H-054-1: Inchon Landing and Naval Action in the Korean War, September−October 1950

Senior U.S. commanders inspect the Inchon port area, 16 September 1950. This appears to be in the Red Beach area, with the northern end of Wolmi-Do island in the background. Those present in the front row are (from left to right): Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, USN, Commander, Joint Task Force Seven; General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief, Far East Command; and Major General Oliver P. Smith, USMC, Commanding General, First Marine Division. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-421944)

From the onset of the North Korean invasion of the Republic of Korea (ROK) on 25 June 1950, U.S. and South Korean forces slowed, but could not stop, the invading North Korea People’s Army. By late August 1950, North Korean forces had United Nations (mostly U.S. and ROK) troops pinned with their backs to the sea in an enclave around the port of Pusan (known as the Pusan Perimeter) in the southeastern corner of the Korean peninsula. Had the U.S. not had command of the sea, the U.N. forces almost certainly would have been pushed into the sea, or into POW camps. A steady stream of supplies and reinforcements, especially the 1st Provisional Brigade of the U.S. Marine Corps, all brought in by sea, enabled the Pusan Perimeter to hold, barely. Strikes from U.S. (and British) carrier aircraft on North Korean logistics lines as well as close-air support from Marine aircraft flying from U.S. Navy escort carriers were also a key factor preventing the North Koreans from overrunning the perimeter.

North Korean Offensive against Pusan Perimeter Resumes−31 August 1950

Despite high casualties and losses to their logistical support lines, on the night of 31 August/1 September the North Korean Army launched their biggest offensive yet to break through U.S. Army and ROK Army positions around Pusan (and they did in spots, which were plugged by counterattacking U.S. Marines). Nevertheless, the North Korean attacks were initially relentless, and the situation was quickly deemed “critical” by senior U.S. commanders.

As it became apparent by the morning of 1 September that a massive North Korean attack was underway, the two U.S. carriers engaged in the Korean combat area, Valley Forge (CV-45) and Philippine Sea (CV-47) were almost 300 mile to the northwest in the Yellow Sea conducting airstrikes on targets near the North Korean capital of Pyongyang and southward to the (former) capital of South Korea, Seoul. The 0800 launch from Valley Forge dropped the span on a key railroad bridge, while the strike from Philippine Sea hit and damaged the Pyongyang railroad bridge and marshaling yards. Jet fighter sweeps from both carriers hit targets along the coast from Seoul to the North Korean port of Chinnampo.

The first Task Force-77 (TF-77) morning air strikes had just returned, and the carriers were gearing up for another round of strikes, this time by AD Skyraiders, when urgent requests to assist with the crumbling defense of the Pusan Perimeter came in. The commander of the carrier task force (TF-77), Rear Admiral Edward C. Ewen, immediately directed TF-77 to steam southeast at 27 knots. (RADM Ewen had been awarded a Navy Cross in command of light carrier Independence during World War II. He assumed command of TF-77 on 31 July 1950). Strikes that were airborne north of Seoul were ordered recalled and combat air patrol (CAP) fighters were vectored to guide the strike aircraft back to the carriers’ moving position.

At 1233 1 September, CTF-77 reported that the first strikes in support of the Pusan Perimeter would launch at 1315 and be on station by 1430. The first strike package of twelve AD Skyraiders, with three 1,000-pound bombs each, and 16 F-4U Corsairs with one 1,000-pound bomb and four rockets each, reached the Pusan area by 1430. The USN strikes quickly encountered the control problems that had plagued earlier close-air support efforts in Korea. Fourteen USN aircraft were directed to bomb a concentration of tanks; fortunately, the strike leader got suspicious that the tanks were making no effort to defend themselves and then he saw the white stars and aborted the strike. In another instance, a forward air-controller kept USN aircraft in orbit and vectored in a F-51 Mustang instead, even though the USN aircraft had ordnance better suited to the task. Of 83 USN sorties in support of the Pusan Perimeter that day, only 43 were under positive control and the rest had to search on their own for something useful to blow up.

Unfortunately, the North Korean offensive caught both escort carriers (Sicily (CVE-118) and Badoeng Strait (CVE-116)), with their two embarked Marine Corsair squadrons (VMF-214 and VMF-323) away from the area, at Sasebo for replenishment and upkeep. Badoeng Strait’s Marine aircraft were already temporarily ashore at Ashiya Airfield, Japan, and Sicily was ordered to put her Marine squadron ashore as well. Severe weather caused by the approach of Typhoon Jane initially hampered the Marine aircraft, with their close-air support expertise, from getting in the fight on the first day.

On 2 September, desperate fighting continued along the perimeter although the North Korean advance started to grind to a halt. U.S. Navy air controllers went ashore to work with the U.S. Army Second Infantry Division to iron out the control problems. The Marine squadrons from Ashiya also got into the fight despite the long distance and bad weather. The TF-77 carriers contributed 127 strike sorties, while the Fifth Air Force in Japan and the Marine aircraft from Ashiya combined for another 201 sorties; this time 99 of the USN aircraft bombed under positive control; morning fog was the primary reason for those that didn’t receive positive control targets. The afternoon attacks by Valley Forge and Philippine Sea. By 3 September, the U.S. Army and ROK lines had mostly stiffened and the Marines were pushing the North Koreans back in the Second Battle of Naktong River Bulge, and by 4 September, Marine aircraft from Japan were hitting retreating North Korean forces in the Naktong sector.

Yellow Sea Mine Sighting and USN Shootdown of Soviet Torpedo-Bomber – 4 September 1950

With the situation around Pusan somewhat stabilized, TF-77 moved back north in the Yellow Sea to resume strikes into North Korea, although deteriorating weather cut this short. On 4 September, destroyer USS McKean (DD-784) sighted and destroyed four floating mines in the Yellow Sea southwest of the North Korean port of Chinnampo. Three days later British ships in the same area reported many floating mines. These were some of the first indications of what would prove to be a major problem as the Soviets were supplying thousands of sea mines to the North Koreans.

At 1329 on 4 September, destroyer Herbert J. Thomas (DD-833) had assumed radar picket duty 60 NM north of the TF-77 carriers in the Yellow Sea when she made contact on unidentified aircraft closing from the direction of the Soviet air base at Port Arthur (in Manchuria, China) on course 169 degrees, speed 180 knots, and altitude of 12-13 thousand feet. Carrier Valley Forge gained radar contact shortly afterward and destroyer USS Fletcher (DD-445) was directed to vector a division of four Valley Forge F-4U Corsairs to intercept.

As the fighters closed, the contact split as one aircraft turned away, but the other aircraft increased speed and descended, continuing toward the carriers. The fighters intercepted the contact at 30 NM from the carrier and identified it as a twin-engine medium bomber. As the division leader, Lieutenant (junior grade) Richard E. Downs, closed in from overhead near enough to see the red stars on the wings, the dorsal gunner on the bomber opened fire. Downs attempted to maneuver to attack but couldn’t get in position to shoot before his wingman, Ensign Edward V. Lancey, hit the plane with machinegun fire. As the other section of Corsairs was closing in, the plane’s wing came off and it went into a flaming flat spin into the sea. Herbert J. Thomas saw the smoke from the plane crash and fished one Russian aircrewman out of the sea who could not be resuscitated, despite extensive effort to do so.

The Soviet aircraft was an A-20 Havoc (NATO code name “Box”) torpedo bomber subordinate to the 36th Mine-Torpedo Regiment of the Soviet Red Banner Pacific Fleet. The U.S. had supplied over 3,400 of the U.S.-designed and built A-20 aircraft to the Russians during World War II, about 700 of which were subordinated to the Soviet Navy. The aircraft were flown from the U.S. to Russia via the Alaska-Siberia ferry route. The U.S. returned the body of the airman to the Soviets in 1956.

On 5 September, bad weather precluded TF 77 strikes into North Korea. In addition, the North Koreans achieved some success at the eastern end of the Pusan Perimeter, breaking through ROK forces and threatening to take the port of Pohang (north of the much larger port at Pusan). This prompted more calls for urgent air support. The escort carrier Sicily was still in upkeep in Sasebo. Badoeng Strait was underway, but typhoon conditions prevented her from launching aircraft. Once again, TF 77 sprinted back to the southeast to assist. The North Korean drive toward Pohang was initially blunted by gunfire from heavy cruiser Toledo (CA-133) and destroyer De Haven (DD-727) which broke up a tank attack and destroyed artillery. De Haven also vectored 5th Air Force aircraft in to successful attacks on North Korean armor and troop concentrations. Still, the North Koreans broke into Pohang early on 6 September, but failed to gain control of the airfield. That would prove to be the high-water mark of the last North Korean offensive. By then the cumulative toll of heavy casualties in the attacks and severe disruption of their logistics lines left the North Koreans unable to continue the attack. Rivers swollen by Typhoon Jane rains also cut off some of their forward units from rear elements on the west side of rivers.

