The History of the Navy Nurse Corps

Established 13 May 1908

Nearly 50 years before the creation of the Navy Nurse Corps, women were providing nursing care for military casualties.

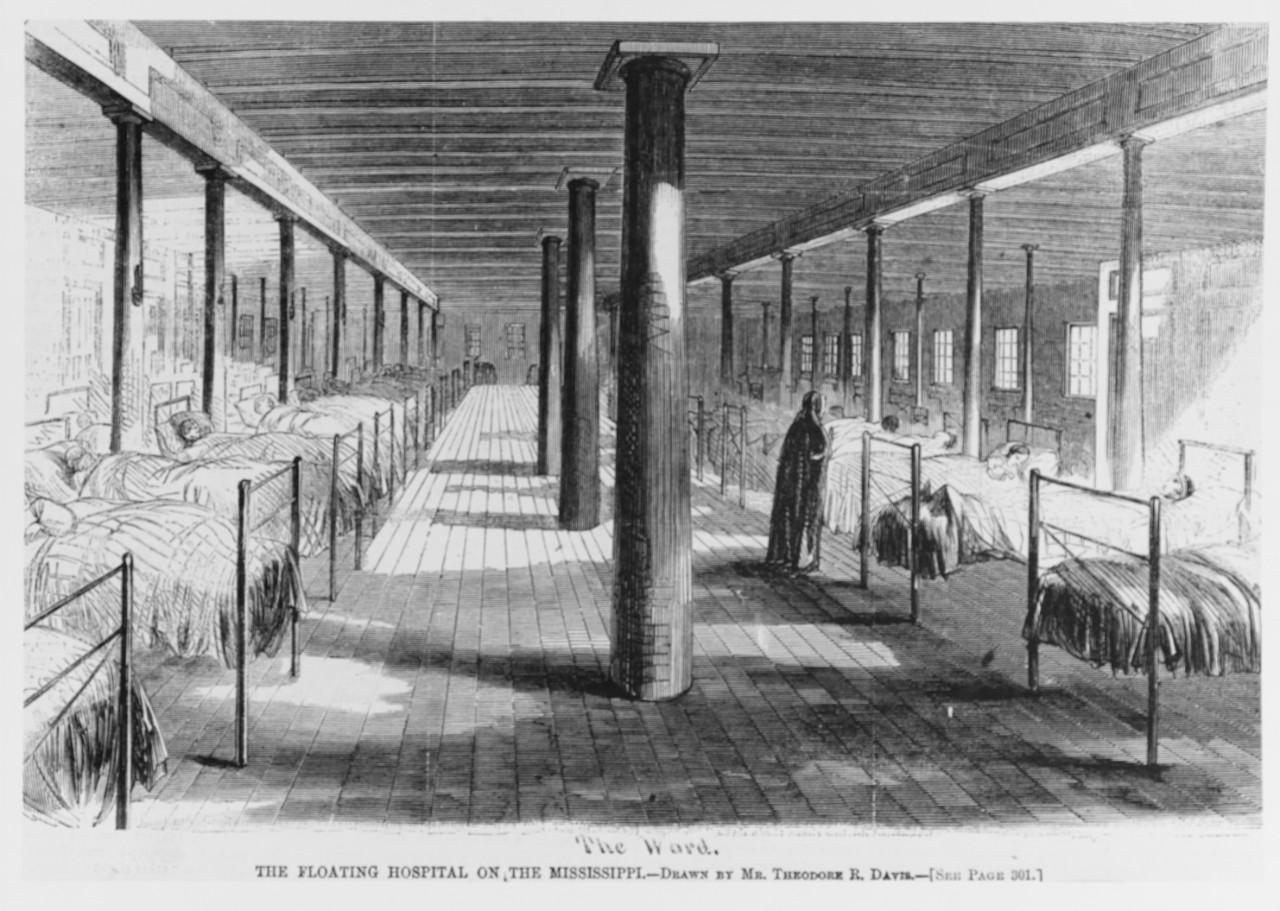

The need for nursing help during the Civil War led the Navy to bring volunteer nurses aboard its first hospital ship Red Rover in 1862. Four Catholic nuns from the Sisters of the Holy Cross joined the medical personnel aboard Red Rover when it sailed on 29 December 1862.1 Throughout the Civil War, Red Rover operated along the Mississippi River, ferrying military patients (both Union and Confederate) to shore hospitals.2 Two of the nuns remained on board until Red Rover was decommissioned 17 November 1865.

Additionally, several Black women, listed as “contraband of war” on Red Rover’s deck log, performed nursing duties aboard the hospital ship.3 Ann Stokes, a Black woman, boarded Red Rover in January 1863 and served aboard the ship until October 1864.4 She served as a nurse and later received a pension for her 18 months of service in the Navy.5

During the Spanish–American War, the Navy employed volunteer nurses to supplement the hospital corpsmen and male Navy doctors. The volunteer nurses were often recent medical school graduates or were on registries of non-profit organizations such as the American National Red Cross or Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).6 The Navy could not promise they would be paid, although they were told they would be reimbursed for traveling expenses and receive moderate pay, if the means were available. They ultimately received $30 a month, plus ration allowances. The money came from private funds, not Congress.7

On May 13, 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Naval Appropriations Bill that authorized the establishment of the Navy Nurse Corps. The first nurses inducted into the corps were dubbed “the Sacred Twenty.” Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee and Esther Voorhees Hasson—who worked as an Army contract nurse aboard Relief during the Spanish–American War—were two members of this first group of Navy nurses. Both went on to become superintendents of the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps.

The standards for Navy nurses were high. Applicants had to be graduates of a general hospital training school with at least a two-year program and clinical experience in “medical, surgical, care of men, and contagious diseases.”8 All training and experience must have been acquired in a hospital.

The new nurses completed at least three months of orientation and training in naval medicine at the naval hospital in Washington, DC, before being assigned to naval hospitals in Mare Island, California; Washington, DC; Norfolk, Virginia; Annapolis, Maryland; and Brooklyn, New York.9

By 1910, nurses began filling billets at hospitals outside the continental United States. The first overseas station staffed with Navy nurses was Naval Hospital Cañacao, located at Cavite Navy Yard, in the Philippines.

