The Navy Department Library

OPERATION OF THE “ADMIRAL SCHEER” IN THE ATLANTIC AND INDIAN OCEANS

23 October, 1940 - 1 April, 1941.

Precis of: Atlantic Kriegfuehrung (Warfare in the Atlantic) PG/36779. War Diaries of the “Admiral Scheer” PG/48430 AND 48433.

OPERATIONS OF THE “ADMIRAL SCHEER” IN THE ATLANTIC AND INDIAN OCEANS.

23 October, 1940 - 1 April, 1941

The “Admiral Scheer”, a pocket-battleship with a displacement of 10,000 tons, belonged to the same class as the “Graf Spee” and the “Deutschland” (later renamed the “Lutzow”). She was built at the Naval Dockyard, Wilhelmshaven, and was launched on 1 April, 1933.

The “Scheer” had a speed of 26 knots, which was made possible by her eight MAN,* 9 cylinder two-stroke engines capable of more than 54,000 H.P., and an action radius of 10,000 miles. Her overall length was 597 feet, with a beam of 71 feet and a fraught of 19 feet. Her armament consisted of six 28 cm. (11”) guns, eight 15.6 cm. (5.9”) guns and six guns as well as ten additional heavy machine guns, two sets of quadruple torpedo tubes, and two “Arado” seaplanes. She carried a complement of 926 officers and ratings. However, some of these armament specifications were subsequently modified.

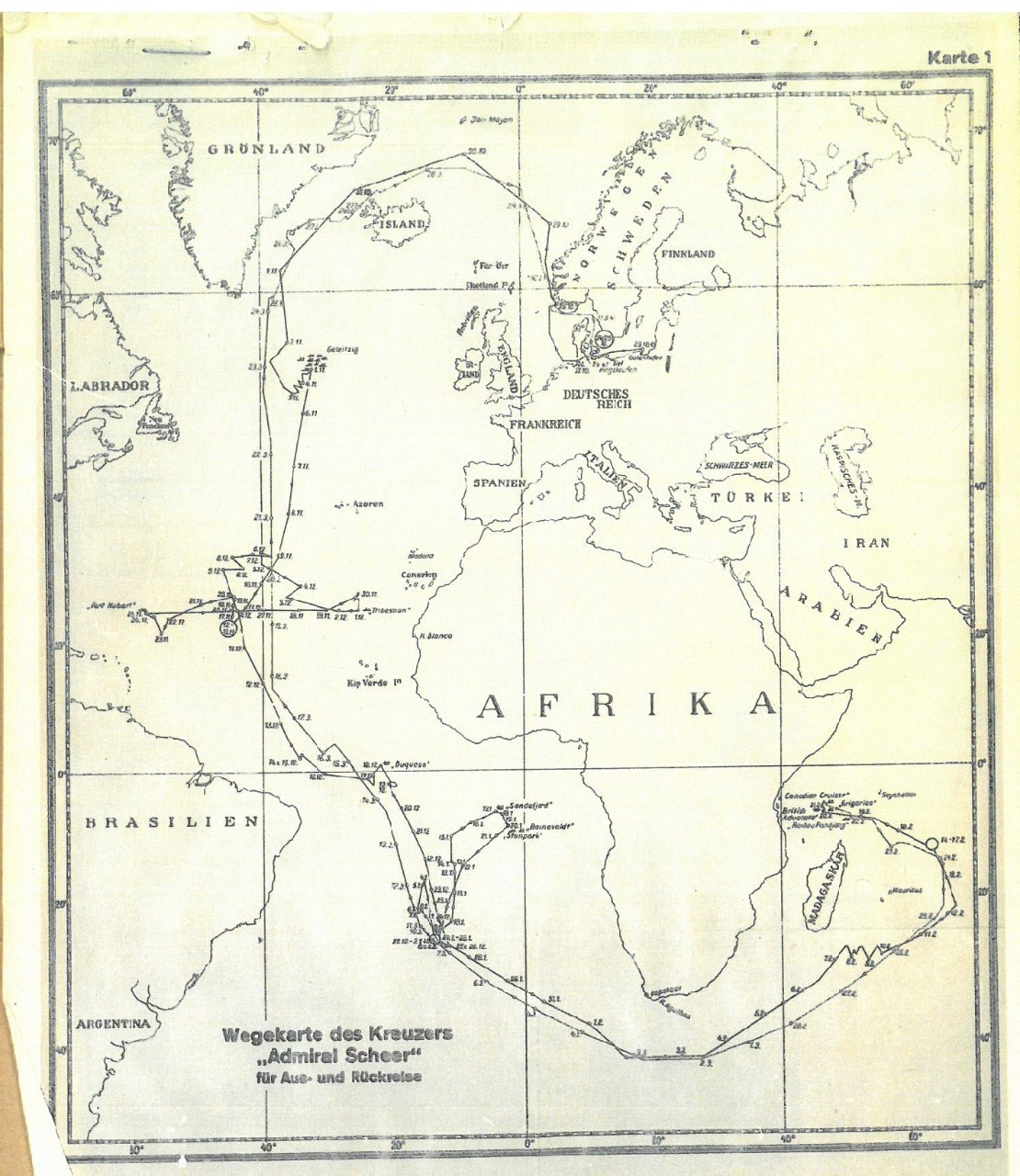

This operation in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans was the “Sheer’s” first great exploit of the war during which she spent 161 days at sea.

A summary of the operational instructions and plan of operation, as drawn up by the German Naval Operations Staff, has been extracted from the German Naval War Staff file “Atlantik Kriegfuehrung” (Warfare in the Atlantic). PG/36779.

“All possible means must be employed to have the “Scheer” in full action readiness by the beginning of September, 1940 and to have all her equipment installed not later than 10 September.”

“The following data and directions have been issued as a guide to the cruise and the plan of operations.”

“The “Scheer” is to put to sea during the first half of September in accordance with the orders issued by the German Naval Group Command, West. It is advisable that she should make her breakthrough into the Atlantic by way of Denmark Strait. The initial attack is planned against the Canadian route, which runs through the central and western area of the North Atlantic. Upon the success of this attack will depend whether a diversion of British naval forces will take place in the North Sea and Channel, this must be accomplished at the earliest possible moment. Therefore, and at all costs, an endeavour must be made to make an unobserved breakthrough into the Atlantic so as to deliver a surprise attack against the North Atlantic convoy route. The “Scheer” will operate on this route, making full use of all available intelligence reports and maintaining a constant guard on the frequencies used by the weakly-escorted Halifax convoys, in order to bring

*MAN: Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nuremberg.

1

about the total destruction of one of these convoys."

“When the “Scheer” has made her first attack the enemy will react vigorously to counter the merchant raider in the Atlantic, so the choice of a second operational area will depend entirely on the enemy’s new disposition of forces.”

“This new operational area will also depend on the position of the sea lanes, their yearly change of traffic concentration or which may even be experienced.”

“A close watch must be kept on the following operational zones: the Canadian route, the West Indies route, especially at their terminals; the north eastern area of the Lesser Antilles and the area around the Azores, where a bunching of traffic is expected. Other areas of interest are the South Atlantic, with the focal point on the Cape=Freetown route and the South American routes, but remaining outside the American Neutrality Zone. Also of importance is the Antarctic during the whaling season (December to March). The Pacific may be considered as an alternative operational area.”

“The commanding officer of the “Scheer” (Captain Krancke) is to make a report on what he estimates to be the earliest date of operational readiness.”

“A further report will follow concerning the rendezvous positions where the “Scheer” will be able to refuel and take on supplies.”

This operational summary was signed by Fricke, Chief of the German Naval Operations Staff.

The “Scheer” was not in full readiness on the date set and the operation was postponed until the second half of October, 1940.

The supply ship “Nordmark” was to supply the “Scheer” with the necessary fuel and other requirements while the supply ship “Dithmarschen” would act as a reserve. The “Nordmark” was to steer clear of all shipping lanes and transmit a daily report to the “Scheer”.

Admiral Doenitz was in charge of the operation.

The narrative which follows has been extracted from the PG/48433 War Diary of the “Admiral Sheer”.

The “Scheer” left Gotenhafen at 0930 on 23 October, 1940, steering through Gjedser Strait. At 1645 on the 25th she entered Kiel-Holtenau. Moving through the Kudensec, she tied up in the inner harbor at Brunsbűttel on the morning of the 26th. She left Brunsbűttel at 1100 on the 27th, in company with three boats of the Second Torpedo Boat Flotilla reaching Stavanger at 0930 on the 28th, where she anchored in the Duscwiki Bight. The same night all four ships put to sea again, steering a general course of 351 degrees. The three torpedo boats were detached when 61 43 N., 03 40 E. had been

2

reached at 0400 on 29 October.

At dusk on the 29th the “Scheer’s” position was 66 27 N., 04 12 E., when course was altered to 300 degrees, speed 18 knots.

A message was received that night from the German Naval Group Command, North, reporting that the “Scheer’s” and “Nordmark’s” breakthrough had remained unobserved, adding that the “Scheer” must take advantage of the situation, for bad weather conditions might be encountered in Denmark Strait on the 30th and 31st.

“The “Scheer” was heading for the Greenland ice barrier, which meant that she would be passing through Denmark Strait either on 31 October or November.”

