H-Gram 043: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die (1)—The Ordeal of USS Franklin (CV-13), 19 March 1945

20 March 2020

Contents

Overview

This H-gram tells the story of the carrier Franklin (CV-13), which suffered the greatest damage and highest casualties of any U.S. ship that did not sink, as well as an update tracking with the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, and a reprise of my 2018 H-gram article on the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918–19.

75th Anniversary of World War II

USS Franklin (CV-13)

On the morning of 19 March 1945, the aircraft carrier Franklin (CV-13), operating 50 nautical miles off the Japanese coast, was in the process of launching a major strike against Japanese naval vessels in port Kure, Japan, when a Japanese dive-bomber dropped out of the overcast and scored two direct hits with bombs. The result was devastating as the fully fueled and armed Navy and Marine aircraft on the flight deck and hanger deck contributed to over 120 secondary explosions that turned Franklin into a raging inferno virtually from stem to stern. In probably the most heroic damage control effort in the history of the United States Navy (there are other contenders but not on this scale), Franklin’s crew saved her despite catastrophic damage. It was the worst fire that any U.S. warship ever survived. Over 800 of Franklin’s crew were killed and over 400 wounded. No ship in the history of the U.S. Navy had suffered more casualties and survived. In fact, when combined with three previous hits by bombs and a kamikaze, Franklin suffered more dead than any other U.S. ship except Arizona (BB-39) at Pearl Harbor. Nevertheless, by the next day, Franklin was once again under her own power and returned to the United States for repair.

For their valor is saving their ship, the crew of Franklin and personnel of Air Group FIVE were awarded two Medals of Honor, 19 Navy Crosses, 22 Silver Stars, 116 Bronze Stars, and 235 Letters of Commendation, along with 808 posthumous Purple Hearts and an additional 347 Purple Hearts to survivors. One of the Medals of Honor was awarded to Franklin’s Catholic chaplain, Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, for not only ministering to the dying, but for organizing and leading damage control parties in fighting fires, jettisoning live ordnance, and preventing a magazine explosion. O’Callahan was the first Catholic chaplain in any service to receive a Medal of Honor, and the first chaplain in the U.S. Navy to be so distinguished (during the Vietnam conflict, Lieutenant Vincent Capodanno was the second in the Navy). The other Medal of Honor was awarded to Lieutenant (j.g.) Donald Gary, a 30-year prior-enlisted Sailor in the engineering department, for finding an escape route and then organizing and leading over 300 men trapped below to comparative safety. Navy Crosses were awarded to the commanding officer, Captain Leslie Gehres (the first prior-enlisted “mustang” to rise to command of a carrier), along with the executive officer and the navigator among others. The skippers of the light cruiser Santa Fe (CL-60) and destroyer Miller (DD-535) were also awarded the Navy Cross for daringly bringing their ships right alongside Franklin to render assistance.

For more on the ordeal and saving of Franklin, please see attachment H-042-1.

A U.S. Navy petty officer from the U.S. Naval Advisory Group—wearing South Vietnamese naval insignia—watches closely as a South Vietnamese student assembles an M-16 rifle at the small boat school at Saigon, December 1969 (USN 1142801).

50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War

“Sojourn Through Hell”—Vietnamization and U.S. Navy Prisoners of War, 1969–70

The U.S. and South Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia in April 1970 destroyed and captured massive quantities of stockpiled North Vietnamese arms and ammunition. It also provoked intense domestic political backlash in the United States. This included massive anti-war rallies (over 100,000 in Washington, DC, and San Francisco), and student protests on campuses across the country, notably the one at Kent State in which Ohio National Guardsmen fired on student protesters, killing two of them and two more students who weren’t involved. Over the next months, about 30 ROTC buildings on campuses would be burned or bombed in protest. For much of the U.S. population, the Nixon adminstration’s stated policy of “Vietnamization” of the war couldn’t happen fast enough. Meanwhile, several hundred U.S. prisoners of war, mostly downed aviators, languished in North Vietnamese prisons, subject to brutal interrogations and torture. Of 178 U.S. Navy personnel captured during the entire course of the war, 36 died.

