Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Pearl Harbor Attack

On a quiet Sunday morning on Dec. 7, 1941, in one of the most defining moments in U.S. history, two waves of Japanese Imperial Navy aircraft attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet and nearby military airfields and installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The first wave—more than 170 dive-bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters—appeared over Pearl Harbor at 7:55 a.m. Within the first 30 minutes, most of the damage had been done. At the airfields on Ford Island and adjoining Wheeler and Hickam Fields, American aircraft were parked closely together, which made them easy targets for Japanese strafing. At Wheeler Field, in particular, of the 126 planes on the ground, 42 were destroyed and 41 were damaged, leaving only 43 fit for service. Only a handful of U.S. aircraft were able to get in the air to repel the first wave of attacks. In all, more than 180 U.S. aircraft were destroyed. As for the ships anchored at Pearl Harbor, Battleship Row was in complete shambles. USS Arizona (BB-39) took two bomb hits, triggering a catastrophic explosion that ripped through the forward part of ship. USS West Virginia (BB-48) was riddled with bombs and torpedoes, but was not sunk due to extraordinary damage control measures. USS Oklahoma (BB-37) sustained three torpedo hits almost immediately. As it capsized, six more torpedoes struck home. USS California (BB-44) was torpedoed and ordered abandoned as it slowly sank in shallow water. USS Utah (AG-16), which was converted from a battleship to a radio-controlled target ship in 1931, took a torpedo hit and rolled over.

At 8:50 a.m., the second wave—more than 160 aircraft—of the attack began. Although less successful than the first, it nonetheless inflicted heavy damage. USS Nevada (BB-36), which had taken a torpedo hit during the first wave of the attack, was struck by seven or eight bombs and was grounded at the head of the Pearl Harbor channel. Dry-docked USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) was set ablaze by bombs, and the two destroyers in dry dock with it were reduced to wrecks. Destroyer USS Shaw (DD-373) took three bomb hits that sparked widespread fires, causing its forward magazine to blow up. Shortly afterward, the Japanese withdrew.

