Main Navy Building: Its Construction and Original Occupants. Washington, DC: A Naval Historical Foundation Publication, Series 2 – Number 14, 1 August 1970. [Copyright by Naval Historical Foundation].

The Navy Department Library

Main Navy Buildiing

Its Construction and Original Occupants

Table of Contents

[1] Foreword

[2] Main Navy Building – Its Construction and Original Occupants

[4] The Labor Factor

[6] The Occupants

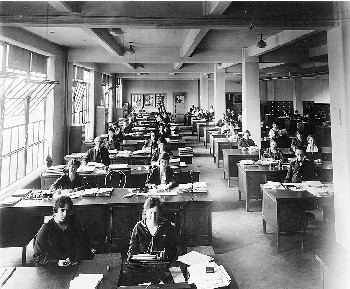

There are just a few “old-timers” who have had the pleasure of serving in the new Navy Building soon after it was built, especially in those years prior to the beginning of the build-up before World War II. Those were the years of the peacetime Navy. They were 1630 quitting time days, with afternoons off for golf or a good ball game when the Senators were tops. The duty in and the environment of Main Navy were pleasant even though not air-conditioned. The Navy cafeteria had good food and was the lunch hour haven for most officers, especially the more junior and budget conscious.

The Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations had nicely furnished adjourning offices on the second deck. Although not included in the original building, a private elevator was later installed for use by the Secretary of the Navy.

The General Board sat in its sacred space with the president occupying the historic desk of its former (first) President, Admiral George Dewey (The desk is presently in use by the President of the Naval Historical Foundation.).

The Bureau Chiefs (then appropriately named because they really were) could respond to a SECNAV or CNO call after only a short walk from their respective offices. Responsible officers were accessible and businesses were talked about rather than written about for decisions.

World War I yeomanettes, and, later on, those who had gone Civil Service, occupied many clerical positions. Most officers who did duty in the Department remember the all important Chief Clerks of the respective Bureaus—Curtis in SECNAV’s office, Cuthbert in the Chief of Naval Operations, Henkel in the Bureau of Navigation, with Draper (clerk, Naval Academy) and Wren in Steam Engineering.

Those were the days of the separate Navy Department, when the Navy fought its own battles on the “Hill.” Inter rather than intra-service problems prevailed. Main Navy was the citadel of the nation’s first line of defense. A challenging problem was confronted and resolved by experts mobilized by the push of a button in the offices of the Bureaus concerned.

Members with these fond memories will feel a pull on their hearts when they see the big ball swing against the walls of the Navy Building and see them come tumbling down.

Most of the text and many of the pictures are from the files of the Naval Facilities Engineering Command at Port Hueneme, California. The Foundation acknowledges the interest and cooperation of Mr. Leslie W. Walker, the Facility Historian, and also Mr. S.O. Goode, Director of the Facilities and Services Staff, Navy Department.

[2] Main Navy Building—Its Construction and Original Occupants

Early in 1900, it became apparent that the space in the stately structure adjacent to and west of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington, D.C., had become inadequate to house its long-time occupants, the Departments of State, War, and Navy. The latter two would have to find space elsewhere. Three years before World War I, the Navy had rented a nine-story building near the corner of New York Avenue and 18th Street. This was known as the Navy Annex and was completely occupied by the Navy. By July of 1917, however, the Department was occupying space in 21 different and widely separated buildings. This, of course, made intercommunication difficult and expensive. In addition, it delayed the increasing business of the Department arising from the impending war.

Expedients for taking care of the continued expansion and increased activities of the Navy Department were considered—renting, commandeering of finished or unfinished buildings, remodeling or “emergency” construction. At one point in August 1917, detailed plans for complete occupancy of the Arlington Building were on hand. The needs of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance put them aside. Another scheme formulated by the War Department, which was also being pressed for space, proposed taking the overflow of that Department and the Navy Department into a large block of temporary three-story frame and pebble-dash buildings at 6th and B streets. They were to have 800,000 net square feet of office area and to be known as the Henry Park Project. The Navy was given one-third of the area and $2,000,000 was appropriated by Congress on 6 October 1917. Construction started on 11 October, and Commander Parsons of the Bureau of Yards and Docks had the job of space assignment for the Navy. The building was finished in February 1918. By that time, however, the space demands of the Navy exceeded that allocated and available in the building. It was decided that placing the Navy Department in Henry Park was inadvisable.