Her position at midday on the 30th was 69 40 N., 09 35 W., course 255 degrees, having increased her speed earlier to 24 knots. Shortly afterwards bad weather was encountered with the inevitable result that her speed had to be reduced.

At 1300 on the 31st, two echoes, bearing 355 degrees, range 18,400 yards, were picked up by radar. Course was altered to starboard in order to steer clear of what were presumably two patrol craft.

Captain Krancke had decided to steer for 53 00 N., 35 00 W. and to search this area by repeatedly crossing what was presumed to be the Halifax convoy route. The only intelligence available on these convoys was their rate of progress and the dates on which they sailed.

Radio silence was broken for the first time since leaving port at 2316 on 1 November in order to report that the latitude of 60 degrees North had just been crossed. This message concluded the initial stage of the operation, namely the successful breakthrough into the Atlantic.

From the time she had left her home waters, until now, the “Scheer” had remained unobserved from land, sea or air.

The intended patrol area lay between 53 40 N., 35 00 W., and 50 00 N., 36 00 W., doubling back to 52 00 N., 38 00 W. The patrol area was reached by daylight on 3 November.

The task of intercepting a convoy in such a large area without the aid of air reconnaissance (owing to the weather) was quite impracticable. Since the exact route and course of the convoy was not known, this alone meant covering an area 100 miles wide, assuming that the convoy was heading for the northern ports of the Western Approaches. Furthermore, assuming the convoy had left Halifax on 27 October with an average speed of 8½ knots, it would reach the patrol area on 3 November.

Adopting another line of thought, Captain Krancke reasoned that there remained the possibility of the Bermuda and Halifax convoys’ assembling off the Newfoundland Bank, which meant that this combined convoy would not reach the patrol area until a later date.

3

To span the greatest possible area it would be necessary to cross the route twice at a speed of 18 knots, thus eliminating the chance of any good-sized convoy escaping attention. The northern limit of the patrol zone would be reached by nightfall and if the convoy had not been sighted by that time, the “Scheer” would cruise up and down the area, steering in a northeasterly direction. The speed would be decreased to 13 knots, maintaining this speed from dusk till dawn to economize fuel consumption. But as soon as the weather improved the seaplane would be used to increase the possibilities of contacting the convoy.

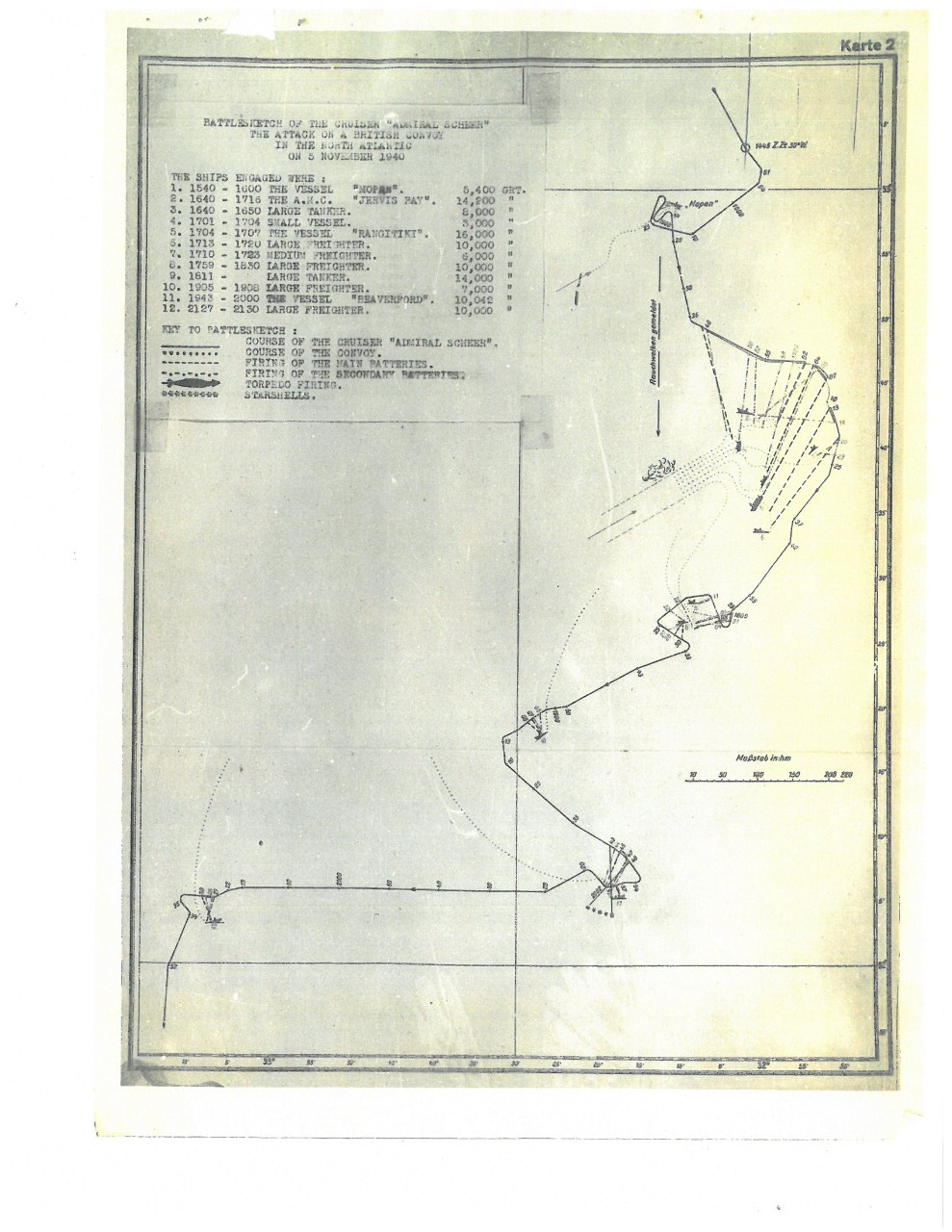

‘Action stations’ was sounded at 0945 on the 3rd when mastheads were sighted on a bearing of 118 degrees. The “Scheer’s” position at the time of sighting was 51 40 N., 37 20 W. At first the “Scheer” turned away but then steered towards until the range had closed to 27,500 yards, when the ship was identified from the foretop. She was a tanker, steering a southwesterly course. To attack the vessel was out of the question, especially since the convoy was expected to put in an appearance at any moment. Course was again altered to 110 degrees, which was the course the “Scheer” had been steering before the sighting.

On the 4th the weather was still unsuitable for air reconnaissance. However, at 1600 that day smoke columns were sighted, bearing 050 degrees, the “Scheer” then being at 52 52 N., 33 39 W.

There was as yet no certainty as to whether these smoke columns originated from one or more vessels, so course was altered to 060 degrees to investigate. The range rapidly decreased and a large vessel of the California (?) -Anchor Line, was identified, steering a southwesterly course. The “Scheer” again steered clear of this ship for the same reason as when the first vessel was sighted.

Meeting this second vessel was sufficient proof that the “Scheer” was in the right position on the route. Apparently, the west to east convoy route had not yet been diverted, although it was known that ships en route to America were running further south of this convoy lane.

At 0620 on the 5th a silhouette was sighted, bearing 034 degrees. Course was altered to port, then steering continued in a southerly direction. Visibility was rapidly increasing so there was very little chance of remaining unobserved. Later on that morning course was altered to 200 degrees.

Captain Krancke had calculated that if the convoy was running late it would reach the patrolled area on 5 November, when the “Scheer” would be situated in the center of the estimated convoy route.

On the 5th the weather was suitable for air reconnaissance. The seaplane was launched at 0940, the pilot having been ordered to make a sweep 100 miles wide and 70 miles deep. When the plane returned at 1205 the observer reported having

4

sighted a convoy consisting of eight ships, probably steaming in line ahead, course east. It’s position was 52 41 N., 32 52 W. No escort was observed although more ships were seen some distance astern of the first group. This mean that the intervening distance between the “Scheer” and the convoy was approximately 90 miles.

Captain Krancke had to decide whether to attack the convoy before nightfall or to shadow it and make an attack at dawn. There were two main factors, however, which had to be considered if the latter course was taken: (a), the convoy would be too close to the Western Approaches and (b), the weather might deteriorate overnight.

It was decided that the convoy would be intercepted before nightfall, even though only two hours of daylight would remain. Accordingly, as soon as the plane had been hoisted aboard, course was set to 150 degrees and speed increased to 23 knots.

An hour before the convoy was expected a single smoke column was observed. Closing with this vessel, a flag was seen being hoisted at the gaff the meaning of which could not be established.

The time was now 1427 (on the 5th), the “Scheer’s” position then being approximately 53 40 N., 31 30 W. Course was maintained, for turning away to eastward was out of the question because of the convoy.

While the range was steadily decreasing, the other vessel’s movements created the impression that she was an armed merchant cruiser stationed ahead or at the flank of the convoy.

Turning towards, ‘action stations’ was sounded. With all guns trained on the vessel she was ordered to heave to.

At 1508 the “Scheer” signaled: “Take to your boats and bring your papers across.” This signal was quickly complied with.

With a view to the expected convoy, no prize crew was sent across, and instead the vessel was sunk with gunfire.

