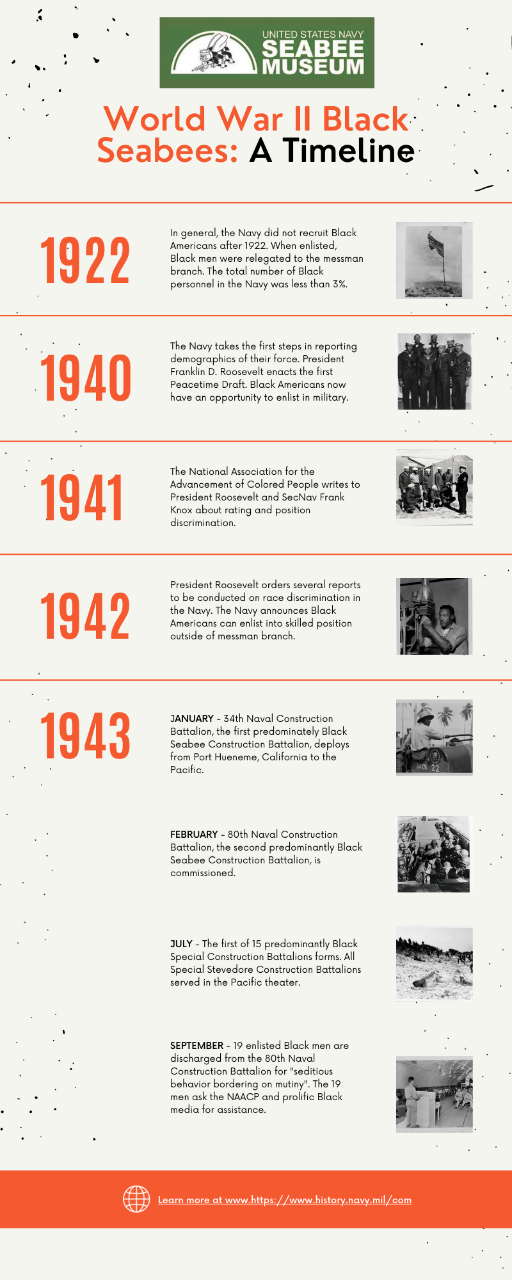

Black Seabees in World War II

34th Naval Construction Battalion Seabee operating a bulldozer, [1944]. Courtesy of United States Navy Seabee Museum Archives.

Fighting for Enlistment Equality

The fight for equality and representation for Black men in the armed forces was two-fold: one where the men in service uniforms were proving their worth and capabilities to be more than just that of messmen, and one where their families, friends, and allies were using media and organizing to demand more from the federal government.

As the United States began to strategize less military isolationism and more action against Italy, Japan, and Germany they looked at the number-strength of their men in uniform. In general, the Navy did not recruit Black Americans following 1922.(4) In June, 1940 the Navy began its debate of increasing their enlistments by evaluating their exclusionary policies. A total of only 4,007 personnel in the entire Navy were Black Americans in June, 1940.(1) Notably, the Black enlisted personnel were strictly coal heavers, cooks, messmen, or stewards therefore holding no skilled positions or positions of authority. By 16 September, 1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted the Nation’s first peacetime draft by signing into law the Selective Training and Service Act. (Can link to the LOC document) The new legislation stated “any person, regardless of race or color...shall be afforded an opportunity to volunteer for...the land and naval forces of the United States.”(5) Navy Secretary William Franklin (Frank) Knox assembled a small team of advisers to investigate the United States Marine Corps and United States Navy to distinguish fit for Black Americans’ servitude.(2) The committee met three times before unanimously deciding in December, 1941 that “...the enlistment of Negroes (other than as mess attendants) leads to disruptive and undermining conditions” as well as “...a limited number of qualified Negroes could be enlisted for duty on some types of patrol or other small vessel assigned to a particular yard or station.”(2)

A calculated rebuttal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on 7 December, 1941 took a stand against the decision and pressed President Roosevelt and Navy Secretary Knox for reconsideration. (Digitized - link to object) Afterall, President Roosevelt’s Selective Training and Service Act intentionally stated that “...in the selection and training of men under this Act, and in the interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color.”(2)

President Roosevelt took into consideration the NAACP’s resistance to the committee and insisted that further studies be conducted to find rated positions for Black enlistees. Following two additional failed reports telling President Roosevelt that Black men were suited only for the messman branch, President Roosevelt contacted SecNav and insisted they find rated positions for 5,000 Black enlistees. At long last President Roosevelt received the following from a 25 February, 1942 report from Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold R. Stark that read:

“If, however, men of the colored race are to be enlisted in the Navy in ratings other than in the messman branch, CNO recommends their enlistment in the Reserve, and their assignment to (1) Construction Battalions under the Bureau of Yards and Docks; (2) Shore Stations, for work around docks or general labor such as now performed by enlisted men, or could be so performed in places like Naval Supply Depots, Navy Yards, Ordnance Stations, Training Stations, Experimental Stations. Section Bases, Air Stations, etc., - in general - the Naval Shore Establishment; and (3) Yard Craft. Of the above listed alternatives, the Chief of Naval Operations would prefer recourse to (1) and (2) only. Alternative (3) has been included in case it is necessary to assign billets afloat.”(2)

On 7 April 1942, the Navy announced that beginning 1 June, 1942 Black Americans could enlist for general service in addition to the messman branch. Enlistment grew quickly as pressure mounted for the Navy to expand their programming for Black enlistees.

“By December 31, 1943 there were 101,573 Negroes on active duty in various rates, 37,981 of whom were Stewards Mates (about 36%). June 30, 1944 saw a total of 142,306, of whom 48,524 were Steward's Mates (about 33%). The figure for December 31, 1944 indicated the leveling off of growth, with a total of 153,199, including 52,994 Steward's Mates (about 34%).As the war reached its climax, on June 30, 1945, the Navy counted on active duty 165,500 colored enlisted personnel. 75,500 of these were Steward's Mates (about 45%). As of June 30, 1945 about 123,000 colored personnel had served or were serving overseas.”(3)

Reportedly, by February 1, 1943 there were 2,020 Black men enlisted into the Seabees.(1)