In early 1918, it became apparent that the Navy had to carry its own load and arrange for enough space in a single building to meet its needs. The job was given to Bureau of Yards and Docks as the agency for “shore construction.” This was at variance with the orderly peacetime procedures where the Fine Arts Commission wields a controlling influence over public buildings under Congressional cognizance. Wartime demands and conditions set such precedents aside.

It was apparent that efficiency and economy demanded the housing of the Bureaus and offices of the Navy Department under a single roof. In addition, its activities, documents, etc., had to be quartered in fireproof construction. At that time, too, added criteria for a single building were speed in erection, indefinite occupancy and low costs. Of course, it was first necessary to find a suitable site. This was no easy matter. The War Department wanted to get in on the Navy Department project. This practically doubled space requirements. The Ellipse was discussed and abandoned after preliminary plans had been drawn. It is understood the President himself objected. A space south of the Tidal Basin was considered but found to be too inaccessible. The Monument Grounds seemed appropriate for an L-shaped building to the north and west of the Monument. High cost of grading and loss of many trees deleted this location from the picture.

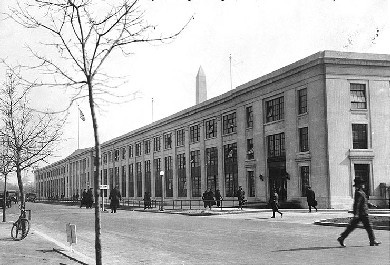

Finally, a tract in Potomac Park south of B Street and west of Seventeenth was discovered and selected. It extended 2,000 feet from Seventeenth to Twenty-first Streets and about 600 feet south from B. There was some initial objection to this site as interfering with the Lincoln Memorial ground development. This had to be waived. A contributing factor in the selection of this site was that it could be easily served with transportation. The trolley line being completed on Pennsylvania Avenue could be extended south via 19th Street southeast on Virginia Avenue and north on 18th Street to F Street. Also, a branch of the 14th Street trolley could be extended west of B Street to the 18th Street loop. The park eventually became the western extension of the Mall from the Capital to the Potomac River and the site of the Lincoln Memorial and the Reflecting Pool; B Street later became broad Constitution Avenue, which runs along the northern side of the Mall.

A question arose as to whether these buildings were to be considered as intended for “temporary” or “permanent” occupancy. Although they are commonly referred to as “indefinite,” it is a fact that the official title in the appropriation act authorized them as “temporary buildings.” A decision was also necessary as to the kind of construction to be used. Reinforced concrete seemed the best to meet all criteria. Fortunately, the Bureau was able to make a very clear case for its use in this project. Investigation showed the concrete structure could be built rapidly and at a cost not much above a full frame structure. Then, too, a reliable construction company had labor and skills for the work, and the Government itself had the wherewithal to obtain the needed material.

The project, thus developed, was laid before the Congress, in the Committee of the Whole of the House of Representatives, by Mr. Sherley, Chairman of the Committee on Appropriations on 15 February 1918. Discussions continued until the 18th, when an Urgent Deficiency Bill including appropriations for the project passed the House. The Senate amended the bill to provide for contracting for heating of the buildings and this amended bill passed the Senate on 12 March 1918. It was enacted into law on 18 March 1918. Even in those days there were “overruns” and, on 4 November 1918, a deficiency appropriation of $1,490,000 was enacted.

Paragraph Authorizing Construction of War and Navy Department Buildings, From Pages 65 and 66 of H.R. 9867, Urgent Deficiency Bill as it Passed the Senate on March 12, 1918.

TEMPORARY OFFICE BUILDINGS.

For two three-story temporary office buildings of reinforced concrete with wings sixty feet wide, and for the Navy Department to contain approximately nine hundred and forty thousand square feet and one for the War Department to contain approximately eight hundred and thirty-five thousand square feet, to be erected under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy in Potomac Park west of Seventeenth Street and south of B Street, beginning with the Navy Department Building at a point not less than two hundred and thirty-five feet west of the westerly curb line of Seventeenth Street and fifty feet south from the southerly curb line of B Street and extending southerly not more than six hundred and twenty feet from the said B Street curb line and westerly to a point not beyond the easterly building line of Twenty-first Street, including electrical equipment and a temporary heating plant for both buildings, to be located south of D Street and west of Twenty-fifth Street, with necessary connecting mains, $5,775,000(65): Provided, That the Secretary of the Navy is authorized to contract for the heating of the buildings authorized in this paragraph in lieu of the erection and operation of a heating plant authorized therefor, if in his discretion the contracting for said heating is more economical and to the best interests of the Government.

