H-047-1: The Last Battle of the Atlantic—Operation Teardrop

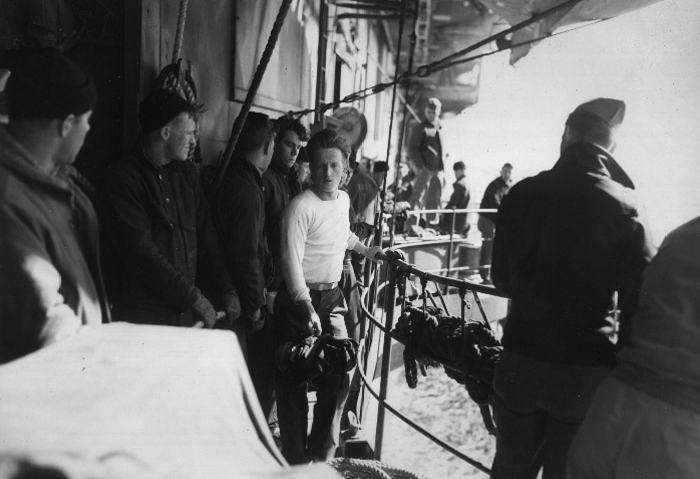

German Type IX submarine docking at Tromso, Norway, during the latter part of World War II. Note the boat's unofficial insignia and ice flows. The U-boats comprising Gruppe Seewolf in April 1945 were Type IXs based in occupied Norway. They were all fitted with snorkel arrays, which were retracted into a compartment under the upper deck plates to starboard rear of the sail when not in use (NH 41374).

Of note, given that so many German submarines were lost with all hands, determining exactly which U-boat sank which ships and which ships sank which U-boat still remains a work in progress. I use Samuel Eliot Morison’s work as a baseline, but update when there is more recent analysis that strongly indicates differently, especially since Morison didn’t have access to Ultra code-breaking intelligence that was critical to the Allied success in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Gruppe Seewolf and Operation Teardrop, April–May 1945

In early March 1945, decryption of German Enigma-coded radio transmissions indicated the Germans were commencing an offensive U-boat operation against the U.S. East Coast. Beginning about 14 March, a total of nine German Type IX U-boats (all equipped or retrofitted with snorkels) left their bases in German-occupied Norway en route the East Coast of the United States and Canada. Six U-boats were designated Gruppe Seewolf (U-518, U-546, U-805, U-858, U-880, and U-1235) and were ordered to the U.S. East Coast, while U-530 and U-548 (which departed in early March) were initially ordered to operate off Canada. The ninth U-boat, U-881, departed later from Norway, on 9 April, and was ordered to join the group.

This German deployment had been anticipated and was of grave concern to senior U.S. Navy commanders due to the possibility that these U-boats might be equipped to launch V-1 pulse jet–powered pilotless flying bombs (“buzz bombs”) or something similar, to be used against U.S. East Coast cities. Rumors of this supposed capability began circulating in the late fall of 1944, some of which were disinformation spread by captured German spies. In September 1944, a German spy was captured after the U-boat that was transporting him to the United States was sunk. This spy, Oscar Mantel, claimed the Germans were preparing such attacks. (In November 1944, the Germans began development of a canister that could be towed behind a submarine and used to launch a V-2 guided ballistic rocket, but no prototype had even been started before the war ended—the technical challenges of transporting and launching a liquid-fueled rocket in this manner were pretty daunting.)

In December 1944, German spies William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel, who had been landed in Maine by U-1230 and then captured, further told U.S. interrogators that a group of rocket-equipped submarines were being readied for use. Relying on photographic and other intelligence, both the U.S. Tenth Fleet and the British Admiralty discounted these reports. Nevertheless, in January 1945, German Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer claimed in a propaganda broadcast that V-1s and V-2s would hit New York by the beginning of February.

On 8 January 1945, believing that the U.S. population on the U.S. East Coast was getting lax in abiding by wartime restrictions (such as blackouts), the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Jonas Ingram, held a press conference and stated that rocket attacks on the U.S. East Coast from submarines were possible. Needless to say, this caused a “sensation” in the press, and borderline panic amongst politicians. However, before Ingram’s announcement, the U.S. Navy had already put together a response plan, code-named Operation Teardrop, to counter the German rocket submarine threat (U.S. Army coastal defense and air forces would deal with the “robot rockets” once they were in the air).

There were already several German U-boats operating off the U.S. East Coast before Operation Teardrop began, mostly with little to show for their efforts. At this point in the war, the focus of German U-boat activities, now that most U-boats had been retrofitted with snorkels (which significantly improved their survivability), was in the approaches close to Great Britain. The use of the snorkel had made it significantly more difficult for Allied aircraft to find and kill U-boats, forcing a renewed reliance on painstaking searches by surface ships. A few U-boats were sent across the Atlantic to divert Allied resources away from the main effort. However, in March 1945, the U-boats operating near the United Kingdom were suffering very high losses (despite the snorkel) and the ones in the Western Atlantic weren’t faring much better.

U-Boat Losses off Eastern North America, March–April 1945

On 16 March 1944, U-866 (on her first patrol) barely survived a hedgehog attack by destroyer escort Lowe (DE-325) near Sable Island (about 175 nautical miles east-southeast of Nova Scotia). U-866 attempted to ride out further attacks sitting on the bottom, but repeated attacks by destroyer escorts Lowe, Pride (DE-323), Mosely (DE-321), and Menges (DE-320) destroyed her. U-866 sank no ships in her short life.

U-857 and U-879 had entered the Gulf of Maine in late March. On 5 April 1945, one of them torpedoed and damaged the tanker Atlantic States, which was towed into port. Within a few hours, two U.S. destroyer escorts and two frigates prosecuted the submarine. Destroyer escort Gustafson (DE-182) was given credit at the time for sinking U-857 early on 7 April 1945 as she was attempting to hide on the bottom. Additional analysis in 1994, however, indicated that this kill was “non-sub.”

