Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On May 31, 1919, Curtiss flying boat NC-4 landed at Plymouth, England, concluding the first transatlantic flight by a U.S. Navy aircraft. The record-setting flight was a few years in the making with the development of larger and faster flying boats accelerating dramatically during World War I. Flying boats were found to be particularly useful at preventing German U-boats from attacking convoys, because they forced them to dive. In May 1919, the Navy only had three operational flying boats, with NC-4 making its first test flight on April 30, 1919, which was the aircraft’s first and only flight before the transatlantic attempt. The transatlantic mission was a major affair, with more than 50 U.S. Navy ships, mostly destroyers, assigned to take station along the intended flight route to provide beacon and rescue services if necessary.

On May 8, 1919, three flying boats (NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4) launched from Naval Air Station Rockaway, New York, under the overall command of Commander John H. Towers. The three aircraft first flew to Chatham Naval Air Station, Massachusetts. However, NC-4 suffered an oil leak in the pusher engine and a thrown rod in the center tractor engine, and was forced to land in the ocean. It was subsequently located and towed in—fortunately, the aircraft remained airworthy. The three flying boats then launched for Trepassy, Newfoundland, but NC-4 again encountered mechanical problems and had to make an intermediate stop at Halifax, Nova Scotia, for repair, before continuing on to Trepassy. In the meantime, NC-1 and NC-3 attempted to take off from Trepassy to continue the next leg of the journey to the Azores, but were unable to get airborne because they were too heavy with fuel. On May 16, the three aircraft attempted to take off from Newfoundland to the Azores, the longest leg of the journey, but once again, NC-1 and NC-3 were unable to launch and NC-4 had to return to Newfoundland. After more weight and balance shifting, all three aircraft finally launched. Twenty-two Navy ships were stationed along the next leg of the journey at about 50-nautical-mile intervals and were illuminated at night. The following day, a fog bank further hampered the flight. NC-1 and NC-3 were both forced to land in the ocean, each incurring damage that made further flight impossible. The crew of NC-1 was picked up by Greek freighter Ionia, which tried to take NC-1 under tow, but the lines parted. Gridley (Destroyer No. 92) arrived and took NC-1 under tow. After three days, NC-1 broke apart and sank. NC-3 drifted about 200 miles and came into sight of the Azores, however, she was no longer airworthy. Ultimately, NC-4 made it to the Azores on the afternoon of May 17.

On May 20, NC-4 launched, but had to turn back about 150 nautical miles out due to mechanical problems. After receiving repairs and spare parts, NC-4 took off again on May 27, and after a flight of 9 hours and 43 minutes, landed on the Tagus River at Lisbon—becoming the first American aircraft to fly across the Atlantic. On May 31, NC-4 flew from Lisbon to Plymouth, becoming the first U.S. aircraft to fly from the United States to England. NC-4 was met by a large escort of Royal Air Force aircraft, a 21-gun salute from a British warship, and huge crowds. Lt. Cmdr. Albert Cushing Read, commander of NC-4, was awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal (at that time, the second-highest award, ahead of the Navy Cross). The other five members of the NC-4 crew received the Navy Cross. Towers also received the Navy Cross for his leadership of the three flying boats.

NC-4 was, for a time, on display at New York’s Central Park before it was donated by the Navy to the Smithsonian in 1920. Only the hull was displayed at the Smithsonian, as the museum had no place big enough to fit the aircraft. In 1974, the Smithsonian loaned NC-4 back to the Navy. It is currently on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. For more naval aviation firsts, visit NHHC’s website.

WWII@80: Battle of Midway

Following the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific in wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese conducted military operations against U.S., British Commonwealth, and Dutch possessions in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. The first phase of their operations were the seizure of Malaysia, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, and various island groups in the central and western Pacific. The second phase was to isolate and neutralize Australia and India. The plan envisioned the seizure of bases in Papua/New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, which in turn would be used to support future operations against New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. By early March 1942, with the seizure of Lae and Salamaua, the entire north coast of Papua-New Guinea had fallen to the Japanese.

