H-010-2: The Battle of the Eastern Solomons, 23–25 August 1942

H-Gram 010, Attachment 2

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

September 2017

The commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, immediately grasped the strategic significance of the American landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August 1942. Despite his staggering losses at the Battle of Midway on 4 June, Yamamoto quickly set in motion a major operation to counter the U.S. landings. While Rear Admiral Mikawa dealt a devastating blow to Allied naval forces off Guadalcanal at the Battle of Savo Island in the pre-dawn hours of 9 August using cruiser forces at hand, major elements of the Japanese navy began assembling at the major base at Truk, several hundred miles north of Guadalcanal, with the intent to rapidly eject the Americans from Guadalcanal. This force would consist of two fleet aircraft carriers, two medium carriers, one light carrier, four battleships, 16 cruisers, and 30 destroyers, outnumbering U.S. naval forces in the Solomons area in every category except fleet carriers (two Japanese to three U.S. fleet carriers). Unfortunately for the Japanese navy, the Japanese army did not share Yamamoto’s sense of urgency, remaining supremely overconfident in their ability to kick the Americans off the island whenever they got around to it. Challenges in getting the Japanese army to commit forces to the battle on Guadalcanal delayed the fleet’s action until late August.

The Japanese made numerous organizational, tactical, and operational security changes following their defeat at the Battle of Midway. However, the unexpected rapidity of U.S. offensive action in the Solomon Islands caught the Japanese by surprise, and many of the changes had not been fully implemented, nor in many cases had the Japanese been able to conduct sufficient training in new tactics and procedures. The two remaining Japanese fleet carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, were reorganized into Carrier Division 1 (since Akagi and Kaga had been sunk at Midway). The light carrier Ryujo was also added to CARDIV 1, with a heavy complement of 24 Zero fighters and nine Kate torpedo bombers, with the intent that Ryujo would supply the fighters for fleet defense (and torpedo bombers for a last-ditch reserve strike), while the fleet carriers focused exclusively on engaging and defeating U.S. carriers. In this way, the Japanese hoped to avoid the conflicting mission requirements that led them to disaster at Midway. Another major change in tactics was that the Japanese now intended to hold all their torpedo bombers in reserve, and wait for the dive bombers to soften up the targets before committing the more vulnerable torpedo bombers (losses among those torpedo bombers that actually reached the U.S. carrier Yorktown [CV-5] at Midway were almost as devastating as those suffered by the American torpedo bombers). The Japanese still adhered to their doctrinal approach to conduct strikes with combined carrier air groups (i.e., aircraft integrated from two carriers into a single strike package), which allowed for more rapid launch, assembly, and push to target than the American approach of independent strike packages by different carriers, that might (or might not) be loosely coordinated. Another revised tactic was for Japanese battleships and cruisers to operate a considerable distance ahead of the carriers to provide early warning, diversion, and increased possibility of closing for surface action with U.S. forces; the downside was that these forward forces were therefore more vulnerable to air attack. However, the Japanese reasoned that any bomb that hit a battleship or cruiser was a bomb that didn’t hit an aircraft carrier, and the battleships and cruisers could absorb the damage much better than a carrier—and, the Japanese were basically right. Also, in a first for the Japanese, the Shokaku carried radar, which at one point in the battle detected U.S. aircraft at 97 nautical miles, the best performance by any radar on either side.

The major changes in organization, changes to the JN-25 code, call-sign changes, better communications security, and other measures adversely affected the ability Commander Joseph Rochefort’s code breakers and communications-traffic analysts, and of Admiral Nimitz’s intelligence officer Commander Eddie Layton, to accurately predict Japanese actions and timing. It was apparent that the Japanese were forming up a very large force for operations in the vicinity of Guadalcanal, but delays on the Japanese side adversely affected intelligence predictions of the timing. Naval Intelligence also had a very difficult time locating the Shokaku and Zuikaku, holding them still in home waters even after they had departed for Truk, and only concluding they had arrived at Truk the day before the battle (when they had already left Truk and were en route to what would be the battle area northeast of Guadalcanal). The commander of the U.S. carrier task force (TF 61), Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, knew from intelligence that a major Japanese push was coming around 23–25 August, but had no firm estimate on the presence of Japanese carriers until the eve of battle—and only after he had released the carrier Wasp (CV-7) to go south to refuel, taking a third of Fletcher’s strike capability with her. Many historians (in addition to CNO King at the time) have uncharitably commented that Fletcher never passed up an opportunity to refuel, whether needed or not. However, in this case Fletcher was directed to do so by the South Pacific Area commander, Vice Admiral Ghormley, who was making decisions based on the same ambiguous intelligence as Fletcher. The Japanese also had great difficulty trying to locate the U.S. carriers; usually their best indication was when a reconnaissance aircraft ceased reporting, which meant it had probably been shot down. Bad weather also played havoc with both sides during the course of the battle, several times preventing Japanese land-based aircraft from the northern Solomons from flying missions to Guadalcanal in support of the Japanese carrier operations.