According to Morison, U-879 was sunk by destroyer escort Buckley (DE-51), assisted by Reuben James (DE-153), on 19 April 1945 off Sable Island. Subsequent analysis indicated this may actually have been U-548, but was definitely a kill. U-548 was lost with all hands on her fourth patrol.

The only German submarine to have much success at all in April 1945 was either U-548 or, more likely, U-857. On 14 April, a German submarine torpedoed and sank the unescorted freighter Belgian Airman off Cape Henry, Virginia. This provoked a major hunt by six destroyer escorts from Hampton Roads, plus a mix of destroyers and gunboats from Rhode Island, Mariner flying boats and Ventura aircraft from Norfolk and Elizabeth City, and several blimps, all of which came up empty, mostly due to fog. On 18 April, the unescorted tanker Swiftscout was torpedoed and sunk off the Delaware Capes by the elusive submarine. On 23 April, the Norwegian tanker Katy was hit by a torpedo off Cape Henry, but her crew was able to bring her in to Lynnhaven Bay, Virginia.

On the night of 29–30 April, U-857 (or U-548 or U-879) was attempting to attack convoy KN-382, when she was sighted and driven off by the frigate Natchez (PF-2). The submarine was then pursued by destroyer escorts Bostwick (DE-103), Coffman (DE-191), and Thomas (DE-102). At 0115 on 30 April, Bostwick delivered a depth-charge barrage that forced the submarine down to 600 feet. Despite the submarine’s evasive maneuvers, a little over three hours later, Coffman and Thomas delivered a creeping hedgehog attack that sank the submarine with all hands. (According to Morison, this was U-548. More recent analysis indicated this was U-879. U-857 was most likely responsible for sinking the ships off Cape Henry, but her fate remains unknown.)

The Barrier Forces

The U.S. response to Gruppe Seewolf was a far cry from the first hunter-killer missions in 1943, when an escort carrier would deploy with four or five escorts, some of which were World War I–vintage “four-piper” destroyers. Operation Teardrop included two “barrier forces,” each with two escort carriers and over twenty destroyer escorts. U.S. intelligence analysis and operational analysts at Tenth Fleet were able to track the progress of Gruppe Seewolf across the Atlantic, which was slow, since the submarines were transiting under snorkel. The challenge was how to defend the entire U.S. eastern seaboard against such a group of submarines. Fortunately, the Germans persisted in stubbornly believing that their codes were not being broken and read by the Americans and the British—by this time of the war almost as fast as the Germans transmitted their traffic.

The First Barrier Force included 20 destroyer escorts divided between a Northern Force, led by escort carrier Mission Bay (CVE-59), commanded by Captain John R. Ruhsenberger, and a Southern Force, led by escort carrier Croatan (CVE-25), commanded by Captain Kenneth Craig. With good intelligence on the U-boats’ track, most of the destroyer escorts set up a 120 nautical mile–long barrier in the mid-Atlantic south of Iceland at 30 degrees west, with the two escort carriers and four escorts each operating about 40–50 nautical miles behind. The weather conditions were atrocious, with frequent heavy fog and seas that were described at time as “mountainous.” (Over 100 Sailors on Croatan were injured when a heavy roll sent the entire mess deck flying during a meal.) These conditions severely hampered both carrier and shore-based air operations, which still had not developed tactics to effectively deal with the “snorkel problem.”

Although there was intelligence reporting on Gruppe Seawolf’s progress across the Atlantic, there were no good high-frequency direction finding (HF/DF) fixes or sightings until 15 April. Finally, at 2135 that day, the destroyer escort Stanton (DE-247), in Croatan’s screen, detected a radar contact at 3,500 yards in the heavy fog. Stanton closed to 1,000 yards before illuminating the contact with a searchlight, which proved to be U-1235 running on the surface because the seas were too heavy for snorkel use. The submarine immediately dove as Stanton moved in for a hedgehog attack. Assisted by Frost (DE-144), Stanton made three hedgehog attacks and, at 0333, on 16 April, hit the submarine, causing several explosions that culminated in an unusually large underwater explosion. U-1235 was lost with all hands on her second patrol, without sinking any ships.

Forty minutes later and only 1.5 nautical miles from U-1235’s last datum, Frost detected another surface contact on radar, initially thinking that somehow U-1235 had survived. This was actually U-880, which had closed on the destroyer escorts as they were prosecuting U-1235, then apparently thought better of it and was attempting to depart the area running on the surface in the thick fog. Frost fired a star shell that failed to illuminate the target. Finally, when the range was down to 500 yards, Frost used her searchlight to reveal the submarine. However, the seas were too heavy to change course to ram or even to bring the 3-inch main battery guns to bear, and the submarine submerged after being hit in the conning tower by smaller-caliber rounds. Frost gained sonar contact and was assisted by Stanton and Huse (DE-145) in tracking the submarine. At 0406, Stanton fired a hedgehog barrage that resulted in yet another massive explosion, jolting even Croatan 15 nautical miles away and causing crewmen on Stanton to think they’d been hit by a torpedo. Frost conducted another hedgehog attack just to be sure, but U-880 had been lost with all hands on her first patrol, having sunk no ships.

The unusually strong underwater explosions that resulted from the hedgehog attacks on U-1235 and U-880 only raised further concern with Admiral Ingram and Tenth Fleet that the submarines had some kind of special weapons on board. At this point, based on intelligence and HF/DF, Ingram ordered the First Barrier Force shifted to the southwest to conform to the U-boats’ expected track. On the night of 18–19 April, a U.S. Navy PB4Y-1 (B-24) Liberator of VPB-114 flying from Terceira, Azores, sighted U-805 on the surface using the plane’s Leigh light (a big carbon-arc searchlight) about 50 nautical miles from Mission Bay, but did not attack because the submarine submerged before it could be confirmed as enemy. Spooked by so much U.S. radio traffic in the area, U-805 changed course to the north to try to go around.