At the time, U.S. Navy cryptanalysts in Melbourne, Australia, and Pearl Harbor intercepted Japanese radio communications and, through traffic analysis and codebreaking, uncovered the location of major fleet units and shore-based air forces. There was a third radio intercept unit, but it was lost when U.S. forces surrendered to the Japanese at Corregidor in the Philippines. The units at Melbourne and Pearl Harbor, by translating messages and studying operational patterns, were able to predict Japanese operations with some degree of certainty. The analysts daily briefed senior American commanders, including Adm. Earnest J. King, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet, and Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. Following early American carrier raids on Japanese shipping at Lae and Salamaua, in March, Adm. Shigeyoshi Inouye, commander in chief of the Japanese Fourth Fleet, concluded the Japanese were not assured of air superiority in the region. However, it was not until early May that Inouye had three carriers available for the planned seizure of Port Moresby. From May 7–8, the first carrier battle of the war, Battle of the Coral Sea, took place. Each side suffered the loss of a carrier—USS Lexington (CV-2) and Japanese light carrier Shoho. USS Yorktown (CV-5) was also heavily damaged.

In early 1942, evidence began to appear that the Japanese intent was to expand east of the Marshall Islands. Indications of land-based air units and equipment began appearing in message traffic to and from the Marshall Islands and other Japanese-occupied Pacific territories. In March, the designator “AF” began appearing in partially decoded messages. On March 13, American cryptanalysts both broke the Japanese navy's general-purpose code and tentatively identified “AF” as Midway. In April, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, convinced the Imperial General Staff to agree to his risky Midway and Aleutian strategy, which included a diversionary maneuver toward Alaska followed by the invasion of Midway. The Japanese knew the U.S. Pacific Fleet would respond to the landings on Midway. The plan was for Japanese carrier and battleship task forces—waiting unseen to the west of the island—to fall upon and destroy the unsuspecting Americans. If successful, the plan would eliminate the U.S. Pacific Fleet for a least a year and would provide a forward outpost that would provide ample warning of any future threats from the United States. The April 1942 Doolittle Raid reinforced the need for an extended Japanese first line of defense and for an advanced timeline for the Midway operation. On May 5, Imperial General Headquarters issued “Navy Order No. 18,” which directed Yamamoto to carry out the Midway and Aleutian operations. At the same time, Japanese navy communication dramatically increased, reflecting preparation for the operations. On May 7, Pearl Harbor cryptanalysts provided to senior Navy leadership a translation of Japanese ambitions to obtain air superiority over a target, assist in amphibious landings, and bombing and strafing attacks to wipe out local resistance. Two days later, Melbourne intercepted and translated “1st Air Fleet Striking Force Order No. 6,” which confirmed the creation of a new carrier strike force and a major fleet movement planned to begin on May 21. Cryptanalysts from Pearl Harbor predicted that an attack on Midway would happen on June 4. Nimitz used the intelligence to prepare American countermeasures, which included reinforcement of the forces already on Midway.

On May 26, the Japanese Northern Force steamed from Japan toward the Aleutians. The next day, Japanese forces were underway for Midway. Among them was the First Mobile Force/Carrier Strike Force, which was comprised of the four large carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, with a total of 229 embarked aircraft. Two days later, the Japanese First Fleet/Main Body (Yamamoto in battleship Yamato) was underway. The Second Fleet/Escort Force, which included 15 transports, sailed from Saipan and Second Fleet/Occupation Support Force sortied from Guam. These forces were supported by 17 patrol seaplanes. Meanwhile, Rear Adm. Raymond A. Spruance’s Task Force 16 (TF 16), formed around USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Hornet (CV-8), departed Pearl Harbor on May 28. Two days later, Task Force 17 (TF 17), formed around Yorktown steamed toward the area northeast of Midway. The task forces meet on June 2 about 350 miles northeast of Midway. The three U.S. carriers, augmented by cruiser-launched floatplanes, provided 234 aircraft afloat. These were supported by 110 fighters, bombers, and patrol planes based on Midway. As part of the pre-battle disposition, 25 U.S. submarines were deployed around Midway.

