Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

In the late morning of Oct. 18, 1812, American sloop-of-war Wasp, commanded by Master Commandant Jacob Jones, finally caught up to an enemy convoy that his ship had been following since the night before, consisting of six merchantmen under the protection of British 22-gun Frolic. At approximately 11:30 a.m., Wasp and Frolic closed in for battle, commencing fire at a distance of 50–60 yards. In a short, but violent clash, both ships sustained heavy damage to their masts and rigging. Wasp ultimately prevailed when the American crew boarded the English vessel in hand-to-hand combat. Shortly thereafter, 74-gun ship-of-the-line Poictiers arrived on the scene. Subsequently, Jones was forced to surrender to Poictiers because he was unable to escape or even put up a fight against the vastly superior, undamaged enemy ship. After Wasp was captured and Frolic recaptured, Jones and his crew were taken as prisoners of war, but a few weeks later, they were released in a prisoner exchange. Wasp later served with the British as HMS Peacock until it was lost off the Virginia Capes in 1813. Although Jones had lost Wasp, the achievement of capturing Frolic was highly celebrated among his countrymen. Upon his return to the United States, Jones received a sword from the State of New York and a Gold Medal from Congress, was promoted to captain, and given command of frigate Macedonian. Regrettably, Macedonian, for the duration of the War of 1812, was blockaded off New York and saw no combat action. In the last year of the war, Jones was transferred to Lake Ontario where he commanded frigate Mohawk. At the direction of Commodore Isaac Chauncey, Mohawk was instrumental in the control of the lake during the crucial Niagara campaign of 1814.

Born in March 1768, Jones was the son of a well-respected farmer in Smyrna, Delaware. Although his parents died when he was young, Jones was able to embark on an education in medicine, first under local doctor and politician James Sykes and later at the University of Pennsylvania. After initially practicing medicine, Jones decided to switch careers to law, and Delaware’s Federalist Governor Joshua Clayton appointed him as the clerk of the Delaware Superior Court. He married the daughter of his former mentor, Dr. Sykes, who tragically left him a widower before Jones entered the Navy in 1799. During the Quasi-War with France, Jones’ served under Commodore John Barry on frigate United States and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in 1801. Jones was an officer on frigate Philadelphia when that ship was taken by the Tripolitans in 1803. Held captive for nearly two years, he again joined the seagoing service after his release, and with the rank of master commandant, took command of Wasp in 1810.

After America’s second war with Britain during the final Barbary engagement, Jones once again was given command of Macedonian in 1815. On May 20, the ship departed for the Mediterranean to join Commodore Stephen Decatur’s 10‑ship squadron to stop the harassment of American shipping. On June 17, his frigate assisted in the capture of Algerian flagship Mashuda, and subsequently, the signing of a treaty with Algeria in June and Tunis and Tripoli in August won maritime freedom in the Mediterranean. In 1821, Jones assumed command of the Mediterranean Squadron, and in 1824, was appointed to the Board of Navy Commissioners. Two years later he became commander of U.S. Naval Forces in the Pacific. At the time of his death, Aug. 3, 1850, Jones held the position of commandant at the Naval Asylum in Philadelphia.

The U.S. Navy has named two destroyers and an escort ship in honor of Jones—USS Jacob Jones (Destroyer # 61), 1916–1917; USS Jacob Jones (Destroyer # 130), 1919–1942; and USS Jacob Jones (DE-130), 1943–1973. Notably, the first ship named for Jones, Destroyer # 61, was sunk in the Irish Sea during World War I by German U-boat U-53. Sixty-four of the crew were lost. Ironically, the second ship named for Jones, Destroyer #130, was also sunk by a German U-boat, U-578, during World War II. Most of the crew were lost as a result of the enemy submarine attack.