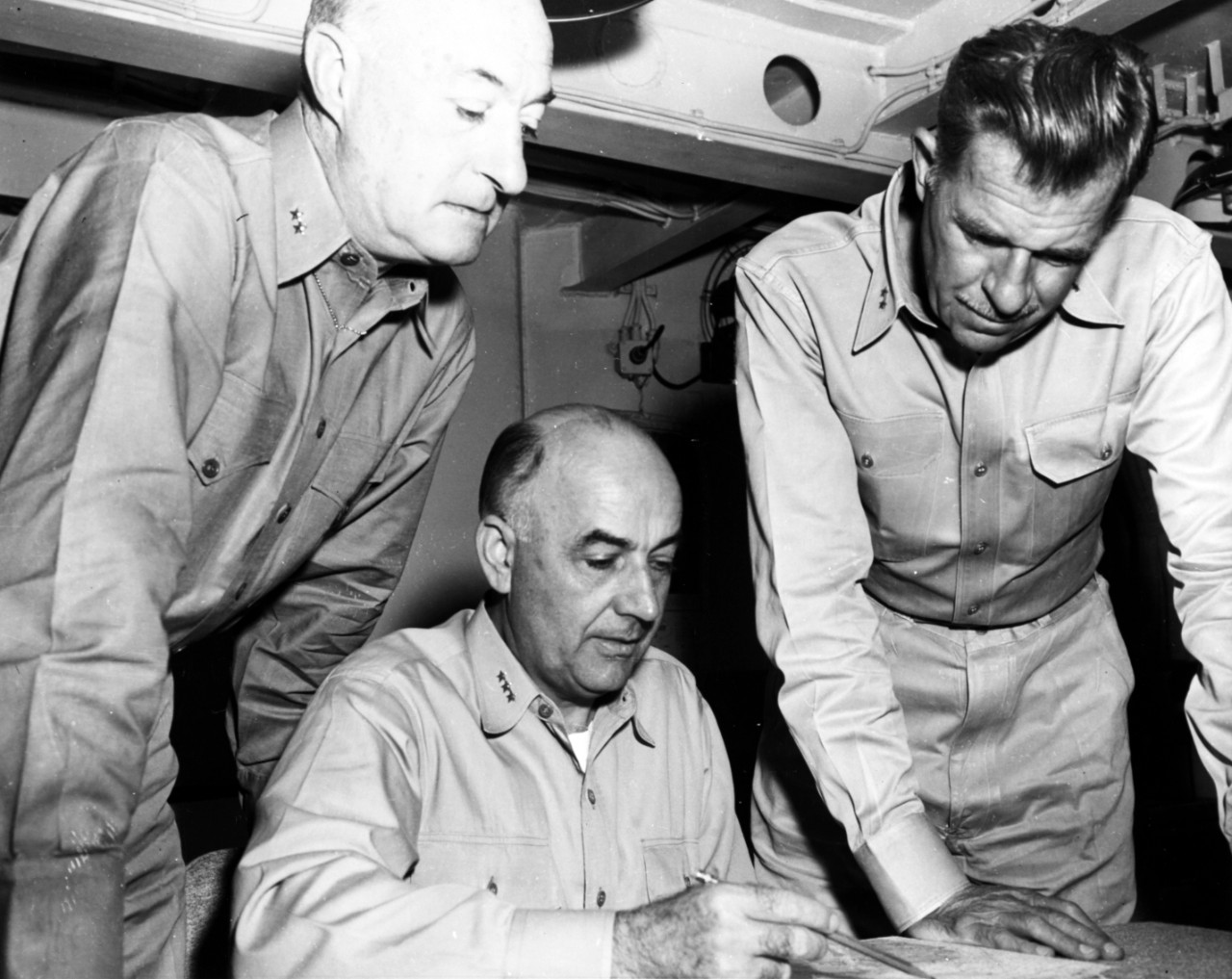

Flag conference on board USS Rochester (CA-124), flagship of Joint Task Force Seven, during the Inchon operation. Those present are (from left to right): Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, USN, Commander, Task Force 90; Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, USN, Commander, Joint Task Force Seven; and Rear Admiral John M. Higgins, USN, Commander, Task Group 90.6. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-668791)

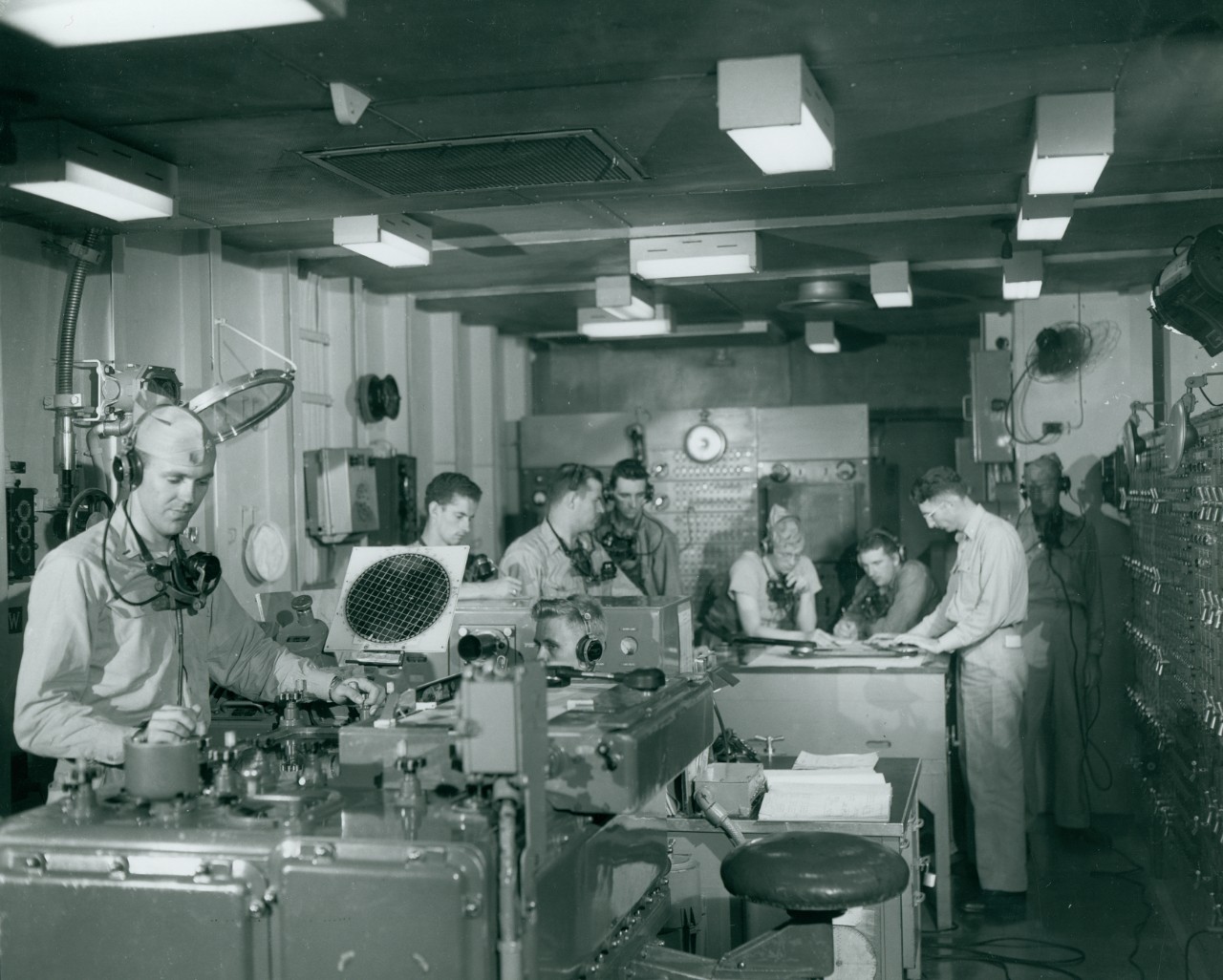

Joint Task Force Seven (JTF 7) was formed effective as of midnight 10-11 September with the mission to land X Corps (TF-92) at Inchon. JTF 7 was under the command of Seventh Fleet Commander, VADM Struble, who embarked on heavy cruiser Rochester (CA-124). X Corps was commanded by Major General Edward Almond, U.S. Army, and consisted of the 1st Marine Division (Major General Oliver Smith, USMC) and the U.S. Army 7th Infantry Division (of which 8,000 were hastily trained Korean troops, known at “Katusa.”) The Marines would conduct the initial amphibious assault on Inchon and the Army troops would be disembarked afterward. VADM Struble was in charge of the operation until all the ground troops were ashore and then command would be transferred to Major General Almond.

The Commander of the Attack Force (Task Force 90) was Rear Admiral James Doyle, embarked on amphibious command and control ship Mount McKinley (AGC-7), along with General MacArthur and Major General Almond (Lieutenant General Shepherd also stayed aboard for the show). TF 90 included two escort carriers (Sicily and Badoeng Strait), two heavy cruisers (Rochester and Toledo), three light cruisers (Manchester (CL-83), HMS Jamaica, and HMS Kenya), 12 destroyers, one destroyer escort, four ROKN patrol boats (PC), eight patrol frigates (three USN, two Royal Navy, two Royal New Zealand Navy, and one French Navy), and one Patrol Escort, Control (PCEC). The minesweeper force included one minesweeper (AM), six motor minesweepers (AMS), and seven ROKN auxiliary motor minesweepers (YMS). Major amphibious ships included two amphibious command and control ships (AGC); three fast-transports (APD); five landing ship, dock (LSD); and three rocket ships (LSMR). The force had 47 landing ship, tank (LST) of which 30 were manned by Japanese crews. There was one hospital ship, Consolation (AH-15). Transports included 30 Military Sea Transport Service (MSTS) vessels, 20 U.S. commercial cargo ships on time charter, and four Japanese cargo ships. The force totaled about 120 ships to lift troops and about 230 ships overall.

Task Force 91, the Blockade and Covering Force, was commanded by Rear Admiral Sir William. G. Andrewes, RN, and included the carrier HMS Triumph, one light cruiser, and eight destroyers.

Task Force 77, the Fast Carrier Force, was commanded by RADM Edward C. Ewen, and included carriers Valley Forge, Philippine Sea and Boxer (CV-21), one light cruiser, and 14 destroyers.

Task Force 99, the Patrol and Reconnaissance Force, was commanded by RADM George R. Henderson and included two seaplane tenders (AV), one small seaplane tender (AVP), with three U.S. Navy and two Royal Navy patrol squadrons.

Task Force 79, the Service Squadron, was commanded by Captain B. L. Austin and included 21 various auxiliaries including destroyer tenders, oilers, and an ammunition ship, tugs, and salvage vessels.

The supporting Task Forces totaled about 52 ships.

