The Navy Department Library

History of the Navy Department Library

Origin

A single page letter from President John Adams to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, dated 31 March 1800, documents the establishment of the Navy Department Library. Adams asked Stoddert to establish a library for the Navy and "to employ some of his clerks in preparing a catalog of books for his office. It ought to consist of all the best writings in Dutch, Spanish, French, and especially the English, upon the theory and practice of naval architecture, navigation, gunnery, hydraulics, hydrostatics, and all branches of mathematics subservient to the profession of the sea. The lives of all the admirals, English, French, Dutch, or any other nation, who have distinguished themselves by the boldness and success of their navigation or their gallantry and skill in naval combat."

However, the library's roots extend back to 1794 when the Naval Bureau was part of the War Department in Philadelphia. In 1798 the Navy gained departmental status and the Secretary of the Navy was authorized to take possession of all the records, books, and documents relevant to naval matters that were then deposited in the office of the Secretary of War. This initial collection, subsequently evicted from its Philadelphia quarters by the War Department, found temporary refuge in a tavern in Trenton, New Jersey. When Washington became the national capital and the Department of the Navy moved there, wagons carried naval books and records while a schooner transported library furnishings to Georgetown.

Early Years

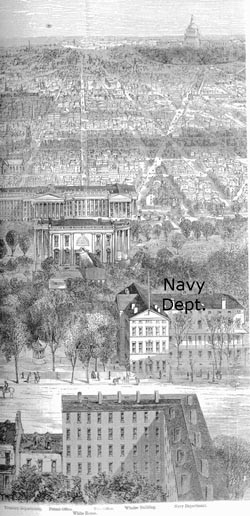

Although documentation on the library's early years is limited, the Navy's commitment to retain important books and documents is shown by the commandeering of wagons during the 1814 burning of Washington. Rushed to safety north of the federal city, the library's collection escaped the fate of other government libraries and agencies whose materials were destroyed or burned by fire. Following the War of 1812, the library's collection returned to Washington occupying part of a reconstructed two-story building known as the "Old Navy Department Building" at 17th Street between F and G Streets. In 1815 the department established the Office of the Commissioners of the Navy comprising three experienced post-Captains to assist the Secretary in the management of "matters connected with the naval establishment of the United States." Not to be outdone by the Secretary's Navy Department Library, the commissioners initiated their own collecting efforts. An 1823 document, Letter From the Secretary of the Navy Transmitting a List of Newspapers and Periodical Works, With a Catalogue of Books Purchased for the Use of the Navy Department, for the Last Six Years; and a Similar List and Catalogue for the Office of the Commissioners of the Navy provides a list of books and newspapers "purchased at the public expense" for both offices. When the commissioners' office was abolished in 1842, the library was distributed to the various bureaus "according to the nature of their duties." Many of these volumes later became part of the Navy Department Library.

The library's 1824 catalog indicates the collection totaled 1,349 volumes. The 1829 catalog reflects a decline in the number of books, but includes titles of the portraits, engravings and charts, then part of the collection. Some of these original volumes remain, but historical accounts report the transfer of portraits, engravings and charts to the Library of Congress. Catalogs and other library-related information for the period, 1830-1882, are difficult to document. However, manuscript catalogs are again in evidence in 1882, and reflect many of the titles in the 1824 and 1829 catalogs. In 1891 a printed catalog was published.

In 1879 the Navy's library moved to its most prestigious location, the State, War and Navy Building, later the Old Executive Office Building and now the Eisenhower Building at 17th and Pennsylvania Avenue. The library was housed in the Indian Treaty Room, richly decorated with marble wall panels, 800-pound bronze lamps, gold leaf ornamentation, and a frescoed ceiling studded with gold stars. At the time of construction, representatives of several leading European naval powers reported the work underway to their respective governments, leading several of these countries to send marble and other materials for the room's decoration, in recognition of the services of Union naval officers. This unique setting not only provided research services to the Navy and the secretariats but also served as a congenial meeting place for local leaders and foreign dignitaries.

Public Act No. 21 of 7 August 1882 officially established the library as a departmental institution. The act directed the head of each cabinet department to ascertain and report at the next session of Congress "the conditions of the several libraries in his department, number of volumes in each and plan for consolidation of the same so that there should be but one library in each department." Noted international lawyer and U.S. Naval Academy professor James Russell Soley accepted assignment as officer in charge of the newly consolidated departmental library under the Office of Naval Intelligence in the Bureau of Navigation. The exemplary qualified Soley began his tenure by gathering rare books, naval prints, and photographs scattered throughout the Navy bureau system, subscribing to professional and scientific periodicals, and classifying and cataloging diverse materials. More than anyone since President John Adams, Soley was responsible for envisioning and crafting the Navy Department Library.

In 1884, Navy Captain John Grimes Walker, Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, received initial funding for a project begun three years earlier to collect records of Union and Confederate naval operations for eventual publication. Even though Congress approved separate appropriations for the clerical staffs of the library and the war records project, Professor Soley supervised both activities operating under the title of "Office of Library and Naval War Records." These offices were transferred from the Bureau of Navigation and placed under the Secretary of the Navy's office in 1889 when Navy Lieutenant Commander F. M. Wise succeeded Professor Soley as librarian and officer in charge of war records. Soley's enthusiastic support and interest in the library continued even after his appointment that year as Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

In 1893, Navy Captain Richard Rush, who successfully published the first five volumes of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, succeeded Wise. This new organizational structure, combining a library, a record-keeping branch, and a mission to publish naval history, formed the basis of the present-day Naval Historical Center located in the Washington Navy Yard. The library joined the Federal Depository Library Program in 1895.