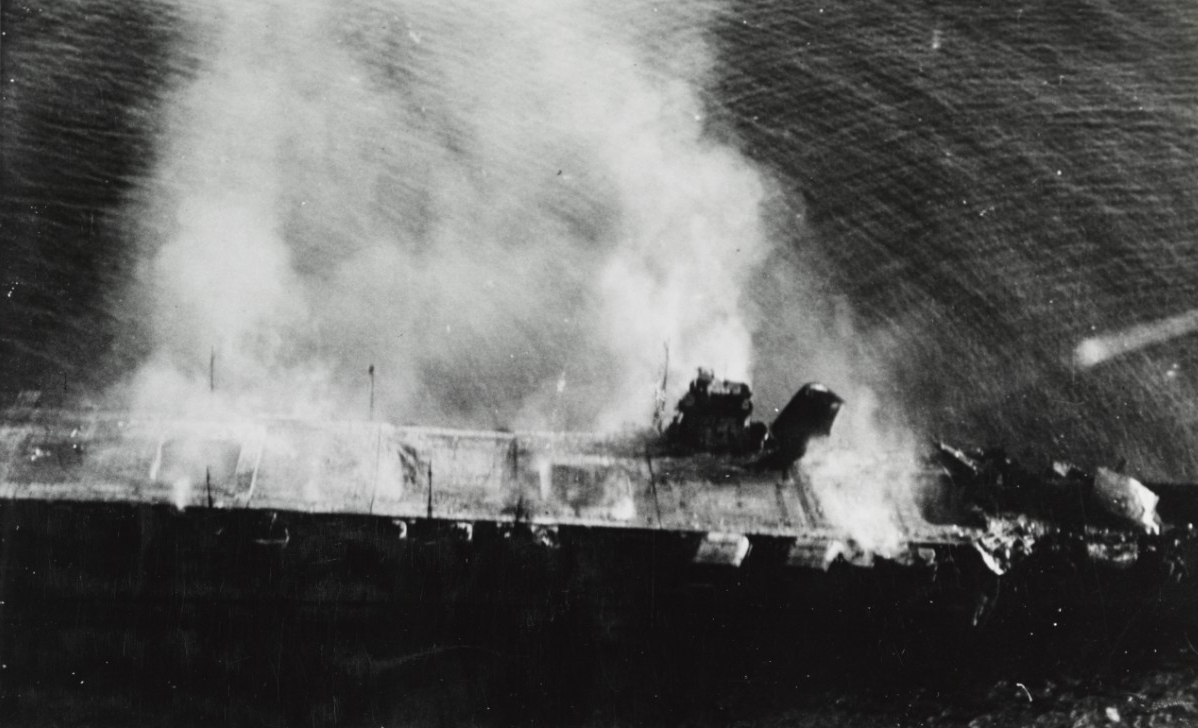

On June 4, shortly after midnight, patrol planes reported on the course and speed of the Japanese “main body,” also noting their distance of 574 miles away from Midway. Shortly after dawn, a patrol plane spotted two Japanese carriers and their escorts, reporting “Many planes heading Midway from 320 degrees distant 150 miles!” Between 9:30 and 10 a.m., Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers from the three American carriers began to attack the Japanese carriers. Although completely wiped out by the defending Japanese fighters and antiaircraft fire, they drew off enemy aircraft, leaving the skies wide open for dive-bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown. Douglas SBD Dauntlesses from Enterprise bombed and fatally damaged carriers Kaga and Akagi, while SBDs from Yorktown bombed and wrecked carrier Soryu. At 11 a.m., Hiryu, the one Japanese carrier that escaped destruction, launched dive-bombers that temporarily disabled Yorktown. Three and a half hours later, Hiryu's torpedo planes struck a second blow, forcing Yorktown's abandonment. In return, Dauntlesses from Enterprise mortally damaged Hiryu in a strike around 5 p.m. The destruction of the Carrier Strike Force compelled Yamamoto to abandon his Midway invasion plans, and the Japanese fleet began to retreat westward.

The following day, TF 16 pursued the remaining Japanese fleet, while work continued to salvage Yorktown. Both Akagi and Hiryu, damaged the previous day, were scuttled by Japanese destroyers. The last air attacks of the battle took place on June 6, when dive bombers from Enterprise and Hornet bombed and sank heavy cruiser Mikuma, and damaged destroyers Asashio and Arashio, as well as the cruiser Mogami. After recovering its aircraft, TF 16 turned eastward and broke off contact with the enemy. Also on June 6, Japanese submarine I-168 interrupted U.S. salvage operations on Yorktown, torpedoing the carrier and sinking destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412). Screening destroyers in the area depth-charged I-168, but the Japanese submarine escaped. Yorktown finally rolled over and sank at dawn on June 7.

Due to U.S. intelligence efforts, judicious aircraft carrier tactics, and a little luck, the U.S. Navy inflicted a resounding defeat on the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Battle of Midway. Although Yorktown was lost, the Japanese lost four carriers—all of which had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Importantly, the Japanese lost more than 100 trained pilots. The balance of sea power in the Pacific had begun to shift in the Allies favor, as did the tide of the war.

