H-022-5: Battle of Vella Lavella—The Last Japanese Victory, 6–7 October 1943

H-Gram 022, Attachment 5

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

October 2018

On the night of 6-7 October 1943, a force of three U.S. destroyers attacked nine Japanese destroyers northwest of the island of Vella Lavella in the central Solomons. Despite advantages of radar, the new combat information centers (CIC) aboard U.S. ships, and improved doctrine, valor, and audacity could not overcome numbers or the superior capabilities of Japanese torpedoes. The Battle of Vella Lavella would be the last major battle of the Central Solomons campaign, and would also be the last significant Japanese victory of the war.

After the costly campaign to take the island of New Georgia in the central Solomon Islands chain, the Third Fleet commander, Vice Admiral William Halsey, had to decide what to do next. Having fought a pretty effective delaying action on New Georgia, the Japanese had pulled another disappearing act (as at Guadalcanal) and withdrawn the remains of their forces across the Kula Gulf to the island of Kolombangara to the northwest of New Georgia, which had also been reinforced. Halsey was concerned that at the current rate of advance up the Solomon chain, it would take years to get to the major Japanese base at Rabaul, let alone Tokyo. With the approval of both Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur, Halsey opted to leap-frog over Kolombangara to the relatively lightly defended island of Vella Lavella, which lies to the northwest of Kolombangara across Vella Gulf. Over the next months, numerous naval battles with no names occurred as the Japanese tried to withdraw their forces from Kolombangara and reinforce Vella Lavella. Most of these involved U.S. PT-boat attacks on Japanese barges, along with near-constant air battles overhead, during which the Japanese suffered increasingly disproportionate losses as better U.S. aircraft, and attrition of the best Japanese pilots, had their effect.

During an engagement sometimes referred to as the Battle of Horaniu on 17 August 1943, a force of four U.S. destroyers (Nicholas [DD-449)], O’Bannon [DD-450], Taylor [DD-468], and Chevalier [DD-451]) under Captain Thomas J. Ryan, attempted to engage a force of four Japanese destroyers that were protecting about 20 barges and small auxiliaries attempting to withdraw Japanese troops from Kolombangara. The result was an ineffective exchange of torpedos and gunfire as the Japanese commander, Rear Admiral Baron Matsui Ijuin (92nd in his class of 96 at the Japanese naval academy), opted to flee rather than fight—uncharacteristic of Japanese commanders and to the frustration of Ryan who was itching for a fight. As in many of the other lesser actions, going after the barges was like stomping cockroaches and Ryan’s force sank four small auxiliaries, but most of the barges got away. Despite the inconclusive nature of the battle, the skipper of Chevalier, Lieutenant Commander George R. Wilson, was awarded a Navy Cross for his aggressive actions during the battle. Ultimately the Japanese would successfully evacuate 9,000 troops (most of their force) from Kolombangara despite constant air and PT-boat attacks on the barges.

After the Allied landing on Vella Lavella, the Japanese quickly reached the conclusion that reinforcing the island would be a loser, so they opted to hold the island as long as possible with the relatively few forces there, with the intent to withdraw them at the last moment, which they mostly succeeded in doing. By the beginning of October 1943, Japanese forces on the island were down to just under 600 men, and U.S. and New Zealand troops were closing in on the Japanese foothold on the northwest side of the island. Accordingly, Ijuin received orders to withdraw the last of the Japanese troops on Vella Lavella.

Ijuin assembled a relatively strong force of three older destroyer-transports and 20 barges and small auxiliaries, protected by six modern destroyers, to accomplish the mission. U.S. Navy intelligence, as well as sighting reports by scout planes and coast watchers, assessed that a force of nine destroyers would be coming down the “Slot” on the night of 6–7 October to Vella Lavella. This presented the commander of Task Group 31.2, Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson (who had relieved Rear Admiral Kelly Turner in July) with a dilemma as only three U.S. destroyers (Selfridge [DD-357], Chevalier, and O’Bannon) were patrolling in the Slot at the time. Wilkinson opted to detach three additional destroyers from convoy duty south of the Solomons and have them rendezvous with the other three destroyers to interdict the Japanese force. Unfortunately, the Japanese got to the rendezvous point first.

