Doolittle Raid

18 April 1942

Conceived in January 1942 in the wake of the devastating Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the “joint Army-Navy bombing project” was to bomb Japanese industrial centers, to inflict both “material and psychological” damage upon the enemy. Planners hoped that the former would include the destruction of specific targets “with ensuing confusion and retardation of production.” Those who planned the attacks on the Japanese homeland hoped to induce the enemy to recall “combat equipment from other theaters for home defense,” and incite a “fear complex in Japan.” Additionally, it was hoped that the prosecution of the raid would improve the United States’ relationships with its allies and receive a “favorable reaction [on the part] of the American people.”

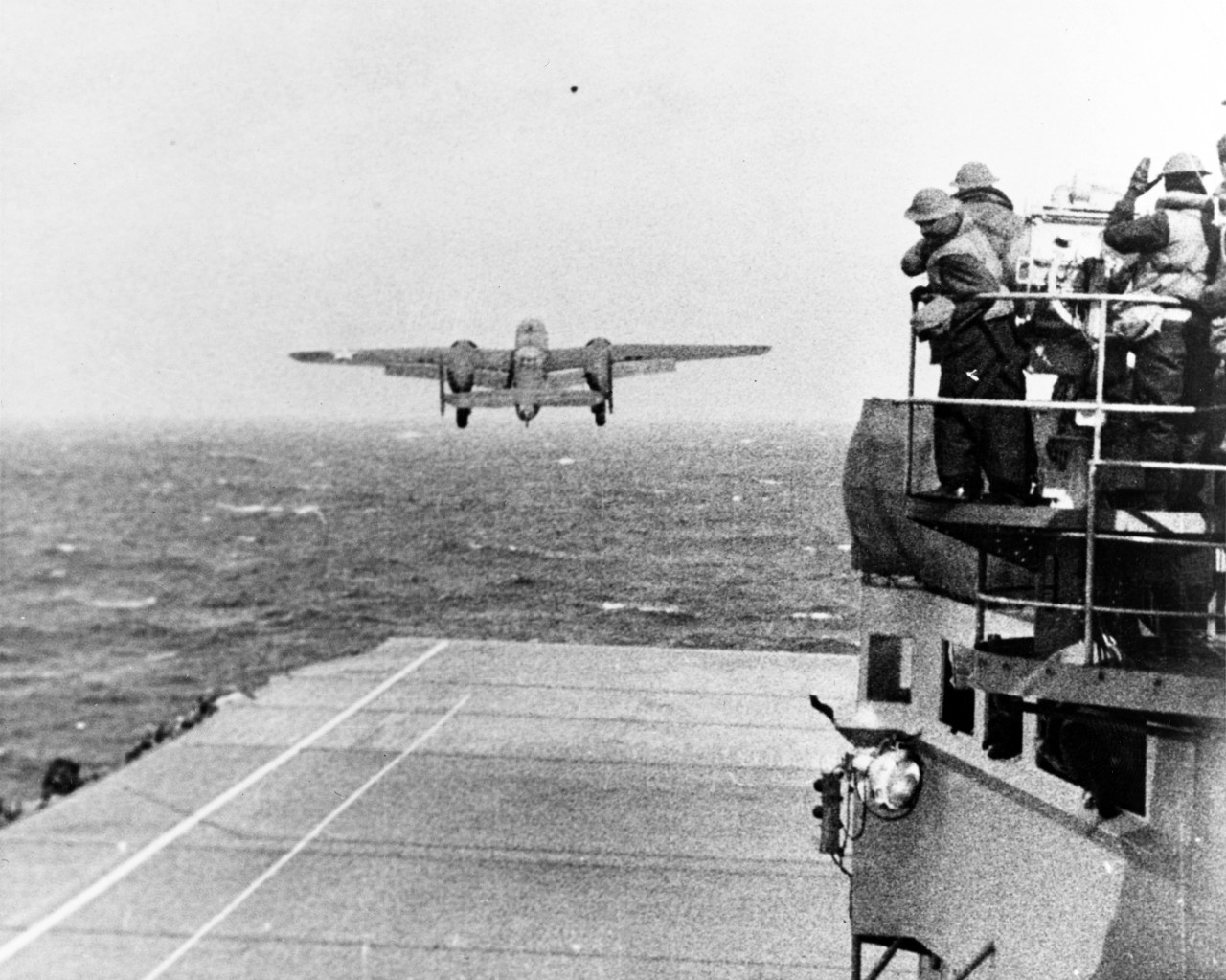

Originally, the concept called for the use of U.S. Army Air Force bombers to be launched from, and recovered by, an aircraft carrier. Research disclosed the North American B-25 Mitchell to be “best suited to the purpose,” the Martin B-26 Marauder possessing unsuitable handling characteristics and the Douglas B-23 Dragon having too great a wingspan to be comfortably operated from a carrier deck. Tests off the aircraft carrier Hornet (CV-8) off Norfolk, and ashore at Norfolk soon proved that although a B-25 could take off with comparative ease, “landing back on again would be extremely difficult.”

