Navy's Historic Aircraft Wrecks in Lake Michigan

Aircraft Losses from Carrier Operations During World War II

In August 1942, the U.S. Navy commissioned USS Wolverine (IX-64) as its first in-land aircraft carrier. The Navy added USS Sable (IX-81) on May 8, 1943. Neither vessel ever left the Great Lakes. The Navy thought the Lake Michigan area, because it was so far inland, was an ideal training ground for its carrier pilots.1 Although limited training occurred in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay, the majority of carrier qualifications during World War II occurred from the decks of Sable and Wolverine.2

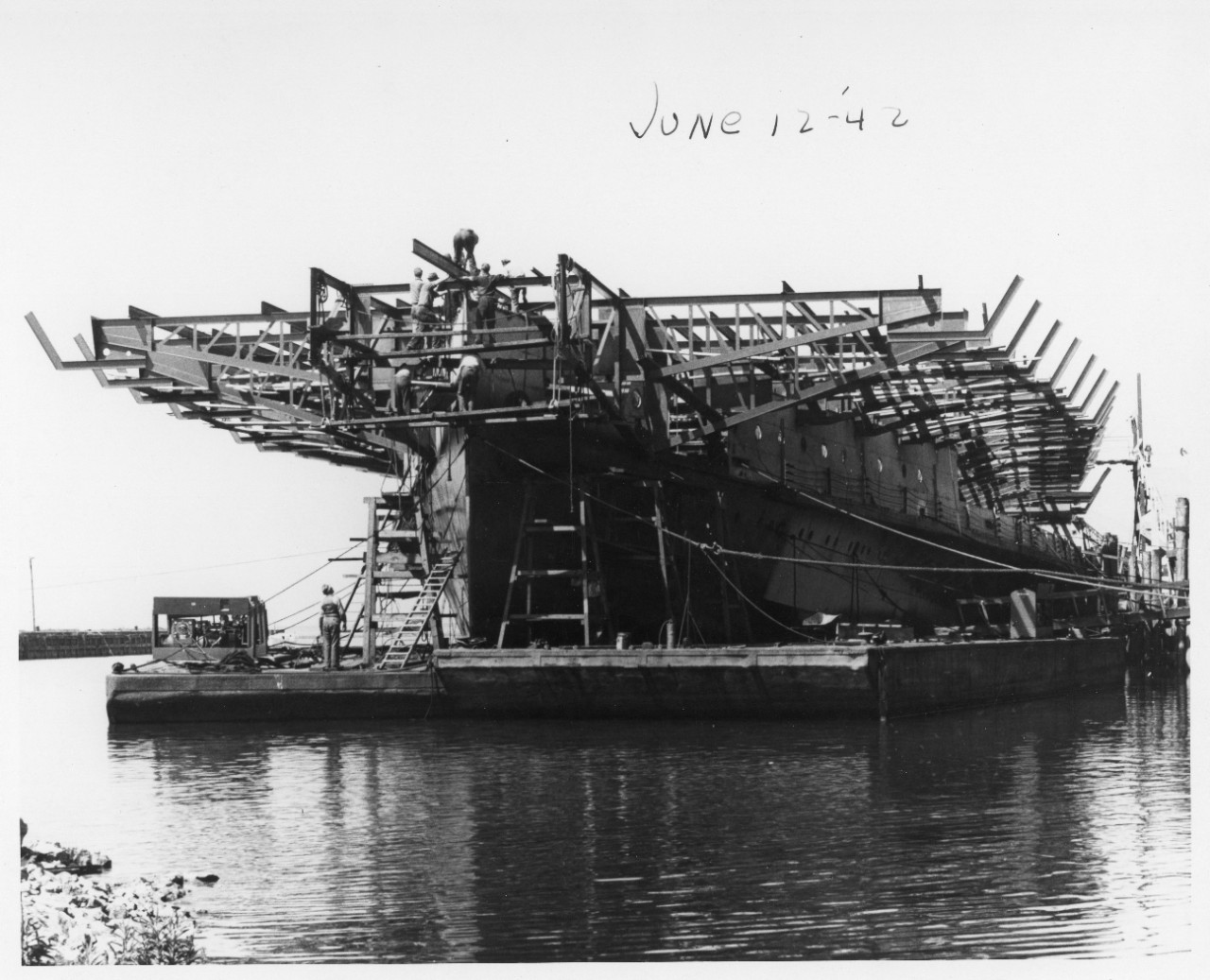

The Cleveland and Buffalo Transit Company launched Wolverine in 1913 under the name Seeandbee. At its launch it was the world’s largest side-wheel passenger steamer on inland waterways. Seeandbee represented the best of Edwardian passenger vessels. Its opulence and comfort were second to none on the lakes. Sable, launched as Greater Buffalo in 1924, eclipsed Seeandbee in size, thereby replacing it as the world’s largest side-wheel passenger steamer.3

The U.S. Navy acquired both vessels shortly before World War II. The Navy converted them from passenger steamers into aircraft carriers for carrier operations training of Navy and Marine Corps pilots. Both vessels retained their coal driven, side-wheel, propulsion systems, making them the only side-wheel propelled carriers in the U.S. Navy. Although large, their 550’ decks were smaller than the Navy’s ocean going carriers and as such, provided excellent training platforms; if a pilot could make it on this deck, he could make it on any other deck in the Navy’s fleet.4

