Navy Nurses at Work Behind Enemy Lines in the Philippines

1941-1945

The 11 liberated Navy nurses with Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid on 23 February 1945. Left to right: Susie Pitcher, Dorothy Still, Basilia Stewart, Goldie O’Haver, Eldene Paige, Vice Admiral Kinkaid, Mary Chapman, Laura M. Cobb, Maureen Davis, Mary Nelson (née Harrington), Helen Gorzelanski, Bertha Evans, Margaret Nash, Helen Grant, and Edwina Todd (NH 94947).

“Protect the babies with all your life,” Lieutenant Commander Laura M. Cobb, a supervisory U.S. Navy nurse, said to Lieutenant Edwina Todd and Lieutenant Margaret A. Nash, also Navy nurses, as they crawled aboard a tractor.[1] All of them had been imprisoned at the Los Baños Internment Camp on Luzon, still behind enemy lines until today, 23 February 1945, with the U.S. Army and Allied guerrillas conducting a raid to free the camp’s 2,100 prisoners, including Cobb, Todd, Nash, and eight other Navy nurses.

They had languished at Los Baños since May 1943 and in Japanese custody since early 1942. Malnourished and diseased themselves, the nurses nonetheless managed a makeshift hospital inside Los Baños, where they treated other internees as best they could under impossible conditions. Now, upon rescue, the nurses had to help move several patients, two infants––only days old––and their mothers all the way to safety. The beach lay two miles away and, from there, a bay had to be crossed before the internees and their liberators would be standing on U.S.-controlled territory.

The trip to the beach passed with little incident. Not so on the beach itself. There, Japanese gunners opened fire on the nurses and patients as they disembarked the tractors. “Stray bullets were going in every direction,” Nash remembers of the moments she spent trying to make it from the smaller tractor that had brought her to the beach to the larger amtrac (amphibious tractor) that would take her to safety. “I covered the baby,” named Elizabeth, “with a great big hat,” Nash explains, “and lay down on the sand over her.”[2]

A Soldier crawled over and told Nash what to do next: “When they stop shooting, [and] with all the strength God gave you, grab the baby” and get to the waiting amtracs.[3]

This daring rescue and dangerous escape came after three years of captivity, during which the 11 Navy nurses captured in Manila in 1942 managed not only to survive but to treat the sick and the wounded in their increasingly weak and imperiled prison communities. In many ways, these Navy nurses’ experiences were unique, but in still other ways, they faced challenges and decisions that would have been familiar to the millions of women across the globe trying to survive in captivity or under occupation, caught up in the most terrible war in modern history.

