H-008-1: World War I 100th Anniversary

H-Gram 008, Attachment 1

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

July 2017

So you think your OPNAV tour was tough? On 25 June 1917, Captain William V. Pratt (future CNO, 1930–33) assumed the duties of Assistant Chief of Naval Operations after the untimely death of Captain Volney Chase due to exhaustion. The pace of operations and the accomplishments of the U.S. Navy in the opening months of the war were profound, particularly considering much contingency planning had been forbidden by the Wilson administration in the lead-up to the war so as not to compromise U.S. neutrality.

On 26 June 1917, the first convoy transporting troops of the American Expeditionary Force (14,000 total, including 2,700 Marines,) escorted by the U.S. Navy, began arriving in St. Nazaire, France only two and a half months after the U.S. declared war on Germany. Taken for granted today, the transport of that many troops in so short a time was an astonishing feat in 1917 and shocked the German high command, which had assured the Kaiser that even if the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare caused the U.S. to enter the war on the side of the Allies, there was no way that the United States could get the U.S. Army (then about 17th largest in the world) through the submarine blockade to Europe before the spring of 1918. With Czarist Russia knocked out of the war in the spring of 1917, the German plan was to shift hundreds of thousands of troops from the Russian Front to the Western Front and deal a knock-out blow to the French and British before the U.S. could get into the fight. Actually, the German high command was almost right; the vast majority of American troops didn’t begin to arrive in Europe until after the great German offensive in the spring of 1918 had already reached its culminating point. However, the arrival of U.S. troops in June 1917 provided a huge boost to Allied morale and resolve, and the subsequent arrival of vast quantities of war material protected by the U.S. Navy had significant impact on the Allies’ ability to hold out until the arrival of 2 million American troops in 1918, which turned the tide and caused the Germans to sue for an armistice.

