USS San Diego (ACR-6)

Armored Cruiser No. 6

History

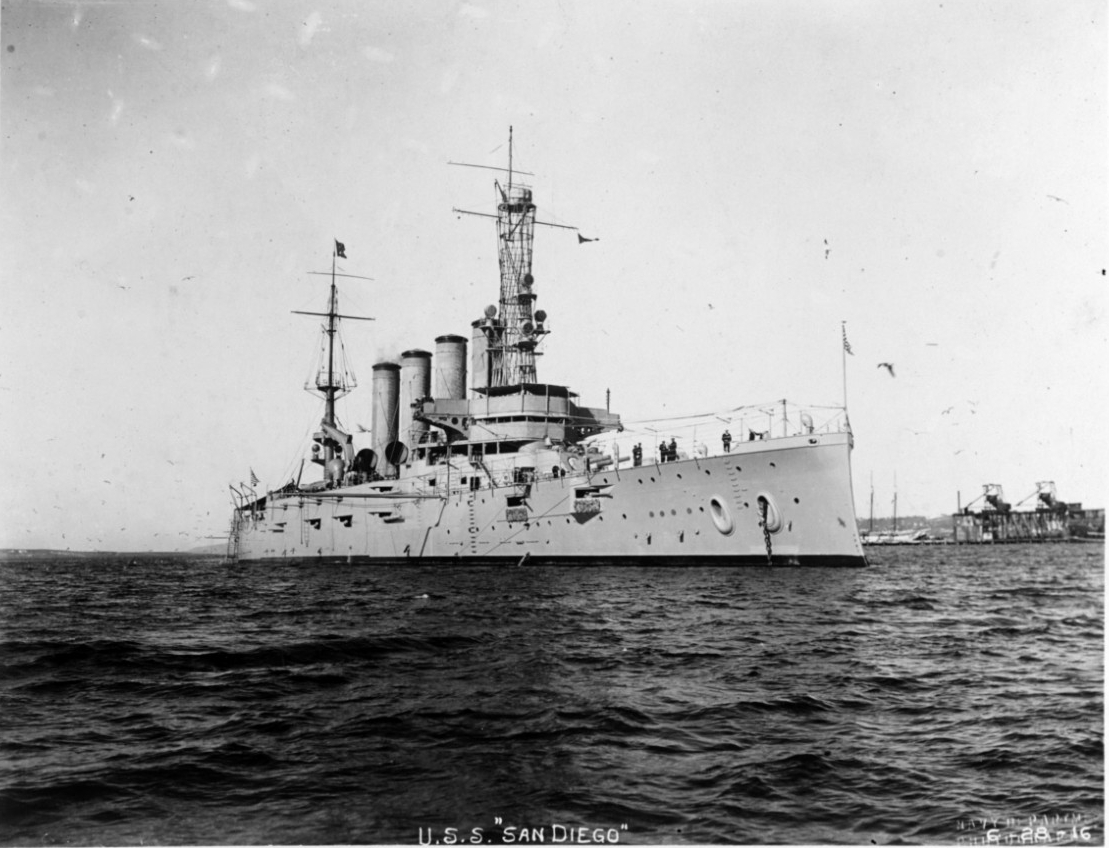

Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. Navy recognized a need for ships capable of protecting the nation’s overseas territories and sea lanes. The Navy designed a 12,000-ton armored cruiser, which traded firepower for speed and would be able to outmaneuver enemy formations while not sacrificing armor, thanks to recent improvements in steel. Authorized by Congress in 1900, six such armored cruisers, starting with Pennsylvania, were laid down in 1902. Unfortunately for the Pennsylvania-class, due to the speed at which military technology changed, these armored cruisers did not prove viable for their planned purpose. By 1904 the development of the steam turbine, combined with a study of tactics employed in the Russo-Japanese war, determined that armored cruisers were best used to provide auxiliary support to big gun battleships.