Responsibilities of chief nurses included overseeing living quarters, keeping a daily log of nurses’ services provided, submitting quarterly performance reports, and training hospital corpsmen in nursing skills.10 In addition, they needed to maintain discipline amongst the nurses and ensure that there was no fraternization between enlisted corpsmen or patients.11

In 1910, to entice more women to serve in the Nurse Corps, the Navy increased starting pay from 40 dollars a month to 50, with an additional 10 dollars a month for service in hospital ships, or overseas. However, unlike other military personnel, nurses did not receive a uniform or housing allowance.

In 1908, U.S. Navy hospital ships included Relief and Solace, neither of which had a complement of female nurses. Solace already had 50 male hospital corpsmen aboard and Relief became a stationary floating hospital and dispensary in Olongapo, Philippines, after being severely damaged in a typhoon. The Navy changed the damaged hospital ship’s name to Repose on 11 April 1918 so it could assign Relief to a new hospital ship being built at Philadelphia Navy Yard.

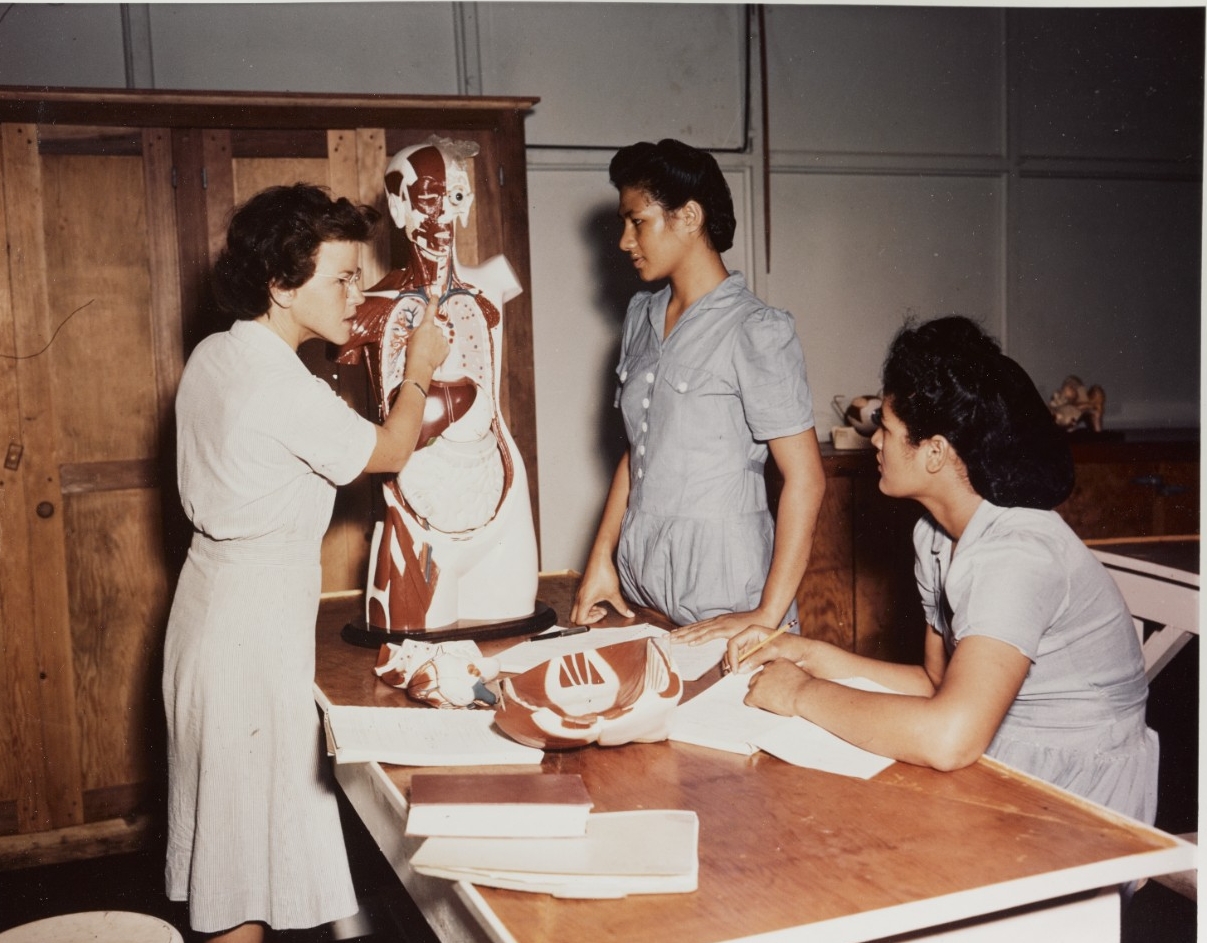

By the time the United States entered World War I, nurses were working at six overseas stations in the Pacific and Caribbean. Locations included the Philippines, Guam, Hawaii, Samoa, the Virgin Islands, and Cuba. Navy nurses worked in naval hospitals and established native nursing schools to help combat disease and improve quality of life for the local population. In 1911, the Navy sent a chief nurse, with two other nurses, to Guam to establish a nursing school. The nurses taught the local women midwifery as well as health, hygiene, and sanitation.12 The school was a success and the Navy decided to do the same thing in Samoa, on the naval station at Tutuila. The Navy sent two nurses there in 1916 to teach the local women nursing skills. Graduates of the program found positions in the naval hospital, which initially lacked trained staff. Navy nurses were also sent to the Virgin Islands to establish training schools and teach local women practical nursing and hygiene. Another school opened in Haiti in 1918, but closed in 1920, due to a personnel shortage in the Navy Nurse Corps. The nursing school on the Virgin Islands operated into the 1930s. The native hospital and school of nursing on Guam stayed open until July 1950.

On 2 December 1918, Navy nurses were assigned to transport duty for the first time on George Washington. The nurses were on board to tend to the wounded troops being transported home from war. These were the first nurses to be assigned to temporary transport duty.13

During this time, the 1918 influenza pandemic was in full force. Large numbers of influenza cases developed on board transport ships and naval hospitals admitted 91,656 patients from the end of August to the end of December 1918.14

One Army commander witnessed the efforts of the Navy nurses on board a transport ship full of sick troops during World War I:

“They worked night and day in the cold and damp, on decks that were being washed by seas, without any lights whatever, exposed to the dangers of contagion with a deadly malady, and they have rendered these services most cheerfully.”15

Nineteen Navy nurses died during World War I—over half of them from influenza.16 Three of the four Navy Crosses awarded to Navy nurses were given posthumously to women who died in the line of duty from influenza.