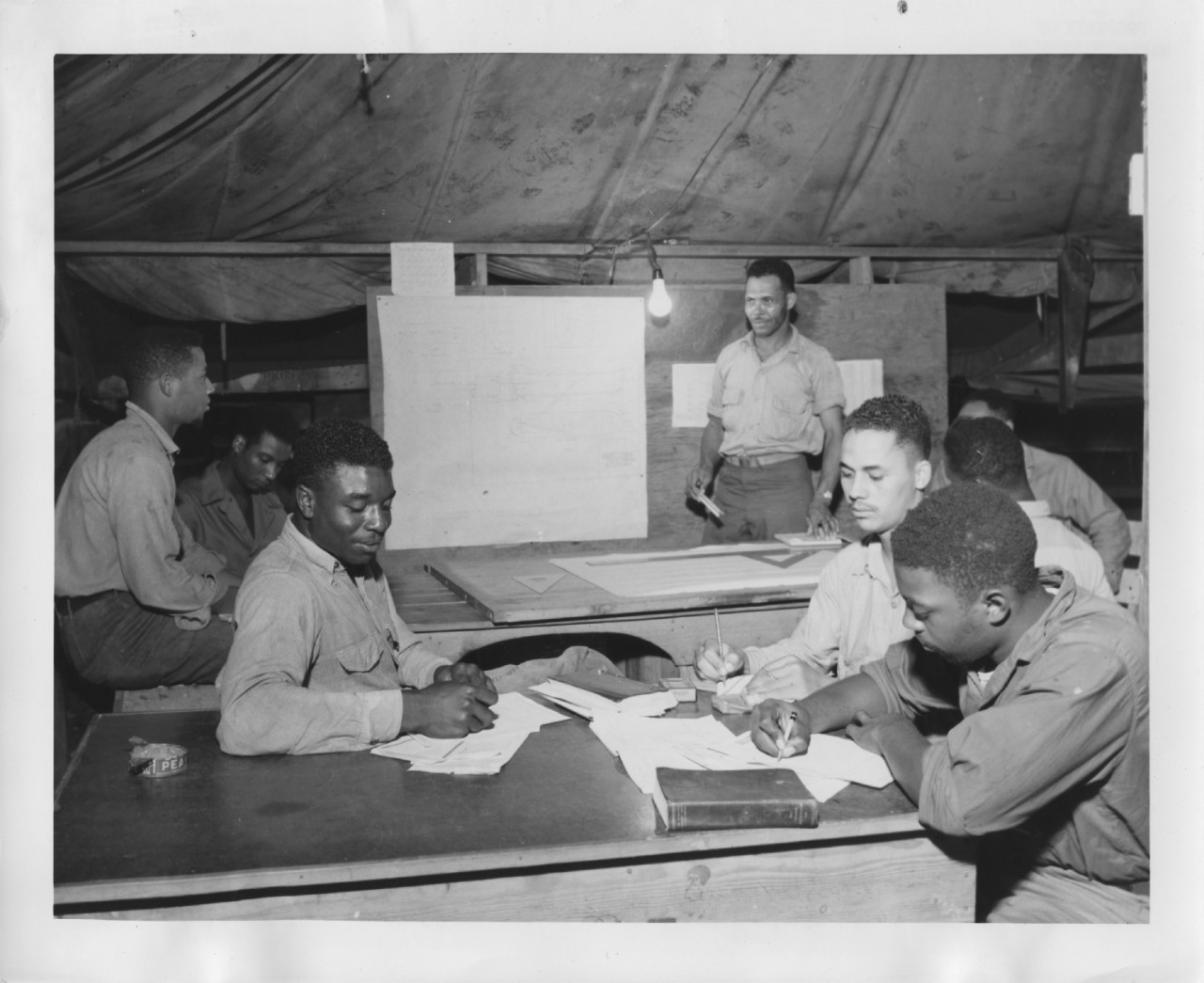

Seabees from the 34th Nval Construction Battalion studying carpentry in class at Camp Kukum, Guadalcanal, 13 July, 1944. Courtesy of the United States Navy Seabee Museum.

Black American Seabees

Within the Navy, the Bureau of Yards and Docks (BuDocks) began active recruitment of Black men for mostly segregated construction battalions in April, 1942. Recruitment averaged at around 277 men each week for the entire Naval force.(1) By September of that year, 880 Black men from 37 states enlisted as Seabees and reported for duty at Camp Allen, Norfolk, Virginia. Units were to be trained by white officers and in segregated training facilities with the intention of being fully restricted from combat vessels.(1)

The first Naval Construction Battalion (NCB) to form under the new regulations was the 34th who commissioned 23 October, 1942 in Norfolk, Virginia. The Black Seabees in this battalion were highly skilled in over 50 different trades ranging from electricians, carpenters, black smiths, painters, riggers, draftsmen, and steelworkers. The 34th was composed of 880 Black Seabees and 280 white officers and senior enlisted. Following their training, the 34th NCB were stationed at Port Hueneme, California in preparation for their 20-month long deployment to the Pacific Theater.

Following the 34th NCB was the second predominantly Black Seabee battalion. The 80th NCB commissioned on 2 February, 1943 at Camp Allen, Norfolk, Virginia. The demographics of the battalion resembled those of the 34th with a high proportion of Black enlistees to white officers and senior enlisted. The 80th completed training in Norfolk, Virginia and were quickly stationed at Gulfport, Mississippi before their deployment to Trinidad in July, 1943.

Seabees from the 34th Naval Construction Battalion posing with their awarded Purple Hearts, 1943. Courtesy of the United States Navy Seabee Museum.

Rough Waters

Discriminatory policies, long in place before the enlistment of Black recruits, throttled the patience and success of the newly enlisted men. The dissemination of power and the structure of the battalions systematically disenfranchised lower-enlisted men when reporting racial inequalities and mistreatment. “By 1944, the Seabees, which were still segregated, accounted for only 10% of the African Americans in the service.”(1)

Therefore, with tensions high and the stress of war ever-burgeoning on the horizon, the segregated construction battalions began to disassemble themselves.

Shortly after beginning their deployment in Trinidad, the 80th NCB caught the attention of Black media outlets who were circulating a letter received from a Seabees in September, 1943. The letter detailed a number of ways in which Black men in the battalion were being treated unjustly. The author of the letter explained unequal promotion opportunities, constant racial slurs and aggression, and the failure of his leadership to listen to the grievances of Black men. The letter was sent to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) before the media got hold of the story.

The Commanding Officer of the 80th had taken the aforementioned complaints from the Black Seabees, of which 19 were specifically identified, and used their complaints as grounds for a dishonorable discharge claiming the 19 men were guilty of seditious behavior bordering on mutiny. (provide digitized letter/report)

The NAACP was made aware of the discharges and began an earnest appeal to the Secretary of the Navy to upgrade the discharges of the 19 men. With pressure coming from the Black media, the NAACP and their special council Thurgood Marshall, as well as other Black Seabees currently on deployments an investigation was launched.

