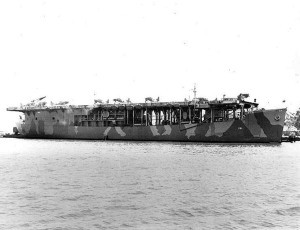

Aircraft filled every available space in the small confines of the auxiliary aircraft carrier Long Island (ACV 1) as she steamed towards the island of Guadalcanal, where just two weeks earlier leathernecks of the First Marine Division had gone ashore in the first Allied offensive of the Pacific War. Pushing through the jungle landscape, the Marines seized the airfield that had been under construction by the Japanese, the threat of severing the lines of communication with Australia by enemy aircraft flying from Guadalcanal being one of the primary reasons for the invasion. Meanwhile, in waters off the island that would eventually become known as “Ironbottom Sound,” the U.S. Navy had suffered devastating defeats in surface engagements with the Imperial Japanese Navy, which reduced naval support for the Marines on shore. Thus, Henderson Field, named in honor of a Marine aviator killed at the Battle of Midway, became their key lifeline, a fact known to the Japanese as they tried everything in their arsenal to seize it.

The aircraft on board Long Island represented the first Marine aviation assets committed to Guadalcanal, the beginning of the “Cactus Air Force,” so named after the Allied codename for the embattled island. On August 20, 1942, thirty-one aircraft that were part of Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 23 catapulted off the tiny carrier’s deck and set course for Guadalcanal. The planes included nineteen F4F-4 Wildcat fighters of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 223 and twelve SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bombers of Marine Scout Bombing Squadron (VMSB) 232. What awaited them was a far cry from life aboard ship. Just a day after their arrival, forces under the command of Kiyonai Ichiki launched an attack against the Marines in what became known as the Battle of the Tenaru River.

Over the course of the ensuing weeks, an assortment of aircraft arrived, including Army Air Forces P-400 Airacobras and B-17 Flying Fortresses as well as Navy carrier aircraft from flattops damaged in carrier battles with the Japanese. For the airmen on Guadalcanal, the pattern of existence was defined by the horrific conditions and enemy movements on land, in the air, and upon the sea. The first battle was against the island itself, a steamy jungle landscape that spawned disease and bore the ever-present stench of rotting vegetation. The airfield was under constant threat of attack, either by ground forces, air raids by Japanese planes flying from Rabaul, or bombardments by enemy surface ships, the vessels that staged these night attacks dubbed the “Tokyo Express.” Recalled the skipper of VMSB-232, Lieutenant Colonel Richard C. Mangrum, “The pressure on Guadalcanal was constantly increasing and the tempo of daily air raids and nightly shelling from the sea began to be very wearing on the nerves of everyone…Rest became a practically unknown factor.”

In the air, the pilots and aircrewmen proved vital to the campaign to take Guadalcanal. They provided close air support for Marines on the front lines and scouted for Japanese ships approaching the island, the devastating attacks delivered against them stemming the flow of reinforcements and supplies bound for the Japanese garrison on Guadalcanal. When Japanese bombers and Zero fighters approached, Wildcat pilots roared aloft, the roster of Marine fighter pilots shooting down enemy planes in spades including Medal of Honor recipients Joe Foss, Robert Galer, Harold Bauer, and John Smith as well as legendary Marine aviators Marion Carl and Paul Fontana. In one of the more storied missions flown from Henderson Field, Marine Major Jack Cram delivered a torpedo attack against Japanese shipping while flying a PBY Catalina assigned as the personal plane of Brigadier General Roy S. Geiger!

A testament to the hardships endured by those flying from Guadalcanal is the report of the MAG-23 medical officer on the status of VMSB-232 pilots after five weeks of combat. Seven had been killed in action, three others were wounded, and two had been evacuated due to extreme mental and physical fatigue. Only three remained unscathed, though they required prolonged rest due to their mental and physical states.

Following their defeat in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942, the Japanese made no further attempt to reinforce the island, which was officially declared secure in February 1943. Henderson Field and other airstrips built around it continued to serve as a base supporting further operations in the South Pacific, all aircraft that flew from Guadalcanal carrying on the legacy of the “Cactus Air Force” that began operating in August 1942.