Actions on 23 August

At 0950, a U.S. Navy Catalina flying boat spotted a Japanese convoy north of Guadalcanal heading toward the island. This convoy was under the command of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka (whose name would become indelibly associated with the “Tokyo Express”) and consisted of his flagship, the light cruiser Jintsu, eight destroyers, and three troop transports carrying 1,500 troops of Colonel Ichiki’s second echelon (Ichiki himself and his first echelon had already been virtually annihilated at the Battle of Tenaru River on Guadalcanal on 21 August), and the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force. Upon being sighted, Tanaka reversed course. Search planes from USS Enterprise (CV-6) sighted three Japanese submarines during the day, indicative of a screen ahead of a Japanese force movement.

Fletcher held back, awaiting reports from any scout planes on the presence of Japanese carriers, but none were located. Finally Fletcher directed a strike on Tanaka’s convoy, and, at 1510, the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) launched a 37-plane strike (31 SBD Dauntless dive bombers and six of the new TBF Avenger torpedo bombers, the latter from the reconstituted Torpedo Squadron 8; these were aircraft that had arrived at Pearl Harbor, but had not made it to the USS Hornet [CV-8] or Midway Island before the battle commenced). The strike, led by Saratoga Air Group commander Commander Harry D. Felt, encountered very bad weather, but pressed on despite severe buffeting and extensive periods of near-zero visibility. Commander Felt later expressed extreme satisfaction with the flying discipline of his aircrews when they emerged through the weather in good order formation. However, by this time, Tanaka was nowhere to be found. After a fruitless search, with light waning, and the prospect of having to fly back through the weather to the Saratoga, Felt opted to recover on Henderson Field, where Navy pilots got to enjoy a mostly sleepless night, including being fired upon by the Japanese destroyer Kagero. Marine aircraft from Henderson Field had also unsuccessfully attempted to locate Tanaka’s convoy. Too late in the day, U.S. search planes located elements of Vice Admiral Kondo’s advance force of battleships and cruisers, operating ahead of Vice Admiral Nagumo’s as-yet-undetected carrier force.

The Carrier Battle, 24 August

Before dawn on 24 August, Nagumo detached the light carrier Ryujo from the main carrier force to provide air cover for Tanaka’s convoy. At 0946, a PBY sighted the Ryujo. Having sent a large strike force on a wild-goose chase the day before, which was still in the air returning to the Saratoga from their night ashore on Guadalcanal, Fletcher held back, awaiting sighting reports on Japanese fleet carriers. Fletcher did not want a repeat of the Battle of Coral Sea, where he had learned the location of the same Shokaku and Zuikaku only after he had already committed the entire air groups of both his carriers against the light carrier Shoho. Commander Felt’s strike group began recovering on Saratoga at 1105. At 1128, Fletcher received a second location report on the Ryujo. He ordered more search aircraft aloft, but still held back from committing a strike on Ryujo. At 1213, Saratoga Wildcats shot down a Japanese land-based Emily four-engine reconnaissance seaplane, while at 1228, Enterprise Wildcats destroyed a land-based twin-engine Betty bomber. U.S. radio intelligence reported that neither aircraft had gotten off a contact report, but Fletcher made the assumption they had.

With no sighting reports of U.S. carriers, Nagumo was in even more of the dark than Fletcher. So at 1230, Ryujo commenced her secondary mission, launching 15 Zero fighters and six Kates (armed as horizontal bombers) to attack Guadalcanal in what was supposed to be a coordinated strike with Japanese land-based bombers (which had turned back due to bad weather). Saratoga’s radar detected Ryujo’s strike as it headed in-bound toward Guadalcanal. Three of Ryujo’s Zeros and four Kates were lost on the ineffective bombing mission to Guadalcanal, which was disrupted by Marine fighters at a cost of three Wildcats.