On the night 20 April, U-546 unsuccessfully attempted to torpedo an unidentified U.S. destroyer escort. No U.S. ships reported being attacked.

On the night of 21 April, aircraft from Croatan and her escorts continued to try to locate U-805. She was finally detected by Mosely (DE-321) sonar and was depth-charged by Mosely, Lowe (DE-325), and J. R. Y. Blakely (DE-140), but escaped yet again. Mosely and Lowe had previously teemed up to sink U-866 near Sable Island on 18 March 1945.

Also on the night of 21 April, just before midnight, destroyer escort Carter (DE-112) detected U-518 on sonar in “mountainous” seas. Carter coached Neal A. Scott (DE-769) for a creeping hedgehog attack on the submarine, which had gone stationary, but missed. Carter then moved in for her own attack and, at 2309, delivered a fatal hedgehog attack. U-518 was lost with all hands on her tenth patrol, having sunk nine merchant ships and damaged three others, although none on this patrol.

Second Barrier Force

On 21 April 1945, the First Barrier Force was relieved by the Second Barrier Force. The Second Barrier Force consisted of the escort carrier Bogue (CVE-9), commanded by Captain George J. Dufek, and ten destroyer escorts, plus escort carrier Core (CVE-13), commanded by Captain R. S. Purvis, and twelve destroyer escorts. The Second Barrier Force used somewhat different tactics. The destroyer escorts formed a line at five–nautical mile intervals for 120 nautical miles, with Core anchoring the northern end of the line and Bogue the southern end. Starting at 45 degrees west, the whole line began sweeping east until reaching 41 degrees west.

On 23 April, Grossadmiral Doenitz sent an order dissolving Gruppe Seewolf and directing the U-boats to proceed for independent operations along the U.S. East Coast. Doenitz did not know that three of the original six Gruppe Seewolf submarines had already been sunk.

On 23 April, destroyer escort Pillsbury developed a contact near the center of the Second Barrier Force line. A TDM Avenger off Core attacked a contact and killed a large whale, which was found by the destroyer escorts. However, at 1347 the skipper of VC-9 on the Bogue, Lieutenant Commander William South, sighted a submarine breaking the surface 74 nautical miles from Bogue near the center of the line. An attack by South was unsuccessful, as were those by another flight of Avengers. U-546 survived to fight and kill one more day.

Loss of Eagle Boat 56 (PE-56), 23 April 1945

On 23 April, as Operation Teardrop had been sinking three of the seven submarines in Gruppe Seewolf, another German U-boat, which had departed Norway on 23 February and had been operating in the Gulf of Maine with no luck since early April, finally sank a ship. Under the command of 24-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Helmut Fromsdorf, U-853 was on her third patrol and had yet to sink a single ship, although on her second patrol under her previous commanding officer she had so many close escapes that she was nicknamed “Moby Dick” or the “White Whale” by U.S. Sailors.

U-853’s target on 23 April was the Eagle-class patrol boat PE-56, one of a class of 60 submarine chasers built during World War I, of which only eight were still in service by World War II. PE-56 was assigned to Naval Air Station Brunswick, Maine, and was towing targets for practice by dive-bombers three nautical miles off Cape Elizabeth, when she suffered a massive explosion amidships.

Only 13 of PC-56’s crew of 67 survived the sinking. The survivors reported that they were hit by a torpedo, and five of them stated they had seen a submarine with a gold and red emblem on the conning tower. (Although not known at the time, the emblem of U-853 was a red horse on a gold shield. Such painted emblems were not authorized, but some U-boats had them anyway.) Shortly after the sinking, destroyer Selfridge (DD-357) gained solid sonar contact on a submarine and dropped nine depth charges without effect. Frigate Muskegon (PF-24) gained sonar contact on a submarine, but was also unsuccessful in sinking it. Despite the witness reports and subsequent attacks on a submarine, the Navy’s court of inquiry determined that the cause of the sinking was a boiler explosion, a conclusion that remained unchallenged until the late 1990s.

In response to requests by outside researchers who had concluded U-853 was responsible for the sinking of PC-56, the Naval Historical Center (predecessor of NHHC) reviewed all available documentation and concluded that U-853 was responsible and that PC-56 was a combat loss. In 2001, Chief of Naval Operations Vernon Clark and Secretary of the Navy Gordon England concurred. This is the only time the U.S. Navy has overturned a court of inquiry. Purple Heart medals were awarded to the three living survivors and the next of kin of others on PC-56. This also made the boat the second-to-last U.S. Navy vessel sunk in the Atlantic Theater in World War II. In 2019, a civilian dive expedition finally found the wreck of PC-56 with the boilers intact.

Loss of Frederick C. Davis (DE-136), 24 April 1945

U-546 was a Type IXC/40 U-boat on her fourth patrol with no sinkings to her credit. Under the command of Kapitänleutnant Paul Just, U-546 sighted the escort carrier Core on 24 April. While maneuvering to attack and attempting to slip through Core’s screen, the boat was detected at close range by destroyer escort Frederick C. Davis (DE-136) at 0830. Frederick C. Davis was an Edsall-class destroyer escort, armed with three single 3-inch/50-caliber guns, one twin 40-mm, eight single 20-mm, one triple 21-inch torpedo mount, a hedgehog projector, eight side-throwing depth-charge projectors, and two depth-charge rolling racks on the stern. Frederick C. Davis had been awarded a Navy Unit Commendation for her role in the landings at Anzio, Italy, in 1944, where, for six months, she provided anti-aircraft and naval gunfire support, and was equipped with gear to jam German radio-controlled rocket-assisted glide bombs. She was credited with shooting down 13 German aircraft. Now under the command of Lieutenant Commander James R. Crosby, USNR (some accounts note his rank as lieutenant), the “Fightin’ Freddy” had a reputation as a taut and alert ship.

