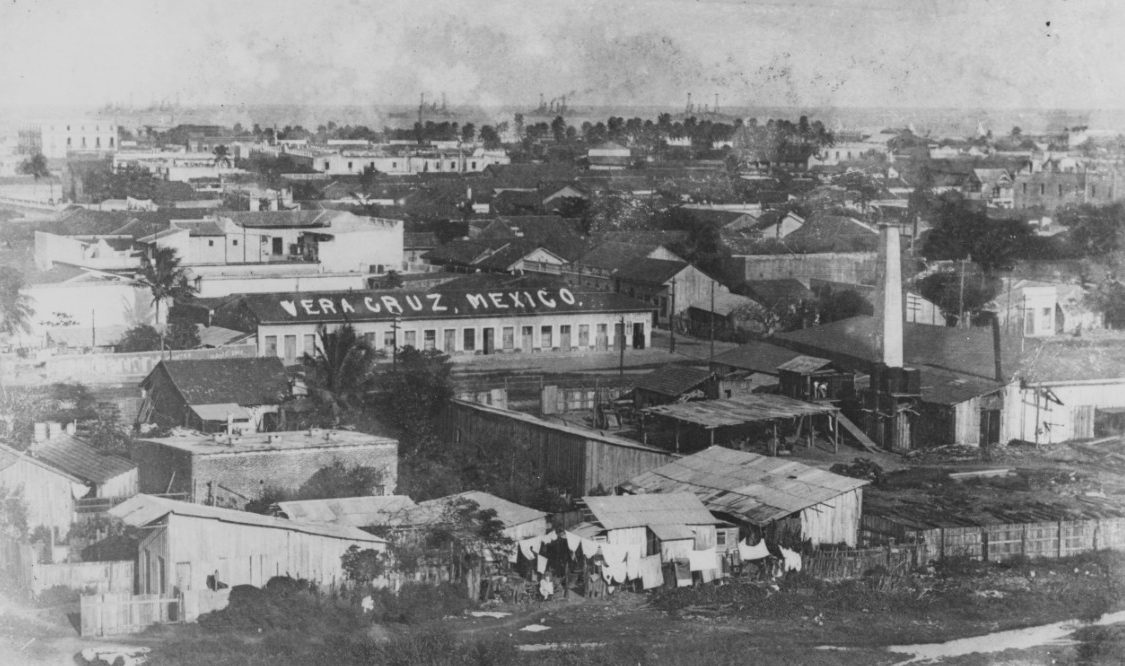

Aerial Reconnaissance at Veracruz, Mexico, April–June 1914

Trouble had been brewing in Mexico since the coup of General Victoriano Huerta in February 1913. Newly elected President of the United States Woodrow Wilson had no wish to recognize an authoritarian regime. The political unrest within Mexico contributed to rising tension between the two leaders and their respective countries. In October, President Wilson ordered Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, to position a squadron off the Gulf Coast of Mexico to intercept any arms shipments and to protect American lives in case an escalation of tensions necessitated evacuation.

On 9 April 1914, USS Dolphin anchored off Tampico, Mexico, to buy gasoline. Unfortunately, the warehouse at which they attempted to make their purchase had been declared off-limits to foreigners. The subsequent arrest of the sailors was not allowed to pass unnoticed—despite their immediate release with the apologies of General Morelos Zaragoza. Admiral Henry T. Mayo, in command of the 5th Division of the Atlantic fleet off the coast of Tampico, wanted more than an apology. Without the prior approval of the President, Mayo demanded further contrition in the form of a full 21-gun salute to the American flag. Although frustrated with Mayo’s initiative, Wilson did not contradict his admiral.