The vessel went down at 1605 after the crew had been taken aboard the “Scheer”. She was the armed steamer “Mopan”, 5,389 GRT, belonging to the shipping firm of Elders & Fyffe, Liverpool.

Valuable time had been wasted sinking this vessel, for already smoke columns and mastheads were seen appearing on the southern horizon. Had it been known that the “Mopan” was only a harmless merchant vessel, no attach would have been made.

At 1630 the “Scheer’s” position was 52 47., 32 32 W. A collision course was selected in such a manner that on sighting the convoy, the “Scheer” would be abeam of it. The ships in the convoy would have greater difficulty in evading such an attack. They would be silhouetted against the

5

Sun and the southeasterly wind would prevent them making use of an effective smokescreen. And if an armed merchant cruiser was with the convoy, the “Scheer” would be directly opposite her. The convoy was approached from dead ahead, making it more difficult for the enemy to identify the ship.

When the range had closed to 27,500 yards, a big liner steaming along in the second column repeatedly signaled the letters “MGA”. Although no reply signal was forthcoming, the convoy still maintained its course. When the range was down to 18,700 yards course was altered with the intent to attack the convoy in the above mentioned fashion.

At 1640 the main battery was ordered to open fire on the armed merchant cruiser (“Jervis Bay”), and the secondary battery was ordered to open fire on a tanker.

It was only after the “Scheer” had opened fire that the merchant cruiser fired red flares, a signal for the convoy to alter course to starboard. The merchant cruiser seemed to have been taken completely off her guard. However, she increased her speed, turned away to port and opened fired. Her fire was poor and very inaccurate. The “Scheer” too, had great difficulty in remaining on target with her main batteries, for the enemy was constantly altering course and speed.

After eight minutes of firing the first hit was scored, which set the merchant cruiser’s bridge on fire. The fire controls must have been destroyed, for she ceased fire.

In the meantime, hits had been scored on the tanker by the secondary batteries. When the tanker had disappeared into a smokescreen, these batteries changed target, opening up on the merchant cruiser. Shortly afterwards the merchant cruiser hove to badly damaged, with fires raging over her whole length.

A smokescreen had been layed by the scattering ships which were observed steering a southerly course. At intervals they would open fire on the “Scheer” with little or no effect. The main batteries then trained left, selecting a 16,000 ton two-funnelled vessel as their next target.

Course was then altered to starboard to close the convoy. After the first few salvoes the large vessel turned hard to starboard, disappearing behind the smokescreen. Only one hit had been scored on the after part of the ship which had now been identified as the “Rangitiki”.

The secondary batteries then temporarily engaged a small armed vessel stationed between the merchant cruiser and the “Rangitiki”. This vessel turned away making smoke. The secondary batteries again opened fire on the merchant cruiser.

Meanwhile, the light was beginning to fail making it impossible to survey the scene of action from the control tower. The fire control party then took up stations on the bridge. At 1711 the main batteries opened fire on the nearest target.

6

When Captain Krancke came on the bridge he observed a target which had so far escaped attention. This particular vessel was steering a northwesterly course. The secondary batteries were trained on to the new target and opened fire. The main batteries had already scored hits, when the vessel disappeared into the smokescreen. Both main and secondary batteries temporarily ceased fire.

The convoy had altered course presumably steering in a southerly direction, so the “Scheer” came round to 215 degrees. Shortly thereafter, two silhouettes of ships steering south were sighted. They were on bearing dead ahead and in order to cut off their retreat course was altered 30 degrees to port. The target which had been engaged by the secondary batteries had been badly damaged and to make certain of its destruction the main batteries fired a few independent salvoes at it.

A few slight alterations of course were necessary to enable the fire control to obtain the bearing, course and speed of the new target. The secondary batteries opened up first, followed by a few independent salvoes from the northernmost of the two vessels, a tanker, turned on to a northerly course, but this movement was followed up. Again the “Scheer’s” guns opened fire and with the first salvo from the main batteries the tanker was hit and burst into flames. The ‘cease fire’ was sounded and course was altered to westward.

The ship which had been the first one to be engaged was still under way in spite of the severe battering it had received. The secondary batteries opened up but the range was too great. Altering the port and steering a southeasterly course in order to close with this vessel, Captain Krancke ordered the main and secondary batteries to fire upon the target which caught fire and have to.

Course was now altered to the southwest. After a while two further silhouettes were sighted dead ahead. Twenty minutes later at approximately 1856 the range had closed to within 3,300 yards. The searchlights were then switched on and guided by this illumination both batteries opened up on the northernmost vessel. The enemy vessel returned the fire, but a moment later she too was ablaze.

The other vessel bearing southeast had tried to escape. She appeared to be running at high speed in a southerly direction. Course was altered to 130 degrees. This time the “Scheer” remained well out of range of the enemy’s gunfire. Star shells were fired to provide the required illumination. The star shells were well placed and at 1945 both batteries engaged the target.

This vessel was apparently the S.S. “Beaverford”, for a signal which was intercepted stated that she was being fired upon. Only small fires were seen aboard her. To make her destruction certain she was sunk with torpedoes.

One third of the heavy caliber ammunition had been expended thus far, and only half of the medium caliber was left. Captain Kranke decided then to break off the engagement,

7

abandoning a further systematic search for the other ships. It should be eight days before the “Nordmark” could supply the “Scheer” with the required ammunition. The remaining ammunition would be a decisive factor if surface forces were encountered.

Leaving the scene of action behind, the “Scheer” proceeded on a westerly course to cover up her true course, in case her movements has been observed by the shipwrecked crews.

Three-quarters of an hour later a silhouette was sighted. Closing on the target, the main batteries opened up first, joined by the secondary batteries when the range had closed to 2,750 yards. A few salvoes were sufficient to set the 9-10,000 ton motor-vessel on fire while she started to sink by the bow. The “Scheer” again closed with the vessel to make certain that she would sink. However, no further action was necessary.

A message was transmitted at 2117 informing the German Naval Operations Staff that thus far 65,000 tons of shipping had been sunk and that the “Scheer” was now heading for point “Zander”.

At 2152, steering course 190 degrees, the “Scheer” left a scattered, devastated convoy behind her.

After this successful surprise attack on the Halifax convoy it was necessary that the “Scheer” should disappear into the wide expanse of the Atlantic for a few weeks in order to keep the enemy guessing. The expected counter-move had to be made first before the “Scheer” could make another appearance. Furthermore, fuel and ammunition were required. The “Nordmark” had to supply “U-65”, “Ship 10” and the “Eurofeld” first, which would take place at point “Green”, and this operation would not be completed until 16 November. The “Nordmark” would then be able to rendezvous with the “Scheer” at point “Zander”.

At 0800 on 6 November a position of 49 12 N., 34 00 W. was reached. Shortly afterwards, a message was received from the German Admiralty congratulating the “Scheer’s” ship’s company. S.O.S. messages had been intercepted from “Rangitiki”, “Cornish City”, “Beaverford” and “Sovav”. Apparently the “Scheer’s” had not yet been received, this course lying in direct line with the rendezvous point. The position then was 33 N., 37 45 W.

A southerly course was maintained until 0900 on the 9th when course was altered to 214 degrees, this course lying in direct line with the rendezvous point. The position then was 33 00 N., 37 45 W.

The tanker “Eurofeld” was sighted at 1218 on the 12th. After recognition signals had been exchanged, both ships joined company.

The captain of the tanker came aboard the “Scheer” to receive written instructions to rendezvous with the “Nordmark”, which should supply the “Eurofeld” with the necessary fuel for “Ship 10”, then return to point “Green” and there supply

8

the "Scheer". (Point "Green" : 22 30 N., 46 30 W.). As soon as supply of the “Scheer” had been completed, Captain Krancke intended using the area inside the grid squares DE, DP, DQ and DF as the “Scheer’s” next operational area. (21-35 degrees North, 36-60 degrees West). Patrolling would commence on 25 November. At a later date the “Scheer” would withdraw to the northern sector of the South Atlantic.

Radio silence was broken for the third time on the night of the 12th when the German Operations Staff was informed that the Scheer’s position was now 22 30 N., 46 30 W. (Point “Green").

The “Eurofeld” would not reach point “Green” until the 17th so the “Scheer could only cruise up and down the position while awaiting her arrival.

In the early hours of the 15th a sailing vessel was sighted on a bearing of 310 degrees. The “Scheer” turned away to starboard, half an hour later heaving to, beam on to the seas.

The “Eurofeld” was first sighted at 0610 on the 16th, while the “Nordmark” hove into sight shortly after mid-day. The swell made it impossible to refuel. Consequently, both supply ships proceeded on a northerly course keeping clear of the trade route, while the “Scheer” remained within visibility range.

At 0800 on the 17th the “Scheer” was in position 23 00 N., 45 30 W., still within sight of both tankers. The “Nordmark” was pumping oil over to the “Eurofeld” which would supply “Ship 10” at a later date.

On the morning of the 18th the “Scheer” started taking on supplies and ammunition. The “Eurofeld” had been detached that morning.

During the night of the 18th two white lights were sighted while the ship was still taking on ammunition. The vessel in question was following the route from Freetown to New York. The closest range recorded was 18,900 yards.