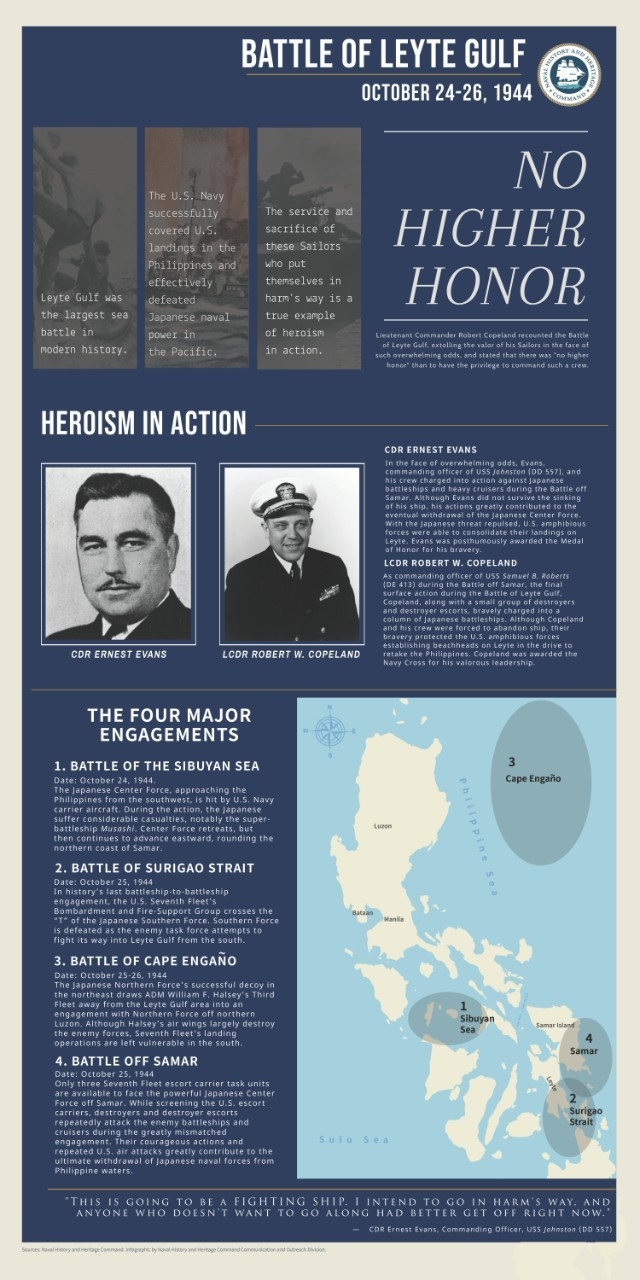

Battle of Leyte Gulf

On Oct. 23, 1944, the Battle of Leyte Gulf commenced with U.S. submarines attacking two elements of the Japanese armada moving towards Leyte. In the Palawan Passage, USS Darter (SS-227) and USS Dace (SS-247) sank heavy cruisers Maya and Atago. Takao was also attacked, but ultimately survived. In addition, off Manila Bay, USS Bream’s (SS-243) torpedoes heavily damaged Japanese cruiser Aoba. The battle, which lasted until Oct. 26, crippled the Japanese Combined Fleet, reinforcing the U.S. invasion of the Philippines and the Allies control of the Pacific. The Battle of Leyte Gulf made good on Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s promise, “I shall return,” to retake the Philippines after it was lost in the early stages of World War II.