At 1345, Saratoga launched 30 SBD dive bombers and eight TBF torpedo bombers (with no fighter escort), again under the command of Felt, to attack the Ryujo. At 1410, two Enterprise TBF torpedo bombers on a search mission located and reported the Ryujo, but interference between fighter-direction and search frequencies prevented Enterprise from receiving the message; the two TBFs then conducted an unsuccessful air attack on Ryujo. Two more Enterprise TBFs found the Ryujo shortly after, and one was shot down by Ryujo fighters. Two more Enterprise SBDs located the Japanese Advance Force and conducted an unsuccessful attack on the Japanese heavy cruiser Maya.

Meanwhile, a bit after 1400, a floatplane from the Japanese heavy cruiser Chikuma sighted the U.S. carriers. Again, U.S. fighters shot the plane down before it could issue a contact report, but this time the Japanese immediately figured out that the loss of contact was a strong indication of the presence of U.S. carrier aircraft (and carriers), and, in short order, additional scout aircraft were en route toward the last known location of the downed plane. Unlike at Midway, Nagumo did not hesitate. At 1455, while Saratoga’s air group was headed toward Ryujo, 27 Val dive bombers and ten fighter escorts in an integrated strike from Shokaku and Zuikaku were launching to strike the U.S. carriers, while a second similar-sized strike package was being spotted on deck and armed to launch another strike an hour later. The Japanese battleships in the Advance Force, Hiei and Kirishima, increased speed to close on the American position. As the two strike groups were attacking or heading toward the U.S. carriers, nine B-17s bombed the Japanese carriers from high altitude around 1800, but, as at Midway, hit nothing, although they did shoot down a Zero.

Despite his best efforts, this time Fletcher was in an even worse situation than at Coral Sea. There, the Japanese main carrier force did not know where the U.S. carriers were when almost the entire U.S. strike capability was committed against a less important target (the Shoho). This time, the Japanese main carrier force had a good idea where the U.S. carriers were, whereas U.S. scouts had yet to locate the main Japanese carrier force or even spot any carrier aircraft (except those from Ryujo, which, like the Shoho, was a much less important target than the Shokaku and Zuikaku).

Shortly before 1500, two Enterprise SBD Dauntless dive bombers on a scouting mission sighted the Shokaku and Zuikaku, issued a contact report that failed to get through to the Enterprise, and immediately attacked the Japanese carriers. Flown by Lieutenant Ray Davis and Ensign R. C. Shaw, the two SBDs were detected by Shokaku’s radar, but in coordination problems of their own, the Japanese radar report failed to get to the bridge. However, Shokaku’s lookouts spotted the two dive bombers just in time for Shokaku to take evasive action, causing both bombs to barely miss, although they nevertheless killed six Shokaku crewmen. A post-strike report also failed to reach the Enterprise, but was intercepted by Saratoga, which was the first word Fletcher had that Japanese carriers were nearby. Once again, the U.S. strike was committed to a lesser target, but this time Japanese strikes were inbound.

After initially seeing nothing but empty ocean, the Saratoga strike group finally found the Ryujo and her escorts at 1536. Commander Felt divided his formation. At 1550, 18 SBD dive bombers and five TBF torpedo bombers went after Ryujo, while seven SBDs and two TBFs went after the heavy cruiser Tone. Captain Tadao Kato proved to be extremely competent at evasive maneuvers, causing the first ten dive bombers to miss. Felt then directed that all aircraft go after the Ryujo and dove on Ryujo himself, leading the way by personally planting a bomb on the ship (although Kato later claimed that none of the U.S. dive bombers scored a direct hit, near misses were numerous and damaging). The seven SBDs that had been initially directed to attack Tone pulled up in mid-dive and then attacked Ryujo, claiming several hits. The two TBF’s didn’t get the word and conducted an unsuccessful torpedo attack on Tone. The other five TBF’s of Torpedo Eight kept trying to set up an attack on the Ryujo, but spray from the near misses kept obscuring the target. After several attempts, the TBFs executed a near textbook “anvil” attack, with three attacking from the starboard bow and two from the port bow, so that no matter which way Ryujo turned, she could not evade the torpedoes. (Although the new TBF Avengers were greatly superior to the TBD Devastators that had been slaughtered at Midway, they still carried the unreliable Mark 13 torpedo). Of three torpedoes that possibly hit the Ryujo, one actually exploded, and the damage would ultimately prove fatal. Of the three Torpedo 8 aircraft that could have launched the lethal torpedo, one was piloted by Bert Earnest, who had been awarded two Navy Crosses at Midway as the only one of six Midway-deployed Torpedo Eight Detachment TBFs to have survived (barely) the first attack on the Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. Ryujo eventually succumbed to progressive flooding from the torpedo hit, but her loss could not be confirmed by naval intelligence until early 1943.

