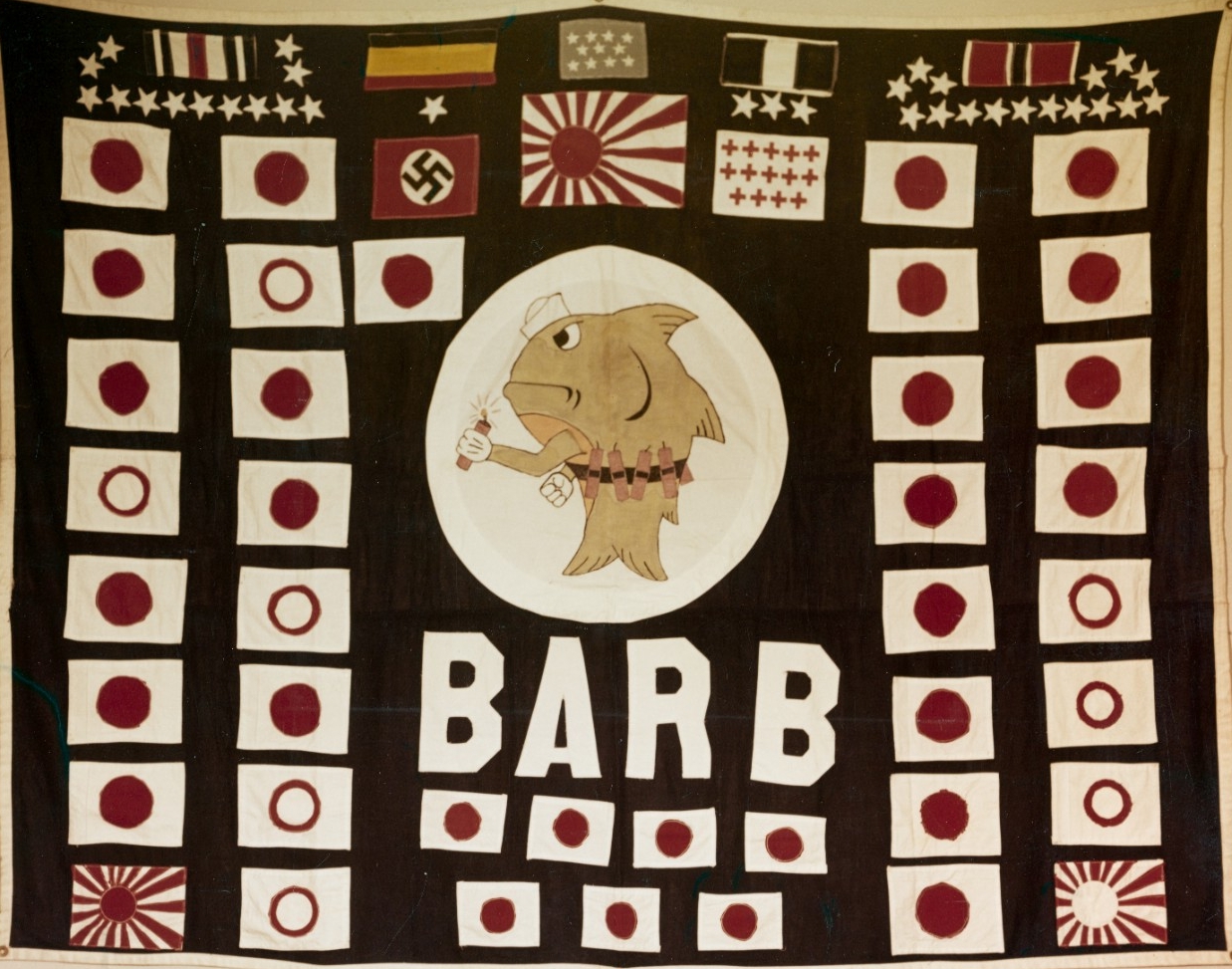

H-041-2: USS Barb (SS-220) Sinks an Aircraft Carrier, Penetrates a Harbor, and Blows Up a Train

USS Barb (SS-220 ), was commissioned on 8 July 1942, and initially assigned to Submarine Squadron 50, in which she was one of six U.S. submarines assigned to operate in the eastern Atlantic—based on a personal request from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to President Franklin Roosevelt, over the objection of Chief of Naval Operations Ernest J. King. The theory was the longer endurance of American submarines might make them useful ambushing German U-boats.