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (seated, center), Commander-in-Chief, Far East Command, on board USS Mount McKinley (AGC-7) during the Inchon landings, 15 September 1950. The others present are (from left to right): Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, U.S. Navy, Commander, Task Force 90; Brigadier General Edwin K. Wright, U.S. Army, MacArthur's Operations Officer; and Major General Edward M. Almond, U.S. Army, Commander, Tenth Corps. Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives. (SC 348448)

Preliminary Naval Operations prior to Inchon – Early September 1950

Although the U.S. Navy commander of the ROK Navy, Commander Michael Luosey (CTG 96.2) was not read into the planning for Operation Chromite, he directed a series of offensive ROKN operations along the west coast of Korea in the weeks leading up to the Inchon landing. On 15 August 1950, CDR Luosey sent a plan to COMNAVFE that “unless otherwise directed” the ROKN planned to capture several islands near the entrance to the channel to Inchon. With no negative response received, “Operation Lee” commenced with ROKN patrol boat PC-702 and two auxiliary motor minesweepers (YMS) with support from Canadian destroyer HMCS Athabaskan. The ROKN ships put a 110-man landing party ashore on Tokchok Do, and then on 19 August, put the force ashore on Yonghung Do, while Athabaskan put a landing party onto Palmi Do and destroyed radio gear at the lighthouse. The landing at Yonghung Do had the unplanned effect of causing the North Korean defenders of Inchon to think a landing might take place south of Inchon and began shifting forces in that direction.

On 1 September, Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark, USN, arrived in the Tokchok Islands aboard destroyer HMS Charity and in conjunction with ROKN personnel already there quickly set up a highly effective intelligence gathering network that obtained extensive intelligence on Inchon defenses and hydrographic features, while also conducting raids and engaging in several sampan-to-sampan gun battles with North Korean forces. Lieutenant Clark carried a grenade with him to kill himself in the event of imminent capture. He was awarded a Silver Star for his actions from 1-15 September, which included a personal reconnaissance of Wolmi-Do (not specifically mentioned in the award citation) and a Navy Cross for actions on 13-14 September, including turning on the navigation beacon on Palmi Do to assist U.S. destroyers and cruisers though the narrow channel to Inchon.

Lieutenant Clark’s Navy Cross citation: “The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant Eugene Franklin Clark, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving with Special Operations Group, G-2, Headquarters, Far East Command, in enemy held territory in North Korea (ed., actually North-Korean occupied South Korea) on 13 and 14 September 1950. Lieutenant Clark was a member of a special operations group which landed in enemy-occupied territory to perform a confidential mission. Lieutenant Clark, in charge of the shore party, proceeded by boat from an offshore rendezvous lying approximately twenty miles offshore through rough seas to a point approximately 200 yards off the beach of enemy-held territory, known to be occupied and in the process of being mined by Chinese Communist Forces (ed., actually North Korean and South Korean Communist sympathizers) in anticipation of an invasion by United States Forces. He then transferred to a small rubber boat and landed through the surf on a beach where he contacted friendly personnel who had been operating in that area. He then proceeded inland to the vicinity of an enemy-occupied village, reconnoitered the area and posted guards at the village and northward from the landing point to intercept Chinese Communist (sic) patrols in order to protect the remainder of the party during the performance of the confidential mission. On completion of the mission he returned by rubber boat through surf that had subsequently become heavier and increasingly dangerous to the offshore rendezvous. The hazards of capture based on losses of preceding groups, together with warnings received from ashore that the enemy was aware of the planned operation did not deter this gallant officer from continuing to volunteer and successfully completing the mission. He was well aware that if he fell into the hands of the enemy, who were on the alert and occupying the entire area, he could anticipate the same fate as those who had preceded him; that is, torture followed by death. Lieutenant Clark’s display of outstanding courage and gallantry uphold the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

The plan for the Inchon landing required the incorporation of the 5th Marine Regiment (the core of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade), which had been so valuable in the Eighth Army’s defense of Pusan. The commander of the Eighth Army, Lieutenant General Walker, resisted letting the Marine Brigade go while there was still risk of further North Korean attacks. X Corps Commander, Major General Almond proposed using a regiment of the 7th Infantry Division in place of the Marine brigade. VADM Struble rejected the idea as he did not want a force with no training in amphibious operations to be in the initial assault. Struble’s argument prevailed, although the Navy had to transport another Army regiment from Japan to Pusan to backfill the Marines.

On 5 September 1950, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade began disengaging from contact with the enemy on the Pusan Perimeter and on 8 September began embarking ships at Pusan. Between 8-12 September, the 7th Marine regiment began arriving in Japan from the U.S. to transfer to assault shipping, which was disrupted and delayed by the approach of Typhoon Kezia. By 10 September, the slower elements of TF 90 were underway, ordered out a day early by VADM Struble to try to beat Typhoon Kezia to the Tsushima Strait as the typhoon and the bulk of TF 90 were originally scheduled/forecast to be in the strait at same time. Fortunately, the Typhoon re-curved to the northeast, but the very heavy seas still made for a miserable transit for embarked troops.

In preparation for Operation Chromite, the fast carriers of TF77 had temporarily withdrawn from the Yellow Sea for upkeep at Sasebo. Nevertheless, air strikes continued on the west coast from HMS Triumph and Badoeng Strait. A UN surface force under RADM Andrewes, RN, bombarded Inchon on 5 September and then shelled Kunsan on 6 September, while Triumph raced around to the Sea of Japan to attack Wonsan on the east coast of North Korea as part of a deception effort. The escort carrier Sicily arrived in the Yellow Sea as Triumph left. The Marine aircraft on the escort carriers continued to hit targets up and down the west coast of South Korea to keep the North Koreans from figuring out exactly where the landing would occur. As part of the diversion effort, the heavy cruiser Helena (CA-75) delivered some very accurate shooting and dropped key bridge span at Kanggu Hang, north of Pohang, on the east coast of South Korea. In an operation that should have been a dead giveaway that Inchon was the target, but that was considered a necessary risk, the Marine aircraft on the escort carriers were ordered to burn the western half of Wolmi Do, the island in the inner Inchon harbor. The Marine aircraft used 95,000 pounds of napalm to do it.

On 10 September 1950, as Operation Lee continued along the west coast of South Korea, the ROKN patrol boat PC-703 sank a minelaying sailboat off Haeju, another indication that the North Koreans were engaging in widespread minelaying activity. Fortunately, the North Koreans were concentrating minelaying at Kunsan and Mokpo, which the North Koreans assessed as more likely landing areas. The North Koreans would belatedly start to mine Inchon, but it would be a case of too little too late. This is where MacArthur’s intransigent emphasis on speed paid off; had the operation been delayed a month, Inchon would have been heavily mined, with severe consequences, as the small TF 90 minelaying force was inadequate to the task.

On 12 September, ROKN PC-703 sank three more North Korean watercraft in the approaches to Inchon. The same day, TF 77 returned to the Yellow Sea to attack targets on the west coast and to attempt to seal off approaches to Inchon to thwart any North Korean attempt at reinforcement. In the meantime, HMS Triumph returned to the Yellow Sea and her aircraft concentrated on Kunsan as part of the continuing deception effort.

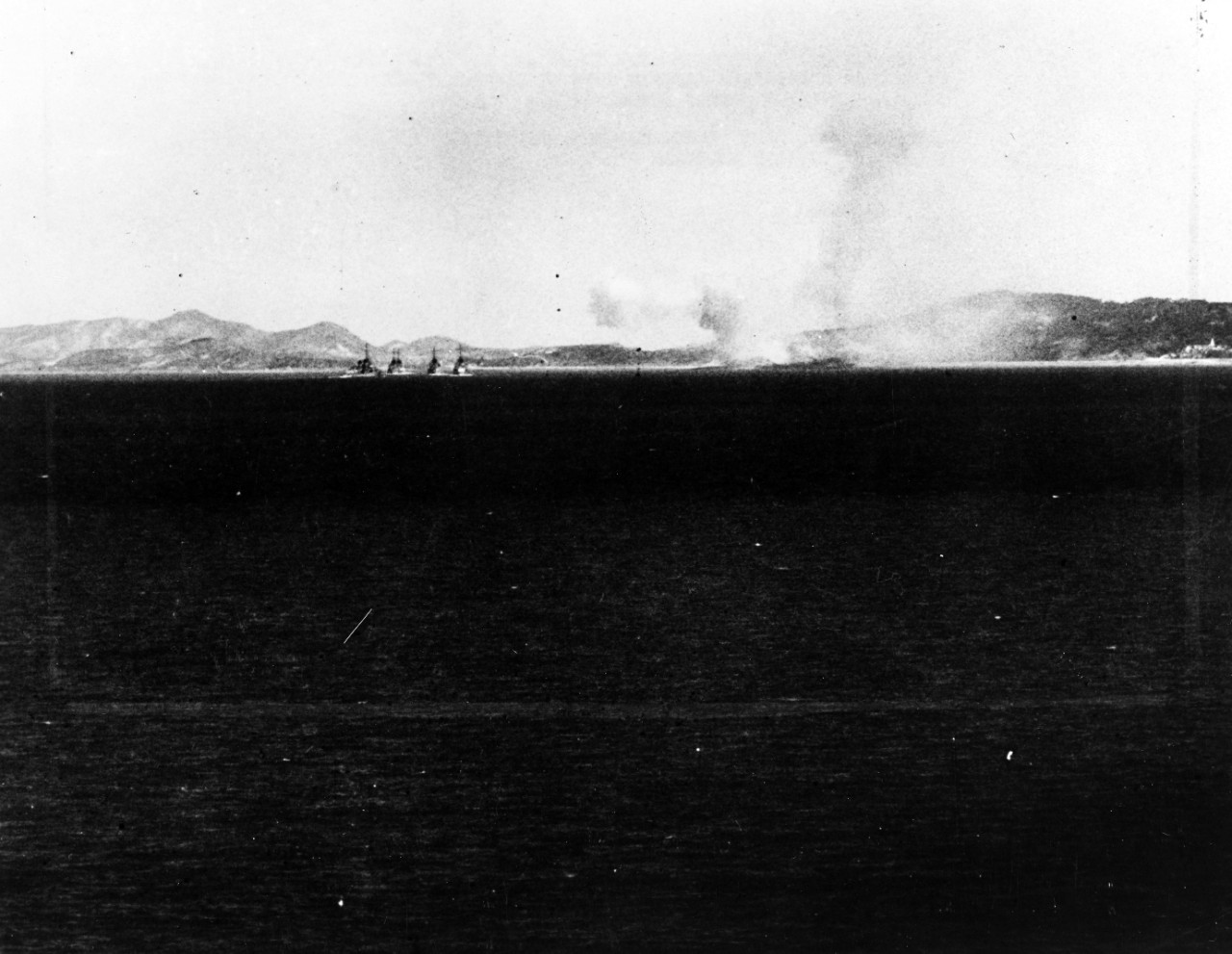

Wolmi-Do island under bombardment on 13 September 1950, two days before the landings at Inchon. Photographed from USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729), one of whose 40mm gun mounts is in the foreground. Sowolmi-Do island, connected to Wolmi-Do by a causeway, is at the right, with Inchon beyond. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-420044)