At 1602, Enterprise radar momentarily detected the first inbound Japanese strike at 88 miles. Both carriers began launching additional fighters until, by 1630, 53 Wildcats were in the air (all fighters had been held back for fleet defense). All 53 were on the same fighter-direction frequency. Another radar hit occurred at 1619 at 44 nautical miles, and Wildcats sighted the Japanese strike at 1629, which split into two groups. Radar at the time could only determine distance, not altitude. The Japanese came in at 16,000 feet. The Wildcats were all too low. Radio discipline immediately broke down, along with any hope of coherent radar fighter direction. Only about 10 Wildcats reached the Val dive bombers before they commenced their dives; a few more Wildcats followed the Vals down. The escorting Zeros were very effective at protecting the Japanese dive bombers.

Machinist Donald E. Runyon (an enlisted pilot in Fighter Squadron 6, on Enterprise) knocked down three Vals and a Zero, the high tally of the battle by any U.S. pilot. Machinist D. C. Barnes (also of VF-6) led a division of four Wildcats in a dive with the Val dive bombers, and Ensign R.A.M Dibb downed two, while one of the Wildcats was badly shot up by a good Val rear gunner. A number of other Vals were claimed shot down by other fighters; however, the combined claims of planes downed by fighters and shipboard anti-aircraft gunners significantly exceeded the number of Japanese planes involved.