U-Boats Visit the United States

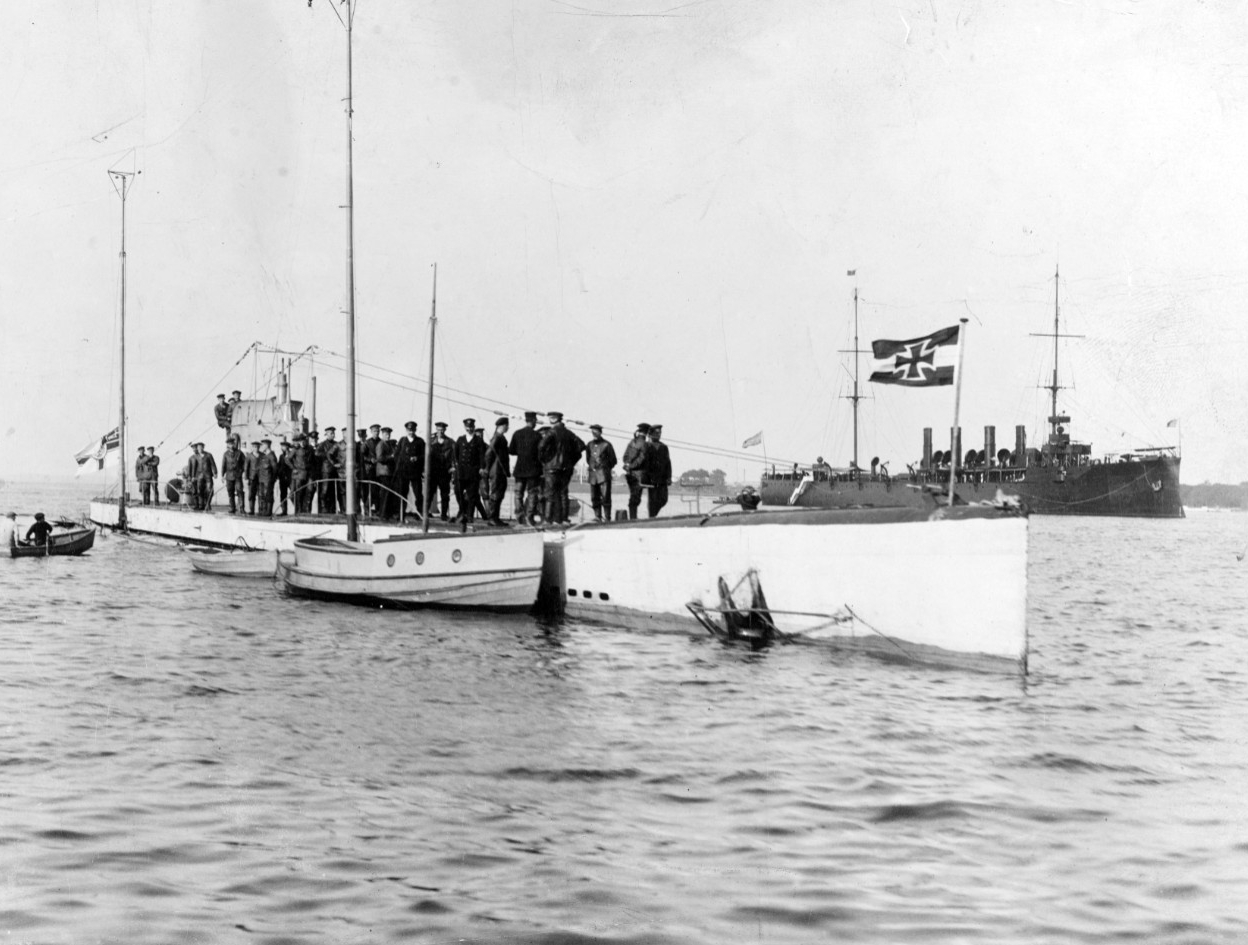

In a previous H-Gram, I described how the first U.S. destroyers arrived at Queenstown, Ireland, on 4 May 1917—the first U.S. combat forces to reach the European theater—and that the decision to send the destroyers was very controversial within senior leadership of the U.S. Navy. Primary concerns included the fear that sending destroyers to Europe would leave the U.S. East Coast and the U.S. Battle Fleet unprotected against U-boat attack. Although German U-boats did not begin sinking ships off the East Coast until the spring of 1918, the concerns were not unfounded. In fact, two U-boats had already visited U.S. ports, much to the consternation of the U.S. Navy. The first was the German submarine Deutschland, a very large submarine built as a “merchant submarine” (but converted to an attack submarine later in the war), which showed up at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, by surprise, on 9 July 1916, made a port call in Baltimore (with much press hoopla and a warm public welcome), then left with a cargo of critical strategic materials (tin, nickel, and rubber), and avoided several British and French cruisers that arrived off the Virginia Capes in an attempt to intercept the sub. The British were not amused by this successful effort to avoid the blockade of Germany.

Then, on 7 October 1916, U-53 brazenly entered Newport, Rhode Island, and anchored for a port call, also completely by surprise. While the U-boat’s skipper, Kapitanleutnant Hans Rose, paid a courtesy call on Rear Admiral Austin Knight, commander of the naval district, boats filled with curious Newport civilians swarmed the U-boat, and many made it onboard (including a reporter) and were given tours inside the boat. Rose also paid a call on Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, commander of the U.S. Destroyer Force, onboard his flagship, the scout cruiser Birmingham (CS-2.) Knight and Gleaves (with his wife and daughter) then paid a reciprocal call onboard the U-boat. Under naval protocol at the time, it was perfectly legal for a foreign warship to pay a call in a neutral port, as long as it did not stay more than 24 hours. A port call by a combat U-boat, however, was unprecedented, and the wires burned between Newport and Washington, DC, seeking guidance. Before nightfall, Knight ordered the U-boat to leave and the circus ended. However, the next day, U-53 sank five merchant ships just outside U.S. territorial waters while a large number (16) of U.S. destroyers looked on, with no authority to do anything about it except rescue 216 survivors from the British, Canadian, Dutch, Norwegian, and U.S. merchant ships (the U.S. merchant ship West Point had gone down before the destroyers arrived on the scene). U-53 used traditional “cruiser rules” for sinking the merchant ships: surfacing, firing a shot across the bow, reviewing the ship’s papers, and, if “contraband” was found, ordering the crew into lifeboats and sinking the ship with deck gun, torpedo, or demolition charge (U-53 used all three methods, expending a torpedo on the Canadian liner Stefano, which refused to sink despite gunfire and explosive charge). The sinkings, despite no loss of life, provoked outrage that soured any goodwill generated by the two port calls, and resulted in an embarrassment within the U.S. Navy over the German submarines’ ability to act with impunity. When the Deutschland returned for a second visit to the United States on 1 November 1916, to New London, she received a very unfriendly reception and also collided with a tug while departing, killing five U.S. seamen. The Germans had definitely worn out their welcome. The next U-boat to reach the U.S. East Coast, U-151 in May 1918, would not make a port call, but would turn her torpedoes and guns on U.S. merchant shipping.

U.S. Anti-Submarine Actions in European Waters, May–June 1917

Despite internal Navy opposition to sending destroyers to Europe, the Navy did so, and by June 1917 over 30 U.S. destroyers were operating in the Western Approaches to Great Britain and the Bay of Biscay off France against German U-boats. As of 21 May, the British had (finally) adopted the convoy system as the best means to combat U-boat attacks rather than fruitlessly patrolling in open waters. U.S. destroyers were immediately integrated into the British convoy system. In the first weeks, although there were several encounters with U-boats, real and imagined, the U.S. destroyers mostly rescued survivors from ships sunk by U-boats that were not protected by convoy.

