For most Americans, the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came through the crackling voice on the radio and screaming newsboys on city street corners. Yet, for number of civilians, many of them the wives and children of servicemen stationed in Hawaii on that fateful Sunday morning, routines were violently interrupted by the roar of airplanes and the billowing black smoke over Battleship Row. The memories of that day were seared into their consciousness, the experiences of one of them penned in a letter back home to give family members a sense of what had occurred half a world away.

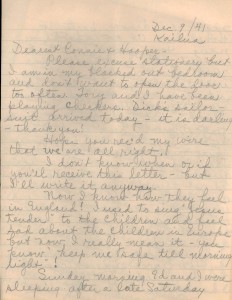

“Please excuse the stationary, but I am in my blacked out bedroom and don’t want to open the door too often,” wrote Jane Colestock two days after the attack. For her and her husband, Lieutenant Edward Colestock, the morning of December 7th began with a voice on the telephone yelling, “My God get him up! It’s a matter of life and death!” Rising from their bed, she and her husband looked out the window and saw the Japanese planes flying over Naval Air Station (NAS) Kaneohe. As Commander Colestock hurriedly dressed to head to the air station, his wife recounted in her letter, she uttered, “Oh Ed, I don’t want you to go over there,” to which he replied, “I guess there’ll be a lot of things you don’t want from now on.”

She then went on to describe the aftermath of the attack. “Our car has a machine gun bullet hole in the rear window and a tire…was shot off…Superficially the station looks the same except for the skeleton of a burned hangar, wreckage of a Japanese plane scattered on the hill and of course gun emplacements, brownish-green dyed white uniforms on the sailors, helmets, rifles, pistol belts, unshaven officers etc.”

In the two days following the attack, during which she was able to see her husband for only about five minutes, she experienced the sudden shift in the way of life she and her family had known in Hawaii, writing “If I live thru it, I’ll be glad not to have missed it.” Air raid sirens were frequent, hastily dug trenches now traversed her lawn, and civilians were limited to four cans of food at the base commissary. Additionally, one evening she was startled by soldiers pounding on her front door demanding to be let in. “Turns out a wire and a palm tree are making connections and [creating] blue sparks on my roof and I am a saboteur flashing signals.”

After a wearying few days, the young Navy wife found herself concluding her letter while listening to the radio, the children asleep, her son grasping a stick that he was going to use to shoot down enemy planes. “’Be calm…planes are sighted off P.H. [Pearl Harbor] but may be friendly,’” an announcer proclaimed. Then came the voice so familiar to that generation, that of President Franklin D. Roosevelt “with a beautiful speech and the planes turned out to be ours,” a brief respite from worry in a world turned upside down.