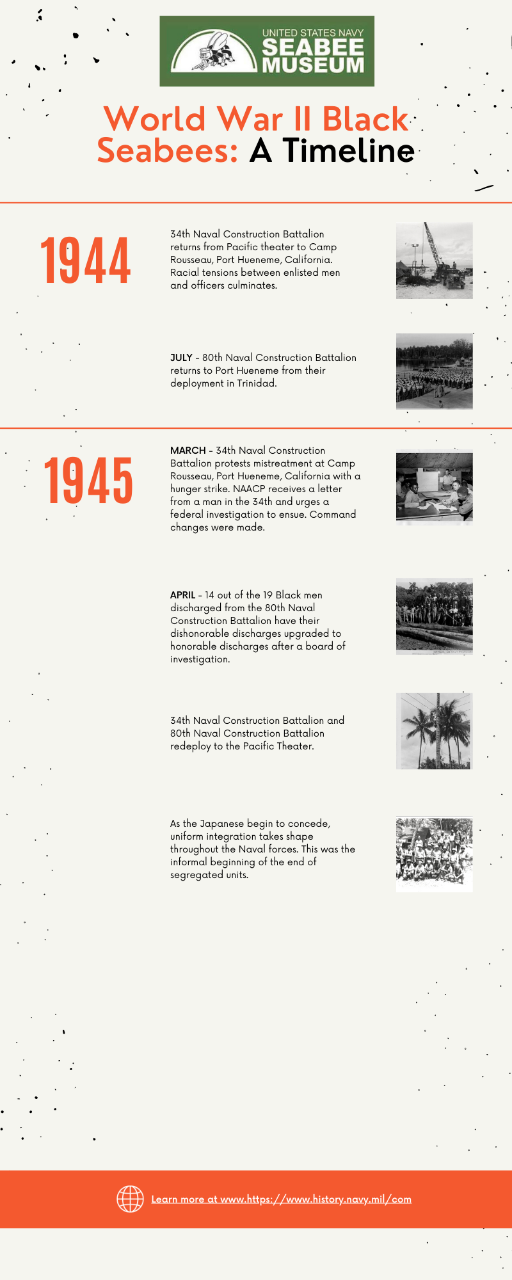

Still under heavy investigation, the 80th NCB returned from their Trinidad deployment to Port Hueneme, California in July, 1944. In transit, a reported 744 Black enlisted men staged a protest over their disagreement with segregation in the Caribbean.(1) Naval investigators cited leadership problems as a major factor in these and subsequent incidents. Upon arrival and by order of BuDocks, the commanding officers and chiefs were relieved of their duties in the 80th NCB. BuDocks then made a conscientious decision to restaff the positions with officers from northern states as opposed to the previously southern officers.

By April, 1945 the investigation review board decided to upgrade the dishonorable discharges of 14 out of the 19 men to an honorable discharge. A small victory well captured in newspapers across the nation.

During this time, the 34th NCB returned from their deployment in the Pacific to Camp Rousseau, Port Hueneme, California in late 1944. While preparing for their second deployment the racial discrimination became eminently clear for the enlisted men. The commanding officer of the 34th refused to rate any Black Seabee as a chief petty officer all the while instituting segregated barracks and mess arrangements. The Black petty officers were degraded of their rate and given unskilled labor jobs and denied any opportunity to lead working parties.

In March of 1945 morale sank to an ultimate low for the Black Seabees of the 34th. To take matters into their own hands and draw attention to their grievances, the men protested with a hunger strike that lasted over two days. During this time, the men refused all food but continued their work. BuDocks was informed of the protest and the grievances of the men and launched an investigation into the battalion’s command. Shortly thereafter, the commanding officer, executive officer, and roughly 20% of the remaining officers and petty officers were relieved of their duties with the 34th. BuDocks looked to spearhead discrimination before restaffing and issued a statement that the replacements would be screened for any racial biases prior to assignment. Notably, the new on-coming commanding officer was a New Yorker who promised the men rerates and promotions. Again, the Navy found itself discerning the fitness of their leadership by taking into account where they fell across the racial lines that divided the United States.

Additional Resources

References

|

“‘Many of them are among my best men’: The United States Navy Looks at its African American Crewmen, 1755-1955”, Dissertation, Kansas State University, 2011. |

|

|

“The Negro in the Navy: United States Administrative History of World War II #84”, Historical Section, Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1947. |

|

|

Yearbook of Naval Personnel Statistics, 1944, Table 8 ("Negro Ratings: Number of Negroes on Active Duty by Rates," (1943-1944), and table 27 ("Duty Assignments of Negro Enlisted Men Rated and non-Rated Negroes on Board Various Activities, 31 December 1944"). The 1945 figure is from the files of the special programs unit, Planning and Control Activity. |

|

|

Manning in the US Navy, Naval Heritage and History Command. |

|

|

United States Code: Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, 50a U.S.C. §§ 302-315 (Suppl. 1 1940). |