On Barb’s first war patrol, she participated in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, by providing pre-landing reconnaissance, beacon services, and landing a five-man team of U.S. Army Rangers just prior to the landings at Safi, Morocco. Barb’s next four patrols were unproductive, which was generally the case with the rest of the SUBRON 50 boats. In the spring of 1943, CNO King finally prevailed in his desire to have all U.S. submarines sent to the Pacific and, by the summer of 1943, the squadron was disbanded. One of the SUBRON 50 boats, Blackfish (SS-221 ), may have the distinction of being the only submarine to be depth-charged by three different navies: by a Vichy French destroyer off Senegal during Torch; by a German patrol boat in the Bay of Biscay (after sinking German patrol boat 408); and multiple times by Japanese ships in the Pacific. She survived them all (barely, in the case of the Germans, as she bottomed out at 365 feet).

Barb’s sixth war patrol (and first in the Pacific) along the China coast was action-packed (especially when she bottomed out at 375 feet during a Japanese attack), but was frustrating and unproductive. On her seventh war patrol, with Commander Eugene Fluckey on board as prospective commanding officer, Barb had a little more luck, sinking Fujusei Maru (which was assessed as a possible Q-ship) and participating with Steelhead (SS-280) in shelling a phosphate plant on the island of Okino Daito Jima, east of Formosa.