Paragraph Making Deficiency Appropriation for Completion of War and Navy Department Buildings, From Urgent Deficiency Act of November 4, 1918. Public No. 233, 65th Congress (H.R. 13086), Page 15.

TEMPORARY OFFICE BUILDINGS.

For the completion of the two temporary office buildings authorized by the deficiency appropriation Act, approved March 28, 1918, to be erected in Potomac Park for the use of the War Department and Navy Department, $1,490,000.

The original appropriation provided for two concrete buildings with 940,000 square feet for the Navy Department, and 840,000 square feet for the Army; figured on a basis of $3.31 per square foot. The overrun resulted from additional piling, linoleum covered decks, and increased labor costs. At the time of erection, these buildings had a greater area of available floor space than any other office building constructed up to that time. The 41-story Equitable Building in New York had only 1,700,000 square feet and took 20 1/2 months to build, whereas these buildings went up in 5 1/2 months.

The Turner Construction Company of New York, a concern familiar with reinforced concrete work on a large scale, was given the general contract for this work on 25 February 1918 on a cost plus fixed fee basis. They erected their two-story 220x30 feet construction office at 19th and B Streets. The advanced work force and Navy personnel moved into the building and the subcontractors for heating, plumbing and electrical work, etc., built a joint office for their personnel. The chronology of the events leading to the construction of these buildings is of interest, in view of present day thinking and planning:

(a) Preliminary studies, January and early February 1918.

(b) Date of contract, work started 25 February 1918.

(c) Elaboration of plans, February thru April.

(d) Granting of appropriation, 28 March 1918.

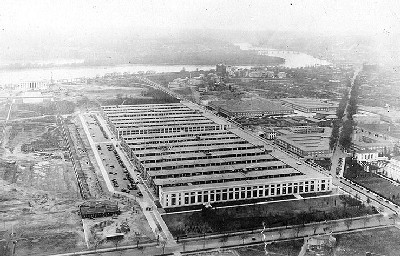

Two buildings were built; one known as the Navy Building, the other the Munitions Building. They are connected by a covered bridge spanning the 100 foot roadway separating them. Each building is to be three stories high, with structural framework of reinforced concrete with gypsum board and plaster partitions, steel sash and brick curtain walls. The latter to be omitted on the exposed front, where two-storied window treatment is used. The concrete surface is finished with a white cement and sand mixture rubbed in by hand. There are nine parallel wings in the Navy Building and eight in the Munitions Building. Each is 500 feet long and 60 feet wide, connected in the front along B Street by a so called “head house” 60 feet wide. There is a 40 foot court between each wing which is crossed by two covered gangways at the second deck level.

Although intended to be “temporary buildings,” it is interesting to note that the upper floors are of reinforced concrete, designed to support a live load of 75 pounds per square foot, and are finished with a wearing surface of concrete. They are 3 1/2 inches thick, with one-way reinforcement of 3/8-inch rods spaced 6 inches, center to center. Columns are spaced 20 feet apart throughout; interior columns are 18 by 18 inches in section; wall columns 13 1/2 by 28 inches. The first story is 12 feet 6 inches in height, floor to floor, the second and third, 12 feet each. Column reinforcement consists of four 1 1/8-inch rods. Girders are 12 by 20 inches by 20 feet in span, reinforced with five 1 1/8-inch rods, while beams are spaced 6 feet, 8 inches, center to center, and have 3-rod reinforcement and a second of 8 by 14 inches.

The staircases were all reinforced concrete. There are four in each head house and two or three in each wing. Two electrically operated freight elevators are provided in each building. A suspended ceiling of gypsum board and plaster extends over the entire upper floor at a height of eleven feet.

