Election season, particularly when it involves choosing the next occupant of the White House, brings reflections on former Presidents of the United States. John F. Kennedy’s naval legacy is well documented and his election marked the first time that a veteran of service in the United States Navy became Commander-in-Chief. Yet, it was his older brother, Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., who led the way into uniform during World War II and whose untimely death in 1944 prevented him from perhaps pursuing the political path that ultimately took his younger brother to the White House.

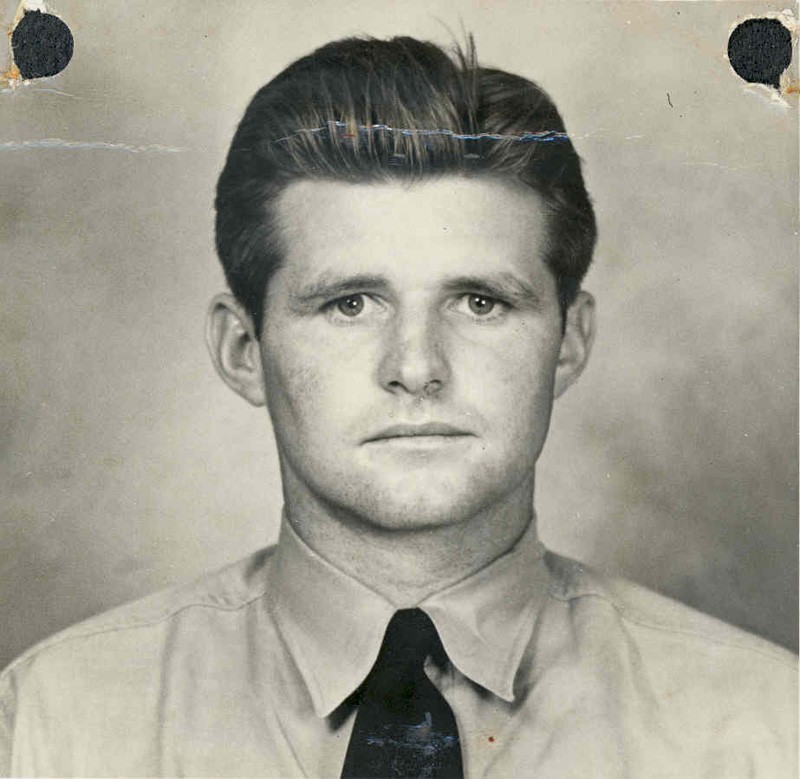

“Young Joe Kennedy After Flying Wings” proclaimed a newspaper headline in July 1941, in announcing that the oldest son of former U.S. ambassador to Great Britain Joseph P. Kennedy was reporting to Naval Air Station (NAS) Squantum, Massachusetts, to begin his flight instruction. To those who knew him, Joe Jr. possessed a seriousness of purpose and did not suffer fools, yet one of his Harvard classmates also wrote of his “thoughtfulness, ever ready smile and keen sense of humor.” In the close knit, competitive world of naval aviation, all of these attributes served him well as he completed his initial training flights at Squantum and received orders to report to NAS Jacksonville, Florida, in October 1941. Having proven his basic aptitude for flying in the skies over Massachusetts, Kennedy began an intense program of ground school and training flights upon arriving in Florida, his cadet fitness reports noting his “cheerful, cooperative disposition and…strong, forceful character…He is composed and logical in his actions in difficult situations, and he works in harmony with others.” Completing instruction in all phases of flying from instruments to flying formation to bombing and gunnery, he performed well overall despite some checkered comments from instructors, finishing 19th in a class of 70 students and receiving his wings of gold in May 1942, as American and Japanese carriers prepared to wage the Battle of the Coral Sea. Yet, with 192 hours in his log book, Ensign Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., was destined not for flying from the deck of a flattop over the blue waters of the Pacific, but instead in the cockpit of a patrol plane in the Atlantic Theater.

His initial operational flying consisted of antisubmarine patrols over the Caribbean, but in mid- 1943, he received orders to report to Bombing Squadron (VB) 110 under the command of Lieutenant Commander James R. Reedy. Transitioning to the PB4Y-1 Liberator, the Navy version of the famed B-24 flown by the Army Air Forces, Kennedy joined his squadronmates in deploying to England from which they would fly patrols over the Bay of Biscay. Operating in abysmal weather, squadron aircraft carried out around-the-clock operations searching for German U-boats, with Luftwaffe aircraft based in France frequently scrambling to intercept them. On November 9, 1943, Joe Jr.’s Liberator came under attack by Me-210 aircraft, the maneuvering of his plane into a cloud for cover likely saving his crew from the fate of squadronmate Lieutenant W.E. Grumbles, whose aircraft failed to return the previous day after radioing that he was under attack. All told, within the first six months of operations, VB-110 lost six of eighteen aircraft carrying 75 officers and enlisted men to both enemy fire and operational accidents.

In June 1944, VB-110 joined other aircraft in filling the skies over the English Channel as the Allies landed in Normandy. As the forces advanced ashore, the Eighth Air Force was developing a top secret plan to attack targets on the continent. Codenamed Project Aphrodite, the missions would involve B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 (PB4Y-1) Liberator aircraft modified with necessary control equipment and packed with explosives. These “robots,” as an official wartime report characterized them, would launch with pilots in the cockpit to fly the airplane to a predetermined altitude and bearing, at which time control would pass to a “mother ship” and they would bail out.

Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., was among the officers who volunteered for Project Aphrodite and on August 12, 1944, he and co-pilot Lieutenant Wilford J. Willy launched in an explosives-laden PB4Y-1 Liberator for a mission against Mimoyecques, France. They reached an altitude of 2,000 ft. with the “mother ships” positioned slightly behind and above the “robot.” Before reaching the first control point, the “mother ship” took control of the Liberator, using a system of on board transmitters to signal the airplane and guide it in a turn. Two minutes later, the PB4Y-1 disintegrated in an explosion, with shrapnel causing damage to a photo plane flying 300 ft. away. Kennedy and Willy were killed instantly.

The death of the twenty-nine year old Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., shook the very foundation of his family, a folder of condolence letters sent by friends, family, and complete strangers preserved to this day in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Indeed, links to his older brother would never be far from the conscience of his younger brother. In a September 1960, campaign stop in Ft. Worth, Texas, one of the people he greeted was Mrs. Edna Willy, widow of the aviator lost with his brother sixteen years earlier. Additionally, one of the ships tasked with enforcing the quarantine of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, one of the signature moments of JFK’s presidency, was the destroyer Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr.(DD 850).