The SeabeeGram, Volume 3

The SeabeeGram Volume 3 [PDF, 1.7 MB]

Museum News

The museum is now open Wednesday through Saturday from 10am to 4pm.

To help ensure physical distancing and a safe, comfortable experience, the number of visitors in the museum is limited and visitors are asked to follow these guidelines:

- In accordance Navy guidance, mask wear for fully immunized personnel (two weeks beyond final dose) is no longer required indoors or outdoors at DoD facilities. Immunized visitors should continue to comply with Centers for Disease Control and prevention guidance regarding areas where masks should be worn.

- Please do not enter the museum if you feel sick or have a temperature over 100 degrees.

- Exhibits requires one-way foot traffic flow.

- The STEM Bee Fun Zone is temporarily closed.

- The Seabee Museum Archive Reading is temporarily closed to researchers.

- Maximum museum capacity is 60 visitors.

- Official Navy Events and Ceremonies for groups of 50 or less; make a reservation.

- In-person tours available for groups of 10 or less; make a reservation.

For the most updated visitor information, follow the museum on Facebook or visit the museum’s website.

Exhibit Opening: In celebration of 10 years in the new museum in Port Hueneme, USNSM is opening an exhibit called “Breaking Ground: The Transformation of the U.S. Navy Seabee Museum” on August 27, 2021. This exhibit that explores the history of the museum from its humble beginnings in 1947 through the Quonset hut years and the present day.

Director’s Notes

The USNSM reopened to the public on June 2nd after being closed for almost 15 months due to COVID. There were people waiting at the front door of the museum on the morning when it first opened and visitation has continued to be steady. Thank you to all who have visited! One very special guest was BU3 Dave Evans who served in NMCB-8 from 1967 to 1969. He came to Port Hueneme from Illinois on an honor flight just to see the museum. The trip was organized by The Veterans Garage, non-profit organization that brings together Military Vehicle owners. The museum staff was grateful to be able to meet BU3 Evans and be a part of his journey.

This edition of the newsletter commemorates the 30th anniversary of eruption of Mount Pinatubo and the Seabees involvement in the cleanup. The Seabees role in disaster recovery both nationally and internationally highlight their ingenuity in ways that not even wartime captures. In the following article CAPT Mark Libonate, CEC, USN (ret) captures the resourcefulness that Seabees can muster under extraordinary circumstances. At the time of the eruption, then LT Libonate was Commanding Officer of CBMU-302. The unit was stationed in the Philippines and tasked with providing base operations support throughout the Pacific when required, as well as humanitarian assistance in the Philippines.

Happy history hunting,

Lara Godbille, Ph.D.

Director, U.S. Navy Seabee Museum

Naval History and Heritage Command

Kickin’ Ash and Taking Names by CAPT Mark Libonate, CEC, USN (ret)

In early April 1991 when the first plumes of smoke escaped from the mountain, no one could foresee the incredible events that would unfold two and a half months later and provide the stage for yet another chapter in the history of the Seabees. Following those initial spurts from Mount Pinatubo, volcanologists descended on the Philippines and began closely monitoring the seismic activity. In the coming weeks it became apparent that the volcano would erupt, but the timing was impossible to pinpoint. After numerous “mini” eruptions and earthquakes, on June 10 the order was given to evacuate Clark Air Base which sat roughly eight miles from Mount Pinatubo. Over the next few days, approximately 15,000 people left Clark AB and descended upon Subic Bay Naval Base and Cubi Point Naval Air Station.

Operation Fiery Vigil was initiated and the massive evacuation roughly doubled the population at Subic Bay. Families were lodged in every possible place on the base, from vacant Navy homes to the chapel and school. Sailors consolidated in the bachelor quarters to open rooms for evacuees. Seabees from Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit-302 stationed at Subic and from Naval Mobile Construction Battalion THREE, on deployment at the time, turned to and supported the evacuation in any manner possible. Makeshift processing centers and supply areas were hastily fashioned, racquet ball courts and other areas were modified into kennels and supplies, and personnel were transported wherever needed to support the massive influx of personnel.