Zaragoza refused Mayo’s demands. Huerta subsequently refused to admit any wrongdoing and offered a compromise—a salute of both flags by both countries at the same time. Wilson refused and issued his own ultimatum—salute the flag before 1800 on 19 April, or risk retaliation of the U.S. armed forces. When Huerta ignored this warning, Wilson realized that diplomatic negotiations had failed. He asked Congress to approve a de facto invasion of Mexico to stop an arms shipment en route to Mexico. Three days later, American sailors and marines prepared to disembark at Veracruz. Tampico remained the focal point of this “small war,” but Veracruz was the chief port on the eastern coast of Mexico.

____________________________________________________________________

Almost as soon as naval aviators began to experiment with airplanes in 1911, they began to document the experience with compact cameras. In February 1913, Lieutenant John H. Towers and a detachment from Annapolis reported from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, on experiments conducted in support of the fleet. He wrote that they had “‘obtained some good photographs from the boats [seaplanes] at heights up to 1,000 feet.’”[1] The success of these trials contributed to the decision to send naval aviators into action after the Tampico incident in April 1914. The operations in Veracruz gave naval aviators an opportunity to utilize what they had learned since 1911 under wartime conditions.

The commissioned officers of the Aviation Corps, at the Naval Aeronautic Station, Pensacola, Florida, March 1914, including (left to right): Lt. Victor D. Herbster; Lt. William M. McIlvain, USMC; Lt. j.g. Patrick N. L. Bellinger; Lt. j.g. Richard C. Saufley; Lt. John H. Towers; Lt. Cdr. Henry C. Mustin; Lt. Bernard L. Smith, USMC; Ensign Godfrey DeC. Chevalier; Ensign Melvin L. Stolz. (NHHC, NH-119832.)

The pre-dreadnought USS Mississippi (Battleship No. 23) was taken out of reserve in late 1913 and became the first U.S. Navy ship converted to a seaplane tender. Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin became its first executive officer and acting captain as of 31 December 1913. After Secretary of Navy Josephus Daniels ordered the establishment of the first permanent naval air station, Mustin received orders to report to Pensacola from the new administrator for naval aeronautics, Captain Mark L. Bristol. Mississippi would serve as the station’s ship, and Mustin would be its commanding officer.

Lieutenant Towers also received orders to Pensacola to serve as an instructor for new naval aviators. The new station and its flight school had only been in operation for three months when they received orders to prepare for their first overseas mission.

On 20 April 1914, Towers received orders to take an aviation detachment to Tampico immediately. This detachment left Pensacola aboard USS Birmingham (Scout Cruiser No. 2) to join the Atlantic Fleet forces in Tampico, Mexico. First Lieutenant Bernard L. Smith, U.S. Marine Corps, and Ensign Godfrey Chevalier accompanied Towers. They selected three hydro-aeroplanes, including a C-5 (later redesignated AB-5) and an A-4 (AH-2), with double pontoon floats rather than landing wheels.

Lieutenant Patrick N. L. Bellinger worried that he would miss out on the action until new orders arrived, sending him and a second detachment to Veracruz aboard Mississippi. [2] Tampico remained the focal point of the action, but a German-registered ship, SS Ypiranga, was headed for Veracruz carrying an arms shipment intended for Huerta’s forces. Mustin remained in command of Mississippi, and Bellinger was responsible for the planes.[3] After the departure of the first detachment, the last two operational planes were a Curtiss C-3 (AH-3) hydro-aeroplane and a Model F C-3 (AB-3) flying boat. The most-experienced pilots had gone to Tampico. Bellinger was the only one of the remaining pilots qualified to fly. Lieutenant Richard C. Saufley, Ensign Melvin Stolz, and Ensign Walter D. LaMont were all student aviators selected to go to Veracruz as assistant pilots. They also had mechanics, including H. H. Wiegand, Einar Boydler, Harry E. Adams, and Augustus A. Bressman.