The nurses that received the Navy Cross posthumously were: Marie Louise Hidell, Lillian Mary Murphy, and Edna Elizabeth Place.17

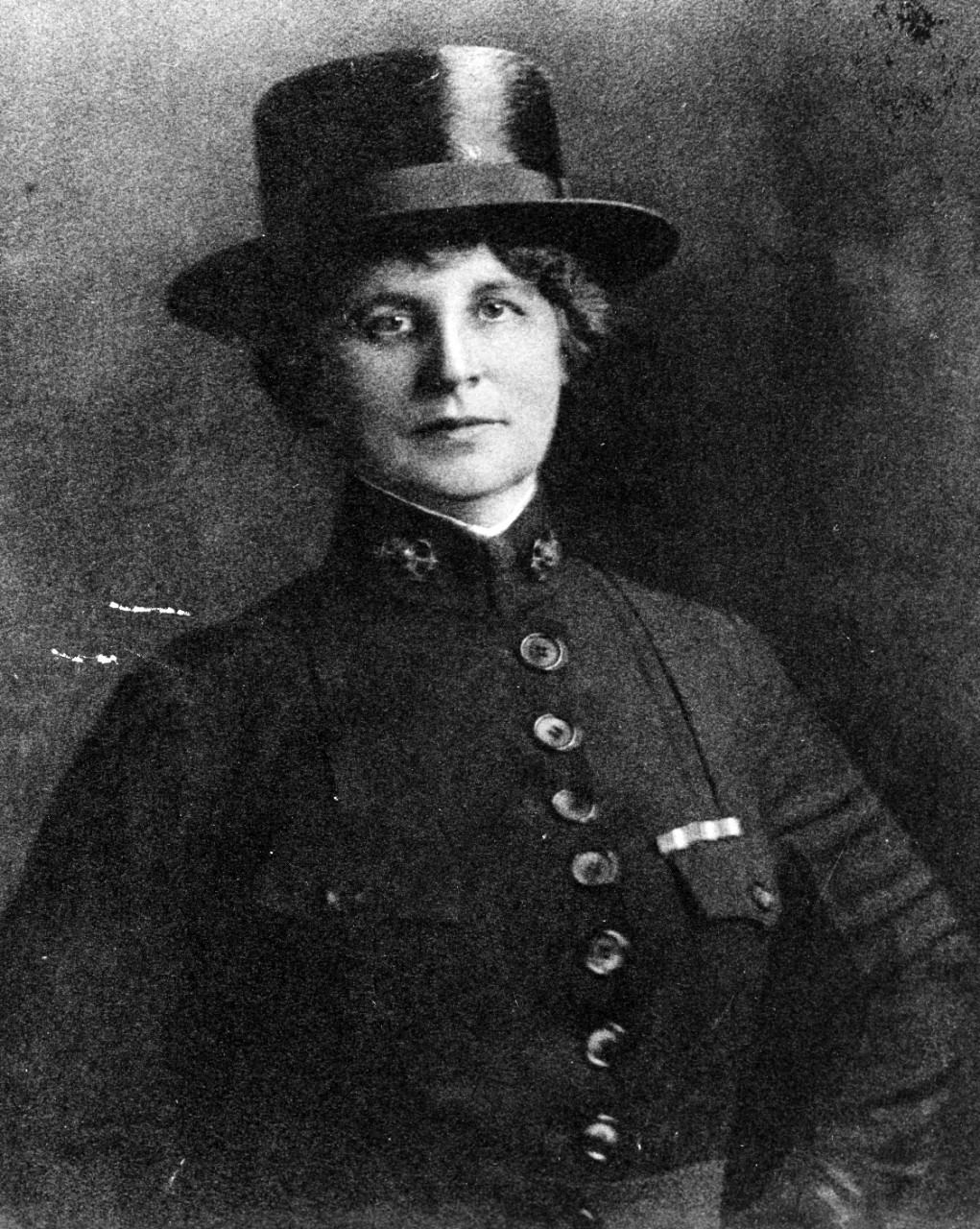

Superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee received a Navy Cross for her leadership of the Navy Nurse Corps during World War I. She was the first living woman to receive a Navy Cross.

When the United States entered World War I, there were 466 total active, U.S. Naval Reserve and U.S. Naval Reserve Force nurses in the Navy Nurse Corps. To meet wartime obligations, recruitment and pay of these nurses increased. By 1918, 1,386 nurses (active and Reserve) filled the ranks. In July of that same year, base pay increased to 60 dollars a month.

In June 1920, with the passing of the Army Reorganization Act, Congress authorized “relative rank” to Army nurses, but not to Navy nurses. Although relative rank was less than permanent rank and did not give the Army nurses the same base pay commissioned officers received, the act gave Army nurses the opportunity to wear rank insignia and hold the authority of officer rank.18

In August 1920, Navy nurses reported aboard Relief (AH-1)—the first group of female Navy nurses to be permanently assigned to a hospital ship.19 Chief Nurse Josephine Beatrice Bowman, one of the Sacred Twenty, accompanied 10 other nurses aboard Relief on its first voyage. On board, the nurses had the responsibility of directing the activities of the 184 hospital corpsmen assigned to the ship as well as providing nursing and medical care to the Atlantic Fleet.20

Beginning in October 1922, nurses were offered Navy-sponsored advanced training in dietetics, laboratory techniques, anesthesia, physiotherapy, tuberculosis nursing, and instruction of student nurses.21 This advanced training helped them stay current and put them on equal footing with civilian nurses. These professional education opportunities were something that Superintendent Higbee had helped secure through her legislative efforts.22 One month later, on 30 November 1922, Higbee requested to be honorably discharged. J. Beatrice Bowman was appointed as superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps after Higbee resigned.

During her tenure, 1922–1935, Bowman continued Higbee’s efforts to attract more nurses and improve benefits for those already serving. In 1923, nurses began receiving government-issued uniforms for the first time. Prior to 1923, nurses had to provide their own. In 1930, active duty members of the Nurse Corps began to receive retirement pay.

