am inclined to think that they would be told that such doctrine might be very well for the land, but that sailors would not believe it.

I might advert, Mr. Chairman, to the experience which has been furnished us on board steamboats on the inland waters of the country, on railroads, and on various lines of stages. It is now nearly, if not quite, the universal sentiment throughout the country, not only that the lives of passengers should not be hazarded by placing them at the mercy of men of drinking habits, although not actually drunkards, but that the same labors and hardships, to which such persons are often exposed, are better encountered without, than with the use of spirits.

But, Mr. Chairman, these results are not only in accordance with all experience on this subject, but they are precisely such as any one who has examined the matter would anticipate. There in no nourishment in spirits. It is not at any time an article of food. It is nothing but a stimulus, which produces for the moment an unnatural excitement, but which is necessarily attended with a corresponding depression. A person in health is never benefitted by its use. It is a powerful medicine, which physicians unite in ranking as a poison, which, doubtless, may in some diseases be used with advantage, but should be used always with great care, and under the best advice. Its use, instead of giving strength, produces weakness, lassitude, exhaustion. It wears out the system, weakens the powers of the mind, enfeebles the bodily frame. To all this, and more, we have the united testimony of the most able and experienced physicians of the country; and what is far more, we have our own experience; and we all know, who will examine it, that from the very nature and chemical properties of the article, that such must be the result.

I am aware, sir, that it is often said that all this may be very true, but that men who have been in the habit of using it cannot be suddenly broken off without injury to their health, and that therefore it would be a cruel thing to deprive the seamen of the spirits. In the first place, I utterly deny, as a general thing, that it is true that any injury arises from the absolute breaking off of the use of spirits in the most confirmed drinkers. The testimony of experience is all the other way. But if there is a case where, in reforming his drinking habits this may be necessary, a physician is always at hand, who may adopt the course which his health may require. I have far more fear of a surgeon prescribing unnecessarily the use, than any injury from the absolute sudden stopping of the spirits.

I might multiply proofs on the question. The evidence collected in detail, as long ago as 1834, in relation to the use of spirits in the merchant service, by Mr. Delavan, one of the most valuable men of the age, contributed very largely to the disuse of spirits in the merchant service. This testimony was from

--5--

the most experienced merchants and sea captains, and is most ample in its character; and if I print the remarks which I am making, I shall add some of this testimony in detail.

Capt. Edward Gardner, in a letter dated New Bedford, March 8, 1934, says:

"From the experience resulting from ten South Sea voyages in all capacities, from that of a common sailor to commander, I make the following reply: I consider ardent spirits entirely unnecessary and valueless as an anti-scorbutic, under all circumstances, at sea. In passing Cape Horn I have been exposed to wet, cold, and rugged weather, for more than six weeks at a time; on which occasions I have preserved the health of my ship's company by care to keep them provided, as much as was practicable, with a change of dry clothing on going off deck, by giving them plenty to eat, and tea, made hot with ginger, to drink."

Again:

"Having performed five whaling voyages to the Pacific ocean, and procured much of my oil near the equator, on the west coast of Mexico and on Japan, I have never found any occasion, on these or any other voyages, requiring the use of ardent spirits, except as an external application for wounds."

He adds:

"My conviction, as implied in the preceding remarks, is, that distilled spirituous liquors are never necessary for the preservation of sea-faring men, or conducive to their health."

It appears, also, from the testimony of C. Mitchell & Co., of Nantucket, that in 1834 there were 27 out of 77 ships in the whale fishery navigated entirely without ardent spirits on board, the names of which are given; and the letter of Mr. Joseph Rickchen, of New Bedford, in the same year, gives the names, tonnage, and number of men on board, of 186 ships in the whaling business, from New Bedford, of which 168 sailed then without spirits.

You will perceive, sir, that since that time the beneficial results of navigating ships without spirits have led to still greater and almost entire abandonment of ardent spirits in the whale fishery.

2. The government have most wisely, and with the best results, excluded spirits from the rations of the soldiers in the regular service.

The evidence that led to this result was of the very strongest kind, but certainly no more than exists in relation to the navy; and as it is applicable to that branch of the public service, I make a few extracts, in confirmation of what has already been said on this subject:

DESERTIONS FROM THE ARMY IN SEVEN YEARS

| Year. | Number. | Cost. | Trial by Courts-martial. | |

| 1823 | 668 | $58,677 | 1,093 | |

| 1824 | 811 | 70,398 | 1,175 | |

| 1825 | 803 | 67,488 | 1,208 | |

| 1826 | 636 | 54,393 | 1,115 | |

| 1827 | 848 | 61,344 | 991 | |

| 1828 | 820 | 62,137 | 1,476 | |

| 1829 | 1,083 | 96,826 | ||

| Total, | 5,669 | $471,263 | 7,058 | |

(Report of the Secretary of War, February 22, 1830.)

Ardent spirit should be discontinued in the army as a part of the daily rations. I know, from observation and experience, when in the command of the troops, the pernicious effects arising from the practice of regular, daily issues of whiskey. If the recruit joins the service with an uninvited taste, which is not unfrequently the case, the daily privilege and the uniform example soon induce him to taste, and then to drink his allowance. The habit being acquired, he, too, soon becomes a habitual toper." -- (Adjutant General Jones' statement.)

"The proceedings of courts-martial are alone sufficient to prove that the crime of intoxication almost always precedes, and is often the immediate cause of desertion. And I am, moreover, convinced, that most of the soldiers, who enter the army as sober men, acquire habits of intemperance principally by falling into the practice of drinking their gill, or half gill, of whiskey, every morning. I have known sober recruits who often would throw away their morning allowance, but whose constant intercourse with tipplers would soon induce them to taste a

--6--

little, and, in time, a little more, until they became habitual drunkards. I am therefore decidedly of opinion, that the whiskey part of the ration does, slowly, but surely, lead men into those intemperate and vicious habits out of which grow desertions and most other crimes. In support of this opinion, I will only advert to one other document. It is the subjoined extract of a letter from one of the most excellent and exemplary officers of the army, which contains little or nothing more than verbal statements which I have received upon the same subject from many other meritorious officers." -- (Major General Gaines' statement.)