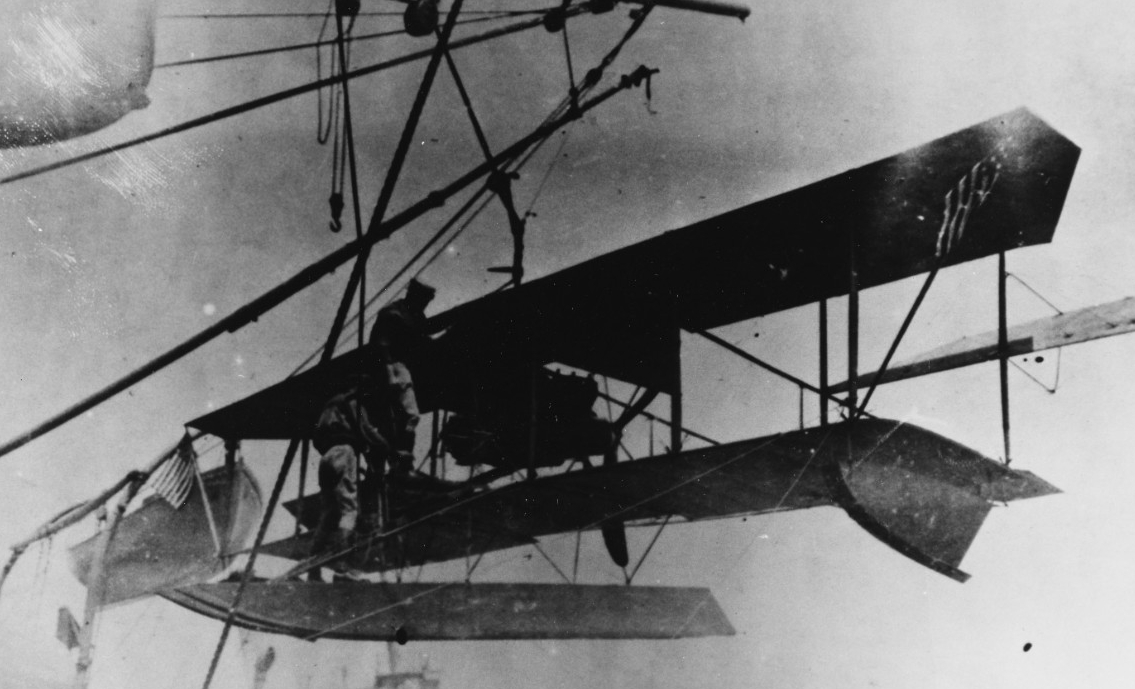

Mississippi was not an aircraft carrier, so the aviators required a means to lower the plane off the deck of the ship into the water. En route to Veracruz, Mustin and Bellinger worked with their team to rig an extension boom to lower the plane off the deck of the ship and into the water upon their arrival. Bellinger also prepared a means to quickly convert the A-3 to a landplane. He figured that the beach would make “a good runway for a landplane,” so they replaced the pontoons of the A-3 with wheels. They were ready to lower a plane over the side and get in the air within minutes of their arrival in Mexico. [4]