The U.S. destroyer force was under the command of Captain Frank R. Walker, Commander Destroyer Squadron 4, who had distinguished himself as commanding officer of the destroyer Patterson (DD-392), one of the few destroyers that managed to get underway during the attack on Pearl Harbor. The force consisted of Selfridge (with Walker embarked), Chevalier, and O’Bannon. All three ships were battle veterans. All three had the latest, most capable SG-type surface-search radar, and, although the combat information center concept was still a work in progress, all three had some version of a CIC. The ability to integrate radar and all sources of information into a coherent plot had progressed to the point that Walker opted to fight the battle from CIC rather than the bridge, a “first” from what I have been able to find.

The CIC concept had progressed rapidly since the commanding officer of USS Fletcher (DD-445), Commander Cole, and his executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Wiley, had created an ad hoc CIC prior to the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on 13 November 1942. Fletcher had emerged unscathed from that horrific battle as well as from the debacle at Tassafaronga that followed two weeks later, partly due to superior situational awareness afforded by the CIC. Although Fletcher was the first to create a CIC, others had already been thinking about the concept, and, in November 1942, Admiral Nimitz issued “Tactical Bulletin 4TB-42,” which directed all Pacific Fleet ships to create a CIC aboard ship. Initially, how to do this was left up to the individual ship’s commanding officer, which resulted in a variety of approaches, some of which worked better than others. CNO King held a conference in Washington, DC, in January 1943, with the intent to extend the CIC concept from the Pacific Fleet to the entire Navy. Throughout 1943, Nimitz’ staff officer for destroyers, Rear Admiral Mahlon S. Tisdale, led the effort to create CICs aboard ship. Tisdale, a survivor of the defeat at Tassafaronga, had learned and incorporated many lessons from that and other battles around Guadalcanal. In June 1943, Tisdale issued a new manual, the “CIC Handbook for Destroyers,” which codified the CIC concept, but still left ample opportunity for experimentation by ships’ commanding officers. At Vella Lavella, Walker’s ships had rapidly incorporated as much of the CIC concept as they could (without going into a shipyard). The improved situational awareness was a major factor in Walker’s decision to give battle, despite the odds.

The basic set-up for the battle was that the Japanese force approached Vella Lavella from the northwest, while Walker’s destroyers were transiting westerly north of the island. Southwest of Vella lavella and transiting northerly were three destroyers under the command of Captain Harold O. Larson, USN. The Ralph Talbot (DD-390), with Larson embarked, Taylor, and La Vallete (DD-448) had been detached from convoy duty, intending to rendezvous with Walker’s force northwest of Vella Lavella before the Japanese arrived. Larson’s force did not get there in time.

The Japanese split their force, with the three destroyer-transports, escorted by two destroyers, proceeding ahead, while the pack of barges and auxiliaries transited in a third group. Walker’s force was dogged by a Japanese “Pete” scout float plane that kept dropping flares over the U.S. force. Walker made the correct assumption that he had lost any element of surprise.

Radar in Walker’s group detected the lead Japanese force at 2231 at a range of 10 miles. Japanese lookouts sighted Walker’s force at 2235. Walker attempted to raise Larson via TBS (talk-between-ships) without success, as the distance between to two U.S. destroyer groups was still too great. Believing he was up against nine Japanese destroyers, Walker decided to attack anyway with the intent to herd or draw the Japanese toward Larson’s destroyers, which would make the odds two to one instead of three to one. In reality, the odds were better than Walker assumed as soon as Walker’s force was sighted, the three destroyer-transports were ordered to exit the area to the northwest. The two escorting destroyers, Shigure (veteran of many battles and sole survivor of two) and Samidare, made haste to rejoin the other four Japanese destroyers, but hadn’t quite done so when battle was joined. So, at the start of the engagement, it was three U.S. destroyers versus one group of two Japanese destroyers and another group of four Japanese destroyers.