In February 1942, upon the urging of Surgeon General Rear Admiral Ross McIntire, Secretary of the Navy William Franklin “Frank” Knox wrote Congress to request relative rank for the Navy Nurse Corps. Knox stated that not giving Navy Nurse Corps personnel rank was “unsatisfactory and confusing,” and that it was needed to “increase the professional efficiency of the Corps.”23 Congress agreed, and on 3 July 1942, Navy nurses attained relative rank. The bill prescribed the following: the superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps would be a lieutenant commander; assistant superintendent would be a lieutenant; chief nurses would hold the rank of lieutenant (j.g.); and all other nurses would be ensigns. The new legislation also detailed that they would have authority “next after commissioned officers of the medical and dental corps in and about naval hospitals and other medical activities.”24

Congress passed legislation authorizing temporary rank and pay increases in December 1942. Ensign pay increased from 90 dollars a month to 150. Additionally, Navy Nurse Corps superintendents were now eligible for the rank of captain. On 22 December 1942, Superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps Sue Dauser was sworn in as captain. She was the first woman in the Navy to wear a captain’s four gold stripes.25

Captain Sue S. Dauser (Retired) receives the Distinguished Service Medal from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 1 December 1945. The medal was awarded for exceptionally meritorious service as superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps during the pre-war period and during World War II. Captain Dauser's retirement was announced on 9 November 1945 (NHHC, NH 97170).

On 26 February 1944, Congress passed Public Law 238 which authorized temporary commissioned rank for members of the Navy Nurse Corps for the war and six months afterward.26 They would now receive the same rank, pay, and privileges as all other commissioned naval officers—albeit temporarily. In comparison, women who joined the Navy as officers in the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) (created in July 1942) had been receiving the same rank and pay as their male counterparts for years.27

Attaining equal pay was something several superintendents pushed for, including former chief nurse and superintendent, Lenah Higbee. The Navy honored Higbee (who died 10 January 1941) by commissioning Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee (DD-806), in her honor. The destroyer was the first Navy warship to be named after a woman. A second Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee (DDG-123) was christened 25 April 2021. It is scheduled to be commissioned in 2024.

During World War II, more than 11,000 women served in the Navy Nurse Corps (including active duty and Reserve). Navy nurses were on 12 hospital ships, 40 naval hospitals, 176 dispensaries, and medical evacuation planes. They served both at naval activities in the United States as well as overseas to include: New Zealand, Australia, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Russell Islands, Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Marianas Islands, Virgin Islands, England, Africa, Italy, Newfoundland, Bermuda, Cuba, and Trinidad.28

U.S. Navy nurse Lieutenant (j.g.) Asplan stands by released prisoner of war Alfred Sorenson, U.S. Army, as he contemplates a full meal on board hospital ship Benevolence (AH-13), 30 August 1945. Sorenson was captured at Corregidor on 6 May 1942. He was rescued from a POW camp in the Tokyo area (NHHC, 80-G-490452).

In January 1942, eleven nurses attached to Cañacao Naval Hospital at Sangley Point, Cavite, Philippines, were captured as prisoners of war (POWs) when the Japanese invaded the Philippines in January 1942. After the Japanese raided the Cavite Navy Yard on 10 December 1941, the nurses evacuated with their patients to Sternberg Army Hospital in Manila, Philippines. After the hospital became overcrowded, they set up a makeshift hospital at another location in the area with the assistance of Army medical teams.29 When the American troops left Manila in late December 1941, the Japanese took over the city. The Japanese classified the Navy nurses as civilians (due to their gender) and sent them to a prison camp for enemy nationals on Santo Tomás University, in Manila.30 Eventually, the Japanese transferred them to Los Baños Internment Camp, located 25 miles southeast of Manila, where the Navy nurses set up a 25-bed hospital. The nurses continued to provide care for the camp prisoners until their release. The weary and malnourished group of nurses were finally rescued in February 1945, a month after American forces invaded the Philippines.

U.S. Navy Nurses, held as Japanese prisoners of war since 1942, talk with Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid after their release from a Luzon internment camp, March 1945. Photographed on Leyte. Left to right: Dorothy Still, Maureen Davis (RN), Eldene Paige, Helen Grant (British RN), Basilia Torre Stewart (RN), Helen Gorzelanski, Mary Rose Harrington, Margaret Nash, Goldie O'Haver, Mary Chapman, Laura M. Cobb, Susie Pitcher, Bertha Evans and Admiral Kinkaid (NHHC, NH 95053).