Soon after the preliminary work was started, it was found that the area on which the buildings were to stand overlaid a portion of the old riverbed. This made added piling necessary and was one reason for the cost “overrun.” To reach solid ground requiring piling varying from 20 to 52 feet. Two different kinds of piling were necessary, concrete (cast in place within predriven shells) and so called “composite” (wooden pile surrounded by one of concrete). Between 25 March and 28 May, 5,048 piles were driven. Four drivers were operated continuously 24 hours per day including Sundays. Piling follows the lines of the outside walls over practically the whole area. This unexpectedly large pile driving requirement did not delay the occupation by more than 30 days.

The contractor, realizing the amount of concrete to be poured and the necessity for a speedy completion, devised a construction plant which met the conditions. A heavy trestle was built paralleling the entire length of the site (2,200 feet) at the rear, 17 feet in height, and having approaches from the street level with a gradient of 11.8 per cent. This trestle was designed to carry 5-ton motor trucks, which brought sand and gravel from nearby river dredgings, and cement in bags from a railroad siding adjacent. Eight storage units for this material were placed at intervals underneath the trestle, each provided with separate bins for 55 cubic yards of sand, 110 cubic yards of gravel, and a suitable supply of cement. The aggregate bins were covered by gratings of 4 by 12-inch planking, set on edge and spaced 4 inches apart. Over the trestle a fairly steady processing of trucks passed from east to west, dumping sand or gravel through the proper gratings or delivering sacked cement through chutes for storage as needed.

The mixing plants were located midway in alternate courts of the building under erection. Each was connected with one of the storage units by a straight track of narrow gauge at right angles to the trestle and about 300 feet long. Upon these tracks ran small cars of the industrial type, having separate compartments for sand and gravel, and controlled by an endless rope from a motor at each mixing plant. Brought to a stop under the trestle, they were automatically loaded with sand and gravel in proper quantities from the bins, and, cement being then thrown in on top, they were ready for the return trip to the mixer.

Each mixing plant comprised a 1 1/4 yard mixer sunk below ground level, a 40-horsepower electric motor for its operation, and a tower hoist for the distribution of the mixture.

Concrete was delivered to place in two-wheeled buggies, operating at four levels from platforms adjoining the towers, no chuting was employed at any stage. The capacity of each mixing and distributing unit, with 50 hands each, was 400 cubic yards per day, restrictions as to quantity of dry material having been eliminated by the system already described. Since each plant was entirely independent of the rest, the theoretical maximum capacity on the job was 3,200 cubic yards of concrete per 10-hour day, though practical conditions kept the recorded maximum down to 1,750 yards, equivalent to a section of the building 300 feet long.

The placing of the structural concrete was accomplished in 13 1/2 weeks from April 5, 1917, an achievement which is thought to have established a record for this type of work. The weekly output was equivalent to a 780-foot section of the structure, while the total yardage of concrete employed on the job was 68,000. Concreting of the ground floor was a separate constructional operation and one of the last performed. This floor is of concrete six inches thick over a puddled and rolled fill of earth and cinders, with a wearing surface similar to that of the upper floors.

It is not to be supposed that the construction of these immense buildings proceeded by definitely separated steps. Such a thing would have necessitated sudden and complete replacements of large bodies of workmen as the character of the work changed. Rather, the progress of the project was a development proceeding in general from east to west. Concreting overlapped pile driving and at last displaced it; roofing had been placed on the first wing before form work was complete on the last; bricklaying followed the advance of the concrete frame; partitions were being constructed on the upper floors before the ground floor had been laid.

The floors of the Navy Building were subdivided to meet the particular needs of the various bureaus. A suite of rooms assigned to the Secretary of the Navy and his staff had an individual treatment. Ornamental plaster cornices decorated rooms, special fireplaces, mantels and cork tile floors were installed.

Originally, an entire wing of the third floor was fitted as a cafeteria to provide service for 1300 patrons at one time. It was equipped with the most modern mechanical cooking devices and other facilities patterned after the large cafeterias in industrial institutions.

The heating was insured by the installation of 3,200 radiators, 27.4 miles of heating pipe, and 2,800 plumbing fixtures. A low-pressure vacuum-return steam system was used. Live steam and electric power and light were furnished by The Potomac Electric Power Company about one mile distance from the building. For heating, the contract price was based on coal costing $5.00 a ton.

The telephone system for the building was controlled from a large exchange in the 5th wing of the first floor. Also included was a branch office of the city post office equipped in every detail to handle, even at that time, the enormous amount of daily mail.