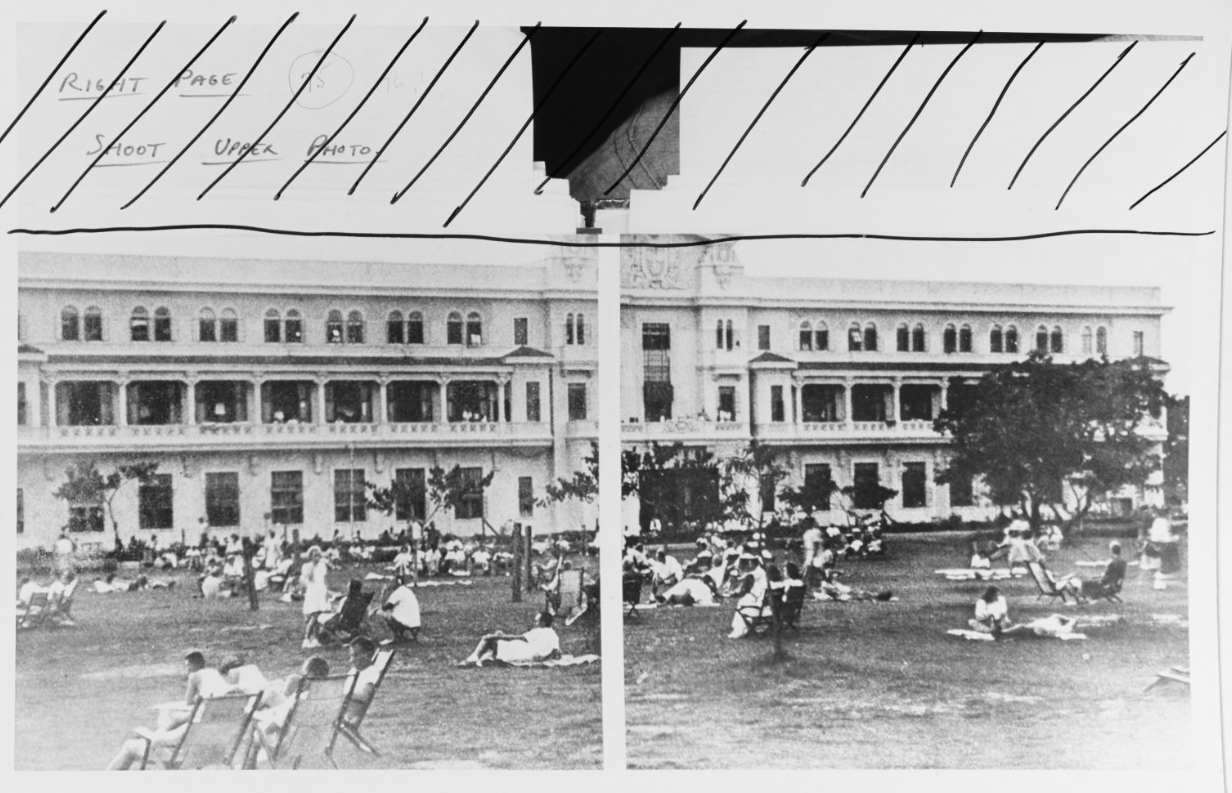

The Naval Hospital at Cañacao, Philippines, on the Eve of War—September–December 1941

The 11 Navy nurses captured by the Japanese in January 1942 had been working at the naval hospital at Cañacao when the war arrived there on 8 December 1941. On the edge of a peninsula, the hospital was colocated with Sangley Point Air Field and the Cavite Navy Yard, both of which became Japanese targets. The hospital itself occupied several white buildings surrounded by mahogany trees—a beautiful location before it was destroyed by aerial bombardment.[4]

Lieutenant Nash, the nurse who a few years later found herself spiriting the three-day-old baby Elizabeth to safety aboard a U.S. Army amtrac, had joined the Navy as a nurse in the 1930s. It was her uncle, a Congressman from Pennsylvania, who first suggested she join. She agreed, Navy service being a good opportunity for career nurses in the 1930s, when jobs were particularly scarce.[5] Her uncle’s advice made sense in the context of the Great Depression. What he could not know was that a career in Navy Nurse Corps would take Margaret straight into the swiftest defeat in U.S. military history: the fall of the Philippines in late 1941 and early 1942.

A few years later, in September 1941, Margaret Nash was working on Guam when she received transfer orders to the Philippines—“with only two hours’ notice to pack,” she recalls.[6] The haste was characteristic of this particular time and place, where U.S. Navy personnel were rushing to meet President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s goals for readiness to fight Japan. War had felt imminent since July of that year, when Roosevelt had made the decision to freeze Japan’s assets held in the United States, an escalation of tensions with the Empire of Japan, now in the process of conquering its neighbors and asserting mastery over parts of the Pacific, which Roosevelt understood as a threat to American interests and security.[7] Just after the asset freeze in August 1941, Roosevelt instructed General Douglas MacArthur, then the commander of U.S. Army forces in the Philippines, to bolster his defenses. (The Philippines were at the time an imperial possession of the United States.) Such bolstering depended in large part on the Navy which, between August and early December 1941, transported materiel and personnel—including Nash and other Navy nurses—to stations in the Philippines. The islands, by December 1941, boasted the largest concentration of U.S. airpower in all of the Pacific.[8] Ultimately, it was all for naught. The U.S. defense of the Philippines failed miserably, and that failure sealed Nash’s fate and the fates of her colleagues.

Leading up to the outbreak of war, Nash and the other nurses did their part to prepare. Amid frequent practice blackouts and other drills, the Navy nurses readied their hospital at Cañacao for war. They made and sterilized hundreds of dressings in anticipation of emergency surgeries and stocked up on supplies such as blankets, plasma, saline solution, and suture materials.[9] Supplies continued to pour in up to the last minute, in early December, when the Navy docked a massive convoy laden with 48 75-millimeter guns, millions of rounds of ammunition, 600 tons of bombs, and 70 aircraft.[10] It would all go up in flames a few days later.