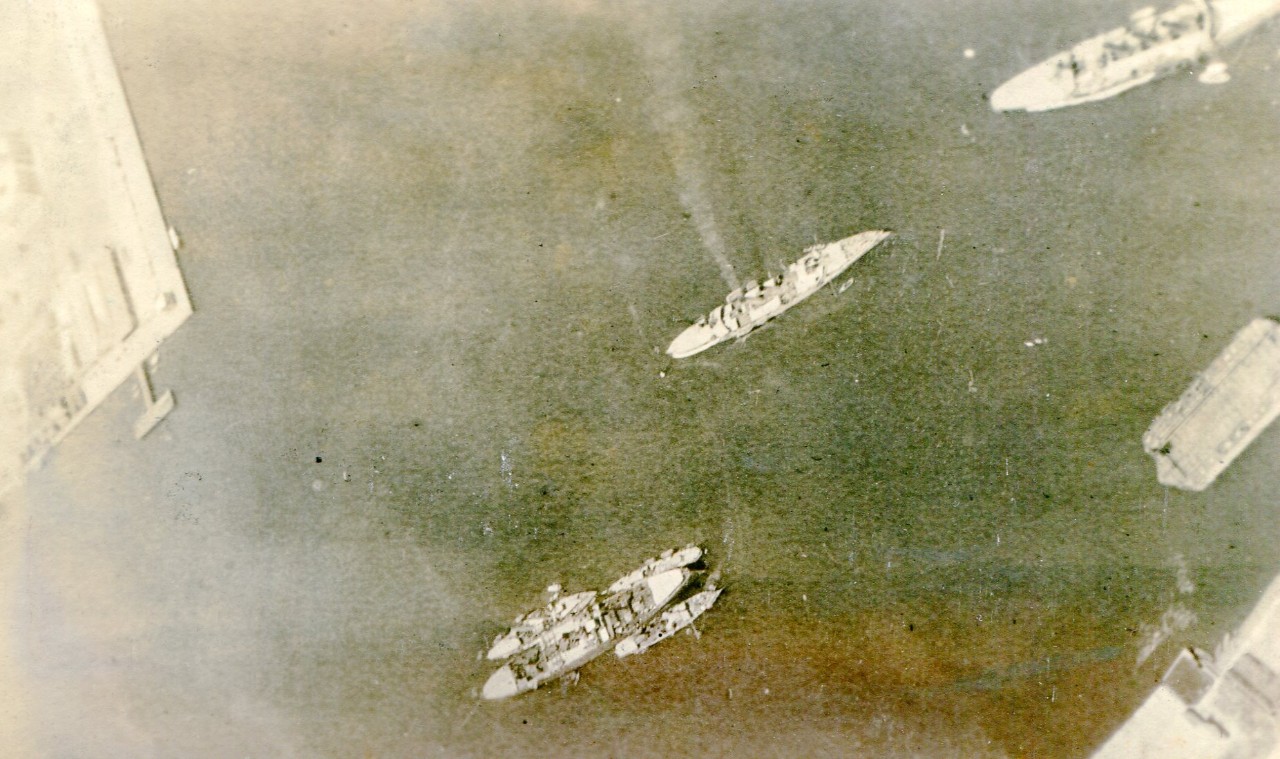

On the morning after their arrival on 24 April, Mustin reported to Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, the division commander in charge of the naval forces at Veracruz. Fletcher directed Mustin to conduct an aerial sweep of the harbor for mines. He also advised Mustin to coordinate with Colonel John A. Lejeune, U.S. Marine Corps, who was in command of the new Marine Advance Base Force.[5]

On 25 April at 10:44 a.m., Bellinger prepared the C-3 for a solo flight. After an initial inspection of harbor for mines, Bellinger returned to the ship, where he took on Ensign Melvin Stolz as an observer.[6] Then, they flew over the city of Veracruz.

The next day, Bellinger identified a location on the beach to establish a camp on land. On 28 April, Bellinger flew a scouting flight in the Curtiss flying boat (AB-3) over the coastline, accompanied by LaMont. The photographs taken on this flight represented the first recorded aerial photographs taken amid wartime conditions.[7]

The aviation detachment remained in camp on the beach coordinating with the Marine Corps and the Army. The planes remained under the operational control of the Navy. Their mission to Veracruz represented the first time that aviation units had functioned in support of land forces under wartime conditions.

On 2 May, Bellinger and Saufley flew inland on their third flight in response to news that the U.S. Marines at El Tejar, nine miles from Veracruz, were under attack. They could detect no enemy movement from the air, but their flight was the first reconnaissance mission under wartime conditions. [8]

While they searched for enemy soldiers, Lieutenant Richard C. Saufley made charts in flight and used them to create maps showing the terrain of the surrounding countryside for the American joint force. Admiral Fletcher, in command of the blockading squadron, complimented Saufley’s work.[9]

On 6 May, Bellinger and Saufley had descended to an altitude of approximately 150 feet, when they were apparently hit by rifle fire.[10] They did not detect the shots as they passed over a small village along the river, but Bellinger assumed this village to be the most likely the source of any animosity toward their presence.[11] This is the first known instance of hostile fire striking a U.S. plane.