A suitable floor covering for the cement decks was a problem. Finally, 3/4” thick solid brown linoleum was chosen. The contract to supply and lay it added $325,000 to the cost. Laying began in January 1919, and 75 men worked until May of that year at which time 29 acres out of the 41 were covered. Corridors and certain special areas were left uncovered.

A macadamized space in the rear of the building “to accommodate a large number of automobiles” was provided to park 500 cars. There were gateways at various places and tall wire fencing enclosed the space attended by guards.]

The maximum construction force on the buildings, including both skilled and unskilled labor in the employ of the general contractor and all subcontractors, was approximately 3,400 men, of whom approximately 1,600 were carried as common labor. This maximum was maintained through June and July, 1918. Workmen of all the building trades were employed in numbers unequaled by any previous job of the kind in the District of Columbia. Speed was a primary consideration in the work, and its wide distribution made possible the effective employment of many large independent gangs.

The contractor brought to bear every worthy incentive on his workmen of all ranks to maintain a high standard of output. To this end, inspirational and “welfare” activities of a variety adapted to conditions were carried on throughout the life of the job. Graphic charts were exhibited showing the weekly progress of construction. Records of conspicuous gangs were posted and higher records encouraged. Frequent opportunities were afforded for the entire personnel to assemble in rallies and mass meetings at midday or in the evening. A patriotic spirit was fostered at such gatherings by means of addresses by persons of prominence, singing of popular airs, band music, and the like. Evening entertainments such as boxing bouts, pie-eating matches, and dancing competitions proved helpful in maintaining a degree of morale. An illustrated paper abounding in cartoons, portraits of noteworthy gangs and individuals, personal references, and items of project news was issued weekly. An illustrator of proven ability was engaged to reside on the job and produce posters, and other pictorial work for the stimulation of enthusiasm. A “job flag,” displaying an eagle poised on a broom, was designed by him and flown during working shifts. The sale of war savings stamps was pushed with considerable publicity. As was aptly stated, “these were intended to build a fire under the tail of progress and scare the beast into a gallop.”

But economic conditions at the time were such as to offset a great volume of inspirational and welfare work. Common labor caused the greatest concern, beginning about the middle of May to develop a pronounced migratory tendency, which was simply a reflection of the workers’ unrest affecting the entire country. Rates of pay for unskilled labor on this job started at 30 cents an hour and increased rapidly to 44 cents in order to compete with the New York market. Railroad fare and expenses were paid for incoming workmen and return fare for the minority who continued at their tasks until completed.

Little difficulty was experienced in securing common labor up to the time the gang reached 1,000, and during the first ten weeks of the project, up to 15 May, it was necessary to employ only 12 per cent more hands than were actually at work. On that date, owing to increasing unrest, the ratio of men hired to men employed took a sudden jump. During the life of the job 7,500 common laborers (principally Negro) were hired by the general contractor to recruit his labor gang, which never included more than 1,500 or 1,600 men at any one time. Keeping up the average force at this number for a period of seven weeks necessitated the hiring of 2,800 men, after 3,400 had already been sifted to establish the initial gang of 1,500.

As the work progressed, it was soon found necessary to build barracks and provide a commissary to take care of the men as they came in. Accommodations for nearly 1,200 men were provided, the barracks serving not so much as a permanent abode as a transfer station pending the location of the laborers in other lodgings. These quarters were crowded to capacity, during the height of construction, with the transients and such others who chose to keep up a longer occupancy.

The space assigned in the Navy Building was approximately:

Operations—17%

Navigation—17%

Supplies & Accounts—17%

Steam Engineering—11%

Construction & Repair—9%

Yards and Docks—8%

Ordnance—6%

Secretary’s Office—5%

Medicine & Surgery—3% *

Corridors—3%

Lunch Room—3%

Compensation Board—1%

General Board—1%

Judge Advocate General—1%

Solicitor—1/2%

Consulting Board—1/2%

*A very complete First Aid Station was fitted on the B Street end of the 9th wing within the space assigned to Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

The following offices were not initially moved into the Building:

Dispensary—Corcoran Courts

Navy Red Cross—Corcoran Courts

Examining Board—Corcoran Courts

Retiring Board—Corcoran Courts

Hydrographic Office—Navy Annex

Marine Corps—Navy Annex

Coast Guard—Munsey Building

Navy Records & Library—State, War, & Navy Building

The dates on which important phases of the project were begun and completed are given in the following list:

Contract signed and work commenced on site—25 Feb. 1918.