Rear Admiral Ijuin believed he was up against a much larger force than he actually was. The Japanese scout plane had reported four U.S. cruisers and three destroyers. As the battle commenced, Ijuin blew a chance to cross the U.S. “T” because he misjudged the size of the U.S. ships (thinking they were cruisers) and therefore misjudged distance. In the confused maneuvers that followed, the Japanese destroyer Yugumo charged the U.S. destroyers by herself, a brave act that, however, fouled the range for the other Japanese destroyers, preventing them from launching torpedoes at the optimum time. As the closest target, Yugumo drew fire from all three U.S. destroyers. At 2255, the U.S. destroyers fired 14 torpedoes at Yugumo, and opened fire with guns at 2256. Yugomo fired eight torpedoes at the U.S. destroyers before she was hit at least five times by U.S. shells, which knocked out her steering. At 2301, the Chevalier (second in line) was hit by one of Yugumo’s torpedoes. Shortly after, at 2303, Yugumo was hit by one of the slower U.S. torpedoes (which actually worked,) and she sank at 2310.

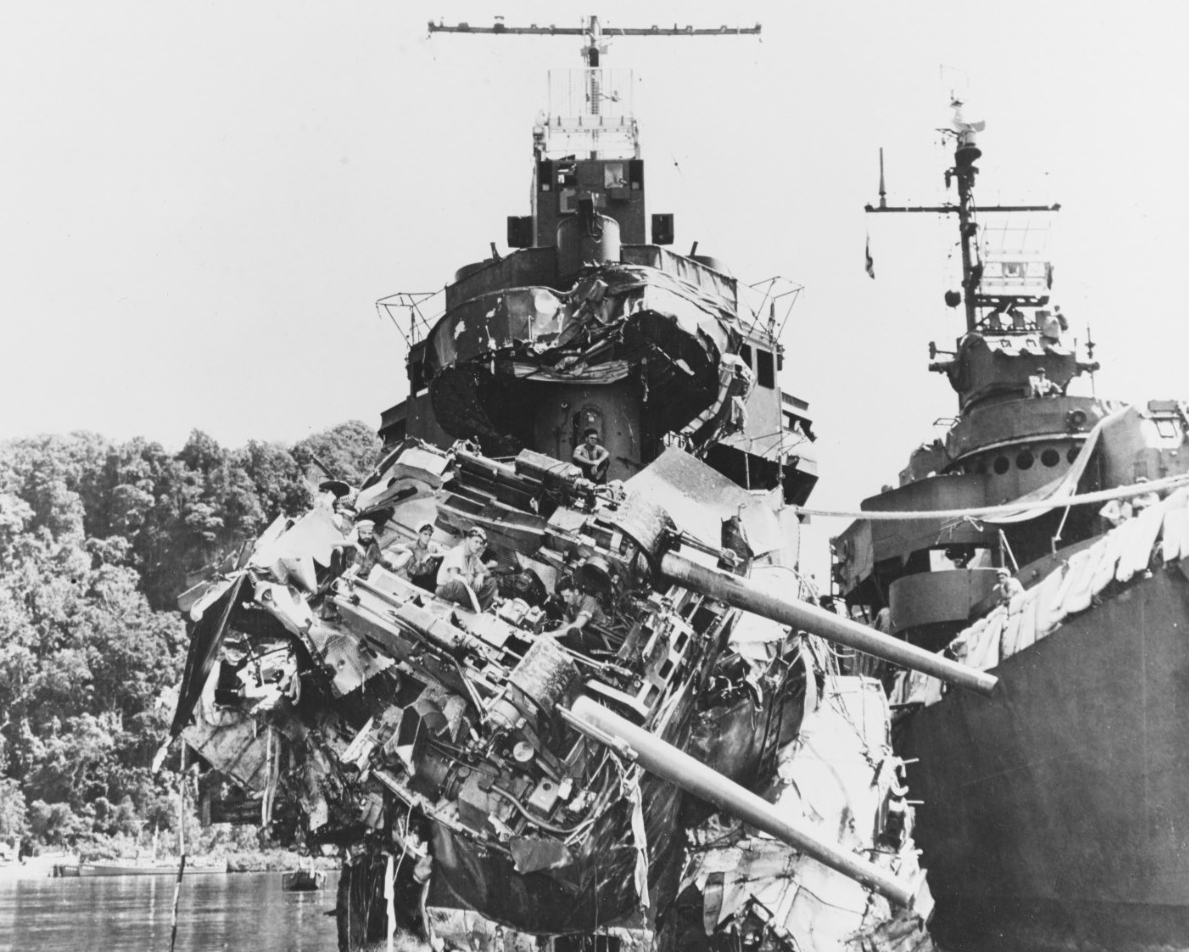

The torpedo that struck Chevalier detonated the forward magazine, which blew the whole bow off forward of the bridge. Chevalier’s stern jackknifed into the path of the trailing O’Bannon, which, blinded by the smoke of battle, was unable to avoid colliding with Chevalier’s wrecked stern. The two ships were entangled and locked together, taking both out of the battle. Walker, aboard Selfridge, the lead destroyer, continued to press the attack against what he now assumed were nine-to-one odds. Selfridge engaged the group of two Japanese destroyers until 2306, when she was hit by one of 16 torpedoes fired by Shigure and Samidare. Although not quite as devastating a hit as that on Chevalier, Selfridge went dead in the water with severe damage to her bow and forward sections (that her magazine didn’t explode was extraordinary luck—see photo above).

With all three U.S. destroyers dead in water, and five of his own destroyers still pretty much unscathed, Ijuin decided it was time to quit. His decision was bolstered by a sighting report from a Japanese float-plane scout that reported the approach of Larson’s three destroyers from the south, again misidentified as a cruiser-destroyer force. At 2317, Ijuin’s destroyers fired a parting shot of 24 torpedoes at the crippled U.S. destroyers, all of which missed. Ijuin’s “victory” would be the last surface victory for the Imperial Japanese Navy for the rest of the war. Ijuin would claim that his force sank two U.S. cruisers and three destroyers. Walker, on the other hand, reported sinking three Japanese destroyers and believed that he was the victor. However, in the heat of the destroyer battle, the Japanese barges and auxiliaries had managed to get into Vella Lavella and successfully extract the last 589 Japanese troops on the island. Thus, the Japanese accomplished their mission at the cost of one destroyer and 138 dead.