Attack, Defeat, and Capture––8 December 1941 to 12 March 1942

General MacArthur learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor shortly after 3:00 a.m. in the Philippines, where it was already a new calendar day, 8 December. Even with orders from Washington, which were soon forthcoming, he failed to act for several hours. When he finally issued the orders for U.S. aircraft to take to the skies, it was far too late.[11]

The Japanese attacked from the air before U.S. planes could get off the ground. The attack was devastating, wiping out the Navy and Army’s ability to save the Philippines from Japanese conquest.[12] Nash and the other Navy nurses at Cañacao could not have known the extent of the damage at first. They were too busy trying to manage the emergency on the ground.

As bombs rained down on nearby U.S. Army and Navy installations, the Navy hospital at Cañacao overflowed with wounded Sailors, Soldiers, and administrative personnel. Just hours after the first aerial bombardment, the hospital ran out of beds, cots, and then floor space. The wounded had to be placed on the lawns, out in the open, even as the attacks continued.[13] As the raids seemed to be nearing the hospital, the Navy nurses, orderlies, doctors, and volunteers carried as many patients as they could from the lawns and wards to the basements. Later on 9 December, not yet 36 hours into the war, the Navy hospital staff moved the patients again—this time all the way to Sternberg Army Hospital in Manila proper.[14] Back at Cañacao, now empty, Japanese bombs soon destroyed the Navy hospital buildings and the rest of the structures on the peninsula.[15]

The Army hospital in Manila proved no safer. Military and civilian preparations for the siege of the city were quickly proving no match for the onslaught.[16] Nevertheless, Navy and Army nurses continued to manage the catastrophe by forgoing sleep and meals to maximize the time they could spend administering treatment to the wounded and dying. For nearly two weeks, they toiled in this nightmare scenario: an abject defeat.

Defeat seemed to be turning to rout when, at the end of December, MacArthur ceded Manila, the Philippines’ principal city, to the Japanese invaders. In advance of their arrival, MacArthur issued orders for the Army to pull out and moved his headquarters to the relative, if temporary, safety of Corregidor. On 26 December, American troops abandoned Manila, and the city—now in a power vacuum and burning—fell into anarchy and then chaos.[17]

Nevertheless, the 11 Navy nurses and other medical personnel kept working, now at a makeshift Army hospital at what had been Santa Scholastica College. In fact, the nurses, doctors, corpsmen, and orderlies never received orders to evacuate—they too, and their patients, had been abandoned in MacArthur’s flight.

“We were still in Manila waiting for orders when the Japanese took over in January,” recalls Lieutenant Dorothy Still, one of the 11 Navy nurses now trapped in a violent limbo.[18] Lieutenant Mary H. Nelson, also one of the 11, remembers the exact moment she knew she was under enemy jurisdiction: “When the Japanese army entered Manila, I went up to the third-floor tower at Santa Scholastica to watch their ‘triumphal march’ down the street. Leading the troops was a general riding in an open car, with flags and all. It was an eerie feeling.”[19] Nelson was likely staring at none other than General Masaharu Homma, Japanese commander-in-chief of the Philippines, who soon issued a succinct and unambiguous warning: “Offering resistance or committing hostile acts against the Japanese forces in any manner will lead the whole Philippines to ashes.”[20]

A few days later, still in the first week of January 1942, the Navy nurses and their colleagues received the first Japanese officers of the occupation. “They really didn’t believe we had patients,” according to Nelson, “and we had to take the dressings off [the patients] to show … the wounds.”[21] Mollified, the Japanese officers departed, but they left armed guards behind “to watch our every move,” as Nash recalls.

These armed guards represented the capture—the inaugural moment of the 11 Navy nurses’ captivity, a first step which led them deeper and deeper into isolation and misery as the war dragged on. Indignities and abuses piled one on top of the other, but gradually so, until 1945, when they would come out of a remote prison camp mere shadows of their former selves.