"I have served extensively as the recorder of regimental courts-martial, and do not hesitate to say, that five out of six cases of the crimes which are proved before these courts, have resulted from intemperance; and nine years experience in the army has convinced me, that no inconsiderable portion of the desertions occur in consequence of intemperate drinking, either of the deserters themselves, or others; I say others, because bad treatment from petty officers, while under the influence of ardent spirits, has caused many to become disgusted with the service, and finally to desert.

"I have known cases like the following, and think them not uncommon: A non-commissioned officer, either inebriated or not, oppresses a young soldier, who complains to his commander; the subject is investigated by him; and the witnesses upon whom the complainant relied to sustain his charge, either from fear of the displeasure of their non-commissioned officer, or from being bribed to hold their peace by whiskey, "know nothing." The petty officer produces his witnesses, bought with spirits, to exculpate himself, and perhaps cast blame upon the complainant. The accused, thus cleared, is prompted by revenge to render the situation of the soldier as irksome as possible, who, despairing of redress, deserts."-- (Lieutenant Gallagher's Statement.)

REMARKS BY Dr. WARREN

"The information contained in Dr. Sewall's letter appears to me to be of great importance to the morals and happiness of our country. If the heads of departments and members of congress take an interest in discouraging the use of ardent spirits, the amount of misery which will be prevented, must be great beyond calculation. The suspension of the rations of spirituous liquors to the army is a measure that may be very useful. Its good effects will, I fear, be much dismissed by the permission to sutlers to sell spirits to the soldiery, under permission of an officer. The consequence of this arrangement will be, that some officers will grant this permission, while others will refuse it; and in this discontent will arise, and the most valuable officers in the army become unpopular and obnoxious. The way seems open for a total prohibition; and certainly an order to this effect would greatly increase the efficiency of the army. The opinion of great bodies of physicians, given in the most solemn manner, is unfavorable to the use of spirits; and I cannot find language strong enough to repeat and impress the fact, that these articles do not give strength, but weakness. A momentary flush of power may be excited under their first impulse; but this is soon followed by a moral and physical failure of strength, and loss of that steady, unyielding courage, necessary to the support of a regular engagement."

"The evils of drinking, great as they are, and dreadful in civilian life, are still greater in the army. Many acts which, committed by citizens, would be trifling and venial, would, if committed by soldiers, be of a serious nature, and be visited with instant and severe retribution. Otherwise discipline and subordination would cease.

"A proportion of at least nine-tenths of crimes committed in the army can be safely and certainly traced to excessive drinking; and there is no way, that I can see, of removing this evil entirely, except by legalizing temperance.

"Let Congress pass a law prohibiting, under any circumstance, the issue and sale to the soldier of the smallest quantity of spirit. Such a law might, and probably would, at first, give uneasiness to some confirmed tipplers; but soon it would be cheerfully acquiesced in, because the law would make no invidious distinctions, and all would fare alike. Our army would gradually, though certainly, become temperate, and its moral and religious character be so far improved as to be an honor as well as safeguard to our country."

3. But, sir, we have from the navy itself the highest and strongest evidence on this subject. Every experiment which has been made to persuade the men to abandon their grog, when successful, has been attended with the most beneficial results.

Commodore Joseph Smith has furnished the following statements on this subject:

BUREAU OF SHIPS AND DOCKS

Washington, Jan 28th, 1846.

DEAR SIR: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your note of yesterday, informing me that you had introduced into the House of Representatives an amendment abolishing the spirit ration in the Navy, and substituting an allowance of six cents per day in lieu of it, and asking

--7--

my experience on this subject, especially on my last cruise, how far spirit was abandoned by the seamen, and its effects.

So far as my experience goes, I have found the abandonment of the use of spirit by seamen to be beneficial in all respects, lessening both crime and punishment.

On my last cruise, the ship in which my flag was worn, the frigate Cumberland, with near 500 persons on board, sailed in November, 1843, and returned in November, 1845. The first part of the cruise the men generally drank their grog; by a course of reasoning and discipline they gradually (and voluntarily of course) stopped their liquor, and received the small pittance of two cents per day therefor.

At the end of the year, all but two had relinquished the spirit part of their ration, and those two requested to be transferred to another ship of the squadron. I gratified them. No person remaining who desired to draw his grog, it was pumped off and landed, and the casks filled with good pure water. To the end of the cruise no more spirits were issued. The crew were, so far as I observed, at all times contented and happy. I never heard of a complaint that liquor was in the slightest degree necessary to enable seamen to better endure the hardships and privations of a sailor's life. On the contrary the men were satisfied they were better off in all respects without it.

I do not entertain a doubt that the majority of seamen in our ships of war would gladly see the spirit ration abolished by law, with the liberal compensation you name, to be paid monthly in lieu thereof. This sum would enable them to purchase fruit, milk, and vegetables, whenever they happened to be in port, which would prove both healthful and grateful to them. Whilst a portion of the men receive their liquor, and the grog tub is daily paraded before their eyes, It appears a strong inducement to others to follow the example, who otherwise would not think of it.

Should you not succeed in abolishing the spirit ration, the amount you propose to give in lieu of it, viz., six cents per day, would be a strong motive to the men to stop the grog, and I am sure would do much to diminish the evils produced by its daily use.

I do not assert that all who would thus voluntarily relinquish their spirits would not drink on shore, but I do believe the measure you propose would give general satisfaction, and be productive of a great deal of good.