At 0900 on 20 November supply of the “Scheer” had been completed. Tanker and battleship parted company, the “Scheer” steering a course of 250 degrees with a speed of 13 knots. Another message was transmitted at 1100 the same day informing the Operations Staff that the “Scheer” intended to operate in grid square DP. (26 30 N., 53 15 W.). This message not only informed the staff of the “Scheer’s” intentions, but it also meant that the ship was now fully supplied and proceeding towards the Antilles-Azores route.

The British would least expect the appearance of a raider in that area in such close proximity to the North Atlantic convoy routes.

Captain Krancke hoped to bag a few tankers, because of their great importance to the British. It would also pay to attack empty tankers heading for Aruba. If no shipping were

9

found in that area, the “Scheer” would proceed eastwards and operation the Cape Verde-England route. The ship would remain a fortnight in the area of grid square DP.

At 1500 on the 20th a message was received from the Operations Staff informing Captain Krancke that he was free to operate south of 42 degrees South to 20 degrees West. Two Italian submarines operating between Spain and Azores had been notified.

Captain Krancke had not considered operating around the Azores on account of these submarines. However, on completion of the patrol in square DP, the operational zone would be shifted to the area between Cape Verde and the Azores in the vicinity of 25 degrees North, 25 degrees West, where both Freetown-England routes crossed.

Midnight of the 20th brought the “Scheer” to 26 25 N., 47 40 W., course then being 250 degrees.

At midnight on the 22nd the position was 22 22 N. 56 17 W. The patrol up and down the northern sector of grid square DP could commence at right angles to the estimated shipping route. It was hoped that this was the actual route running between England and Gibraltar to Sombrero Passage (Anegada Channel). Not much traffic was expected to move from Trinidad-Barbados in the direction of the Azores, because during the refuelling on the “Scheer” for a whole day on that route not a single vessel had been sighted.

At 1117 on 24 November a smoke trail was sighted, bearing 100 degrees, with the range approximately 44,000 yards. At the time of sighting the “Scheer’s” position was 25 10 N., 58 35 W. Speed was increased to 16 knots, thus gradually decreasing the distance between the two ships.

At first, Captain Krancke remained undecided whether to shadow the vessel until dusk and then make an attack, or not, but she would probably have reached the American Neutrality Zone by that time, especially since she was steering a southwesterly course with a speed of about 14 knots. At 1135 speed was increased to 23 knots, with the “Scheer” steering straight for the target.

The other vessel had apparently sighted the “Scheer”, for at 1217 a radio message was intercepted originated by the S.S. “Port Hobard” in which she reported having contacted a raider, giving the “Scheer’s” exact position. This message could not be ‘jammed’, because a fuse had blown in the transmitter.

At 1235 the “Scheer” signalled “Stop, or I will open fire”, followed by: “Do not use W/T”.

The ship then tried to escape, but a warning shot across her bows brought her to a shop.

The “Port Hobard” was sunk with charges at 1550. She was of 7,500 GRT, en route from London to Auckland, intending to bunker at Curacao. She carried a cargo of general merchandise and five airplanes.

10

The “Scheer” withdrew from the scene of action, steering a course of 090 degrees, speed 18 knots. She was forced to leave the area on account of the enemy sighting report which had been received and repeated by an American coastal radio station. The operational area was to be shifted to the eastern part of the Atlantic, somewhere near the position of 25 degrees North, 25 degrees West. A message to that effect was transmitted on the night of the 25th.

The ”Scheer” maintained her course of 090 degrees until 0800 on 29 November, when her new course became 065 degrees, Her position was then 24 55 N., 30 38 W. When the new patrol area was reached (30th), the weather conditions were unfavorable for the seaplane to fly on reconnaissance.

Steering a course of 235 degrees, the “Scheer” patrolled the narrow operational area at slow speed. At midday on the 30th her position was 27 00 N., 25 30 W. Course was altered to 065 degrees at 0300 on 1 December, when she had reached 26 00 N., 27 30 W.

A radio message received that morning from the Naval Operations Staff indicated that the British Battle Group based at Freetown had put to sea. Other units of the British Home Fleet had left Scapa Flow on 28 November and were heading in the direction of the South Atlantic.

Captain Krancke was not quite certain at the time whether these movements were in connection with the badly damaged battleship “Resolution”, then being moved into British home waters, or whether this was the start of a systematic search for the merchant shipping raiders. In either case it meant that the “Scheer’s” now operational area would be given some special attention, for it was situated along the route the British forces would take. This last radio message and subsequent messages proved Captain Krancke’s theory justified.

At 1137 on 1 December, the “Scheer’s” position then being 26 43 N., 26 08 W., a smoke trail was sighted on a bearing of 104 degrees. In order not to cause any unnecessary alarm, Captain Krancke proposed to shadow the vessel, keeping a constant check on her by radar and intending to launch an attack during the coming night.

At 2045 the “Scheer” had reached 24 30 N., 25 12 W. An attach upon the vessel was imminent. Steering alternating courses with a speed of 23 knots, the “Scheer” commenced to close in on her target.

While the “Scheer” was taking up a suitable position to cross the enemy’s bows, the other vessel suddenly turned towards it, thus frustrating the maneuver.

A shot was fired across her bows, but instead of heaving to she went hard over, manning her guns as she went. The “Scheer” illuminated her stern and fired a salvo with the secondary battery. The other vessel returned the fire with no effect. The “Scheer” then fired three more salvoes scoring several hits. Thereupon the vessel blew off steam

11

while the crew was observed to abandon ship.

A boarding party was sent across which identified the ship as the 6,242 GRT “Tribesman” of the Harrison Line, Liverpool. She was en route from England to India carrying a cargo of general merchandise.

Two lifeboats manned by seven Britishers and 69 Indians were picked up, but a third boat manned by the Captain, the First Officer, the Chief Engineer and 18 other Britishers was missing. They would probably make an attempt to salvage the vessel.

In a matter of a few days the people in the third boat would be rescued and the “Scheer’s” position would become known.

The “Tribesman” was sunk with charges at 0300 on 2 December in position 24 28 N., 25 12 W.

The “Scheer” made off in a westerly direction heading towards her new operational area which lay in position 26 50 N., 34 12 W. It was Captain Krancke’s intention to remain in that busy traffic area for two or three days and then to make rendezvous with the “Nordmark” at “Krebs”.

This patrol was reached at 0800 on the 3rd. By 1800 the westernmost position of the patrol had been reached. Course was then altered to 060 degrees.

At 0800 on the 4th course was again altered to 300 degrees, after the “Scheer” had thoroughly combed the area. Nothing had been sighted. This new course would take the “Scheer” to yet another patrol area which had its focal point in position 30 40 N., 39 37 W. “Ship 21” had reported and confirmed this position to be a shipping lane. Captain Krancke hoped that this was the route taken by British tankers proceeding to the West Indies. The “Scheer” would remain in that area until 8 December.

At 2030 on the 6th a message was received which suggested the practicability of a combined operation of the “Scheer” and “Ship 10”. Captain Krancke had to decide upon the date and place of rendezvous.

Having encountered nothing by 1900 on the 8th, the “Scheer” steered a westerly course along the shipping route until 0700 on the 9th, when course was again altered to 160 degrees, this course being in a direct line with point “Krebs” where the “Nordmark” would supply the “Scheer” with fuel. A message was transmitted informing the Naval Operations Staff that point “Krebs” would be reached on the 14th.

At midnight on the 9th the “Scheer’s” position was 27 20 N., 45 00 W.

The seaplane was launched at 0810 on the 10th and returned from reconnaissance at 1050 with the report that a vessel had been sighted in position 24 10 N., 45 00 W. Course was set towards, but the search was abandoned at 1730 that night when nothing had been sighted. It was later established from an intercepted message that the vessel in question had been the

12

American, S.S. “Colabee”.

At 0800 on the 14th the “Nordmark” was sighted when the “Scheer” at that moment was in position 02 20 N., 35 05 W. Refuelling and provisioning took place during the course of the day.

The “Nordmark” was detached on the morning of the 15th, having been ordered to steer for 13 00 S., 16 00 W. and to wait at point “Lubeck” as from 30 December, when she would send a message to the Naval Operations Staff reporting the orders she had received so that a meeting could be arranged with the prize tanker “Storstadt”.

From 17 to 19 December the “Scheer” operated in the eastern area of grid square FD. This position was situated on the South America-Freetown route. (02 30 N. to 04 00 S., 20 00 W. to 24 00 W.)

At 0715 on the 18th, the seaplane having just returned from a reconnaissance flight, the observer handed in the report that a large vessel had been sighted in position 00 40 N., 23 30 W., making about 14 knots. No definite course had been established, for the ship was steering a zigzag course.

Course was altered to 040 degrees. At 1136 the mastheads were sighted on a bearing of 041 degrees, approximate range 38,500 yards. The “Scheer’s” position was then 00 38 N., 22 50 W.

Shortly after midday a warning shot was fired across the vessel’s bows. Two more warning shots had to be fired before she finally have to. This however did not prevent her from transmitting an “RRR” report which was acknowledged by Freetown.

The ship was the 8,652 GRT “Duquesa” of Liverpool, en route from La Plata to England carrying a cargo of meat and eggs. A prize crew was placed aboard her, having received instructions to rendezvous with the “Nordmark”, whilst the “Scheer” remained within visibility range.

