In 1943, a young officer reporting aboard his first command, an escort carrier under construction in Tacoma, Washington, noted a homemade sign affixed to a bulkhead by some sailor as an attempt at macabre humor. It read “Torpedo Junction” in recognition of the belief that the World War II escort carriers, built quickly on merchant ship hulls, were susceptible to enemy torpedoes because they lacked the armor of their larger deck counterparts. Of the 77 escort carriers commissioned during World War II, a total of 6 were lost to enemy action, which speaks volumes about their durability given that they dodged kamikazes while supporting beachheads,, fought against overwhelming odds at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, and hunted German U-Boats in the Atlantic. For one of them, Liscome Bay (CVE 56), the “Torpedo Junction” sign would prove no joke, but a grim reality.

Named after a body of water in Alaska, Liscome Bay began her path to Pacific combat with her keel laying on December 9, 1942, at the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company Yard in Vancouver, Washington. Commissioned on August 7, 1943, the escort carrier and her crew had little time to get their sea legs, in October steaming for Hawaii to join the forces assembling for Operation Galvanic, the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. With an overall length of 512 feet and a displacement of 7,800 tons, Liscome Bay and the other escort carriers that were part of the naval forces supporting the operation were assigned to provide the vital close air support for the Marines and Army troops storming ashore. The carrier performed the task well, her embarked airplanes logging 2,278 combat sorties.

At 5:10 a.m. on November 24, 1943, Liscome Bay was part of a task group steaming 20 miles southwest of Butaritari Island at 15 knots when a lookout shouted that a torpedo was in the water heading towards the ship. Within moments the deadly underwater ordnance, one of a spread of torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-175, slammed into the escort carrier’s starboard side. It hit at the worst possible location, near the bomb magazine. The resulting massive explosions triggered when the bombs ignited killed many crewmen instantly, including some Composite Squadron (VC) 39 pilots sitting in the cockpits of their aircraft on deck awaiting the first launch of the day. Those more fortunate souls remembered the tremendous shock of the blow that threw them to the deck and into bulkheads. In many spaces steam lines ruptured and electricity went out. In some cases badly burned and in others suffering from broken bones and shrapnel wounds, the survivors made their way through shattered hatches, twisted bulkheads, and any hole they could find in an effort to reach topside so that they could abandon ship.

Among those 272 men able to go over the side was Captain John Crommelin, one of five brothers serving as naval officers. In the shower when the torpedo hit, Crommelin, who was serving as Chief of Staff to Rear Admiral Henry Mullinix, wore nothing but soap suds and suffered severe burns as he abandoned ship. Donald Cruse, who had abandoned Wasp (CV 7) when she was torpedoed the previous September off Guadalcanal, swam away from his second ship that November morning. Asleep when the explosion shook the ship, he instantly noted the smell and knew it meant bad news. An aerographer’s mate, he made his way onto a catwalk, hampered by a severed his Achilles tendon that was either hit by flying shrapnel or sliced by a jagged piece of wreckage. Observing the flight deck, he saw that the forward elevator was gone, having been blown skyward like “a cork in a bottle.” When Cruse went over the side, Liscome Bay was already listing heavily to starboard, one enduring memory of the oily water into which he plunged being a turkey, destined to be served on board the ship for Thanksgiving the next day, floating near him.

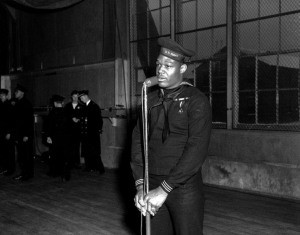

Liscome Bay sank in just 23 minutes. All told, 644 men lost their lives that morning. Among them were Rear Admiral Mullinix and the ship’s first and last commanding officer, Captain Irving D. Wiltsie. Also killed was Ship’s Cook Third Class Doris Miller, an African-American who had been awarded the Navy Cross for heroic actions on board the battleship West Virginia (BB 48) during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Navy soon announced the loss of Liscome Bay, a New York Times headline on December 3, 1943, blaring, “BABY’ CARRIER SUNK IN MAKIN INVASION; Loss of Life Feared Heavy on Escort Ship.” At the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company, an announcement over the loudspeaker informed employees about the sinking of the ship they had known as Hull 302 when building her. The wounded made their way home, Donald Cruse ending up in Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, where he received a visit from movie actress Joan Crawford and had a Purple Heart pinned on him by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Lieutenant Commander Marshall U. Beebe, skipper of VC-39, went on to become a fighter ace and, in the Korean War, an inspiration for author James Michener, who dedicated his book The Bridges at Toko-Ri to Beebe. John Crommelin would eventually lose two of his brothers in the war. Whatever happened afterwards, all surely never forgot the day that changed their lives and ended those of so many shipmates.