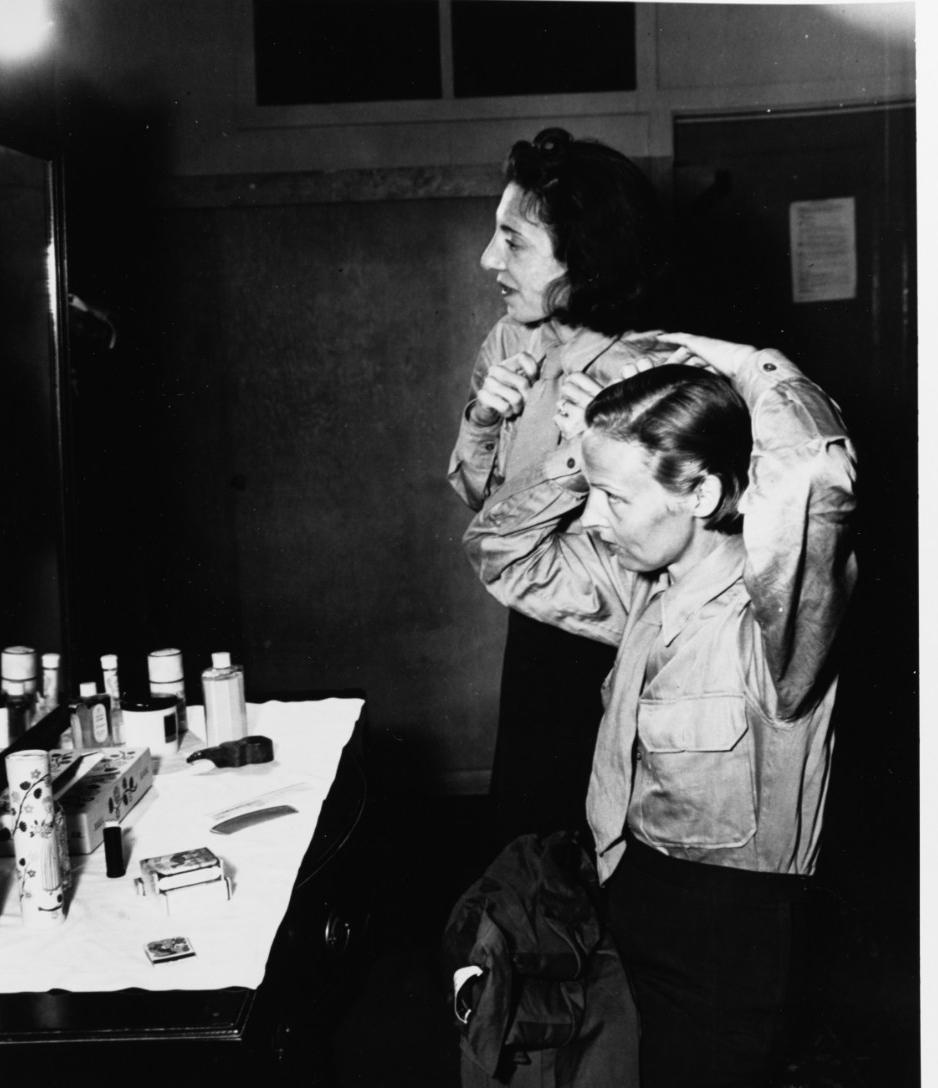

Navy nurses Dorothy Still and Helen Gorzelanski enjoy a little bit of luxury while en route home after being freed from the POW camp at Santo Tomas, Philippines, early March 1945. Dressed in Army nurse uniforms as they were the only ones available, they are shown in the nurses quarters at the naval hospital, in Aiea, Honolulu (NHHC, NH 94949).

In March 1945, the first Black nurse, Phyllis Mae Daley, received a commission in the U.S. Naval Reserve. Daley was a graduate of Lincoln School of Nursing in New York and student of public health at Teachers College, Columbia University. In the next two months, three more nurses followed: Edith Mazie Devoe, of Washington, DC; Helen Fredericka Turner, of Augusta, Georgia; and Eula Loucille Stimley, of Centreville, Mississippi.31

Navy Commander Thomas A. Gaylord (Retired) administers oath to five new Navy nurses commissioned in New York on 8 March 1945. Phyllis Mae Daley is the second from the right (NARA, 520618).

During World War II, the Navy began instituting programs for flight nursing. In 1943, the first two Navy nurses received air evacuation training. A year later, the Navy opened the School of Air Evacuation Casualties at Naval Air Station (NAS) Alameda in December 1944. By March 1945, 84 women had become Navy flight nurses.32

On 6 March 1945, 22-year-old Navy flight nurse, Ensign Jane Kendeigh became the first Navy nurse to arrive on an active Pacific battlefield.33 From 6 March to 21 March 1945, Kendeigh and other Navy flight nurses medevacked 2,393 American military personnel from Iwo Jima.

Navy flight nurses walk away from a Naval Air Transport Service Douglas R5D Skymaster evacuation transport aircraft on a Pacific Airfield, circa spring 1945. Left to right: Lt. j.g. Lydia Masserine, Lt. Stella Makar, Lt. j.g. Dorothy Wood, Lt. Hope Toone, Lt. j.g. Mae Hanson, and Ensign Winifred Jennings (NARA, 80-G-K-5446)

On 16 April 1947, the Army-Navy Nurses Act established the Navy Nurse Corps as a permanent staff corps in the Navy’s medical department and authorized officer rank for Navy nurses. It granted both Army and Navy nurses permanent commissioned officer status. Nurse ranks ranged from ensign to commander, with the director of the Navy Nurse Corps filling a captain slot.34

After the war, demobilization reduced the number of nurses in the Corps. In May 1946, there were 7,500 Navy nurses.35 By 1948, there are only 1,976.

On 30 June 1950, five days after the start of the Korean War, the Navy instituted an involuntary recall of Navy Reserve nurses. Some recalled nurses were sent to duty stations in the United States while others received orders to go overseas to the Far East Command.

Navy nurse Lieutenant Sarah Josephine Griffin assists an injured Korean War veteran as he learns to use his two artificial legs, at the Rehabilitation Center, Naval Hospital, Oakland, California, 1951. Lieutenant Griffin, who had lost her lower left leg as a result of an accident, was recalled to active duty during the Korean War to work with other personnel who had suffered the loss of limbs (NHHC, NH 94946).

Due to the need for rapid deployment, their records were not checked for a change in marital status. Many of the nurses had gotten married since they left active duty following World War II. According to Navy regulations at the time, married nurses were disqualified from service. In several situations, the married nurses had already been deployed to their duty stations by the time any discrepancies were found. They then had to be sent home and replacements found.36

Throughout the war, nurses served on the Navy’s three hospital ships: Haven (AH-12), Consolation (AH-15), and Repose (AH-16), which operated in the Korean waters. The ships served as station hospitals—rotating in and out of Korean ports. Each could accommodate 800 patients and the medical staff included 25 medical officers, three dental officers, 200 hospital corpsmen and 30 nurses.37

On 25 August 1950, hospital ship Benevolence was conducting sea trials in the San Francisco Bay when it collided with a civilian freighter and sank. Benevolence was carrying 15 Navy nurses. Fourteen nurses survived, while one nurse, Lieutenant Wilma Ledbetter, died of shock and exposure after being rescued from the water.38

A month later, more nurses lost their life while on their way to treat Korean War casualties. Eleven Navy nurses died on 19 September 1950, when a military transport plane en route to Naval Hospital Yokosuka went down at Kwajalein, Marshall Islands.

In December 1950, Navy nurses and hospital other medical staff struggled to meet an ever-increasing patient load at Naval Hospital Yokosuka, one of the main U.S. military hospitals in the Far East. From 6 to 7 December 1950, during the battle of Chosin Reservoir, 2,022 patients were admitted to Naval Hospital Yokosuka.39 By the end of December 1950, 5,927 casualties were admitted.40 At the beginning of the war, there were eight nurses on staff at Naval Hospital Yokosuka. By the end of December 1950, there were 201.41

The Korean War forced the Navy to increase its number of nurses. After the war, the Navy’s Medical Department suffered cutbacks, and there was once again a shortage of nurses.

In 1954, the Navy began offering nursing education incentives to recruit candidates and enhance retention. In July 1955, the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery’s Nursing Division established the Navy Enlisted Nursing Education Program (NENEP). Under this program, the Navy paid for a select number of Hospital Corps WAVES to attend a four-year college professional nursing program. Upon completion of their college education, nurses were commissioned as ensigns in the Nurse Corps. In 1960, this program was made available to women in all enlisted rates, not just Hospital Corps WAVES.