Wolverine launched its first aircraft on August 25, 1942 and served as a training platform until November 11, 1945 when both vessels were decommissioned. Sable qualified its first two pilots on May 29, 1943. Both carriers were scrapped sometime after World War II.5 On October 21, 1942, Ensign F. M. Cooper, piloting an F4F-3 Wildcat, spun into the water after takeoff from Wolverine. The plane sank with Cooper into 85' of water. Neither his body nor the plane was ever recovered. This was the first of many accidents to occur on board these ships.6

As training vessels, mishaps, accidents, crashes, and losses from the decks were expected. Between 1942 and 1945, the years of the carriers’ operations, there were 128 losses and over 200 accidents. Although the majority of losses resulted in only minor injuries, a total of eight pilots were killed. These numbers seem significant until it is considered that during that time over 120,000 successful landings took place, and an estimated 15,000 pilots qualified.7 The training program, in this light, was a huge success.

During the war, six of the crashed aircraft were recovered. These were mainly shallow water recoveries that did not require extensive time or specialized equipment.8 Many have postulated that damaged planes were pitched overboard as had been the case in wartime theatres like the Pacific. There is no evidence that any damaged planes were tossed overboard, but rather, there is sufficient evidence that reveals that damaged planes were returned to the dock or picked up while the ships were still on missions and returned for repair.9 Because the carriers were not isolated as they were in the Pacific theatre and had repair facilities available, damaged aircraft were saved whenever possible. Occasionally this meant retrieval from underwater.

The Navy used various aircraft for these training qualifications. Through ship’s logs and Aircraft Accident Cards we know that of the aircraft listed as lost were 41 TBM/TBF Avengers, one F4U Corsair, 38 SBD Dauntless, four F6F Hellcats, 17 SNJ Texans, two SB2U Vindicators, 37 FM/F4F Wildcats and three experimental drones known as TDNs.10 Several of the aircraft used for training had prior military history. Some served in Pacific campaigns, others in North Africa. Very few were new planes. Taken individually, the aircraft lost in Lake Michigan have historical value for battle service.11 However, even though many never saw battle they are still valuable as representatives of their type, or for their rarity today. Taken as a whole, the entire assemblage is significant for their service in carrier qualifications training in Lake Michigan. This history is important to the Navy, to the states surrounding southern Lake Michigan and to the nation.

The aircraft assemblage in Lake Michigan represents the largest and best-preserved group of U.S. Navy sunken historic aircraft in the world. From a historical perspective, the assemblage provides a wealth of knowledge about the history of naval aviation. Individually they are physical pieces of our past linked to significant people and events. Vast amounts of information can be gleaned from and memorialized through these special objects. Artifacts lost in the cold, fresh waters of Lake Michigan usually exhibit excellent preservation characteristics. Many of the aircraft in this assemblage have been found in good condition, tires inflated, parachutes preserved, leather seats maintained, and engine crankcases full of oil. Often paint schemes are well preserved, allowing for easier identification.

To better manage this assemblage, the Naval Historical Center (now the Naval History and Heritage Command) conducted a limited side-scan sonar survey in May 2004, to relocate several examples in the assemblage. The survey targeted five examples based on several variables: the type of location information available, the site’s proximity to the staging area, and the level of historic significance or threat level. The weeklong survey located many interesting targets for further study. Although not an aircraft wreck, of particular interest could be the remains of the World War I German submarineUC-97, sunk by the U.S. Navy in 1921 as a requirement of the Treaty of Versailles.12

With such a large assemblage it would be ideal to use many different approaches to preservation, including in-situ wherever possible. The Naval History and Heritage Command works with the states that border southern Lake Michigan to find ways to make the most of this assemblage. Discussions continue on ways to manage the sites for the benefit of the American public, the Navy, and the local populace.

Notes:

1. Navy Department. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Naval History Division, Washington, 1970, vol. VIII, p. 443, vol. VI, p. 217.

2. Based on research conducted by UA in Lake Michigan. The information contained came from numerous resources, but mainly consist of information from Aircraft Accident Reports (AAR), microfilm, Naval History and Heritage Command, Naval Warfare Division, Aviation History Branch, Washington, D.C., and deck log’s of Sable and Wolverine. Deck logs for USN Ships, archived at the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, RG 24.

3. Top Guns of 1943; Newell, Rob. “Cornfields and Carriers.” The Retired Officer Magazine. http://www.moaa.org/magazine/October2002/f_cornfields.asp 5-13-03.

4. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

5. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

6. Aircraft Accident Report for this incident, microfilm, Naval History and Heritage Command, Naval Warfare Division, Aviation History Branch, Washington, D.C., Wolverine decklog.

7. Based on database formatted research. The information contained in the database came from numerous resources, but mainly consist of information from AARs, and deck logs of Sable and Wolverine. Deck log’s for USN Ships, archived at the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, RG 24.

8. Ibid.

9. Ship’s decklogs.

10. Lake Michigan UA research.

11. Aircraft History Cards, microfilm, Naval History and Heritage Command, Naval Warfare Division, Aviation History Branch, Washington, DC.

12. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships; Letter from Captain J. Ashley Roach, JAGC to Stephen Lysaght, British Embassy, 13 April 1994.