The real action would come on the morning of what became known as “Black Saturday”, June 15, 1991. At the time of the eruption, the crews from CBMU-302 and NMCB-3 were hard at work assisting evacuee operations. From just about any vantage point on Subic or Cubi, the initial eruption could be seen as the mountain’s fury threw roughly half a cubic mile of material towering miles into the air. A short while later, ash (much like a fine sand) began to sprinkle down on the base. And then the perfect storm happened (no pun intended). While all indications prior to any eruption were that the majority of the ash would be carried by the winds out to sea and that Clark AB would suffer the greatest impact of the US bases in the Philippines, Typhoon Yunya changed all of that. The typhoon had come ashore north of Mount Pinatubo and though degraded to a tropical storm at the time of the eruption, carried much of the ash southward on a direct path to Subic Bay about 25 miles away. By noon, the sun had been completely erased from the sky and a deep darkness descended on the base. The sand that continued to fall was now wet, the air was filled with thunder and lightning, the ground trembled, buildings were shaken by the numerous earthquakes…and Seabees continued to work.

Public Works Center Subic Bay had opened an emergency operation center and called on the Seabees to completed numerous tasks during the storm. These included responding to buildings that were damaged or collapsed to ensure no one was trapped inside or hurt, refueling generators, and attempting to protect several critical facilities, such as the water treatment plant. With a true Can Do spirit, the Seabees fought through the challenge of wet ash that stuck to everything – especially goggles – and an ever-changing landscape as the ash piled up and often made the roadways indistinguishable from their surroundings. As the day turned to night, the ash continued to fall and the calls for response slowed. CBMU-302 relocated its command center and personnel to a barracks building as their headquarters succumbed to the weight of the wet ash on the roof, but they remained on call. The night brought with it a light show like none other. The sky lit up with every lightning strike in a bright red that seemed to travel in lines as it made its way through the mineral debris that filled the air. The entire base was hunkered down waiting for the ashfall to end.

As the ashfall began to cease and light returned slowly the following morning, the base was somewhat unrecognizable and the devastation immense. The entire base was covered with up to a foot of ash and between 150-200 buildings, mostly pre-engineered buildings and tension-fabric structures, had collapsed or were damaged beyond use. The lush jungle greenery throughout the base was completely stripped. The greatly expanded population was now without power or water. It was time for the Seabees to go to work!

As anyone with knowledge of the Seabees could expect, in no time at all Seabees were doing what they do best – clearing roads, assisting with emergency power, assisting with repairs to the water treatment plant and clearing a 5,000-foot strip of the NAS Cubi Point airfield to permit C-130 landings for critical supplies and evacuations. When you think about the fact that Subic and Cubi comprised the United States’ largest overseas installation at the time, the sheer magnitude of the task was daunting. Over the coming week or two, the Navy sortied ships to evacuate all non-essential personnel - including Navy families.

With limited manpower and equipment, the 90 Seabees of NMCB THREE and the 50 Seabees of CBMU-302 fought through the challenges before them and were soon joined by an additional 100 Seabees from NMCB THREE’s main body in Guam. In the coming weeks, a large detachment of Seabees from NMCB FOUR which was scheduled to deploy to Okinawa was redirected to assist in the recovery efforts. Later a small group of Seabees from NMCB FIVE arrived to provide training and support as well. A Battalion Table of Allowance, on the way back from Desert Storm, and one from Port Hueneme were sent to provide additional capacity for clean-up efforts.

After the initial response efforts, the Seabees began to tackle the herculean task of getting the base back in working order. Ash moving operations were a massive undertaking. Spoil areas were designated throughout the base to haul and deposit the ash as roadways and drainage were cleared. NMCB FOUR had the tremendous undertaking of returning the airfield at Cubi point to full operational status.

The power distribution system suffered damage from falling trees and down poles, but the largest challenge was clearing the mineral rich ash from the lines. With limited bucket trucks available, Seabees used gaffs to climb nearly every power pole on the installation, and wipe down each line, insulator, and transformer. Where needed, downed poles were replaced and new line was hung. Additionally, Seabees from Naval Facilities Engineering Command’s Mobile Utilities Support Equipment (MUSE) unit operated large generators to supplement the base’s power plant as repairs were conducted.

And then there were the downed structures. The buildings that fell in many cases held critical supplies that could aid in both the initial contingency and then the longer-term recovery. Additionally, the Naval Magazine suffered significant damage to pre-engineered buildings storing munitions. Across the installation, Seabees were tasked with removing these structures to recover these critical assets, make the areas safe and set the stage for a potential reconstruction effort. As supplies flowed in, K-span structures were erected to provide covered storage and support the resumption of operations.