To attract prospective nursing graduates, the Navy started a Navy Nurse Corps Candidate Program in 1957 which paid for tuition, fees, books, and room and board for students completing their undergraduate degree in nursing. Upon graduation, they were commissioned as ensigns in the Nurse Corps Reserves, with an obligation to serve two years on active duty.42

In 1958, 12 nurses became the first in the country to take a course in nuclear nursing. The course, which started 3 September 1958 at the Naval Medical School at the National Naval Medical Center campus in Bethesda, Maryland, included instruction on the principles of radioisotope therapy and care of mass casualties from an atomic disaster.43 Director of the Nurse Corps, Captain Ruth Houghton, stated in a welcoming speech to the class that graduates would likely work in clinical radioisotope laboratories, therapeutic radioisotope wards, as teachers or in research.44

In 1959, the Navy began funding master’s or doctoral degrees for nurses to pursue in their off-duty hours. Opportunities expanded for Navy nurses to specialize in nursing administration/education, scientific research, or anesthesia.

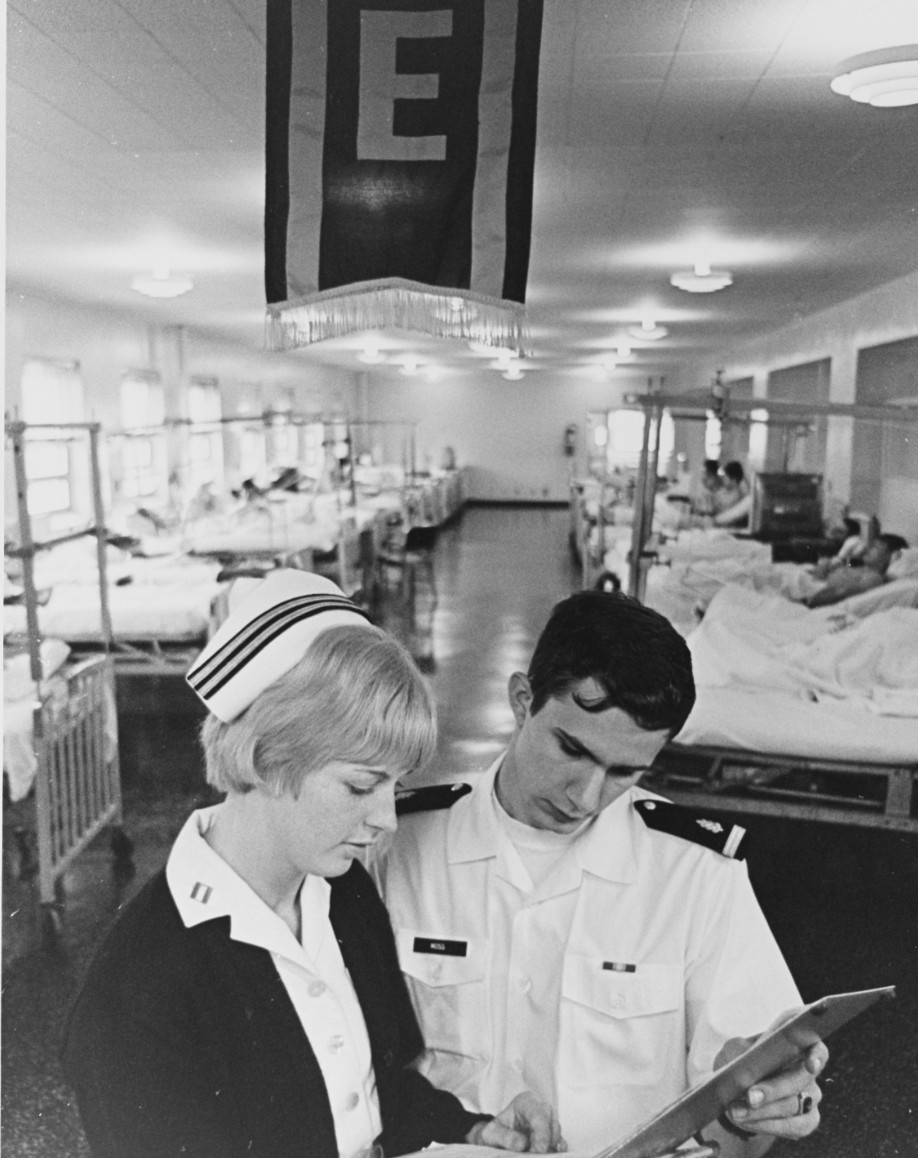

This same year, civilian and military personnel arrived in South Vietnam to provide advisory support to the anti-communist regime of Ngo Dinh Diem.45 Navy medical personnel followed shortly after to take over medical support of the Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) personnel from the American embassy in Saigon, Vietnam.46 The first group of Navy Nurse Corps officers arrived in early 1963 to begin working at Station Hospital Saigon. They were tasked with helping convert the former American dispensary into a 100-bed hospital. The hospital, which was under Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, provided medical service to military as well as embassy personnel and their dependents, Allied military personnel, and Vietnamese civilians.47 It was the Navy’s only hospital to receive combat casualties directly from the field.48 Twenty-three nurses worked at Station Hospital Saigon during its three years of operations. From the day it opened its doors in 1963 to the day it was transferred to the Army in 1966, more than 6,000 patients were hospitalized and 130,000 outpatients treated at the Saigon hospital.49

Station Hospital Saigon, once an apartment house, was the only U.S. Navy hospital in the world which treated combat casualties direct from the field (until Station Hospital Danang opened in the late 1960s). Station Hospital Saigon underwent a $100,000 expansion to improve its ability to care for U.S. personnel in the southern part of Vietnam (NARA, 1108879)

On Christmas Eve, 1964, the Viet Cong bombed a bachelor officer quarters (located in Brinks Hotel in Saigon). Four nurses, who lived in the officer quarters, were off duty when the attack occurred. Though the nurses were injured by exploding glass fragments, they refused treatment until all other injured were treated. They first assisted those in the building then returned to Navy Station Hospital, Saigon, to assist casualties in the emergency room and conduct triage.50 They became the first military women to be awarded the Purple Heart in the Vietnam War.51

Purple Heart awards are presented to staff nurses attached to U.S. Navy Headquarters Support Activity Hospital, Saigon, South Vietnam. Four nurses were injured in the bombing of the bachelor officer quarters based at the Brinks Hotel in Saigon on Christmas Eve, 1964. Among those to receive their awards during this ceremony were: left to right: Lt. Barbara Wooster, Lt. Ruth Mason, and Lt. j.g. Ann Reynolds (NHHC, NH-93962).

The nursing shortage continued to plague the Nurse Corps throughout the Vietnam War even as leadership expanded its education programs. The federal government lent a hand by creating the Nurse Training Act of 1964 to fund more nursing schools and student loans and scholarships.