The severe treatment of U.S. prisoners of war became somewhat less so in the fall of 1969, due in significant part to the actions of the senior U.S. Navy POW, Captain James B. Stockdale, and the most junior Navy POW, Seaman Apprentice Douglas B. Hegdahl. Believing Hegdahl to be illiterate and “incredibly stupid,” the North Vietnamese released him as a propaganda ploy in August 1969, completely unaware that Hegdahl had memorized the names and key information of 256 American POWs. Hegdahl was ordered by senior POWs to accept early release (despite his initial refusal) in order to get this vital data back to U.S. authorities, as well as to provide detailed confirmation of the North Vietnamese use of torture, which the United States subsequently used against North Vietnam at the Paris Peace Talks.

Meanwhile, the North Vietnamese tried yet again to break the will of Captain Stockdale, who they viewed as the key leader of U.S. POW resistance to being used in North Vietnamese propaganda efforts. In September 1969, rather than risk submission in yet another round of extremely painful torture, Stockdale inflicted near-mortal wounds on himself that were intended to convince the North Vietnamese of his willingness to die before he would submit, an action for which he would be awarded the Medal of Honor after the POWs’ release in 1973. Between Stockdale’s determined resistance and Hegdahl’s embarrassing revelations, the North Vietnamese began to reach the conclusion that torture was counter-productive. Although psychological torment of the POWs, as well as occasional beatings, continued with no end in sight, deliberate torture largely ceased for the duration of the war,

For more on the Vietnamization of the war in 1969–70, the incursion into Cambodia in 1970, and the treatment of U.S. POWs, please see attachment H-043-2.

