Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Happy Birthday U.S. Navy!

On Oct. 13, 1775, a resolution by the Continental Congress established what is now the United States Navy, “…a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportional number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted, with all possible dispatch, for a cruise of three months….” Following the American Revolution and after decades of debate, the U.S. Constitution empowered Congress “to provide and maintain a navy.” Acting on this authority, the Department of the Navy was established on April 30, 1798. In 1972, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., officially authorized Oct. 13 as the Navy’s birthday. This year’s theme is “On Watch — 24/7 for 247 Years,” which highlights the U.S. Navy's enduring ability to remain fully ready to respond to and effectively deter emergent threats.

After the colonies gained their Independence from Great Britain, the Continental Navy was deemed irrelevant and thought to be too expensive to continue and fund. The 13 former colonies had a loose arrangement of sovereignty, and the central government did not have the taxation powers to fund something as expensive as building new ships and training sailors. In addition, peace with England gave no real reason for a new American Navy. Nevertheless, danger continued on the high seas. In 1785, Barbary pirates seized their first American vessel (the first of many) and tried to ransom the passengers and crew. Rapidly, American merchant ships were considered helpless against foreign attacks. In addition, volatile relations between the United States, Great Britain, and France further complicated the issue of security for free trade among sovereign nations. Over the course of the French Revolutionary Wars which quickly spilled out in the Atlantic, American neutrality became somewhat difficult. American merchants pressed Congress for a standing naval force that could defend them against ships of war and pirates. Furthermore, when France and Britain began to wage economic war on each other, the British government blocked American ships from the West Indies—a crucial source for sugar and other commodities. To complicate matters further, British ships harassed and attacked American merchants in an effort to choke the economy of France and diminish French war-making capabilities. President George Washington and Secretary of State Edmund Randolph implored Congress to take action for the sake of America’s neutrality status.

Nonetheless, Congress continued to ignore the requests. As the president, his supporters, and mostly Federalists saw a navy as prosperity at home and protection on the high seas, Anti-Federalists had their reservations. Americans against a navy didn’t want to rack up a lot debt for the young country and believed the British would be further infuriated. Ultimately, the situation in the Mediterranean began to force the issue. In early 1794, Barbary pirates, having signed a truce with Portugal and been paid off by the British, began to attack any American ship in full force. Finally, on Jan. 2, 1794, Congress decided to create “a naval force, adequate to the protection of the United States against the Algerine corsairs.” A committee was formed, and they recommended a fleet of six frigates be constructed or purchased. Congress approved the recommendations and on March 27, 1794, President Washington, signed “An act to provide a naval armament,” which established the U.S. Navy.

In order to spread the wealth and speed up production, the six original frigates were built simultaneously, on six different locations along the U.S. Atlantic coast. The following port towns were chosen as the building sites for the frigates: Philadelphia for United States; Baltimore for Constellation; Boston for Constitution; New Hampshire for Congress; New York for President; and Gosport (Norfolk, Virginia) for Chesapeake. By 1797, United States, Constellation, and Constitution were launched and ready for sea duty. Congress and Chesapeake were launched in 1799 and in 1800.

Meanwhile, on Oct. 2, 1799, the Washington Navy Yard was established under the direction of Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert and the supervision of Commodore Thomas Tingey, who served as commandant of the District of Columbia navy yard for the next 29 years. As the nation’s first navy yard and homeport, shipbuilding and ship fitting were the dominant activities in the early years. Twenty-two vessels were constructed at the Washington Navy Yard that ranged from 70-foot gunboats to the 246-foot frigate Minnesota. During the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard remained an important support facility and a strategic location in the defense of the nation’s capital city. As the British stormed Washington in 1814, Tingey ordered the navy yard burned so that the enemy could not capture the strategic location. Over the years, the Washington Navy Yard has underwent multiple functions from ordnance and technology to the production of 14-inch naval railway guns during World War I. The Washington Navy Yard is still in operation today, but consists mostly of office space.

