He looked professorial in his appearance with his tailored suit and pince nez, much different from the familiar figure in the White House during the Great Depression and Second World War. The tall, slender 31-year old assistant secretary of the navy had been in office exactly 8 months when he arrived in Pensacola, Florida, on November 17, 1913, to inspect the navy facilities there. Just over two weeks after Franklin D. Roosevelt departed, a transport carrying 800 Marines moored at the navy yard, which though officially closed since 1911, was beginning to show signs of life. The leathernecks, under the command of a future Marine Corps commandant, Colonel John A. Lejeune, set up quarters in the stoic brick buildings on the navy yard. The movements seemed to portend its reopening given its proximity to Mexico, a country whose diplomatic relations with the United States were deteriorating.

Yet, Pensacola’s future lay with something outside observers, including the city fathers, could not have imagined. While Roosevelt visited and Marines landed, a document was making its way through the Navy Department bureaucracy, its words representing the findings of the Chambers Board, a group of officers led by Captain Washington Irving Chambers that was tasked with charting a course for the future development of aviation in the Navy. Among its chief recommendations was the establishment of an aeronautic center at which to concentrate the sea service’s aviation activities.

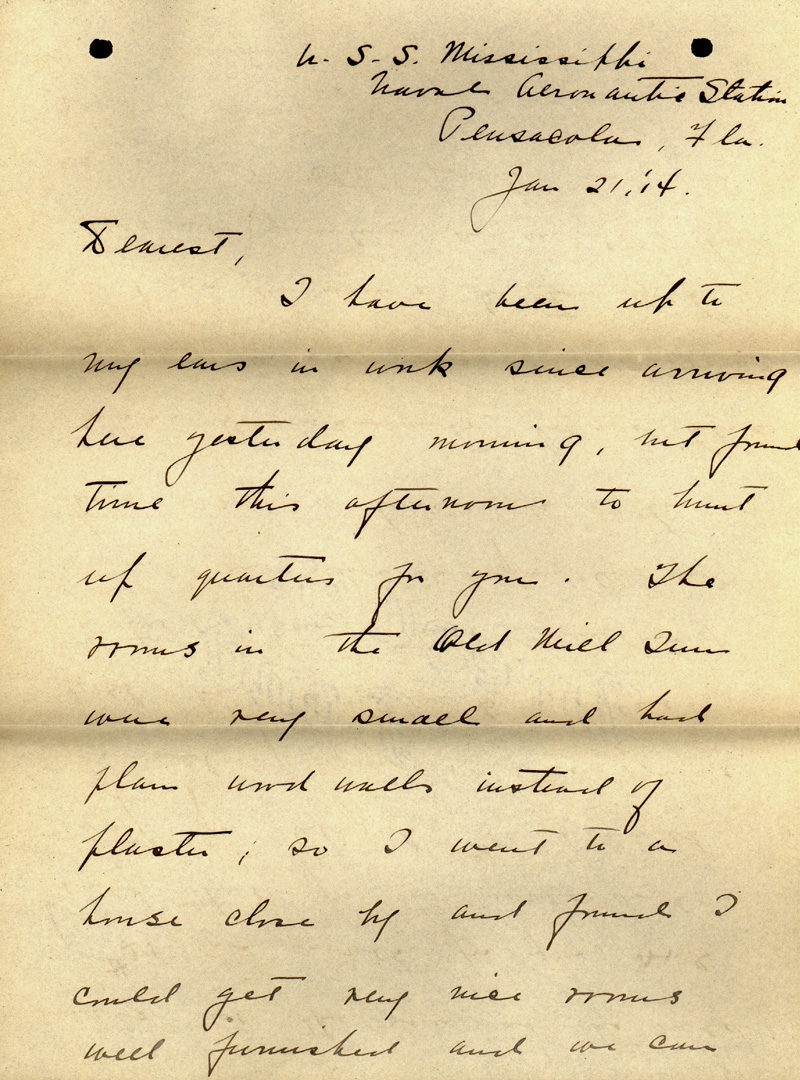

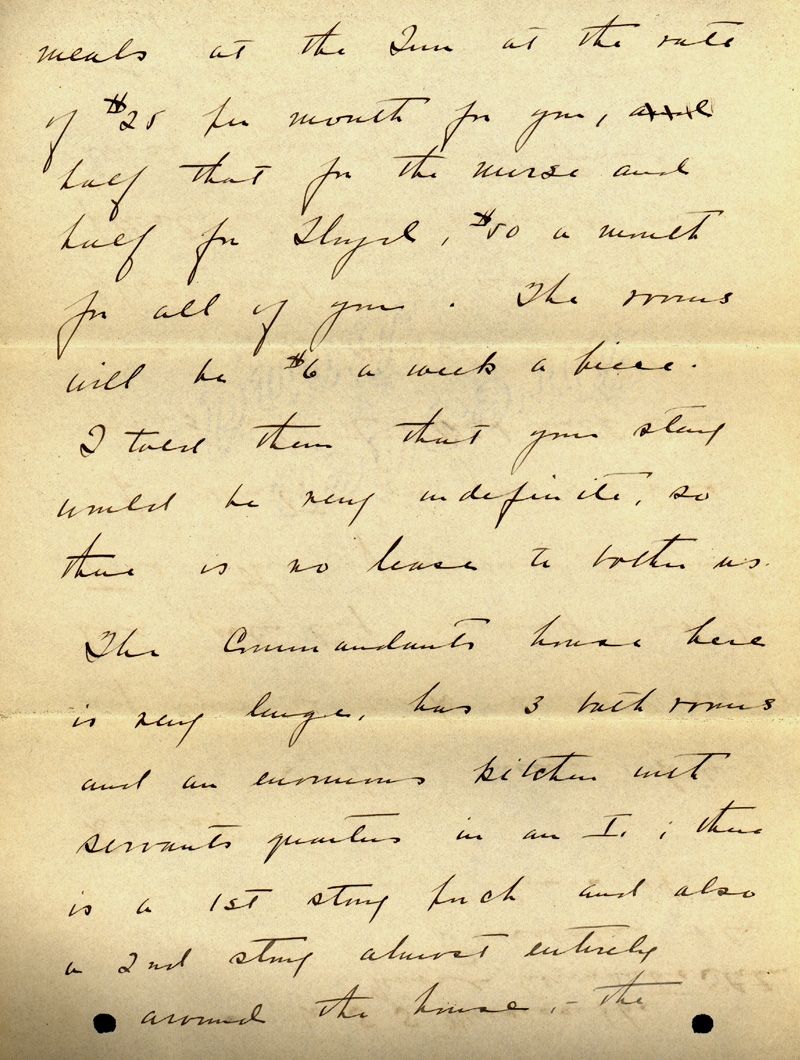

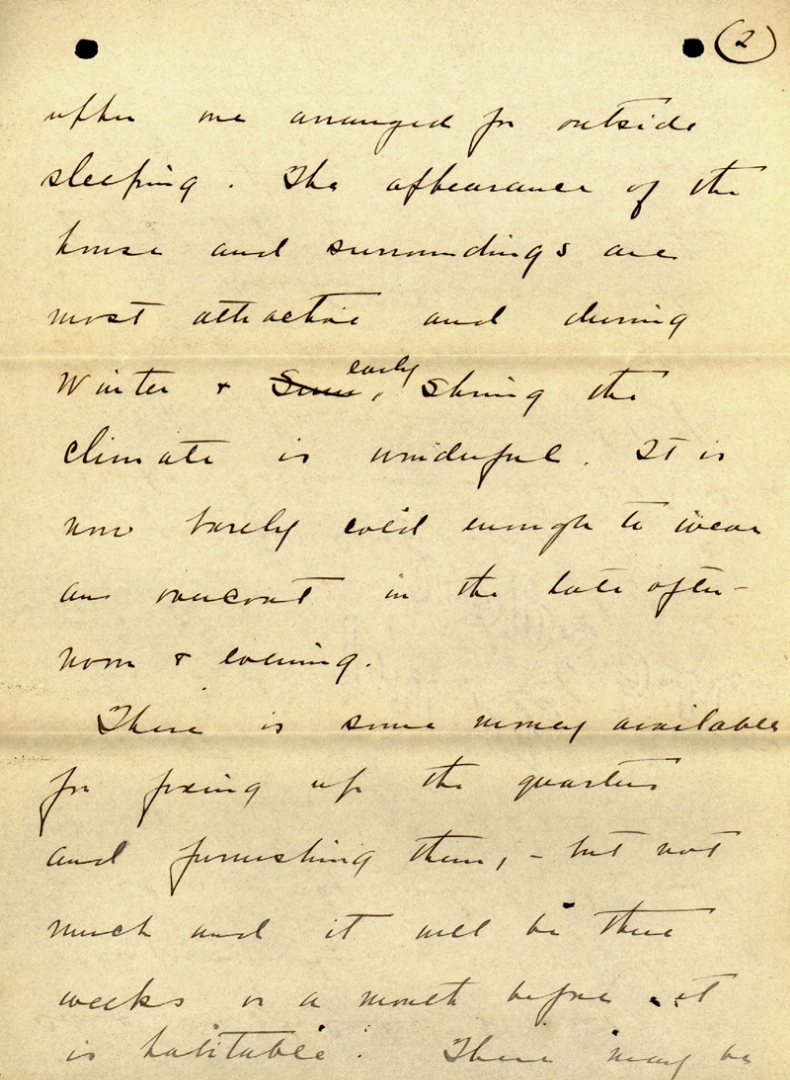

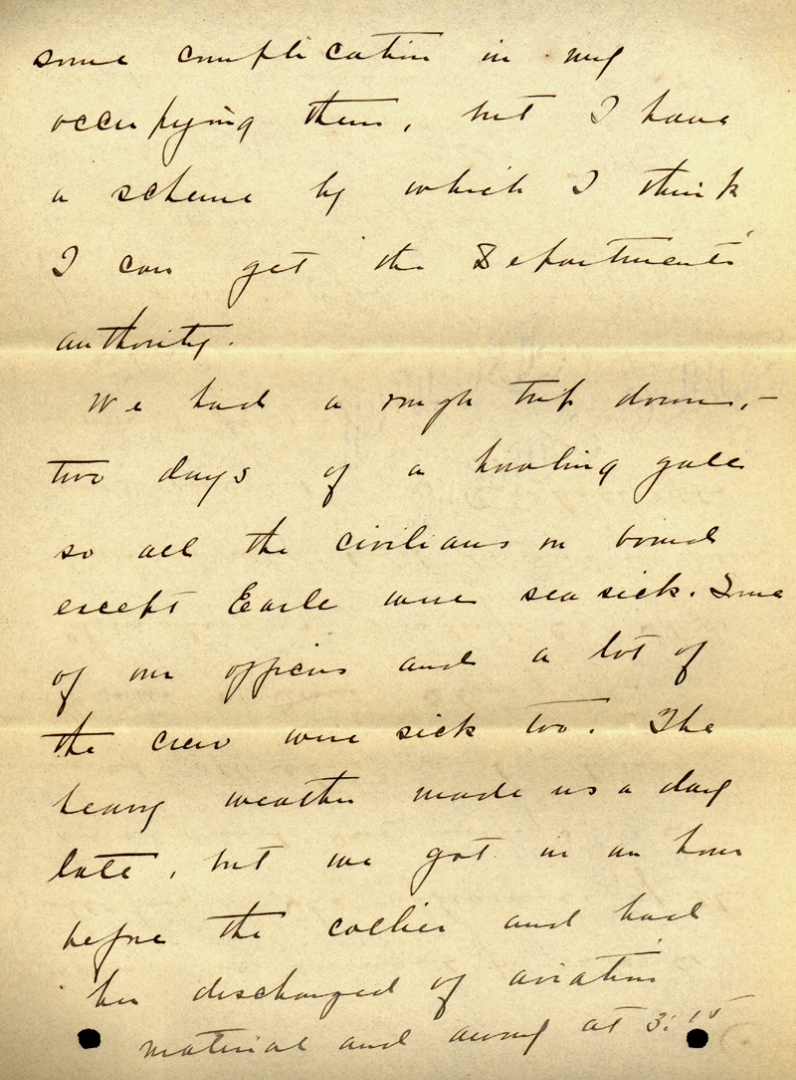

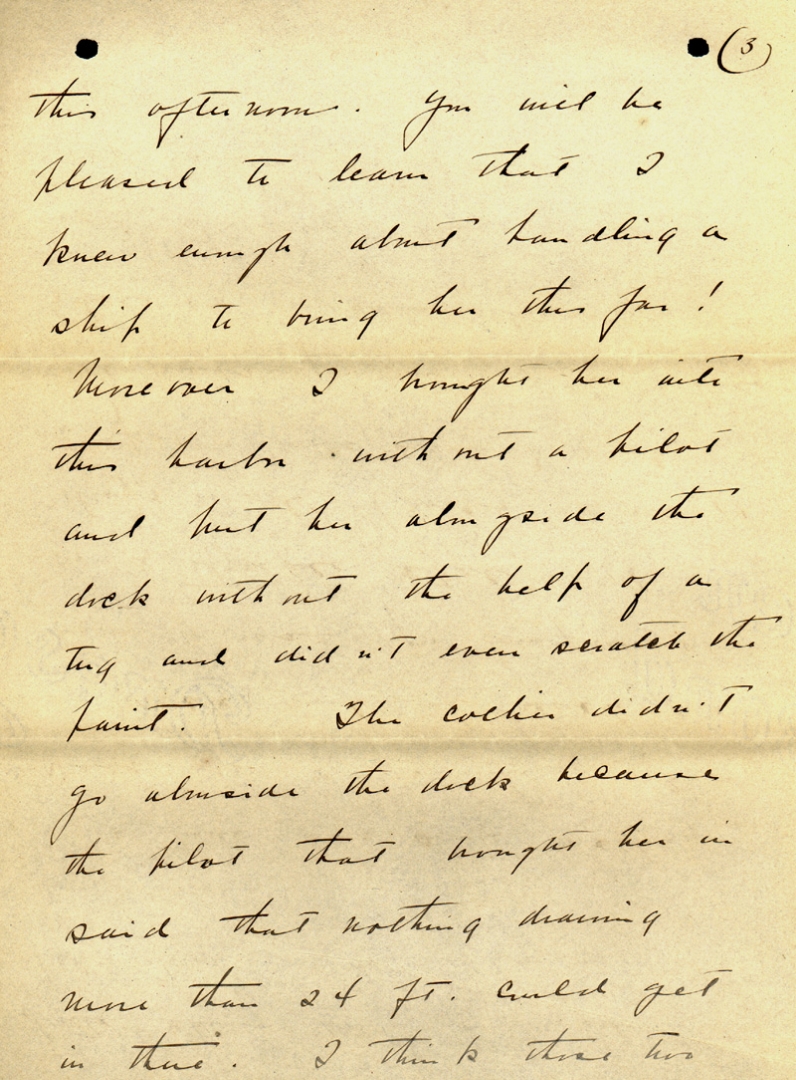

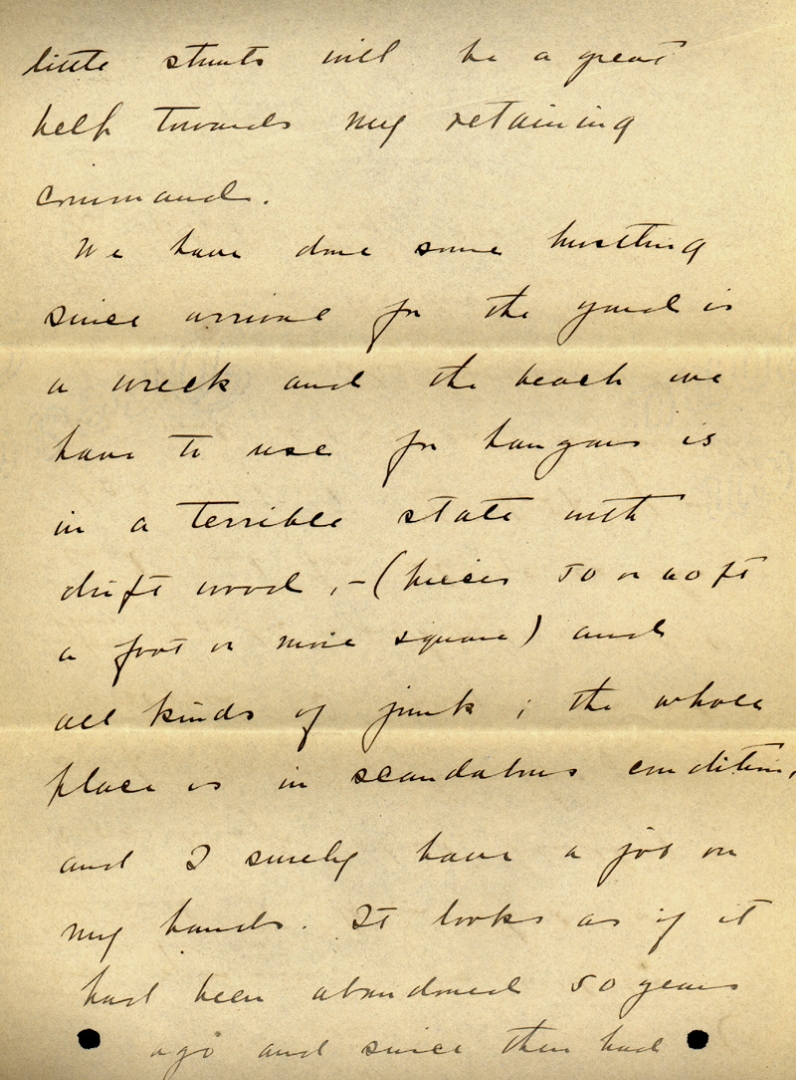

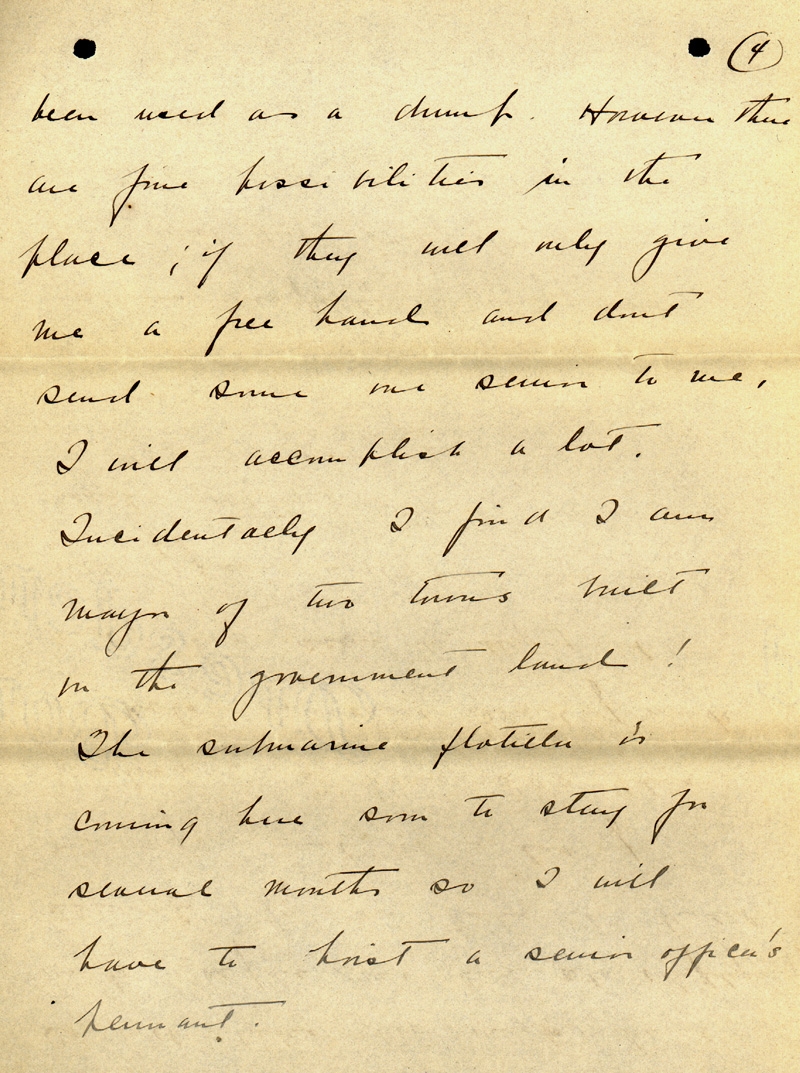

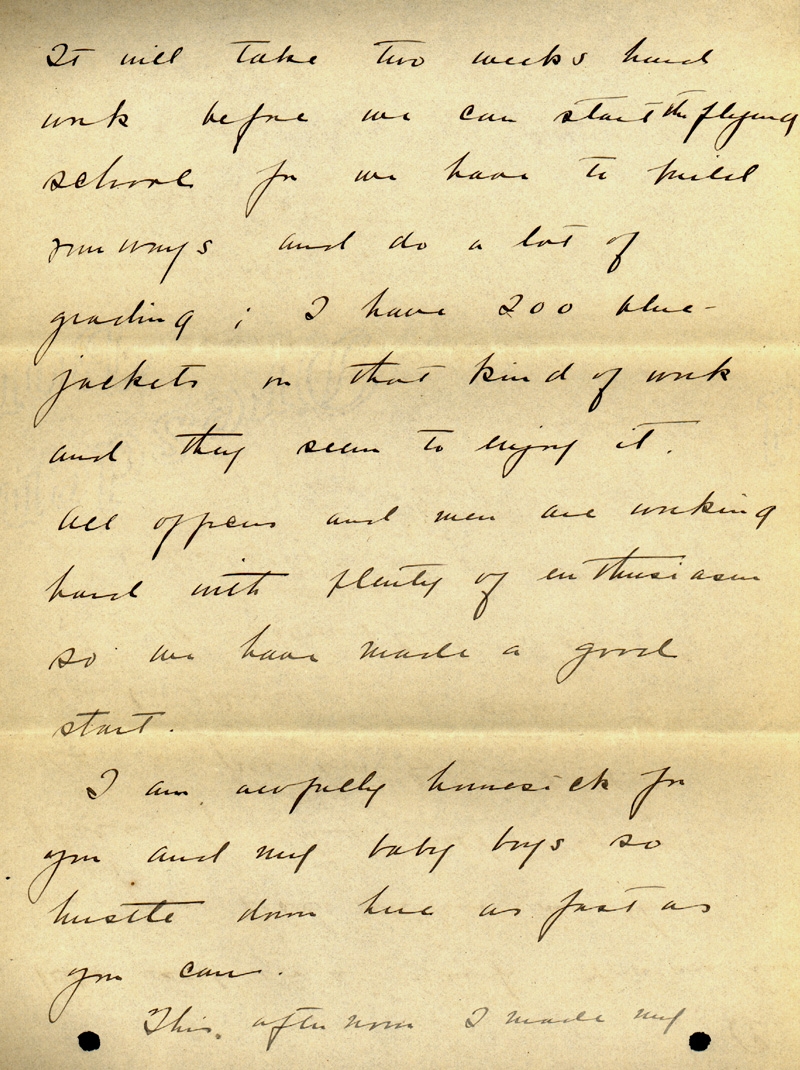