I am, very truly and respectfully, yours,

JOSEPH SMITH

An officer on board of the Columbia, on this cruise, after being some time at sea, writes:

"I sincerely hope that the rest of the vessels of our navy will follow the noble example set them by the officers and crew of the Columbia; for I am now convinced that the sailors in our navy do not require the spirit part of their rations. Of a crew of over 450 in the Cumberland, the flag ship in the Mediterranean, all but two voluntarily renounced their grog, and these were suffered to depart. A petition was sent to Congress, signed by the commander, many of the officers, and 250 of the ship's company, praying for the abolition of the spirit portion of this navy ration. ' we have satisfied ourselves,' say they, 'from a year's experience of the temperance system on board this ship, that grog is not necessary to the performance of our duties. In point of health, comfort, and happiness, we are infinitely better without it.' 'The ship commanded great respect for her appearance, and the deportment of her officers and crew while in the Mediterranean. Of 1,200 men who were suffered to go on shore, it was reported that only one man was known to get drunk, and none broke his liberty.'

"In 1831, the Secretary of the Navy expressed his conviction that the use which was made of ardent spirits is one of the greatest curses, and declared his intention to recommend a change in regard to it in the navy. And a distinguished officer gave it as his opinion, that nine-tenths of all the difficulties which the officers had with the men arose from the use of ardent spirits; and expressed his strong conviction, from what he had witnessed on board his own ship and others, of the practicability and great utility of entire abstinence throughout the navy."

The evidence connected with and derived from the Exploring Expedition is most full and satisfactory. Charles Wilkes, esq., the commander of the expedition, says:

"In my opinion, there is no need of spirit rations in the navy. This opinion is founded on my own experience while in command of the Exploring Expedition. The duty we had to perform was certainly as arduous, and perhaps more exposed, than any that has occurred in the navy; yet most of it was performed without grog - I have now particular reference to the boat duty, on which they were for weeks together without it."

4. The use of spirits on shipboard is attended with enormous loss of life and property by shipwreck. The number of shipwrecks of United States vessels in 1842 was 380, and 602 lives were lost at sea. In 1844 there were shipwrecked 208 vessels, with the loss of 105 lives. These shipwrecks were not,

--8--

I suppose, in all instances, occasioned by the use of ardent spirits; nor was the diminution in two years to be ascribed wholly to the constant decrease of the consumption of spirits on shipboard. No temperance and caution can entirely guard against the perils of the ocean. The winds and the waves are in the hands of the Almighty; but all agree that the use of spirits greatly aggravates and increases this enormous evil.

A report of the select committee of the British House of Commons affirms that the number of ships and vessels belonging to the United Kingdom, which have been wrecked and lost during six years, amounts to 2,905, worth, with their cargoes, £14,525,000, or $70,101,000. Of 130 of these the entire crews were drowned; and, in addition to these, 3,414 lives were sacrificed. "Among the principal causes of these losses, the committee state drunkenness' and the use of spirits; these leading often to improper and even contradictory orders on the part of officers, sleeping on the lookout or at the helm among the men; occasioning ships to run foul of each other at night; to be taken aback or overpowered by sudden squalls; sinking, upsetting, or getting dismasted for want of proper vigilance in preparing for the danger; or in steering wrong courses, so as to run upon dangers which might otherwise have been avoided."

The report further states "that the happiest effects have resulted from the experiments, tried in the American navy and merchant service, to do with liquor as an article of daily use, there being more than one thousand sail of American vessels, traversing all the seas of the world in every climate, without the use of spirits by either officers or crews; and that the example of British ships sailing from Liverpool on the same plan has been productive of the greatest benefit to the ship-owners, underwriters, merchants, officers, and crews."

These statements present some idea of the enormous amount of property annually lost by shipwreck, and the great destruction of human life in the same manner.

The view taken on this question by underwriters, practical men, as a matter of business, without any reference to other than the pecuniary bearings of the question, is by no means to be disregarded or overlooked.

In 1834 the insurance companies of the city of New York adopted the following resolution, and the same course is pursued in other cities:

"At a meeting of the board of underwriters, held at the office of the American Insurance Company, in the city of New York, on the 2nd of October, 1834, it was

"Resolved, That the different Marine Insurance Companies, in the city of New York, will allow a deduction of five per cent., on the net premiums which may be taken after this date, on all vessels, and on vessels together with the outfits, if on whaling and on sealing voyages, terminating without loss; provided the master and mate make affidavit, after the termination of the risk, that no ardent spirits had been drunk on board the vessel by the officers and crew during the voyage or term for which the vessel and outfits were insured."

Capt. Wilkes remarks "the destruction of public property, owing to the use of spirits, is immense; and, as a measure of economy as well as safety for the lives and property, I would urge its total exclusion."

I am sure, sir, I need not add testimony on this subject to show that, as a mere question of money--of pecuniary loss by shipwreck alone--the Government suffers annually most severe loss by the continuance of the drinking habits on board their armed ships. To all who are acquainted with that subject no proof beyond their own experience and observation is necessary.

But, Mr. Chairman, there is a more important consideration than even this of pecuniary loss. This constant use of intoxicating drinks leads to the great increase of sickness and death in our navy, especially in the warm climates. It is everywhere the fruitful source of disease, and nowhere more fatal than among sailors. They are often exposed to the fevers and other destructive maladies of unhealthy regions, which require the strong health and vigorous constitutions

--9--

which only exist in connexion with temperate habits. It is a well known fact that a very large portion of those who fill our naval hospitals are there through the immediate or remote effects of ardent spirits with broken down and ruined constitutions.

We have seen that the use of spirits causes a large portion of the desertions in the army, and the same cause operates to a considerable, although not as great an extent, in the navy, occasioning thereby serious pecuniary loss.