By the fall of 1991, both Subic Bay NB and NAS Cubit Point were well on the way to resuming “normal operations” thanks to the combined Seabee force! Seabees had executed what is arguably the US Navy’s largest earth moving operation since Cubi Point was constructed from the jungle covered mountain in the 1950’s. In looking back on the recovery efforts, I am reminded of a comment by RADM (ret.) Thomas Mercer, Commander US Naval Forces Philippines: “Whenever I see a sailor, working hard, covered in ash and smiling ear to ear, I know it is a Seabee.” As it is today, thirty years ago this month, the Seabee legacy was alive and well.

From the Collection

Over the years, the U.S. Navy Seabee Museum staff have written historical articles about the Seabees which are all available on the museum’s blog site. These articles are written on a wide-range of topics from ranging in topic from the importance of U.S. Navy bases to the invasion of the Normandy to the construction of the Seabee Memorial. As part of the daily work, the museum staff works with the collections to research and learn more about the contributions of the Seabees and the Civil Engineer Corps. One example is the “Curator’s Corner: The “Ash Kick’n’ Seabees” and Mount Pinatubo” that tells the story using a plaque that is in on exhibit at the museum as a centerpiece.

Seabee Corner

Last issue we asked: What was your favorite construction project and why?

Here are some of the answers we received:

Building sea walls, ramps and building in Bermuda in1943. The people were friendly and I enjoyed the liberty in Hamilton. – Daniel S.

Cubi Point. The Seabees did a tremendous amount of work. – John M.

Hospital barge in Lake Titicaca in Bolivia. – Oscar P.

The Seabee Corner question for this issue is going to be a little bit different:

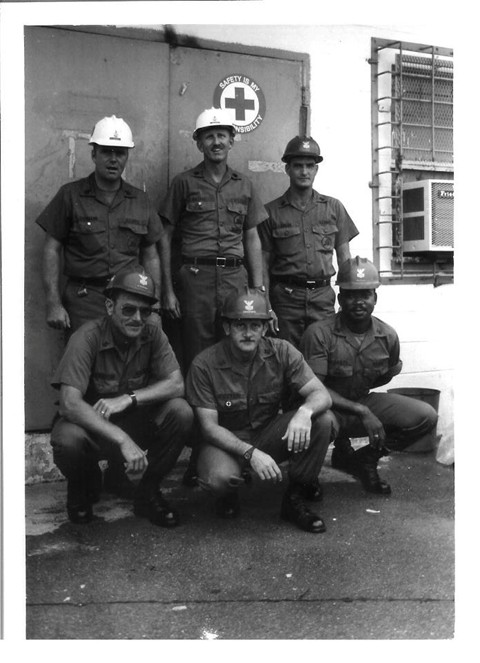

Do you know who is pictured in this photo?

The museum staff found this in the photos related to Mount Pinatubo, but the most specific information on it is “Group – NMCB 4.” If you know who these Seabees are, please email the museum at SeabeeMuseum@navy.mil. We will share our findings in the next newsletter.

Connecting on Social Media

Follow the museum on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for On This Day in Seabee History, interactive activities, insights into museum operations, and other fun information!

USNSM Website: https://www.history.navy.mil/seabeemuseum

USNSM Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/seabeemuseum

USNSM Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/usnavyseabeemuseum

USNSM WordPress: https://seabeemuseum.wordpress.com

USNSM YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/SeabeeMuseum

USNSM Twitter: https://twitter.com/SeabeeMuseum

Seabee Historical Foundation

The SeabeeGram is published with support of the Seabee Historical Foundation (SHF). The SHF is the non-profit charitable partner of the U.S. Navy Seabee during Museum chartered to support the museum and its programs. For more information about the SHF, visit their website at www.seabeehf.org.

Contact Us

Museum Staff is always available to assist you with Seabee-related historical questions or museum operations questions.

General museum operations questions contact: SeabeeMuseumVisitor@navy.mil

Historical/reference questions contact: SeabeeMuseumArchive@navy.mil

Information about donating historical material contact: SeabeeMuseumCollections@navy.mil