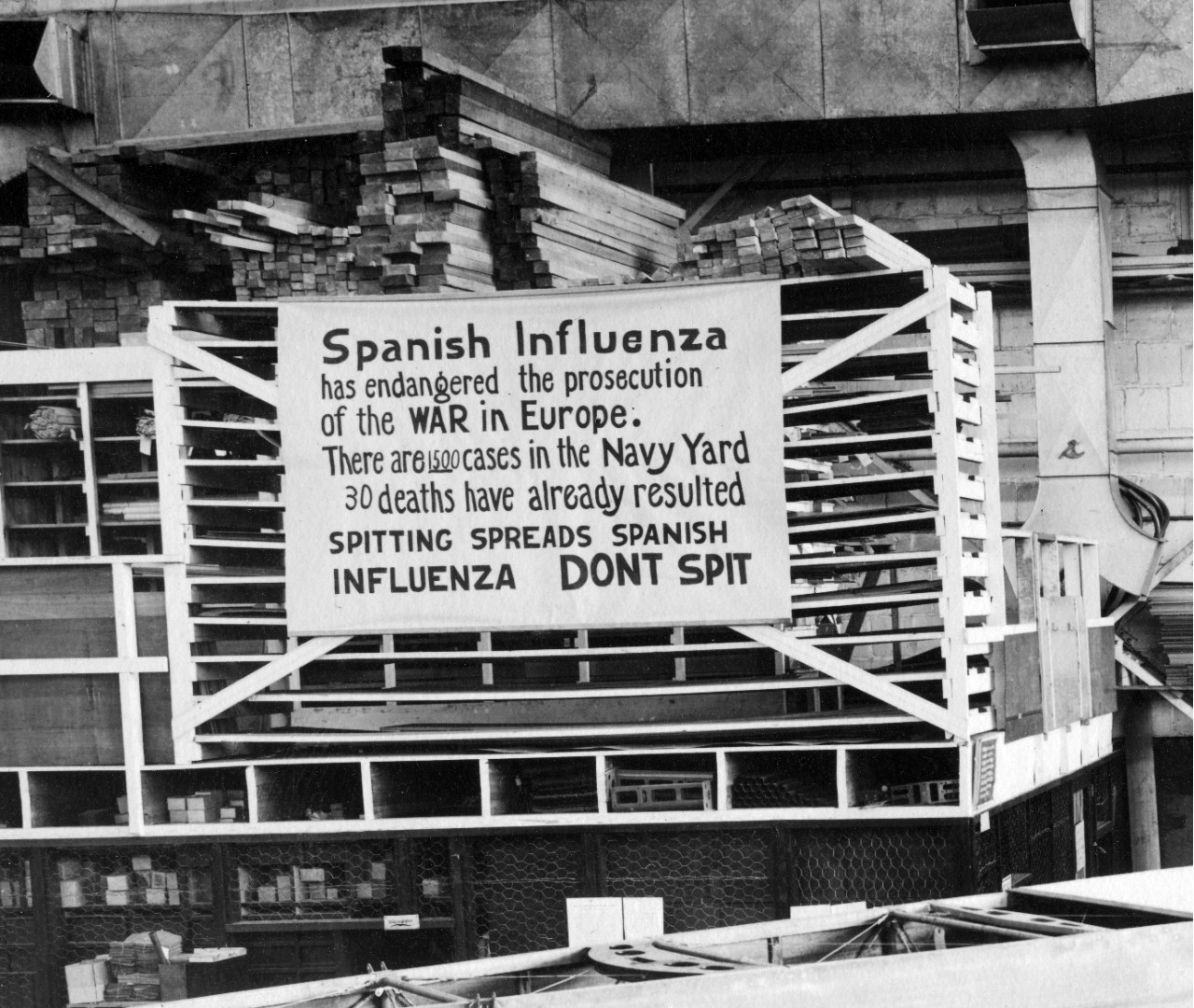

An influenza precaution sign mounted on a wood storage crib at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 19 October 1918. As the sign indicates, the Spanish influenza was then extremely active in Philadelphia, with many victims in the Philadelphia Navy Yard and the Naval Aircraft Factory. Note the sign's emphasis on the epidemic's damage to the war effort (NH 41731-A).

The Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918–19

I am also enclosing a link to the piece on the Spanish influenza of 1918–19 that I wrote in October 2018. Information on the current virus (COVID-19) should be derived from current reputable sources, and because a virus acted one way in 1918–19, it does not mean a different virus will behave in similar fashion now. The latest Navy information on the Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) may be found here. My original 2018 article, a segment of H-Gram 022, may be found here.

Nevertheless, I believe there are still a number of salient lessons from the Spanish influenza epidemic. One that I have not heard mentioned in recent days is the importance of staying in touch with those who are in home quarantine. During the 1918–19 epidemic, many people died in their homes because they could not get care in time. In many cases, these might have survived the flu with proper care, but died instead from dehydration (or even starvation), hypothermia (untended furnaces went out), or asphyxia (untended furnaces gassed them). As the epidemic peaked in the fall of 1918, it became very much an “every man for himself” environment as fear of contracting the virus overrode many people’s sense of compassion or duty. Neighbors did not help neighbors and calls for volunteers to assist the overwhelmed medical staffs went unanswered. Today, we have the advantage of widespread telephone and electronic communications to remain in touch with those otherwise isolated.

Another lesson was that viruses mutate. They can become more or less virulent over time, and they can affect different populations in very different ways. For example, during the 1918–19 epidemic, U.S. Army troops on Navy transports suffered high mortality (12,000 died in transit) whereas Navy crews on those same ships did not; to this day, no one really knows why. The first wave of the epidemic in the spring of 1918 was relatively mild, slightly worse than the normal flu except that it affected young and healthy people the most. It was the second wave of the epidemic in the fall of 1918 that was the real global killer. About 40 percent of all U.S. Sailors were infected; 121,225 Navy personnel were admitted to hospitals and 5,027 died, a mortality rate of about 4 percent (compared to 431 who died in battle during World War I). It is estimated that over 700,000 Americans died during the epidemic.

Other lessens were that the key to avoiding panic or unnecessary deaths was the timely and accurate dissemination of information, and prompt and drastic action to slow the spread of the virus. Wartime censorship resulted in additional deaths, as people were kept in the dark to avoid giving the enemy information about how bad it was. The desire to continue with “business as usual” also led to unnecessary deaths: A war bonds parade held in Philadelphia despite clear warning the virus had arrived in the city was one of the most notorious examples of a deliberate decision by community leaders that led to widespread additional and unnecessary deaths.

Back issues of H-grams may be accessed here.