The attack planners decided upon a carrier transporting the B-25s to a point east of Tokyo, whereupon it would launch one pathfinder to proceed ahead and drop incendiaries to blaze a trail for the other bombers that would follow. The planes would then proceed to either the east coast of China or to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. However, Soviet reluctance to allow the use of Vladivostok as a terminus and the Stalin regime’s unwillingness to its neutrality with Japan compelled the selection of Chinese landing sites. At a secret conference at San Francisco, Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle, USAAF, who would lead the attack personally, met with Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., who would command the task force that would take Doolittle’s aircraft to the very gates of the Japanese empire. They agreed upon a launch point some 600 miles due east from Tokyo, but, if discovered, Task Force 16 (TF-16) would launch planes at the respective point and retire.

Twenty-four planes drawn from the USAAF's 17th Bombardment Group were prepared for the mission, with additional fuel tanks installed and “certain unnecessary equipment” removed. Intensive training began in early March 1942 with crews who had volunteered for a mission that would be “extremely hazardous, would require a high degree of skill and would be of great value to our defense effort.” Crews practiced intensive cross-country flying, night flying, and navigation, as well as “low altitude approaches to bombing targets, rapid bombing and evasive action.”

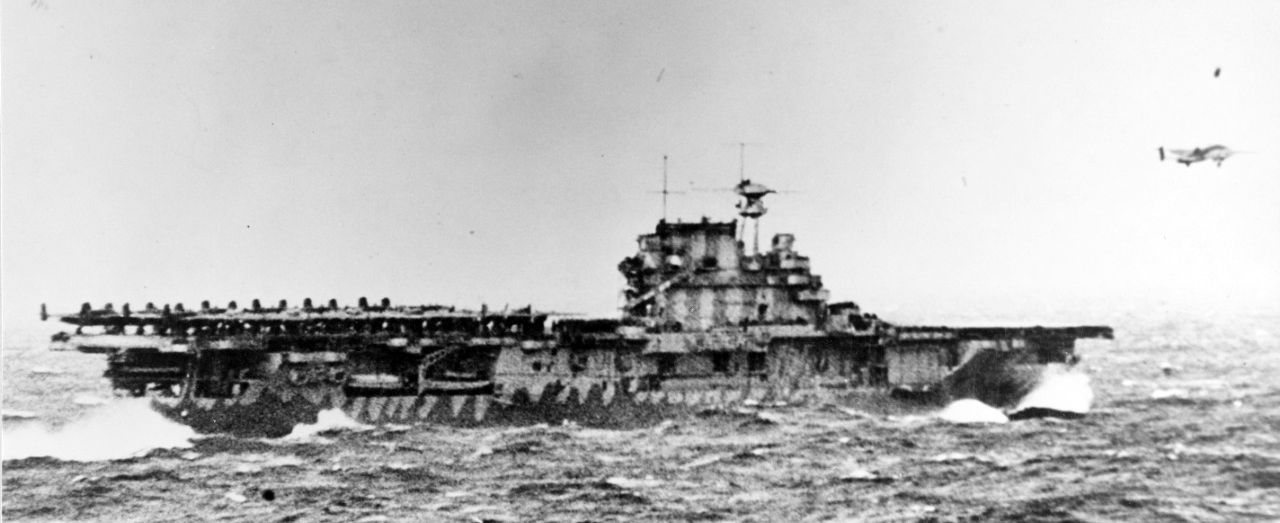

Lieutenant Henry L. Miller, USN, oversaw the carrier take-off practice at Eglin Field, Florida, work that elicited praise from Doolittle for Miller’s “tact, skill and devotion to duty.” With everything not deemed essential stripped from the planes, Hornet loaded 16 B-25s (all that could be shipped) on board at Alameda (31 March–1 April 1942) and sailed to rendezvous with the carrier Enterprise (CV-6) to form part of Halsey’s TF-16.

The Japanese, monitoring U.S. Navy radio traffic, deduced that a carrier raid on the homeland was a possibility after 14 April 1942 and prepared accordingly. TF-16 approached to within 650 miles of Japan on 18 April 1942. Lacking radar, the Japanese “early warning” capability lay in parallel lines of picket boats—radio-equipped converted fishing trawlers—operating at prescribed intervals offshore. One of these little vessels, No.23 Nitto Maru, discovered the task force on the morning of 18 April and radioed a sighting report. Although Halsey had agreed to take TF-16 within 400 miles of Japan to ensure maximum success, as Doolittle had requested while en route, the admiral recognized the potential threat of Japanese land-based air assets (indeed, 80 medium bombers had been massed in the Kanto area) to half of the U.S. Navy’s carrier force in the Pacific. The exigencies of war dictated that Halsey order Hornet to launch the 16 Mitchells earlier than planned.

The Japanese 26th Air Flotilla, expecting the Americans to approach within 200 miles of Japan as they had done in the raids in February and March on Wake and Marcus, and in the Marshalls and Gilberts, launched 29 medium bombers equipped with torpedoes from Kisarazu, escorted by 24 carrier fighters equipped with long-range tanks, to find TF-16.

