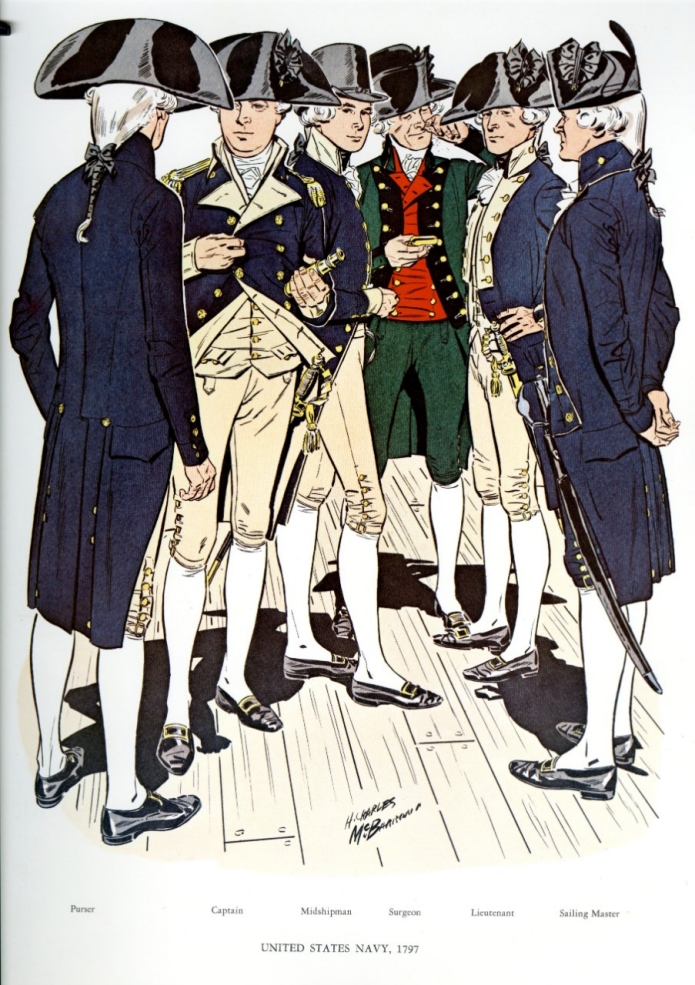

Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1797

The first uniform instruction for the United States Navy was issued by Secretary of War, James McHenry, on 24 August 1797 in order to provide a distinctive dress for the officers who would command the first ships of the Federal Navy. When the Federal Government was organized in 1789, there were no warships of the Revolution still in service. The immediate problems were internal, and the protection of the western frontiers. When the War Department was created in August 1789, the Secretary was directed to perform all functions relative to both the land and naval forces.

Conditions soon changed, for shortly after the close of the Revolution American ships were again sailing the high seas, as they had before 1775 when they carried a large portion of British trade. Now one thing was lacking, the protection of the British flag, backed up by the Royal Navy! The Barbary Powers, long held in check by the British Navy, considered American shipping fair game, capturing ships and enslaving their crews. While the need for some force afloat to protect American commerce was recognized, the new Government considered it would be impossible to finance a navy and support an army for the protection of the frontiers and to maintain internal order. The situation worsened, and in March 1794, Congress took the first step to provide “… a Naval Armament.” The Act contained a proviso that if peace were secured with Algiers, the most aggressive of the Barbary Powers, no ships were to be built.

The Act made provision for six frigates and established the rank, pay and allowances of officers. Provision was made for three classes of non-combatant or civil officers (today’s staff officers)—surgeons, chaplains and pursers (Supply Officers).

Before any real progress had been made in the construction of the frigates, peace was concluded with Algiers. Congress did permit the completion of three ships whose construction was well along. Trouble with the other Barbary States, who resented the tribute paid Algiers, and attacks by privateers of the new French Republic, made it mandatory that the United States have some force afloat. Congress in 1797 authorized the manning of the three frigates nearing completion, the Constitution, United States and Constellation.

Although Secretary McHenry’s letter of 24 August 1797, forwarding the uniform instructions to Captain John Barry, the Senior Captain of the Navy, stated the purpose of the order was to secure “…a perfect uniformity of dress …”, the instruction did not provide a uniform as we understand the term today, that is clothing of one basic pattern with devices to indicate rank and specialties. Instead the cut of the coat, or the color, indicated rank and corps. The uniform was not the blue and red specified by the Continental Congress in 1776, or the more elaborate blue and white uniform adopted by certain officers in 1777, but blue and buff, similar to that worn by the Army in 1797, and reminiscent of the American Revolution. As is to he noted from the painting, a captain’s coat had long buff lapels with nine buttons on each lapel, while a lieutenant’s coat had short lapels with six buttons on them and three buttons below the right lapel with three buttonholes on the left. A captain wore two epaulets and a lieutenant, the only other commissioned combatant officer, wore an epaulet on the right shoulder only. Another indication of a captain’s rank was the use of four buttons on the cuffs, at the pocket flaps and at the vest pockets. A lieutenant had but three buttons at the pockets and at the cuffs and none on the vest at the pockets. This method of indicating rank by button lasted many years in the United States Navy.

The other seagoing officers who could command at sea in emergency were the sailing masters and midshipmen, both warrant officers. A master’s coat was similar to that of a captain, but with blue lapels, edged with buff. The coat for midshipmen was of a different cut from that of their superiors, “Plain frock coat of blue, lined and edged with buff, without lapels, a standing collar of buff, and plain buff cuffs.…” All combatant officers wore buff rests and breeches, except sailing masters who wore blue.

In 1797, the only commissioned non-combatant officers were surgeons, surgeon’s mates and chaplains. No uniform was prescribed for a chaplain, so he was clothed in the usual civilian attire of his faith. It would be years before chaplains would be able to wear a uniform which would indicate that they were part of the Naval Establishment. In prescribing the clothing of surgeons, the order made it plain that they were not Line officers. While a surgeon’s coat was cut like that of a captain, it was of green cloth with black velvet collar, lapels and cuffs. The double-breasted vest was red and the breeches, green. However, a surgeon did have two rows of nine buttons on the lapels, a practice which, with some exceptions, would indicate for many years, commissioned status. On the cuffs there were three buttons but none at the pocket flaps. Surgeon’s mates were ordered to wear a coat like that of lieutenants but green with black facings. Pursers, warrant officers in 1797, wore the blue and buff of the combatant officers, but their coats were of the plain frock variety without lapels. Although the purser’s coat was of civilian cut, the blue and buff indicated military status.

The order did not specify an undress uniform except that all officers were to wear cocked hats, those of captains and lieutenants to be lace trimmed in full dress. Midshipmen wore cocked hats in full dress, and the round hat of the period in undress, as shown.

The 1797 order did not mention clothing for petty officers or seamen and it would not be until 1841 that an official uniform instruction would cover enlisted personnel. There was a degree of uniformity, however, for the usual dress of seamen was made up of a short jacket, shirt, vest, long trousers and a black low crowned hat. Soon after the organization of the United States Navy, clothing for the men was bought on contract, stored at the navy yards, and carried aboard ship under the control of the purser. When men made their own clothing, they were directed to follow the pattern of the clothing in “slop stores,” that is, “small stores” aboard ship.