While June 1944, is most remembered for the events that happened in Normandy, the month also marked the launching of another pivotal D-Day in the Mariana Islands, the inner ring of the island strongholds defending Japan. As expected, the Imperial Japanese Navy contested the invasion of the Marianas, confronting the U.S. Navy in what became known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea on June 19-20, 1944. The first day included massive air attacks against U.S. Navy carriers, during which the Japanese lost scores of planes to defending F6F Hellcat fighters, prompting one aviator to liken the air-to-air combat to an “old-fashioned turkey shoot.” The following day, U.S. carriers were released from covering the beachheads to pursue the enemy fleet from which the planes had been launched the previous day, getting into position to launch strikes at extreme range late in the afternoon of June 20th.

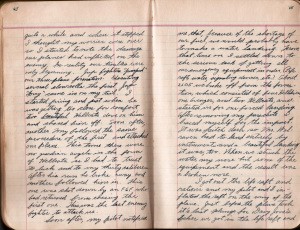

Among those taking to the air was Aviation Radioman Second Class John Conrad Bramer, Jr., of Bombing Squadron (VB) 14 on board the carrier Wasp (CV 18), whose diary captured what turned out to be a lengthy mission. Bramer and his pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) Albert Walraven, left Wasp’s deck at 1630. Arriving over the enemy, Walraven picked his target and initiated his dive bombing run.

“Then the fireworks started. More anti-aircraft fire came up at us from those ships below than I ever had the misfortune to dodge up until that time,” Bramer wrote. After dropping his bomb on an oiler, Walraven exited the area. “The ‘ack-ack’ followed us for quite a while and when it stopped I thought my worries were over. In reality our troubles were only beginning.” Fighters of the Japanese combat air patrol descended on the SB2C, prompting evasive action by Walraven as Bramer fired his .30-caliber machine guns at the enemy planes. Fortunately, F6F Hellcats that had escorted the strike group arrived on the scene, driving off the Japanese fighters.

Launched at the limits of their combat range, the crews that took off from U.S. carriers that day understood that many would not be able to make it back to their ships. The maneuvering to avoid the attacking Japanese aircraft took its toll on Welraven and Bramer’s fuel supply, and “about 2105 we broke off from the formation, and started in for our forced landing. After removing my parachute I braced myself for the impact. It was pitch dark so Mr. Walraven had to land entirely by instruments and a beautiful landing it was.” Nevertheless, the jolt of hitting the water sent Bramer’s face crashing into some equipment around him, breaking his nose.

Inflating their life raft and climbing aboard, the two men awaited the dawn and hoped for rescue. Daylight soon brought the sight of an aircraft on the horizon, the use of a signal mirror and flare prompting its pilot to fly over the raft and drop a dye marker. After a time more aircraft appeared, the sight of one of them peeling off as if to begin a strafing run prompting the downed fliers to jump overboard. Thankfully, the aircraft were F6F Hellcats, which circled over the raft for a time until relieved by another pair of fighter planes. In short order, a mast appeared on the horizon, the two men in the raft welcoming the sight of the submarine Seawolf (SS 197).

The pair remained aboard until Seawolf returned to her base at Midway Atoll, from which they were transported back to Wasp. “After two weeks of traveling by boat, car, jeep, ship, and airplane,” Bremer concluded, “we finally reached our ship and it certainly was swell to get back.”