A Surgeon's Kit from the War of 1812

A Collection of Medical Implements from Commodore Joshua Barney's Chesapeake Flotilla

Below the waters of the Patuxent River, Maryland, only 16 miles from Washington, DC, lay the well-preserved remains of ship, scuttled to prevent capture by the British as they advanced on the nation’s capital in the summer of 1814. It was part of Joshua Barney’s Chesapeake Flotilla, a group of 13 to 15 oared gunboats and its flagship Scorpion. The wreck, initially excavated in 1980 under the direction of Donald Shomette, was found to contain a group of medical instruments and accessories, indicating that it housed the flotilla’s hospital facilities.

The flotilla, a force of nearly one thousand men, was attended by one surgeon, Dr. Thomas Hamilton, and up to two surgeon’s mates, Anthony C. Thompson and John W. Peaco. Hamilton and his men were expected to care for all aspects of the men’s health, including illness, wounds from accident or battle, and dental problems. Surgeon, internist, dentist, and pharmacist, the naval surgeon was additionally challenged by performing his duties in dark, cramped quarters subject to the unpredictable movements of the rolling seas. The objects found in the shipwreck reflect many of the surgeon’s activities.

Surgical Instruments

When the Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, sent Dr. Hamilton to Commodore Barney, he also sent along a medicine chest and surgical instruments taken from the blockaded sloop of war Ontario with strict orders to preserve them “in perfect order to be returned to the ship when prepared for service.” While circumstances prevented Barney from complying with his orders, correspondence from after the sinking indicates that one batch of instruments, specialized for amputation and trepanning, was saved by a civilian captain traveling with the flotilla. The fact that they were not left behind, combined with the subsequent effort the Navy made to recover them, attests to the value placed on these life-saving instruments. As most of them were made in Britain, the enemy in the current conflict, replacements were particularly difficult to acquire.