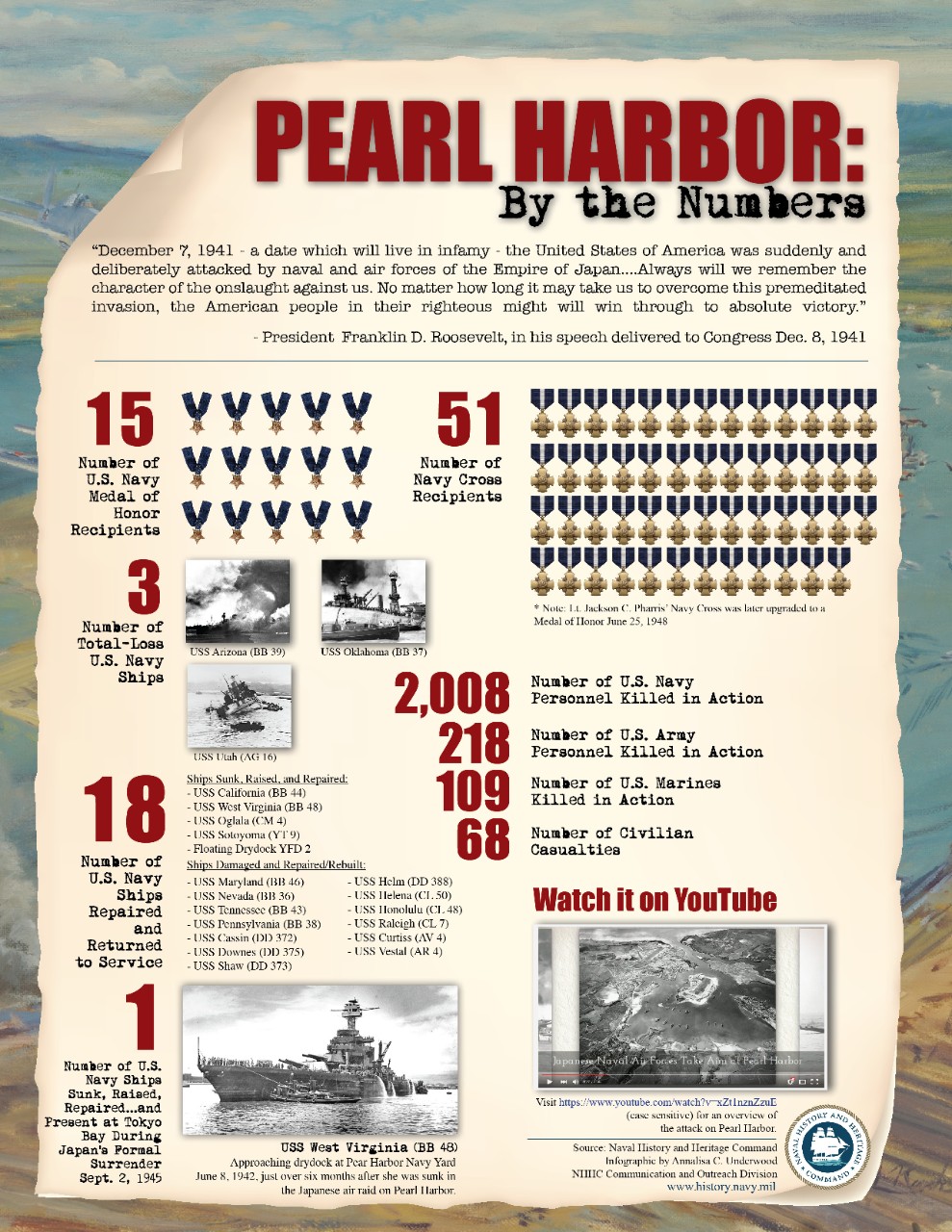

Casualties were staggering—2,008 Navy, 109 Marine Corps, 218 Army, and 68 civilian personnel were killed or missing. More than 1,100 were wounded. Arizona suffered the most casualties, with 1,177 of the 1,512 on board the ship losing their lives. More than 400 were lost on board Oklahoma. Japanese losses amounted to fewer than 100 men, 29 planes, and five mini-submarines.

Although the attacks were devastating to the Pacific Fleet, none of the American aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor at the time of the attacks. USS Enterprise (CV-6) was on a mission to reinforce the Wake Island garrison, USS Lexington (CV-2) was undertaking a similar mission to ferry dive-bombers to Midway, and USS Saratoga (CV-3) was embarking aircraft in San Diego. These operations also meant that seven heavy cruisers and a division of destroyers were at sea. In addition, the Japanese focus on ships and planes spared fuel tank farms, naval yard repair facilities, and the submarine base, which would be crucial in the upcoming months. Moreover, only three ships, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Utah, were ultimately lost. The rest of the ships damaged during the Pearl Harbor attacks were repaired or rebuilt and returned to the fleet. In the aftermath, President Franklin D. Roosevelt unified public support and dispelled any earlier support for neutrality. On Dec. 8, Congress declared war on Japan. On Dec. 11, both Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

Acts of extraordinary bravery were in abundance on the “date that will live in infamy.” Often at the sacrifice of their own lives, Sailors, Marines, and Soldiers fought back. Those without weapons helped in any way they could. Nurses, doctors, and corpsmen spent countless hours evacuating and tending to the wounded. Pilots took off in their aircraft to fight the Japanese despite overwhelming odds. Fifteen Navy personnel would later receive the Medal of Honor (10 posthumously) for acts of courage above and beyond the call of duty. Among the Sailors recognized with the nation’s highest honor were Chief Water Tender Peter Tomich onboard Utah, who sacrificed his life to prevent the boilers from exploding, enabling boiler room crews to escape before the ship capsized. Another was Chief Boatswain Edwin J. Hill, who cast off the lines as Nevada got underway and swam through burning oil to get back on board his ship, where he was killed by Japanese strafing. He was credited with saving the lives of many junior Sailors. Ensign Francis Flaherty and Seaman First Class James Richard Ward, on board Oklahoma, sacrificed their lives to enable turret crews to escape before the ship capsized. On board California, Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves, Machinist's Mate First Class Robert R. Scott, and Ensign Herbert C. Jones stayed at their posts at the cost of their lives to keep power and ammunition flowing to the antiaircraft guns as long as possible. Rear Adm. Isaac C. Kidd and Capt. Franklin Van Valkenburgh on board Arizona and Capt. Mervyn S. Bennion on board West Virginia directed the defense of their ships under heavy fire, until the ships were sunk and they were killed. Fifty-one Navy personnel were also awarded the Navy Cross.