Larson’s destroyer force arrived at 2335, but the Japanese were already gone. Despite heroic damage control on the Chevalier, it quickly became apparent that she could not be saved. O’Bannon took aboard about 250 survivors from Chevalier (made easier with O’Bannon alongside). After O’Bannon untangled from Chevalier, the La Vallete dispatched Chevalier’s stern with a torpedo at 0300 and then sank her floating bow with depth charges. Selfridge regained power and backed out of the battle area. U.S. casualties were 54 killed on Chevalier and 13 killed on Selfridge, with an additional 36 missing from the two ships, who would eventually be declared dead. O’Bannon left behind boats that rescued 25 Japanese sailors the next morning; another 78 Japanese were rescued by U.S. PT boats—an unusually large number who gave themselves up. Although heavily damaged, O’Bannon would continue her charmed life and go through the entire war, earning 17 Battle Stars (including for the bloody 13 November 1942 battle off Guadalcanal), the most of any destroyer), a Presidential Unit Citation, and not a single Purple Heart.

Captain Frank Walker would be awarded the Navy Cross for his audacious action against a much larger Japanese force. The skipper of Selfridge, Lieutenant Commander George E. Packham, in command for all of four days, would receive a Silver Star. Rear Admiral Ijuin would survive the sinking of the Japanese light cruiser Sendai during the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay in November 1943, being rescued by a Japanese submarine, but his luck would run out when his flagship (a patrol boat) at Saipan was torpedoed and sunk in 1944.

Sources include: History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. VI: Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier by Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison; “The Evolution of the US Navy into an Effective Night Fighting Force During the Solomons Islands Campaign 1942–1943,” Jeff T Reardon, Ph.D. dissertation, August 2008, University of Ohio; Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the US Navy, 1898–1945 by Trent Hone (2018), Naval Institute Press; Information at Sea: Shipboard Command and Control in the US Navy, from Mobile Bay to Okinawa by Captain Timothy S. Wolters, USNR, (2013), Johns Hopkins University Press.

(Back to H-Gram 022 Summary)