5. There is also, sir, another most serious evil attending the continuance of these rations. They impair the discipline and efficiency of the service, and lead to disobedience of orders, assaults, mutinous conduct, and the various offenses on shipboard, and frequent punishment by the brutal practice of whipping. On this subject, I must refer you at length to the remarks of Commodore Jones, commanding the Pacific squadron in 1844. In his address to the naval forces, in the Pacific, he says:

"There now stand before you six of your comrades, about to receive the wages of transgression. Drunkenness is the excuse offered by five out of the six for the commission of offenses for which, under a vigorous enforcement of the law, the transgressor would forfeit his life. As in the present case, so in all others which occur in the navy, five-sixths of the punishment inflicted can easily be traced to drunkenness.

"It has been said that a man-of-war is a state prison. If that be true, Rum is the jailor. Destroy that, and the shipped man can be free as the commissioned officer. Would you desire such a state of things? You have only to will it, and it must be so. Your country has at last advanced one step towards rescuing the sailor from perpetual degradation to which the too free use of ardent spirits has hitherto consigned him. Congress has passed a law to regulate the navy ration, by which whiskey is reduced one-half, and in lieu thereof tea and coffee are issued. Why did not Congress abolish whiskey from your ration altogether? Only because some loving persons in authority libelled your patriotism and love of country, by saying that 'American sailors would not enter the navy without the allowance of whiskey.' Are you willing to rest under the disgrace of such a charge? I trust not; I believe not. I am not. Liquor is a thief and a murderer--the greatest enemy mankind in general have to contend with, though to sailors he is more unrelenting than any other class of men. Will you not--I earnestly ask the question--lend a hand to conquer this greatest of enemies? There is not a man among you that would not cheerfully follow your officers into the cannon's mouth, though its unerring aim were directed by the stoutest hearts. Will any among you join me in a petition to Congress to abolish whiskey from the navy ration altogether, and not only from the ration, but the cabin, the wardroom, and every other part of the ship, save only the medicine department? Is all well with you at present? If not, strike at the root of evil--remove the cause, and the effects will cease; and as the cause of all your troubles is drunkenness, let us remove that evil, and the anticipated good must and will follow."

There is much other testimony, as strong and decided as this; but I will only call your attention to that of the commander of the Exploring Expedition. He remarks:

"I am satisfied that nine-tenths of the punishments in the navy may be traced to the use of the spirit rations; certainly this was the case in my four years' cruise. And I have reason to believe that, with but few exceptions, all punishments on board our public ships originate in it, either on the side of the officers or men.

"There are more drunkards made at the grog tubs of our ships of war than in any other place in our country, with one hundred times the same population."

So far as I know, on this point, the testimony is all on one side of the question. I have never heard of the first officer in the navy who seriously contended that the grog was not the chief cause of the offences on shipboard, as all men now admit that it is of crimes on shore.

Another most injurious consequence of this practice is, that, as spirits are shut out from the commercial service, both foreign and coastwise, and the fisheries, the cast off, intemperate, worthless sailors, with impaired strength and enfeebled frames, seek the navy as the only place where they can obtain the regular supply of grog. The navy is thus more and more becoming the receptacle of a large number of worthless and refuse seamen. A large portion, too, of the seamen in our navy, at least one-third, are foreigners, who have never been naturalized, and

--10--

who never relinquished, or desired to relinquish, their allegiance to their native country. It becomes Congress to look well into this matter, and not rely upon a reputation acquired in former wars, with an entirely different and superior class of seamen. The most valuable seamen, at all times under all circumstances, are our native seamen. It is a memorable fact, that, on board of one ship during the last war, there were no less than three hundred New England freeholders; and there is no difficulty whatever, at all times, in obtaining the necessary supply of sober, orderly persons, for the crews of the ships of war. We have seen that there are more than twice as many men in the whale fishery as in the navy, besides the very large number in the foreign and coasting trade. It is quite time that the navy should cease to be the receptacle of broken down seamen--the "hospital of incurables."

The result of the habits engendered by this pernicious practice in most ruinous to the poor sailor. I am aware that many thoughtlessly dismiss this consideration with a sneer. They either consider them to be hopelessly given over to vice and destruction, or destitute of the feelings of other men.

They do them gross injustice. If seamen are more vicious than others, it is because they have been almost entirely abandoned by the humane; and not only neglected by the Government, but been tempted by that very Government itself to the formation of vicious habits, and their utter ruin.

I would appeal, Mr. Chairman, to this House, to regard themselves as the guardians, and not the enemies, of the sailors; to protect them, to sustain them, to elevate them; to countenance and encourage the efforts which are made by the wise and merciful to promote good order and good morals among them. They are an unprotected class of men. They are most valuable to the Government, and necessary to sustain its honor and maintain its rights. Any effort for their benefit will be duly appreciated. They are generous, tractable, and easily moved by kindness. Let, then, the sheltering and protecting arm of the Government be extended for their benefit.

But if this is asking too much, if you will do no positive act for their good, I may ask of the House, on their behalf, that you will do no act, the direct effect of which is to the injury of all, and the ruin of a large portion of them. It is especially an outrage for the government to persist in destroying the young men in the service, and bringing ruin upon hundreds of families. I perceive that some around me are inclined to consider this a very light affair. Gentlemen need not be alarmed. I am not now undertaking the herculean task of changing the habit of any of my honorable associates on this floor. What I am proposing is a practicable matter, and I am sure I may ask the assistance of all in arresting the evil of drinking and drunkenness in the navy, so far, at least, as to omit to furnish this poison as a part of their rations, the daily food of seamen.

I have, sir, endeavored to show that the furnishing of spirits to seamen is unnecessary; that it is injurious; that the experience in the merchant service, the coasting trade, the fisheries, the army, and every branch and department of business is against it; that it is attended with great loss of life and property by shipwreck, greatly increases sickness and death, impairs the discipline and efficiency of the service, and leads to most of the offences in the navy; that it is attended with great pecuniary loss to the nation, and irreparable injury to the seamen.