Hudner’s Heroic Attempt to Save His Wingman

On Dec. 4, 1950, while en route to provide air support for American ground forces battling thousands of Chinese soldiers during the pivotal Battle of Chosin Reservoir, Ensign Jesse L. Brown’s Vought F4U-4 Corsair was hit by antiaircraft fire behind enemy lines. After losing oil pressure and control of the aircraft, Brown was forced to make an emergency landing on the side of a North Korean mountain that was covered in heavy snow. After he crashed, Lt. (j.g.) Thomas J. Hudner, Jr., who was circling overhead, realized something was wrong when Brown did not emerge from the cockpit of his wrecked aircraft. Risking a potential court-martial, capture by the Chinese, and his own life, Hudner made the decision to crash-land his own aircraft in the vicinity of Brown in an attempt to save his wingman’s life.

After wading through 50 yards of waist-deep snow, Hudner found Brown with a crushed leg, bleeding, trapped by a damaged instrument panel, and already suffering from the sub-zero temperatures. Hudner tried multiple times, without success, to pull Brown from the cockpit. He packed snow into the burning engine with his bare hands and around Brown in an attempt to smother the flames and protect his fellow naval aviator. Hudner then waded back to his aircraft to radio that he needed an ax and a fire extinguisher. A Marine Sikorsky rescue helicopter, piloted by Marine 1st Lt. Charlie Ward, was already on the way, but had to turn back to get the requested items. As daylight quickly disappeared, the helicopter arrived at the crash site. Ward tried to put out the fire with the extinguisher, but the engine continued to burn relentlessly. Hudner took the ax to the downed aircraft, but it just bounced off it. At that point, Brown began to succumb to his injuries. His final words were, “Tell Daisy [his wife] how much I love her.” Both men continued to take turns trying to break through the aircraft’s exterior with the ax, but it did nothing except make dents. Eventually, Ward gave Hudner an ultimatum—stay or go. If he stayed, he would surely freeze to death and there wouldn’t be another rescue mission overnight. Reluctantly, Hudner chose to leave with the rescue helicopter, going first to a temporary Marine base at Haguru-ri, and eventually back to his ship, USS Leyte (CV-32), where he begged the command to return to the crash site to retrieve Brown’s body. His request was ultimately denied due to the extreme enemy threat in the vicinity of the site.

Brown was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Purple Heart. Ward received the Silver Star for volunteering for the dangerous rescue mission. On April 13, 1951, Hudner received the Medal of Honor during a ceremony hosted by President Harry S. Truman.

While at the White House, Hudner met Brown’s widow, Daisy, and the two remained in contact throughout their lives until she died in 2014. Hudner would serve 27 years in the Navy before he retired from the service. In retirement, Hudner found a new passion and was extremely active in the Massachusetts veterans’ community, even going so far as to serve as the commissioner of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Veterans’ Services from 1991 to 1999. Hudner passed away on Nov. 13, 2017, at his home in Concord, Massachusetts. He was 93 years old. He was the last living Navy recipient of the Medal of Honor from the Korean War. Arleigh Burke–class destroyer USS Thomas Hudner (DDG-116) proudly bears his name. The film Devotion recently hit the theaters, which documents Hudner’s heroic attempt to save Brown. NHHC has a toolkit on its website that includes promotional clips of the film.