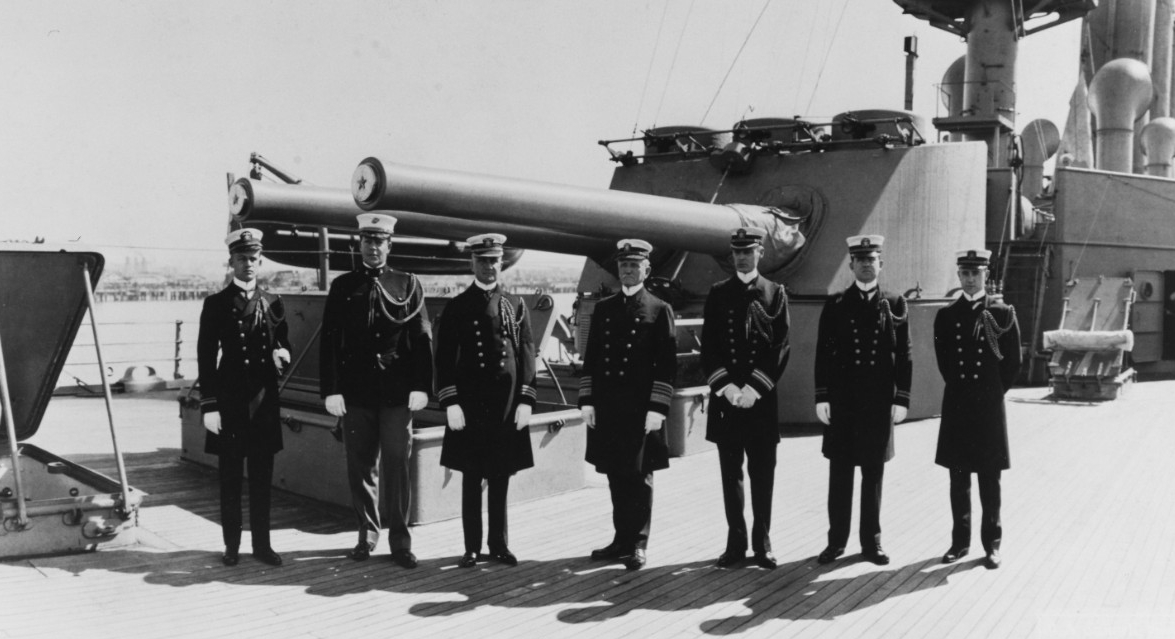

San Diego was launched on April 28, 1904 as armored cruiser California (Armored Cruiser No. 6) sponsored by Miss Florence Pardee, daughter of California governor George C. Pardee, and commissioned on 1 August 1907. Assigned to the Pacific Fleet, California operated along the West Coast conducting training exercises and drills until she was sent to Honolulu, Hawaii, in 1911. The vessel then served on the Asiatic Station visiting the Philippines, China, and Japan in early 1912, before being ordered to Nicaragua to protect American lives and property during a time of political upheaval in that county.

California was renamed San Diego on 1 September 1914 to bring the Navy into compliance with the policy that reserved state names for battleships, and subsequently designated the flagship of the Pacific Fleet. On 21 January 1915, the ship suffered an explosion in her No. 1 fire room, killing five Sailors and injuring seven more. Ensign Robert Webster Cary, Jr and Fireman Second Class Telesforo Trinidad received Medals of Honor for their actions during the fire to save their fellow crewmen.

Following America’s entrance into World War I in April 1917, San Diego operated as the flagship for Rear Admiral William F. Fullam, commander of the Patrol Force U.S. Pacific Fleet, until reassigned to the U.S. Atlantic Fleet in July. Once there, the crew’s mission was to escort convoys through the dangerous and submarine-infested North Atlantic on the first leg of the voyage to Europe.