The goals of the Allied offensive were threefold: sever Japan’s supply lines to the East Indies; soften the battlefield for the invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) and the east China coast; and provide bases for an attack on the Japanese home islands. In early September, Adm. Marc Mitscher’s fast carrier task force began to launch attacks against Japanese positions in the Philippines. On Sept. 21, U.S. aircraft struck Manila for the first time and Luzon was attacked the following day. On Sept. 24, Mitscher’s air assets bombed the central Philippines and conducted photographic reconnaissance of the areas of Leyte and Samar where the initial Allied landings were planned. Originally, the massive attack on the Philippines was planned for a later date, but Mitscher’s airstrikes revealed unexpected weaknesses in the Japanese defense of the islands. The Joint Chiefs of Staff swiftly moved to capitalize on the Japanese vulnerability. The timetable was revised and an amphibious assault was scheduled for late October. Leyte was deemed vulnerable from the east and had great access to other islands in the archipelago. Moreover, the seizure of Leyte would isolate Japanese troops in Mindanao. The assault on Leyte also marked the merging of two major advances—Adm. Chester Nimitz’s central Pacific offensive and MacArthur’s southern Pacific approach. MacArthur was given overall command of the Leyte operation while Nimitz provided naval support from Adm. William Halsey’s carrier-based Third Fleet. Preparatory strikes began in early October on the Ryukyu Islands, northern Luzon, and Formosa. After the battlefield was prepped, more than 130,000 troops from the Sixth Army stormed ashore on the first day of the invasion. The invasion was mostly uncontested in the early phases of the battle due to the Japanese opting to mount their defense further inland out of range of naval gunfire. Part of the Japanese plan to defend Leyte, dubbed Sho-Go (Operation Victory), was to decoy Third Fleet north away from the San Bernardino Strait while converging forces to counterattack American forces.

Just after midnight on Oct. 23, the Allies began the early stages of the attack. Initially, Darter and Dace shadowed the Japanese armada, reporting back to the Pacific Fleet their speed, heading, and makeup. When dawn finally broke, the submarines made their first visual contact and launched torpedoes. Eventually, Darter was run aground and eventually destroyed by Japanese aircraft, but not before the crew was safely transferred to Dace.