On 21 May 1917, Ericsson (DD-56) launched a torpedo at a surfaced U-boat that was shelling a Norwegian and a Russian sailing vessel, the first torpedo fired by the U.S. Navy at an enemy in the war. The torpedo missed. The U-boat dived and sank the two sailing vessels with torpedoes of its own, leaving Ericsson to rescue survivors.

On 4 June 1917, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Olaf Gullickson, commanding the Naval Armed Guard on board the U.S. steamship Norlina, opened fire on U-88, just as Norlina was hit by a torpedo. Despite two hits, U-88 survived. (The U-boat’s skipper was Kapitanleutnant Walter Schwieger, who as skipper of U-20 had sunk the British liner Lusitania in May 1915. U-88 would hit a mine and be lost with all hands, including Schwieger, in September 1917.) For his quick action, Gullickson would be awarded the Navy Cross, the first of the war (I think.)

On 16 June 1917, O’Brien (DD-51) depth-charged and slightly damaged a German submarine. The British were so thrilled (thanks to intercepting and reading German codes) that Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, Commander-in-Chief of the Western Approaches, put the O’Brien’s commander, Lieutenant Commander Charles A. Blakely, in for the British Distinguished Service Order (Blakely was also awarded a U.S. Distinguished Service Medal for the same action) and Ensign Henry N. Fallon for a British Distinguished Service Cross (not a bad haul for a near-miss.) Fallon would later receive a Navy Cross for action with another U-boat in September 1917.

U.S. Naval Aviation Arrives in European Theater

On 5 June 1917, the initial elements of the U.S. Navy First Aeronautic Detachment, commanded by Lieutenant Kenneth Whiting (yes, namesake of Whiting Field near Pensacola,) arrived in France aboard the collier Neptune (AC-8), while a second element arrived three days later on the collier Jupiter (AC-3,) which would later be converted to the first U.S. aircraft carrier, Langley (CV-1). The detachment, consisting of seven officers and 122 enlisted men, commenced training on French aircraft, experiencing their first fatality on 28 June 17, when Thomas W. Barrett was killed in an air crash at Tours, France. Barrett was the first U.S. Navy member killed in France in World War I.

First U.S. Troop Convoy to Europe

On 14 June 1917, the first American Expeditionary Force (AEF) convoy, with 14,000 troops (Army and Marines), departed from New York City in four groups bound for St. Nazaire, France, under the overall command of Rear Admiral Gleaves (see U-53 incident above). Each group consisted of three or four troopships (including Dekalb—ID-3010—formerly the commandeered German liner/auxiliary cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich, which had been interned in Norfolk in March 1915 following seven months as a commerce raider in which she sank, among others, the U.S. schooner William P. Frye in January 1915, the first U.S.-flagged ship sunk in the war). Each of the groups was also escorted by an armored cruiser (Seattle—CA-11), protected cruiser (Charleston— CA-19—and St. Louis—CA-20), or a scout cruiser (Birmingham—CS-2), and three destroyers each. The oilers Kanawha (AO-1) and Maumee (AO-2) provided underway refueling (which had been done only for the first time on 28 May) for the escorting destroyers. Group 3 also included the armed collier Cyclops (AC-4), which would become famous for disappearing without a trace in the “Bermuda Triangle” in March 1918.

As each group approached the Western Approaches/Bay of Biscay, additional U.S. destroyers operating out of Queenstown, Ireland, augmented the escorts. Although there were several reported torpedo attacks (which were probably imaginary), none of the ships was hit by U-boats. On 26 June, while escorting Group 2, Cummings (DD-44) spotted a submarine and dropped a depth charge, bringing considerable oil and debris to the surface. Although the U-boat apparently survived, the British richly awarded Cummings with a Distinguished Service Order for the CO, Lieutenant Commander George P. Neal, and a Distinguished Service Cross and Distinguished Service Medals for other crew.

On 26 June, Group 1 anchored in the Loire River off St. Nazaire, France, and immediately began disembarking troops. This was to lead to one of the most famous quotes of the war, “Lafayette, we are here!” by AEF Commander Major General John J. Pershing’s “designated orator,” Colonel C. E. Stanton, in Paris on 4 July 1917. Of note, before Vice Admiral William S. Sims (Commander U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters) went to greet Pershing, he removed his newly acquired third star so as not to upstage the AEF commander, who had yet to to receive his promotion.

(My thanks to Dr. Frank Blazich, former NHHC historian, for his research and World War I chronology; to Dr. Dave Kohnen, NHHC Naval War College Museum Executive Director, for his original research on William S. Sims; and Matt Cheser, NHHC historian, for his research on the first AEF convoy. Also, the book America’s U-Boats by Chris Dubbs has the best accounts of German U-boat visits to the United States.)