Loss

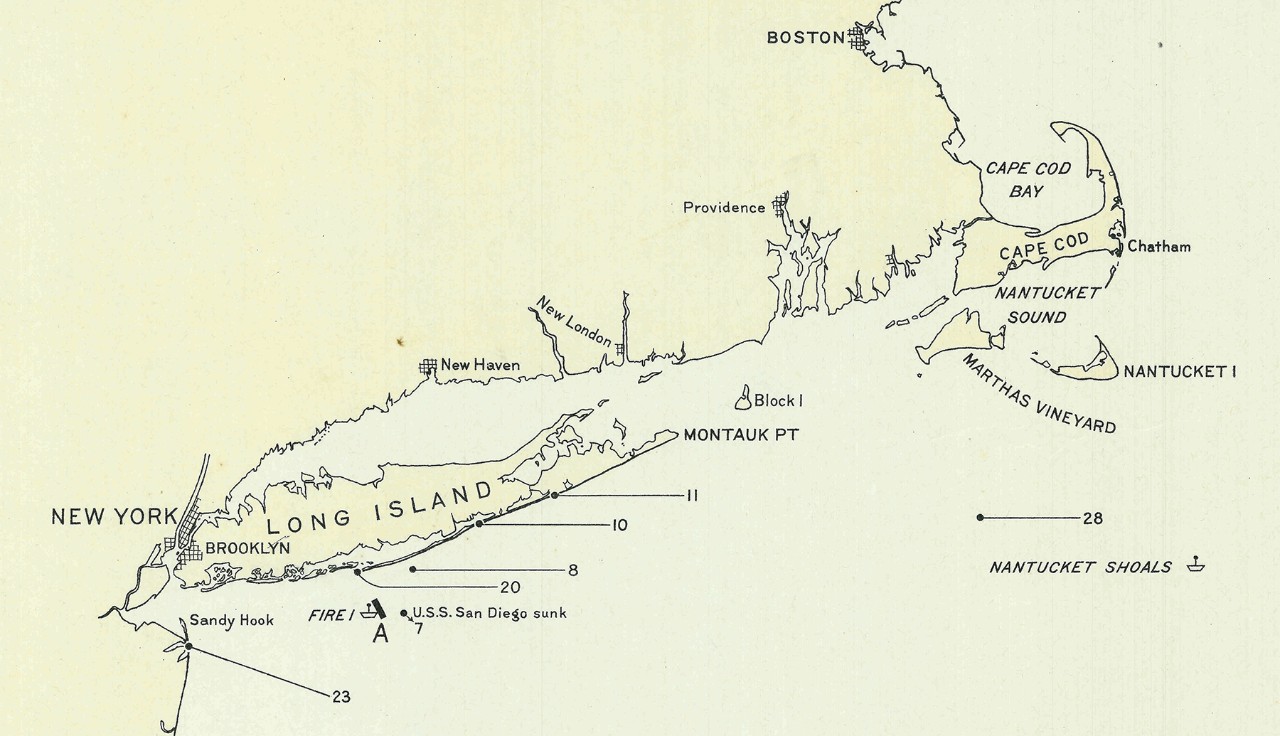

On 19 July 1918, while en route from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to New York, Captain Harley H. Christy had his crew in watch positions as the area was known to be a hunting ground for German submarines in search of allied shipping. Despite these measures, at 11:05 a.m. San Diego was rocked by an explosion on the port side below the waterline, immediately causing the ship to list to port. Christy, believing the explosion to be the result of a German mine or torpedo, ordered evasive maneuvers to avoid a second attack, but the engines had been rendered inoperable. The cruiser was rapidly taking on water and the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship. Of a crew of 1,183, six Sailors were lost in the sinking.

San Diego went down between 100 and 110 ft. (30.48–33.53 m) of water off the coast of New York near Fire Island. As the Navy received word of the incident, aircraft were dispatched to the area to try and locate any U-boats that may be nearby. Aircraft from the First Yale Unit dropped multiple bombs on what they believed to be a submerged U-boat. Surface vessels arriving at the site, however, collected papers and photographs that floated to the surface after the bombing, revealing that the target was actually San Diego and not a U-boat.

The Navy conducted its first survey of the wreck in 1918 for an initial site assessment. The dive team verified the site as that of San Diego, lying upside down and resting on its stacks, and revealed areas where the aerial bombs had been dropped on the wreck during the alleged sighting of a German submarine. The divers also recovered a tapered steel plate judged to have come from the engine room bilge. The Navy visited the site two more times during 1918, primarily to take soundings to determine whether the vessel posed a hazard to navigation. While initially registering at 38 ft. (11.58 m) below the surface, a depth warranting possible removal, by October it had settled down an additional 2 ft. (0.61 m), providing enough clearance for deep draft vessels, and no further action was taken. Records show a request from a New York company for salvage rights in 1921, which was apparently received favorably by Navy leadership, but no official grant of rights has been found and the wreck remained undisturbed.

The Wreck Site

In the decades since the sinking, the wreck site has been impacted by both natural and human interactions, including large-scale unauthorized salvage operations and removal of small artifacts by divers. After 1921, San Diego lay largely out of public and Navy attention until the 1950s, when the Navy once again undertook to sell salvage rights to the wreck. In 1957, the rights were sold to a New York-based company for a three year period; however, by 1963 no salvage had been conducted and the wreck reverted back to the Navy. During that period, a large number of artifacts were removed from the site by divers investigating the wreck for the salvage company. Renewed local interest in the wreck, alongside a growing nationwide historic preservation movement, prompted the Navy to turn down future salvage offers.

As with all U.S. Navy sunken military craft whose title has not been divested, the wreck remained government property, requiring Navy authorization prior to any salvage efforts. However, the accessibility of the wreck site continued to attract illicit salvage efforts for several decades. In 1965, the port propeller was removed without approval and subsequently lost between the wreck and Staten Island when the cable towing it broke. In 1973, San Diego’s starboard propeller was found to have become disarticulated from the wreck and was lying on the seafloor. In 1974, a second unauthorized attempt to retrieve that propeller ended in disaster for another salvage group when their barge capsized and sank near the wreck.