Wolmi Do: The Battle of the “Sitting Ducks” − 13-14 September 1950

The critical initial objective of the Inchon landing was the small island of Wolmi Do in the inner harbor. The island was triangular in shape and about half a mile per side, and connected to the city of Inchon by a 900-yard causeway. It was believed to be heavily fortified (and it did have a garrison of about 400 troops). From the island, North Korean artillery could hit the landing craft from the flanks at near pointblank range as they headed to Red Beach to the north of Wolmi Do and Blue Beach to the south. The LSTs would have been extremely vulnerable to fire from Wolmi Do. The plan called for two days of shelling and airstrikes on Wolmi Do and to capture it in advance of the main landing, even at the cost of surprise. The hydrography would make this one of the most difficult bombardment operations in U.S. Navy history.

First and second waves of landing craft move toward Red Beach at Inchon at 0700. USS De Haven (DD-727) is in the foreground. Photographed from a Marine Air Group Twelve (MAG-12) aircraft from either VMF-214 or VMF-215. This view looks eastward. The Inchon industrial area is in the middle distance, with fires burning and smoke drifting south over the city. Courtesy of Colonel Robert D. Heinl, USMC, June 1966. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. (NH 42351)

On 13 September, in broad daylight, because there was no choice, the bombardment force would have to come up the narrow channel single file with the flood tide and anchor less than half a mile off Wolmi Do with head toward the sea, and would have about two hours to shell the island before getting stranded in the mud by the ebb tide. At 0700, the commander of Destroyer Division Nine One/Destroyer Squadron Nine (DESDIV 91/DESRON 9TE 90.62), Captain Halle C. Allen, Jr. embarked on destroyer Mansfield, led the column of ships into the narrow channel. Following Mansfield were the destroyers De Haven (DD-727), Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729), Collett (DD-730), Gurke (DD-783), and Henderson (DD-785). Following the destroyers were the heavy cruiser Rochester (with Commander JTF-7, VADM Struble embarked), heavy cruiser Toledo (CA-133) (with Commander Gunfire Support Group (TG 90.6), RADM John M. Higgins embarked), and British light cruisers HMS Jamaica and HMS Kenya. The cruisers could only go as far as the outer harbor.

Five U.S. Navy destroyers steam up the Inchon channel to bombard Wolmi-Do island on 13 September 1950, two days prior to the Inchon landings. Wolmi-Do is in the right center background, with smoke rising from air strikes. The ships are USS Mansfield (DD-728); USS DeHaven (DD-727); USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729); USS Collett (DD-730) and USS Gurke (DD-783). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-419905)

At 1145, a string of 17 moored contact mines was sighted in the location where British ships had shelled Inchon on 5 September. As the bombardment force had no minesweeping capability, this forced a critical decision. The tide and the schedule left no time for delay, and VADM Struble made the decision to press ahead despite the risk of more mines. The lead destroyers opened fire on the mines and Lyman K. Swenson destroyed one mine with 40mm fire. The trail destroyer, Henderson, was detached from the column to attempt to destroy the rest of the mines with gunfire. As the destroyers anchored in position off Wolmi Do, TF 77 aircraft orbiting overhead then bombed the island.

At 1300, the destroyers opened fire on Wolmi Do from a range of just under a half mile. After several minutes, North Korean shore batteries began to return fire, concentrating on Lyman K. Swenson, Collett and Gurke. Collett was hit nine times by 75mm shells, which disable her fire control computer, but she kept firing in local control. Gurke was hit three times. Despite the return fire and the “sitting duck” nature of the bombardment (which the press played up), the destroyers poured over 1,000 rounds of 5-inch shells into the island in one hour. As the destroyers retired down the channel, several North Korea guns were still defiantly shooting. Fragments from a near miss killed Lieutenant (junior grade) David H. Swenson. Once the destroyers cleared, the cruisers opened up from position in the lower (outer) harbor, blasting Wolmi Do with 8-inch and 6-inch gunfire until about 1640.

A chaplain reads the Last Rites service as Lieutenant (Junior Grade) David H. Swenson is buried at sea from USS Toledo (CA-133), off Inchon, Korea. He had been killed by North Korean artillery while his ship, USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) was bombarding enemy positions on Wolmi-do island, Inchon, on 13 September 1950. Lyman K. Swenson is in the background, with her crew at quarters on deck. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the All Hands collection at the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 96980)

During the bombardment, U.S. Intelligence intercepted a message from the commander of North Korean defenders at Inchon reporting the shelling with a warning that “every indication enemy will perform a landing.” However, with some of the defenders out of position, having been faked out by the ROKN landing on Yonghung Do, and the roads to Inchon interdicted by TF 77 and Marine aircraft, it was too late.

RADM Higgins and Captain Allen conferred with VADM Struble on Rochester that night. Given the vigorous North Korean defense and the fact some guns were still firing as the destroyers left, VADM Struble ordered the operation repeated on 14 September. Collett was temporarily detached to deal with her damage. The tug Mataco (ATF-86) was assigned to deal with the remnants on the minefield.

Commencing at 1050 on 14 September, more airstrikes pounded Wolmi Do. At 1110, the cruisers opened up from positions in the lower harbor, covering the second approach of the destroyers to Wolmi Do. Shortly after noon, the destroyers arrived in position. This time enemy fire was sparse and inaccurate. More aircraft bombed the island. Between 1255 and 1422, the destroyers poured 1,700 5-inch rounds at pointblank range into the island, with improved air spotting over the first day. RADM Higgins and Captain Allen were each awarded the Silver Star for the two-day action, as was Commander Robert H. Close, Commanding Officer of Collett, and CDR Edwin Headland, Commanding Officer of Mansfield. (Probably each of the skippers of the “sitting duck” destroyers were awarded a Silver Star).

LCVPs from USS Union (AKA-106) circle in the transport area off Inchon, prior to going to the line of departure on the first day of landings, 15 September 1950. An LST, wearing the side number QO-12, is in the center background. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-423215)

D-Day, Inchon − 15 September 1950

There were two approaches to Inchon. Due to the reconnaissance by Lieutenant Clark and his South Korean team (which among other things verified that the WWII Japanese tide tables for Inchon were correct and U.S. tide tables were not) the Su Sudo (Flying Fish) Channel was selected. Although the tidal currents were quite fast, there were fewer obstructions.

Shortly after midnight, the Gunfire Support Group entered, followed by the Advance Attack Group (led by Captain Norman W. Sears, USN), with the 3rd Battalion/5th Marine Regiment embarked, who would take Wolmi Do in advance of the main landings later in the day. Following the destroyers was the Landing Ship Dock Fort Marion (LSD-22) with Captain Sears embarked, along with three Landing Ship Utility (LSU) on board loaded with ten tanks. Fast transports Horace A. Bass (APD-124), Diachenko (APD-123), and Wantuk (APD-125) carried the Marines. The cruiser force followed. Then came command ship Mount Mckinley, with General MacArthur, Marine LTG Shepherd, RADM Doyle, and Army Major General Almond embarked. Lieutenant Clark and his team lit the beacon on Palmi Do to aid the nighttime transit of the difficult channel. (Captain Sears would be awarded a second Silver Star; his first was as a lieutenant commander aboard light cruiser Atlanta (CL-51) sunk in the 13 November 1942 battle off Guadalcanal).

TF 77 carrier aircraft from Valley Forge and Philippine Sea launched before dawn to provide combat air patrol, barrier patrols, and deep support strikes, which would continue all day. The two escort carriers of Carrier Division 15 (RADM Richard W. Ruble), Sicily and Badoeng Strait, launched ten Marine Corsair fighter-bombers for a pre-landing attack on Wolmi Do, and provided gunfire spotting, CAP, and deep support all day as well.

By 0528 15 September, all ships were in position. The Advanced Attack Group used Wolmi Do as cover from any fire from the Inchon waterfront. At 0540, Captain Sears gave the order to “Land the Landing Force.” At 0545 the destroyers opened fire. Mansfield, De Haven, and Lyman K. Swenson concentrated on Wolmi Do and the northern shore of Inchon around Red Beach. Collett (back in action), Gurke, and Henderson concentrated on the shoreline of Inchon to the south of Wolmi Do toward Blue Beach. From the southern fire support area, cruisers Toledo and HMS Kenya blasted targets from Blue Beach and northwards, while Rochester and HMS Jamaica hit targets to the south of Blue Beach. By 0600 the Marines of the Wolmi Do assault force were loaded on the landing craft, ready to head for Green Beach on Wolmi Do. At 0615 the three LSMR “Rocket Ships” unleashed a barrage of 1,000 5-inch rockets each. The rocket barrage and ship bombardment ceased for a final strafing of the Green Beach before the Marines landed on schedule at “L-hour,” 0630.