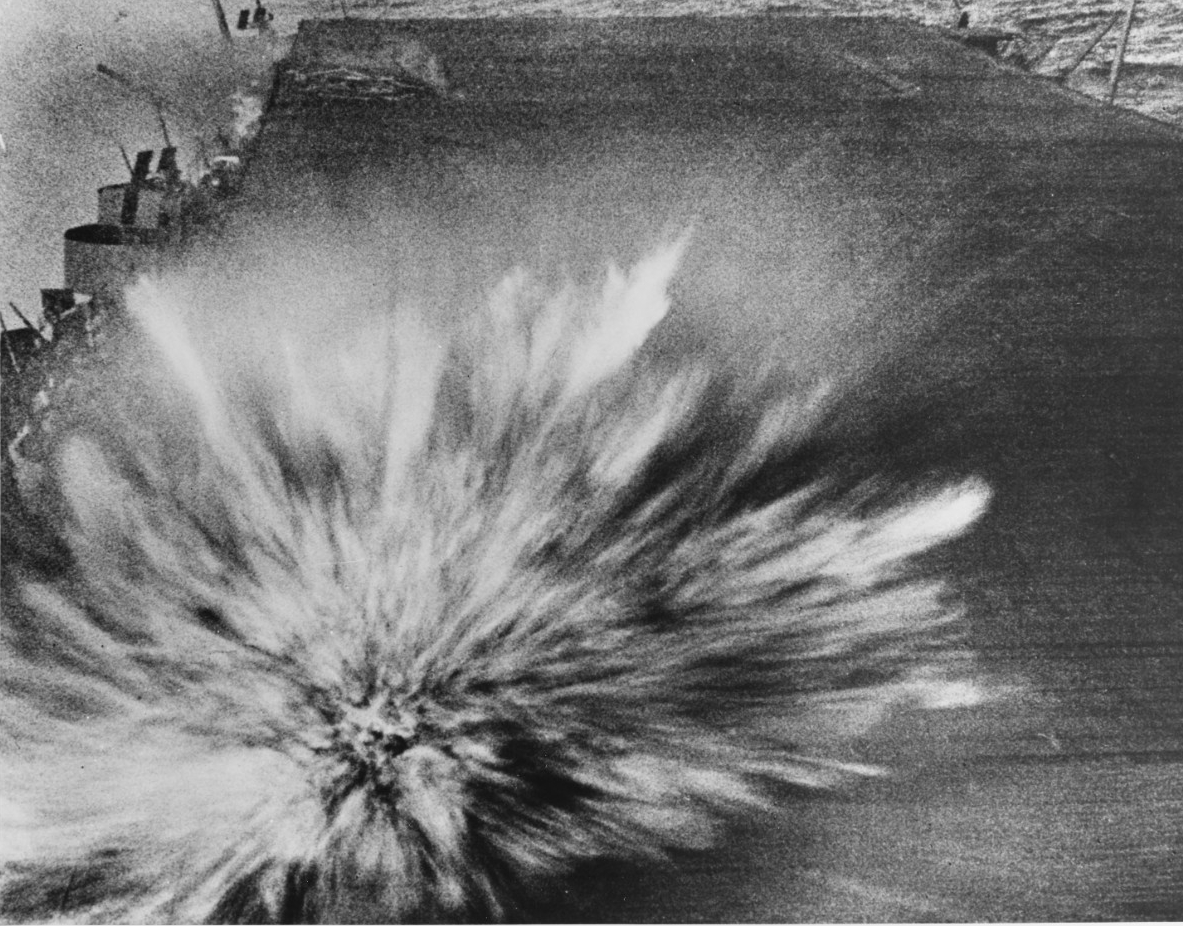

Although radar had provided early warning, cloud formations obscured the Japanese approach and the air battle raging above. The first time shipboard anti-aircraft gunners saw the Japanese was at 1642, when they were directly overhead commencing their dives. The Japanese plan was to attack Enterprise with 18 Vals and Saratoga with nine Vals. It is not known with certainty how many Vals made it through the U.S. fighters, but most of them did, inflated claims notwithstanding. The Vals that intended to go for Saratoga were badly mauled and, in the end, all the surviving Val dive bombers attacked the Enterprise. Enterprise anti-aircraft fire was now enhanced with significant numbers of new 20 mm Oerlikon guns and, as Japanese bombs fell, pieces and parts of the planes that dropped them fell too. The 20 mm couldn’t knock down planes before they released their ordnance, but they took a devastating toll of those that did. Several bombs (and their disintegrating planes) were near misses, but the Japanese pilots were determined. The first bomb hit Enterprise at 1644 on the corner of the number three (aft) elevator and penetrated several decks into a petty officer’s mess, killing 35 men. The second bomb hit the aft starboard 5-inch gun gallery, taking out the guns and killing almost all their crews; another 35 men were killed. At 1646, a third bomb hit just aft of the island, with a low-order detonation that resulted in one of the most famous photographs of the war, which caught the bomb at the instant of detonation, but which did not kill the photographer (or anyone else) as reported in many accounts. (A Navy photographer was killed, but by the second bomb in the gun gallery.)

About five Vals peeled off and attacked the new battleship North Carolina (BB-55), a big mistake. With 20 5-inch/38-caliber dual purpose guns, numerous quad 1.1-inch machine guns (still jam-prone), and dozens of new 20 mm guns, the North Carolina put up such an intense volume of fire that observers were convinced she was on fire, but she suffered only superficial damage from a near miss.

The first attack cost the Japanese 18 dive bombers (of 27) and six Zeros (including several planes that went down on the way back to their carriers) to obtain three hits, at a cost of eight defending Wildcats. Enterprise’s damage control was superb. Despite the high casualties, the holes in the flight deck were quickly patched and, one hour after the attack, Enterprise began recovering aircraft. Then, Enterprise lost her steering, with her rudder jammed over to starboard. One of her two electric rudder motors shorted out after water poured in when ventilation trunk was mistakenly opened remotely. The seven men in the compartment were overcome before they could switch to the alternate motor. As the second Japanese strike proceeded inbound, Enterprise was trapped steaming in a circle, unable to take any evasive action. Chief Machinist William A. Smith donned a self-contained breathing apparatus (which had been modified by another chief for extended endurance) and entered the compartment. Smith was twice overcome and had to be pulled out by other Sailors using a safety line. On his third attempt, at 1858, Smith succeeded in starting the alternate motor and Enterprise regained steering control. While Enterprise was circling and the second Japanese strike was 10 minutes out, in probably the luckiest U.S. break of the battle, the radio operator in the Japanese strike leader’s plane miscopied a position report on the U.S. carriers and the strike changed course. The second Japanese strike never did find the U.S. carriers.

