USS Houston (CA-30) Memorial Service

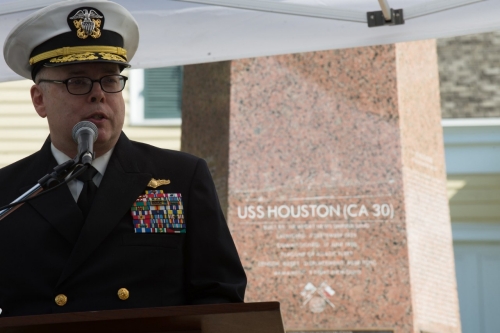

Remarks by Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, USN (Ret.)

Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, USN (Ret.), Director of Naval History, speaks at the

USS Houston (CA-30) Memorial Service held in Houston, Texas on 5 March 2016.

On a beautiful tropical night in the Sunda Strait 74 years ago (28 Feb. – 1 Mar. 1942) in what are now Indonesian waters, the commanding officer of the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth, Captain Hec Waller, and the commanding officer of the American heavy cruiser USS Houston, Captain Albert Rooks, were confronted with the most wrenching decision any warship captain can make. In the face of overwhelming odds, do you turn toward the enemy and fight, knowing that you are taking your ship and most of your crew to certain death? Or, do you go for the slim chance of escape and make a run for it?

Today the USS Houston rests on the bottom of the ocean, a little more than a hundred feet down. Her bow is facing away from the Sunda Strait, her avenue of escape, and facing toward what was then the location of the main Japanese invasion force for Java. HMAS Perth rests nearby, providing additional silent affirmation of what the survivors of the battle have always steadfastly maintained; both skippers chose to fight rather than flee. Houston and Perth were sunk while attempting to disrupt the Japanese invasion force, which is the reason they had been sent into the Java Sea in the first place, and they went down while valiantly attempting to accomplish their mission until the very end.

Their decision is all the more remarkable given what was going on around them; the collapse of the entire Allied defensive effort in the Far East in the face of a seemingly unstoppable Japanese advance. The British bastion of Singapore had fallen. Most of the Philippines had fallen and the rest would fall soon. The Allies had encountered loss after loss. Defeatism and surrender surrounded them. Both ships were low on fuel, acutely low on ammunition, and had been damaged in previous battles, the Houston severely. Their chance of escape was slim, yet both captains chose duty over survival.

The crews of the Houston and the Perth didn’t have a choice; they didn’t get a vote or a say, such is the nature of naval command at sea. The captain makes the decision, and the crew is expected to do their duty. Eighty-four days into the war, most of it in combat conditions, the crews had more than taken their measure of their captains, and their decision to fight would have come as a surprise to no one. Nor would the crews of those two ships have chosen differently had they been able to do so. And the crews of those ships performed their duty far beyond that which any nation has a right to expect.

There is no safe place on a warship in battle; the enemy shell can hit anywhere. Whether a sailor lives or dies in combat at sea is about as random an act as can be. To have any chance of success, every sailor must do his duty with maximum efficiency and effectiveness, undeterred by the possibility that at any instant an enemy torpedo or shell will blow him to eternity. Captain Rooks made the decision that he would sell his ship dearly, and that’s exactly what his crew did, inflicting extensive damage to the Japanese even while under an avalanche of fire from two Japanese heavy cruisers and numerous other escorts equally determined to accomplish their mission of protecting the Japanese troop ships. The Japanese fired almost 90 torpedoes at the Houston and Perth, any one of which could cripple a cruiser.

Perth went down first, firing until she was out of ammunition, succumbing to numerous torpedo and shell hits, Captain Waller killed on the bridge after giving the order to abandon ship. Houston fought on alone for almost another hour, damaging multiple Japanese ships while being hit repeatedly, until she too was out of ammunition. Captain Rooks was killed by a Japanese shell as he exited the bridge, after giving the order to abandon ship. As the Houston sank into the dark sea, her national colors continued to fly high in the light of star shells, and a Marine in the fighting top, probably Gunnery Sergeant Standish, who refused to abandon ship because he couldn’t swim, continued to fire his .50-cal machine gun at the enemy until the ship vanished beneath the waves.