By 0633, the first Marines ashore on Wolmi Do with negligible resistance. At 0626, the three LSUs from Fort Marion hit the beach and landed the ten tanks. Within 30 minutes after the initial landing, the Marines had control of the northern end of the island. VADM Struble was getting into a small boat to make a close-in visual reconnaissance when Rochester received a visual signal from Mount Mckinley. “The Navy and Marines have never shone more brightly than this morning. MacArthur.” (And the main event hadn’t even started yet). VADM Struble stopped long enough to have MacArthur’s message relayed to fleet, before re-embarking the boat, which then proceeded to Mount Mckinley to pick up General MacArthur for a reconnaissance of the inner harbor (joy ride?) and survey of Wolmi Do. By noon, all opposition on Wolmi Do ceased. The island was found to have been fortified with numerous trenches and defensive positions, which had proved no match for napalm, airstrikes, and cruiser-destroyer bombardment. The Marines suffered 14 wounded in the capture of Wolmi Do.

Inchon Main Landings – Afternoon 15 September 1950

Because of the tides, the next phase of the operation, the assault on Inchon itself, could not occur until later in the afternoon. However, air strikes and some naval gunfire continued throughout the day, with considerable care taken to avoid collateral damage to civilian areas of Inchon. After 1300, the LSTs and transports began coming up the channel with the tide.

First wave of U.S. Marines heads for the landing beach in LCVPs, 15 September 1950. This landing is probably that on Red Beach, on the northern side of the Inchon invasion area. PC at the far right is a unit of the Republic of Korea Navy. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 96877)

TF 77 was reinforced that afternoon by the just-in-time arrival of the carrier Boxer (CV-21), with an all-propeller Air Group, four squadrons of F4U Corsairs, and one squadron AD Skyraiders. Boxer had made record-breaking transits to and from Japan in late July/early August as an aircraft ferry for mostly U.S. Air Force aircraft. After a quick turnaround (which deferred yet again critical maintenance) she embarked Air Group Two and made another high-speed transit of the Pacific, dodging Typhoon Kezia and plowing through heavy seas, which delayed her arrival. Almost immediately she suffered a reduction gear failure that took one of her four shafts offline, limiting her speed to 26 knots for the duration of her deployment. Nevertheless, her aircraft immediately contributed to close-air support and interdiction missions in and around Inchon. Arriving with Boxer was the light cruiser Manchester and two destroyers.

At 1615 15 September 1950, strike groups from TF 77 began bombing and strafing Red Beach at the north end of Inchon and Blue Beach toward the south end. By 1700, the tides allowed the destroyers back in position and shore bombardment commenced in earnest. Rain squalls and heavy smoke diminished visibility as 500 landing craft headed for the beaches. Armored LVT amphibious assault vehicles carrying Marine Regimental Combat Team ONE (RCT 1), led by Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller (picking up a Silver Star to go with his five Navy Crosses), made for Blue Beach while the faster LCVP landing craft carrying RCT 5 aimed for Red Beach. DUKW amphibious vehicles carried 105mm artillery to be set up on Wolmi Do.

With twenty-five minutes before H-hour, the three LSMR Rocket Ships commenced fire. This time LSMR-402 fired 2,000 rockets at Red Beach, while the other two hit Blue Beach and the tidal basin between Blue Beach and the causeway to Wolmi Do. The strong tidal currents pushed the two southern LSMRs out of position, and for a time the rockets were passing directly over Marine-laden landing craft, reportedly a most disconcerting experience. At 1725 the rocket fire ceased and another airstrike hit the beaches. The Marines hit the beach on schedule at 1730.

At Red Beach, the Second Battalion of the 5th Marines (RCT 5) landed first and encountered only scattered rifle, automatic weapons, and mortar fires. The North Korean resistance caused some delay, although the nature of the beach caused more, as Marines had to scale ladders up the seawall while other piled up behind them on the narrow (at high tide) mud flats. Marine First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez was hit by automatic weapons fire while in the act of throwing a grenade; although severely wounded he crawled onto the grenade to save his men; he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Nevertheless, within an hour the Marines were well into town, moving toward key terrain with the “situation well in hand.” Tanks and Marines crossing the causeway from Wolmi Do into Inchon met little resistance. (First Lieutenant Lopez was captured in one of the iconic photographs of the battle leading his platoon over the seawall under fire. The photograph was taken by Marguerite Higgins, a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, who had witnessed the liberation of Dachau death camp in WWII and would be the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence, for her coverage of the Korean War).

First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez, USMC, leads the 3rd Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines over the seawall on the northern side of Red Beach, as the second assault wave lands, 15 September 1950. Wooden scaling ladders are in use to facilitate disembarkation from the LCVP that brought these men to the shore. Lt. Lopez was killed in action within a few minutes, while assaulting a North Korean bunker. Note M-1 Carbine carried by Lt. Lopez, M-1 Rifles of other Marines and details of the Marines' field gear. U.S. Marine Corps Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 96876)

Resistance at Blue Beach was more intense and mortar fire rained down on the LVTs as they came ashore. One LVT was destroyed by a direct mortar hit before gunfire from destroyer Gurke silenced the mortar positions. Difficulty getting off the beach caused the wave to turn into a column, which was also hampered by smoke and rain. Nevertheless the Marines advanced inland without too much difficulty as night fell. Although there was some fighting in the city during darkness, by midnight the Marines had taken their planned objectives. The destroyers and cruisers remained on call, with Toledo assigned to the Marine Division Headquarters, Rochester to the 5th Marines, Jamaica to the 1st Marines, and a destroyer designated to support each battalion. Illumination rounds from the ships were not effective on the first night as the destroyers were too close and the cruisers too far for the starshells to be employed properly, but on following nights illumination rounds from the ships proved very valuable.

Marine casualties on the first day of the operation totaled 174, including 20 killed in action, one missing in action, and one died of wounds. The North Korean 226th Marine Regiment was assigned to defend Inchon with an estimated 1-2,000 personnel. A comparatively new and ineffective force, it proved no match for the U.S. Marines. The force had been weakened when a sizable number reacted to the earlier ROKN landing on Yonghung Do. As the U.S. Marines were storming ashore at Inchon, North Korean Marines had just stormed ashore from junks at Yonghung Do to find that Lieutenant Clark, the ROKN boats, and ROK guerrillas had evacuated the island just ahead of them. The North Koreans then massacred about 50 civilians who had chosen to remain behind.

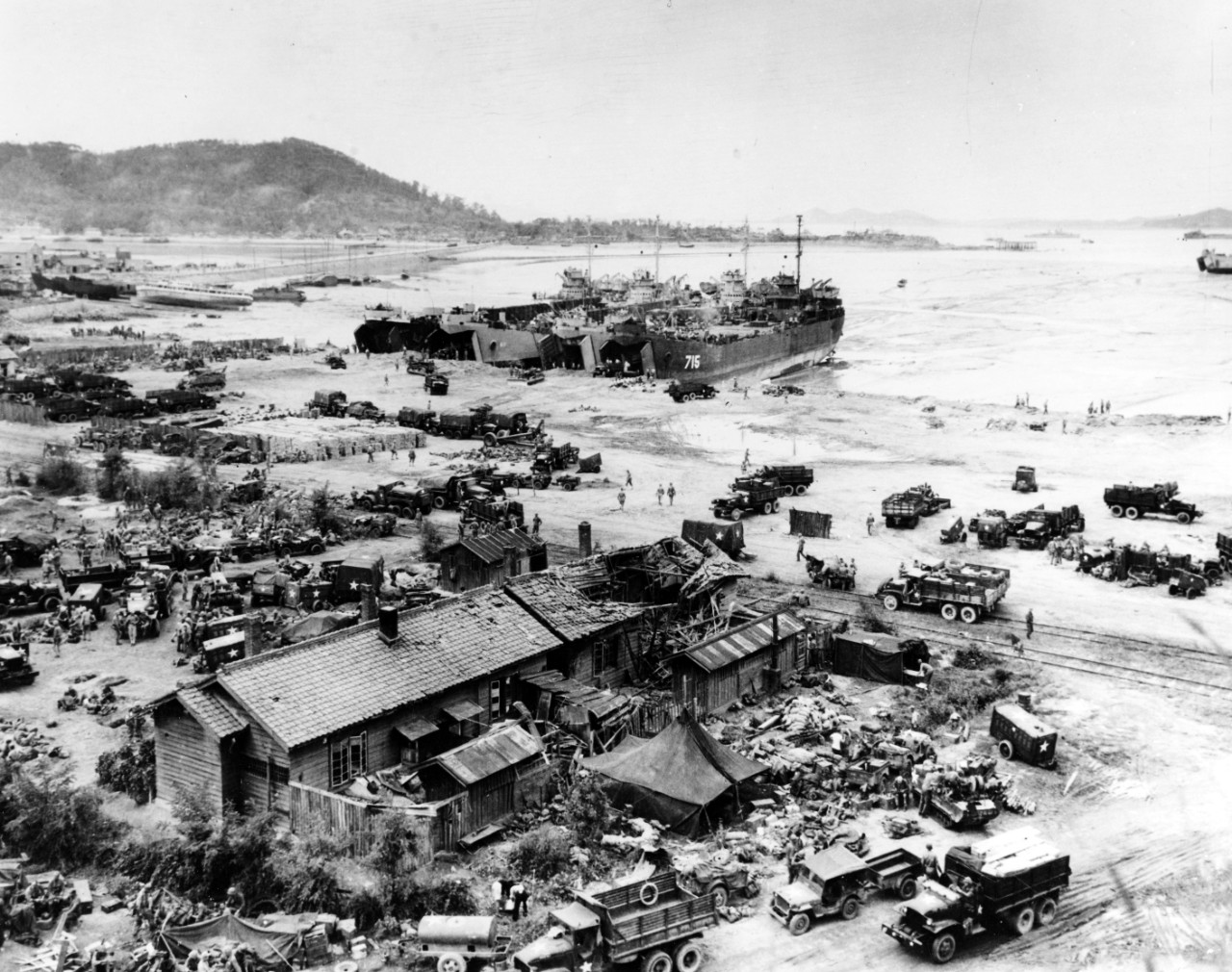

Four LSTs unload men and equipment while high and dry at low tide on Inchon's Red Beach, 16 September 1950, the day after the initial landings there. USS LST-715 is on the right end of this group, which also includes LST-611, LST-845 and one other. Another LST is beached on the tidal mud flats at the extreme right. Note bombardment damage to the building in center foreground, many trucks at work, Wolmi-Do island in the left background and the causeway connecting the island to Inchon. Ship in the far distance, just beyond the right end of Wolmi-Do, is USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-420027)