On the issue of national security, the U.S. Navy continues to be the world’s leading maritime deterrent. During the War of 1812, Constitution’s victory over HMS Guerriere on Aug. 19, 1812, inspired a young nation to challenge the vastly superior Royal Navy. Constitution—homeported at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston—remains and is the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat and the world’s oldest sailing vessel still capable of sailing under its own power. During World War II, the American Navy defeated the Japanese Imperial Navy in some of the most decisive victories in naval history. On the Pacific front, the Battle of Midway changed the course of the war and victories at Saipan, Philippine Sea, Iwo Jima and Okinawa led to Japan’s surrender. In the Atlantic, nearly 7,000 U.S. Navy and British vessels landed close to 160,000 troops on the beaches of Normandy. The sacrifice and unparalleled success of the U.S. submarine force was a significant factor in the demise of the Japanese Empire. In the Atlantic, the U.S. Navy played a major role in countering and defeating German U-boots. During the Korean War, Navy ships supported the Inchon landings and the Chosin Reservior operation. In Vietnam, the Navy flew around-the-clock air strikes and close-support missions, blockaded North Vietnamese waters, successfully interdicted North Vietnamese maritime supply, and provided crucial gunfire support. The Navy’s “brown water” riverine forces also made significant contributions during operations on the waterways of Vietnam. In recent years, U.S. Navy ships were among the first to fire Tomahawk missiles into Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.

Finally, people have always been the most important part of the Navy. From the likes of John Paul Jones and John Barry to Chester Nimitz and James E. Williams, the Navy’s rich history lies within its people and their commitment to serve this great country. Today’s Sailors are no different. They are 100 percent on watch 24 hours a day, seven days a week—and have been for 247 years. Happy Birthday, U.S. Navy!

Today in Naval History

Before dawn on Oct. 4, 1943, USS Ranger (CV-4) (as part of an Allied task force) reached launch position undetected in northern European waters to attack German shipping in the enemy-held Norwegian port of Bodø. Shortly thereafter, the aircraft carrier launched 20 Dauntless dive-bombers and an escort of eight Wildcat fighters. A group of the dive-bombers attacked 8,000-ton freighter La Plata, while the rest continued north to attack a German convoy, severely damaging a 10,000-ton tanker and a smaller troop transport. In addition, they sank two German merchantmen. A second attack group (10 Avenger torpedo bombers and six Wildcats) launched from the deck of Ranger and destroyed an enemy freighter and a small coaster. They also bombed a German troop transport.

Later that afternoon, the Germans finally located Ranger, but of the three enemy aircraft that attacked, two were shot down and the other was chased away. The highly successful attack, dubbed Operation Leader, helped reduce shipments of iron ore that were supporting the German war machine. The task force, to include Ranger, consisted of a portion of the British Home Fleet, cruiser Tuscaloosa (CA-37), destroyers Forrest (DD-461), Corry (DD-463), Hobson (DD-464), Fitch (DD-462), and Capps (DD-550). During the operation, three naval aviators were killed in action and three were captured, taken as prisoners of war. None of the ships in the task force suffered any significant damage and only three aircraft were lost. Ranger’s air group received four commendations for its gallant efforts and a number of pilots were recognized individually for their achievements. Operation Leader was the only U.S. Navy carrier operation in the Arctic Circle during World War II.

Before the United States had entered the war, Nazi Germany had feared possible incursions by the Allies into northern Europe. In April 1940, German forces attacked the neutral nations of Norway and Denmark in Blitzkrieg fashion. In only a few months, the province of Nordland and most of the northern reaches of Norway had been invaded. On the evening of May 27, the Luftwaffe (German air force) bombed and destroyed most of Bodø, which encompassed an important airstrip and radio station where Allied forces were operating. In addition to a small number of Norwegian and British military casualties, 1,500 civilians were killed and nearly 3,500 others were rendered homeless.