But for now, at this early stage of the occupation, the Japanese approach to civilian internees was more measured. On 3 January 1942, Although General Homma had indeed ordered all civilians in the Philippines to “sever their relations with the United States” and “obey” and “cooperate with” the Japanese army, he stopped well short of the annihilatory practices of the Japanese elsewhere and the Axis powers in general.[22]

The nurses and their colleagues were therefore able to keep working, if under guard, with little disturbance for almost two and a half months before the Japanese authorities finally broke up the hospital and transferred its staff and patients to various prison facilities. The nurses, classified by the Japanese as civilians because of their gender, went to the grounds of Santo Tomás University, Manila’s camp for enemy nationals.[23] As historians Mary Ellen Condon-Rall and Albert E. Cowdrey point out, “Allied and American nurses” tended to be “more fortunate than military captives”—at least at first—because Japanese policy and practice toward military personnel was uniformly brutal.[24] In fact, for the first half of the war between the United States and Japan, the prison systems for civilians and military personnel were completely separate, with the Imperial Japanese Army running the prisons for captured servicemen and the Japanese Department of External Affairs (the administration in charge of extracting resources, labor, and soldiers from occupied territories) running the prisons for enemy nationals.

On 12 March 1942, therefore, the 11 Navy nurses at Santa Scholastica were transferred to the campus of Santo Tomás, under the authority of the Department of External Affairs, whereas most of the patients, corpsmen, and doctors from Santa Scholastica were thrown into the notorious Bilibid prison.[25]

Santo Tomás Internment Camp for Foreign Nationals—March 1942 to May 1943

No sooner had the 11 Navy nurses arrived at Santo Tomás’s campus than an American civilian internee there, Dr. Charles Leach, approached them about working with him in the makeshift hospital that he and a group of interned nurses and other medical professionals had set up.[26] They and the 11 Navy nurses managed on their own there for four months, after which point several dozen Army nurses landed at the camp and took up posts at the hospital. The more nurses, the better, in a place like Santo Tomás, where diseases spread quickly. In one short period, in fact, nearly every child internee contracted either measles, whooping cough, or both.[27]

Santo Tomás housed nearly a thousand minors and just as many people over the age of 60—two especially vulnerable populations. Together, they made up half of the camp’s 3,800 internees (as of mid-1942). Adding to the age diversity was national diversity. Here was a polyglot cross section of Western expatriate society. Although the predominant language at Santo Tomás was English, the accents ranged from British to Australian to North American, and others got by on their native Dutch, Polish, Norwegian, and French.[28]

Like similar internment camps that had sprung up across the globe as a result of the world war, Santo Tomás had its own internee government composed mostly of men who acted as representatives of the prisoner population to the occupation authorities and who oversaw committees of internees established for the purpose of regulating labor, supplies, accommodation, behavior, and even entertainment on the site.[29] As historian Elizabeth M. Norman points out in her vivid history of the camp, however, Santo Tomás, “was still a prison, a place of the keepers and the kept,” despite “all its apparent amenities.”[30]

Food, for one thing, was in short supply and of limited variety and nutritional value. Grains were often spoiled—infested, even. With respect to nourishment, assistance from the local population of Manila became indispensable. For 1942 and much of 1943, vendors were allowed into Santo Tomás during the day to sell all manner of necessary goods and services to the internees.[31] As money dried up, however, the donations of Filipino friends and family outside the walls became vital.[32] Toward the end of the war, as conditions deteriorated, prisoners would have to go without the donations, too. The general food supply would eventually collapse under the strain of Japanese rapacity and the dislocating effects of the American reconquest of the Philippines. And even before this—the bloody end—and despite assistance from the outside, life was hard for the people of Santo Tomás.

As in camps elsewhere, the 11 Navy nurses and their thousands of fellow internees were forced to give up their civilian comforts and their privacy. They dressed and slept in cramped quarters on bejucos, woven or slatted cots ridden with bedbugs. Bathing became a special indignity. Groups of prisoners had to crowd under single shower heads and take turns stepping under the water. As one internee described this and other affronts, “You just … close your eyes and pretty soon you just kind of keep closing down and closing down because you can’t stand [it].[33]

A few months into 1943—a year into the Navy nurses’ stay at Santo Tomás—the camp’s population there reached 4,200. The overcrowding seemed palpable as the supply and administrative systems and practices in place started to break down in face of the ballooning population inside the camp and the worsening shortages of goods and services in occupied Manila more generally. The Japanese authorities therefore decided to move some of Santo Tomás’s prisoners out of Manila and into a new camp some 40 miles away, near a small town called Los Baños.[34]

It fell to the internee government to draw up a list of transfers. The task was easy, in fact, because the move to Los Baños, a new camp in the countryside, presented an attractive alternative to the crush of an already decrepit urban internment complex. For the Navy nurses, Los Baños became particularly appealing when Dr. Leach, their valued colleague, announced his decision to sign up for the transfer. Lieutenant Commander Laura Cobb, the chief nurse among the Navy nurses, agreed to accompany him with her staff of 10.[35]