When the first Japanese strike was inbound and the fighters had been launched, the two U.S. carriers launched everything that could fly just to get them off the deck, which included some aircraft that were armed and ready for a follow-on strike and others that weren’t. On Saratoga, pilots were in planes to move them around the deck when they were ordered to immediately launch, a number without their flight gear, and others without charts of any kind. The result of this was a number of uncoordinated groups of aircraft groping in increasing darkness trying to find any kind of Japanese targets. One group of Enterprise torpedo bombers commenced an attack only to discover the target was a reef. At 1735, a group of five Saratoga Torpedo 8 TBF Avengers (of which only squadron commander Lieutenant Harold H. “Swede” Larsen had his flight gear), which had joined up with two SBD dive bombers, located elements of the Japanese Advance Force battleships and cruisers. As at Midway, Torpedo 8 unhesitatingly pressed home their attack. Unlike Midway, none were shot down, although two damaged aircraft had to ditch; their crews were eventually recovered. But like Midway, none of VT-8’s torpedoes hit, or if they did, they didn’t work. The two dive bombers attacked what they reported as the Japanese battleship Mutsu. The target was actually the seaplane carrier Chitose. Neither bomb was a direct hit, but several seaplanes caught fire and the Chitose sprung some severe leaks and developed a dangerous list, but made it back to Truk. As darkness fell, some U.S. aircraft recovered on Guadalcanal, and some succeeded in making night landings on the carriers. Japanese battleships attempted to close on the U.S. position to conduct a night attack on any damaged U.S. ships (and typically, Japanese aviators had claimed a number). Three Japanese destroyers did bombard Guadalcanal during the night (and several Marine aircraft attacked them at night, unsuccessfully). However, by midnight, both Nagumo and Fletcher decided they had had enough and, by daybreak, the two carrier forces were far apart steaming in opposite directions. Their respective caution would anger both Yamamoto and King; Nagumo would be given yet another chance; Fletcher would not.

Actions on 25 August

As a result of confused Japanese command and control, Rear Admiral Tanaka was still trying to get his convoy to Guadalcanal while the Japanese carriers, with his air cover (after Ryujo had sunk), were steaming in the opposite direction. After three days of successfully outwitting all attempts to attack him, Tanaka was dogged through the night by a radar-equipped PBY, and his luck ran out just after 0800 on 25 August, when five Marine and three Navy SBD dive bombers from Guadalcanal commenced an attack. Tanaka’s flagship, the light cruiser Jintsu, was seriously damaged and Tanaka was initially knocked unconscious.The troop transport Kinryu Maru was hit and set on fire. One Marine pilot discovered that his bomb had not released and he turned back and conducted a solo attack on the Japanese force, with a near miss on another transport. The destroyer Mutsuki went alongside the stricken Kinryu Maru. Three US Army Air Force B-17 bombers arrived overhead at 1027. Given the B-17’s long track record of not hitting anything, Mutsuki’s skipper contemptuously refused to break away and maneuver. Although a skilled warship skipper could avoid bombs dropped by horizontal bombers, the ship had to actively take evasive action. As a result, Mutsuki took a direct hit and sank at 1140, taking 40 crewmen with her. Another Japanese destroyer sank the Kinryu Maru with a torpedo, and the rest of the convoy beat a hasty retreat, thus ending the battle.

The U.S. had achieved the strategic intent of stopping a Japanese reinforcement of Guadalcanal, although the 1,500 troops on the transports, by themselves, would not have made much difference, being greatly outnumbered by the Marines already on Guadalcanal. The Japanese also found alternate means to get troops ashore, with night-time runs aboard Japanese destroyers. The damaged Enterprise required repairs in Pearl Harbor, leaving only three operational U.S. carriers in the Pacific, which would quickly be whittled to one by Japanese submarines. U.S. shipboard anti-aircraft fire was greatly improved over the first battles of the war, but the U.S. was still struggling with how to make best use of radar in providing for fleet air defense.