After taking control of the area, the Germans established several air fields and Bodø became a vital port for German-controlled shipping in the region. Eventually, Germany garrisoned Norway with about 300,000 troops. Norway’s King Haakon VII, Prime Minister Johan Nygaardsvold, Norway’s pre-war government, and a contingent of military forces managed to escape to Great Britain and remained there for the duration of the war. Danish Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning surrendered to the Germans in just a few hours after his country was attacked for fear the enemy would bomb Copenhagen, as they had done with Warsaw, during the 1939 invasion of Poland. In spring 1940, the enemy-occupied northern European countries had to be abandoned by the Allies due to the Axis invasion of France.

Operation Leader and similar attacks demonstrated the U.S. and Allied commitment to liberate Norway. Armed with excellent intelligence derived from breaking the German’s Enigma code and from the Norwegian Secret Intelligence Service, the raid caught the Germans completely by surprise.

Cole Attacked

Guided-missile destroyer USS Cole (DDG-67), commanded by Cmdr. Kirk S. Lippold, was underway from Norfolk, Virginia, on Aug. 8, 2000, bound for the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Indian Ocean in company with frigate Simpson (FFG-56) and Military Sealift Command oiler John Lenthall (T-AO-189). Following operations with Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean, Cole steamed southward through the Suez Canal and joined Fifth Fleet, Oct. 10–11. While Cole refueled on the morning of Oct. 12 in Aden, Yemen, al-Qaeda suicide bombers detonated an explosive-laden boat directly against the port side of the ship. The blast killed 17 Sailors, wounded 37 others, and tore a 40-foot wide hole in the ship’s hull.

The 17 Sailors killed in the attack were Lt. j.g. Andrew Triplett, ETC Richard D. Costelow, EW1 Kevin S. Rux, HT2 Kenneth E. Clodfelter, EN2 Mark I. Nieto, EW2 Ronald S. Owens, OS2 Timothy L. Saunders, MS3 Ronchester M. Santiago, MSSN Lakeina M. Francis, ISSN Timothy L. Gauna, SMSN Cherone L. Gunn, ISSN James R. McDaniels, SN Lakiba N. Palmer, ENFN Joshua L. Parlett, FN Patrick H. Roy, FN Gary Swenchonis, Jr., and SN Craig B. Wibberley.

In the aftermath of the explosion, the crew of Cole fought tirelessly to free shipmates trapped by the twisted wreckage and limit flooding that threatened to sink the ship. The crew’s prompt actions to isolate damaged electrical systems and contain fuel oil ruptures prevented catastrophic fires that could have engulfed the ship and cost the lives of countless crewmembers. Skillful first aid and advanced medical treatment applied by the crew prevented additional casualties and eased the suffering of many others. Drawing upon their Navy training and discipline, the crew heroically conducted more than 96 hours of sustained damage control in conditions of extreme heat and stress. Deprived of sleep, food, and shelter, they vigilantly battled to preserve a secure perimeter and restore stability to engineering systems that were vital to the ship’s survival.

After initial repairs on Cole were carried out, the ship stood out of Aden. On Oct. 30, heavy lift vessel Blue Marlin loaded the destroyer on board and transported it to Pascagoula, reaching the Mississippi port on Dec. 13. Cole’s crewmembers were flown to Rhein-Main Air Force Base, Germany, and from there back to Norfolk. Cole’s Sailors were then put on convalescent leave through Dec. 1. The ship returned to the water on Christmas Eve and continued repairs and maintenance into 2001. After 18 months of upgrades and repairs, Cole departed Pascagoula for her homeport of Norfolk and gallantly returned to the fleet in full active duty status.

