Tall Towers in France

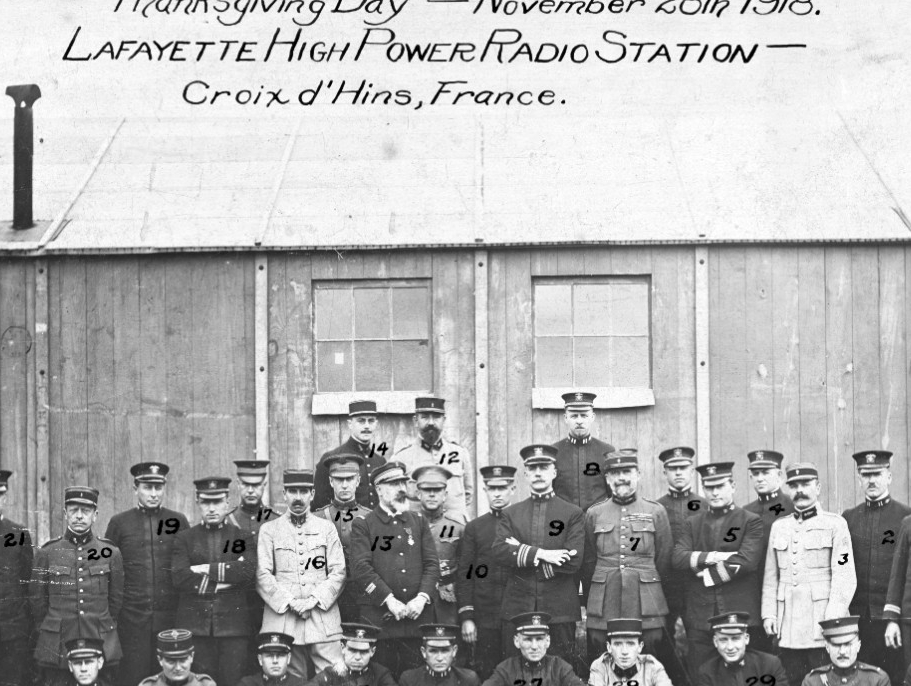

Station officers pose for a Thanksgiving Day Photo, 28 November 1918. Names of all those numbers are on the reverse of the original. (NH 85661)

Before World War I the Navy had been named the exclusive agent for U.S. government radio operations because of its pioneer interest in long range communications. When war broke out, fleet expansion and a concurrent expansion of the then small radio communications network was imperative.

Prior to U.S. entry into the conflict, the Bureau of Yards and Docks had constructed towers and transmitter sites with structures, utilities, and personnel support facilities for the Bureau of Engineering. New high-powered stations became operational at San Diego, California; Cavite, the Philippines; and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, almost simultaneously with the declaration of war. These stations each consisted of three 600-foot triangular steel towers with attendant facilities. Shortly after the declaration of war, a four-tower installation became operational on the Severn River, across from the Naval Academy. This last communication station was billed as the “second most powerful radio station in the world” -- the most powerful of the time being that of the American Marconi Company at Brunswick, New Jersey. More powerful station were, however, yet to come.

In the latter part of 1917 General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, requested that a mammoth communication station be constructed in France. The AEF commander was concerned that existing stations either were overloaded or could be easily interrupted by enemy jamming. In similar fashion, Pershing thought the transatlantic cable was particularly vulnerable to German undersea attack.

In response to General Pershing's request, the Bureau of Yards and Docks designed what was to become the largest radio installation of its kind. Eight 820-foot towers were to be constructed at Croix d'Hins a site 14 miles southwest of Bordeaux. The project was also to introduce the use of a naval construction force for such projects, a force which was the forerunner of the modern Seabees. This came about when the French government vetoed the use of American contractors because of the great wage disparity between contract employees and those in the local labor market. The French also believed that the construction should be carried out by personnel under military discipline. The U.S. Navy agreed and a search began for naval personnel with the necessary steel working and electrician skills. Such men were readily found as members of the 12th Regiment (Public Works) at the Naval Station/ Great Lakes, Illinois, where they had been employed in building the facilities needed to house and train the thousands of recruits pouring into the station.

Although the radio transmitters and antenna installation were the responsibility of the then Bureau of Engineering, an eleven-mile electrical transmission line was designed and built the camp which would house the construction crews; it consisted of 20 barracks, a mess hall, specialty warehouses, a refrigeration plant, a laundry, and even a small hospital.

Logistics and language proved a problem inasmuch as German submarines still prowled the English Channel and the rudimentary French spoken by the Americans proved tres amusant to their hosts. The French, no novice tower builders themselves, supplied technical experts and expediters to clear the tangle of red tape created by the two governments. When the magnitude of the project became apparent, the station was renamed the "Lafayette Radio Station•• by Presidential direction; it had initially been unofficially called the "Liberty" radio station.

When the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, four of the towers were nearing completion -- incredibly without the loss of a single life or even a serious injury. Although the war had ended, the French wished the station completed for postwar use and requested that

U.S. Navy management of the project continue. The Bureau of Yards and Docks, confronted with rapid demobilization of its uniformed work force, contracted, now with French concurrence, an American construction firm to complete the project. The camp, still under Navy administration, was occupied by contract workers who termed its amenities "ideal." Although the contract called for completion of the project by 14 January 1920, the Civil Engineer Corps officer in charge of construction turned the completed station over to French government representatives on 1 December 1919, 44 days ahead of schedule.