Naval Air Station (NAS) North Island, California, proclaims itself the “Birthplace of Naval Aviation” owing to the fact that Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson, Naval Aviator Number 1, received his initial training there. As the Navy’s first air station, NAS Pensacola, Florida, is known as the “Cradle of Naval Aviation.” These two historic installations have endured and stand as hallmarks of naval aviation’s heritage. Between them in history is a location that was naval aviation’s first base, albeit a temporary one, its story beginning on July 6, 1911, when Captain Washington Irving Chambers was ordered to report to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, for the purpose of establishing it.

Indeed, in the months after the Navy assigned its first officers to aviation duty and contracted for its first aircraft, naval aviation led a vagabond existence. Training was carried out at locations at which aircraft manufacturers of the day operated, North Island and Hammondsport, New York, in the case of Glenn Curtiss and Dayton, Ohio, in the case of the Wright brothers. In an effort to provide some degree of centralization for aviation, the decision was made to locate operations for part of the year at Greenbury Point located across the Severn River from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The site was also the location of the Engineering Experiment Station, which was beneficial to aviation’s advancement because of the support that it could provide, particularly with respect to aircraft engines. Proximity to the Washington Navy Yard was also deemed an attribute to establishing an experimental station at Greenbury Point, particularly because that was the site of the development of early floats for seaplanes.

It was not until September 1911, that Lieutenants Ellyson, John Rodgers, and John Towers, reported to the Superintendent of the Naval Academy for “duty…in connection with the test of gasoline engines and other experimental work in the development of aviation.” While the men were graduates of the institution, they did not receive a warm welcome at their alma mater, officers there having little use for aviation and no administrative process for procurement of parts and other material. Access to Greenbury Point was by way of a boat that the aviators soon found to have a most temperamental engine.

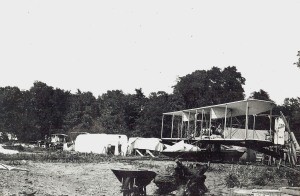

In contrast to when naval aviation shifted operations to Pensacola three years later, the camp at Greenbury Point included a field for landplane operations and a building that served as a hangar. However, the location was in proximity to the midshipmen rifle range, stray shots occasionally holing the aircraft and the firing practice schedule necessitating the cessation of operations on certain days of the week. Because of this, as well as placement of an emphasis on hydroaeroplane operations, Greenbury Point also included tent hangars placed along the river’s edge.

Operational for less than three years, Greenbury Point was nevertheless a part of some of the notable events of naval aviation’s pioneer days. Early testing of airborne wireless radio transmission occurred in flights from the location, which was also the jumping off point for what in that era passed as a long-distance flight of 122 miles to Fort Monroe, Virginia. Aircraft also performed experiments in spotting submerged submarines in the Chesapeake Bay, while on the ground testing was performed on types of wire to determines which would be more structurally sound in aircraft construction. Lieutenant John H. Towers established an endurance record in the skies over Greenbury Point, remaining aloft for over six hours on October 6, 1912, an impressive stretch given that there was n enclosed cockpit in the A-2 he flew.

Greenbury Point also served as the location for a shift in aviation training, with the initial cadre of naval aviators trained by the manufacturers of the Navy’s first aircraft carrying out the duties of training other officers. The first to report for this duty, Ensign Victor D. Herbster, arrived at Greenbury Point in November 1911, and he was followed by First Lieutenant Alfred Cunningham, the first Marine Corps officer to report for flight training. Others included Godfrey DeC. Chevalier, who eventually became the first to land an aircraft on board a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, and Patrick N.L. Bellinger, who in 1914 flew the maiden combat missions in U.S. military history. Ensign William D. Billingsley also made training flights from Greenbury Point, one of them on June 20, 1913, ending in tragedy when the Wright B-2 he was flying along with Lieutenant John H. Towers went out of control and plunged into the Chesapeake Bay. Billingsley was thrown from the aircraft and fell to his death, naval aviation’s first fatality.

By late 1913, the Navy had convened the Chambers Board to review aviation policy, one of its tasks to find a permanent home for naval aviation. The members settled on the recently closed Pensacola Navy Yard. This signaled the end of flights at Greenbury Point, which nevertheless symbolized a short-lived, but important chapter in the development of naval aviation.