In November 1964, Secretary of the Navy Paul H. Nitze revised Nurse Corps requirements to allow men to join the previously all-female Corps. This new policy also allowed qualified enlisted men of the Hospital Corps to apply for the Navy Enlisted Nursing Education Program (NENEP).52 From 1965 to 1968, five males joined the Nurse Corps as part of the Naval Reserve. In 1968, the first male officer joined the regular Nurse Corps. In total, 379 men served in the Nurse Corps from 1965 to 1971.53

That same year, the Navy Nurse Corps began granting waivers to permit female nurses to marry and have minor children in the home. Male nurses had always been allowed to marry and have dependents.54

In Vietnam, nurses also served on teams that provided medical support to South Vietnamese medical personnel as part of the Military Provincial Health Assistance Program. Through this program, Navy nurses worked alongside other military medical staff at various Vietnamese provincial hospitals, and were tasked with training the Vietnamese medical staff in surgical operations so they could help the local population. One Navy nurse, Bernadette McKay, who served at a hospital in Rach Gia, Vietnam (1965–66) described the challenges of the mission:

“Our mission was gigantic—to teach ourselves out of a job. We had to learn basic language and adapt to local customs. Progress was slow but steady and when we were relieved after one year, we proudly left four functioning OR technicians, two emergency room workers, functioning X-ray department, a blood bank program, a competent lab technician, and more importantly— a very capable surgeon.”55

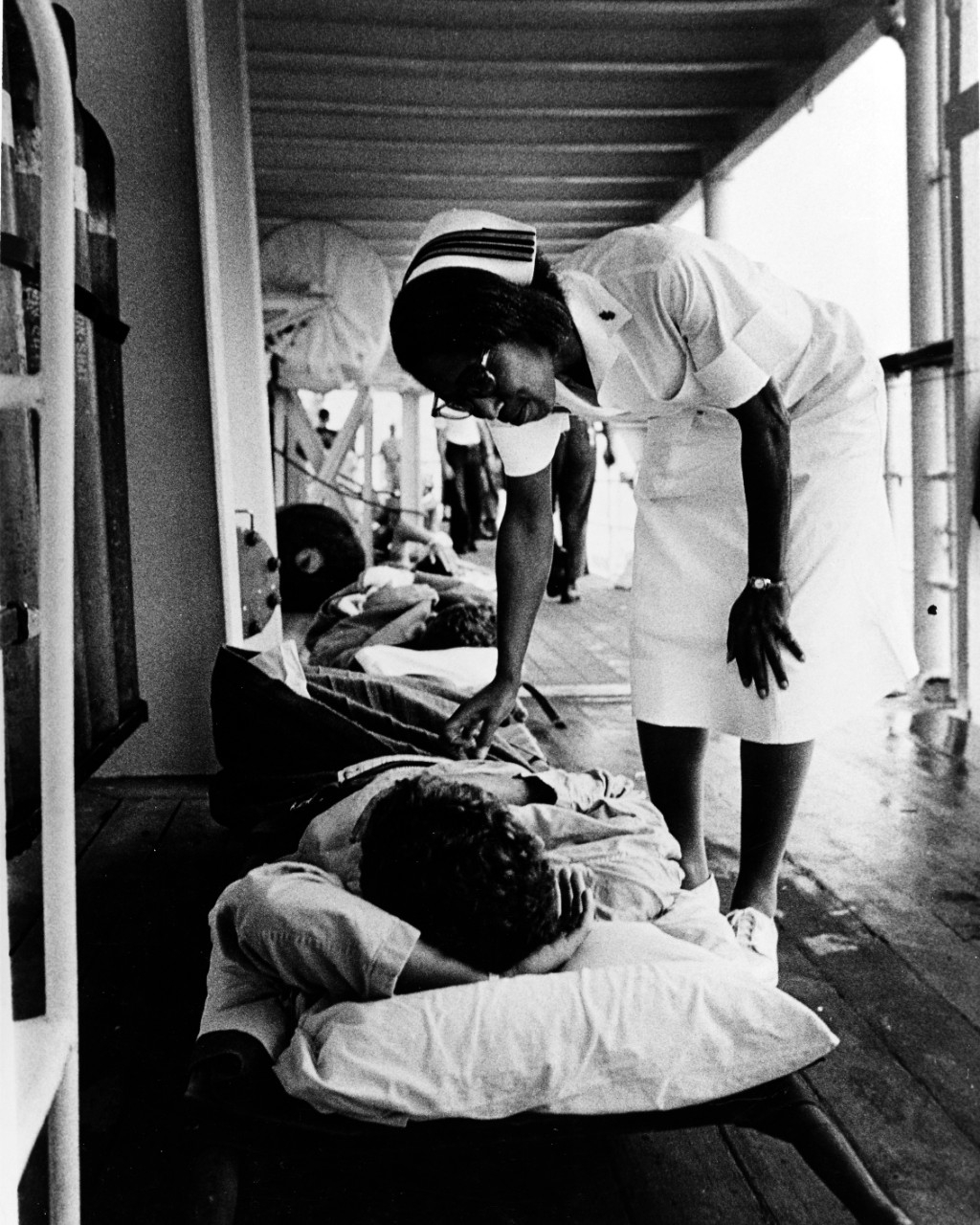

Nurses also served on hospital ship Repose (AH-16) which operated as a 721-bed station hospital in the Danang, Chu Lai, Phu Bai, Dong Ha, and Quang Tri areas of Vietnam. In March 1966, 29 nurses served on hospital ship Repose (AH-16). During periods of intense fighting, it was not unusual for helicopters to deliver as many as 200 patients in a 24-hour period.56

On board Repose (AH-16), a Navy nurse offers a word of encouragement to a patient about to leave the ship for further treatment in the United States, October 1967. Repose was operating in the South China Sea, a few miles south of the 17th parallel, the provisional military demarcation line between North and South Vietnam (NHHC, USN 1142182).

Navy hospital ship Sanctuary (AH-17) took over when its sister ship Repose departed for the United States on 14 March 1970. Sanctuary also had a full complement of 29 nurses. It operated from April 1967 to November 1972, in the I Corps tactical area, the northernmost part of South Vietnam. Sanctuary rotated every two to four days between Danang, Chu Lai, Phu Bai, and Dong Ha, as needed by the Marines fighting ashore.