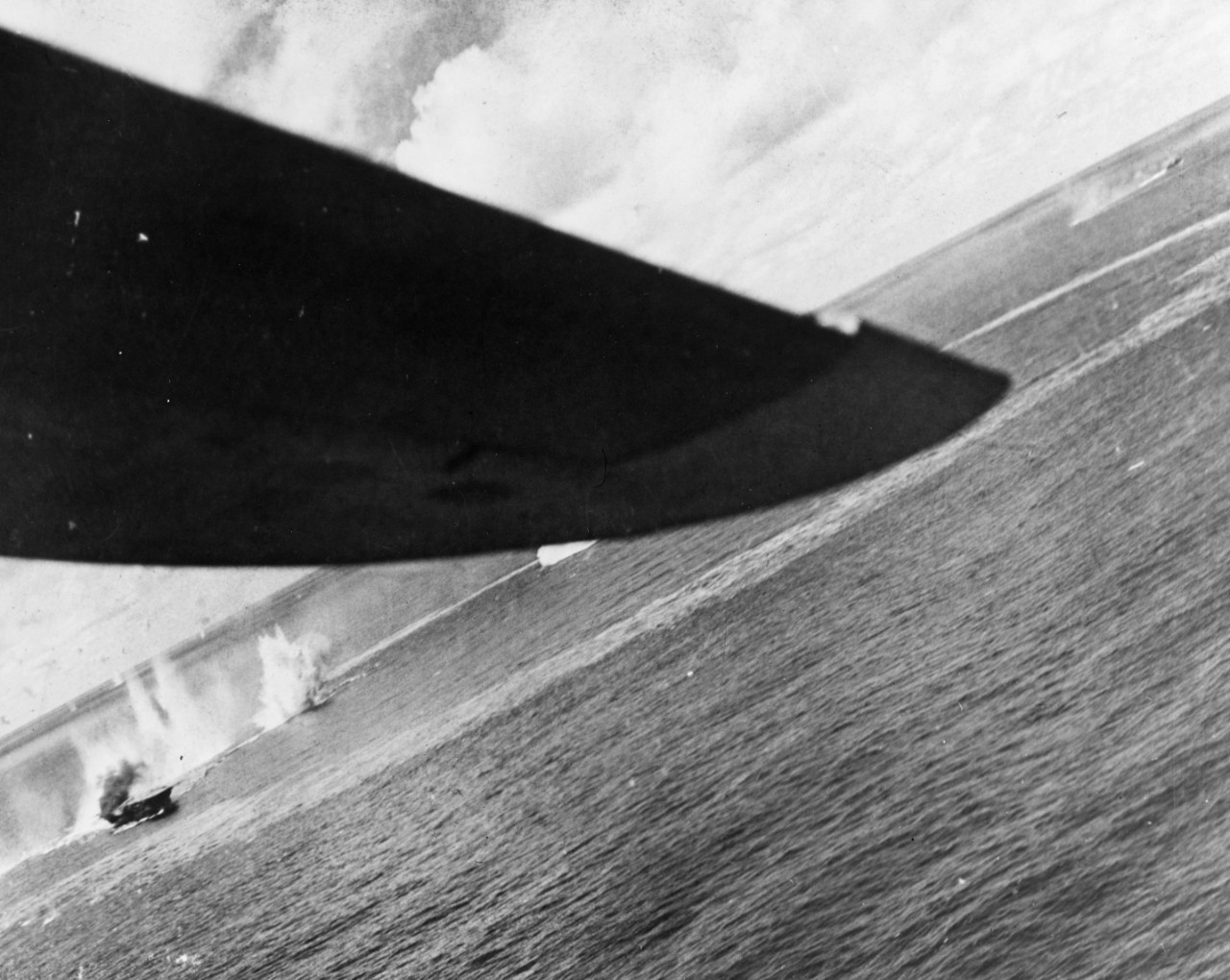

The following day, aircraft from Third Fleet located and attacked the Japanese central force in the Sibuyan Sea and the southern force in the Sulu Sea. In the Sibuyan Sea, several Japanese vessels were damaged and battleship Musashi was sunk. Early in the fight, aircraft carrier USS Princeton (CV-23) was struck by a 550-pound bomb from an enemy dive-bomber that ignited fires on multiple decks. Allied destroyers and cruisers descended on the stricken ship in an attempt to save the crew and the carrier. Rescue and repair efforts continued throughout the day. Just before 3:30 p.m., a massive explosion ripped through the crippled carrier, killing hundreds on the ship as well as crewmembers on cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-62) that were preparing Princeton for tow. Eventually, Princeton was scuttled by torpedoes from USS Reno (CL-96). Meanwhile, after being battered by U.S. submarines and aircraft, a portion of the Japanese force appeared to be retiring to the west, but surprisingly changed course and headed straight towards Leyte.

In the early hours of Oct. 25, the Japanese force in Suriago Strait was essentially annihilated in a night battle with battleships and destroyers from Seventh Fleet and the Australian navy. As the crippled enemy force attempted to steam north through the narrow strait, PT boats and destroyers relentlessly torpedoed the Japanese vessels. Battleship Fuso and destroyers Asagumo, Michishio, and Yamagumo were sunk.

Despite their losses, the Japanese pressed forward. At the end of the strait, California (BB-44), Maryland (BB-46), Mississippi (BB-41), Pennsylvania (BB-38), Tennessee (BB-43), and West Virginia (BB-48) were lined up as a trap. With the exception of Mississippi, each of the battleships had been damaged during the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack and subsequently returned to service. As a portion of the enemy force approached, American battleships with Australian cruisers delivered full broadsides. Battleship Yamashiro was sunk and cruiser Mogami was seriously damaged. The remaining Japanese force, not wanting to fall into the same trap, reversed course and withdrew. The battle at Surigao Strait was one of the few naval battles in the Pacific in which aircraft did not play a significant role.