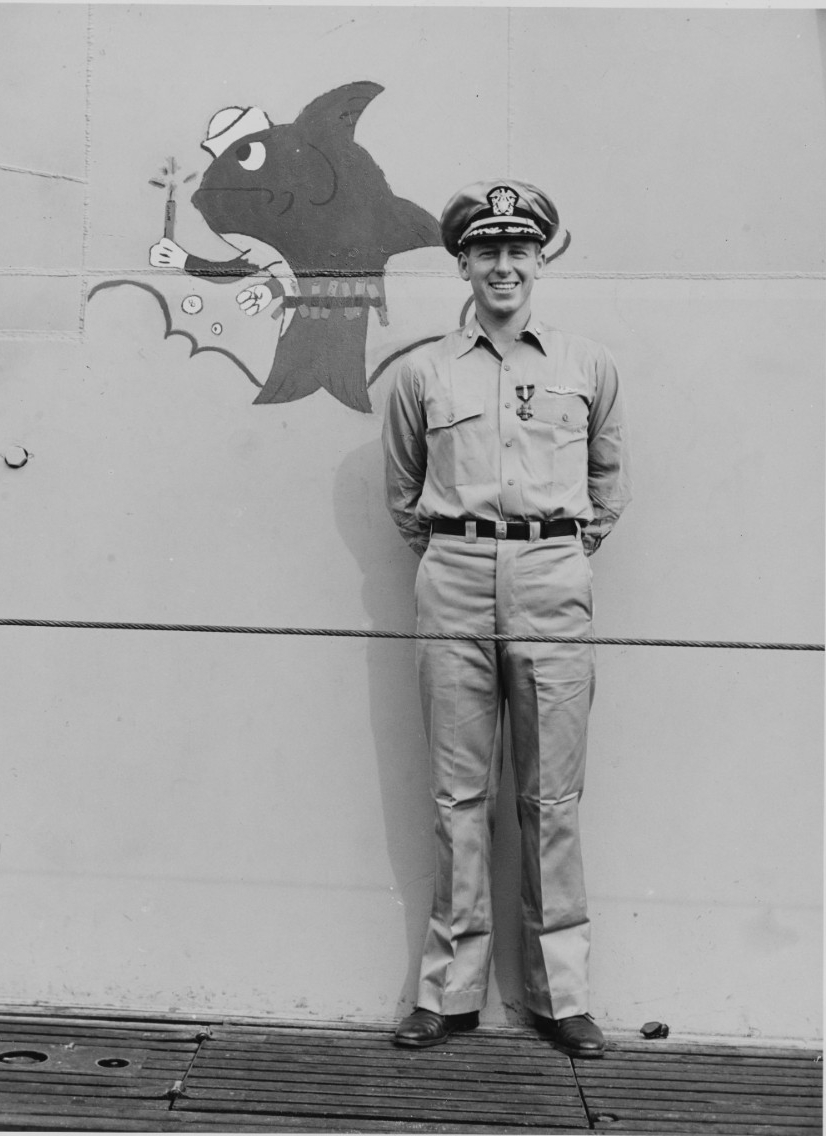

Eugene “Lucky” Fluckey (it rhymes) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1935. After initial service aboard the battleship Nevada (BB-36) and destroyer McCormick (DD-223), he transferred to submarine duty, serving on S-42 (SS-153) and Bonita (SS-165 ), including five uneventful “war patrols” defending the Panama Canal on Bonita. He assumed command of Barb in late April 1944. After the war, he went on to a very distinguished career that included personal aide to Chief of Naval Operations Chester Nimitz and command of Halfbeak (SS-352 ), Submarine Division 12, submarine tender Sperry (AS-12), and Submarine Squadron 5. He was promoted to rear admiral in July 1960, and served as commander, Amphibious Group 4, president of the Board of Inspection and Survey, director of Naval Intelligence (1966–68), and chief of the Military Advisory Group to Portugal before his retirement in August 1972. During his World War II service, he would be awarded the Medal of Honor and four Navy Crosses, making him one of the most combat decorated officers in the history of the U.S. Navy.

Eighth War Patrol

Barb’s eighth war patrol, her first with Fluckey in command, was in the Sea of Okhotsk , north of Hokkaido, between 21 May and 9 July 1944. This proved to be a very dangerous area as Herring (SS-223) was sunk just after a rendezvous with Barb in the Kuril Islands. Herring sank the Hokuyo Maru and the escort ship Ishigaki before falling victim to Japanese shore battery fire on 1 June. (Ishigaki had previously sunk U.S. submarine S-44 [SS-155] on 7 October 1943, which had in turn sunk Japanese heavy cruiser Kako in August 1942 as Kako was returning from the Japanese victory at Savo Island. Kako was the first major combatant to be sunk by U.S. submarines during the war, but by no means the last.) In addition, Golet (SS-361) disappeared on the way to the Kurils and was possibly sunk by a Japanese mine on 14 June 1944.

Despite multiple Japanese ASW attacks, Barb had a very successful patrol in the Sea of Ohkotsk, sinking five major cargo ships (for a total of 15,472 tons) and a number of trawlers and sampans. Fluckey was awarded his first Navy Cross for this patrol.

Ninth War Patrol

Barb’s ninth war patrol, from 4 August to 3 October 1944 in the South China Sea between Formosa and the Philippines, was very eventful and successful. Barb operated as part of a wolfpack (“Ed’s Eradicators”) that included Queenfish (SS-393) and Tunny (SS-282). Alerted by Ultra Intelligence, Ed’s Eradicators and another wolfpack (“Ben’s Busters”) converged on the large and heavily-escorted Convoy MI-15. Queenfish initiated the attack and sank two ships including Chiyoda Maru, which went down with 385 passengers and 15 of her crew. Then, Barb commenced an attack, sinking the cargo ship Okuni Maru (one of the most famous photos of the war) and damaging the tanker Rikko Maru, which had to be beached (some accounts credit Queenfish with this hit). Barb then maneuvered to attack Hinode Maru No. 20, an auxiliary minesweeper being used as a decoy (Q-ship). However, a bird perched on the periscope and blocked the view. Barb lowered the scope and then raised it again, but the bird perched again. Barb then lowered the scope and then raised both scopes a couple seconds apart, which fooled the bird. Barb fired three torpedoes and hit with at least two, sending Hinode Maru No. 20 to the bottom along with the commander of Mine Squadron 45. The next day, Barb was damaged by two near-miss bombs from a Japanese aircraft, but Fluckey opted to continue the mission.

On 9 and 14 September, Barb made unsuccessful attacks, including surviving being caught on the surface in the searchlight of a Japanese destroyer, which opened fire. Fluckey noted in the log, “Set new record for clearing the bridge.”

On 16 September, Barb received a message to assist in the search for Allied POW survivors of Rakuyo Maru, which had been sunk on 12 September by Sealion (SS-315). While on the way, Queenfish and Barb encountered a large Japanese convoy and attacked (Tunny had been damaged in an air attack on 31 August and was returning to port). Queenfish attacked first with no reported hits. As Barb was closing in on a Japanese tanker, Fluckey recognized that there was an escort carrier in the convoy. He maneuvered Barb so that he could fire at both the tanker and the escort carrier with the same salvo, firing all six bow tubes at the overlapping targets.