I hope, sir, it will not detract from the force of the facts and arguments which have been presented, if I add, that our accountability in this matter is not simply to our constituents, but that there is a moral responsibility; That it is a question of conscience and duty, addressed to each member of this House; and for the mode in which we meet that question we are individually responsible to the "tribunal of last resort."

--11--

APPENDIX.

The amendment for the entire abolishment of the spirit ration in the navy did not prevail. An important advance, however, was made, by the adoption of an amendment allowing a commutation of six cents a day for the spirit ration. It is believed, that by a persevering effort of the friends of the seamen and the navy, it will, at no distant day, be entirely abolished. In order to aid in so desirable a result, there is added below some striking and valuable facts, a portion of which were referred to in the speech when delivered, and others have been since obtained.

WASHINGTON CITY Feb'y 5th, 1847.

My Dear Sir: Your letter of the 3rd was received this morning. In answer to it, I state, that in my opinion there is no need of spirit rations in the navy; this opinion is founded upon my own experience in command of the Exploring Expedition. The duty we had to perform was certainly as arduous, and, perhaps, more exposed, than any that has occurred in the navy; yet most of it was performed without grog. I have now particular reference to the boat duty, on which they were for weeks together without it; it was a proof to me how little they prized it, for I left it optional for any who desired their grog rations to remain on board; but even those who had been constantly in the habit of taking it, preferred going. In my narrative, I have referred to this, vol. 4, page 331, 1st edition.

The idea of its being necessary, and an article of luxury to "poor Jack." I look upon as preposterous; he is always obliged to drink it under restrictions, and this is absolutely required, in order to prevent any one from getting more than his share.

The best men on board our ships do not draw their spirit ration. I think the way, and amount you propose as a commutation, will induce many to relinquish it that now draw it, from pride.

The class of "Old Tars," who love their grog, have entirely passed away, and their deleterious example, as to grog drinking, on the younger ones has ceased. I am satisfied that nine-tenths of the punishments in the navy may be traced to the use of the spirit ration; certainly this was the case in my four years cruize; and I have reason to believe that, with but few exceptions, all punishment on board our public ships originate in it, either on the side of the officers or men.

There are more drunkards made at the "Grog Tubs" of our ships of war, than in any other place in our country, with an hundred times the population!

The destruction of public property, owing to the use of spirits, is immense; and as a measure of economy, as well as safety for their lives and property, I would urge its total exclusion.

"Grog" renders our navy the receptacle for all broken down drunkards, and the vagabonds of every country, where they are past earning their living by work in other places, and

contrive at last to enter the navy, where they continue so, at the expense, and to the great detriment of the public service. The idea of associating with this class prevents very many young men, who have been well brought up, from serving in our public vessels, and makes a system of discipline in the navy necessary, that is not in unison with the spirit of the age.

I do hope your efforts will be successful in abolishing this poison, which is as deleterious to the good order of the navy, as it is noxious to the health of the men.

I am yours, very respectfully,

CHARLES WILKES.

HON. JOHN A. ROCKWELL, Mem. Ho. Reps

The following letter, from the Rev. John Marsh, the early, persevering, and most efficient friend of temperance, contains many important statements and suggestions:

OFFICE OF THE AM. TEMP. UNION

New York, Feb'y 2, 1847

To JOHN A. ROCKWELL, Esq., Member of Congress.

Dear Sir: I regret that it is not on my power to give as full an answer to your inquiries as the subject demands. Twenty years ago, ardent spirit was a regular part of the rations to seamen, in all coasting ,fishing, whaling, and merchant ships. I suppose it may now be said, that it is with almost entire universality dispensed with. There may be in whaling and fishing, what is termed in the army fatigue duty, in which it is given; but even this I understand to be rare. For about ten years, it may now be said, that American ships have navigated all seas, amid all climes, in all seasons, and on the longest voyages, without ardent spirit; the seamen enjoying better health, enduring more fatigue without complaining, and rendering better subordination and service, than under the old system. The spirit and temper with which the change

--12--

has been received, may be judged of by the zeal with which seamen have engaged in the temperance reformation. More than 60,000 are reported as having voluntarily signed the temperance pledge at various ports on our coast.--one-third of these having united themselves with the New York Mariner's Temperance Society. This society has for years held a weekly temperance meeting, which has been conducted chiefly by captains and sailors, about a thousand annually signing the pledge. An index to the benefit upon the character and habits of the sailor may be found in the fact that, by the sailors, (stopping at the Sailor's Home, a temperance boarding-house,) six thousand dollars were last year deposited in the Saving's Bank. Avoiding the cup, the sailor avoids the snare of her whose house is death, and his mind craves and seeks useful knowledge. "No class of men," says a Report of the Maine Temperance Society, "have been so much benefitted as fishermen--Most of their craft making their cruise without ardent spirit." An old captain reports one hundred seamen restored within his knowledge from desperate drunkenness." Seldom, indeed, I believe it is now never the case, that a ship is detained in our harbors for drunken seamen to recover from their debauch, and with almost entire uniformity do they sail immediately from the wharf in full possession of all their physical and moral powers, with clear heads and sound hearts. The importance of the entire dispensing with the spirit ration has been so deeply felt by the insurance companies, that they have, to a wide extent, returned about 5 per cent, on the premium of insurance on all vessels which, upon the termination of the risk, have given satisfactory evidence that no spirit has been used on the voyage. The result to them and to the ship owners, as well as to the seamen themselves, have been of the most important character. In 1842, 380 vessels and 602 lives were lost at sea; in 1844, only 208 vessels and 105 lives; the difference is attributed, by the editors of the Sailor's Magazine, to the progress of temperance among seamen. A report of a select committee of the British House of Commons affirms, that the number of ships and vessels belonging to the United Kingdom which have been wrecked and lost during six years, amounts to 2,905 - worth, with their cargoes, £14,525,000. Of 130 of these, the entire crews were drowned; and, in addition to these, 3,414 lives were sacrificed. Among the principal causes of these losses, the committee state drunkenness and the use of spirits; these leading often to improper, and even contradictory orders, on the part of officers; sleeping on the lookout, or at the helm, among the men, occasioning the ships to run foul of each other at night; to be taken back or overpowered by sudden squalls; sinking, upsetting, or getting dismasted for want of proper vigilance in preparing for the danger; or in steering wrong courses, so as to run upon dangers which might otherwise have been avoided." The report further states, "that the happiest effects have resulted from the experiments tried in the American navy and merchant service, to do without liquor as an article of daily use, there being more then 1,000 sail of American vessels, traversing all the seas of the world, in every climate, without the use of spirits by either officers or crew; and that the example of British ships sailing from Liverpool on the same plan, has been productive of the greatest benefit to ship-owners, underwriters, merchants, officers, and crews."