In addition to salvage interest, the wreck became a popular dive site. Over the years, countless objects that remain government property have been removed from the site, to include ceramics, lanterns, ammunition, and personal effects. Due to a combination of recreational divers going to extremes to secure artifacts (at least six people have died diving on the site) and professional rivalries between dive boat operators, the Navy was prompted to revisit the site and pursue further action to protect San Diego and other Navy wrecks being exploited.

After reports of ordnance being recovered by recreational divers in 1992, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) established a 500-yard exclusion zone around the wreck. Once the ordnance issue was investigated by Navy’s Explosive Ordnance Mobile Unit Two, USCG came to an agreement with local dive boat operators to cease further salvage of ordnance, and the wreck was reopened.

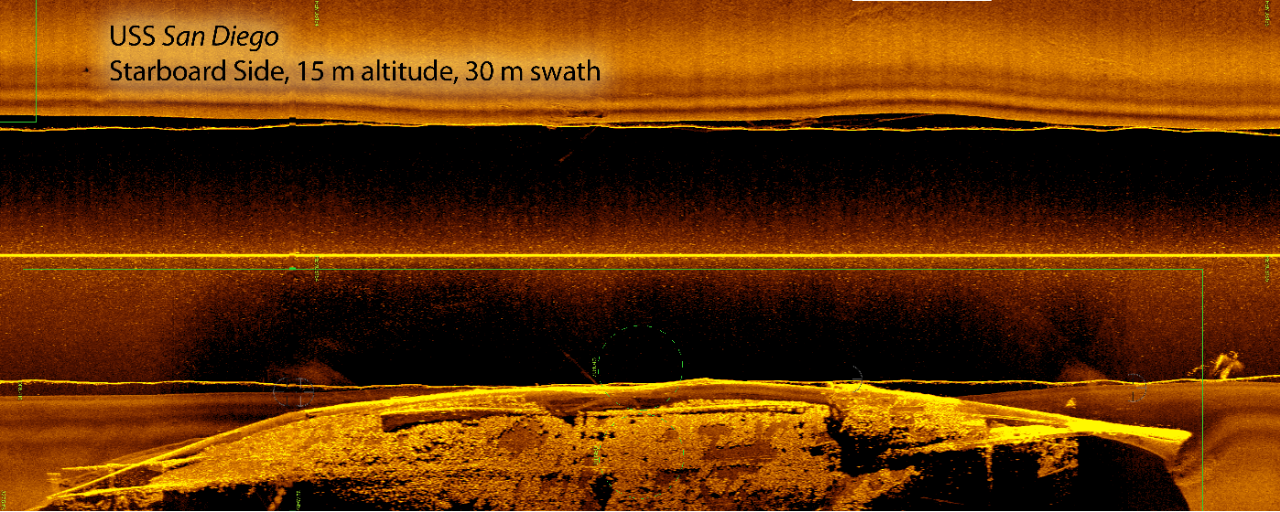

In order to address public safety and historic-preservation concerns, Ocean Sciences Institute was asked by the then Director of Naval History, Dr. William S. Dudley, to investigate the wreck under the direction of Underwater Archaeology Branch Head, Dr. Robert Neyland. Supported by divers from Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit Two (MDSU-2), fifty dives were conducted on the wreck site in June 1995. The survey found that the hull had shifted and the lean to the port side had increased to 15 degrees. In addition, Navy divers found that significant parts of the ship’s interior had deteriorated to the point that would make it extremely dangerous for recreational divers wishing to explore within. Navy EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) technicians also tested a projectile recovered from the wreck at Weapons Station Earle, and demonstrated that although underwater for several decades it was still able to detonate. Despite the multiple holes in the hull and collapse of the stern, Dr. James K. Orzech of the Ocean Sciences Institute, concluded that San Diego retained a moderate to high degree of structural integrity and that it had a similar rating for her archaeological integrity because its deteriorating interior discouraged unauthorized recovery of small artifacts held inside.

After the 1995 survey, the Navy worked with Dr. Orzech to nominate the site to the National Register of Historic Places. The nomination was approved and San Diego was added in 1998. While the wreck was always protected by law as government property, additional protections came into force in 2004 with the passage of the Sunken Military Craft Act (SMCA). The Act prohibits unauthorized disturbance of sunken military craft—both ship and aircraft—but authorizes the Secretary of the Navy to issue permits under federal regulations (32 CFR 767) allowing for the conduct of scientific research for archaeological, historical, or educational purposes. The permit program is managed by Naval History and Heritage Command’s Underwater Archaeology Branch.