Appropriation granted—28 Mar. 1918.

Pile foundation decided on—9 Mar. 1918.

First pile driven—25 Mar. 1918.

Last pile driven—28 May 1918.

Concreting started (footings)—5 Apr. 1918.

Concreting finished—27 July 1918.

Moving in begun (Navy Department)—17 Aug. 1918.

Moving in begun (Munitions Building)—31 Aug. 1918.

Bureau of Yards and Docks moved in—1, 2, & 3 Oct. 1918.

Occupation complete—Early Oct. 1918.

A bill of materials for the project, if drawn up in a single document would have included the following items:

Steel reinforcing bars, 4,500 tons.

Eight and one-half acres of steel sash.

Twenty thousand separate window shades.

Roofing felt, 3,000,000 square feet.

Nails, 8 carloads; lumber, 314 carloads—7,500,00 feet; glass, 18 carloads; putty for same, 3 carloads.

Radiators, 3,200; heating piping, 27.4 miles; plumbing fixtures; 2,800.

Trenches, 14 miles.

Lighting fixtures, 15,000.

Outlet boxes and fittings, 50,000.

Push buttons, 5,000.

The area occupied by halls, toilets, stairways, etc., is 22 per cent, or 390,000 square feet, leaving net office area of 1,390,000 square feet. Total cubic contents of both buildings is 25,000,000 cubic feet. The prism inclosing the buildings is 1,744 feet long by 561 feet wide, with a height of 40 feet.

There was no cornerstone laid for the Building, nor were any dedication ceremonies held. At the time they were built, they were constructed of enduring materials, and on foundations of a most permanent character. In respect to their arrangements for light and air for office purposes, they were better than any permanent building in Washington. An elevator was installed when Secretary Swanson occupied the Secretary of the Navy’s suite. During World War II, a fourth floor was added to all wings, and a zero wing was built on the 17th Street end of the building. In addition, War and Navy Buildings were erected in the rear of the main building, and L, K, J, and I buildings across the reflecting pool, plus T-3, 4, and 5 along Constitution Avenue across 17th Street.

The Navy Department Telephone Directory of 1 November 1918 was a 5 1/2”x9” paperback booklet. The “Alphabetical Section” listed about 1,650 phone numbers with double-spaced names, offices and departments, and room numbers totaling 32 pages. The “Classified Section” had 38 pages, double-spaced, and showed the same information alphabetically arranged by Bureau and Department.

It is interesting to note the organization and space assignments of the occupants of the new Navy Building on this date. Rear Admiral D.W. Taylor was the Chief of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, which listed 175 names. He was in room 2000. The blueprint room was 2236 and the library 2206. The Aircraft Division, with Captain H.C. Mustin and Lieutenant Commander Hunsaker on its list of 65 people, was on the 2nd wing of the 3rd deck. Contract Division had two people listed in 2004. Design was in the first wing of the 2nd deck. It had 40 people listed, among them Commander E.S. Land as Submarine and Commander Van Keuren as Battleship designers. Captain W.F. Halsey, the father of Fleet Admiral Halsey, was in 2107. Commander J.A. Furer, head of Office of Naval Research in World War II and author of The Administration of the Navy Department in World War II, was listed as head of both Maintenance Division and Supply Division.

The General Board, with four Rear Admirals and their secretaries, occupied rooms 2749, 2743, 2741, 2750, 2746, 2748, 2745, and 2747.

Rear Admiral W.C. Braisted, father of our longtime member Rear Admiral Frank Braisted, was Chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. He was in room 1066. It had 43 persons listed and they occupied rooms in the 8th and 9th wings of the 1st deck. The Naval Dispensary was in Corcoran Court. Rear Admiral C.T. Grayson, the White House physician, was in charge of the 16 persons listed in the book. The Dental Section, General Emergency Office, and Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat were also there. The Naval Hospital and Medical School were at foot of 24th Street. There were 20 officers of the Medical Corps listed at the hospital with Rear Admiral R.M. Kennedy in command.