The “Scheer’s” seaplane and been launched on the morning of the 19th, but did not return from its flight. An extensive search was made, but there was no trace of the plane or its crew. Several signals were received, but they gave no indication where it had made an emergency landing. At 1530 that day, the “Scheer” and the “Duquesa” parted company, the latter having been instructed to proceed independently to the rendezvous.

The plane was eventually recovered, undamaged but without gas, at 1950 on the 19th at 02 05 S., 21 30 W.

The “Scheer” then continued her progress in southeasterly direction, intending to catch up with the prize ship by 0900 on the 20th in order to pick up important British mail and some supplies. However, the prize ship did not put in an appearance, so course was altered to 090, the “Scheer” standing up and down the position to await her arrival.

13

At 0940 on the 20th there was still no sign of the “Duquesa”. Captain Krancke reasoned that she had probably taken a different course or had reduced her speed to 8 knots.

However at 1751 that night two mastheads were sighted on a bearing of 120 degrees. It seemed quite possible that these belonged to the “Duquesa”. Nevertheless, she was shadowed and it was not until 2322 that the vessel was finally identified by her silhouette. From then on both ships maintained contact.

At midnight on the 20th the “Scheer’s” position was 08 45 S., 17 50 W., steering course 155 degrees.

Both ships hove to at 0900 on the 21st. The “Scheer” then sent her picket boats across to pick up the mailbags and supplies. This operation was not completed until 1509 when progress was resumed, still maintaining the old course of 155 degrees, speed 13 knots. At midnight they had reached a position of 11 10 S., 16 40 W.

The warnings which British radio stations had been transmitting to merchant shipping made it apparent that the appearance of the “Scheer” and of “U-65” in an almost identical, neighboring sea area had made it impossible for the British to survey the situation with any degree of clarity.

With regard to the combined operation of the “Scheer” and “Ship 10”, Captain Krancke stated:

“I may point out that I cannot promise a close tactical cooperation between the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” for the following reasons:

(1) The armed merchant cruiser would be a hindrance to me on account of her slow speed.

(2) My Presence would rob her of her greatest asset, her camouflage.

(3) If and when the situation should become tense, which is quite likely to happen, I would be forced, in contradiction of sound military precepts, to go to the aid of the merchant cruiser, thus endangering my own ship, which does not conform with generally accepted principles.”

“These points would also arise when cooperating with a U-boat. However, the methods used to counteract a U-boat are different, whereas they are identical for both a cruiser and an armed merchant cruiser.”

“This weakness of cooperation between cruiser and merchant cruiser had already been discussed during a staff conference aboard the “Scheer” before our departure.”

“Consequently I have decided not to operate in close contact with “Ship 10”.”

“I can see promising possibilities only in a detached, more strategic form of cooperation. The appearance of both ships in a neighboring operational area would cause a greater

14

degree of unrest and uncertainty and furthermore if the shipping route is diverted, the enemy shipping would then run straight into our trap.”

Mastheads on bearing 120 degrees were sighted at 0627 on 22 December. After an exchange of recognition signals the ship was identified as the “Nordmark”.

Later that morning the captain of the “Nordmark” came aboard the “Scheer” to hold a conference. He received written orders to the affect that after having taken aboard a supply of meat and eggs from the “Duquesa”, the “Nordmark” would proceed to point “Lübeck” to rendezvous with the prize tanker “Storstadt”.

The prize officer of the “Duquesa” received instructions to proceed to a point situated at 25 00 S., 14 00 W. and to remain there in a waiting position until further orders.

At 0945 on the 22nd the “Scheer” set course on 164 degrees, this course being in the general direction of point “Friedrich” where “Ship 10” would be encountered.

Avoiding action was taken when two mastheads, bearing 157 degrees, were sighted at 0956 on the 24th. The vessel was probably American. The “Scheer” could not afford being sighted now, especially since the rendezvous position was in such close proximity to the American shipping route.

At 1750 on Christmas Eve a message was received announcing the award of 100 Iron Crosses Second Class to the “Scheer’s” ship’s-company.

At 0739 on while the “Sheer” was in position 26 13 S., 12 18 W., mastheads were sighted. These belonged to “Ship 10” and the “Eurofeld”, which, as soon as they had identified the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” were lined up on deck and as they drew closer a threefold “Hurra” went up.

Shortly afterward all three ships have to and the commanding officer of “Ship 10” boarded the “Scheer” to hold a conference with Captain Krancke and to exchange views. The ships were lying close together on account of the Christmas festivities were taking place.

For security reasons no private photographs could be taken of “Ship 10” nor could anyone go aboard her, although her crew was able to pay courtesy visits to the “Scheer”.

That afternoon the signal officer and pilots exchanged notes and discussed past experiences.

The “Scheer” shifted her position 7 miles to westward where she remained for the rest of the night under steam but stopped.

A message was received at 0150 on the 26th originated by the Naval Operations Staff. According to this message, the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” would operate in the South Atlantic

15

until the end of January, 1941. In February, the “Scheer”, together with “Ship 33”, would operate in the Antarctic region, a plan which would depend entirely on how matters progressed. It was possible that a meeting would be arranged of the “Scheer” or the “Nordmark” with the “Alsterufer”. If all went well, the Operations Staff expected the “Scheer” to return to her base at the end of March, 1941 during the phase of the new moon.

The alternative was that the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” would operate in the South Atlantic during the month of January, then further north in February. The “Alsterufer” would be at point “Bayern” to supply both ships. Another operational area would be situated south of 40 degrees north, west of 20 degrees West.

This combined operation of the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” in the South Atlantic until the end of January coincided with the arrangements which had already been made by the commanding officers of these ships.

Captain Krancke could not understand why “Ship 33” was being sent to the Antarctic. A ship of unusual type would soon cause alarm with the effect that the Antarctic would be patrolled or else the whaling fleet would be diverted to another area.

Captain Krancke then decided that both the “Scheer” and “Ship 33” would make a swoop on the Antarctic region at the end of January and remain in the area for some time.

At 0700 on the 26th all three ships were together again.

Later that morning the commanding officer of “Ship 10” boarded the “Scheer” again to be present at a conference. The major points discussed at this conference were first of all the new operational areas. The “Scheer” would operate north of 30 degrees South until 1 February, concentrating her activities mainly on the large grid square FV which encompassed 13 45 S.-50 00 S. and 22 00 E.-00 30 E.

Thus, both ships had sufficient space in which to move around without risk of obstructing their mutual activities, even if they had to take refuge in some other area on account of enemy intervention.

Four weeks’ supplies would be transferred to the “Eurofeld” from the “Nordmark” and the “Duquesa”. She would then be available as a supply ship for “Ship 10”.

The “Duquesa” still had 600 tons of coal aboard, which were insufficient for the homeward journey unless of course a coal ship was taken prize during the next few days, which was very unlikely. The meat and eggs would be used extensively and it was decided that the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” would pick up as many supplies as possible on the 27th.

16

When the “Nordmark” refuelled from the “Storstadt” she would supply her with the necessary provisions and afterwards replenish her stores from the “Duquesa”.

If the “Storstadt” was still in position, Captain Krancke intended to transfer most of the prisoners aboard the “Nordmark” to her and then send her home.

The “Scheer and “Ship 10” would rendezvous some time in January to discuss the situation and their experiences. The rendezvous would only take place if it did not interfere with the operation.

Thus, at 1700 on 26 December both the “Scheer” and “Ship 10”, steering a course of 330 degrees and at a speed of 10 knots, set out to rendezvous with the “Duquesa”. At midnight they had reached a position of 25 525 S., 13 05 W.

At 0533 on the 27th the speed was increased to 11 knots and their new course became 276 degrees. The “Scheer” moved off to port to carry out a range and bearing exercise. This exercise did not commence until 0800, the Scheer’s” course then being 026 degrees, speed 18 knots.

At 0814 mastheads were sighted bearing due North. The mastheads were identified as belonging to the prize ship “Duquesa”.

Course was altered towards, but before the “Scheer” hove to, the seaplane was launched as a safety measure while the ships were lying close to one another.

The boats were called away at 1025 and once more fresh supplies were shipped across from the prize ship. These supplies were especially welcome to “Ship 10”.

The plane alighted at 1140, having nothing to report. Later that afternoon it took off again, this flight too being uneventful.

That night the two warships withdrew in westerly direction, speed 6 knots, the “Scheer” remaining astern of “Ship 10”. Their position at 2000 was 25 00 S., 14 00 W.

Course was altered several times on the morning of the 28th until 0613, when they remained on a course of 050 degrees. By 0747 a position of 25 30 S., 14 00 W. had been reached. The “Scheer” then hove to within visibility range of “Ship 10” and the “Nordmark”.

Painting the ship’s side and scraping to remove the rust was in progress during the forenoon and part of the afternoon. The damaged seaplane float was exchanged for one of “Ship 10’s” reserve floats.

A message from the German Operations Staff was received at 1420 informing the Scheer” that spare radar parts and other spare parts had been dispatched with the “Alsterufer”.

17

At 1650 the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” were under way again, steering course 090, speed 6 knots.

Captain Krancke had decided to maintain that slow speed throughout the night. He also intended, as soon as the “Scheer” had refuelled from the “Nordmark”, i.e. on the morning of the 29th, to set course for position “Lubeck”.

