Prelude to War

World War II began on 1 September 1939 with Germany’s invasion of Poland. The United States would not enter World War II as a combatant until 8 December 1941 with the declaration of war on Japan. On 11 December, Germany and Italy would declare war on the United States; that same day, the United States would issue a declaration of war against these two powers.

Yet how did events from the outbreak of war up to the attack on Pearl Harbor shape the operations of the U.S. Navy? What follows, while not comprehensive, focuses on the years and months before the Pearl Harbor attack on 7 December 1941.

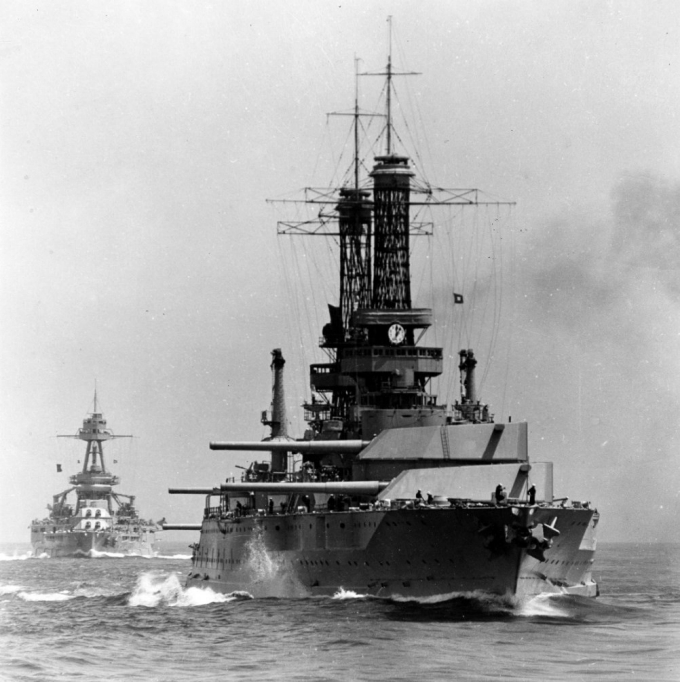

NH 73834. USS Idaho (BB-42) (foreground) and USS Texas (BB-35) steaming at the rear of the battle line during Battle Fleet practice off the California coast, circa 1930. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation, Washington, D.C. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph. Click image to download.

War Planning, 1920s–1930s

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Joint Planning Committee (the future Joint Chiefs of Staff) of the Joint Army and Navy Board developed a number of color-coded war plans to outline potential U.S. strategies for a variety of hypothetical war scenarios. War Plan Orange, with Japan as the notional foe, was the longest and most detailed. It was revised nine times between 1919 and 1938. The plan’s naval component entailed rapid offensive battle-fleet operations across the Pacific, theoretically in time to strengthen defenses centered in the Philippines. During the plan’s revisions and due to real-world developments, the American military planners finally concluded that Japan could only be defeated after a long, costly war. The plan’s final (1938) revision gave no indication of how long it should take the Navy to advance into the western Pacific and tacitly recognized the hopeless position of the American forces in the Philippines. The U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet retained the basic mission "to hold the entrance to MANILA BAY, in order to deny MANILA BAY to ORANGE [Japanese] naval forces." In this scenario, the chance of timely reinforcements was very low.

War Plan Orange, as well as the other color-coded plans, was officially withdrawn in 1939 in favor of the Rainbow Plan series. Spurred by the outbreak of war in Europe and the resulting dominant German strategic position, these plans were developed to meet the threat of a two-ocean war against multiple enemies. However, many of Orange’s planning assumptions and tenets were integrated in Rainbow 3. Rainbow 5 assumed that the United States was allied with Britain and France and provided for offensive operations by American forces in Europe and/or Africa. It was to form a basis for the U.S. “Atlantic First” strategy in World War II.

Through all of its revisions, War Plan Orange predicated naval line-of-battle operations. Even after Rainbow superseded Orange, the growing significance and potential impact of naval air and submarine operations was not fully recognized.