At 0034 on 17 September, the 11,700-ton tanker Azusa Maru was hit in the starboard side by two torpedoes, exploded and sank in 15 minutes with all hands. The 20,000-ton escort carrier Unyo’s sound gear detected the inbound torpedoes and she attempted to evade, but it was too late. At 0037, one torpedo hit Unyo in the engine room, another in her steering compartment, and she was possibly hit in the stern by a third. Barb attempted to bring stern tubes to bear to finish the job, but one of the Japanese escorts drove her under.

Unyo’s crew fought for hours to try to save her, and might have succeeded had it not been for the rapidly deteriorating sea conditions associated with an approaching typhoon. Unyo had survived multiple attacks by U.S. submarines, including being hit by three torpedoes (two exploded) from Steelhead (SS-280) on 10 July 1943, but not this time. By 0730, Unyo was listing badly and, at 0755, the captain gave the order to abandon ship and then chose to go down with her. Unyo suffered 26 of her crew killed, but 707 were rescued by the Japanese (there are discrepancies in how many passengers were aboard Unyo, with reports of between 200 and 800 lost, although 200 is probably more accurate).

By the afternoon of 17 September 1944, Barb and Queenfish reached the scene of the demise of Japanese convoy HI-72 at the hands on Ben’s Busters—Sealion (SS-315 ), Pampanito (SS-383), and Growler (SS-215). On 12 September 1944, Sealion had sunk Rakuyo Maru, not knowing that 1,317 British and Australian POWs were on board, while Pampanito sank Kachidoki Maru, which had 950 POWs on board. The Japanese actually rescued about 520 British POWs from Kachidoki Maru, but 431 perished (along with 53 Japanese), while 1,159 POWs aboard Rakuyo Maru were lost (350 of whom died when the lifeboats they were in were destroyed by gunfire from a Japanese ship). On 15 September, Pampanito passed through the scene of the attack, and discovered POWs clinging to wreckage. Ultimately, Pampanito, Sealion, Queenfish, and Barb rescued a total of 149 Allied POWs (with Barb accounting for 14) before high seas and typhoon winds cut short the effort. (Of note, Sealion would sink the Japanese battleship Kongo and destroyer Urakaze on 21 November 1944). Fluckey was awarded his second Navy Cross for this patrol.

Tenth War Patrol

Barb’s tenth war patrol was conducted in the heavily mined areas just south the Tsushima Strait between Korea and Kyushu from 27 October to 25 November 1944 as part of the wolfpack “Loughlin’s Loopers, which included Queenfish and Picuda (SS-382). At 0245 on 10 November, Barb’s SJ radar detected the armed merchant cruiser Gokoku Maru. At 0334, Barb fired three Mark 18 electric torpedoes. One hit Gokoku Maru just aft of the funnel and a second hit just forward of the bridge. Despite taking on a 30-degree list and losing one engine room and all electrical power, Captain Mizuno was attempting to beach his ship when Barb fired another electric torpedo that circled and missed. Fluckey closed to within seven nautical miles of Kyushu and, at a range of 1,400 yards, fired another torpedo at 0410 that sank Gokoku Maru and 326 of her crew, including Captain Mizuno.

On 12 November, Barb sank the cargo-troop transport Naruo Maru, which blew up and sank immediately, killing 490 troops and 203 crewmen. Barb also hit 5,396-ton Gyokuyo Maru, which did not sink and was finished off while under tow on 14 November by Spadefish (SS-411). (Some analyses suggests that Barb, in fact, sank Gyokuyo Maru, but I’m not going to be able to sort it out.) Fluckey was awarded his third Navy Cross for this patrol.

Eleventh War Patrol

For her eleventh war patrol, from 20 December 1944 to 15 February 1945, Barb teamed again with Loughlin’s Loopers (Queenfish and Picuda ). This time, her operating area was along the China Coast and Formosa Strait. At 1233 on 1 January, Barb came upon a Japanese picket/weather ship that had been attacked by the other two submarines with gunfire earlier in the day, but was still afloat and drifting. Barb came alongside, put a boarding party aboard, and took everything of potential intelligence value before sinking her with guns.

