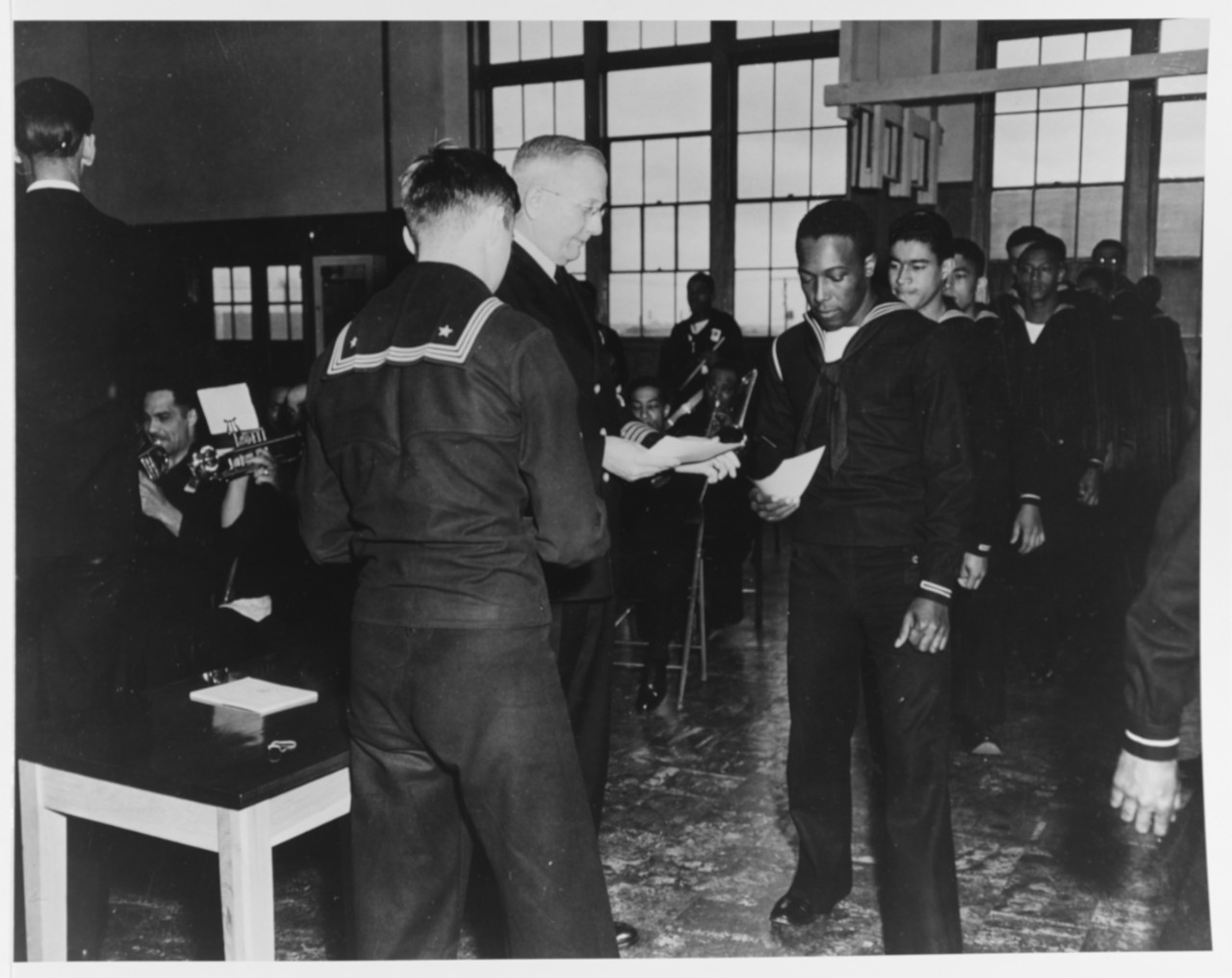

African Americans in General Service, 1942

(NOTE: The terms “African Americans” and “blacks” are used interchangeably.)

The Navy was racially integrated through 1865. Blacks served on the 700 ships in the Union Navy and eight of them received the Congressional Medal of Honor.1 After that period, the Navy reduced recruitment overall which decreased the number of blacks in the service. In the second half of the 19th century, the Navy adopted recruitment policies that were consistent with the racism, discrimination, and separation of the races practiced by law and custom in American society. The Klu Klux Klan and other racist individuals and groups terrorized and killed blacks and destroyed their property at will with no fear of being arrested. Southern communities implemented the black codes to “keep blacks in their place,” i.e., preventing more than three African Americans from congregating in public and giving them additional requirements to vote. The share-cropping system replaced slavery. The 1896 Supreme Court decision on Plessy v. Ferguson constitutionally sanctioned “Jim Crow” or separate-but-equal policies. There were so many lynchings of blacks that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) posted the number of victims at its New York City headquarters. Thus, before World War I, race relations in America were dismal with little hope for change. The Navy limited the ratings for which blacks could apply to coal heaver, messman, steward, and cook. Chief Gunner’s Mate John Henry Turpin, a survivor of the explosion aboard the battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor, was an exception. Most of the 10,000 African Americans in the Navy during World War I fought to make the world safe for democracy despite their own limited opportunities. There were no blacks in the naval officer corps. Only a small number of them remained in the Navy during the interwar period. In fact, the Navy did not recruit African Americans for general service after 1922. From about 1919 to 1932, the Navy relied on Filipinos to serve in the ratings traditionally held by blacks. The changing status of the Philippines led the Navy to resume recruitment of African Americans.2