In 1831, the Secretary of the Navy expresses his conviction, that the use which is made of ardent spirit is one of the greatest curses, and declared his intention to recommend a change with regard to it in the navy. And a distinguished officer then gave his opinion, that nine-tenths of all difficulties which the officers had with the men, arose from the use of ardent spirits; and expressed his strong conviction, from what he had witnessed on board his own ship and others, of the practicability and great utility of entire abstinence throughout the navy. Numerous petitions have, from time to time, been presented to Congress for entirely abolishing the spirit ration; for the friends of the sailor and the navy have believed it essential to their interest and welfare. Petitions from Rhode Island say, "We believe that by spirit rations many noble sailors are confirmed in intemperate habits, not a few have been made drunkards, and valuable lives lost. It leaves seamen less susceptible of moral instruction; counteracts the influence of naval chaplains; makes the tasks of officers more arduous and difficult, and the rigid execution of severe regulations more necessary, in order to preserve due subordination and discipline; renders the crews less qualified to discharge their duties in protecting our commerce, defending our maritime rights, and, especially, in preserving our ships amidst the rage of elements, and, above all, in fighting the battles in time of war." But while these petitions have failed of success, a great spirit of reform has manifested itself among officers and seamen, and voluntary abstinence from the proffered rations has produced the most favorable results. At one time, 300 seamen, on board of the Ohio, had signed the temperance pledge, and but one gallon was dealt out to the crew. On board the United States razee Independence were 130 members of a Sheet Anchor Temperance Society; some of whom had served 15 or 20 years in the navy, yet but three only were known to violate their pledge. Of 5 and 600 men and boys on board a receiving ship in Boston, only about 50 at one time drew the grog ration allowed by Government. On the 1st of March, 1842, the Columbia left Boston harbor on a cruise; all, from the captain to the smallest boy, pledged to total abstinence. A letter from an officer on board, after being some time at sea, said, "I sincerely hope that the rest of the vessels in our navy will follow the noble example set them by the officers and crew of the Columbia; for I am now convinced, that the sailors in our navy do not require the spirit part of their rations." Of a crew of over 450 in the Cumberland, the flag ship in the Mediterranean, all but two voluntarily renounced their grog, and these were suffered to depart. A petition was sent to Congress, signed by the commander,

--13--

many of the officers, and 250 of the ship's company, praying for the abolition of the spirit portion of the navy ration. "We have satisfied ourselves," say they, "from a year's experience of the temperance system on board this ship, that grog is not necessary to the performance of our duties. In point of health, comfort, and happiness, we are infinitely better without it." The ship commanded great respect for her appearance, and the deportment of her officers and men while in the Mediterranean. Of 1,200 men who were suffered to go on shore, it was reported that only one man was known to get drunk, and not one broke his liberty. On leaving his ship, Lieut. Foote made his men an address on the happy effect of banishing the grog tub, which you will find on page 37 of our last annual report, which I sent to you. "The happy effects witnessed," he says, "in the good order and condition of the ship; in her snugness aloft, and cleanliness below; in her rapid exercise of battery, and no less rapid evolutions of getting under way, furling sails, and, I may now add, of beating, by and large, at sea, as well as in port, every thing which we have met."

It may be supposed by some that the voluntary system is the best, and that officers and seamen should be left to work out the evil among themselves. But it is presumed that in no other case is a known evil left to be cured by the moral virtue and self-denial of men in the navy. Besides, how can reformers ever expect successfully to compete with the overwhelming power of Government? Since the spirit ration is banished from the merchant service, it is a well known fact, avowed by the seamen themselves, that drunken seamen enlist in the navy for the avowed object of getting the spirit portion of the ration. Such can never be expected to come under the influence of the reform while the spirit tub is set out, and will perpetually be corrupting others. Insubordination will always be the consequence. Drinking, insolence, disobedience and punishment, will be the daily round, and even the voluntary reform be spurned as effecting nothing amid such powerful counteracting influences. At a large meeting held at Exeter Hall, London, Admiral Coddington not long since declared, that, in the use of ardent spirits originated nearly all the punishments which took place in the navy. Two seamen on board the U. S. ship Congress write from Rio Janeiro, January 8, 1846: "There is a good deal of flogging on board, and, we believe, that ten out of twelve of the cases are caused by drunkenness. There are a good many temperance men among the crew, and we believe if they were all so we should live like brothers; but as soon as the rum gets among them, they begin to quarrel and fight until the brig brings them up, and then comes the cat. As yet, we have kind words, and have neither of received the lash upon our backs since we joined her. We find no difficulty in avoiding these evils, so long as we abstain from the use of ardent spirits, which we hope to do, by the help of God."