On 14 May 1943, the 11 Navy nurses said goodbye to their Army colleagues and others at Santo Tomás, their home for these past 14 months, and boarded the trucks that would convey them to the cattle cars that would, in turn, take everyone down the 40 miles of track to Los Baños. The rail portion of the journey was slow going, and the lack of water and pressing heat proved almost unbearable. Nevertheless, all 11 Navy nurses and Dr. Leach made it to Los Baños well enough to get to work in short order.[36]

Los Baños Internment Camp—May 1943 to February 1945

The 11 Navy nurses found considerable work to do at Los Baños, a former agricultural college on the edge of a rain forest. This campus-turned-prison (a pattern across the history of World War II prisons) already had an infirmary, but it was in disrepair. Moreover, the Navy nurses and their colleagues lacked equipment and many of the necessary furnishings. They therefore enlisted the help of other internees, especially those with experience in manufacturing and construction, who were able to help fit out a 25-bed establishment and craft many of the requisite equipment from found materials. Corrugated sheets constituted the raw material for emesis basins; old cans in modified form became bedpans.[37]

There were further innovations—too many to enumerate, even. Some were intuitive, like the fabric scraps the Navy nurses fashioned into bandages. Other accommodations were improbable yet ingenious: The Navy nurses distilled myriad medicines from the herbs, flowers, and roots growing on the grounds of the camp, even concocting an effective cough suppressant (tuberculosis was rife) out of a solution made primarily out of liquified onions and fruit sugars. Equally impressive, the Navy nurses transformed some of the camp’s untrained inmates into a crack team of hospital orderlies to assist with the expanding needs of a prison population on the slow, inexorable slide into acute malnutrition and, soon enough, starvation.[38]

The worsening conditions from 1943 to 1944 ultimately outmatched Los Baños’s internee government. As the daily ration supplied by the Japanese began to dwindle, the vegetable gardens that provided internees with supplemental calories proved insufficient as primary sources of nourishment. In 1944, the people of Los Baños began to starve. Their energies sapped, they were scarcely able to maintain the systems that staved off disease—the makeshift water and sanitation systems, especially. The declining health of the population put further strains on the 11 Navy nurses and their colleagues, themselves trying to work while starving.

Conditions in the camps depended on several factors and developments external to the camps themselves—factors and developments unknown to the inmates, who had no access to news of the outside world, where people could see as early as 1943 that the United States was winning the war in the Pacific. Relentless attacks on Japanese shipping threatened to starve the Home Islands and the rest of the empire, including prisoners of war and civilian internees, of food, fuel, and other supplies. The fortunes of the Navy nurses, their colleagues, and the others at Los Baños were therefore tied to the fortunes of the Japanese Empire, now in its death throes.

As a function of the emergency, Japanese policies and practices regarding prisoners became crueler.[39] At the end of 1943, a new decree notified U.S. civilians still uncaptured—in hiding, all of them—in the Philippines that they were now sentenced to death: “After January 25, 1944, any American found on the Islands, whether unsurrendered soldier or civilian, will be summarily executed.”[40] In response, General MacArthur, from his headquarters in Australia, stepped up efforts to rescue Americans and Allied nationals by submarine. Hundreds made it to safety in this way, but such rescue was unavailable to Americans and Allied nationals like the 11 Navy nurses at Los Baños, already in Japanese custody.[41]

In keeping with the radicalization of Japanese policy toward enemy nationals, the Japanese army assumed control of civilian camps across the empire in early 1944, a shift that blurred the distinction between prisoners of war (military personnel) and internees (civilians, including the 11 Navy nurses and everyone at Los Baños, according to Japanese classifications).[42]

Finally, in late 1944, the Japanese supply system collapsed, with so many of its requisitioned merchant vessels succumbing to Allied attacks at sea, and this collapse reduced rations at Los Baños to 500 grams of low-grade rice a day by 1945.[43] Nevertheless, right up to their rescue in late February 1945, the 11 Navy nurses and their colleagues continued to treat the sick and dying.