The Chief of Naval Operations was Admiral W.S. Benson in room 2050. The Assistant Chief was Captain W.V. Pratt in 2056. He was also head of the Planning Division which had eight other officers, including Captain H.E. Yarnell, Captain Waldo Evans, and a clerk in 2064. The Antisubmarine and Destroyer Sections each list one officer. The Submarine Section had four officers, among them Captain T.C. Hart and Commander C.W. Nimitz together in room 2707. Material Division had 11 officers in the 5th wing of the 1st deck; listed were Rear Admiral J.S. McKean as head in room 1050, Captain C.C. Bloch in room 1052, and Captain J.M. Reeves in 1060. Armed Guard Section had two officers in 1062, Naval District Section with 13 officers in the 6th wing of the 2nd deck, together with Naval Overseas Transportation Section’s 14 officers in the same area. Aviation Division was headed by Captain N.E. Irwin in 3426, and the 48 officers were in the 4th wing of the 3rd deck; among them were Lieutenant D.R. Goldthwaite (Training) 3410; Lieutenant Commander A.C. Read (Material) 3411; Captain G.W. Steele, 3405; and Commander J.H. Towers (Senior Assistant) 3409. Naval Communication was the largest division in the Chief of Naval Operations. It included Cable Censor and Communication Office and occupied the 6th wing of the 1st and 2nd decks. Gunnery Exercises and Engineering Performances with Captain W.D. Leahy as Director and 10 officers were in 3642, 3649, 3650, and 3551. There were 280 listed phones in the Chief of Naval Operations Section of the book.

Naval Intelligence had Rear Admiral Roger Welles as Director and 64 other persons listed in the 7th wing of the 1st and 2nd decks.

Bureau of Navigation had Rear Admiral L.C. Palmer as its chief in room3052. The Planning Section listed two officers with a conference room in 3056; the Training Section’s eight officers were in 3064. There were 33 persons listed in the Officer Personnel Division in the 6th wing of 3rd deck, with Captain W. McDowell as Chief Officer and 64 persons in Enlisted Personnel Division in the 7th, 8th, and 9th wing of the 3rd deck, with Captain J.K. Taussig as Commanding Officer.

Bureau of Ordnance had Rear Admiral Ralph Earle in 3149. Armor and Projectile Section had four officers in 3105; Aviation Ordnance had 22 in the 2nd wing of the 3rd deck. There were actually 30 sections of varying sizes in the Bureau of Ordnance organization with a total of 160 officers; among the names appearing as Chief of the Special Board on Naval Ordnance was Rear Admiral R. R. Ingersoll, father of the present Admiral Ingersoll. They occupied the 1st and 2nd wings of the 3rd deck.

Secretary of the Navy’s office was in room 2046 with additional offices along the main corridor of the 2nd deck and the 5th wing of the 2nd deck. There were 42 persons listed in the Secretary of Navy’s office, and 14 in the Compensation Board in the 4th wing of the 2nd deck.

The Judge Advocate General was Rear Admiral George R. Clark in 2550, with 45 persons in the 5th wing of the 2nd deck. In addition, there were 16 in the Solicitor’s Office in the 6th wing.

The Chief of the Bureau of Steam Engineering was Rear Admiral R.S. Griffin in 2029. The Aeronautics Section had 37 persons in the 3rd wing of the 3rd deck, and along the main corridor; Commander A.J. Atkins was in charge. Design was in the 3rd wing of the 3rd deck and had 19 persons in it. Rear Admiral C.W. Dyson was in charge. The Electrical Section was the largest with 39 people in the 3rd wing on the 2nd deck. Radio Telegraphy was headed by Commander S.C. Hooper, with 24 persons in the 4th wing of the 2nd deck. All told there were 194 persons in this Bureau.

Bureau of Supplies and Accounts had Rear Admiral S. McGowan as the Chief of Bureau in room 1000. The Accounting Division was in the 4th wing of the 1st deck with 51 people. The Purchase Division was the largest in the Bureau with a total of 120 and with Commander J.M. Hancock as Officer in Charge. It occupied wings 1 and 2 of the 1st deck.

Bureau of Yards and Docks had Rear Admiral C.W. Parks as the Chief in room 2083. The Design Section was the largest with 59 and occupied the 9th wing of the 2nd deck. There were 120 persons listed in the BUDOCKS phone listing.

[END]