On 8 May, Captain Henry L. Newbold, of the 4th Field Artillery, accompanied Bellinger, circling over land beyond U.S. outposts to collect information for the U.S. Army.[12]

At Tampico, Towers had orders not to fly.[13] On 24 May, the aviators sent to Tampico were redirected to Veracruz, approximately 300 miles south. Upon their arrival the next day, Towers assumed the role of senior aviator at Veracruz.[14]

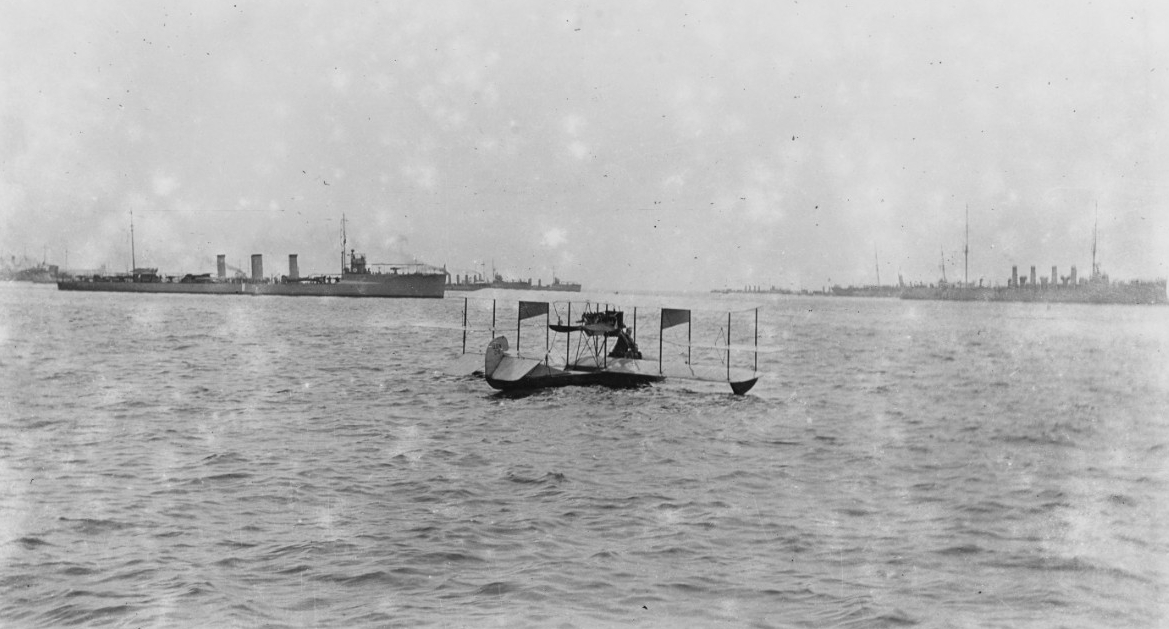

In May 1914, a U.S. Navy aeroplane flies over the water off the coast of Mexico between Minnesota (Battleship No. 22) (left) and Birmingham (Scout Cruiser No. 2) (right). (NARA, 19-VC-Y.)

On 24 May, Bellinger performed another scouting flight at the request of Lejeune. He flew inland to Punta Garda to search for Mexican troops. He located them, and the U.S. Marines in the area heard the Mexicans firing on the plane, even as it passed over at an altitude of 3,000 feet. Bellinger came to the conclusion that “the Mexicans let go at the plane any time they thought there was a chance of making a hit.”[15]

During the aviators’ time in Veracruz, Bellinger escorted a number of the war correspondents into the air. Jimmy Hare, a photographer, was also among those who flew with Bellinger (Collier’s Weekly had hired writer Jack London and Hare to cover the activity in Veracruz).[16].