Frederick C. Davis detected the submarine by sonar at 2,000 yards ahead. For whatever reason, general quarters was not sounded, but the guns and hedgehog projectors were manned and ready. As the submerged submarine passed down the starboard side, the officer of the deck ordered a hard right turn, but contact was lost in the noise of Frederick C. Davis’ own Foxer acoustic torpedo countermeasure system. U-546 had launched a T-5 acoustic homing torpedo from her stern tube at range of 650 yards, which, despite the Foxer, hit Frederick C. Davis on the port side in the forward engineering spaces. The blast was devastating, killing the commanding officer, the officer of the deck, and almost everyone on the bridge and many in the forward part of the ship. In only a few seconds, the engineering spaces and several large crew-berthing compartments were flooded and fires turned the bridge area into an inferno. Only one officer in the combat information center survived. The wardroom deck was blown upward, killing all the officers who were still at breakfast along with the steward’s mates. Nine minutes after the hit, the ship broke in two and, six minutes later, the bow went under.

Survivors in the aft end of the ship, led by Ensign Philip K. Lundberg, the assistant damage control officer, desperately tried to establish watertight integrity in the hopes the stern would remain afloat, but to no avail. Before the ship went under, crewmen were able to safe all but two of the depth charges, which exploded when the stern went under, killing many of those in the cold water. Of Frederick C. Davis’ crew of 192, 126 perished, including her skipper and nine other officers.

(Ensign Lundberg was the junior of three surviving officers. He would go on the earn a PhD in History at Harvard University under Professor Samuel Eliot Morison, and his thesis would be the basis for The Atlantic Battle Won, the tenth volume of Morison’s History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. He would become one of the most famous and prolific naval historians, would be Curator Emeritus of the Smithsonian Museum of American History, and would be awarded the Commodore Dudley W. Knox Naval History Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013. He passed away in 2019.)

Hunt for U-546

The screen commander, Commander R F.S. Hall, saw the explosion of Frederick C. Davis and immediately ordered destroyer escorts Hayter (DE-212) and Neunzer (DE-150) to prosecute the submarine, and Flaherty (DE-135) to rescue survivors. As Flaherty approached the sinking Frederick C. Davis, she detected the submarine in close proximity, using the wreckage as cover. Flaherty prosecuted the U-boat and Hayter was diverted to the rescue, aided by aircraft off Core sighting survivors in the oil slicks. The Foxer countermeasure on Pillsbury (with the screen commander embarked) may have disrupted Flaherty’s first attempt at a creeping hedgehog attack. However, Pillsbury regained contact and directed Flaherty to a hedgehog attack at 0951 that missed. Flaherty then mistook the submarine’s Pillenwerfer sonar decoy as a torpedo launch and the warning call caused Hayter to temporarily break off rescue efforts. (A Pillenwerfer was a canister filled with calcium hydride, which, when mixed with seawater, created a hydrogen bubble cloud.) Nevertheless, at 1025, Flaherty made another hedgehog attack that was also unsuccessful. U-546 almost made a getaway at this point, but, at 1156, Flaherty picked her up again.

By this time, nine destroyer escorts were searching for U-546. Varian (DE-798), Janssen (DE-396), Hubbard (DE-211), Neunzer, and Flaherty all made multiple attacks. Although unsuccessful, these kept U-546 under, exhausting her crew and batteries. Heavy fog kept aircraft from Core from being of much help. At 1513, Varian detected U-546 at a depth of 600 feet. Chatelain (DE-149) also gained contact and guided Varian and Neunzer for another hedgehog attack at 1556, also unsuccessful. Contact was lost again until Varian detected the submarine and guided Keith (DE-241) on a depth-measuring run that determined the submarine had come up to 160 feet.

Other than the repeated hedgehog attacks, U-546 had no idea where the U.S. ships were because she had been damaged in an early attack and had to use her main pumps to control flooding, which blanked out her hydrophone. Finally, at 1810, a hedgehog from Flaherty blew a 15-inch hole in U-546’s pressure hull, smashed the bridge, and ruptured batteries, causing chlorine gas to leak. Even so, it took another hedgehog attack before the U-boat’s skipper decided he had no choice but to come to the surface and fight it out. At 1838, U-546 broke the surface and promptly fired a torpedo at Flaherty, which missed. Flaherty returned fire with two torpedoes that also missed. It was U-546’s last gasp as Pillsbury, Keith, Neunzer, and Varian all blasted away at the submarine with gunfire. At 1845, Commander Hall ordered a cease-fire as U-546 obviously up-ended and sank.

Somewhat surprisingly given the volume of fire directed at U-546’s conning tower, Kapitänleutnant Just and 32 crewmen were rescued by the U.S. ships after surviving the sinking. Morison described the survivors as “a bitter and truculent group of Nazis, who refused to talk until after they had been landed at Argentia and had enjoyed a little ‘hospitality’ in the Marine Corps brig.” The surviving Germans received appropriate and even considerate treatment while aboard U.S. ships, but Morison’s description euphemizes what actually happened afterward.

Upon arrival at the U.S. base in Argentia, Newfoundland, on 27 April, the U-546 commander, first officer, and six other crewmen, considered “specialists,” were separated out. They were then subjected to solitary confinement and repeated exhausting exercise, and, when unable to continue, were repeatedly beaten with rubber truncheons. Lieutenant Commander Leonard A. Myhre, skipper of Varian, which had delivered the Germans to Argentia, was witness to one of the beatings of Just, and lodged a strong protest.