A feature article on the Navy Department Library appeared in the 26 February 1911 New York Herald under the headline "The Navy's Century Old Hall of Fame." Charles Stewart, library head at the time, provided insight into the evolution of the library and its collections, calling its growth over the past years "piecemeal and without any definite plan." At that time, there was no curatorial office within the Navy, so the library collected such items as John Paul Jones' sword, a fragment of the Penn Treaty Tree, and a block of wood from the chestnut tree that supposedly shaded Longfellow's village smithy.

Appropriations for compiling and publishing war records, and for the Navy Department Library remained separate until 1915, when on 4 March Congress combined and changed the title of the joint office to "Office of Naval Records and Library." Between 1917 and 1921 the Office of Naval Records and Library underwent two major organizational changes: first, the restoration of the library to the Office of Naval Intelligence from the jurisdiction of the Secretary's office (Navy Order 1 of July 1919); and second, the revival of its earlier historical functions which by the 1920s had almost ceased to exist.

During World War I, senior naval officers and their staffs, U.S. government and allied officials, news correspondents, and others depended heavily on the library for information on treaties, international law, and subjects related to the war. Frequent moves, including three during World War I, and the lack of professionally trained librarians were symptoms of insufficient space and inadequate staffing that persisted throughout the library's history. Even the Secretary of the Navy in his 1920 Annual Report acknowledged the need for professional library management.

". . .The Navy Library, which contains more than 50,000 volumes and many rare manuscripts, could be made of much greater value if a competent librarian were secured. The law at present provides for a chief clerk, and for years the work was conducted under the direction of that official, but the position has remained long vacant, owing to the small compensation offered, $2,000, and the impossibility of securing, at that salary, a competent and experienced man. . . . Organized under a competent librarian, the library would be able to furnish officials of the department and others engaged in naval work or research, complete references on any subject desired. These references should extend to books in other libraries on technical or naval matters. There is increasing demand from many sources for information of this character, and the Naval Library should be able to furnish it, and could easily do so if an experienced man who possesses a knowledge of naval history and affairs as well as of library methods is secured. . . ."

Smith and Snow's Historical Sketch of the Navy Department Library and War Records (1926), based on personal recollections of those who served in the library, documents the visits of many important government leaders and foreign dignitaries. It recalls that Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during 1897-1898, took an active interest in library matters. And as President, on one occasion, he telephoned the librarian from the White House to inform him "that the shades were drawn unevenly" and on another occasion that "growing plants should not be placed in the Library windows."

Main Navy Building

The Navy moved the majority of its offices to the Main Navy Building on 18th and B Streets NW in 1918. However, it was not until suitable space was provided in 1923 that the library was relocated. This move significantly enhanced the library's reference and research value to the Navy for it was once again in close proximity to a large number of Navy users. Retired Navy and Marine Corps officers continued to hold the position of Superintendent of the Library until 1931 when, as an economy measure, it was combined with the Officer in Charge of Naval Records and Library. Commodore Dudley Knox, a gifted historian who served as that officer from 1921 to 1946, strengthened and reinforced the Navy's commitment to its historic heritage and traditions.

A 1931 Washington Star article, highlighting governmental libraries, described the Navy Department Library as being a large, well-arranged library with more than 77,572 volumes, records and documents related to naval science, biography, and history. As World War II approached and the Navy expanded, space was once again a premium. The library was reduced in size, and its holdings transferred to the Navy Annex in Arlington, Virginia, the National Archives, and the Library of Congress. Only a small reference collection, with Mrs. Constance Lathrop as librarian, remained at the Navy Building.

In the postwar years the library slowly recovered from its wartime scattering. In 1949 the Office of Naval Records and Library combined with Office of Naval History to form the Naval Records and History Division under the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. This organizational designation was simplified in 1952 to the Naval History Division. The division including the library remained in the Main Navy Building where it had been consolidated just after the war.

Washington Navy Yard

The Main Navy Building, originally intended as a temporary World War I structure, was demolished in 1970, and numerous Navy commands and offices were relocated. Joining the Navy Museum and the Operational Archives, the Navy Department Library moved to Building 220 in the Washington Navy Yard during the summer of 1970. An organizational change in 1971 established the Navy's history-related activities, including the Navy Department Library, as a field activity under the Chief of Naval Operations. The Naval Historical Center, later reorganized, expanded, and renamed the Naval History & Heritage Command, is the result of that and subsequent administrative changes. The Library and most of the Command's activities came together in 1982, when they moved to their present location at the corner of Kidder Breese Street and Dahlgren Avenue across from Leutze Park. This historic building complex was named to honor Commodore Dudley W. Knox.

Although many library users were physically separated from the library after its move from the Main Navy Building, this situation was eventually improved by the employment of new information technology starting in the early 1990s. The library catalog is online, and the library posts numerous publications, documents and subject presentations on the Naval History & Heritage Command's Website. The library's collection continues to expand thanks to the installation of compact mobile shelving and materials acquired from Navy offices, private individuals, and organizations such as the Naval Historical Foundation. Significant holdings have been obtained from disestablished libraries (including Naval Air Systems and the Navy Judge Advocate General), as well as from libraries whose collections have been downsized (such as the State Department). The donation of the disestablished Time-Life reference collection used in researching their World War II book series was a major acquisition for the library. Older material in our collection are included in the National Union Catalog of Pre-1956 Imprints, a set of 754 volumes, compiled from 1968 to 1981. Over 13% of the book titles in the library are unique in the international OCLC (Worldcat) database.

The Navy Department Library has met many challenges in its history and will continue to seek creative and innovative approaches, utilizing new technology to provide improved reference services while protecting and preserving its unique collection of books, serials, and manuscripts.

[END]