What explains this perseverance? In a study on women’s responses to occupation, historian Theresa Kaminski finds that throughout the region, women used work and activity more generally to keep themselves and others alive, to distract from the terror and pain, to alleviate the burdens of others, and to claim the shreds of authority that a person needs in order still to feel like a person.[44]

Rescue—23 February 1945

Rescue came out of the blue around 7:00 a.m. on 23 February 1945, when U.S. Army paratroopers descended on the Los Baños Internment Camp, still deep behind enemy lines.[45] U.S. Army Soldiers and Allied guerrillas meanwhile erected a road block, and a U.S. Army infantry battalion pushed into the camp.[46] They found the guards engaged in their regular morning calisthenics and managed to kill nearly all of them, probably more than 200 men. The surviving Japanese personnel fled the scene.

From her vantage in the hospital, Margaret Nash could hear the gunfire and explosions. She could see that the barracks were ablaze, too, yet neither she nor any of the other Navy nurses realized that the fires and the terrific noise were the opening stages of a rescue operation.[47] Instead of preparing to leave, then, Nash and her colleagues went about protecting the patients by moving them under the beds. It was only when Nash saw a U.S. Army paratrooper hit the ground that she realized what might be happening. Running to him as he landed, she posed the question most important to any inmate at Los Baños this late in the war: “Do you have any food?”[48]

Still, the nurses stayed at their posts, attending patients and even treating one of the rescuers, a wounded U.S. Army paratrooper, until it was time to evacuate the camp.[49] Japanese reinforcements might arrive at any moment and add to the bloodbath. Nash and the others therefore joined their patients in the tractors that took them all down to the shore, where 54 amtracs were waiting to spirit the Soldiers, Navy nurses, and internees to safety.[50]

Nash and her colleague, Edwina Todd, were carrying the camp’s youngest evacuees, two baby girls, one of them—Elizabeth, Nash’s infant charge—only three days old. On the bumpy ride to the beach, Nash and Todd held on to the babies while the other Navy nurses and their colleagues continued to care for the sick and injured.

Once on the beach, however, the situation spun out of control. Japanese gunners opened fire from afar, and Nash and her colleagues scrambled to save their charges. After a terrifying period in which Nash shielded the baby Elizabeth from the bullets flying just overhead, Nash and the others made it to one of the amtracs.

But the moment of departure brought a further touch of horror: Confusion on board Nash’s amtrac resulted in the vessel setting off before the doors were closed, which caused water to rush in. “We held the babies over our heads,” Nash remembers, “wondering after all this if we were going to drown.”[51] Someone got the doors closed just in time and, within an hour or so, which must have seemed interminable, the amtracs had outrun the Japanese gunfire and were approaching safer shores.

Once at the U.S. Army encampment—at the former Bilibid prison, of all places—Nash rushed baby Elizabeth to a doctor. He told her that the baby, likely suffering from more than one infection, would need penicillin. “What’s that,” Nash asked. In prison, she had missed the sensational news of this new miracle drug.[52]

Next, Nash swallowed a bit of lunch—her first meal in months—and then, as if she and the other Navy nurses had not just escaped from years of brutalization, Nash joined her colleagues for a 10-day stint tending to wounded Soldiers as they were felled by the ongoing Battle of the Philippines, which still raged in dangerous proximity.

Return to the United States—10 March 1945

The Navy nurses arrived by plane in San Francisco on 10 March 1945. Well-wishers welcomed them with a banquet. It seemed to Nash as if the tables held “all the food in the world, but we couldn’t eat it,” she explains; “Everything I ate, I would throw up.”[53]

It took Nash years to recover her health, in fact. Several decades later, in recounting her story, Nash presents the effects of her internment and rescue with a sense of ambivalence that reveals the unseen toll internment could take on young women in particular, forced as they were to suspend their lives and then resume them again in peacetime as if nothing extraordinary had happened:

[At San Francisco, upon arrival,] we were given physical examinations, and I had it all. I was still swollen from the beriberi, and they discovered I had tuberculosis. I can remember someone saying that I didn’t have long to live, as though I couldn’t hear. I went across the country to recuperate at St. Albans, New York.

Uncle Murray was still in congress, and my mother wouldn’t let him near the house because she held him responsible for the whole thing.

A sad postscript to this is, because of my poor health, which lasted several years, I never tried to get in touch with my fiancé. We never knew if the other was alive.

A nice postscript to the whole story is that baby Elizabeth grew up to be a medical doctor, married, and had two children. She has kept in touch all these years and recently contacted me to see if she could get a birth record. She had nothing.