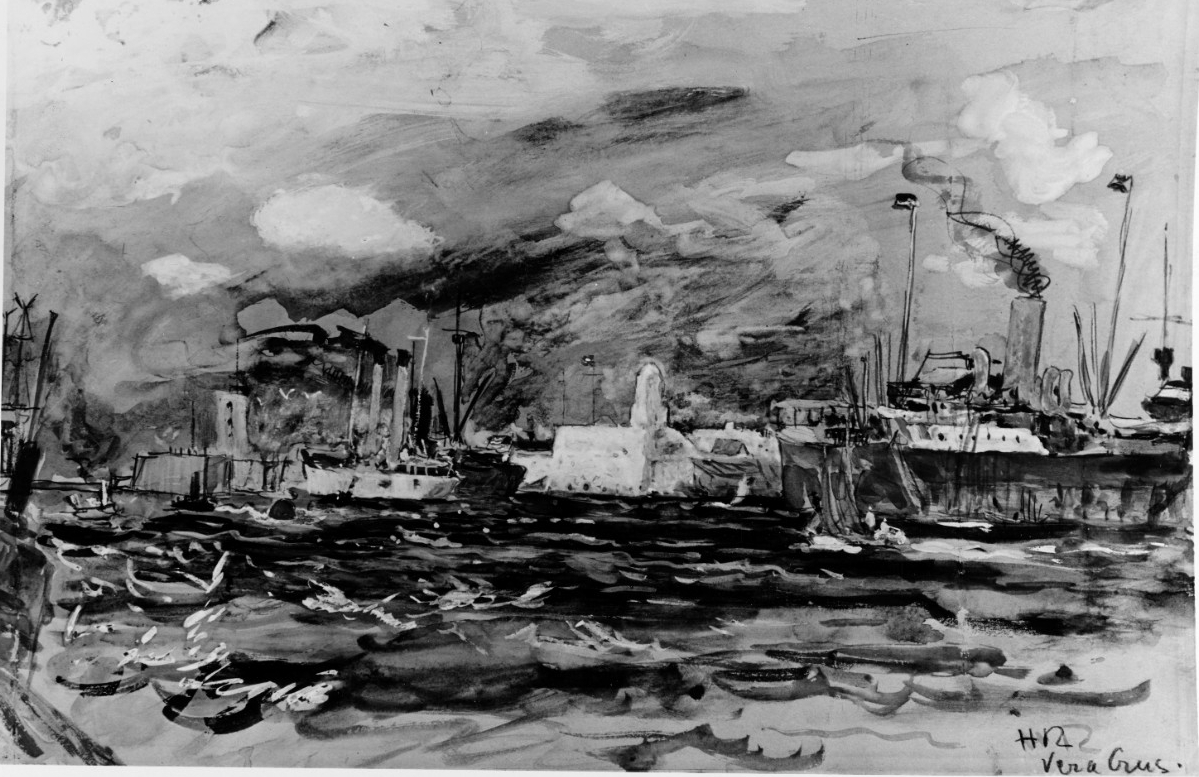

Henry Reuterdahl, a well-known nautical artist, was among his passengers. He sketched while Bellinger flew the plane over the city and its harbor. The image of the painting Reuterdahl created from his aerial sketches was featured in Collier’s Weekly in June 1914. He presented the painting itself to Mustin, who later gifted it to Bellinger.[17] This painting was not the only one that Reuterdahl gifted to a Navy officer. Vice Admiral Paul F. Foster also received a painting, but it was not an aerial view, but a view of the harbor from a ship.[18]

In addition to the coverage by war correspondents, the Curtiss Aeroplane Company used the activity in Veracruz to push their own business. They claimed their hydro-aeroplanes were “The Eyes of the Navy.”[19] Curtiss knew the value of aviators as scouts and used the events at Veracruz to ensure that Navy leaders knew it too.