Aided by Ultra intelligence, commencing about 1830 8 January 1945 in the northern Formosa Strait, Loughlin’s Loopers set upon Japanese Convoy MOTA-30, consisting of nine cargo ships and tankers and four escorts transiting from Moji, Japan, to Takao, Formosa. By the next morning, the convoy and escorts were completely scattered and almost every cargo ship had been sunk, run aground, or badly damaged. In the melee, there are discrepancies as to exactly who shot whom. Barb fired three bow tubes at a large freighter and three bow tubes at a tanker, and heard four hits. The third hit caused a massive explosion that buffeted the submarine. Most accounts say these were Shinyo Maru and Sanyo Maru (however, Shinyo Maru had been sunk in 1943). Japanese records indicate Barb hit Tatsuyo Maru, which was loaded with munitions, blew up, and sank instantly with all 63 hands. The damaged Sanyo Maru subsequently ran aground and later broke apart and sank.

With her bow tubes empty, Barb was forced under by a charging escort while Queenfish and Picuda continued the attack. Barb then conducted a second and third attack, firing six torpedoes at a large passenger cargo ship, which ““disintegrated in a pyrotechnic display like a gigantic phosphorous bomb.” This was possibly Anyo Maru, which lost 138 crewmen and “many” troops, but in some accounts is credited to Picuda. The Hikoshima Maru dodged numerous torpedoes, probably some from Barb, before running aground (Barb got credit ). Barb also apparently hit Hisagawa Maru, which survived the night, was attacked the next day by aircraft, and then broke apart and sank, going down with 2,117 Japanese army personnel, 84 navy gunners, and all 86 crewmen. Somewhere in this mix, Barb was credited with causing Meiho Maru to run aground, where it was bombed by aircraft. Thus, it is possible that Barb was responsible, or partially responsible, for sinking six Japanese ships (or forcing them to beach) in one night.

For the next couple of weeks, Loughlin’s Loopers found no targets at night. Fluckey deduced that the Japanese had changed operating patterns and were anchoring in Chinese ports during the night and hugging the Chinese coast during the day. A cautious reconnaissance in shallow and mined waters along the Chinese coast proved Fluckey right and, on the night of 22–23 January, he hit the jackpot. Fluckey estimated there were two 30 ships anchored in Namkwan harbor, on the coast of China. (It was actually 11 escorts, and 16 cargo/tankers and transports of two convoys, MOTA-32 and TAMO-38.) Fluckey reasoned that he would have the advantage of darkness and surprise on the way in to the harbor, but after the attack would need to run at maximum speed on the surface for over an hour in order to reach water deep enough to submerge. Fluckey opted to attack.

At 0402 on 23 January 1945, at a range of 3,000 yards BARB fired all six bow tubes at the mass of ships in Namkwan Harbor, then turned and fired all four stern tubes, as she commenced her getaway. Fluckey initially reported observing eight hits that sank three ships and damaged three others. One of the ships was the Taikyo Maru, which was carrying ammunition, resulting in a massive explosion that sank the ship that killed 360 troops, 26 gunners, and 56 crewmen. Barb ran at over 21 knots on the surface for one hour and 19 minutes through shallow, poorly charted, and mined water to escape. Fortunately, in the chaos of the attack, the Japanese mounted no effective response.

Japanese records of this attack disappeared at some point, and the post-war Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) only gave Barb credit for sinking Taikyo Maru. However, coast-watcher reports from Naval Group China (more on them in a future H-gram) and recollections of Chinese witnesses indicate that four ships were sunk (two of them large) and three damaged, which would make Fluckey’s final claim of three ships sunk, one probably sunk, and three damaged, on the mark.

Commander Eugene B. Fluckey was a awarded a Medal of Honor for this patrol. The citation reads as follows:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of USS BARB during her Eleventh War Patrol” along the east coast of China from 19 December 1945, to 15 February 1945. After sinking a large ammunition ship and damaging additional tonnage during a 2-hour night battle on 8 January, Commander Fluckey, in an exceptional feat of brilliant deduction and bold tracking on 23 January, located a concentration of more than 30 enemy ships in the lower reaches of Nankuan Chiang (Mamkwan Harbor ). Fully aware that a safe retirement would necessitate an hours’ run at full speed through the uncharted, mined and rock-obstructed waters, he bravely ordered, ‘Battle Station—Torpedoes!” In a daring penetration of the heavy enemy screen, and riding in 5 fathoms of water, he launched the BARB’s last forward torpedoes at 3,000 yards range. Quickly bringing the ship’s stern tubes to bear, he turned loose four more torpedoes into the enemy, obtaining eight direct hits on six of the main targets to explode a large ammunition ship and causing inestimable damage by the result of flying shells and other pyrotechnics. Clearing the treacherous area at high speed, he brought the BARB through to safety and 4 days later sank a large Japanese freighter to complete a record of heroic combat achievement, reflecting the highest credit upon Commander Fluckey, his gallant officers and men, and the United States Naval Service.”