I know what helped me through that ordeal: my religion, my family, my profession, and my sense of humor.[54]

Margaret Nash, the ten other Navy nurses, and their three civilian nursing colleagues received Bronze Star Medals from the Army for their three years’ work as medical practitioners behind the prison walls.

–––Adam Bisno, Ph.D., NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, February 2020

****

[1] Quoted in Diane Burke Fessler, No Time for Fear: Voices of American Military Nurses in World War II (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1996), 99.

[2] Elizabeth M. Norman, We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan by the Japanese (New York: Random House, 1999), 13.

[3] Quoted in Fessler, No Time for Fear, 100.

[4] Norman, We Band of Angels, 5.

[5] Evelyn M. Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee, All This Hell: U.S. Nurses Imprisoned by the Japanese (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2000), 1.

[6] Quoted in Fessler, No Time for Fear, 79.

[7] For the implications of this dynamic on the fate of the Philippines, see H. W. Burns, Bound to Empire: The United States and the Philippines (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 185.

[8] Burns, Bound to Empire, 188.

[9] Monahan and Neidel-Greenlee, All This Hell, 11.

[10] Burns, Bound to Empire, 188.

[11] Ibid., 188–89.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Norman, We Band of Angels, 16–17.

[14] Bureau of Naval Personnel, Information Bulletin, No. 336 (March 1945), 58.

[15] Fessler, No Time for Fear, 80; Norman, We Band of Angels, 16.

[16] Burns, Bound to Empire, 188.

[17] Burns, Bound to Empire, 195 and 203.

[18] See Fessler, No Time for Fear, 86.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Quoted in Burns, Bound to Empire, 199.

[21] Quoted in Fessler, No Time for Fear, 87.

[22] Quoted in Burns, Bound to Empire, 199.

[23] Fessler, No Time for Fear, 87.

[24] See Mary Ellen Condon-Rall and Albert E. Cowdrey, The Medical Department: Medical Service in the War Against Japan (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1998), 374–75.

[25] Norman, We Band of Angels, 145.

[26] Ibid., 171.

[27] Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Department, 376.

[28] Norman, We Band of Angels, 143.

[29] Ibid., 145–46. Other instances of prisoner government include those at U.S. internment camps for Americans of Japanese descent and the Theresienstadt Ghetto for European Jews, a concentration camp in the present-day Czech Republic. On the gender-historical dimensions of internee government at Japanese camps in and around the Philippines during World War II, see Theresa Kaminski, Prisoners in Paradise: American Women in the Wartime South Pacific (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 237.

[30] Norman, We Band of Angels, 157.

[31] Ibid., 146.

[32] Kaminsky, Prisoners in Paradise, 238.

[33] Norman, We Band of Angels, 167.

[34] Ibid., 171.

[35] Ibid., 171–72.

[36] Ibid., 172–73.

[37] Ibid., 174; Bureau of Naval Personnel, Information Bulletin (op. cit.), 58.

[38] Norman, We Band of Angels, 175–76; Bureau of Naval Personnel, Information Bulletin (op. cit.), 58.

[39] The same was true of Nazi Germany. On the theory of radicalization borne of emergency in the context of impending defeat, see Robert O. Paxton, “The Five Stages of Fascism,” Journal of Modern History 70 (1998), 1–23.

[40] Quoted in Larry S. Schmidt, “American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao during the Japanese Occupation, Master’s Thesis, Command and General Staff College (1982), 38.

[41] Ibid., 38–39; Michael Sturma, Freemantle’s Submarines: How Allied Submarines and Western Australians Helped to Win the War in the Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 133; U.S. Department of the Navy, “Submarine Activities Connected with Guerilla Organizations, Prepared by the Intelligence Center, United States Seventh Fleet,” Type Commands 1945, World War II Command File, Record Group 38, Modern Military Records Branch, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

[42] Norman, We Band of Angels, 183–84; Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Department, 376–77.

[43] Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, 374–75; Norman, We Band of Angels, 212.

[44] Kaminski, Prisoners in Paradise, 240.

[45] Bureau of Naval Personnel, Information Bulletin (op. cit.), 58.

[46] Norman, We Band of Angels, 212.

[47] Ibid.; Fessler, No Time for Fear, 99 and 102.

[48] Fessler, No Time for Fear, 99.

[49] Ibid., 102.

[50] Norman, We Band of Angels, 212.