Invasion of Normandy

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, nearly 7,000 U.S. and British ships and craft with nearly 160,000 troops began the largest amphibious landing in history off Normandy, France. Operation Overlord (D-Day) was the beginning of the Allies’ march eastward to end Nazi Germany’s occupation of Europe and Adolf Hitler’s tyrannical rule. The landings surprised German commanders, who had overestimated the adverse weather’s impact and were expecting the massive assault to take place farther northeast, in the Pas-de-Calais area. The first wave of troops to land at Omaha Beach were killed by the hundreds by the enemy, who was well dug in. Some landing craft never even made it to shore, and on others that did, no one survived. Navy coxswains from disabled craft fought as infantrymen using weapons taken from the dead. Navy combat demolition teams were in the second wave of the attack to destroy beach obstacles; however, most didn’t make it ashore. The same fate struck many personnel of the Navy beach battalions, beachmasters, and naval shore fire-control teams. Navy physicians and corpsmen, who went ashore in the first wave, suffered extremely high casualties. Only a couple of hours into the landings, Omaha Beach was so littered with destroyed landing craft, tanks, vehicles, uncleared German obstacles, and hundreds of dead bodies that continuing the assault seemed an impossibility.

Although the Germans also fought ferociously at the other four Normandy beaches, those landings went relatively well. Omaha, on the other hand, was a different story. The Germans were holding the higher ground above the beach, and the Americans had to find a way to break through the enemy defenses. They found ways to innovate on the spot, providing fire support to troops without the benefit of shore spotting due to most of the troops’ radios having been lost. Several U.S. destroyers came within 1,000 yards of shore to provide gunfire support, and one managed to move within 400 yards, close enough to come into range of rifle fire. By 9:50 a.m., all U.S. destroyers and a few British destroyers were ordered to close the beach, risking mines, shore battery fire, and the strong possibility of running aground in the shallows. As the fire from the destroyers began to take their toll on the Germans, Soldiers, with many of their leaders already dead, fought their way up 100-foot bluffs in bloody close combat to eventually take Omaha Beach.

Although the invasion of Normandy was successful and was the beginning of the end for the Nazi regime, the cost was horrendous. Allied casualties on June 6 alone have been estimated at 10,000 killed, wounded, or missing in action. In terms of how many warships the Navy lost on D-Day, destroyer USS Corry (DD-463) was hit by German shore fire and then probably succumbed to a mine in the opening assault on Utah Beach. In addition, minesweeper USS Osprey (AM-56), and numerous amphibious craft, including 9 LCIs and 26 LCTs, were lost. In the days that followed, destroyers Glennon (DD-620) and Meredith (DD-726), destroyer escort Rich (DE-695), minesweeper Tide (AM-125), 5 LSTs, and the troop transport Susan B. Anthony (AP-72) were sunk by the Germans, mostly by mines, as they protected the flow of troops and supplies into the Normandy beachhead. For more on the Navy’s role in the invasion of Normandy, read Operation Neptune: The U.S. Navy on D-Day at NHHC’s website.