On 28 April, two interrogators from Washington arrived—one dressed as a Navy captain, but apparently a civilian agent—presumably from the joint Army-Navy interrogation center at Fort Hunt, south of Alexandria, Virginia. The interrogators reported to Tenth Fleet that the Germans were extremely security conscious, and would not even give up information that was already known to U.S. intelligence via Enigma decrypts. Later ,on 30 April, the German commanding officer was subject to what Tenth Fleet records described as “shock interrogation,” the exact nature of which is unknown to this day, but it resulted in Just ending up unconscious and waking some time later. The Germans were then taken to the interrogation facility at Fort Hunt, where they were subject to still more beatings. The records from Fort Hunt were burned en masse after the war.

Frederick C. Davis survivor and naval historian Philip K. Lundberg described the treatment of U-546’s crew as “a singular atrocity” motivated by the interrogators need to get information quickly. This may be about as close to an actual “ticking bomb” scenario often hypothesized as an excuse to justify torture in that there was great concern that the Gruppe Seewolf submarines were going to attack U.S. cities with missiles. However, since none of submarines were equipped with missiles or rockets of any kind, the German crewmen could provide no information about them no matter how many times they were beaten. Finally, it became apparent that there was no missile threat from German submarines (although the Germans had conducted a small number of unsuccessful experiments in 1942, during which U-511 test-fired a variety of rockets, of which the crew of U-546 knew nothing.) Of note, after the war, a U.S. variant of the V-1 (the JB-2 Loon) was test-fired from submarines Cusk (SS-348) and Carbonero (SS-337) in a successful series of tests between 1947 and 1951, demonstrating that it would have been technically possible for the Germans to do the same.

Barrier Force Operations Continued

With two of the original Gruppe Seewolf submarines not accounted for (U-805 and U-858) and getting closer to the U.S. eastern seaboard, Mission Bay was ordered back to sea to augment the Second Barrier Force. By 2 May, the force included three escort carriers and 31 destroyer escorts, but only one additional contact and no successful attacks had been made after Gruppe Seewolf was ordered to split up on 23 April.

Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz as German Head of State, 30 April 1945

On 30 April, as the Soviet Red Army was advancing through the bombed-out rubble of Berlin, Adolf Hitler, “der Führer” of the 1,000-year German Reich, committed suicide. In his last will and testament he named the commander-in-chief of the German navy (the Kriegsmarine), Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, as head of state, minister of war, and supreme commander of the German armed forces. This came as a surprise to Doenitz and just about everyone else. However, Hitler suspected that more obvious successors, such as Hermann Goering of the Luftwaffe and Heinrich Himmler of the SS, were attempting to cut their own deals with the Allies; one of Hitler’s last acts was to denounce both of them as traitors. Hitler also distrusted the army following the failed 20 July 1944 assassination attempt. Although attempts were made after the war to “soften” his image, Doenitz earned Hitler’s trust because he was a hard-core Nazi and anti-Semite.

Doenitz had commanded the Kriegsmarine since replacing Grossadmiral Eric Raeder on 30 January 1943. Raeder had fallen out of favor with Hitler due to the lack of success by the hugely expensive German surface navy. Doenitz had been the commander of the German submarine force since 1935 (when Germany had three submarines). He had served on U-boats during World War I and was captured by the British in October 1918 after his submarine, UB-68, suffered technical problems and had to be scuttled. By early 1943, however, the German submarine force was still on a roll and the Battle of the Atlantic was looking pretty bleak for the Allies (the turn wouldn’t come until May 1943—see H-Gram 019). Hitler looked on Doenitz’ actions with great favor.

Doenitz may have been a Nazi, but he was also a realist, and there was no question in his mind that Germany was going to lose the war and soon. Doenitz was quoted as saying, “I will hear no more of this heroes’ death business. It is now my responsibility to finish this.” By noon on 4 May 1944, Doenitz’ first surrender proposal was in the hands of British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of Allied Forces in The Netherlands and Northern Germany. However, it was conditional. Doenitz was trying to arrange for the Germans to surrender to the British and the Americans, but not to the Russians. However, the agreed and stated war aim of the Allies was “unconditional surrender” and General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, insisted on complete surrender before agreeing to cease hostilities.

Operation Hannibal, January–May 1945

As a gesture of good faith while Doenitz was still trying to negotiate, he sent an order on the evening of 4 May for all German ships and submarines at sea to cease hostilities effective 0800 on the following day. An exception were those German navy forces involved in Operation Hannibal, the evacuation by sea of hundreds of thousands of German soldiers and civilians trapped in East Prussia by the advancing Red Army. Montgomery took no action to stop this evacuation, which continued until the official surrender on 8 May.

Operation Hannibal was the largest naval evacuation in history, taking about 350,000 German soldiers and nearly 900,000 civilians out of East Prussia between 23 January and 8 May, at a horrific cost of over 20,000 people, mostly civilians. On 30 January, the Soviet submarine S-13 torpedoed and sank the German armed transport Wilhelm Gustloff, which was carrying soldiers, political and security functionaries, and many civilians, killing 9,343 mostly civilians, including about 5,000 children. On 10 February 1945, S-13 sank another armed transport, General von Steuben, with an estimated loss of 4,000 mostly civilians, and with only 300 survivors. On 16 April, Soviet submarine L-3 added to the grim tally, sinking the overloaded armed transport Goya, with an estimated loss of 6,600 mostly civilian lives. Only 183 survived, 176 of them soldiers. Wilhelm Gustloff and Goya are the two highest death tolls of single ships lost at sea in history. All told, some 158 German merchant ships and vessels went down under Soviet air and submarine attack during this period.