USS San Diego Today

NHHC continues to manage the site as a sunken military craft, a war grave, and part of the U.S. Navy’s overall cultural resource management program. The command’s Underwater Archaeology & Conservation Laboratory curates a number of artifacts that were recovered without authorization and were later returned to Navy custody in recent years. The expertise of the conservators on staff is vital to the stabilization and long-term preservation of these fragile artifacts. In the lead-up to the 100th anniversary of San Diego’s sinking, NHHC archaeologists visited the site in 2016 and 2017 in conjunction with MDSU-2 dive training operations to assess the condition of the wreck. The data collected helped support a more comprehensive survey conducted in September 2017 in partnership with the University of Delaware, Naval Surface Warfare Center Carderock Division, the ONI Farragut Technical Center, and the U.S. Naval Academy. A further dive training operation supported by MDSU-2, the Military Sealift Command, and the U.S. Coast Guard allowed for an on-site commemoration to take place on July 19, 2018 in memory of the six Sailors lost on that day 100 years earlier.

As the only major warship lost by the United States during World War I, San Diego remains historically significant. It marks a transitional stage in naval architecture and tactics, bridging the period of early industrial iron ships and the later steel ships designed to maximize the advantages of steam-turbine technology. The site also serves as a stark reminder of how close enemy action came to the American coast during the war and serves as the final resting place of the six Sailors who lost their lives in the service of their country.

(For Further Reading:

Navy Commemorates 100th Anniversary of the Loss of USS San Diego—Story on the 2018 commemoration

USS San Diego 2017 Survey Field Report—Direct download (11.7 MB) of technical report summarizing the 2017 USS San Diego field survey

Dictionary of Amercian Naval Fighting Ships—Operational history, under California II (Armored Cruiser No.6)

Artifact collection page—Images of conserved artifacts in the NHHC UA collection

U-Boats in the Atlantic—Battle of the Atlantic, Chapter III German Intelligence on Allied Conveys in the Atlantic

Timeline of Events:

| 28 April 1904 | Ship is launched by Union Iron Works at San Francisco, California |

| 1 August 1907 | First commission under Capt. Thomas S. Phelps as USS California |

| March 1912 | Reassigned to the Asiatic station, visits Philippines, China, Japan |

| August 1912 | Sails to Nicaragua during political upheaval to monitor situation |

| 1 September 1914 | Renamed USS San Diego, designated flagship of Pacific Fleet |

| 21 January 1915 | San Diego suffers an explosion in her No. 1 fire room, killing five sailors and injuring seven more. Ensign Robert Webster Cary and Fireman Second Class Telesforo Trinidad are awarded Medals of Honor for their actions in getting crewmates out of danger. |

| 15 November 1915 | Rescues 48 passengers from the sinking SS Fort Bragg |

| 6 April 1917 | United States enters World War I. |

| 5 May 1917 | Adm. William F. Fullham designates San Diego as his flagship of Patrol Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet |

| 17 July 1917 | Assigned to U.S. Atlantic Fleet Cruiser Force. |

| 13 November 1917 | San Diego begins first voyage to France to escort Troop Convoy Group Eight. |

| 22 December 1917 | Enters dry-dock at New York Navy Yard for repairs and stripping of all her 14 6-inch guns in order to arm merchant ships. |

| 19 July1918 | San Diego sinks off the coast of New York. Damage is determined to be either from a mine or torpedo from an enemy U-boat. |

| 26 July 1918 | Tug Passaic (YT-20) conducts soundings on the wreck and determines it is a possible obstruction to shipping. A second sounding in October shows ship has settled 2 ft. (0.61 m) and is no longer a navigational hazard. |

| October 1957 | Sale of wreck to salvage firm for a 3-year contract “for scrapping purposes only.” Later, Navy extends contract until 1963. |

| 28 June 1963 | Ownership of San Diego reverts to Navy after salvage company fails to fulfill contract. |

| 1960s–1980s | Unauthorized salvage and removal of small artifacts. |

| 14-15 October 1992 | U.S. Coast Guard establishes an exclusion zone around San Diego wreck due to reports of ordnance salvage. Lifted the next day after investigation and report by Navy Explosive Ordnance Mobile Unit 2. |

| June 1995 | U. S. Navy conducts comprehensive baseline survey of site. |

| February 1997 | Judge dismisses 1995 lawsuit contesting Navy’s ownership of the wreck and its associated artifacts (Undersea Adventures, Inc. vs. USS San Diego). |

| 17 February 1998 | San Diego added to the National Register of Historic Places. |

| 19 July 2018 | 100th anniversary of USS San Diego ’s sinking. |