Today in Naval History

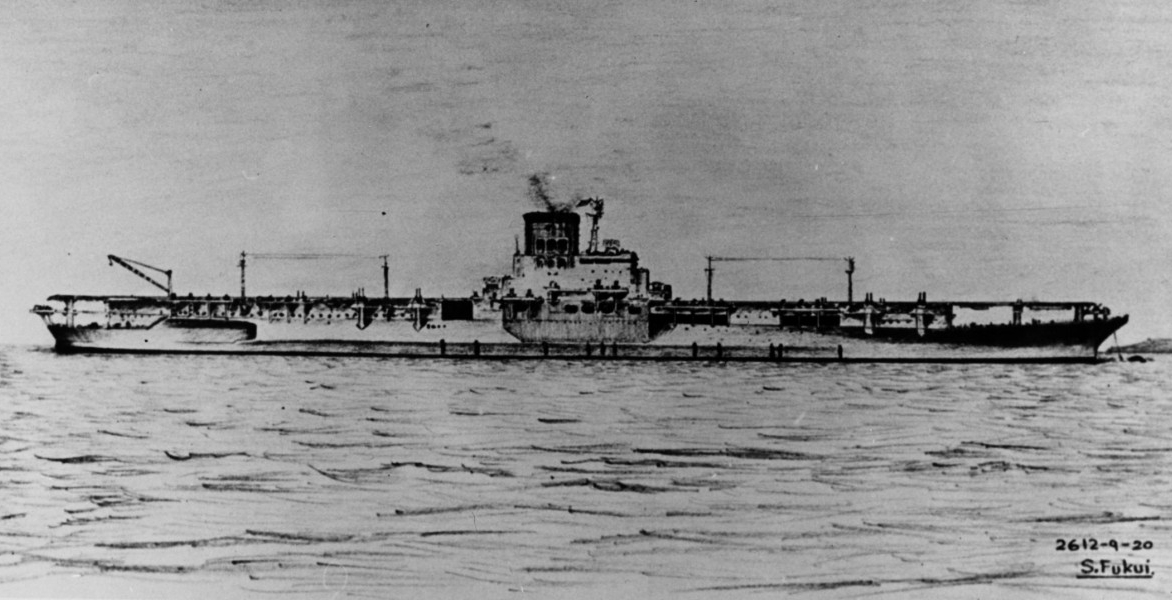

In the early morning of Nov. 29, 1944, USS Archerfish (SS-311) sank Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano about 180 miles southwest of Tokyo Bay. At the time, Shinano was the largest warship ever built, with 72,000-ton displacement. Archerfish was on its maiden voyage when it sent the massive carrier beneath the waves.

Laid down at Yokosuka before the United States entered World War II, Shinano was originally built to be one of the Japanese Yamato-class super-battleships. However, after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, construction was temporarily halted. After the loss of four Japanese carriers at the Battle of Midway, Shinano was redesigned and constructed as an aircraft carrier. Shinano had an armored flight deck and was designed to host a variety of advanced aircraft that included Mitsubishi A7M Reppu “Sam” fighters, Aichi B7A Ryusei “Grace” torpedo bombers, and Nakajima C6N Saiun “Myrt” reconnaissance planes. U.S. intelligence had no idea the ship was being constructed. The first time that the Allies became aware of Shinano’s existence was when a B-29 bomber flying a reconnaissance mission spotted the ship during its initial sea trials on Nov. 1, 1944. Concerned the carrier would be an easy bomber target, the Japanese rushed construction of the ship and commissioned it on Nov. 19.

On Nov. 28, Shinano was underway from Yokosuka bound for Kure under the command of Capt. Toshio Abe. The ship, still under construction, was escorted by three destroyers and was carrying 50 Okha rocket-propelled suicide aircraft and six Shinyo suicide boats. Meanwhile, Archerfish, commanded by Cmdr. Joseph Enright, was off the coast of Japan to provide lifeguard services for downed B-29 bomber crews. As there were no bombing missions scheduled for Nov. 28, Archerfish was free to come off station and hunt for enemy vessels.