The Battle of Judith Point, 5–6 May 1945

Two German submarines operating off the U.S. East Coast, U-853 and U-88, either ignored the order to cease hostilities on 5 May or, more likely, didn’t get the order. U-853, which had sunk PC-56 on 23 April, had moved to a new operating area at the entrance to Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. At 1740 on 5 May, the submarine torpedoed the U.S.-flag collier Black Point. The torpedo blew off the collier’s stern and she quickly went down with the loss of 12 men, including one of the five Naval Armed Guard aboard, Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Lonnie Whitson Lloyd, who would be the last U.S. Sailor killed in the Battle of the Atlantic. Thirty-five men were rescued, including five Naval Armed Guard. Black Point would be the last U.S.-flag ship lost in the Battle of the Atlantic.

A passing Yugoslav freighter, SS Kamen, rescued survivors from Black Point, sighted U-853, and radioed her position. A hunter-killer group was quickly organized under the command of Commander Francis C. B. McCune in destroyer Ericsson (DD-440), which was almost through the Cape Cod Canal en route Boston. Other ships of the group were already operating nearby, so while Ericsson was transiting back through the canal, the destroyer escorts Atherton (DE-169) and Amick (DE-168), along with the Coast Guard–manned frigate Moberly (PF-63), quickly arrived in the area and, by 1920, commenced search for the submarine. Lieutenant Commander L. B. Tollaksen, USCG, on Moberly was senior officer present and took charge. Ultimately, a total of 11 U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ships arrived to block off the area.

Within 15 minutes of arriving, Atherton (Lieutenant Commander Lewis Iselin, commanding) gained sonar contact five nautical miles east of Block Island and, at 2028, delivered a full pattern of nine magnetic depth charges, one of which exploded, followed by two hedgehog attacks. Given the shallow depths (103 feet), it was unknown if hedgehog explosions were hits on the submarine or on the bottom. In fact, U-853 was trying to ride out the attacks while creeping along very close to the bottom. By this time, Ericsson had arrived and McCune assumed tactical command, ordering star-shell illumination that revealed oil and debris, but nothing positively confirmed from a submarine.

At 2337, Atherton regained sonar contact and delivered another hedgehog attack, which probably doomed the sub. McCune ordered Moberly to move in, discovering that the sub was still slowly moving, and directed another attack. At 0200, Moberly conducted another full hedgehog attack, and U-853 stopped moving and was on the bottom. The ships continued to search throughout the night and, although lifejackets, escape lungs and oil were observed at first light, attacks resumed, dropping more than 100 depth charges. At 0600, the ships were joined by two blimps from NAS Lakehurst, K-16 and K-58, which fired rocket bombs and then dropped a sonobuoy that detected a rhythmic hammering noise. The crew of U-853 was probably long dead by this point, but by noon on 6 May, debris had surfaced including U-853 skipper’s hat and chart table. At 1230, a diver from submarine rescue ship Penguin (ASR-12) went down and reported that the submarine’s pressure hull and interior were split open, with bodies visible inside. An attempt to reach the captain’s safe was unsuccessful. This convinced Commander McCune to terminate the action. “Moby Dick” and all 54 of her crew were dead.

U-853 is still on the bottom off Block Island in 127 feet of water. The hull has one hole near the radio room forward of the conning tower and another in the engine room on the starboard side. In 1960, a recreational diver brought up a body from the wreck. Although the body was buried in Newport with full military honors, the incident provoked former U.S. Navy admirals and some clergymen to petition the U.S. government for better protection of war graves. Two recreational divers have died over the years while exploring the wreck. The submarine’s two propellers are at the Naval War College Museum in Newport.

U-881 Sinking, 6 May 1945

U-881 was a late addition to Gruppe Seewolf, departing Norway on 8 April for her first patrol. Despite the addition of Mission Bay and her escort destroyers to the Second Barrier Force, two of the first six Gruppe Seewolf boats were unaccounted for, aswas the seventh submarine, U-881. Although the German surrender was anticipated at any moment, there was still great concern that one of the Gruppe Seewolf submarines could launch a missile attack against a U.S. East Coast city. Apparently, U-881 didn’t receive the order to cease hostilities on 5 May.

In the early morning of 6 May, U-881 was maneuvering to attack the escort carrier Mission Bay when she was detected at 0413 at close range by destroyer escort Farquhar’s (DE-139) sonar. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander D. E. Walter, Farquhar made a quick attack with 13 depth charges set on shallow. Contact ceased and it wasn’t until after the war that analysis confirmed U-881 went down with all 54 hands. This is why some accounts say U-853 was the last U-boat sunk by U.S. forces. However, the last was actually U-881.

The Surrender

At 0241 on 7 May 1945, at the direction of Doenitz, German Generaloberst Alfred Jodl signed the act of military surrender, surrendering all German forces without condition and taking effect the next day, which Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower accepted. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin insisted on a separate ceremony, during which the instrument of surrender was signed in Berlin the next day by German General-Feldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel.

On 8 May 1945, British Admiral Harold R. Burrough, acting for the Supreme Allied Commander Europe, gave orders for all U-boats at sea (there were 49) to immediately surface and fly a black flag or pennant to show compliance with the German surrender. The first submarine to comply was U-249, which was sighted surfacing off the Scilly Islands at the western entrance to the English Channel by a Navy Liberator of Fleet Air Wing 7 piloted by Lieutenant Frederick L. Schaum, USNR. Ultimately, the Germans would surrender 181 U-boats; 217 were scuttled by their own crews (this is Morison’s number—there is significant variance in other accounts). Most of the 118 newly completed next-generation Type XXI and XXIII U-boats were scuttled (only five Type XXIs and one Type XXIII were combat-ready at the end of the war).

On 9 May 1945, U-805, one of the two survivors of Gruppe Seewolf, broadcast her position as ordered southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. Destroyer escort Varian (DE-798) rendezvoused with U-805 on 12 May and put a boarding party aboard to take her to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where she arrived on 15 April. U-805 was used for several “Victory Visits” before she was sunk by the U.S. Navy in February 1946.