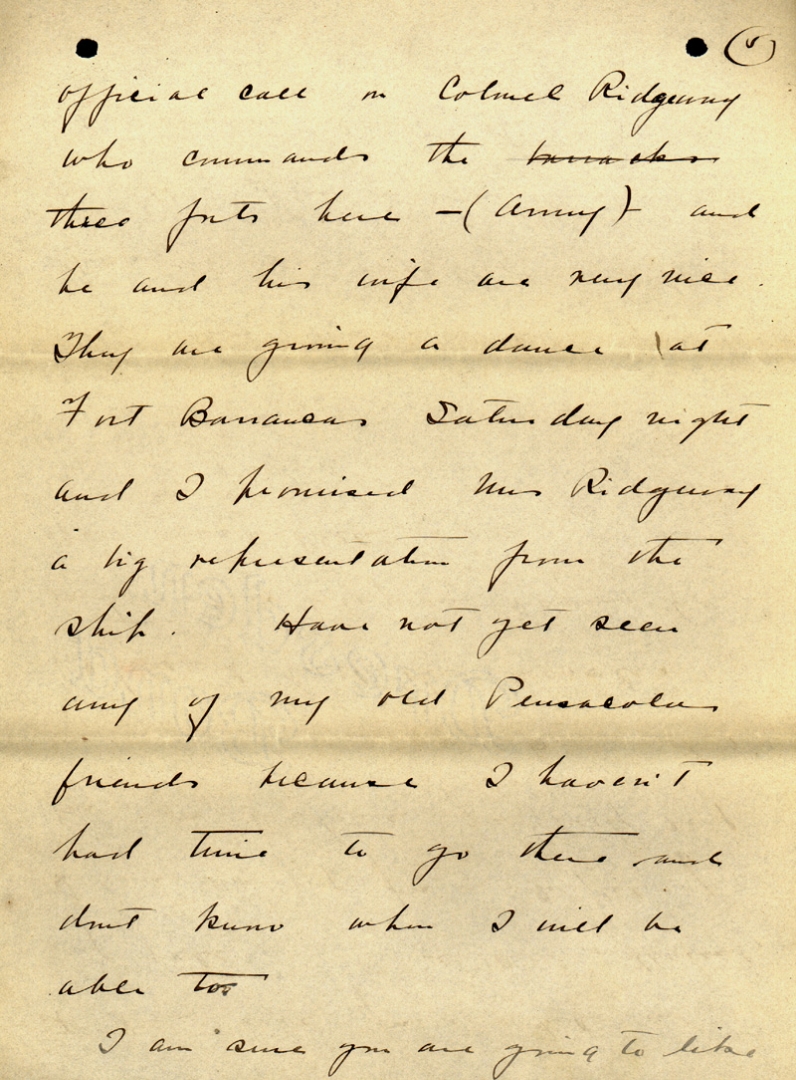

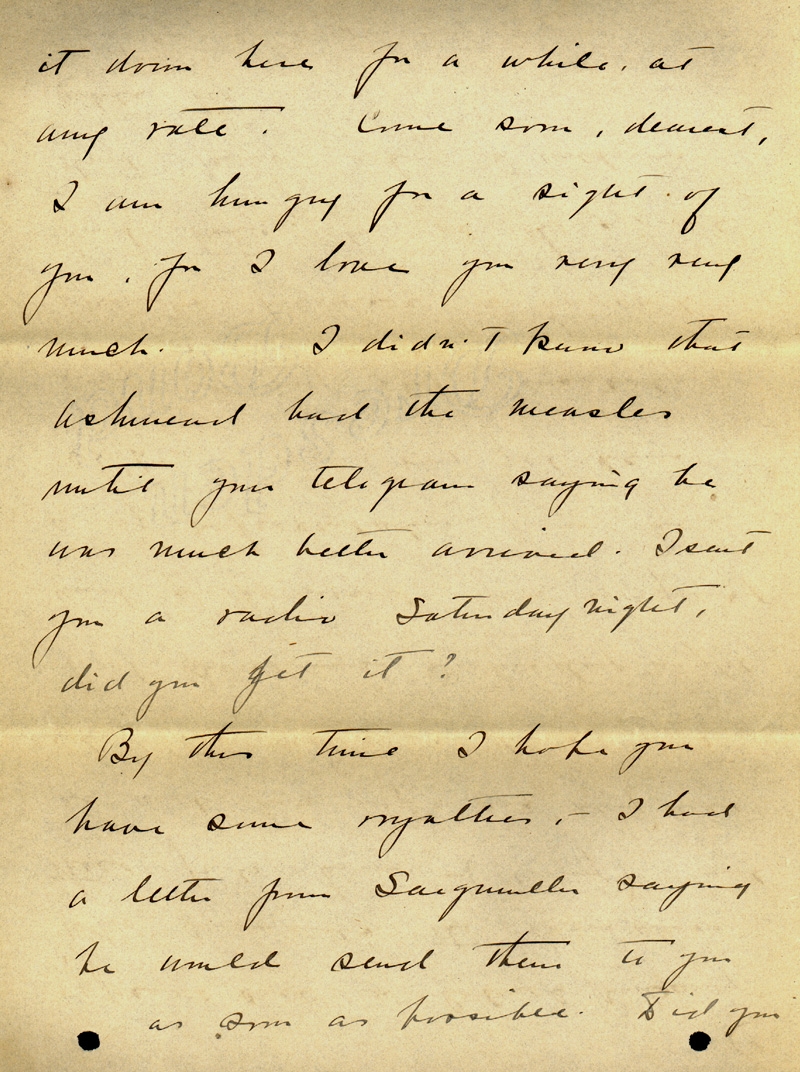

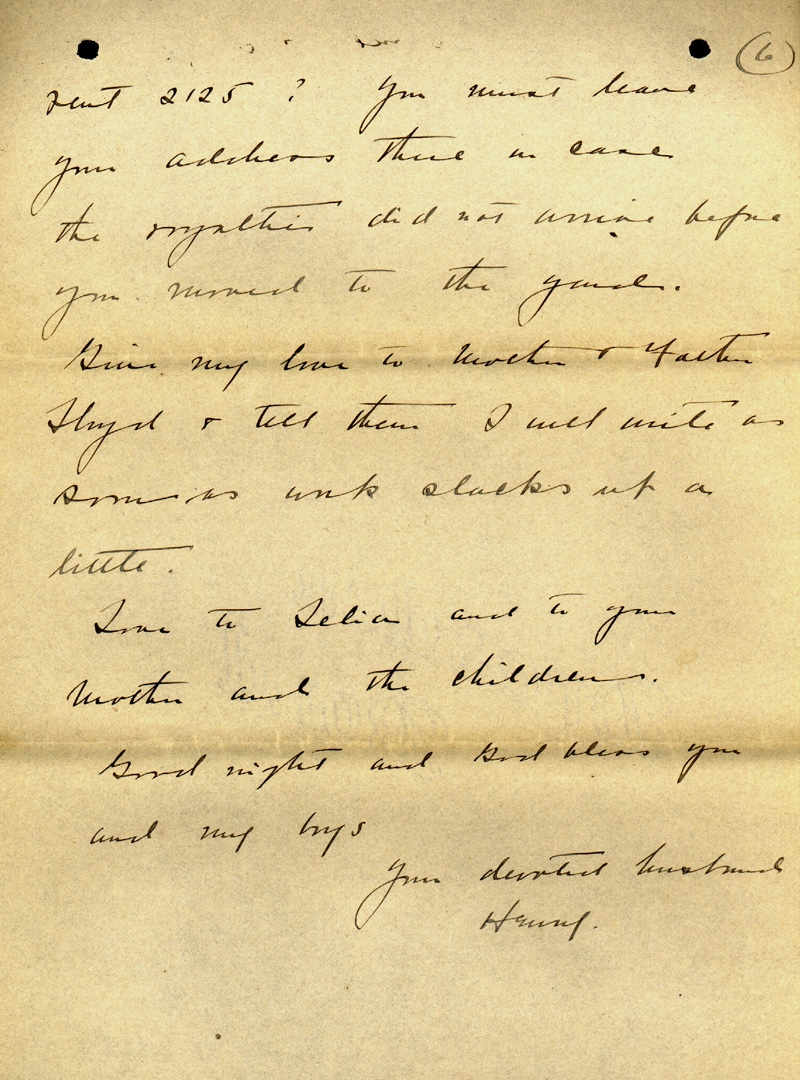

The approval of that recommendation led to the morning January 20, 1914, when two ships, the battleship Mississippi (BB 23) and collier Orion, made their way through Pensacola Pass past the brick walls of Fort Pickens towards the navy yard. On board was the entire naval aviation establishment, which at the time was an unimpressive assortment of wood and fabric biplanes flown and serviced by a handful of officers and enlisted men under the command of Lieutenant John Towers, the Navy’s third aviator. Tasked with establishing the station itself was Lieutenant Commander Henry Mustin, commanding officer of Mississippi, who recorded his first impressions of the navy yard in a letter to his wife. “We have done some hustling since arrival for the yard is a wreck and the beach we have to use for hangars [full of] drift wood…and all kinds of junk; the whole place is in scandalous condition, and I surely have a job on my hands. It looks as if it had been abandoned 50 years ago and since then had been used as a dump. However, there are fine possibilities in the place.”

It would take time for the possibilities to become realities, the logistical challenges of all that went into establishing a shore command taking months to overcome. In the meantime, the aviation personnel lived aboard the battleship and worked in canvas tent hangars erected along the shore Pensacola Bay. It was from that shore on February 2, 1914, that Towers and Ensign Godfrey DeC. Chevalier took to the skies in two of the recently assembled aircraft, which the Pensacola Journal likened to “giant buzzards.” They marked the first of hundreds of thousands of flights launched from what would become known as the “Cradle of Naval Aviation.”