The tyranny of the tides and the geography made logistics supply a major challenge and placed a premium on speed. By 18 September, none of the beaches would be accessible to LSTs. At H plus 70, the Commander of Naval Beach Group, Captain Watson T. Singer, landed at Red Beach on LST-883 and took control of the offloading operations. The first echelon of eight LSTs landed at Red Beach (only small craft could reach Blue Beach). Much of the amphibious capability of the U.S. Navy had been decommissioned after World War II and even more as a result of later draconian budget cuts. Almost all the U.S. LSTs that participated in Operation Chromite had been in very poor material condition when they were hastily re-commissioned; they proved prone to breakdowns and were manned with “pick-up” crews who nonetheless did amazing work. The plan called for eight LSTs in the first echelon in the expectation that only six of them would make it. Although some were hit by mortar and rifle fire, all eight made it. Then as the tide went out, they were deliberately left stranded (and vulnerable, especially those filled with ammunition) on the mud flats while continuing to offload critical cargo. The Navy Seabees were also busy all night installing a pontoon dock on Wolmi Do, so supplies could be brought on the island and trucked across the causeway.

U.S. Navy Seabees unload supplies from trucks and load them aboard LCMs at a pontoon pier near Inchon's tidal basin, 13 October 1950. LCM closest to the camera is from USS Cavalier (APA-37). This view probably was taken during embarkation for the Wonsan operation. Sowolmi-Do island is in the center distance, with many ships anchored beyond and to the left. LSU-1160 is the nearer of two LSUs at the far left. Photographer: AF3 J.R. Ahern. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 97077)

At least four Navy coxswains were awarded the Silver Star for their valor during the landings; Seaman Chauncey H. Vogt, Seaman William H. Tagen, Engineman Fireman Richard P. Vinson, and Seaman Apprentice Paul H. Gregory.

Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, USN, Commander, Task Force 90, congratulates four Sailors who have just received the Silver Star Medal for service as coxwains of LCVP landing craft during the Inchon invasion. Taken during ceremonies on board USS Rochester (CA-124). The original photograph is dated 22 September 1950. The men are (left to right): Seaman Chancey H. Vogt, Seaman William H. Ragan, Engineman-Fireman Richard P. Vinson, and Seaman Apprentice Paul J. Gregory. Men's identities and some other information in the above caption is taken from Cagle & Manson: The Sea War in Korea, photo spread following page 364. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-423716)

Inchon After D-Day – 16 September 1950

With the early morning tide on 16 September, all eight LSTs retracted and nine more were run up on the beach. This was repeated on the late afternoon tide. Also on the 16th, heavy cranes were landed on Wolmi Do. By 2100 16 January, 15,000 personnel and 1,500 vehicles were ashore. On 17 September, RADM Lyman A. Thackrey on command ship Eldorado (AGC-11) arrived to take charge of port operations. All troops and vehicles in the first echelon were ashore by 18 September. By 21 September the U.S. Army 17th Infantry Division disembarked (and had to catch up to the Marines who had already taken Kimpo airfield on 17 September, and with the aid of cruiser gunfire, had fought off a North Korean tank counterattack on the airfield, and were well on their way to Seoul). By 21 September, the Navy force had put 53,882 personnel, 6,629 vehicles, and 25,512 tons of cargo ashore at Inchon. The Marines wasted no time in bringing in aircraft from Japan to Kimpo by 21 September, which included F4U Corsairs of VMF-221, and the F7FN Tigercat twin-engine night fighters of VMF(N)-542 (which were too big to operate from the escort carriers and had remained in Japan to this point). Marine Corsairs and helicopters off Sicily and Badoeng Strait continued to provide close air support to the rapid Marine advance. In the two days following the Inchon landing, the Marines suffered 222 casualties, including 22 killed, two missing, and two died of wounds. North Korean casualties were estimated at 1,350 plus another 300 who surrendered.

North Korean Anti-ship Strike – 17 September 1950

At 0550 on 17 September, just before dawn, two North Korean aircraft came out of nowhere, and initially thought to be friendly, attacked the heavy cruiser Rochester (still VADM Struble’s flagship) and British light cruiser HMS Jamaica while both ships were anchored in the fire support area. One Illyushin Il-2 Shturmovik ground attack aircraft (and probably the greatest tank-killer of all time, in Soviet hands during World War II) escorted by one Yak-9 piston-engine fighter rolled in on Rochester. Only a Sailor on sentry duty on the stern managed to get a shot off with his rifle before the Il-2 dropped four 100-pound bombs, straddling Rochester with near misses. One of the bombs hit Rochester’s aircraft crane on the stern but failed to detonate. The Il-10 looped back and strafed Jamaica, killing one sailor and wounding two, before it was shot down by Jamaica’s antiaircraft fire. This was the only enemy aircraft downed by naval anti-aircraft fire during the Korean War. (Accounts vary on this event, and I haven’t been able to reconcile them. Some accounts say it was two Yaks (not a Yak-9/Il-2 pair). Some accounts say both aircraft dropped bombs, as many as seven. Some accounts say the bomb that hit the crane was not a dud; it was just deflected by the crane and then exploded. What does seem apparent is that had the bomb not been deflected (or a dud) it would likely have hit the gasoline storage area in the hanger, resulting in serious damage and fire. An abandoned Il-10 was subsequently found at Kimpo airfield a few miles inland from Inchon, which may have been the origin of the attack.

Battleship USS Missouri (BB-64) and Diversions in Support of the Inchon Landing – 13-16 September 1950

Naval bombardments on the east coast of South Korea continued in the day prior to and during the Inchon landing in order to provide a diversion and to support a planned breakout of the Eighth Army from the Pusan Perimeter, intended to coincide with the Inchon landing.

On 14 and 15 September, heavy cruiser Helena and destroyer Brush, under the command of RADM Charles Clifford Hartman (CTG 95.2), bombarded targets near Samchok, midway between Pohang and the 38th parallel. This action provided a diversion supporting the ROK recapture of Pohang.

On 15 September, the North Koreans at Samchok got a rude surprise when the battleship Missouri, escorted by destroyer Maddox, fired her guns in anger for the first time since World War II. Of 23 active U.S. battleships at the end of World War II, Missouri was the only one still in commission in the summer of 1950. Assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, she had run hard aground on Thimble Shoal in Hampton Roads on 17 January 1950 and had not been refloated until 1 February. She was scheduled to conduct a midshipman cruise before she too would be decommissioned. Missouri departed Norfolk on 19 August and arrived near Japan on 14 September, becoming the flagship for RADM Allen Edward Smith, Commander UN Blockading and Escort Force (TF-95). Proceeding immediately into action in Korea, Missouri fired 52 High Capacity (HC) shells, destroying a railroad bridge and damaging another.

On 15 September 1950, another diversion attempt in support of the Inchon landing did not go well. The U.S. Eighth Army (Pusan) attempted to land 700 South Korean guerillas on the east coast of Korea north of Pohang using a South Korean merchant LST. The force went ashore and met heavy resistance, including North Korean tanks. Although destroyer-escort Endicott (DMS-35) silenced the tanks, the guerillas were driven back aboard the LST, which then broached and was driven aground. Endicott provided covering fire for the trapped guerillas until relieved by heavy cruiser Helena and destroyer-minesweeper Doyle (DMS-34), which provided extensive fire support to keep the North Koreans at bay. The guerilla force was finally rescued on 19 September.

Troops unload landing craft at Inchon's Red Beach on 18 September 1950, three days after the initial landings there. The LCVP in the center is from USS Alshain (AKA-55). Wolmi-Do island is in the background. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-467293)

Advance Toward Seoul and Pusan Perimeter Breakout – 18-28 July 1950

By 18 July, the Marines had advanced beyond the range of destroyer gunfire and would shortly be out of cruiser range. Nevertheless, naval gunfire continued to be called in for several days on isolated North Korean pockets that had been bypassed. Once the 7th Infantry Division was a shore by 18 July, Major General Almond assumed command of the ground campaign. VADM Struble and many of the ships remained in the area for several more days “in the interest of inter-service comity.”

After two months of barely hanging on to the Pusan Perimeter, the U.S. Eighth Army had been sufficiently supplied with reinforcements and ammunition (by sea) to go on the offensive and break out of the perimeter. Although the North Koreans had been on the attack as late as 5 September, they had suffered very high casualties and their supply lines had been severely disrupted by air attacks from Japanese-bases and carrier aircraft, as well as naval shore bombardment (especially along the east coast). On 16 September, the Eighth Army launched their major attack, which immediately bogged down, conjuring déjà vu of Anzio where the land offensive was unable to link of with the amphibious landing force for four months. Seeing this, General MacArthur directed preparations for another amphibious landing at Kunsan. Kunsan was on the west coast of South Korea, south of Inchon, but closer to the Pusan Perimeter. The fast-transport Horace A. Bass had previously conducted a reconnaissance of Kunsan, and COMNAVFE already had a plan (originally as a preferred alternate to Inchon). However, North Korean resistance began to crumble and the Eighth Army began to advance to the northwest toward Inchon. ROK Army I Corps units recaptured Pohang on 17 September and advanced up the east coast road, with the aid of 298 16-inch shells from Missouri. Once the ROKN I Corps got rolling, however, fire support was rarely needed as the North Koreans were soon in headlong retreat.