Meanwhile, another Japanese attack force, having passed through the San Bernardino Strait, steamed southward along the coast of Samar. Halsey, who mistakenly shifted Third Fleet to the north in pursuit of a Japanese decoy force, left the amphibious forces on Leyte essentially unprotected. With the bulk of Seventh Fleet engaged at Surigao Strait, all that stood between the landing beaches and the Japanese task force were the ships of Taffy 3. Although the Japanese had suffered significant losses throughout the battle, the task force approaching Taffy 3 was formidable. Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita’s force included his flagship Yamato, eight cruisers, and nearly a dozen destroyers. Taffy 3 had just six escort destroyers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. Besides being clearly outmatched, the three U.S. destroyers, led by USS Johnston (DD-557), launched aggressive torpedo attacks that damaged heavy cruiser Kumano and caused Yamato to take evasive maneuvers that temporarily took the ship out of the battle. Although Taffy 3’s aircraft were fitted more for close air support of landing forces, they dominated the airspace above the Japanese force. Taffy 2, which was a short distance away, eventually joined the fight. Three Japanese cruisers, Chikuma, Chōkai, and Suzuya, were sunk; a fourth, Kumano, was heavily damaged. Shortly afterwards, Kurita opted to retreat. In what would become one of the most unlikely victories of the Pacific War, Taffy 3 lost two destroyers, Johnston and Hoel, and destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts. In addition, escort carrier Gambier Bay was sunk by naval gunfire, and escort carrier St. Lo was struck and sank by a kamikaze attack. All of the crewmembers of Taffy 3 were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for the Battle off Samar. Johnston’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

In all, the Japanese attempt to repel the Allied landings on Leyte failed. Japan’s total losses during the Battle of Leyte Gulf amounted to three battleships, one large carrier, three light carriers, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and 11 destroyers. For the Americans, despite tough battles ahead, the offensive in the Philippines and beyond would relentlessly continue. Most important, the conquest of Leyte completely destroyed the strategic threat posed by the Imperial Japanese Navy. For more on the Battle of Leyte Gulf, read "Calmness, Courage, and Efficiency," by Historian Martin R. Waldman, which was recently published to NHHC's website.

The Heroism of James E. Williams

During the Vietnam War, Boatswains Mate First Class James E. Williams was assigned to the River Patrol Force whose mission was to intercept enemy arms shipments on the waterways of South Vietnam. On Oct. 31, 1966, Williams, who was patrol commander for his boat River Patrol Boat (PBR) 105 and another PBR were searching for Viet Cong operating in an isolated area of the Mekong Delta. Suddenly, guerrillas in two high-speed sampans opened fire. Williams and his crew neutralized one boat crew, but the other escaped in a nearby canal. As they gave chase, the PBR Sailors soon found themselves in a beehive of enemy activity. Viet Cong guerrillas fired rocket propelled grenades and small arms from fortified riverbank emplacements.

Against seemingly overwhelming odds, Williams led his PBRs against enemy junks and sampans while calling in naval aviation support. When UH-1B Huey helicopters from the Navy’s Helicopter Attack (Light) Squadron 3 arrived, he assisted in another attack that evening, turning on his boats’ searchlights so that the aircraft could easily identify and attack enemy forces, even though it exposed him to fire. After the battle was complete, the American naval force killed numerous Viet Cong guerrillas, destroyed more than 50 vessels, and disrupted a major Viet Cong logistical operation.

On May 14, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Williams with the Medal of Honor for “his extraordinary heroism and exemplary fighting spirit in the face of grave risks [that] inspired the efforts of his men to defeat a larger enemy force, and are in keeping with the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Williams received the following awards during a 20-year career that also included combat service during the Korean War: the Navy Cross, Silver Star (with one gold award star), the Legion of Merit (with Valor), the Navy and Marine Corps Medal (with gold star), Bronze Star (with two gold stars), Vietnam Cross of Gallantry (with gold star and palm), Navy Commendation Medal, Navy and Marine Corps Presidential Unit Citation (with one service star), Purple Heart (with two gold stars), Vietnam Service Medal (with bronze service star), Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, National Defense Service Medal (with bronze service star), United Nations Service Medal, Korean Service Medal (with two bronze service stars), Korean Presidential Unit Citation, Korean War Service Medal, and the Navy Good Conduct Medal (with four bronze service stars). Williams is considered the most decorated Sailor in U.S. Navy history.