Naval Academy Established

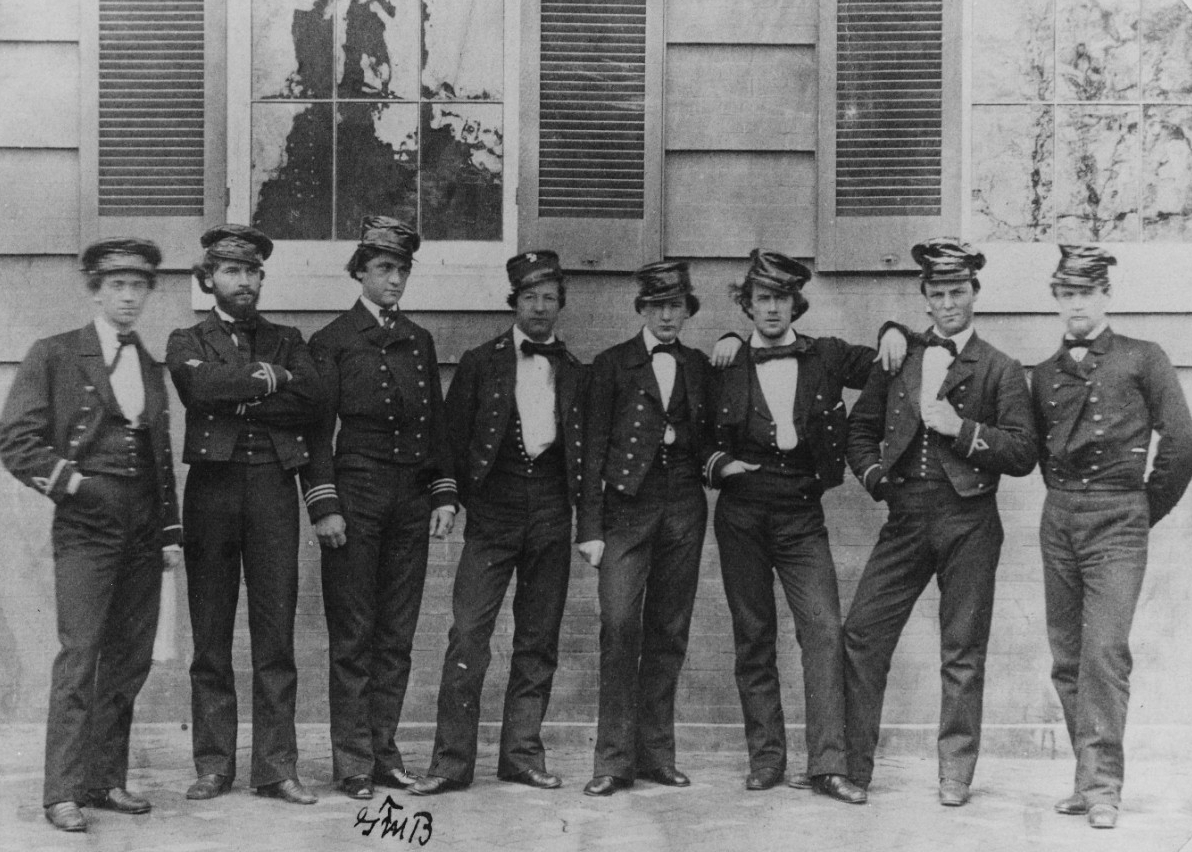

On Oct. 10, 1845, the Naval School—later the U.S. Naval Academy— opened in Annapolis, Maryland, with 50 midshipmen and seven professors. Through the efforts of then Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft, the Naval School was established without Congressional funding at a 10-acre Army post named Fort Severn. The school was originally planned for Philadelphia, but Annapolis was considered ideal because the government already owned the land, and Annapolis had a small-town atmosphere thought to reduce the temptations and distractions of the midshipmen. Cmdr. Frank Buchanan was selected as the school’s first superintendent.