Rising Tensions with Japan

The U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet maintained a continuous presence in China throughout the 1920s and for most of the 1930s. One particularly active component of the Asiatic Fleet was the Yangtze Patrol, which was constituted on 5 August 1921. The Yangtze Patrol, which at its inception included one flagship and five gunboats, protected American lives, interests, and property along the Yangtze River, which served as China’s main artery. At least half of the United States’ trade with China—imports and exports—was transported via the river during this time. The Navy gunboats defended American and foreign merchant ships from river pirates who looted and occasionally fired on passing vessels. The patrol was occasionally augmented by destroyers from the Asiatic Fleet to combat raids by various bandits and communist bands.

In the 1930s, Japan sought expansion in China, and Sino-Japanese tensions increased. In July 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out. Due to the complex political-military relationship in Japan, Japanese forces in China, in particular those of the Imperial Japanese Army, operated with a great deal of tactical and operational autonomy. This situation often led to tensions and confrontations with other foreign powers, notably the United States and Britain, maintaining interests in China. Measures instituted by the Japanese included attempts to restrict navigation along the Chinese coast and in rivers, moves that were greatly at odds with the “Open Door” policy espoused by the United States. Thus, the Asiatic Fleet continued to patrol the expanding war area, if only to deter Japanese encroachment against American interests and to protect American lives. This posture led to the later officially designated first U.S. casualty in World War II—a seaman aboard USS Augusta (CA-31), the Asiatic Fleet flagship. The strained U.S. relationship with Japan was severely tested by the Japanese air attack on the river gunboat USS Panay (PR-5) on 12 December 1937, coincident with the Japanese assault on Nanking, the Chinese Nationalist capital.

In 1940, in prescient recognition of the potential threat posed by Japan to U.S. territories in the Pacific, Asiatic Fleet units were fully withdrawn from Chinese waters and concentrated in the Philippines, where they were based at Cavite and Marivales.

80-G-K-14254. USS Enterprise (CV-6) operating in the Pacific, circa late June 1941. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Click image to download.

Atlantic and Pacific Neutrality Patrols, 1939–41

Just three days after the 1 September 1939 outbreak of World War II, U.S. Navy air and surface neutrality patrols were initiated in the Atlantic. They were to continue into the final months of 1941, by which time operations had transitioned to de facto support of the Allies’ cause. Concurrently with operations in the Atlantic, much-lesser-known neutrality patrols were also carried out in the Pacific by naval air patrol assets mainly based at Cavite, Philippines, home port of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet.

Learn more:

- Navy Expansion Act, 14 June 1940

- Navy Expansion Act, 19 July 1940

- Neutrality Instructions, U.S. Navy, 1940

- The Neutrality Patrol, Part 1 (Naval Aviation News article; PDF, 1.8 MB)

- The Neutrality Patrol, Part 2 (Naval Aviation News article; PDF, 1 MB)

- The Pacific Neutrality Patrol (Naval Aviation News article; PDF, 2 MB)

NHHC accession #2007-056-01. USS Tuscaloosa. Painting by Oliver Houston. The heavy cruiser USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37) was assigned to the Neutrality Patrol initiated shortly after the outbreak of World War II. Click image to download.

U.S.-British Naval Cooperation: Scouting and Sinking Bismarck, 1941

In the summer of 1940, the collapse of Norway, the Low Countries, and France had dramatically improved Germany's position. In response to the changed strategic outlook, American policy began to shift away from neutrality. On 22 June 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a national emergency and began American efforts to control shipping in the western hemisphere. One aspect of this was the September 2 "destroyers for bases" agreement that transferred 50 aging U.S. Navy destroyers to the Royal Navy in exchange for access to British bases in North America, the Caribbean, and South America.

Learn more:

"Destroyers for Bases" Agreement

U.S. Navy Destroyers Transferred to Great Britain

The eventual close cooperation between the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy also played a role in the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck on 27 May 1941.

Learn more:

NH 69732. German battleship Bismarck, photographed 24 May 1941. Copied from the report of officers of Prinz Eugen, with identification by her gunnery officer, Paul S. Schmalenbach, 1970. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph. Click image to download.

Lend Lease Act, 1941

On 11 March 1941, Congress passed the Lend Lease Act “further to promote the defense of the United States, and for other purposes.”

Learn more:

Sources

Robert J. Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis, MD/Washington, DC: Naval Institute Press/Naval Historical Center, 1999.

Maurice Matloff and Edwin M. Snell, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare , 1941–1942. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980.

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. 1—The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939–May 1943. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948.

———, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. III—The Rising Sun in the Pacific, 1931–April 1942. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950.