On 19 September, Missouri arrived on the west coast of Korea near Inchon, where her long-range guns were intended to be used to interdict the Seoul-Wonsan railroad over 25 miles away, but forces on the ground moved too fast. Despite this, the North Koreans succeeded in getting about 6-7000 reinforcements from first line units into Seoul to augment the 10,000 original defenders. By 20 September, the Marines led the way across the Han River (the major river running through Seoul). On 21 September, the two Marine squadrons just arrived at Kimpo airfield (only ten miles behind the lines) immediately joined with the two Marine squadrons on escort carriers Sicily and Badoeng Strait in providing effective close air support. However, by 22 September, North Korean resistance in the outskirts of Seoul stiffened and Marine and Army casualties began to mount.

Among the casualties were Navy Hospital Corpsmen, who performed with great valor. One of those wounded was Chief Hospital Corpsman Wayne D. Austin who was awarded the Navy Cross. “The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Chief Hospital Corpsman Wayne D. Austin, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving as a Corpsman attached to the First Battalion, Fifth Marines, FIRST Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against enemy aggressor forces near Seoul, Korea on 22 September 1950. At approximately 1645 the battalion aid station and supply dump was brought under heavy fire by enemy artillery and mortar shells, killing 7 and wounding 20 Marines. Chief Hospital Corpsman Austin, while administering aid to the wounded Marines, was severely wounded in the face, right shoulder, left arm, chest, thighs and suffered a fracture of the right ankle. He applied a compress to his ankle to partially control hemorrhage and with absolute disregard for the pain and loss of blood he continued to administer aid to the wounded. Those wounded he could not reach were given aid by the uninjured who he instructed as he moved among the wounded. He then assisted the organization of an evacuation party and helped load the Marines into ambulances. He administered treatment to ten wounded after he was wounded and it was only after all wounded had been given medical aide and evacuated that he accepted further aid and evacuation himself. Chief Hospital Corpsman Austin’s display of outstanding courage and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

25 September was a particularly bad day for the Marines squadrons on Sicily and Badoeng Strait and at Kimpo as three squadron commanding officers were shot down. The CO of VMF-214 on Sicily, Lieutenant Colonel Walter E. Lischeid, was over Seoul when his F4U Corsair took a direct hit from antiaircraft fire and then crashed and exploded; his remains were not recovered (he was awarded three Distinguished Flying Crosses, one in action against the Japanese in World War II and two in Korea).

Also, on 25 September, Major General Almond declared the Seoul had been recaptured, which came as a surprise to the Marines who had just entered the city and were engaged in house-to-house fighting until 28 September, when North Korean resistance finally collapsed and organized defense ceased. The Marines suffered 2,301 casualties in the recapture of Seoul.

On 25 September, with resistance collapsing in the southern part of South Korea, the North Korean high command issued a general withdrawal order that quickly turned into a route as North Korean units disintegrated and scattered through the hills. However, instead of bypassing Seoul, General MacArthur honored his promise to South Korean President Syngman Rhee to recapture Seoul as soon as possible. However, by doing so, the escape route for North Korean forces to the South was not completely closed off. Although 30-40,000 North Koreans in the south would be killed and 135,000 would be taken prisoner, about 30,000 made it back north to reconstitute for later operations.

Senior U.S. commanders assembled for the formal ceremonies in which General of the Army Douglas MacArthur returned the capital city to the Republic of Korea government, 29 September 1950. Those present are (from left to right, facing camera): Major General Oliver P. Smith, USMC, Commanding General, First Marine Division; Major General David G. Barr, U.S. Army, Commanding General, Seventh Infantry Division; Brigadier General Thomas J. Cushman, USMC, commanding forward echelon, First Marine Air Wing; and Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, USN, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Far East. Photographed by Sgt. Ed Barnum, USMC. U.S. Marine Corps Photograph in the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 96379)

USS Brush (DD-745) Mine Strike – 26 September 1950

On 23 September 1950, Commander Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE) received intelligence reporting that the North Koreans had laid 3,500 sea mines to date. Although a few mines had been found at Inchon, this number vastly exceeded any previous estimates, as well as the paltry U.S. and Allied minesweeping capability at the time. The severe implications of this reporting quickly became apparent.

On 26 Sept, destroyer Brush was shelling North Korean targets in the vicinity of Tanchon (on the east coast of North Korea midway between Wonsan and the Soviet border) in company with light cruiser Worcester (CL-144) and destroyer Maddox. At a speed of 20 knots, Brush hit a mine that exploded amidships, causing extensive damage and breaking her keel. Nevertheless, her damage control teams prevented the loss of the ship. Thirteen crewmen were killed and 31 injured. Five men were blown overboard; one was saved by a raft dropped from an Air-Sea Rescue aircraft, while Fireman E. N. Mitchell managed to swim two miles to an island, where he was later rescued by Maddox. Worcester stood by Brush until salvage and rescue ship Bolster (ARS-38) arrived to take Brush in tow to Sasebo. Following temporary repairs, Brush returned to Bremerton under her own power, was fully repaired and returned to action on Korea in February 1952. Brush later made three Vietnam War deployments before finishing her career as Hsiang Yang in the Taiwan Navy.

For their actions in flooded, burning, and smoke filled spaces during the mine strike on Brush, Ensign Charles W. Cole, Sonarman First Class John B. Freeman, and Boatswain’s Mate First Class Thelbert L. Metheny were awarded the Silver Star.

On 28 September, the ROKN small minesweeper YMS-509 hit a mine on the south coast of Korea that severely damaged the bow, but did not seriously injure any crewmen; the ship survived to reach the base at Chinhae.

Following the Inchon landing, United Nations surface forces began attacking targets along the North Korean coast that extends west of Seoul. On 27 September 1950, light cruiser Manchester and four destroyers bombarded positions west of the North Korean port of Haeju, supported by airstrikes from Boxer, in order to deceive the North Koreans into thinking another landing was imminent. On 29 July, HMS Ceylon put a landing party ashore on the island of Taechong Do that discovered a previously reported North Korean troop concentration had departed. By 4 October, there were no more targets in the Inchon/Seoul area in range of naval guns.

USS Mansfield (DD-728) Mine Strike – 30 September

On 29 September, Commander Fleet Air Forces Japan (COMFAIRJAP) initiated special daylight airborne mine reconnaissance missions along the coasts of Korea, including extensive use of helicopters.

On 26 September 1950 the heavy cruiser Helena, with CTG 95.2 embarked, departed Sasebo Japan for the east coast of Korea in company with destroyers Mansfield and Lyman K. Swenson. En route to station, the group rendezvoused with the badly damaged destroyer Brush (mined on 26 September) being towed by rescue and salvage ship Bolster and escorted by light cruiser Worcester and destroyer De Haven. Over the next three days the Helena group joined with destroyers Thomas and Maddox (DESDIV 92 embarked) to interdict coastal shipping and conduct night shore bombardments, made difficult by the order to remain outside the 50-fathom curve following the mining of Brush. At 1230 30 September, Mansfield and Lyman K. Swenson were ordered to steam 60 miles north to a site where a USAF B-26 bomber had crashed in the water just outside the North Korean port of Changjon (about halfway between the 38th parallel and Wonsan). At 1450, Mansfield arrived on the scene and commenced searching as machinegun fire from the beach was directed at the two Search and Rescue (SAR) aircraft on scene. Although the ship was within 2,000 yards of the reported wreck site (which was in 12 fathoms of water), lookouts on Mansfield could discern no sign of the wreckage or of survivors.

At 1547 on 30 September 1950, Mansfield had backed both engines to bring way off, when a high order explosion occurred under the bow of the ship, portside just forward of the No.1 5-inch gun turret, temporarily stunning those on watch on the bridge and much of the crew. The commanding officer, Commander Edwin H. Headland, Jr., ordered all-back full and Mansfield backed four miles to where Swenson had been standing off providing overwatch. Damage control teams were able to establish watertight integrity at frame 48. The hole below the waterline was described as “big enough to drive a city bus through,” which appears an accurate description based on photos. Somewhat miraculously no one but the ship’s mascot dog, “Pohang,” was killed, although 28 were wounded, seven seriously.

After transferring the seriously wounded to Helena, Mansfield steamed at 8 knots to Sasebo, where 65 feet of her damaged bow were removed and replaced with a temporary bow. Mansfield and Brush then proceeded together across the Pacific averaging less than 3 knots due to heavy seas, arriving at Bremerton on 23 December 1945, the first battle-damaged ships to arrive on the west coast since World War II. Gunners Mate Second Class William L. Corcoran was awarded a Silver Star for his actions in saving incapacitated and unconscious crewmen from the chief’s mess and lower handling room before they would have been killed by flooding or toxic smoke. Lieutenant Commander Chester O. Hickey, Material Officer for DESDIV 9, who was aboard Mansfield, was also awarded a Silver Star for his actions following the mine detonation. Mansfield would return to action in Korea in late 1951 and would also make multiple deployments to Vietnam, where she was hit by North Vietnamese shore battery fire on 25 September 1967, with one killed and 19 wounded.