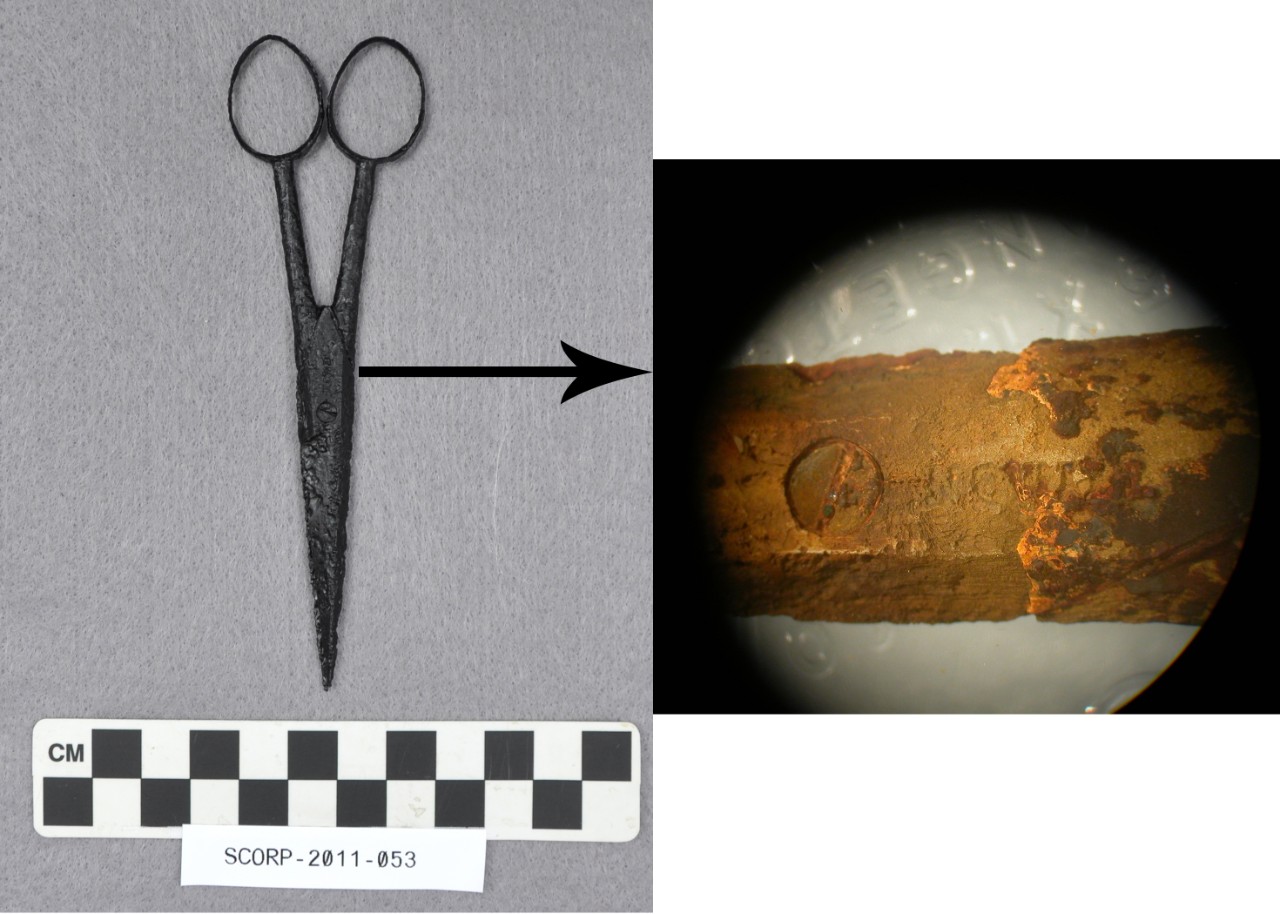

The surgical instruments recovered from the wreck included many essential components of a battlefield surgeon’s toolkit, such as specialized forceps with cupped ends for extracting bullets, several scalpels with folding handles, surgical scissors, and an instrument known as a director or guide. The director consisted of a tapered shaft, several inches long, with a groove down one side, with a small scoop at the other end. This was an important tool for treating wounds, as it could be used as a probe to locate foreign objects, as well as a guide for directing the scalpel or other instrument to the proper location while also protecting delicate nerves or blood vessels from being cut accidentally; the scoop end was used to remove debris from the wound, but also acted as a balance point for the surgeon’s hand.

Several of the instruments, including both pairs of scissors, were marked with the name Nowill, representing the firm of Hague and Nowill, makers of surgical instruments based in Sheffield, England. This region of England was widely known for its excellent quality steel and was a center of production for bladed implements. Several other pieces were marked with Evans and a crown, for John Evans and Company of London, who supplied surgical instruments to the Royal Navy for period starting around 1812. Despite the hostilities, the U.S. Navy may have found a way to purchase these instruments through commercial channels, but it is possible they were taken from a captured British ship earlier in the war.

Pharmaceutical Supplies

Naval surgeons were expected to act as their own pharmacists. They were provided a range of standards ingredients and had to mix up the appropriate formulas and dosages as needed. Typical supply lists could contain well over 50 different compounds, from the familiar, such opium, camphor and turpentine (oleum terebinthinae), to the unexpected, including rhubarb, digitalis, and nitric acid. Many ingredients were stored in small, clear-glass medicine bottles, of which nine were recovered from the site, some still sealed with their original corks. Two flat-bladed spatulas for mixing ingredients were also recovered, along with the head of a pestle and a fragment of a pill tile – a flat, glaze ceramic square which provided a strong, impermeable surface for mixing medicines that could be easily cleaned of all residue to prevent contamination of future mixtures.

Dental Instruments

By far the most intimidating of the instruments recovered were the tooth key and forceps, used for removing diseased or broken teeth. While no doubt an unpleasant experience, the alternative of leaving the tooth alone could lead to a systemic infection that could prove not just painful, but debilitating or even fatal. While dental fillings were starting to become available to those with money and access, this generally fell outside the naval surgeon’s training, and when at sea there was little choice when infection arose but full extraction of the tooth.

Dental health at this period was undermined by America’s access to sugar, which often led to more severe levels of tooth decay than their European counterparts. In addition to chewing food, teeth were employed as tools, to tear fabric or hold objects while the hands were occupied, leading to accidental breakage or wear. Some pipe smokers even wore half-moon-shaped grooves in their teeth from gripping the pipe stem, sometimes deep enough to expose the nerve.

Several other specialized instruments were part of the typical dental kit at the time, but were not recovered from the wreck, suggesting a few might remain on site.

Other Related Items

In the same area with the medical instruments were found a number of other items vital to the running of a hospital. A ceramic chamber pot attests to the needs of the men being treated in the space. An inkwell is a reminder that a detailed journal of the patients and their treatments was kept by all naval surgeons, though not many from that period survive. The surgeon was charged also with accounting for all medicines and equipment used and requisitioning new supplies when needed. Several glazed redware bowls were also found in association with the medicine bottles, and have thus been dubbed “apothecary bowls.” While not specialized in form, they likely had medical uses, from mixing liquid medications to collecting blood or other fluid from a wound.

Conclusion

The duty of a naval surgeon and his staff was challenging, demanding, and dangerous. Dr. Hamilton was present on the battlefield with Joshua Barney at the Battle of Bladensburg, and treated the wounded commodore on the battlefield. After spending a year treating men for a range of fevers and internal disorders attributed to the pestilential environment of the Maryland river, Hamilton was himself afflicted with a recurring and debilitating fever in December 1814 that so impacted his health and ability to continue his practice after the war, that he applied for a pension in 1818.

Surgeon’s mate Peaco, who joined the flotilla in May 1814, sought further service with the Navy after the war and, with Hamilton’s recommendation, served aboard the frigate Java under command of Oliver Hazard Perry in the Mediterranean. He was promoted to surgeon in 1824 and died of a fever in 1827 while serving as U.S. Agent in Africa as part of the government’s efforts to suppress the slave trade.

Further Reading

U.S.S. Scorpion Artifact Vignette

Archaeology of the Chesapeake Flotilla

Letters Pertaining to an Outbreak of Yellow Fever on Thompson’s Island (Key West), FL, including the loss of most of the medical staff (p. 1112 and following)