After he retired from the Navy in 1967, Williams returned to his home state of South Carolina where he found another way to serve his country. In 1969, he was appointed U.S. Marshal for the District of South Carolina. In May 1977, he transferred to the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Georgia, where served as an instructor. He was called back to South Carolina in July 1979 under court appointment as U.S. Marshal for South Carolina and served in that position until April 1980. He was then transferred to U.S. Marshals Service Headquarters in Washington, DC, where he served until his retirement from federal service.

Williams passed away on Oct. 13, 1999, ironically the Navy’s birthday. He is buried at the Florence National Cemetery in South Carolina. USS James E. Williams (DDG-95) is named in his honor.

Beirut Attacks

In the early morning of Oct. 23, 1983, two truck bombs struck separate buildings housing U.S. Marines and French forces at Lebanon’s Beirut Airport, killing nearly 300 American and French servicemembers. The first suicide truck carried an explosive force of more than 12,000 pounds of TNT. The truck rammed through the gate at the entrance of 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, where the driver detonated the improvised bomb, killing 220 U.S. Marines, 18 Sailors, and three Army Soldiers. More than 100 were also injured in the attack. Minutes later, another suicide bomber struck the Drakkar building just a few kilometers away that killed more than 50 French troops. It was the single deadliest day in U.S. Marine Corps history since World War II’s Iwo Jima battles, and the single worst French military loss since the Algerian War (1954–1962).

In the aftermath of the attacks, all available French and American military personnel along with the Red Cross rushed in to help despite sporadic sniper fire. After dark, an Air Force C-9 medical evacuation aircraft landed at the airport and flew off with the first batch of wounded Marines. A Royal Air Force C-130 transport also arrived that evening, and the next day it left for Cyprus with a group of 20 severely injured Marines. Despite continued sniper fire, Air Force C-9s and C-141s also landed at the airport, loaded more wounded, and flew to hospitals in Cyprus, Naples, and Germany.

On Nov. 7, Marine Brig. Gen. Jim R. Joy arrived in Beirut to take command of all Marine operations in Lebanon. The next day, the Marines who had been protecting the Lebanese Science University were pulled back to the airport. Beginning on Nov. 17, Joy ordered the construction of additional bunkers and improvements on existing defensive positions that would help prevent another suicide bombing. Meanwhile, USS New Jersey (BB-62) had been on station in the waters off Beirut since Sept. 25, but had not fired the ship’s 16-inch or 5-inch guns. However, if the tenuous cease-fire broke down and the Marines ashore were again targets of rockets, mortars, and artillery, the battleship’s crew was prepared for action. Unfortunately, simply lobbing 16-inch shells into Lebanon would not be much help to the Marines, and a bombardment not carefully directed by spotters on the ground or in the air might kill and injure a number of civilians. On Dec. 4, however, artillery firing from an area dominated by Syrian forces killed eight Marines at the airport and injured two others. It was clear that there was no longer a supposed cease-fire, and President Ronald Reagan authorized retaliatory attacks.

That day, a strike force of 28 aircraft launched from USS Eisenhower (CVN-69) and USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) into the Bekaa Valley. During the engagement, two A-6 attack planes were shot down from intense ground fire. Lt. Mark Lange, pilot, was killed and Lt. Robert Goodman, bombardier-navigator, was taken prisoner. After the attack was complete, photos revealed the strike was a success. In the days following, reconnaissance flights were conducted without incident.

In the first two months of 1984, the situation in the country had severely deteriorated. The Lebanese army was plagued by defections and desertions, and consistent heavy fighting had further reduced its capabilities. By Feb. 7, Beirut had been lost to Muslim and non-Muslim militia. At this point, the Marine presence could no longer contribute to the hoped-for national reconciliation; so on that day, President Reagan ordered the Marines to withdrawal to Sixth Fleet ships offshore. By Feb. 23, the Marines began movement to rejoin their supporting ships, ending 17 months of continuous operations in the country.