Opening of Wonsan, October 1950. USS Merganser (AMS-26) tied up to USS Conserver (ARS-39) in Wonsan Harbor, Korea. Photographed by AFAN W.C. Newbill. The original photo is dated 23 October 1950. Note navigation bouy on Conserver's after deck and ships in background, including another AMS and a high-speed minesweeper (DMS). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-422161)

USS Magpie (AMS-25) Sunk by Mine -1 October 1950

At 1 October 1950, small minesweeper Magpie was operating in concert with her sister Merganser (AMS-26), off Chusan Po, on the east coast of South Korea just north of Pohang, trailing her sweep gear in the water. Without warning, Magpie struck a mine, blew up, broke in two amidships, and sank in minutes, with a loss of 21 crewmen missing, including the commanding officer, Lieutenant (junior grade) Warren R. Person, along with Ensign Robert E. Wainwright. Merganser rescued twelve survivors. Air search revealed two mines, and subsequent sweeps found a cluster of three 1,000-pound mines. None of those lost were ever found except for Ensign Robert W. Langwell, whose body was recovered in 2009 by the ROK Ministry of National Defense Agency for Killed in Action Recovery and Identification (MAKRI). Langwell’s body had been caught in a fisherman’s net and buried ashore by villagers during the war. Langwell was reburied at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors in 2010.

Also on 1 October 1950, near Mokpo in southwest South Korea, ROKN small minesweeper YMS-504 hit a mine with her starboard propeller, which caused two other mines nearby to sympathetically detonate. Despite loss of her engines and significant hull leakage, YMS-505 survived with only five casualties.

A Vought F4U-4B Corsair, of Fighter Squadron 113 (VF-113) from USS Philippine Sea (CV-47), flys combat air patrol over U.S. warships and U.N. shipping in Inchon anchorage, South Korea, 2 October 1950. Wolmi-Do island is in the right center distance, with Inchon city beyond to the right. USS Missouri (BB-63) is immediately below the Corsair. Among the other ships present are troop transports (AP), amphibious ships (AGC, APA, APD and LST), a hospital ship (AH) and many merchant cargo vessels. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 97076)

USS Perch (ASSP-313) First and Last Raiding Mission – 1-2 October 1950.

On 23 September 1950, submarine Segundo (SS-398) conducted a special reconnaissance mission along the northeast coast of North Korea in advance of a special operations mission to be conducted by transport submarine Perch (ASSP-313), converted in 1948 from a fleet submarine. This followed a previous submarine reconnaissance mission in the same area by Pickerel (SS-524) in August. Perch departed Japan on 25 September with a 67-man team of the 41st (Independent) Commando Royal Marines. Lieutenant Commander R.D. Quinn was in command of Perch, while Colonel Douglas Drysdale, Royal Marines, was in command of the British commandos. The mission was to destroy a section of the railroad line from Vladivostok in the Soviet Union to Wonsan, the destruction of which would cause supplies from the Soviets to be transported a much farther way around through Manchuria. The mission was complicated by new orders for Perch to remain outside the 50-fathom curve, which would require a much longer run by the inflatable boats.

Perch’s mission was first scheduled for the night of 30 September-1 October, but when Perch surfaced 4 NM from the shore and launched a 24-foot wooden skimmer from the shelter on the deck, the boat’s outboard motor wouldn’t start. In the time it took to fix the motor, lookouts noted clear indications that Perch had been detected and that the commandos would have gone into a well-prepared ambush. The mission was scrubbed. The plan was quickly readjusted to include U.S. surface ships in the area, and another target area along the rail line selected.

On the night of 1-2 October, the destroyer Herbert J. Thomas conducted a diversionary bombardment that attracted the attention of a North Korean patrol boat that had been observed the night before in the area of the originally planned operation. Destroyer Maddox provided overwatch close enough to provide gunfire support if necessary but not so close as to give away the Perch when she surfaced. Once on the surface, Perch inflated seven rubber boats and launched the wooden skimmer. On the way in, two inflatable boats took up lookout positions on the flanks, while the others proceeded to the shore, including one filled with explosives and mines. It took an hour for the boats to reach shore and, once ashore, the commandos were quickly counter-detected by North Korean sentries, resulting in several skirmishes. Nevertheless, the commandos proceeded to plant pressure mines in two railroad tunnels and large amounts of explosive in a culvert between the tunnels. The intent was for the explosives in the culvert to cause an avalanche that would block the railroad tracks, and when the North Koreans sent repair cars they would detonate the pressure mines in the tunnels, destroying the repair cars and blocking the tunnels. At 0100, the commandos blew up the culvert with the desired effect, blocking the tracks. As the commandos were re-embarking the inflatable boats, one commando was hit and killed by rifle fire. A subsequent explosion was heard from Perch, assessed to be a mine in a tunnel detonating.

This would turn out to be the first and last such mission for Perch during the Korean War because she lacked mine detection sonar. (Sufficiently upgraded, she would conduct similar missions during the Vietnam War). Lieutenant Commander Quinn was awarded a Bronze Star, and would be the only submarine skipper in the Korean War to receive a combat award. The U.S. also awarded a Silver Star to Colonel Drysdale (who was surprised by U.S. generosity with medals) and also a posthumous Silver Star to Royal Marine Peter Jones, who was buried at sea from Perch.

Unfortunately, as many as 4,000 Soviet sea mines had already passed along the Vladivostok-Wonsan railroad line. Although Soviet pilots flying “North Korean” MiG-15 jet fighters later in the war became an open secret, what is less well known was the extent of Soviet support to North Korea in the form of sea mines. The Soviets came in early and heavy with minelaying support, providing training and the mines themselves. Soviet Navy advisors were in Korea, particularly at Wonsan on the east coast and Nampo on the west coast, and some were as far south as Inchon. Although the field at Inchon was deployed hastily and late, elsewhere the minefields were laid out by the Soviets in accordance with Soviet doctrine, honed by experience in World War II.

The Soviets provided five different types of mines to the North Koreans. Fortunately, the vast majority were standard moored contact mines (most of 1904 design, which worked just fine) and relatively few of the more advanced bottom influence mines. The most common were the M-26 and MYaM mines. The MYaM was a small moored contact mine with a 45-pound explosive charge and depth limitation of 197ft. The more dangerous M-26 moored contact mine had a 530-pound charge and depth limitation of 460-ft. The Soviets also supplied MKB moored mines, which could be either magnetic or contact, with a 510-pound charge and 385-foot depth. The KMD-500 and KMD-1000 were both bottom influence mines with 660-pound/230-ft. and 1,540-pound/655-ft. explosive charge/depth capability respectively. The North Koreans laid over 3,000 mines at Wonson alone. Using any manner of vessel, including sampans, the North Koreans laid mines at various locations all around the Korean peninsula, even to the approaches to Chinhae. From late September to mid October, 65 moored and floating mines were detected and destroyed.

On 28 September, the ROKN small minesweeper YMS-509 hit a mine on the south coast of Korea that severely damaged the bow, but did not seriously injure any crewmen, and the ship survived to reach the base at Chinhae.

UN Offensive into North Korea – October 1950

Up to this point in the war, UN forces had primarily been concerned with halting the North Korean advance and to avoid being run into the sea. The situation dramatically shifted with the stunning success of the Inchon landing and the final breakout of the Eighth Army from the Pusan Perimeter. The subsequent utter rout of North Korean forces then raised the opportunity of continuing the offensive into North Korea, not just reestablishing the pre-war border. On 29 September, General MacArthur issued a planning order for Operation Tailboard, an amphibious assault in the North Korea port city on the east coast of North Korea. While U.S. political leadership debated the wisdom of going north, South Korean forces, now on a roll, just kept going north, crossing the 38th parallel on 1 October. The same day, MacArthur issued a surrender ultimatum to North Korean forces. On 6 October, U.S. naval forces were given permission to conduct naval bombardment in support of South Korean forces moving as far north into North Korea as the ROK forces could get. On 8 October, U.S. Marine forces at Seoul left the city and re-embarked on shipping for a planned assault on Wonsan (to be covered in the next H-gram).

On 8 October 1950, aircraft carrier USS Leyte arrived from the Atlantic. Leyte returned to Norfolk from a Mediterranean deployment on 24 August and departed for Korea on 6 September, bringing the number of carriers operating in Korean waters to four U.S. Essex-class (Valley Forge, Philippine Sea, Boxer, and Leyte), two escort carriers (Sicily and Badoeng Strait), and a British carrier (HMS Theseus relieved HMS Triumph on 25 September). The three carriers of TF 77 had flown 3,330 sorties during the 13 days of the Inchon assault and advance to Seoul. Leyte’s air group included the VF-32 Swordsmen flying the F4U Corsair, with African-American aviator Ensign Jesse Brown along with squadron mate Lieutenant (junior grade) Thomas Hudner (more on Hudner and Brown in a future H-gram).

The next H-gram will cover naval operations during the landings at Wonsan, North Korea in October 1950.

Sources include: Assault from the Sea: The Amphibious Landing at Inchon, by NHHC Historian Curtis Utz: Naval Historical Center, 1994. A Study of the United States Navy’s Minesweeping Efforts in the Korean War, by Stephen D. Blanton: Texas Tech Master of Arts Thesis, August 1993. Damn the Torpedoes: A short History of U.S. Naval Mine Countermeasures, 1777-1991, by Tamara Moser Melia: Naval Historical Center, 1991. “Silently. Quickly. By Sea, in Darkness: How U.S. Submarines Helped Special Troops Destroy Enemy Supply Lines in the Korean War,” by Nathaniel Patch: Prologue Magazine, Winter 2016, Vol 48, No.4. Sources include: Attack from the Sky: Naval Air Operations in the Korean War, by Richard C. Knott: Naval Historical Center, 2002. United States Naval Aviation, 1910-2010, Vol. I, Chronology by Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015. “Korean War, U.S. Pacific Fleet Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, 25 June to 15 Nov 1950” at history.navy.mil. “Naval Battles of the Korean War,” by Edward J. Marolda, at history.navy.mil. History of United States Naval Operations: Korea, by James A. Field: U.S. Navy History Division, 1962).