To this day, we do not know how many American Sailors went down with the Houston, but of her crew of about 1,100 only 368 survived to be captured by the Japanese. As many as 150 are known to have made it into the water alive, only to perish from wounds, drowning, exposure, washed by the current into the vast Indian Ocean, and some were machine-gunned by the Japanese in the water. Even then, the heroism of the crew didn’t stop. As an example, a Navy legend was created when the Houston’s chaplain, Commander George Rentz, the oldest man on the ship by far, gave his life-jacket to a young wounded sailor who didn’t have one. The whole story is that every sailor that Chaplain Rentz tried to give his jacket to refused to take it. Every time he tried to push away from the sinking makeshift raft and give himself up to the sea, other sailors dragged him back. The wounded sailor who ended up with the jacket refused to put it on until well after it was clear that Chaplain Rentz had disappeared in the darkness. Such was the courage of the men of the Houston. Uncommon courage would be required even for the survivors, of whom only 291 would still be alive after three-and-a-half years of starvation, disease, torture and forced labor in brutal Japanese prisons.

We are not here today to glorify this battle; it was horror and carnage on an unimaginable scale. I think the account of one survivor, as related in James Hornefisher’s book, captured it in a way, saying, “we didn’t have a problem with sharks that night; even they were dead.” We don’t glorify this battle, because the fact that Houston and Perth were put in a no-win situation was the cumulative effect of years of bad decisions by higher political and military leaders on all sides – Allied and Japanese. Their situation was the result of what the wartime U.S. Navy Chief of Naval Operations, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, described as “a magnificent display of incredibly bad strategy.” None of it was the fault of the crew; but they paid the price. I won’t speak for Australia, but the crew of the Houston paid with their lives because this nation was not ready for war. They sacrificed their lives to buy the time needed for our nation to belatedly get ready for war.

There is no question that the war in the Pacific was a brutal fight to the death against an existential threat. But one of the most incredible, near-miraculous things that came out of that horrible war was how Japan could go from committing heinous war crimes to a peaceful, democratic nation that has proven time and again to be a great friend and ally to the United States; it is nothing less than astonishing. It leads me to two observations. One, never again must Japan and the United States face each other on opposite sides of a field of battle. And, two, this near miracle was possible because we the United States remained true to our values. We did not torture, even while being tortured. We showed our humanity and magnanimity even to a vanquished foe. The men of the Houston sacrificed their lives for these core American values.

So we are not here to glorify, but we are certainly here to honor, and most importantly, remember, what these men suffered for–those who perished, those who survived, and those who endured what we now know as post-traumatic stress. During the war, no one but the survivors in Japanese prison camps knew what happened in the Battle of the Sunda Strait. All the rest of the nation knew was that Houston did not come back from the Java Sea, nor was it known if there were any survivors. Later, Houston was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest award that can be given to a ship. Chaplain Rentz was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross, the Navy’s second highest award for valor. During the war, Captain Rooks was awarded the Medal of Honor while in missing-in-action status, for his actions in command of USS Houston during the earlier Battles of the Flores Sea and Java Sea–at that time no one knew what had happened in Sunda Strait.

Anytime the captain of a U.S. Navy ship is awarded a medal, he, or she, will invariably say that it is the crew of the ship that deserves the medal, not the captain. This is not just a trite phrase, because it is most certainly true. The captain makes the decision but it is the crew that makes it happen. Therefore, the crew of the USS Houston–and HMAS Perth who fought just as valiantly–are more than deserving of the recognition and respect given to those who have given the last full measure of devotion, above and beyond the call of duty. The least we can do as a nation is to remember them. Thank all of you who took time to be here today.