The unexpected employment of long-range U.S. Army bombers, however, took the Japanese by surprise. Taking a little over an hour to launch, Doolittle’s B-25s, carrying high-explosive and incendiary bombs, flew on and hit targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya, against negligible opposition. One B-25’s ordnance damaged the aircraft carrier Ryuho (being converted from the submarine depot ship Taigei) at Yokosuka and thus delayed her completion. Of the 16 B-25s, 15 crashed in occupied China, where the Japanese inflicted brutal reprisals against the Chinese populace who had sheltered the American airmen. The Japanese also managed to capture the survivors of two crews, later executing three of them. One B-25 landed intact at Vladivostok, where the Soviets interned the aircraft and its crew.

That same day, in a series of actions often overlooked when compared to the B-25 raids, planes from Enterprise attacked Japanese picket boats encountered near TF-16, damaging the armed merchant cruiser Awata Maru and the guardboats Chokyu Maru, No.1 Iwate Maru, No.2 Asami Maru, Kaijin Maru, No.3 Chinyo Maru, Eikichi Maru, Kowa Maru, and No.21 Nanshin Maru. Guardboats No.23 Nitto Maru (which had transmitted the initial contact report) and Nagato Maru, also damaged by planes from Enterprise, were sunk by gunfire of the light cruiser Nashville (CL-43). Japanese antiaircraft fire damaged one Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless, which ditched near the disposition, a destroyer rescuing the crew. The next day (19 April), No.21 Nanshin Maru, previously damaged by Enterprise planes, was scuttled by gunfire of the light cruiser Kiso; No.1 Iwate Maru sank as the result of damage inflicted by Enterprise planes on the day before. The Doolittle Raid had temporarily put that portion of the Japanese navy’s offshore warning network out of commission. Moreover, the U.S. Navy’s carriers had been able to operate in waters of their own choosing, uncontested by the Japanese, whose frustration had increased correspondingly with their inability to engage the Americans.

All told, in addition to the aforementioned air units from 26th Air Flotilla, the Japanese navy’s Combined Fleet deployed 11 boats from the 3rd and 8th Submarine Squadrons, in addition to two cruiser divisions, to intercept TF-16. Meanwhile, the First Air Fleet, returning from the Indian Ocean, formed around carriers Akagi, Soryu, and Hiryu, on 18 April 1942 in the Bashi Channel, south of Formosa, received orders to engage the Americans. None of the considerable forces deployed to attack TF-16 were able to find the retiring force and bring it to battle. Search efforts continued, without success, until 24 April.

Although the material damage inflicted by Doolittle’s raiders proved small and the early-warning picket line would be restored by an infusion of vessels to replace the ones lost, the effect of the air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed “unreasonable” by the Naval General Staff, had occurred unimpeded. The Doolittle Raid dissolved the “residual doubts” harbored within the Naval General Staff whether or not a thrust against the important U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out the hitherto unengaged U.S. carriers, should be attempted. The Japanese army, hitherto reluctant about the enterprise, went along with the navy’s plan.

The Naval History and Heritage Command has digitized excerpts from ship deck logs pertaining to the events of 18 April 1942:

- Hornet (CV-8) deck log, 18 April 1942 [PDF, 2 MB]

- Enterprise (CV-6) deck log, 18 April 1942 [PDF, 2 MB]

- Nashville (CL-43) deck log, 18 April 1942 [PDF, 2 MB]

Also available: Nashville World War II War Diaries, 18 April 1942 excerpt [PDF, 4.8 MB]

View additional photos related to the raid.

Download an infographic summarizing aspects of the raid.

Watch footage of the event on NHHC's YouTube channel.

Sources:

Robert J. Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis, MD/Washington, DC: Naval Institute Press/Naval Historical Center, 1999.

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. IV—Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, May 1942–August 1942. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950.

Raid on Tokyo: Doolittle Report. Central Decimal Files, 1939–1942 (bulkies), box 525. Records of the United States Army, Army Air Forces. Record Group 18. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD.

Collected documents on Doolittle Raid. Central Decimal Files, 1939–1942 (bulkies), box 188. Records of the United States Army, Army Air Forces. Record Group 18. NARA, College Park, MD.

The Tokyo Raid. File 370.2, August 1, 1942 to December 31, 1942. Classified Decimal File, 1940–1942, box 525. Records of the United States Army, Army-AG. Record Group 407. NARA, College Park, MD.

Doolittle Raid. Classified Decimal File, 1940–1942, box 543. Records of the United States Army, Army-AG. Record Group 407. NARA, College Park, MD.

Aircraft Carrier Hornet (CV-8). RG24 Deck logs. October 20, 1941 to June 30, 1942. NARA, College Park, MD.

Final Reports of United States Strategic Bombing Survey. (USSBS). M1013. 1945–1947. Pacific Survey. NARA, College Park, MD.