The cause of humanity demands that whipping, that most degrading of all things to the spirit of a man, should cease in civilized society. Why should that which makes it necessary be continued, and continued by one of the most enlightened Governments on the face of the earth?

Commodore Jones, commander-in-chief of the Pacific squadron, in his address in 1844 to the naval forces in the Pacific, said: "There now stand before you six of your comrades, about to receive the wages of transgression. Drunkenness is the excuse offered by five out of six for the commission of offenses for which, under a rigorous enforcement of the law, the transgressor would forfeit his life. As in the present case, so in all others which occur in the navy, five-sixths of the punishment inflicted can easily be traced to drunkenness. It has been said, that a man-of-war is a state prison. If that be true, RUM is the jailor; destroy that, and the shipped man can be as free as the commissioned officer. Would you desire such a state of things? You have only to will it, and it must be so. Your country has at last advanced one step towards rescuing the sailor from perpetual degradation, to which the too free use of ardent spirit has hitherto consigned him. Congress has passed a law to regulate the navy ration, by which whiskey is reduced one-half, and, in lieu thereof, tea and coffee are to be issued. Why did not Congress abolish whiskey from your ration altogether? Only because some loving persons in authority libelled your patriotism and love of country by saying, that 'American sailors would not enter the navy without the allurement of whiskey.' Are you willing to rest under the disgrace of such a charge? I trust not; believe not. For one, I am not. Liquor is a thief and a murderer--the greatest enemy mankind, in general, have to contend with, though to sailors he is more unrelenting than to any other class of men. Will you not--I earnestly ask the question--lend a hand to conquer this greatest of enemies? There is not a man among you who would not, most cheerfully, follow your officers to the cannon's mouth, though its unerring aim were directed by the stoutest hearts. Will any among you join me in a petition to Congress to abolish whiskey from the navy ration altogether; and not only from the ration, but from the cabin, the wardroom, and every other part of the ship, save only the medicine department? Is all well with you at present? If not, strike at once at the root of the evil; remove the cause, and the effects must cease. And as the cause of all your trouble is drunkenness, let us remove that evil, and the anticipated good must, and surely will, follow.

I believe the general wish of the country, and of many leading officers in the navy, is, that the spirit part of the navy ration be abolished. Yea, that it is felt to be disgraceful to us that, at this enlightened period, the manifest cause of insubordination, crime, degradation, temporal and eternal ruin, should be continued in this arm of our national defence without any redeeming quality. Hoping that you may succeed in your object,

I am, sir, your friend and humble servant, JOHN MARSH.

--14--

"Commodore Biddle, who commands the Mediterranean squadron, in a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, states that the whole number of persons in the squadron, exclusive of commissioned and warrant officers, is 1,107, and that 819 have stopped their allowance of spirits; and that on board the sloop-of-war John Adams, not a man draws his grog. And a gentleman from Syracuse writes that not an officer on board draws his rations of spirits; and that there is much zeal among them in their temperance cause. Similar changes have taken place on board other ships. One is now fitting out at Washington, and every man, before he goes aboard of her, voluntarily pledges himself to abstain from the use of ardent spirit, and receives, in lieu of his rations of grog, an equivalent in cash. No man not disposed thus to pledge himself is received. And there can be no doubt that the practice of furnishing ardent spirit by the Government, and thus without benefit, and at a great expense, exciting the men to violate the commands of their officers, tempting them to form intemperate habits, and rendering them unfit for the public service; corrupting their morals, increasing their diseases, shortening their lives, and ruining their souls, will, ere long, in the Navy as well as the Army, be done away. Millions now unite with that member of Congress, who, in addressing the head of the War Department on the subject of Temperance, said, 'It may be quickened by what I trust will be its next great step, the relinquishment, through enlightened and patriotic feelings, of ardent spirits by our gallant army and navy.

"Those who have had experience in both, have officially declared that the greatest difficulties they had to encounter, have arisen from the daily rations of spirit to the soldier or sailor. The physician says that it is not promotive of health, but that it weakens the energies, engenders diseases, and destroys life. Why then should it be given at all to the gallant men who bear our banner upon the land and the wave, and who have the glories of their fathers' past achievements in keeping? The small quantity of ardent spirit allowed creates an appetite for more, and it often happens, in both army and navy, that a month's pay of a man is spent for the means of intoxication. In our little army, of 5,642 men, there have been, it is stated, 5,832 courts martial within five years; of which five-sixths are chargeable to intemperance. Desertion alone has cost the United States $336,616 in five years. Add to this the declension of moral feeling, the disease and premature deaths produced, and what a hideous aggregate does it give of the ravages of intemperance. What has been done, it was right and best to do it gradually. But now strike boldly in unison with the public tone; fulfil its expectation; recommend the entire disuse of spirits, and receive from your countrymen the praise of not being statesmen alone , but statesmen and benefactors. Give us your aid to bring upon men almost the brightness of the world's first morning.'