In the early days, the daily routine included classes from 8 a.m. to noon and from 1:30 to 4:30 p.m. Meals and recreation lasted from noon to 1:30 p.m. and from 4:30 to 6 p.m. Study time was from 6 to 10 p.m. and lights out was at 10:30 p.m. There were two classes of midshipmen: oldsters (individuals who had already served at sea) and youngsters (newly appointed midshipmen). They were taught French or Spanish by Professor Arsène Girault, whose father had served under Napoleon. Mathematics and navigation were taught by Professor William Chauvenet, assisted by Passed Midshipman (passed exams, but not yet commissioned) Samuel Marcy. Natural philosophy (sciences) was taught by Professor Henry Lockwood, and history and English composition by Chaplain George Jones. Lt. James H. Ward, who also served as Buchanan’s executive officer, taught ordnance, gunnery, and steam, while Surgeon John Lockwood taught chemistry. Each student was required to give daily recitations, for which they were graded on a scale from 1–10. Weekly grades and merit standings were reported to the superintendent, and quarterly reports on each midshipman were forwarded to the Secretary of the Navy.

In May 1846, following the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, the school saw dramatic changes. Buchanan immediately volunteered for sea duty. Shortly after his departure, the government purchased his Annapolis home along with two adjacent properties in the first land expansion of the school. Ninety midshipmen, mostly oldsters, saw service in the war. Four midshipmen were killed in action. A monument that still stands today was later constructed to honor them. It was initially known as the Midshipmen’s Monument, but today is known as the Mexican-War Monument. It is the only physical feature on campus that survived from the early years of the academy.

In 1850, the school was renamed the U.S. Naval Academy, and a new curriculum went into effect requiring midshipmen to study at the academy for four years and to train aboard ships each summer. This curriculum is still in effect today. Milliard Fillmore was the first president to visit the academy in 1852. Capt. George S. Blake took command of the school in 1857. He would become the academy’s longest serving superintendent in office, serving for more than eight years.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, it was feared that Maryland could secede from the Union. In addition, the southern part of the Chesapeake Bay bordered the Confederacy. Therefore, it was decided to evacuate the academy to Newport, Rhode Island. On April 20, 1861, the 8th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment arrived in a large steamer with orders to protect frigate Constitution, which was carrying the midshipmen for transport to Newport. Several days later, SS Baltic arrived and transported the remaining staff, faculty, and their families, along with the school’s library and what laboratory and classroom equipment could be loaded. The academy grounds were turned over to the War Department for the use of landing troops and supplies to secure Maryland and to defend nearby Washington. The temporary relocation lasted until the late summer of 1865.

During World War I, a larger contingency of naval action was anticipated with mounting aggression by German submarines, and the number of midshipmen nearly doubled. In addition, the curriculum was reduced to three years, and there were no electives or majors. The Class of 1918 actually graduated in June 1917. The following month, the next class of plebes (freshmen) arrived in Annapolis, and among them for the first time were reservists. When midshipmen arrived back from their summer cruise in 1918, reports of an influenza pandemic, known as the Spanish flu, immediately followed. The superintendent of the school immediately imposed a quarantine, as there were already a few cases on campus. Of 2,118 midshipmen, at least 1,100 contracted the flu. In early October, 10 midshipmen and 18 members of the staff and faculty perished. Classes continued, but all extracurricular activities were canceled.

In 1933, Congress authorized the Naval Academy to begin awarding Bachelor of Science degrees. The academy later replaced the fixed curriculum with the present core curriculum plus 18 major fields of study, a wide variety of elective courses, and advanced study and research opportunities.

During World War II, the three-year course of study was adopted again, and civilian faculty members were given reserve officer status. Emphasis was placed on survival tactics and new technology, particularly anti-submarine warfare and radar. In addition, emphasis was placed on physical fitness and therefore a new athletic field (Sherman Field) was constructed. Academy alumni comprised 5 percent of the officer corps during the war. Twenty-seven alumni received the Medal of Honor for their actions in the Pacific.

Since then, the development of the U.S. Naval Academy has reflected the growing needs of the country. As America has changed culturally and technologically, so has the academy. Women now make up 20 percent of entering plebes. In just a few decades, the Navy moved from a fleet of sail- and steam-powered ships to nuclear-powered vessels, and the academy has evolved its curriculum to adapt to new technologies. The campus, once just 10 acres, is now 338. The original student body of 50 midshipmen has grown to a brigade of 4,000.