When the number of casualties flowing into Station Hospital Saigon became overwhelming for the 100-bed hospital, the Navy opened Station Hospital Danang at Naval Support Activity (NSA) Danang. The first Navy nurses reported to the Danang hospital in August 1967. Originally designated as a 600-bed hospital, it was increased to 700 beds two years later. It became the largest combat casualty treatment in the world. In addition to working long hours, nurses were also occasionally exposed to dangerous conditions. One operating room nurse recalled assisting in two operations where live shells were removed from patients’ bodies on the operating table.

By the time Station Hospital Danang was transferred to the Army three years later, a total of 63,000 patients had been through its doors.57

On 27 April 1972, the director of the Navy Nurse Corps and World War II veteran, Rear Admiral Alene B. Duerk, became the first woman in the Navy’s history to be promoted to flag rank.

After the war in Vietnam ended, nurses continued to fulfill peacetime roles, serving at naval hospitals at bases around the world and on hospital ships.

From 1990–1991, nurses served on hospital ships USNS Mercy (T-AH 19) and USNS Comfort (T-AH-20), both of which deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Desert Storm to provide care to U.S. military personnel and support multinational allied forces.58

In November 1993, Congress repealed section 6015 of Title 10, U.S. Code, which previously had prohibited women from serving on combatant ships and aircraft. As a result, nurses were eligible for duty on aircraft carriers and other combatant ships.

Beginning in the early 2000s, Navy nurses deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq for Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. From 2010–2020, more than 3,000 Navy nurses deployed in support of every combatant command’s area of operations worldwide.59 Since April 2020, Navy nurses have been deploying to hospitals across the country to support civilian healthcare personnel in the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

—Wendy Arevalo, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC Resources

Navy Nurses at Work Behind Enemy Lines in the Philippines by Adam Bisno, NHHC, COD.

Further Reading

Godson, Susan H. Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S. Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Sterner, Doris. In and Out of Harm's Way, A History of the Navy Nurse Corps. Seattle: Peanut Butter Publishing, 1997.

***

Notes

1 Susan H. Godson, Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S. Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 19.

3 Steven L. Roca, ”Presence and precedents: The USS Red Rover during the American Civil War, 1861–1865,” Civil War History 44, no. 2 (1998): 92, quoted in Kati Engel, “Their Navy: Women in the U.S. Navy at Sea, 1862–2022,” (paper presented at the Annual Conference of the North American Society for Oceanic History, Wilmington, NC, June 2022).

4 Roca, 110; Also see Lisa Y. King, “In Search of Women of African Descent Who Served in the Civil War Union Navy,” Journal of Negro History 83, no. 4 (Autumn 1998): 307.

5 “General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934,” RG 15, T 288 (microfilm), 544 rolls, roll 455; "Deck Log," vol. 1, RG 24, National Archives, Washington, DC, quoted in Engel.

7 Doris Sterner, In and Out of Harm’s Way, A History of the Navy Nurse Corps (Seattle, WA: Peanut Butter Publishing, 1997), 10.

13 Navy Department Library, Special Collections, “Information Chart of Chronological History Nurse Corps, U.S. Navy.”

15 Jane Delano, “The Red Cross,” American Journal of Nursing 19 (December 1918): 188, last accessed 23 August 2022, as quoted in Godson, 76.

16 John G.M. Sharp, Naval History and Heritage Command, The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard Naval Training Station Roads and the Norfolk Naval Hospital, last modified 2 Dec 2020.

18 U.S. Army Center of Military History, Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1995).

19 Navy Department Library, “Information Chart of Chronological History Nurse Corps.”

20 Christine Curto, “Nurse Pioneers and the Hospital Ship Relief,” Navy Medicine 83, no. 3 (1992):22.

22 Benjamin Drew, “Lenah Sutcliffe Higee: Navy Nurse Corps Pioneer,” Naval History Magazine, April 2017.

24 “News about Nursing,” The American Journal of Nursing 42, no. 8 (1942): 954–78, last accessed 16 August 2022, quoted in Godson, 143.

26 Hearings on H.R. 4411 to Address the Pay and Allowances of Members of the Navy Nurse Corps, and for Other Purposes Before the Committee of Naval Affairs, 79th Cong. 1663 (1945) (statement of Vice Adm. Ross T. McIntire, Surgeon General of the United States Navy accompanied by Capt. Sue S. Dauser, superintendent, Navy Nurse Corps), accessed 16 August 2022, Google Books; Godson, 143.

27 NHHC, How to Serve Your Country in the WAVES, 1943, last updated 16 October 2019.

28 Navy Department Library, “Information Chart of Chronological History Nurse Corps.

29 Dorothy Still Danner, “Reminiscences of a Nurse POW,” Navy Medicine 83, no. 3 (1992): 36–37.

30 Adam Bisno, “Navy Nurses at Work Behind Enemy Lines in the Philippines,” NHHC, last updated 10 March 2020.

31 André Sobocinski, “A Look Back at the First African-American Nurses in the Navy,” Navy Medicine, last updated 6 February 2021.

32 André Sobocinski, “Angels of the Airfields: Navy Nurses of Iwo Jima and Okinawa,” U.S. Navy, 2 May 2022.

33 Sobocinski, “Angels of the Airfields.”

36 Frances Omori, Quiet Heroes: Navy Nurses of the Korean War 1950–1953, Far East Command (Saint Paul, MN: Smith House Press, 2000), 12.

38 Linda Witt, Judith Bellafaire, Britta Granrud and Mary Jo Binker, “A Defense Weapon Known to be of Value”: Servicewomen of the Korean War Era (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2005), 218; Godson, 186.

43 “Notes,” Military Medicine 124, no. 3 (March 1959): 242; Godson 198.

45 Jan K. Herman, Navy Medicine in Vietnam: Passage to Freedom to the Fall of Saigon, (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2010), 5.

47 Bobbi Hovis, Station Hospital Saigon, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 17.

49 Maryanne Gallagher Ibach, “Memories of Navy Nursing: The Vietnam Era,” last accessed 25 August 2022, 1.

51 Ibach, “Memories of Navy Nursing,”1.

55 As quoted in Ibach, “Memories of Navy Nursing.”

56 Ibach, “Memories of Navy Nursing.”

57 Ibach, “Memories of Navy Nursing.”

58 "USNS Mercy History,U.S. Navy Military Sealift Command, accessed on 29 August 2022.

59 Kuehner, "The Navy Nurse Corps: Needed Now More than Ever, U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings, 148, no. 2 (February 2022), accessed on 30 August 2022.