"A distinguished officer of the army, in a letter to our Secretary, says, 'I am under great obligations to you for the fourth report of the American Temperance Society, and I feel myself highly honored in having been made a member of that truly benevolent institution. When I arrived here, I question whether there were three men who abstained wholly from the use of ardent spirits--now, more than three-fourths of our whole number are members of a Temperance Society, on the principle of entire abstinence. They hold regular meetings once a fortnight, at which one of the number reads an essay or tract on intemperance. The effect has been just what I anticipated--a manifest improvement in the appearance, spirits, and conduct of the soldiers. Instead of the insipid and bloated visage, is now seen the cheerful and healthy countenance--where was wrangling and strife is good humor and playfulness--and insubordination and negligence have given place to cheerful obedience and prompt attention to duty. Not a member of the society, which is of six weeks' standing, has been confined in the guard-house, and such has been its influence even upon others, that but two men of the whole command have been confined since the society was established. I hardly need to add that the offence, in both cases, was intoxication--while, before the society was formed the average number of men confined was three in twenty-four hours; so that there were as many men confined before in one day, as are now confined in six weeks. Since the formation of the society no desertion has occurred; while during the month preceding its formation, five men deserted--I must believe that the difference is mainly to be attributed to the temperance reformation. I am more than ever convinced that were a judicious friend of temperance to visit various military posts, and exert himself in this truly benevolent cause, his efforts would save the Government thousands, and the members of the army from incalculable evils.' "

Testimony of American merchants and sea captains relative to total abstinence on shipboard:

In 1834 Mr. E. C. Delavan, as chairman of the executive committee of the N.Y.S. Temperance Society, addressed a series of twelve queries to merchants and ship-masters in different parts of the country on the use of spirits on shipboard. I am indebted to this distinguished gentleman for a pamphlet containing these resolutions, from which I made some extracts. One of the questions was as follows: Question 7. Is it your opinion that, under any circumstances--of storm, change of climate, a fatiguing service--your crews would endure more, suffer less, or perform greater labor with ardent spirit than without it?

The following are a portion of the answers returned:

One of the owners of the ships America, Mount Vernon, and Congress, of Boston, says:

"I think they would not, under so much fatigue, suffer so much, or perform so much labor, with as without it."

--15--

Capt. David M. Banker, of the ship Vera, replies to the same question in the negative. Also Thatcher Wagoner, an owner of ships Timoleon and Roscius. Mr. Benj. Richardson, in relation to the ships Hecuba and Lion, and the barques Moscow and Rouble, says: "No. They certainly are better without it."

Capt. Walter Crocker, of the China ship Isreal, says: "They will unquestionably be better, in any possible case, without it as a drink." He also adds: "There is much better subordination without spirits; much better health in sickly climes; men are much more peaceable and happy among themselves without spirit."

Captain Richard Gridler answers: "No ill effects have arisen in consequence of stormy weather; it is very rare in stormy weather that coffee or tea cannot be prepared." He also says: "It is not necessary, in any vicissitude of climate, as a drink for health and comfort of sailors." He also states as follows, under date of April 7, 1834:

"I commanded a vessel in the merchant service from the year 1825 to 1832, and during the last four years have adopted the temperance plan on board the vessels which I have mentioned.

"I sailed in the ship Grecian upwards of two years, and had my shipping articles opened in large and legible characters, that no ardent spirit whatever should be allowed on board the ship, as former experience taught me that almost all evils on ship board arose in consequence of rum drinking. From this system I have experienced the most happy effects. I have lost no men by sickness, or any other accident, and, when visiting unhealthy climates, an early attention to the complaints of my crew has restored them to health. On the contrary, in pestilential climates, I have observed that intemperate seamen are generally victims, in consequence of medicine having little or no effect on their constitutions.

"There is no difficulty in managing a sober crew; but all manner of evil is to be dreaded among the intemperate."

Messrs. G. Mitchell & Co., of Nantucket, in relation to the ships Primrose, Maria, Phebe, and Christopher Mitchell, answers: "Certainly not. We know from personal experience, that change of climate or fatigue service is easier endured without ardent spirits than with it. Under date of May 8, 1834, they write:

"We have long been of the opinion that ardent spirit was a useless article on board ship as part of the stores; and in the year 1830 we determined to try the experiment of sending our ships to sea without it; accordingly, we commenced with the ship Phebe, bound into the Pacific. Here is an extract from our instructions to our masters, since we quitted sending spirits in the ships: 'In port, you will take care to allow no smuggling to be carried on from the ship; and also take care that your men do not sell their clothes to buy fruit and liquor. You are at liberty to furnish them with fruit, where it is plenty, at ship's expense; this will save provisions; but you are not at liberty to furnish them with distilled spirits of any kind, nor to allow any to come on board the ship, except in very small quantity, to be used as medicine only. In lieu of spirits you will give your men beer, brewed on board the ship, for which purpose you have an extra quantity of molasses on board.' "

Capt. Edward Richardson, in relation to the ships Poland, Alfred, and Hogarth, answers:

"I am confident, in every case, and in every climate, water is better." He also says: "In every such instance I found spirits injurious; and since I have abandoned the use entirely, about six years, I have found much less sickness on board."

Capt. B.B. Williams, of the Henry Thompson, gives similar answers in the negative.

Messrs. Stanton, Nichols & Whitney, in relation to the ships Martha, Norfolk, Monmouth, and Gasper, answers: "We think they perform more without spirit."

Capt. Samuel Harding, of Brunswick, Maine, commanded a ship 33 years, emphatically answers: "No, no, no."

Mr. William Savage, of Boston, under date of August 7, 1834, writes:

"Seamen now as readily ship for voyages, wherein it is stated, at the head of the shipping paper, No grog, as they do when grog is given, and I think even more readily.

I think it as essential that no spirit should be furnished in the cabin for the officers, as that the men should be without spirits. In the early part of my life I made many voyaged to sea, as supercargo often, and as passenger. I have seen many instances of the ill effects on a master or mate's taking a strong glass of grog; though not absolutely drunkards, it was easy to perceive that a strong glass of grog, and particularly a second one, deprived the officer of a part of his cool judgement. I have seen much evil, but never the least good, from having rum on board; all quarrels at sea have rum for their foundation. It was my own experience of the evil arising from rum that determined me not to furnish my vessels with it; and no sailor has ever refused a voyage, to my knowledge, because rum was not allowed.

"It is about ten years since we began in Boston to put no rum or spirits on board ships as stores. The practice is becoming every day more and more universal, and there is no doubt but that great good has come of this refraining from rum, and it is now almost universally admitted that rum is not necessary."

--16--

[END]