In the annals of American invention, some of the nation’s signature creations have emerged from the unlikeliest of locations and that is certainly true of the airplane, a notable example being the Wright Brothers, who built their first aircraft on the second floor of their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. After their successful demonstration of powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903, the Wrights placed their stamp on early aviation in America. One way they did so was in the construction of aircraft, many of which served as trainers for some of the first pilots in America. Among those taking to the air for the first time in a Wright machine was a young New Yorker with a keen mechanical mind that had outpaced engineering courses he took in college. In August 1912 he received certificate number 156 from the Aero Club of America, signing it with a flourish. Over the ensuing years some 15,000 aircraft and missiles would bear his name, Chance M. Vought.

The first of these appeared in the midst of the Great War and like the Wright Brothers’ early airplanes, it was born not in a hangar adjacent to a flying field, but instead on the third floor of a building in Astoria, New York, sandwiched between two businesses, one making women’s footwear and another producing phonograph records. Such was the peculiar arrangement for the Lewis and Vought Corporation that when the construction of the company’s first aircraft was completed, its components had to be lowered piece by piece through a window and assembled on the ground below. Initial engine tests took place on the street below with the tails of the planes secured to a telephone pole!

It was an inauspicious beginning for an airplane whose successors would include the fames F4U Corsair, but the VE-7 would go down in history as one of the most successful designs of its time. The first example produced was crisp in appearance, boasting polished wood surfaces and a blue trim that inspired the nickname “Bluebird.” Its performance was equally sharp, drawing praise from none other than Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell, who declared it superior to the Allied planes fighting in the skies over the Western Front. However, with these types tried and proven, the U.S. Army looked to the “Bluebird” as a trainer and placed its first order for the type in May 1918. Even with the end of World War I later that year, deliveries continued, the VE-7 gaining a measure of public notoriety when it placed first in its class in an air race between Toronto and New York in 1919 and claimed 5th place in the Pulitzer Trophy Race held in 1920.

That same year the collier Jupiter (AC 3) entered the Norfolk Navy Yard for conversion to the U.S. Navy’s first aircraft carrier and the Navy, which had relied primarily upon seaplanes and flying boats to carry out its aviation missions, now had a requirement for capable wheeled aircraft. Accordingly, the Navy placed an order for what would become a production run of 128 examples of the VE-7, half of which were produced by Lewis and Vought with the remainder built by the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia. In a testament to the soundness of the design, Navy VE-7s would be adapted to fill multiple roles. In addition to the two-seat training version, there was the type fitted with a flexible machine gun in the rear cockpit and another machine gun synchronized to fire through the forward propeller (VE-7G), a hydroplane trainer (VE-7H), and a single-seat fighter version (VE-7S). The latter was delivered in versions with flotation gear (VE-7SF) and with floats (VE-7SH).

Adapted to these configurations, the airplane was able to contribute to naval aviation afloat and ashore. On May 24, 1922, a float-equipped VE-7 with Lieutenant Andrew McFall at the controls and Lieutenant Dewitt C. Ramsey on board as an observer, zipped off the deck of the battleship Maryland (BB 45) operating off Yorktown, Virginia. A compressed air catapult enabled the plane to go from a standstill to flying speed, the event marking the first shipboard use of that type of catapult. The installation of catapults on other surface ships fulfilled a Secretary of the Navy desire that all cruisers and battleships be equipped with at least one floatplane for spotting purposes, with VE-7s initially performing these duties. Floatplane versions of the aircraft also starred in the Curtiss Marine Trophy Races of the era, the showcase for seaplanes. . On October 8, 1922, a VE-7H flown by Lieutenant Harold A. Elliott placed second in the Curtiss Marine Trophy Race. Two years later, Lieutenant L.V. Grant captured the title in the same race with an average speed of 116.1 M.P.H.

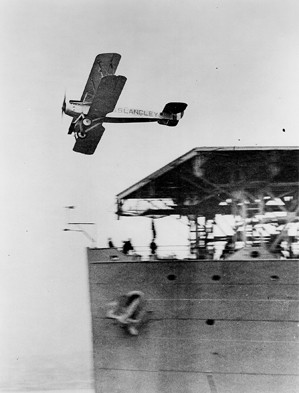

Concurrently, preparations were being made for operations on board a first-of-its-kind ship in the U.S. Navy, one in which airplanes would not be a complement to a main battery of guns, but were themselves the main battery. As yard workers completed modifications on board the former collier Jupiter that transformed her into Langley (CV 1), the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, a group of pilots were at work preparing to operate from her deck. Among them was a Lieutenant Virgil C. Griffin, a native of Alabama, who was known to his fellow officers as “Squash.” Designated Naval Aviator Number 41 in 1917, Griffin had been among the first group of naval aviation personnel to land in France following the entry of the United States into World War I. On October 17, 1922, he climbed into the cockpit of a VE-7SF poised to achieve another first, the maiden flight from Langley‘s deck. As Langley pilot Jackson R. Tate later recalled, “This was not so simple as it sounds…Since planes had no brakes, it was necessary to develop a device consisting of a bomb release attached to a wire about five feet long to allow a plane to turn up to full power and start its deck run. The bomb release was hooked to a ring on the landing gear and the end of the wire to a hold-down fitting on deck. A cord led from the bomb-release trigger to an operator on deck, who could release the plane on signal.” Griffin’s flight went off without a hitch, the Vought aircraft successfully getting airborne from the anchored Langley.

VE-7s would remain operational on board Langley into 1927, the type equipping the Navy’s early fighting plane squadrons in the 1920s. Flying from her deck, they played a role in defining the future role of carrier bases aircraft, including aerial bombing. In 1925, pilots of Fighting Squadron (VF) 2B affixed bomb racks to the undersides of their VE-7 aircraft and began practice bombing against targets laid out on the runway at Ream Field in San Diego, California. These amounted to glide bombing attacks, the VE-7 s not sturdy enough to withstand true high-angle dive bombing runs. However, these trials marked a step in the evolution of the tactic that would change the course of naval warfare during World War II battles.

The VE-7 was last reported in the Navy’s inventory in 1928, its service relatively lengthy by the standards of the interwar years, when a host of aircraft manufacturers emerged and aircraft technology proceeded at a rapid pace. As proof of the soundness of the design, elements of the VE-7 were incorporated into follow-on designs, including the VE-9 and UO.

As is the case with most of the airplanes operated by the Navy during the interwar years, no original example of a Navy Vought VE-7 survived, the 2012 arrival of a replica of the “Bluebird” completed by members of the Vought Aircraft Heritage Foundation a welcome addition to the museum’s collection. It does not take more than a brief look at it to appreciate the craftsmanship of the Golden Age honored by twenty-first century aircraft aficionados, its place in the museum a fitting for an aircraft representing the birth of carrier aviation.