After receiving his Medal of Honor, Fluckey gave a signed card to each member of the crew that read as follows:

As Captain it has been an outstanding honor to be your representative in accepting the Congressional Medal of Honor for the extraordinary heroism above and beyond the call of duty which you and every officer and man in the BARB displayed. How fortunate I am, how proud I am, that the President of the United States should permit me to be the caretaker of this most distinguished honor which the Nation has seen fit to bestow upon a gallant crew and a fighting ship…the “BARB.”

Sincerely,

Eugene Fluckey

Barb was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for her eighth, ninth, tenth, and eleventh war patrols.

Twelfth War Patrol

Following a major overhaul at Mare Island that included the installation of a 5-inch rocket launcher at Fluckey’s request, Barb conducted her twelfth war patrol between 8 June and 2 August 1945, returning again to the Sea of Okhotsk and reaching her assigned area on 21 June. There, she sank two small sailing ships with gunfire. On 22 June, Barb surfaced one mile off the town of Shari, Hokkaido, and fired a barrage of 12 rockets at factories in the town center. These caused damage but no fires. Barb thus became the first submarine to employ rockets against a shore installation, in this case, successfully (Barb was also the only submarine to fire rockets in World War II.) The Japanese thought they were under air attack, and Barb escaped to safety. The next day, Barb sank a trawler and took a Japanese prisoner.

The following actions took place on or around Sakhalin Island, now part of Russia. (After the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, the island of Sakhalin was divided between Russia—the northern half—and Japan—the southern half. In August 1945, at the very end of World War II, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, invading Japanese-occupied Manchuria and capturing southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands.)

On 2 July 1945, Barb surfaced 1,100 yards off Kaihyo To Island (just off Sakhalin) and destroyed a radar station, radio station, buildings, boats, and supplies with gunfire. An attempt to put a landing party ashore was aborted when four pillboxes were observed overlooking the harbor. On 3 July, Barb fired rockets at Shikuka air base on Sakhalin; 12 rockets exploded in a concentration of buildings. Barb also sank an unknown probable army cargo ship; although she wasn’t given official credit, the evidence looks pretty solid. Barb sank two more cargo ships on 5 and 10 July, and, on 18 July, sank coastal defense vessel 112 (a small 940-ton frigate).

On 19 July 1945, Fluckey observed a train travelling on tracks along the Sakhalin coast and hatched one of the most daring operations in the annals of U.S. submarine warfare. For three nights, Fluckey observed the trains in order to determine the schedule. On the night of 22–23 July, a landing party of eight volunteers went ashore to plant explosives on the train tracks. The landing party had difficulty making its way across the terrain, and had to hide in the bushes as the first train passed only a few feet away before the 55-pound charge could be set. As the landing party was paddling back to Barb, the next train came by, detonating the explosives. Pieces of the locomotive flew 200 feet into the air, and 12 freight cars, 2 passenger cars, and a mail car derailed and piled into a twisted mass. Japanese propaganda claimed that civilian passengers were killed, but intelligence indicated that trains traveling at night carried troops. This is claimed as the only ground combat on the Japanese Home Islands during World War II, and though Sakhalin is not now a Japanese island, in 1945, technically it was a “Home Island.”

On 24 July 1945, Barb conducted three rocket attacks on a factory at Shiratori, Sakhalin Island. This was followed on 25 July by a shore bombardment of a cannery at Chiri, Sakhalin. Also on 25 July, Barb conducted her last rocket attack, on factories at Kashiho, Sakhalin. On 26 July, Barb bombarded Shibetoro on the island of Kunishiro (the southernmost in the Kuril Islands), destroying a lumber mill and sampan-building yard. She then set a trawler on fire and rammed it to finally sink it, while capturing three more Japanese prisoners. Barb arrived at Midway on 2 August 1945 and was there when the war ended.

Fluckey was awarded his fourth Navy Cross, and Barb received a Navy Unit Commendation for her twelfth war patrol. Fluckey was particularly proud of the fact that no member of Barb’s crew received a Purple Heart during the war.

Sources include: Thunder Below! The USS Barb Revolutionizes Submarine Warfare in World War II, by RADM Eugene B. Fluckey, University of Illinois Press, Champaign, IL, 1992; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) at history.navy.mil; and, for Japanese ships, combinedfleet.com.