The detachment flew over 250 flights in 43 days in service, often more than once a day.[20] Mustin reported that:

“‘This expedition has been very valuable in supplying information as to future requirements of Naval aeroplanes and their accessories required for maintenance on board ship and in the field with advance base outfits. . . . [O]ne or more flights have been made every day since the arrival of the Mississippi at Vera Cruz, regardless of weather conditions.’”[21]

Although they flew regardless of the weather, Mustin was aware of meteorological dangers. He admitted to Bristol that the high temperatures and the rain often made conditions more difficult for the pilots.[22]

On 11 June, Captain Mark L. Bristol, director of Naval Aeronautics, finally orchestrated the recall of the aviators to Pensacola.[23] The next day, they left Veracruz. Mustin felt vindicated by the mission to Veracruz. He wrote that “‘[t]he trip has been a very valuable one in the line of future development of Naval Aviation.’”[24] With the lessons learned at Veracruz, Mustin was finally able to convince Bristol of the immediate need for further development of a catapult that would allow aircraft to launch from a ship’s deck. Mustin also realized that flying boats were not as well suited for open seas as he had believed before his experience in Mexico. Hydro-aeroplanes and flying boats, which worked well on inland waters and calm seas, did not prevail in rough waters of the open sea.

Having recently purchased more aircraft for the Navy, Bristol was not happy that “the flying boat type which was considered so excellent a few month ago is now relegated to the scrape heap.” [25] Bristol attributed this shift in Mustin’s opinion of the seaplanes to the rapid development of aircraft rather than a result of operational experience that Mustin gained at Veracruz.

Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels was impressed by the Navy’s aeronautical mobilization at Veracruz. He wrote to Henry Woodhouse that “[a]eroplanes are now considered one of the arms of the Fleet same as battleships, destroyers, submarines, and cruisers.”[26]

The American forces remained at Veracruz even after Huerta went into exile in July. The U.S. Army was the last to depart in November 1914. This mission was practice for the war looming on the horizon in Europe. It was the beginning of naval aerial reconnaissance.

A U.S. Navy aircraft flying over Vera Cruz, Mexico, c. April-May 1914. Photograph taken by J.H. Hare, Collier’s Weekly. (NARA, 19VC-Y-9.)

***

NHHC Resources

Naval Aviation 1911–1986: A Pictorial Study

Papers of Patrick N. L. Bellinger

United States Naval Aviation 1910-2010 .

Other Resources

From Woodrow Wilson’s Inauguration to the Invasion of Veracruz - The Mexican Revolution and the United States (Library of Congress)

Further Reading

Burke, Laurence M. At the Dawn of Airpower: The U.S. Army Navy and Marine Corps' Approach to the Airplane, 1907–1917. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2022.

Campbell, Douglas E. Flight, Camera, Action!—The History of U.S. Naval Aviation Photography and Photo-reconnaissance. Washington, DC: Syneca Research Group, Inc., 2014.

Johnson, Wray R. Biplanes at War: U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in the Small Wars Era, 1915–1934. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2019.

***

Notes

[1] Douglas E. Campbell, Flight, Camera, Action!—The History of U.S. Naval Aviation Photography and Photo-reconnaissance (Washington, DC: Syneca Research Group, Inc., 2014), 24.

[2] P.N.L. Bellinger, “Sailors in the Sky,” VI-1, box 2, folder 1, Papers of Vice Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, Archives Branch (AR), Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), Washington, DC.

[3] Patrick Nieson Lynch Bellinger: 8 October 1885–29 May 1962, Modern Biographical Files, Navy Department Library (NDL), NHHC, Washington, DC.

[4] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 87-88, box 2, folder 2, Bellinger Papers, AR, NHHC. Note the OWL (Over Water and Land) amphibian aircraft being developed by Curtiss in late 1913 were not yet part of the Navy’s airborne inventory, but Bellinger was familiar with the concept and the difficulties that had plagued the development of this type of aircraft.

[5] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 89.

[6] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 89; Bellinger, “Sailors in the Sky,” VI-4, box 2, folder 1, Bellinger Papers, AR, NHHC; New York American, 30 April 1914.