[51] Quoted in Fessler, No Time for Fear, 100.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid., 101–102.

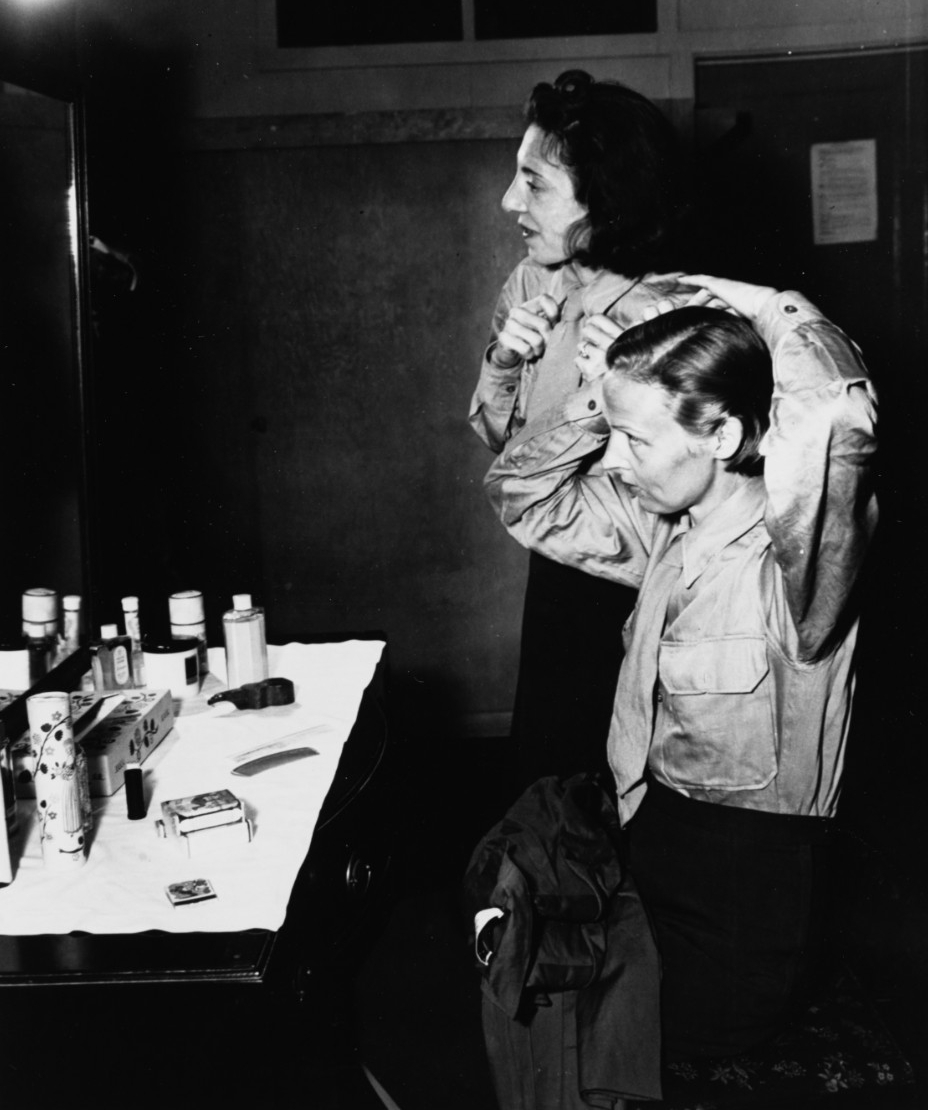

Dressed in new Navy nurse uniforms, in the nurses quarters at Aiea Naval Hospital, Honolulu, Hawaii, early March 1945. Seated, left to right: Mary Nelson (née Harrington), Eldene Paige, Laura M. Cobb, Margaret Nash, Edwina Todd, and Bertha Evans. Standing, left to right: Mary Chapman, Goldie O’Haver, Dorothy Still, Susie Pitcher, and Helen Gorzelanski. (NH 94953)

The 11 Navy nurses freed from internment in the Philippines, upon their arrival in Honolulu, early March 1945. Left to right: Edwina Todd, Margaret Nash, Maureen Davis, Dorothy Still, Goldie O’Haver, Laura M. Cobb, Mary Nelson (née Harrington), and Mary Chapman. They are wearing Army nurse uniforms. (NH 94951)