On the morning of December 7, 1941, while most of the ships of the Pacific Fleet lay silently at anchor in the waters of Pearl Harbor, the carrier Enterprise (CV 6) and her escorts were underway returning to Hawaii after delivering F4F Wildcats of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211 to Wake Atoll. When they had departed on their ferrying trip ten days earlier, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. had issued Battle Order Number One to his command, noting that they were operating under war conditions given the ominous signs that international relations with Japan were deteriorating. Nevertheless, on this Sunday morning few foresaw the hostilities commencing over the horizon, including the crews of eighteen SBD Dauntless dive-bombers as they prepared to launch to search ahead of the carrier and then land at Ford Island. If anything, they were going to have the opportunity to go ashore before their shipmates arrived in port.

Among those manning his aircraft was Ensign Walter Willis, a Minnesotan who served a tour in the Marine Corps before joining the Navy and entering flight training. Considered one of the best aviators in the squadron despite his junior rank, Willis had written regular letters to his mother during 1940–1941, copies of which are part of a collection of materials donated to the museum by family members.

“We are still throwing miniature bombs all over the countryside and scaring h__l out of fishermen while we’re machine gunning,” he wrote from San Diego on November 18, 1940. “I am now a qualified ‘carrier pilot,’ having checked out on theSaratoga with seven take offs and landings aboard her—solo. Wasn’t bad at all, in fact, a lot of fun.” On one cross-country flight, he wrote of landing in a field and almost getting stuck in six inches of loose sand that covered it. There would have been worse places to await assistance, the site of the field being the winter resort town of Palm Springs, where he noted that he “met [actor] Charles Farrell and saw B. Crosby’s wife [Dixie Lee] playing tennis.”

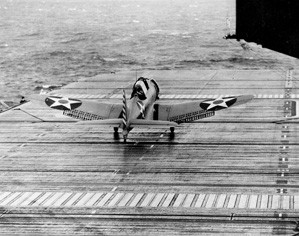

The following April, Willis wrote about the arrival of new airplanes in his squadron, Scouting Squadron (VS) 6. “Got our new ships in commission and they certainly are sweet. Up high they move like a cat that has sat in a puddle of turpentine.” The plane did not treat him so well during one at sea period on board Enterprise. “This crack-up you’ve heard rumors about wasn’t even worth mentioning,” he wrote on November 16, 1941. “All that happened was my engine failed on a take-off from the carrier and I plopped into the ocean about a half mile in front of the ship. I was only wet up to my knees and got that while I was standing on the wing reading the instructions on ‘how to operate’ the inflatable life raft.” He also wrote of his assigned airplane, side number 6-S-15. “She’s my own while at sea and my pride and joy.”

As the Enterprise planes approached Hawaii, they saw air activity that was unusual for a Sunday morning, with some of them quickly coming to the realization that the enemy was in the sky as Zero fighters made gunnery runs on them. To add to the danger, as some of the planes attempted to land, they were forced to do so amid friendly antiaircraft fire. Making their approach to Ford Island, Willis and his wingman, Lieutenant (junior grade) Frank A. Patriarca, noticed smoke rising from Pearl Harbor and altered their course to one that took them along the southern coast of Oahu.

Suddenly, the two planes were attacked by Zero fighters, which made firing passes at them from above and behind. In the rear seat of Patriarca’s aircraft sat Radioman First Class Joseph F. DeLuca. An experienced gunner, he managed to un-house his .30 caliber machine gun. In Willis’ aircraft was the squadron master-at-arms, Coxswain Fred Ducolon, who had no such experience and was primarily a passenger expecting an uneventful flight. As the Japanese planes attacked, Patriarca put his Dauntless into a steep dive and eventually shook his pursuers. He never saw Willis and his aircraft, “his pride and joy,” again.

All told, of the eighteen Dauntless dive-bombers that launched that fateful morning, one was shot down by friendly fire and five others fell to Japanese aircraft. Not until December 22nd would a telegram arrive at 140 8th Avenue NE in Minneapolis informing Mrs. Marie Willis that her son was missing in action. Four days later a personal letter from Rear Admiral John H. Towers arrived, this one bearing news that her son’s status had been changed to killed in action.

The name Willis would carry on in the war that claimed his life. On December 10, 1943, the destroyer escort Willis (DE 395) was placed in commission in Houston, Texas. Ironically, its combat actions came not against the Japanese, but the Germans, serving in antisubmarine task groups centered on the escort carrier Bogue (CVE 9), one of the most successful ships of her type in sinking German U-boats. After Germany’s surrender, Willis was transferred to the Pacific Theater, arriving at Pearl Harbor on August 7, 1945, forty-four months to the day after her namesake flew into the midst of the first shots of America’s second world war.