An intercepted radio message received at 1830 revealed that the tanker “Bardiene” had sailed from Freetown on the 25th of December and would arrive at St. Helena on 2 January, 1941. She was transporting oil fuel and gasoline for the British carrier “Hermes”. Captain Krancke was under the impression that the tanker would at that time be somewhere near St. Helena. It would have been a major victory to have captured or destroyed this tanker, but as it happened the “Scheer” was a thousand miles distant from her. The scheme had its possibilities, but the chances of intercepting this particular tanker were very slight, especially since not even her course was known. It also meant that the plan of refuelling from the “Nordmark” would have to be abandoned, which in turn would refuel from the “Storstadt”. Consequently, she would only be able to take on a limited amount of fuel. Captain Krancke therefore decided to abandon the idea of the operation and to carry out his original plans.

The position at midnight was 26 00 S., 13 30 W. Since the “Scheer” had left Gotenhafen, she covered a distance of 19,556 miles.

The “Nordmark” was sighted at 0440 on the 29th. It was not until 0645 that the “Scheer” hove to close to her. Shortly after 0900 the “Scheer” was taken in tow by the “Nordmark” to carry out the refuelling. More supplies were taken aboard together with a load of lubricating oil.

The crew was again employed in painting ship and removing the rust.

At 0925 that morning a radio message from the Naval Operations Staff was received concerning the American Neutrality Zone. The message stated that the Neutrality zone had been extended to a 600 mile limit, instead of the former 300 mile limit. This confused the situation for “Ship 10”. The commanding officer of “Ship 10” had previously stated that the 300 mile limit, as stipulated in his basic orders, had been operationally satisfactory. This meant that the “Scheer” would have to operate in accordance with this latest order. It would prevent the “Scheer” from operating along the South American Coast.

While refuelling was in progress the tow had parted three times and it was not until 1530 that this operation was completed.

At 1829 the “Scheer” set course on 270 degrees with a speed of 16 knots in order to close with “Ship 10”.

The next point on the agenda was to organize a search for the “Storstadt”. That night the “Scheer” would proceed on a course of 120 degrees, “Ship 10” on 160 degrees.

18

Both ships would rendezvous at about 0900 on the following morning, 10 miles south of point “Lűbeck”.

At 0538 on the 30th the lookouts reported a smoke column, ,bearing 254 degrees, presumable originating from “Ship 10”. Two hours later the mastheads of a tanker became visible. They were those of the “Eurofeld”. At 0812 the “Nordmark” came into sight. Half an hour later the “Scheer” closed with “Ship 10” and the “Eurofeld”.

The same morning the commanding officer of “Ship 10” came aboard the “Scheer” to hold a conference. Meanwhile, the individual ships were taking on more supplies.

The “Scheer” parted company with the other ships at 1800. Arrangements had been made to meet at the same place at 0900 on the morning of the 31st. The four ships were together again by 0707 on the 31st. The “Scheer’s” position at 0800 was 26 22 S., 14 00 W.

“Ship 10’s” plane was launched on a reconnaissance flight that morning, only to report that there was still no sign of the “Storstadt.”

The lower deck was cleared at 1845. The crew was mustered on the quarter deck in order to celebrate New Year’s Eve in the appropriate naval fashion. “Ship 10” came alongside. Captain Kȁhler, her commanding officer, passed his message to the “Scheer” over the loudhailer. The ship’s band then played two marches followed by the Fűhrer’s message and that of the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, read by Captain Krancke. As a finale, the band struck up again. The whole affair was quite impressive in the half light.

Shortly afterwards the ships parted company. They used the same procedure as on the previous night.

The following morning on 1 January, 1941, all four vessels were on the spot by 0730.

That morning the “Scheer’s” seaplane was launched on a reconnaissance flight to try and locate the “Storstadt.” On its return shortly after midday there was still no report from, or sign of, the “Storstadt.”

During a conference held aboard the “Scheer” between Captain Krancke and Captain Kȁhler, they came to the conclusion that the “Scheer” would proceed to the “Nordmark” after a leak which the “Scheer” had developed in the steering compartment had been repaired. “Ship 10” would proceed to the “Eurofeld”. Having completed that task, “Ship 10” would carry out a night patrol in an attempt to locate the missing “Storstadt”. Both ships were to rendezvous at 0500 on the 2nd at the same position. The “Scheer” would then make use of her plane which would carry out a dawn patrol. After that, if there was still no news about the “Storstadt”, the “Scheer” would proceed to point “Berta”. From this point on she would continue the search for the “Storstadt.” ”Ship 10” would proceed westward to her

19

operational area. The “Nordmark” would remain at position “Lűbeck”.

Later that day the “Scheer” contacted the “Nordmark”. Captain Krancke went aboard her to give the commanding officer his instructions. At 1900 the “Nordmark” transmitted a radio message for the “Scheer”, saying: “Have not contacted supply ship”. This signal was confirmed by the German radio station Nordeich at 0045 on the 2nd. The “Storstadt” was again ordered by the Operations Staff to proceed to position “Berta” and to arrive at this position between 2 and 4 January.

“Ship 10” was again contacted in the early hours of the 2nd. While diving and underwater welding was in progress aboard the “Scheer”, her plane was again on reconnaissance.

When it returned and there was still nothing to report, both captains reached the decision that “Ship 10” was to proceed forthwith to the “Nordmark”, there to take on further supplies of meat and eggs, then detail the “Eurofeld” to stand by the “Nordmark” at 0700 on the 3rd when she would be provided with four weeks’ supply. Having accomplished that task, “Ship 10” would then proceed towards her operational area.

The “Nordmark” would remain at position “Lűbeck”. Later on the “Storstadt” would be ordered to join her unless, of course, the “Scheer” encountered her in the next day or so. In any case, the “Nordmark” would join the “Duquesa” and take aboard as many provisions as could be handled.

As soon as the underwater repairs were completed, both the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” steamed away to rejoin the “Nordmark.”

Directly after the “Nordmark” had been encountered the captains of Ship 10” and the “Nordmark” came aboard the “Scheer” to hold a conference. This conference had become a necessity since the “Nordmark” had received a radio message which was later received by both the “Scheer” and “Ship 10.”

The context of the message ran as follows: “The Operations Staff presumes the “Storstadt” did not receive message dated 20 December 1940. She is now in position 11 00 S., 17 00 S., (appr.) The “Storstadt” is proceeding to a position 1700 S., 16 00 W. She will presumably be in that position on 4 January. Will be daily in position at 0800, 1200 and 1600 zone time until 8 January. If no contact is made by that time the “Storstadt” will be homeward bound. Join the “Nordmark” if possible. On completion, or in the case of not meeting, report by signal.”

Captain Krancke’s comment on this was that the approximate position given by the Operations Staff must have been a dead reckoning fix and probably nowhere near the “Storstadt’s” actual position. On account of the evasive action she had to take, she might be far down in the “roaring forties” or even quite close to the “Scheer’s” present position. The only manner in which to make sure of her position was to

20

transmit a signal and request her to disclose her whereabouts.

This signal was in fact made at 1916 GMT.

Captain Krancke further remarked that the position given by the Operations Staff was by no means ideal for refuelling, since it was situated in the middle of the American shipping route. The “Scheer” would proceed to keep the rendezvous with the “Storstadt” instead of the “Nordmark”, primarily because she would consume more fuel than the “Scheer” running at high speed.

The following points resulted from the conference.

(1) If the “Storstadt” was not found, the “Nordmark” would proceed to point “Berta” but if the “Scheer” transmitted: “Have found supply ship”, she would then proceed to 2200 S., 1700 W. She would await the “Scheer’s” arrival at this position. If no signal followed she was to make for point “Lűbeck” on 9 January.

(2) If, however, the “Nordmark” encountered the supply ship at point “Berta”, they would both proceed to point “Lűbeck” and make a signal to that effect.

(3) “Ship 10” was to proceed towards the “Eurofeld” and order her to take up position at point “Lűbeck”. “Ship 10” would then proceed to her own rendezvous (point “Lűbeck or 22 S., 17 W.), unless of course the “Storstadt” had been contacted.

(4) The “Scheer” would proceed to 17 00 S., 16 00 W., and would await the “Storstadt’s” arrival there until the night of the 8th or as long as the “Nordmark” had not contacted her. When the “Scheer” encountered the “Storstadt”, she would proceed to 22 00 S., 17 00 W., making a signal to that effect.

(5) If, however, the “Storstadt’s” position was further south the “Scheer” would ask the Operations Staff to make the rendezvous point at “Lűbeck”.

Shortly after 1800 that night the “Scheer” was under way steering a course of 349 degrees and 16 knots. Two hours later she had reached a position of 25 30 S., 14 00 W.

At 2144 the lookouts sighted a silhouette on a bearing of 42 degrees which was eventually identified as that of the prize ship “Duquesa.”

An incoming radio message received at 2255 stated that the Operations Staff had received the signal sent by the “Nordmark”. The “Storstadt” was not to break radio silence. The last order was still valid and would be carried out. The Operations Staff hoped that a meeting would takeplace before 8 January without the aid of radio communication.

The “Scheer’s” position at 0400 on the 3rd was 23 35 S., 14 32 W., steering the same course and speed.

21

A radio message addressed to the “Storstadt” was intercepted at 0500 that morning containing the same orders which had been previously received, ordering her to proceed to 177 00 S., 16 00 W.

