For the millions of people mobilized for service in aviation during World War II, a sound that pervaded their daily existence was the roar of piston-engine aircraft, whether it be the great bomber fleets over Europe or fighter planes launching from carrier decks. Yet, even while these planes waged war, engineers around the world were at work on the next generation of airplane, one that would bring manmade thunder to the sky.

For the U.S. Navy, the effort to obtain a jet aircraft began in 1942, when the Bureau of Aeronautics began seeking out a manufacturing candidate for what was hoped to be an airplane that would transform naval aviation. Just months removed from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the nation was mobilizing for war, the established manufacturers like Grumman, Curtiss-Wright, and Vought on which the Navy had traditionally relied for carrier aircraft focused on mass production of more tried and true designs. To this end, the Navy turned to a relatively new addition to the nation’s aeronautics industry, the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, incorporated in 1939 and founded by Princeton-educated former Army Air Service pilot James Smith McDonnell. The company was not afraid to pursue the unconventional, its first military design the XP-67, a twin-engine fighter in which engineers attempted to harness the engine exhaust to improve thrust and therefore increase speed. On January 7, 1943, the Navy issued a Letter of Intent for what would eventually become the FD-1 (later redesignated FH-1) Phantom, naval aviation’s first jet fighter.

Just over three years later on January 26, 1945, the prototype made its maiden flight, the era of jet aircraft in combat having begun half a world away the previous August when the first German Messerschmitt 262s began flying combat missions over Europe. Placed in production, the FH-1 Phantom in final form featured a pair of 1,600-lb. static thrust Westinghouse engines that gave it a top speed of 479 m.p.h., a 68 m.p.h. increase over the most advanced propeller fighter design of the time, Grumman’s F8F Bearcat. Though the initial order was for 100 planes, the end of World War II prompted a reduction of the production run to 60 aircraft.

Though the Phantom successfully completed carrier trials with landings on board the carrier Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVB 42) in July 1946, not until a full squadron was equipped with the aircraft and carrier qualified could naval aviation claim that the jet had indeed gone to sea. The squadron to which this honor fell began life during World War II as Fighting Squadron (VF) 82, and been redesignated VF-17A in November 1946. Based at Naval Air Station (NAS) Quonset Point, Rhode Island, squadron members first got wind that something new was in the air on July 1947, when a request was made to send four pilots to Naval Air Test Center (NATC) Patuxent River, Maryland, for indoctrination in jet aircraft. The first Phantoms arrived the following month, and were a novelty for the entire station. “Talk about your three ring circus—every time a jet turns up prior to a flight, it seems to be the signal for everyone within hearing distance to come a runnin’ and watch the show,” recorded the official squadron history.

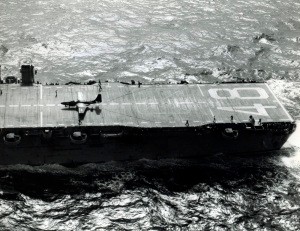

Over the course of the ensuing months VF-17A filled its ranks with more experienced pilots, the baseline being men with at least 1,000 hours of flight time and 50 carrier landings. In addition, a new skipper reported aboard, a “mild spoken, but forceful, gentleman” named Commander Ralph Fuoss, whose previous assignment was command of Carrier Air Group (CVG) 5. They would need to muster all of that experience for the task ahead, which became all too real on May 1, 1948, when 16 FH-1 Phantoms were hoisted on board the light carrier Saipan (CVL 48) at NAS Quonset Point. “The acid test for practical jet carrier operation was at hand.”

The ship put to sea in the Atlantic two days later, and over the course of the ensuing days the pilots of VF-17A practiced launches and recoveries and flew intercepts against P2V Neptune patrol planes. All told, they logged 200 landings with only a minor mishap, with every squadron pilot carrier qualifying with a minimum of 8 landings. Thus, on May 5th, the squadron had the distinction of being the first carrier qualified jet squadron in the history of the U.S. Navy, a press releases noting that the cruise “removes carrier jet operations from the realm of newsworthy experiments and displays them in their true light in a fully organized and trained squadron taking its place as a weapon in the Navy’s Air Arm.”