Black leaders advocated for desegregation of the armed forces and racial equality in the military for some time. A number of them met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the fall of 1941 to discuss the matter. In response to pressure from the NAACP and other black organizations, Roosevelt suggested that one step toward integration would be to place black bands on battleships to facilitate race relations among the crew. He also called for 5,000 blacks to be recruited to serve on small harbor craft and at naval shore establishments in the Caribbean. Black leaders’ opposition to the Navy’s racial policies persuaded Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to select a committee composed of naval and Marine Corps officers, and Addison Walker, a civilian special assistant to Ralph Bard, Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Knox asked them to determine if there was evidence of discrimination in the Navy and Marine Corps based on race, creed, color, or national origin and to recommend changes. The committee concluded that allowing blacks to serve in other billets would disrupt naval operations and thus, no policy changes were needed. Addison Walker disagreed, maintaining that blacks could be assigned to small craft and trained by white officers. He argued that racial tension was an obstacle to naval efficiency. Thus, the committee produced one report, but Walker wrote another. He also resigned his position as a special assistant to Bard.3

Black leaders, including the president of the NAACP, remained determined to change the Navy’s recruitment policies regarding blacks and presented their arguments to President Roosevelt. He passed them on to the newly established Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). Roosevelt’s decision to do so proved ironic. First, the FEPC resulted from the 100,000-strong march on Washington proposed by A. Philip Randolph, president of the black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to oppose the discriminatory hiring practices of defense contractors and racism in the military. Second, as a civilian agency, the FEPC had no authority to establish or change racial policy in the military. Mark Etheridge, chairman of the FEPC, concluded that even if blacks were segregated they could perform duties outside of those traditionally assigned to them.4

Etheridge encouraged the President to ask Knox to determine what those jobs might be. In January 1942, Secretary Knox ordered the Navy’s General Board to devise a plan for the recruitment of 5,000 blacks and to suggest a wider variety of duties. The General Board was responsible for studying all aspects of naval policy and making recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy based on its observations. After meeting, the board concluded that blacks should be restricted to serving as messmen because there were few non-rated billets on patrol ships and integrating blacks and whites in non-rated billets on larger ships would cause friction and lower efficiency.5 The board also concluded that “if restricting [blacks] to the messman branch was discrimination, it was consistent with discriminatory practices against [blacks] and citizens of Asian descent throughout the United States.”6

The Board decided after at its second meeting in February 1942 to ask the Bureau of Navigation, responsible for personnel matters, to supply a list of stations and assignments for blacks that included service units throughout the naval shore establishments, yard craft, and other small craft employed in Naval District local defenses, composite Marine battalions, and construction battalions. After some discussion, Roosevelt instructed Knox to implement the necessary measures. Consequently, the Navy announced on 7 April 1942 that blacks would be enlisted in general service as well as the messman branch beginning 1 June 1942. On 1 February 1943, more than two thirds of the 26,909 African American Sailors were messmen.7

The Navy’s decision not to make maximum use of all available manpower resources 14 months into the war placed the burden of combat duties on white Sailors. How much more might the black Sailor have contributed if he had the opportunity to fill more ratings and to attain more leadership positions? However, there is no way to know if the war might have ended sooner, if fewer lives would have been lost, or how much more efficient the Navy might have been, had Knox assigned blacks according to their qualifications instead of their race.

________________

1 See African American Civil War Sailors projects on the National Park Service website for more information.

2 Lieutenant Dennis D. Nelson, The Integration of the Negro Into the United States Navy, 1776–1947, Second Printing (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1948), 25; “World War II Administrative History, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Negro in the Navy” #84, 3-4, hereafter WWIIAH #84; Philip T. Droting, Black Heroes in Our Nation’s History— A Tribute to Those Who Helped Shape America (New York: Cowles Book Company, Inc., 1969), 179–80.

3 Bernard C. Nalty, Strength for the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military (New York: Free Press, 1986, 1992), 185–86; Towsen Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley, Driven Patriot: The Life and Times of James Forrestal (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 181; WWIIAH #84, 3, 4.

4 WWIIAH #84, 5.

5 “Enlistment of men of the colored race other than messmen’s branch: transcript of hearings before the General Board of the Navy, 23 January 1942, 1–2, Ready Reference Files on blacks in the Navy, World War II, Navy Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard, Washington, DC; Annual Report of the Department of the Navy-Fiscal Year 1942, 9.

6 WWIIAH #84, 6.

7 Ibid., 5–9; Nalty, 188–89.

Suggested reading:

Regina T. Akers, “The integration of African Americans into the WAVES,” Master’s Thesis, Howard University, Washington, DC, 1993.

Richard E. Miller, The Messman Chronicles, African Americans in the U.S. Navy, 1932–1943 (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2004).

Bernard C. Nalty, Strength for the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military (New York: Free Press, 1986).

Bernard C. Nalty and Morris J. MacGregor, Blacks in the Military: Essential Documents (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Press, 1981).

Dennis D. Nelson, The Integration of the Negro Into the United States Navy, 1776–1947 (New York: Farrar and Strauss, 1951).

“World War II Administrative History, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Negro in the Navy, #84.”

—Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command, 23 March 2017