On 10 May, U-858, the other surviving Gruppe Seewolf boat, surrendered to destroyer escorts Pillsbury and Pope (DE-130), which put a boarding party aboard her and escorted her to the Delaware Capes on 14 May. Although U-805 made the first surrender radio call, U-858 was the first one boarded and is referred to as the first German submarine to surrender to the United States at the end of the war. U-858 was used in War Bond drives before being used for torpedo target practice and then scuttled in 1947.

Of note, it was Pillsbury’s boarding team that went aboard and captured the German submarine U-505 near the Canary Islands on 4 June 1944 while operating as part of the USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) hunter-killer group. The leader of the boarding team that went aboard U-505 and kept her from sinking was Lieutenant Albert David, who was awarded a Medal of Honor (to go with two previous Navy Crosses), who regrettably died of a heart attack at age 43 before President Truman could present the nation’s highest military award. U-505 is the only U-boat of those captured by or surrendered to the United States that still survives, and is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago (and well worth a trip to see).

U-873 was not part of Gruppe Seewolf, but departed Norway on 30 March on her first patrol and was heading for the Caribbean. The submarine was a Type IXD2, a long-range version of the more plentiful Type IXC/40. On 11 May, U-873 surrendered to destroyer escort Vance (DE-387), which put a “prize crew” on board and escorted the sub to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. U-873 was put in a dry dock and extensively studied, before undergoing tests and, later, being scrapped in 1948. After interrogation at Portsmouth, the handcuffed crew of U-873 was marched through Boston and pelted with garbage and insults, and, in violation of the Geneva Convention their personal possessions on the submarine were looted (this was also true of the other U-boats brought into Portsmouth). The commanding officer of U-873, Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Steinhoff (who had also been commanding officer of U-511 during the 1942 rocket-firing tests), showed signs of being roughly interrogated and then committed suicide on 19 May in his Boston jail cell while awaiting transfer to a prisoner-of-war camp in Mississippi.

U-1228 departed Norway on 1 April for operations in the Western Atlantic. Upon the surrender, U-1228 headed for the closest U.S. port, surrendered to destroyer escort Neal A. Scott (DE-769), and arrived at Portsmouth on 17 May. After being studied and tested, she was torpedoed and sunk as a target by submarine Sirago (SS-485) on 5 February 1946.

On 14 May, U-234 was intercepted by destroyer escort Sutton (DE-771) in the vicinity of the Grand Banks after U-234’s skipper had falsely radioed on 12 May that he was heading for Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was actually heading for Newport News, Virginia, under the assumption that he and his crew would get better treatment from the Americans than the Canadians or British. Sutton boarded and escorted U-234 into Portsmouth, where she joined U-805, U-873, and U-1228.

U-234 was a large Type XB long-range cargo submarine that had left German-occupied Norway on 15 April en route to Japan with a cargo that included 1,200 pounds of uranium oxide, a disassembled Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter, a Henschel Hs-293 radio-controlled glide bomb, and other advanced electronics gear and weapons. U-234 was also carrying 12 passengers including a German Luftwaffe general, other German officers, civilian scientists and engineers, and two Japanese navy officers (see also H-Gram 033). Transiting under snorkel most of the way, U-234 surfaced on 10 May and received word of the German surrender for the first time. Believing it was Allied deception, U-234’s skipper was able to contact U-873’s commanding officer, who verified the message’s authenticity. U-234 then destroyed her sensitive communications and electronics gear and code materials, but couldn’t do anything about the cargo. Upon learning that U-234 intended to surrender, the two Japanese officers committed suicide and were buried at sea.

The arrival of U-234 in Portsmouth on 19 May with her high-ranking passengers created a press sensation, although the fact of the uranium oxide cargo was kept secret for many years. Although unconfirmed, the uranium oxide may have been used in the Manhattan Project, helping in developing the U.S. atomic bombs. U-235 was torpedoed and sunk as a target by Greenfish (SS-351) on 20 November 1947.

The Diehards

According to Morison, U-530 departed Norway on her seventh patrol and reached her operating area east of Long Island by early May (1,000 nautical miles east-northeast of Puerto Rico, according to the debrief of her skipper in Argentina after the war). U-530 conducted unsuccessful attacks on convoys both before and after the surrender announcement. Oberleutnant zur See Otto Wermuth, swayed by Nazi propaganda of the terrible fate that awaited should the Allies occupy Germany, opted to take his boat to Argentina, expecting a better reception and treatment. (Argentina, which had a sizable German population, remained neutral most of the war, only declaring war on Germany on 27 March 1945.)

U-530 reached Mar del Plata, Argentina, on 9 July after jettisoning her deck gun, torpedoes, ammunition, log books, crews’ identification, and anything else that might be considered sensitive. The length of her transit gave rise to decades of conspiracy theories that she carried gold and high-ranking Nazis (rumors included Adolf Hitler and his wife Eva Braun), none of which is true. The transit is easily explained in that much of it was submerged under snorkel, i.e., at a very slow speed.

On 17 August, a second U-boat arrived in Argentina. U-977 was a smaller Type VIIC submarine that had departed Norway on 2 May under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Heinz Schaeffer. He also opted to head toward Argentina rather than surrender after giving his married crewmen the option of going ashore, which 16 did in Norway on 10 May. U-977 then conducted what her skipper claimed was a 66-day transit under snorkel, supposedly the second longest by any German submarine. This claim differs from post-war debriefs, which include a stop in the Cape Verde Islands, but, regardless, it was a long, slow, mostly submerged transit.