First U.S. Navy Vessel to Circumnavigate the Globe

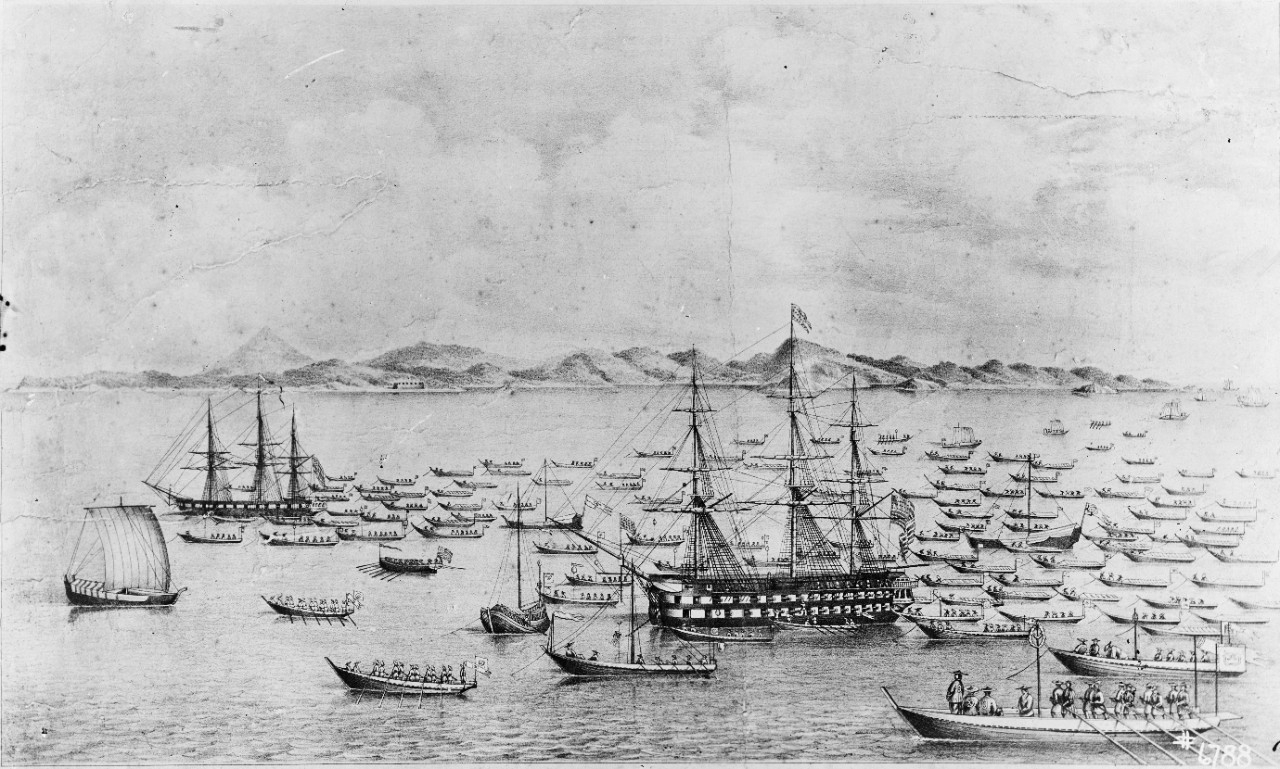

During her 41 years of service in both peace and war, sloop-of-war Vincennes compiled an unprecedented record of achievements in polar exploration, global cartography, and commercial expansion and protection. Her career mirrored that of a young, expanding nation, and began when she set sail from New York on Sept. 3, 1826, with Master Commandant William Bolton Finch in command. Accompanied by frigate Brandywine, Vincennes rounded Cape Horn and then cruised in Pacific waters to protect American merchantmen and whalers until June 1829. After more than two and a half years protecting American interests, Vincennes received orders that sent her to the Society Islands, then to the Sandwich (now Hawaiian) chain, and ultimately to Macao, China, which she reached in early 1830. From Macao, Vincennes hoisted her sails for the Philippines, reaching Manila on Jan. 29. About a week later, she was underway, sailing across the Indian Ocean and arriving at Capetown, South Africa, 56 days later. After a brief stop at St. Helena, Vincennes returned to New York on June 8, 1830, to become the first American vessel to circumnavigate the globe. Later, Finch wrote, in reference to the unprecedented circumnavigation, that “none is more trying to a ship's qualities, hull, rigging and spars, and only such vessel as is most perfect in every respect, ought to undertake it.” During the voyage, Finch also corrected earlier surveys of the Pacific Basin, discovered two islands west of the Society group, and actually sailed over the charted location of a third.

After the voyage, Vincennes was decommissioned and underwent extensive repairs at New York. She was then ordered to take up station in the West Indies to protect American commerce from pirates. She visited Cuba and Jamaica in May 1831, but yellow fever broke out onboard the ship, so she sailed to Pensacola, Florida, where she remained for nearly a year while the disease ran its course. Finally, she sailed for the Portsmouth Navy Yard, where she was decommissioned on Aug. 19, 1832, for an extensive overhaul.

On June 1, 1833, Vincennes was put back in commission with Cmdr. Alexander S. Wadsworth in command, and the ship departed Portsmouth for her second Pacific cruise. She rounded Cape Horn in early 1834 with orders to visit the Fiji and Palau Islands, China, Sumatra, and search for shipwrecked and stranded American seamen. Taking a more southern route westward from South America than taken previously by any American vessel, Vincennes became the first American ship to call at Guam. On Jan. 24, 1836, she arrived at Singapore, passed through the Straits of Malacca, and called at Quallah Battu on the west coast of Sumatra on Feb. 15. Continuing westward, Vincennes provisioned at Capetown and St. Helena, then ported at Hampton Roads, Virginia, completing her second circumnavigation of the globe.

Vincennes rounded out her distinguished career as flagship for Lt. Charles Wilkes’ South Sea Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Antarctic and South Pacific, a trip to Japan to negotiate foreign trade, and participation in the American Civil War. The veteran world traveler was eventually sold at an auction in Boston on Oct. 5, 1867.