The message had been encoded from the supply ship code tables. It took five hours to decypher it. The message itself contained 88 groups.

It was doubtful whether the message had been received correctly and could be decoded, since the “Storstadt” had only one radio operator. Captain Krancke remarked in his War Diary that he himself would have made the signal as brief as possible. Hence, assuming that the “Storstadt” had been unable to decypher the signal, it meant that she would not be encountered. All this involved an unnecessary waste of time and fuel. A short message in which the position was given or even an acknowledging “JJJ” would have been sufficient to enable the “Scheer” to find her whereabouts.

The “Scheer” reached the rendezvous position at 0630 on the 4th . She have to in order to remain in position.

A signal from the Operations Staff received at 1130 stated that it was assumed that the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” had met. It requested that a signal should be made by either ship, stating whether they were operating together.

A suspicious silhouette was sighted at 0410 on the 5th on a bearing of 182 degrees, presumably that of a tanker. The “Scheer” remained within visibility range. At 0451 the agreed recognition signal was made, the tanker firing the appropriate reply. The ship in question was the “Storstadt”. She immediately received the order to steer a course of 190 degrees, while the “Scheer” followed up astern.

A signal went out to the Operations Staff at 536, stating: “Supply ship, yes”. This signal also instructed “Ship 10” and the “Nordmark” to proceed towards the prearranged meeting place, situated at 22 00 S., 17 00 W.

During the course of the forenoon the commanding officer of the “Storstadt” came aboard the “Scheer” to receive further instructions. Apparently the “Storstadt” had been held up by bad weather. She had then been ordered to wait for “Ship 16”. This had caused another week’s delay. Naturally, she had been unable to reach point “Lűbeck in good time. She had been made for point “Berta”, which passed on 2 January, continuing her progress to reach the rendezvous point (17 S., 16 W. ) in accordance with the radio message.

The “Storstadt” had 500 prisoners on board consequently a transfer from the “Nordmark” to her was out of the question. There was also a shortage of food and water aboard her. The prize ship “Duquesa” would once more prove a blessing with her almost inexhaustible supply of meat and eggs.

Once again the German Operations Staff had been confused by the “Scheer’s” last signal. They were under the impression

22

that either the “Scheer” or “Ship 10” had found the “Storstadt.” The meaning of the “yes” they assumed to be the reply to the question whether both ships were operating together. Presumably, they thought that the “Scheer” had already reached her operational area. A signal from the “Scheer” informing them that matters had been delayed on account of repairs and that the new operational area would lie in the grid square GR.

The engine room personnel had been overhauling and testing the engines and this task was finally completed on the 5th. It had taken considerable time due to the fat that the engines had been at three-quarter readiness the whole time.

On the morning of the 6th the “Scheer” carried out a range and bearing exercise with gun drill, the “Storstadt” serving as target.

At 1452 the “Nordmark” was sighted on a bearing of 198 degrees. Later at 1619 a smoke column and mainmast were sighted, bearing 130 degrees. The vessel was closing rapidly and as she drew nearer it was observed that she had a distinct superstructure. The ship signalled, but the signal could not be recognized.

‘Action stations’ was sounded and the “Scheer” altered course to 190 degrees. The “Nordmark” and the “Storstadt” were ordered to make off in northerly direction. Fifteen minutes later the vessel was identified as “Ship 10” only after the recognition signal had been answered correctly.

This incident proved Captain Krancke’s theory concerning the likelihood of a case of mistaken identity, especially if the two ships were to work in close cooperation.

The “Scheer” then closed with the “Nordmark” to commence refuelling. Another meeting was held aboard the “Scheer” later that day to discuss the next steps which had to be taken.

Having supplied the “Scheer” with the required amount of oil fuel, the “Nordmark” would be able to fill up her tanks with practically all the fuel which was left in the “Storstadt’s” tanks. This amount of fuel, together with that of the “Scheer”, would be sufficient to cover a distance of 40,000 miles. The “Eurofeld”, which was then 300 miles away, would receive a percentage of oil fuel from the “Nordmark” because she would serve “Ship 10” as tanker and supply ship.

When the refuelling was completed the “Scheer” withdrew 20 miles to the east where she remained for the night. The “Scheer” rejoined the other three ships at 0547 on the following morning (7 January).

A reconnaissance flight carried out that morning resulted once more in ‘nothing to report’.

A final plan of campaign drawn up that afternoon aboard

23

the “Scheer” between the commanding Officers of all four ships was based on the following decisions:

(1) “Ship 10” would proceed towards her operational area in grid square GR that night.

(2) The “Scheer” would remain with the tankers until after dark on the 8th when she would proceed to her own operational area in grid square FV.

(3) The “Scheer” would probably transmit a signal on the night of the 8th.

(4) As soon as the “Nordmark’ had completed refuelling, the “Storstadt” would be detached when she would be homeward bound. Thirty hours later the “Nordmark” would transmit a signal in order that the Operations Staff might keep a check on the “Storstadt’s” progress. The reason for the delay in transmission was due to the fact that the Operations Staff would be under the impression that refuelling had taken place at 17 00 S., 16 00 W.

(5) The “Nordmark” would then proceed through the “Duquesa’s” position situated 30 miles west of point “Lűbeck”, where she would supply the “Eurofeld” with 1200 tons of fuel and provisions.

(6) Afterwards, the “Nordmark” would take on supplies from the “Duquesa” and prepare her for scuttling. This was necessary, because she was running short of coal. The “Nordmark” would remain in position at point “Lűbeck”.

(7) If the “Storstadt” was captured, the “Nordmark” would proceed to a new rendezvous position, namely 35 00 S., 14 00 W., unless otherwise stated.

(8) All being well, the “Scheer” would return to point “Lűbeck”, on 26 January, if not to the other position.

(9) The “Scheer” would proceed to the Indian Ocean later than a month and in order to avoid encountering “Ship 10”, she would proceed through 10 00 S., 05 00 W. and then alter course to 090 degrees.

(10) As additional precaution, “Ship 10”, when meeting the “Scheer” would first show her starboard, then her port side, broadside on.

(11) All official and private mail of the “Scheer” and of “Ship 10” were transferred to the “Storstadt.”

That night the “Scheer” took up station 20 miles west of the tankers, where she remained until the early hours of the 8th.

The “Scheer” joined the two tankers at 0725. Refuelling was still in progress.

That morning the seaplane made a practice attack with

24

two bombs on a raft measuring 6x6 ft.

The bombs missed the raft by more than 100 yards.

The “Nordmark” reported at 1730 that refuelling would probably be completed an hour later. The report also stated that she would be at point “Lűbeck” on 10 January.

The “Storstadt” had been warned about the presence of a British merchant cruiser in the area between 0-10 degrees South and 10-20 degrees West, enabling her to plot her own course accordingly.

The “Scheer’s” next move was to pick up more supplies from the “Duquesa” and then to proceed to her own operational area. She would not reach this area until the period after the full moon.

At 2217 that night the following signal was transmitted to the Operations Staff: “Overhaul completed, am in full readiness. Shifting operational area west of South Africa, square FV.” Another signal followed at 2317: “Operating independently.

At 2400 the “Scheer’s” position was 22 20 S., 15 27 W. course 148 degrees.

At midday on the 9th the “Scheer” hove to close the prize ship “Duquesa” and took on the supplies. At 1851 course was set on 065 degrees, speed 10 knots.

Another Operations Staff signal was intercepted at 1950 in which the “Scheer” was requested to signal “JJJ” if the staff’s assumption was correct that the “Scheer” and “Ship 10” had met and were now operating independently."

Still steering the same course, the “Scheer” reached a position of 24 40 S., 13 40 W. at 2000 that night.

A radio message received at 2300 gave the “Scheer” the necessary information regarding the British convoy WS 5A which had left England on 20 December. This convoy had been attacked by the “Hipper” on 25 December in position 43 00 N., 24 30 W. The convoy’s estimated speed was 8 knots. In that case it would reach a position of 14 00 S., 00 00 W., on 15 January. It was not expected that it would put into Freetown. Escorts in position off Freetown were presumably the “Devonshire”, “Dorsetshire”, “Shropshire” and two light cruisers, with the carrier “Hermes” as outer long range escort. The “Rodney” and “Furious” were somewhere between Freetown and England. British merchant shipping in area 6B had been warned by the British Admiralty that mines had been sighted on 6 January in position 34 54 S., 18 17 E.

This message served as a warning for Captain Krancke not to operate in square FV. It had been hoped that while the “Scheer” was operating there, the convoy would pass the area without a carrier as an additional escort. The risk seemed too great in spite of the full moon. Accordingly, Captain Krancke decided to concentrate only on single ships along the main shipping routes. The operational area would be shifted

25

to a position further north somewhere in the northern sector of grid square FN (6 degrees South, 5 degrees West). To reach this area, the “Scheer” would steer a course of 010 degrees, commencing at 0800 on the 10th and proceed between St. Helena and Ascension Island. The Operations Staff would be informed of this alteration of plans. The “Scheer” accordingly set out on a course of 010 degrees at 0815 on the 10th.

Another radio signal was received at 1705 that night according to which the German motor vessel “Portland” was leaving Talcahuano in order to supply the “Nordmark” with oil fuel at the end of January or early in February. A meeting would take place at point “Meise”. The prisoners would be transferred to the “Portland.” The “Scheer” was requested to state the number of prisoners.