Like U-530, U-977’s passage and arrival in Argentina stoked rumors of gold and Nazis. Actually, a number of high-ranking Nazis like Adolph Eichmann and Josef Mengele did make it to Argentina, several years later and incognito on passenger ships. None got there by submarine. (One of the more famous candidate submarines for taking Nazis to South America was the new Type XXI submarine U-3523, which wasn’t located until 2018, when it was discovered sunk off Denmark. It had been sunk by a British B-24 Liberator on 6 May 1945, but an erroneous position report by the plane threw off searchers for decades.)

Both U-530 and U-977 were initially considered suspects in the 5 July sinking of the Brazilian light cruiser Bahia. Bahia had exploded and sunk in about three minutes, before she could send an SOS. Her loss was unknown until 8 July when her relief arrived on station and didn’t find her. In a tragedy similar to that of the U.S. heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35) in the Pacific later that same month, survivors of the sinking drifted for days in the tropical sun and were subject to shark attacks. Only 34 men were rescued from a crew of 386 (the exact number of Bahia’s crew differs in various accounts). Among the dead were four U.S. Navy sailors, identified in one account as “radiomen” and in another as “sound technicians” (which is all I can find online). One of the Brazilian survivors recounted being in a raft with three Americans who all perished after a couple days. (Brazil had declared war on Germany on 21 August 1942, and there was extensive cooperation between the United States and Brazil against German submarine operations in the South Atlantic, including the U.S. provision that seven Canon-class destroyer escorts to be manned by Brazil.) The light cruiser Omaha (CL-4) provided medical assistance to Bahia survivors that had been picked up by British steamer Balfe.

An initial investigation by Argentina determined that it was not feasible in terms of time and distance for either U-530 or U-977 to have been responsible for sinking Bahia. A subsequent Brazilian-U.S. investigation determined the cause to be self-inflicted. During anti-aircraft gunnery practice, a 20-mm gunner firing on the target kite accidentally hit the depth-charge rack on the stern, resulting in a massive explosion of the depth charges and sinking the ship in a matter of minutes.

Much to the consternation of the commanders of U-530 and U-977, the Argentines turned them, their crews, and the submarines over to the United States. U-977 was ultimately sunk as a target by U.S. submarine Atule (SS-403) on 13 November 1946. U-530 was sunk as a target on 28 November 1947 by U.S. submarine Toro (SS-422).

Under the terms of the unconditional surrender, all German submarines were to be turned over to the Allies to be destroyed, although provision was made for Allied nations to study some of them before sinking them. German crews sabotaged and sank many of their submarines themselves. The British intended to sink 116 U-boats northwest of Ireland in an operation called Deadlight, which took place from November 1945 to February 1946. However, 56 of them were in such bad shape that they sank under tow on the way there; most of the rest were sunk by surface gunfire. The United States also scuttled all U-boats in its possession except U-505, thanks to Rear Admiral Daniel V. Gallery, who had commanded the Guadalcanal hunter-killer group. Because U-505 had been “captured” and not “surrendered,” the boat could be spared, and was donated to the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry in 1954.

The Type XXI Submarine U-2513 was one of five Type XXI submarines ready for combat at the end of the war. She was surrendered in German-occupied Norway and transferred to the U.S. Navy in August 1945 in order to study her very advanced design. The Type XXI was the first submarine in any navy to be designed to operate primarily underwater (these were the first submarines that were faster underwater than on the surface), rather than as a low-visibility surface ship that could submerge. The Type XXI, with its new hull design optimized for underwater speed, greatly increased battery capacity that could enable several days of submerged operations, and numerous other technical innovations, was the most advanced submarine in the world. The U.S. Navy operated U-2513 from 1945 to 1949 and many of her design features were incorporated in the Greater Underwater Propulsion Power Program (GUPPY) for U.S. submarines and in the first nuclear-powered submarine Nautilus (SSN-571). President Harry S. Truman submerged aboard U-2531, becoming the second U.S. President to get underway on a submarine. U-2513 was sunk as a target off Key West on 7 October 1951 during rocket tests by destroyer Robert A. Owens (DDE-827).

Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz remained German head of state in what was termed the Flensburg Government until it was dissolved by the Allies on 23 May 1945. He would subsequently be tried at Nuremburg for major war crimes. He was found not guilty of committing crimes against humanity, but was found guilty committing crimes against peace and crimes against the laws of war. Maybe a lawyer can tell the difference, but, regardless, he only spent ten years in prison and died in 1980.

Numbers vary on how many U-boats were lost, but of about 1,160 built, about 780 were lost to all causes, about 640 to combat at sea, with a loss of at least 28,000 crewmen killed and 5,000 captured. About 430 U-boats were lost with all hands and about 215 didn’t survive their first patrol. The U-boats sank about 2,800 Allied ships, including 158 British Royal Navy and 30 U.S. warships. Over 700 Allied aircraft (mostly British) were lost on anti-submarine sorties. Leftover mines continued to inflict ship losses and casualties for years after the end of the war. Well over 30,000 Allied merchant marine sailors died. The cost to both sides in the Battle of the Atlantic was extremely steep.

On 28 May 1945, the U.S. Navy and British Royal Navy issued a joint statement: “Effective at 2001 this date, Eastern Standard Time (0001 29 May Greenwich Mean Time) no further trade convoys will be sailed. Merchant ships by night will burn navigation lights at full brilliancy and need not darken ship.”

Sources include: “Kill or Be Killed? The U-853 Mystery” by Adam Lynch, in Naval History Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 2, June 2008; “Operation Teardrop Revisited” by Philip K. Lundeberg, in To Die Gallantly: The Battle of the Atlantic, edited by Timothy J. Runyan and Jan M. Copes (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994); “The Treatment of Survivors and Prisoners of War, at Sea and Ashore” by Dr. Philip K. Lundberg, in International Journal of Naval History, Vol. 13, Issue 1, April 2013; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. X: Victory in the Atlantic, by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1956); NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships; u-boat.net is also a very useful site.