At dusk, lookouts on Archerfish spotted what was initially thought to be a large tanker with escorts departing Yokosuka. For more than six hours, Archerfish tracked the enemy movement and continually maneuvered to get into position for a submerged attack. Enright ruled out a surface attack due to the presence of the destroyers. In a stroke of luck, Shinano turned, giving Archerfish an almost ideal shot. At a range of 1,400 yards, the crew of Archerfish fired all six bow tubes, with the torpedoes set to run shallow in order to hit the ship just below the waterline. After remaining at periscope depth long enough to see the first two torpedoes explode against Shinano’s starboard side, Enright ordered Archerfish to 400 feet to avoid a depth-charge counterattack. Four torpedoes ultimately hit the enemy aircraft carrier.

After the severe damage Shinano had endured from the strikes, Abe ordered the port trimming tanks and three outboard port boiler rooms flooded to counter the continued list. Initially, the ship maintained course and speed. However, since incomplete construction impacted watertight integrity, flooding continued through numerous parts of the ship. Shinano had steamed about 36 miles from the torpedo strike when the ship’s boiler feed failed and it went dead in the water. Two of the escort destroyers attempted to tow Shinano, but were unsuccessful due to the carrier’s size and its continued list. At 10:18 a.m., Abe ordered abandon ship. About 45 minutes later, Shinano rolled completely over and sank by the stern. Abe chose to go down with his ship. Another 1,435 of the crew were also lost. More than 1,000 crew and civilian workers were rescued.

Initially, Archerfish was given credit for sinking a cruiser, as U.S. intelligence was not aware of any carriers in that area. However, Enright produced a detailed sketch and was given credit for sinking an enemy carrier. Only after the war were the true details and the immense size of Shinano known. Enright would ultimately receive the Navy Cross and Archerfish a Presidential Unit Citation for sinking Shinano, the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

Army-Navy Football Game

Go Navy! Beat Army! It is one of the most traditional and enduring rivalries in college football. Dubbed “America’s Game,” the 123rd Army-Navy football game is scheduled to take place this year on Dec. 10 at 3 p.m. at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia. The Navy Midshipmen currently lead the overall series 62–53–7. In what has become a tradition, both teams will wear alternate uniforms for the big game. This year, Navy will wear uniforms that are dedicated to U.S. Naval Academy graduates who have gone on to be astronauts. Alan Shepard, a 1944 graduate of the academy, was the first American in space in 1961 and served as one of NASA's first seven astronauts. He also landed on the moon as part of the Apollo 14 crew in 1971. Fellow graduate Bruce McCandless was the first astronaut to go on an untethered spacewalk in 1985. Navy's helmet will feature handcrafted paintings of the McCandless’ spacewalk with Earth in the background. The other side of the helmet will feature the NASA logo. The uniforms will be white with red stripes and blue American flag markings. Army’s uniforms are dedicated to the Soldiers of the 1st Armored Division during World War II. This year is the 80th anniversary of Operation Torch, which was the beginning of the United States’ ground offensive in North Africa and Europe.

The rivalry game between Army and Navy was first played at West Point, New York, on Nov. 29, 1890. Navy won the contest 24–0. The midshipmen had an advantage for their first game against the cadets because they had been playing football since 1879. Army had just started playing in 1890. In the early years, the game was cancelled a number of times. From 1894 to 1898, it was mandated that the service schools could only play home games, and due to World War I, the game was cancelled in 1917 and 1918. Disagreement about the rules also cancelled the game in 1928 and 1929. The game became an annual event in 1930 and was even played throughout World War II. Recently, victories have been back and forth. Last year, Navy won 17–13. From 2002 to 2015, Navy dominated Army with 14 straight wins.

Traditions have also become an integral part of the game. “March On” opens the game, when both the midshipmen and cadets assemble on the field in formation. Another tradition before the game is the “prisoner exchange.” As part of the Service Academy Exchange Program, some students spend the fall semester at another academy. Midshipmen and cadets who participate are sent back to their home team to root for their school. If the president is in attendance, he changes sides during halftime to show support for both Army and Navy. Once the game is complete, the singing of the alma maters takes place. The team that lost sings first followed by the players and alumni of the winning team. For more on Navy athletics and scores from all the Army-Navy football games, visit NHHC’s website.