[7] Gerald T. DeForge, Navy Photographer's Mate Training Series, Module 1: Naval Photography (Pensacola, FL: Naval Education and Training Program Development Center, 1981), 1–2.

[8] Bellinger, “Sailors in the Sky,” VI-5; see Thomas, Alfred Barnaby, Militarists, Merchants, and Missionaries: United States Expansion in Middle America (University of Alabama Press, 1970), 111.

[9] Belvidere Daily Republican (IL), 23 May 1914.

[10] Department of the Navy, United State Naval Aviation, 1910–60 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (GPO), 1961), 9.

[11] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 93–94.

[12] E. Percy Noel, ed., “Navy Pilots Seeing Active Service, Aero and Hydro 8, no. 7 (16 May 1914): 1.

[13] Captain Mark L. Bristol to Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin, 2 June 1914, Henry C. Mustin Collection, Navy Department Library (NDL), NHHC.

[14] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 96c.

[15] Bellinger, “Gooney Birds,” 96.

[16] Jack London, “The Red Game of War,” Collier’s Weekly 53, no. 9 (16 May 1914): 5–10.

[17] Bellinger, “Sailors in the Sky,” VI-9.

[18] “Vera Cruz, 1914,” NH-85228, NHHC.

[19]Army and Navy Register and Defense Times 55, no. 1.64 (9 May 1914), 591.

[20]“More Hydroplanes for Navy: Two of Them Will Be of Curtis Type One A Wright and Fourth a Burgess-Dunn,” Tampa Morning Tribune, 5 July 1914, Henry C. Mustin Collection, NDL, NHHC.

[21] Robert J. Cressman, Mississippi II (Battleship No. 23), Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS), NHHC, 22 August 2007.

[22] Mustin to Bristol, 17 June 1914, box 29, folder: Jan–Jun 1914, Mark L. Bristol papers, Library of Congress (LOC), Washington, DC.

[23] Bristol to Lieutenant Mustin, 11 June 1914, Mustin Collection, NDL, NHHC.

[24] Clarke Van Vleet, “Action at Veracruz,” Naval Aviation News 58 (April 1976): 39.

[25] Mary Bristol to Lt. Cmdr. H. C. Mustin, 23 May 1914, Mustin Papers, NDL, NHHC.

[26] Secretary of Navy Josephus Daniels to Mr. Henry Woodhouse, 19 May 1914, in Henry Woodhouse, “Textbook of Naval Aeronautics” (New York: The Century Co., 1917), 137.

***

Bibliography

Articles

Armstrong, William J. “Aircraft Go to Sea: A Brief History of Aviation in the U.S. Navy.” Aerospace Historian 25, no. 2 (1978): 79–91.

Evans, Mark L. “‘Performed All Their Duties Well.’” Naval History 23, no. 5 (October 2009).

Goodspeed, Hill. “Flight Line.” Naval History 25, no. 1 (January 2011).

Owsley, Frank L., Jr., and Wesley Phillip Newton. “Eyes in the Skies.” Proceedings of the United States Institute 112, no. 4, supplement (April 1986): 17–25.

Van Vleet, Clarke. “Action at Veracruz.” Naval Aviation News 58 (April 1976): 36–39.

Books

Burke, Laurence M. At the Dawn of Airpower: The U.S. Army Navy and Marine Corps' Approach to the Airplane, 1907–1917. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2022.

Campbell, Douglas E. Flight, Camera, Action!—The History of U.S. Naval Aviation Photography and Photo-reconnaissance. Washington, DC: Syneca Research Group, Inc., 2014.

Johnson, Wray R. Biplanes at War: U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in the Small Wars Era, 1915–1934. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2019.

Packard, Wyman H. A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence. Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1994.

Russell, Sandy. Naval Aviation, 1911–1986: A Pictorial Study. Washington, DC: Naval Air Systems Command, 1986.

Swanborough, Gordon, and Peter M. Bowers. United States Navy Aircraft Since 1911. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990.