This request was complied with at 2237, when the signal: “Have 400 prisoners” was transmitted. Twenty minutes later the following signal was made: “Am shifting to square FN.”

By midnight the “Scheer” had reached a position of 21 00 S., 11 30 W. At 1600 on 11 January course was altered to due north and speed decreased to 7 knots. Maintaining this course and speed, the “Scheer” finally hove to at midnight on the 12th.

Before entering the operational zone, a few points had to be considered. The WS 5A convoy would be escorted by the Freetown forces as far as St. Helena and from there Capetown escort forces would take over. The former would be passing grid square FN between 14 and 15 January. Hence it was best not to enter the operational area before 16 January. The visibility range during the full moon period in that area would be approximately 22,000 yards. In order to operate successfully it would be necessary to remain in the present position for at least 36 hours. That position at midnight on the 12th was 14 20 S., 11 00 W.

It was not until midday on the 14th that the “Scheer” was under way again steering north, speed 10 knots. This speed of 10 knots had proved most economical for long trips. It would give the “Scheer” an action radius of 20,500 miles.

At 1215 that day the “Scheer” had covered 21,600 miles since she left Gotenhafen, equivalent to the earth’s circumference.

Course was altered to 060 degrees at 1037 on 15 January. By 1500 the clocks had been advanced one hour, which made the time now Greenwich Mean Time.

The “Scheer’s” position at midnight on the 15th was 09 15 S., 10 00 W.

The seaplane set out twice on a reconnaissance flight during the course of the 16th. Nothing was sighted on either occasion.

It was Captain Krancke’s intention to operate on the direct route between Capetown and Freetown as from the 17th. The course to be steered on that route had been ascertained

26

from an intercepted radio message addressed to the British steamer “Peshawar”. This vessel had been ordered to steer through position “B”, 12 12 S., 0012 E. This position was situated on the direct route. The “Scheer” intended to maintain a course of 135 degrees during the forenoon and afternoon, as far as the weather would allow. The plane would fly on ahead. At night the “Scheer” would steer along the route. Any ships which were sighted would be attacked at night, this being a more favorable method of attack. If at any time “Scheer’s” position was reported she would leave the operational area in spite of orders.

At 0800 on the 17th the “Scheer” altered course to 135 degrees, her position at that time being 06 30 S., 05 30 W.

On the return from its second flight that day the plane damaged its port float.

It was learned from a signal received at 1740 that shipping from La Plata to England would in future probably sail in convoy. This precaution was due to the close cooperation between the “Scheer” and “U-65” in the Freetown area and the appearance of “Ship 10” in the la Plata area.

Another signal received at 2140 gave the information that the “Nordmark” would meet “Ship 41” at point “Andalusia”, where she would pick up U-boat supplies. During the second half of March, the “Nordmark” would supply the U-boat “UA”. Captain Krancke commented that this was just what he had expected. The “Nordmark” would supply other ships as long as possible, regardless of the “Scheer’s” homeward journey.

At midnight on the 17th having reached a position of 08 00 S., 05 00 W., the “Scheer” hauled about onto the reciprocal course of 050 degrees. Course was again altered at 0800 on the following day. This time the “Scheer” steered due south.

At 1024 the “Scheer” was in position 07 30 S., 03 40 W., when a smoke column was sighted on a bearing of 142 degrees. A dead reckoning fix estimated the vessel’s course to be approximately 320 degrees.

It was at first thought that the vessel in question was the British steamer “Peshawar” which had been previously reported by the “Scheer’s” radio intercept service. The target was approached from astern in order to establish her exact course. This course was found to be 020 degrees which within visibility range of the vessel.

A signal intercepted at 1345 supplied the following information: “From Portuguese ship “Colonial” 1303 to Freetown: Arrival 0600 Tuesday, need 200 tons of coal as well as 300 tons of water, require pilot”. This vessel, apparently, was also north of the “Scheer.”

At 1537 the “Scheer” had reached a position of 07 23 S., 04 10 W. The seaplane was launched to make an observation flight. It returned at 1750 with the report that the enemy

27

vessel was a tanker. In landing it damaged its port float and both wings, which put the plane out of action for some time.

The “Scheer” set a collision course at 1924, steering by radar.

At 2017 when the “Scheer’s” position was 06 29 S., 04 25½ W., she opened fire with her four 4.1” guns at a range of 2,400 yards. The shells employed were fitted with adjustable time-fuzes and were set to detonate just above the ridge of the enemy vessel. This was the first time that the rapid fare 4.1” guns had been employed during a night engagement. The proved very effective. They had a greater effect upon enemy morale and had a further advantage over the 6” shells which lay in the fact that when the shell bursts were sufficiently high, they would not destroy the vital parts of the ship.

After the first few salvoes aided by the searchlights, the ‘cease fire’ order was sounded.

The enemy vessel did not man her after 4.7” gun, and did not even use her radio transmitter. A boat with 15 men in it was seen to pull away.

The vessel was then identified as the Norwegian motor tanker “Sandefjord”, 8,038 GRT with a crew of 35, en route from Capetown to Freetown carrying a load of 11,000 tons of crude oil.

In reply to the signal: “Who are you?”, the “Scheer” had answered with “ British man of war”, at the same time displaying the illuminated screen with the words: “Stop wireless”. The “Scheer’s” picket boat which had been swung outboard since dusk hauled away with a boarding party.

On examination it was found that she had only 400 tons of fuel left. She consumed 10-11 tons of fuel daily at a speed of 8-9 knots. At this rate she would be able to reach a port in western France in about 30 days. However, under the prevailing weather conditions further north and including evasive action which would be necessary, the 400 tons of fuel were probably inadequate. The “Sandefjord” could accommodate 200 prisoners.

Captain Krancke decided to put a prize crew aboard and despatch her to point “Lűbeck”, where the “Nordmark” would refuel and provision her. The “Nordmark” would also transfer the 200 prisoners. The “Sandefjord” would rendezvous with the “Nordmark” on the evening of 25 January.

For Security reasons, only the Captain and the Second Officer of the “Sandefjord” remained aboard the “Scheer”. According to the prisoners the attack had come as a complete surprise.

At midnight on the 18th the prize ship was detached, having been ordered to steer a course of 230 degrees, speed 9 knots.

28

Captain Krancke intended operating on the route for a few more days, since the capture of the “Sandefjord” had not become known.

At 0800 on the 19th the long-awaited signal of “Ship 33’s” exploits in the Antarctic was received. There was no mention of whether the “Scheer” or any of the raiders would operate in that area.

At 2000 that day another signal was received requesting “Ship 33” to report whether “Weddelmeer” (codename for the Antarctic operational area) would prove to be a profitable hunting ground for the “Scheer”. “Ship 33” was ordered to proceed with the “Wegger” and the ten whalers to point “Andalusia”, where she was expected to arrive during the first ten days In February. The “Scheer” and the “Nordmark” were to provide the necessary prize crews to man the whale factory ship “Wegger” and the ten whalers. The “Scheer’s” personnel would then be replaced by the Alsterufer.”

This meant that the “Scheer”, still with three prize crews on board, would have none left until early March, when the meeting with the Alsterufer would take place.

Captain Krancke reasoned that it would be far better if the whaling fleet awaited the arrival of the supply ship. Another advantage was that the “Scheer” was operating independently of “Ship 33”, so that the “Scheer” could proceed south at the end of January and then set course for her new operational area in the southern parts of the Indian Ocean.

At 2117 the following message was transmitted: “If orders are carried out will have no prize crews for February. Suggest merchant cruiser and company wait for supply ship”. Another signal followed stating: “Prize ship “Sandefjord” on her way to meet supply ship.” (The International distinguishing signal letters “LDJF” were used instead of the name “Sandefjord.”)

At 2000 on the 19th the “Scheer” continued her progress, on course 090 degrees.

After ‘action stations’ had been sounded, the vessel was closed to within 1,100 yards. The ship was brightly illuminated. She looked old, was unarmed and apparently belonged to a neutral country (Portuguese?). Captain Krancke let the ship go because he thought it was not worth while stopping her. At 0800 course was altered to 225 degrees.

Two masts were sighted at 1429, bearing 195 degrees. The “Scheer” altered course to eastward in order to approach the ship on a parallel course, shadow her and attack her soon after nightfall. The vessel was steering a course of 320 degrees along the Capetown to Freetown route.

29

Another vessel was sighted at 1529 on a bearing of 285 degrees. By that time her funnel could already be seen. Her course was estimated to be approximately 140 degrees. The distance between the two ships was anywhere from 33,000 to 38,500 yards. The only method of attack which could be applied in this instance was to wait until both ships were passing each other.

‘Action stations’ was sounded at 1608. The easternmost ship (Ship 11) had turned onto a westerly course at 1600. It was established later that she had seen the “Scheer’s” smoke plum.

Course was altered to westward and speed increased to ‘full speed ahead’.

The following signal procedure was adopted as soon as the “Scheer” had closed to within 22,000 yards of Ship 11.

“What ship?”

“Where are you bound for?”

“Where do you come from?”

“What is the name of the master?”

“What is your cargo?” etc.….

This made the ship turn towards.

She no longer seemed suspicious, and all the questions were promptly replied to. She turned towards to enable the cruiser to make a quick ‘survey’.