Over the course of the previous decade, the flight decks of the aircraft carriers Hancock (CVA 19) and Midway (CVA 41) had witnessed thousands of launches of bomb-laden aircraft heading towards enemy targets in North Vietnam. However, as the war-weary flattops steamed in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin on April 29, 1975, a steady stream of helicopters dotted the airspace over them and other Seventh Fleet ships, the aircraft carrying U.S. government officials and those South Vietnamese nationals fortunate enough the escape the North Vietnamese military forces pushing into the streets of the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon.

In previous days, aircraft flying from Tan Son Nhut airbase near Saigon had maintained a steady schedule of evacuation flights, but as North Vietnamese troops began lobbing artillery rounds onto the airfield, this lifeline was cut. Thus, President Gerald R. Ford initiated a helicopter airlift from the sea, its codename Operation Frequent Wind. In short order, a fleet of some 80 helicopters were readied for the mission, the first ones airborne carrying Marines to form defensive perimeters at a landing zone at Tan Son Nhut and at the U.S. Embassy. This proved increasingly important as time progressed, as mobs of people pushed forward in an attempt to get on one of the flights to freedom. When the last helicopter departed, it radioed the following message, “Swift 22 is airborne with eleven passengers. Ground-security force is aboard. All told, 1,373 Americans and over 5,600 South Vietnamese nationals were successfully airlifted during Operation Frequent Wind.

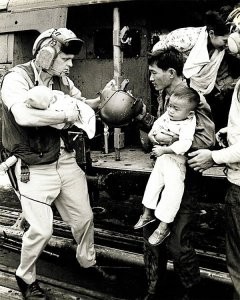

On board the ships at sea, the pace of operations was intense, with helicopters landing only long enough to disembark passengers and take on fuel. To the amazement of Captain Lawrence Chambers, skipper of Midway, one UH-1 Iroquois came aboard carrying some 50 people, much more than it was ever designed to transport. “The flight deck crew performed amazing feats keeping the landing zones cleared by expeditiously moving the aged, the sick , and the young—as well as the able-bodied—out of the danger areas at the same time that they were hot refueling and turning the helicopters around for another sortie,” he recalled later.

One of the most memorable aircraft to arrive was an O-1 Bird Dog observation plane flown by South Vietnamese Air Force Major Bung-Ly. On board with him were his wife and five children and he requested permission to land on board Midway despite the fact that he had never made a carrier landing. Presented with the decision to push millions of dollars of helicopters over the side to clear the deck for landing or risk the possible loss of Bung-Ly and his family in the event they were forced to ditch, Chambers ordered the deck cleared, the call for volunteers from Midway’s crew bringing scores of sailors to assist in the effort. When the time came for the plane to land, Midway turned into the wind, 40 knots of wind over the deck deemed necessary to keep the aircraft on deck since it did not have a tailhook. The arrival of another flight of helicopters delayed events the length of time it took them to land and be pushed over the side. Bung-Ly lined up for approach. Among those anxiously watching on deck was Petty Officer Tony MacFarlane, an aircraft director, who remembered the momentous landing.

We congregated by the island structure of the ship and awaited the Bird Dog to make its approach. When it finally touched down on the rain soaked flight deck, the pilot of the Bird Dog immediately cut the aircraft engine. As the aircraft rolled down the flight deck runway toward the end of the angled deck, my crew and I ran out into the landing area and grabbed onto the wing and horizontal stabilizer to help stop the aircraft and to prevent it from rolling off the flight deck. Once the aircraft landed, we were sure they would make it, which was why we rushed out to keep the aircraft from rolling off the ship. If he had not touched down on the deck, I do not think they would have made it around for another pass. This was the one chance. So it was pins and needles until the tires hit the deck, we knew then, that it wasn’t going anywhere.

Taking aboard aircraft was only one of the challenges confronting the crews of the Navy carriers, which now became the floating homes for thousands of additional people. On board Midway, berthing areas normally occupied by air wing personnel were instead filled by refugees, with others sleeping on mats or blankets in the hangar bay. Midway sailors prepared more than 6,000 meals for the 3,073 evacuees taken aboard. Members of the ship’s Marine Detachment provided security, in some cases disarming evacuees that arrived on board carrying sidearms and even hand grenades among all their worldly possessions. “The Vietnamese who landed were thankful, relieved and scared,” recalled Captain Ed Ellis, JAGC, USN (Ret.), who as legal officer on board Midway was placed in charge of the ship’s evacuation plan and execution. “They were thankful to get away from the Communists, relieved that they were out of danger and scared about the unknowns they faced in the future.”

The events of that April day represented a sad chapter in American history, the final act in the bitterly divisive war in Vietnam. Yet, the carrying out of their duties by sailors and Marines represented the best of America, as summarized in a special edition of a newsletter published on board Midway. “The crewmen…met the evacuees with compassionate understanding. They liberally gave of their time and attention, more than duty required. The kindness shown by the carrier’s crewmen [was] the evacuees’ first taste of American hospitality. It must have given them hope for the days to come.” The appreciation endures. Captain Tony McFarlane, USN (Ret.) attended a reunion commemorating the 35th anniversary of Operation Frequent Wind in 2010. “I saw many of the people we rescued. Many were kids during that operation, now adults,” he recalled. “With many tears they thanked us (the former Midway crewmembers), for saving their lives.”